A. As you read the Teach for America case, one issue that comes up is that Wendy Kopp seem to have a personal barrier to effective communication. Looking at the list of personal barriers, what is one barrier that seems to exist in this case. What is the barrier and why do you say it applies to Wendy Kopp and this case? Explain your answer using supports from the chapter and the case.

B. Using supports from the chapter, what can be done to improve communications? Explain your answer.

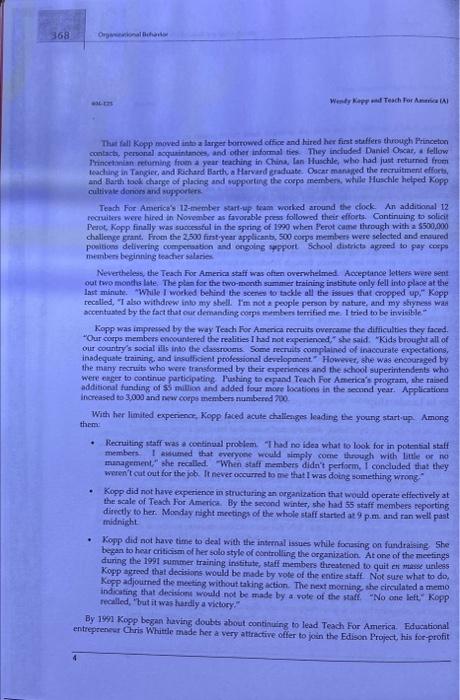

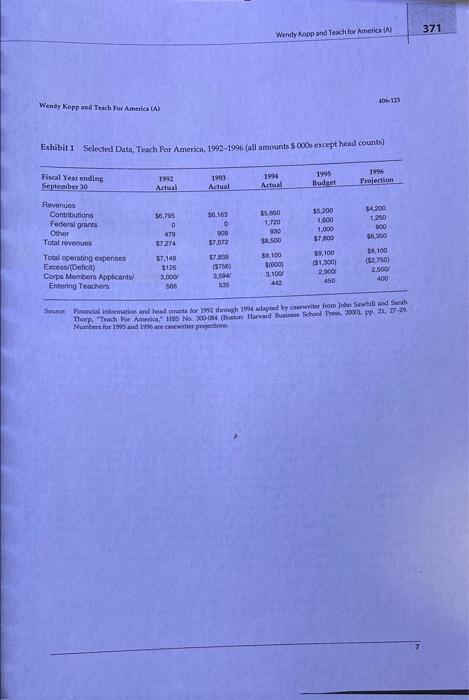

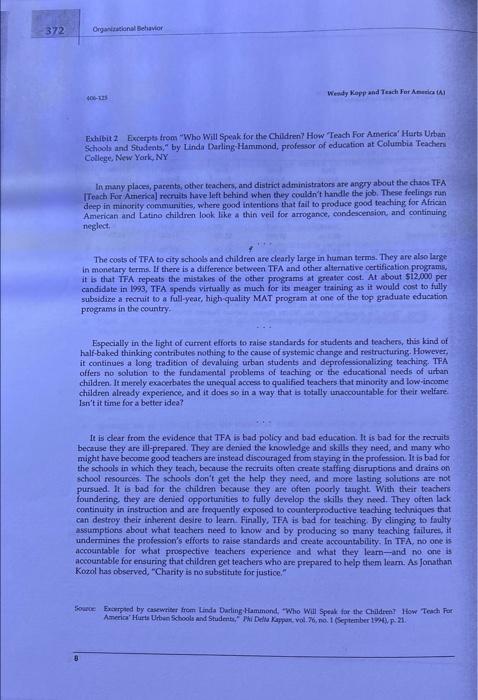

365 Wendy and teach for America HARVARD BUSINESS SCHOOL 9-406-125 HILLEORGE DEANA MATEN ANDREWNIAN Wendy Kopp and Teach For America (A) It is exhausting to have trur passion, but it is hard to mmaginer anything more fulfilling - Wendy Kopp, President and Founder of Teach For America The normally upbeat Wendy Kopp, founder of Teach For America, was feeling discouraged as she had dinner in early 1995 with a former colleague who had left for Harvard Business School. After working 100 hours a week for five years to build Teach For America from nothing to a yearly intake of 500 wachers, Kopp felt overwhelmed by the financial pressures of raising money to keep the organization going Just as she was expanding Teach For America and creating two additional organizations, TEACHI and The Learning Project, Kopp found that many of the initial funders had decided not to continue funding. As a consequence, the organization's deficits were growing rapidly. Internal premium caused by shortfalls in teacher recruiting shortage of management talent and undeveloped management systems were also contributing to the crisis. With a cumulative deficit of $1.2 million and an additional shortfall of $1.3 million projected in the current year, the organization's future was in question. (See Exhibit 1 for a summary of Teach For America's financial statement) The crisis had intensified since a critical article written by Linda Darling Hammond appeared in the September 1994 issue of Phu Dil Kapper, an infupitial educators oumal. At first Kopp med that the article's blistening critique of Teach For America and her leadership w over the top that no one would take it seriously. Much to her chagrin, she found the article led to continuing questions from funders and ongoing challenges from the media. (See Exhibit 2 for excerpts from the artide) Throughout her 27 years, Kopp had died on tenacity and hard work to get through difficult times. She wondered whether the organization she had built could survive this is the constant pressure was taking its toll on her and her stall. She described a knot of tension forming in my chest and reflected in the preceding months Thad slept as little and worked as hard as Thed ever in my life. I tried to maximize every minute of every workday. If we could not meet our payroll. which was a very real possibility, people wouldn't be able to pay their rent or have money for meals I couldn't let this happen. Fear that we might let them down kept me going." Kopp recognised the financial pressures were so severe that she had no option but to step back and re-camine the organization's future. Absolutely deflated, she suggested to her former colleague that maybe she should dose down Teach For America. An hour later, she left the restaurant The Diare Mape MAIMIX AN Mdeepened the cow. The me GARIAN all pronary data thawaf effective map Cyrildent and folla depender mit waardig oo, MAwwww No part of my be producent worden online from mania yg ingerichte School 366 Orative Wendy Teacher determined to gather her management team together the next day to address a basic question Should we continue Early Years Wendy Kopp grew up in the privileged Park Cities neighborhood of Dallas "The community is which I grew up was extraordinarily folated from reality and disparities in education and opportunity," she observed More than 95% of Highland Park High School students de college. From modest beginnings. Kepp's parents worked tremendously hard to provide for the family. They grew up in aallowa and Minnesota and supported themselves through college with scholarships and part-time jobs. Seeking a warmer climate, they settled in Dallas and tumedas newsletter into a local interest magarine targeted at convention goes there and in other Teresa Kopp was born in 1967, and her brother in 1969 Developing Drive Despite the educational advantages available to her, kopp recalled her early education as a personal struggle. A self-described shy and awkward kid." she found herself behind her damas when she transferred from a parochial school to the public school system in the secth grade. She out to improve her performance through reledes hard work. "I was obsessive. I did not feel likel was as smart as a lot of others, but I had a mindset that I would just etwork everyone elsesbe explained. Kopp worked on her own in this single minded pursuit Kopp and her brother also worked in her parents' small publishing business, "I did the most mundane things on the planet" she said. "My was to move the magazines from the printers boxes and there were a lot of them-into bones for distribution. From an early age, she planned to find her own path outside of Dallas rather than following her parents career. Kopp realized that educational achievement could be a springboard to the world beyond. A freshman, she ranked tenth of 400 students. Over the next three years, she became editor of the school newspaper, joined the drama and debate dubs, and graduated valedictorian of here with no pushing from her parents, Kopp applied to and was accepted by Princeton University. Once at Princeton, she studied at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and Interational Affairs Kopp led the Finding Direction Kopp's extracurricular activities at Princeton were even more time consuming than her formal studies. She joined the staff of the Foundation for Student Communication (PSC), a student-managed Initiative that published magazines and conducted leadership conferences organization in her junior and senior years, managing a staff of 60 student volunteers and raising over $1 million annually from advertisements and contribution. When I took PSC over, it wa going through near death experiences. Kopp explained. "We built it as a team, taciding us from figuring out how to grow it financially to how to attract more talented college students Uncertain about her career path, Kopp knew she wanted to make an impact "Having worked 70 hours a week on top of the full Princeton academic load to get FSC where it was, I thought, I am going to work this hard after college, I want to make sure it makes a difference. Kepp was reluctant to follow her peers into two year corporate training programs after graduation in part because she felt she had already seen that life through her extracurricular experiences. She wanted to pursue 2 367 Wendy Kopp and Teach for America AS 106-135 Wendy Koppand Teach For America more fulllling work, and believed there were thousands of graduating vendors who shared her desire to find work that would make a social impact Thad ee (that there were thousands of people who were searching for a way that would be maken val diference in the world." she said In the fall of her senior year, Kopp and her PSC colleagues organized a national conference on education reform. During a discussion about teacher quality, che speaker noted a lack of education majors to teach in the nation's lowest income communities Suddenly, an idea came to be "Can we have a national teacher corps modeled at the Peace Corpor" As her senior year progremed. Kopp continued to develop her idea, imagining the elect het program would have on both students and young leaders Meanwhile, she was frustrated in her own joe search as her efforts netted five rejections and no offers. She was too late to prepare for licensure through Princeton's teacher preparation program, and discovered that the career wervices office could not answether basic questions about preparation for teaching A New York City school reciter old her that her best prospect for being hired was to wait until Labor Day and hope for a last-minule opening. In need of income, Kopp knew this option was not feasible As she developed her plan for a teacher corps she reasoned that her organisation could recruit as aggressively on campuses as the corporate caters Deciding to write her senior thesis on her plan, she crafted a proposal to recruit a cops of college graduates as novice teachers in five or sex urbano rural areas at the cost in the first year of $2.5 millionShe sent a better to President George H. W. Bush proposing a national teacher corps on the model of the Peace Corps, only to receive a form letter informing her that her job application had beended Stepping Up to Leadership "The idea was to create a movement of some of our nation's most promising future leaders to ameliorate inequities in education by starting with a critical mass of at least 500 corps members." Kopp explained. She turned to educators and advisers, who tried to dissuade her from her plan. Her thesis advisor asked her. "Do you know how hard it is to raise twenty-five hundred dollars, much less $2.5 million?" Kopp felt confident that she could get support from H. Ross Perot, founder of EDS. "Having grown up in Dallas when Perot caged to improve Texas schools, I was certain be would love my idea and appreciate something so mntrepreneurial. After turning in her thesis, she rewrote it as a proposal and sent it to Perot and 30 CEOs of companies interested in education reform. A week later she followed up with phone calls She got no response at all from l'erot, but landed meetings with several lower level cxecutives at target companies. She recalled wondering why the CEOs did not think this idea was worthy of their time. A month before her graduation, Kopp had secured donated office space in Manhattan from Union Carbide and a $26.000 grant from MOL Working long hours alone in her browed midtown New York City office, Kopp found her freedom and independence exhilarating She spent the summer making contacts in philanthropy and education reform, sharing her plan and assembling a board of advisors. She discovered that most activists and funders were convinced that teacher training and recruitment were best left to such traditional channels as university-based degree programs and district hiring processes. However, Kopp encountered enthusiastic response from several school districts. One superintendent exclaimed. "If you can get students from those schools to teach here, I'll hire all five hundred 368 Opera Wendy Mary Teach For Al That fall kopp moved into a larger borrowed office and hired her first staffers through Princeton contact personal noquinon, and other informal ties. They included Daniel Oscar, fellow Irince reming from a year teaching in China, Lan Huschde, who had just returned from teadung in Tangler, and Richard Bartha Harvard graduate. Oscar managed the recruitment efforts, and Barth took charge of placing and supporting the corps members, while Huschle helped Kopp cultivate donors and supporters Teach For America' 12-member start-up team worked around the clock. An additional 12 recruiters were hired in November as favorable press followed their efforts. Continuing to solicit Perot Ropp finally was successful in the spring of 1990 when Perot came through with a $500,000 challenge grant. From the 2.500 first year applicants, 500 corps members were selected and ensured positions delivering compensation and ongoing support School districts agreed to pay cops men beginning teacher salaries Nevertheless, the Teach For American staff was often overwhelmed Acceptance letters were sent out two months late. The plan for the two-month summer training institute only fell into place at the last minute. While I worked behind the scenes to take all the issues that cropped up." Kopp recalled, "I also withdrew into my shell. I'm not people person by nature, and my shyness was accentuated by the fact that our demanding corps tombers terrified me. I tried to be invisible Kopp was impressed by the way Teach For America recruits overcame the difficulties they faced, Our corps members encountered the realities I had not experienced," she said. "Kids brought all of our country's social alls into the dassrooms Some recruits complained of inaccurate expectations, inadequate training, and insuficient professional development. However, she was encouraged by the many recruits who were transformed by their experiences and the school superintendents who were eager to continue participating Pushing to expand Teach For America's program, she raised additional funding of million and added four more locations in the second year. Applications increased to 3,000 and new corps members numbered 700 With her limited experience, Kopp faced acute challenges leading the young start-up Among them Recruiting staff was a continual problem "Thad no idea what to look for in potential staff members med that weryone would simply come through with little or no management," she recalled. When staff members didn't perform, concluded that they weren't cut out for the job. It never occurred to me that I was doing something wrong Kopp did not have experience in structuring an organization that would operate effectively at the scale of Teach For America. By the second winter, she had 55 staff members reporting directly to her. Monday night meetings of the whole staff started at 9pm and ran well past midnight Kopp did not have time to deal with the internal issues while focusing on fundraising She began to hear criticism of her solo style of controlling the organization. At one of the meetings during the 1991 summer training institute, staff members threatened to quit en masse unless Kopp agreed that decisions would be made by vote of the entire staff. Not sure what to do, Kopp adjourned the meeting without taking action. The next morning, she circulated a memo indicating that decisione would not be made by a vote of the stall "No one left. Kopp recalled, "but it was hardly a victory By 1991 Kopp began having doubts about continuing to lead Teach For America. Educational entrepreneur Chris Whittle made her a very attractive offer to join the Edison Project his for-profit . 369 Wendy Kapp and Teach for America US Wendy Kapp and Teacher America (A) Initiative that initially set out to design a new kind of school system. She was reluctant to leave Teach For America in the midst of its growing pains and without a successor in sight to facilitate her move. Whittle referred her to Nick Glover, an organizational development expert who was experienced in working with entrepreneurial organizations Glover worked on helping the organization develop the management and decision-making structures necessary to operate more effectively Glover's services had an unintended effect on Kopp. Once I saw that the problems could be solved," she said. "I didn't want to leave any more. I felt there was a higher level to achieve at Teach For America Expanding Teach For America's Reach With a renewed sense of possibility. Teach For America launched new initiatives long envisioned by Kopp and her team with the help of funders interested in supporting systemic solutions to raise teacher quality. Kopp launched a new unit, TEACHI, which was intended to provide recruiting services on a contract basis to any school district. A second new initiative called The Learning Project grew out of frustration with the current assumptions and regulations that governed the design of schools Innovative, groundbreaking summer programs that delivered results would become the models for new school programs. To broaden her management team, Kopp named Dan Porter president of Teach For America, Barth president of TEACHI, and Oscar president of The Learning Project, as she continued as president of Teach For America, Inc Just as the new ventures were poised to launch, Teach For America's funding base began to contract. In 1994 Teach For America's start-up funders put the organization on notice that their three year start-up grants were not intended to be sustaining, so Teach For America had to find new sources of support. Major foundations devoted to education were pursuing newer change models as other teacher training enterprises were pursuing the same philanthropic support. kopp supported The Learning Project out of Teach For America's general budget. TEACHI pursued independent start-up funding and planned to move to a revenue generating footing in its second or third year Kopp continued to be preoccupied with Teach For America's ongoing funding crisis, devoting almost all her time to raising the minimum funds. "All my time went into finding the $200,000 needed to make payroll every two weeks." she recalled. Meanwhile, the organization's debt continued to mount, as it was still unable to pay UCLA the $600,000 it owed for its 1993 summer institute, and fiscal year 1994 resulted in another $600,000 shortfall Many of Teach For America's major philanthropic supporters voiced concerns about Teach For America's financial instability and its ability to fund its basic needs. They encouraged Kopp to name an experienced chief operating officer or business manager, and a full-time director of development, while scaling TEACHI back to a pilot program Kopp turned to key funders to advance bridge financing to Teach For America or accelerate existing grants to head off insolvency. With the passage of President Clinton's national service legislation, an accelerated $2 million grant from the National Corporation for Public Service enabled Teach For America to hold its 1994 summer institute At the same time, education experts like Darling Hammond began to mount antiques of Teach For America Kopp recalled her first reaction to Darling Hammond's article portraying Teach For America as an organization that worked for its own interest against the interest of helpless communities. It felt like a punch in the chest. I read it more as a personal attack than as an academic analysis of our efforts," she recalled. 370 Orational Bendor Wendy Kapp and Teach For America (A) The Challenge Given the enormity of the problems in public education, Kopp felt a moral imperative to continue Teach For America, but she had a growing uncertainty about whether her team could withstand the Current financial pressures Shortly before going to dinner, Kopp had reviewed once again, Teach For America's financial projections for 1995 and 1996. Even with level expenses and no salary increases, the projections indicated deficits mounting from $13 million in the current year to $2.5 million by 1976 as forecasted contributions declined She sho worried about whether she could count on the continuation of the grant from the National Corporation for Public Service If Teach For America was going to survive. Nepp knew it had to become financially stable. This required painful action to prioritize its activities Could she restructure Teach For America to bring it into line with the fiscal realities, or should she decide to shut it down? If she chose restructuring should the cuts in operating expenses be targeted at the number of teachers, their professional development, staff overhead of Teach For America, expanded training Institute, or new start-ups? As she pondered her options, she had a number of insights Cutting the size of the teacher corps would eliminate direct costs, but the impact would be limited due to remaining fixed costs The 60 experienced teachers hired to provide ongoing professional development added valuable expertise to the organization, but were quite costly and evidence was lacking that their work actually increased the effectiveness of satisfaction of the teacher corps While staff cuts might bring the budget into line, it would also disrupt the young care of Teach For America staft, diminate support for recruits, and crimp the flow of teacher applications . . Spinning off or shutting down the initiatives would create orphan programs that might eliminate her key senior leaders and disappoint many funders and staff members who had invested in them. That would mark the passage of two generations of Teach For America leaders, and any plan would have to be implemented by a new team Whule Kopp was convinced that Teach For America was positively impacting the quality of education students received, funders and experts were challenging Teach For America to document its claims about students' higher achievement levels Kopp's vision and creative ideas had created and launched Teach For America, but now she had to decide whether or not the organization could survive in the future. Did she have tl skills and the continuing energy to lead it through this crisis? 371 Wendy Kapp and Teach for America 406-125 Wendy Kopp and Teach For America (A) Exhibit 1 Selected Data, Teach For America, 1992-1996 (all amounts 5000s except head counts) Fiscal Year ending September 30 1992 Actual 1993 Actual 191 Actual 1995 Hadeet 1995 Projection Revenues Contributions Federal grants Other Total revenues Total operating expenses Excess/(Deficity Corps Members Applicants Entering Teachers 54.200 1.250 000 56.350 56,795 0 479 57.274 37,148 5128 $6,160 O 900 57.072 15,150 1.720 930 $8.500 $5,200 1,800 1.000 7.100 $0,100 151,300 2,000 450 ST 838 576 2,50 35 39.100 S1000 3.100 $9,100 12.750) 2.500 400 506 Source and deeration and head come for through 19 adapted by carwriter from John Sawhill and Sarah Tharp "Teach For American Hes No 300 Oto Harvard New School Pr. 200L pp 21, 20-9. Number for 1995 and 1956 rewrier projections 372 Organizational Behavior Wendy Kopp and Teach Fort 106 Exhibit 2 Excerpts from "Who Will Speak for the Children? How Teach For America' Hurts Urban Schools and Students," by Linda Darling Hammond, professor of education at Columbia Teachers College New York, NY In many places, parents, other teachers, and district administrators are angry about the chaos TFA Teach For America) recruits have left behind when they couldn't handle the job. These feelings run deep in minority communities, where good intentions that fail to produce good teaching for African American and Latino children look like thin vell for arrogance, condescension, and continuing neglect The costs of TFA to city schools and children are clearly large in human terms. They are also large in monetary terms. If there is a difference between TFA and other alternative certification programs, it is that TFA repeats the mistakes of the other programs at greater cost. At about $12.000 per candidate in 1993, TFA spends virtually as much for its meager training as it would cost to fully subsidize a recruit to a full-year, high-quality MAT program at one of the top graduate education programs in the country. Especially in the light of current efforts to raise standards for students and teachers, this kind of half-baked thinking contributes nothing to the cause of systemic change and restructuring. However, it continues a long tradition of devaluing urban students and deprofessionalizing teaching TFA offers no solution to the fundamental problems of teaching or the educational needs of urban children. It merely exacerbates the unequal access to qualified teachers that minority and low-income children already experience, and it does so in a way that is totally accountable for their welfare Isn't it time for a better idea? It is clear from the evidence that TFA is bad policy and bad education. It is bad for the recruit because they are ill-prepared. They are denied the knowledge and skills they need, and many who might have become good teachers are instead discouraged from staying in the profession. It is bad for the schools in which they trach, because the recruits often create staffing disruptions and drains on school resources. The schools don't get the help they need, and more lasting solutions are not pursued. It is bad for the children because they are often poorly taught With their teachers foundering they are denied opportunities to fully develop the skills they need. They often lack continuity in instruction and are frequently exposed to counterproductive teaching techniques that can destroy their inherent desire to learn. Finally, TFA is bad for teaching. By clinging to faulty assumptions about what teachers need to know and by producing so many teaching failures, it undermines the profession's efforts to raise standards and create accountability. In TFA, no one is accountable for what prospective teachers experience and what they leam-and no one is accountable for ensuring that children get teachers who are prepared to help them leam. As Jonathan Kozol has observed, "Charity is no substitute for justice." Se Excerpted by Casewriter from Linda Darling Hammond, "Who Will Speak for the Children! How Teach Por America Kurta Urban Stools and Students. Ph Dellapur. vol. 76, no. 1 (September 1944p 21 365 Wendy and teach for America HARVARD BUSINESS SCHOOL 9-406-125 HILLEORGE DEANA MATEN ANDREWNIAN Wendy Kopp and Teach For America (A) It is exhausting to have trur passion, but it is hard to mmaginer anything more fulfilling - Wendy Kopp, President and Founder of Teach For America The normally upbeat Wendy Kopp, founder of Teach For America, was feeling discouraged as she had dinner in early 1995 with a former colleague who had left for Harvard Business School. After working 100 hours a week for five years to build Teach For America from nothing to a yearly intake of 500 wachers, Kopp felt overwhelmed by the financial pressures of raising money to keep the organization going Just as she was expanding Teach For America and creating two additional organizations, TEACHI and The Learning Project, Kopp found that many of the initial funders had decided not to continue funding. As a consequence, the organization's deficits were growing rapidly. Internal premium caused by shortfalls in teacher recruiting shortage of management talent and undeveloped management systems were also contributing to the crisis. With a cumulative deficit of $1.2 million and an additional shortfall of $1.3 million projected in the current year, the organization's future was in question. (See Exhibit 1 for a summary of Teach For America's financial statement) The crisis had intensified since a critical article written by Linda Darling Hammond appeared in the September 1994 issue of Phu Dil Kapper, an infupitial educators oumal. At first Kopp med that the article's blistening critique of Teach For America and her leadership w over the top that no one would take it seriously. Much to her chagrin, she found the article led to continuing questions from funders and ongoing challenges from the media. (See Exhibit 2 for excerpts from the artide) Throughout her 27 years, Kopp had died on tenacity and hard work to get through difficult times. She wondered whether the organization she had built could survive this is the constant pressure was taking its toll on her and her stall. She described a knot of tension forming in my chest and reflected in the preceding months Thad slept as little and worked as hard as Thed ever in my life. I tried to maximize every minute of every workday. If we could not meet our payroll. which was a very real possibility, people wouldn't be able to pay their rent or have money for meals I couldn't let this happen. Fear that we might let them down kept me going." Kopp recognised the financial pressures were so severe that she had no option but to step back and re-camine the organization's future. Absolutely deflated, she suggested to her former colleague that maybe she should dose down Teach For America. An hour later, she left the restaurant The Diare Mape MAIMIX AN Mdeepened the cow. The me GARIAN all pronary data thawaf effective map Cyrildent and folla depender mit waardig oo, MAwwww No part of my be producent worden online from mania yg ingerichte School 366 Orative Wendy Teacher determined to gather her management team together the next day to address a basic question Should we continue Early Years Wendy Kopp grew up in the privileged Park Cities neighborhood of Dallas "The community is which I grew up was extraordinarily folated from reality and disparities in education and opportunity," she observed More than 95% of Highland Park High School students de college. From modest beginnings. Kepp's parents worked tremendously hard to provide for the family. They grew up in aallowa and Minnesota and supported themselves through college with scholarships and part-time jobs. Seeking a warmer climate, they settled in Dallas and tumedas newsletter into a local interest magarine targeted at convention goes there and in other Teresa Kopp was born in 1967, and her brother in 1969 Developing Drive Despite the educational advantages available to her, kopp recalled her early education as a personal struggle. A self-described shy and awkward kid." she found herself behind her damas when she transferred from a parochial school to the public school system in the secth grade. She out to improve her performance through reledes hard work. "I was obsessive. I did not feel likel was as smart as a lot of others, but I had a mindset that I would just etwork everyone elsesbe explained. Kopp worked on her own in this single minded pursuit Kopp and her brother also worked in her parents' small publishing business, "I did the most mundane things on the planet" she said. "My was to move the magazines from the printers boxes and there were a lot of them-into bones for distribution. From an early age, she planned to find her own path outside of Dallas rather than following her parents career. Kopp realized that educational achievement could be a springboard to the world beyond. A freshman, she ranked tenth of 400 students. Over the next three years, she became editor of the school newspaper, joined the drama and debate dubs, and graduated valedictorian of here with no pushing from her parents, Kopp applied to and was accepted by Princeton University. Once at Princeton, she studied at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and Interational Affairs Kopp led the Finding Direction Kopp's extracurricular activities at Princeton were even more time consuming than her formal studies. She joined the staff of the Foundation for Student Communication (PSC), a student-managed Initiative that published magazines and conducted leadership conferences organization in her junior and senior years, managing a staff of 60 student volunteers and raising over $1 million annually from advertisements and contribution. When I took PSC over, it wa going through near death experiences. Kopp explained. "We built it as a team, taciding us from figuring out how to grow it financially to how to attract more talented college students Uncertain about her career path, Kopp knew she wanted to make an impact "Having worked 70 hours a week on top of the full Princeton academic load to get FSC where it was, I thought, I am going to work this hard after college, I want to make sure it makes a difference. Kepp was reluctant to follow her peers into two year corporate training programs after graduation in part because she felt she had already seen that life through her extracurricular experiences. She wanted to pursue 2 367 Wendy Kopp and Teach for America AS 106-135 Wendy Koppand Teach For America more fulllling work, and believed there were thousands of graduating vendors who shared her desire to find work that would make a social impact Thad ee (that there were thousands of people who were searching for a way that would be maken val diference in the world." she said In the fall of her senior year, Kopp and her PSC colleagues organized a national conference on education reform. During a discussion about teacher quality, che speaker noted a lack of education majors to teach in the nation's lowest income communities Suddenly, an idea came to be "Can we have a national teacher corps modeled at the Peace Corpor" As her senior year progremed. Kopp continued to develop her idea, imagining the elect het program would have on both students and young leaders Meanwhile, she was frustrated in her own joe search as her efforts netted five rejections and no offers. She was too late to prepare for licensure through Princeton's teacher preparation program, and discovered that the career wervices office could not answether basic questions about preparation for teaching A New York City school reciter old her that her best prospect for being hired was to wait until Labor Day and hope for a last-minule opening. In need of income, Kopp knew this option was not feasible As she developed her plan for a teacher corps she reasoned that her organisation could recruit as aggressively on campuses as the corporate caters Deciding to write her senior thesis on her plan, she crafted a proposal to recruit a cops of college graduates as novice teachers in five or sex urbano rural areas at the cost in the first year of $2.5 millionShe sent a better to President George H. W. Bush proposing a national teacher corps on the model of the Peace Corps, only to receive a form letter informing her that her job application had beended Stepping Up to Leadership "The idea was to create a movement of some of our nation's most promising future leaders to ameliorate inequities in education by starting with a critical mass of at least 500 corps members." Kopp explained. She turned to educators and advisers, who tried to dissuade her from her plan. Her thesis advisor asked her. "Do you know how hard it is to raise twenty-five hundred dollars, much less $2.5 million?" Kopp felt confident that she could get support from H. Ross Perot, founder of EDS. "Having grown up in Dallas when Perot caged to improve Texas schools, I was certain be would love my idea and appreciate something so mntrepreneurial. After turning in her thesis, she rewrote it as a proposal and sent it to Perot and 30 CEOs of companies interested in education reform. A week later she followed up with phone calls She got no response at all from l'erot, but landed meetings with several lower level cxecutives at target companies. She recalled wondering why the CEOs did not think this idea was worthy of their time. A month before her graduation, Kopp had secured donated office space in Manhattan from Union Carbide and a $26.000 grant from MOL Working long hours alone in her browed midtown New York City office, Kopp found her freedom and independence exhilarating She spent the summer making contacts in philanthropy and education reform, sharing her plan and assembling a board of advisors. She discovered that most activists and funders were convinced that teacher training and recruitment were best left to such traditional channels as university-based degree programs and district hiring processes. However, Kopp encountered enthusiastic response from several school districts. One superintendent exclaimed. "If you can get students from those schools to teach here, I'll hire all five hundred 368 Opera Wendy Mary Teach For Al That fall kopp moved into a larger borrowed office and hired her first staffers through Princeton contact personal noquinon, and other informal ties. They included Daniel Oscar, fellow Irince reming from a year teaching in China, Lan Huschde, who had just returned from teadung in Tangler, and Richard Bartha Harvard graduate. Oscar managed the recruitment efforts, and Barth took charge of placing and supporting the corps members, while Huschle helped Kopp cultivate donors and supporters Teach For America' 12-member start-up team worked around the clock. An additional 12 recruiters were hired in November as favorable press followed their efforts. Continuing to solicit Perot Ropp finally was successful in the spring of 1990 when Perot came through with a $500,000 challenge grant. From the 2.500 first year applicants, 500 corps members were selected and ensured positions delivering compensation and ongoing support School districts agreed to pay cops men beginning teacher salaries Nevertheless, the Teach For American staff was often overwhelmed Acceptance letters were sent out two months late. The plan for the two-month summer training institute only fell into place at the last minute. While I worked behind the scenes to take all the issues that cropped up." Kopp recalled, "I also withdrew into my shell. I'm not people person by nature, and my shyness was accentuated by the fact that our demanding corps tombers terrified me. I tried to be invisible Kopp was impressed by the way Teach For America recruits overcame the difficulties they faced, Our corps members encountered the realities I had not experienced," she said. "Kids brought all of our country's social alls into the dassrooms Some recruits complained of inaccurate expectations, inadequate training, and insuficient professional development. However, she was encouraged by the many recruits who were transformed by their experiences and the school superintendents who were eager to continue participating Pushing to expand Teach For America's program, she raised additional funding of million and added four more locations in the second year. Applications increased to 3,000 and new corps members numbered 700 With her limited experience, Kopp faced acute challenges leading the young start-up Among them Recruiting staff was a continual problem "Thad no idea what to look for in potential staff members med that weryone would simply come through with little or no management," she recalled. When staff members didn't perform, concluded that they weren't cut out for the job. It never occurred to me that I was doing something wrong Kopp did not have experience in structuring an organization that would operate effectively at the scale of Teach For America. By the second winter, she had 55 staff members reporting directly to her. Monday night meetings of the whole staff started at 9pm and ran well past midnight Kopp did not have time to deal with the internal issues while focusing on fundraising She began to hear criticism of her solo style of controlling the organization. At one of the meetings during the 1991 summer training institute, staff members threatened to quit en masse unless Kopp agreed that decisions would be made by vote of the entire staff. Not sure what to do, Kopp adjourned the meeting without taking action. The next morning, she circulated a memo indicating that decisione would not be made by a vote of the stall "No one left. Kopp recalled, "but it was hardly a victory By 1991 Kopp began having doubts about continuing to lead Teach For America. Educational entrepreneur Chris Whittle made her a very attractive offer to join the Edison Project his for-profit . 369 Wendy Kapp and Teach for America US Wendy Kapp and Teacher America (A) Initiative that initially set out to design a new kind of school system. She was reluctant to leave Teach For America in the midst of its growing pains and without a successor in sight to facilitate her move. Whittle referred her to Nick Glover, an organizational development expert who was experienced in working with entrepreneurial organizations Glover worked on helping the organization develop the management and decision-making structures necessary to operate more effectively Glover's services had an unintended effect on Kopp. Once I saw that the problems could be solved," she said. "I didn't want to leave any more. I felt there was a higher level to achieve at Teach For America Expanding Teach For America's Reach With a renewed sense of possibility. Teach For America launched new initiatives long envisioned by Kopp and her team with the help of funders interested in supporting systemic solutions to raise teacher quality. Kopp launched a new unit, TEACHI, which was intended to provide recruiting services on a contract basis to any school district. A second new initiative called The Learning Project grew out of frustration with the current assumptions and regulations that governed the design of schools Innovative, groundbreaking summer programs that delivered results would become the models for new school programs. To broaden her management team, Kopp named Dan Porter president of Teach For America, Barth president of TEACHI, and Oscar president of The Learning Project, as she continued as president of Teach For America, Inc Just as the new ventures were poised to launch, Teach For America's funding base began to contract. In 1994 Teach For America's start-up funders put the organization on notice that their three year start-up grants were not intended to be sustaining, so Teach For America had to find new sources of support. Major foundations devoted to education were pursuing newer change models as other teacher training enterprises were pursuing the same philanthropic support. kopp supported The Learning Project out of Teach For America's general budget. TEACHI pursued independent start-up funding and planned to move to a revenue generating footing in its second or third year Kopp continued to be preoccupied with Teach For America's ongoing funding crisis, devoting almost all her time to raising the minimum funds. "All my time went into finding the $200,000 needed to make payroll every two weeks." she recalled. Meanwhile, the organization's debt continued to mount, as it was still unable to pay UCLA the $600,000 it owed for its 1993 summer institute, and fiscal year 1994 resulted in another $600,000 shortfall Many of Teach For America's major philanthropic supporters voiced concerns about Teach For America's financial instability and its ability to fund its basic needs. They encouraged Kopp to name an experienced chief operating officer or business manager, and a full-time director of development, while scaling TEACHI back to a pilot program Kopp turned to key funders to advance bridge financing to Teach For America or accelerate existing grants to head off insolvency. With the passage of President Clinton's national service legislation, an accelerated $2 million grant from the National Corporation for Public Service enabled Teach For America to hold its 1994 summer institute At the same time, education experts like Darling Hammond began to mount antiques of Teach For America Kopp recalled her first reaction to Darling Hammond's article portraying Teach For America as an organization that worked for its own interest against the interest of helpless communities. It felt like a punch in the chest. I read it more as a personal attack than as an academic analysis of our efforts," she recalled. 370 Orational Bendor Wendy Kapp and Teach For America (A) The Challenge Given the enormity of the problems in public education, Kopp felt a moral imperative to continue Teach For America, but she had a growing uncertainty about whether her team could withstand the Current financial pressures Shortly before going to dinner, Kopp had reviewed once again, Teach For America's financial projections for 1995 and 1996. Even with level expenses and no salary increases, the projections indicated deficits mounting from $13 million in the current year to $2.5 million by 1976 as forecasted contributions declined She sho worried about whether she could count on the continuation of the grant from the National Corporation for Public Service If Teach For America was going to survive. Nepp knew it had to become financially stable. This required painful action to prioritize its activities Could she restructure Teach For America to bring it into line with the fiscal realities, or should she decide to shut it down? If she chose restructuring should the cuts in operating expenses be targeted at the number of teachers, their professional development, staff overhead of Teach For America, expanded training Institute, or new start-ups? As she pondered her options, she had a number of insights Cutting the size of the teacher corps would eliminate direct costs, but the impact would be limited due to remaining fixed costs The 60 experienced teachers hired to provide ongoing professional development added valuable expertise to the organization, but were quite costly and evidence was lacking that their work actually increased the effectiveness of satisfaction of the teacher corps While staff cuts might bring the budget into line, it would also disrupt the young care of Teach For America staft, diminate support for recruits, and crimp the flow of teacher applications . . Spinning off or shutting down the initiatives would create orphan programs that might eliminate her key senior leaders and disappoint many funders and staff members who had invested in them. That would mark the passage of two generations of Teach For America leaders, and any plan would have to be implemented by a new team Whule Kopp was convinced that Teach For America was positively impacting the quality of education students received, funders and experts were challenging Teach For America to document its claims about students' higher achievement levels Kopp's vision and creative ideas had created and launched Teach For America, but now she had to decide whether or not the organization could survive in the future. Did she have tl skills and the continuing energy to lead it through this crisis? 371 Wendy Kapp and Teach for America 406-125 Wendy Kopp and Teach For America (A) Exhibit 1 Selected Data, Teach For America, 1992-1996 (all amounts 5000s except head counts) Fiscal Year ending September 30 1992 Actual 1993 Actual 191 Actual 1995 Hadeet 1995 Projection Revenues Contributions Federal grants Other Total revenues Total operating expenses Excess/(Deficity Corps Members Applicants Entering Teachers 54.200 1.250 000 56.350 56,795 0 479 57.274 37,148 5128 $6,160 O 900 57.072 15,150 1.720 930 $8.500 $5,200 1,800 1.000 7.100 $0,100 151,300 2,000 450 ST 838 576 2,50 35 39.100 S1000 3.100 $9,100 12.750) 2.500 400 506 Source and deeration and head come for through 19 adapted by carwriter from John Sawhill and Sarah Tharp "Teach For American Hes No 300 Oto Harvard New School Pr. 200L pp 21, 20-9. Number for 1995 and 1956 rewrier projections 372 Organizational Behavior Wendy Kopp and Teach Fort 106 Exhibit 2 Excerpts from "Who Will Speak for the Children? How Teach For America' Hurts Urban Schools and Students," by Linda Darling Hammond, professor of education at Columbia Teachers College New York, NY In many places, parents, other teachers, and district administrators are angry about the chaos TFA Teach For America) recruits have left behind when they couldn't handle the job. These feelings run deep in minority communities, where good intentions that fail to produce good teaching for African American and Latino children look like thin vell for arrogance, condescension, and continuing neglect The costs of TFA to city schools and children are clearly large in human terms. They are also large in monetary terms. If there is a difference between TFA and other alternative certification programs, it is that TFA repeats the mistakes of the other programs at greater cost. At about $12.000 per candidate in 1993, TFA spends virtually as much for its meager training as it would cost to fully subsidize a recruit to a full-year, high-quality MAT program at one of the top graduate education programs in the country. Especially in the light of current efforts to raise standards for students and teachers, this kind of half-baked thinking contributes nothing to the cause of systemic change and restructuring. However, it continues a long tradition of devaluing urban students and deprofessionalizing teaching TFA offers no solution to the fundamental problems of teaching or the educational needs of urban children. It merely exacerbates the unequal access to qualified teachers that minority and low-income children already experience, and it does so in a way that is totally accountable for their welfare Isn't it time for a better idea? It is clear from the evidence that TFA is bad policy and bad education. It is bad for the recruit because they are ill-prepared. They are denied the knowledge and skills they need, and many who might have become good teachers are instead discouraged from staying in the profession. It is bad for the schools in which they trach, because the recruits often create staffing disruptions and drains on school resources. The schools don't get the help they need, and more lasting solutions are not pursued. It is bad for the children because they are often poorly taught With their teachers foundering they are denied opportunities to fully develop the skills they need. They often lack continuity in instruction and are frequently exposed to counterproductive teaching techniques that can destroy their inherent desire to learn. Finally, TFA is bad for teaching. By clinging to faulty assumptions about what teachers need to know and by producing so many teaching failures, it undermines the profession's efforts to raise standards and create accountability. In TFA, no one is accountable for what prospective teachers experience and what they leam-and no one is accountable for ensuring that children get teachers who are prepared to help them leam. As Jonathan Kozol has observed, "Charity is no substitute for justice." Se Excerpted by Casewriter from Linda Darling Hammond, "Who Will Speak for the Children! How Teach Por America Kurta Urban Stools and Students. Ph Dellapur. vol. 76, no. 1 (September 1944p 21