Question: A PDF version of this assignment is attached.I'll also put it in the Assignments folder in Files.As usual, you'll answer the questions in the online

A PDF version of this assignment is attached.I'll also put it in the Assignments folder in Files.As usual, you'll answer the questions in the online version.That version will be available for you to open at noon today (Friday 7/31) and will remain open until midnight on Tuesday (8/4).As usual, there are some minor difference between the online version and the PDF version.

This assignment will require you to number of single-payment bond pricing (present value) calculations of the type you did in Assignment 2, Part B-2.Please round the answers to the nearestcent.For interest rates, round to the nearest tenth of a percent, unless otherwise indicated.

For Part D, Question 1.A, you'll need to use a set of discount tables that I will attach to a separate announcement.You may also want to review the example I went through near the the end of my second recorded lecture on Major Topic 1, Part D; the subject was "calculation costs."

Also for Part D, remember that the value you should use for the term is theremainingterm: the amount of time left before the bill comes due.In Question 1.B, when you are doing present value calculations (as opposed to using the table), this value should be measured in years, or in fractions of years.

For Part E, it may be helpful to review pp. 59-69 of my Lectures1-E notes pretty carefully.But please note that I want you to calculate the exact market values of the assets and liabilities by doing present value calculations.

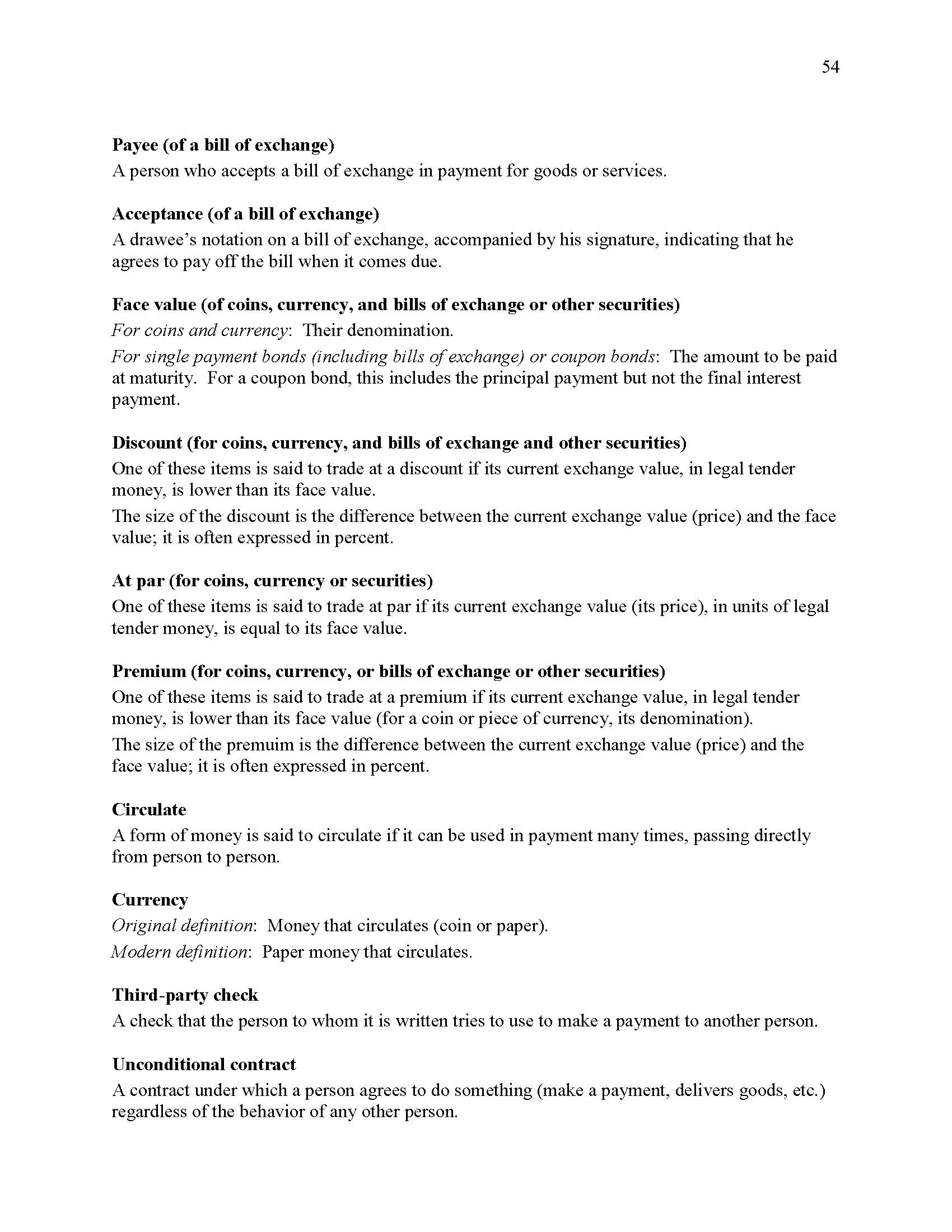

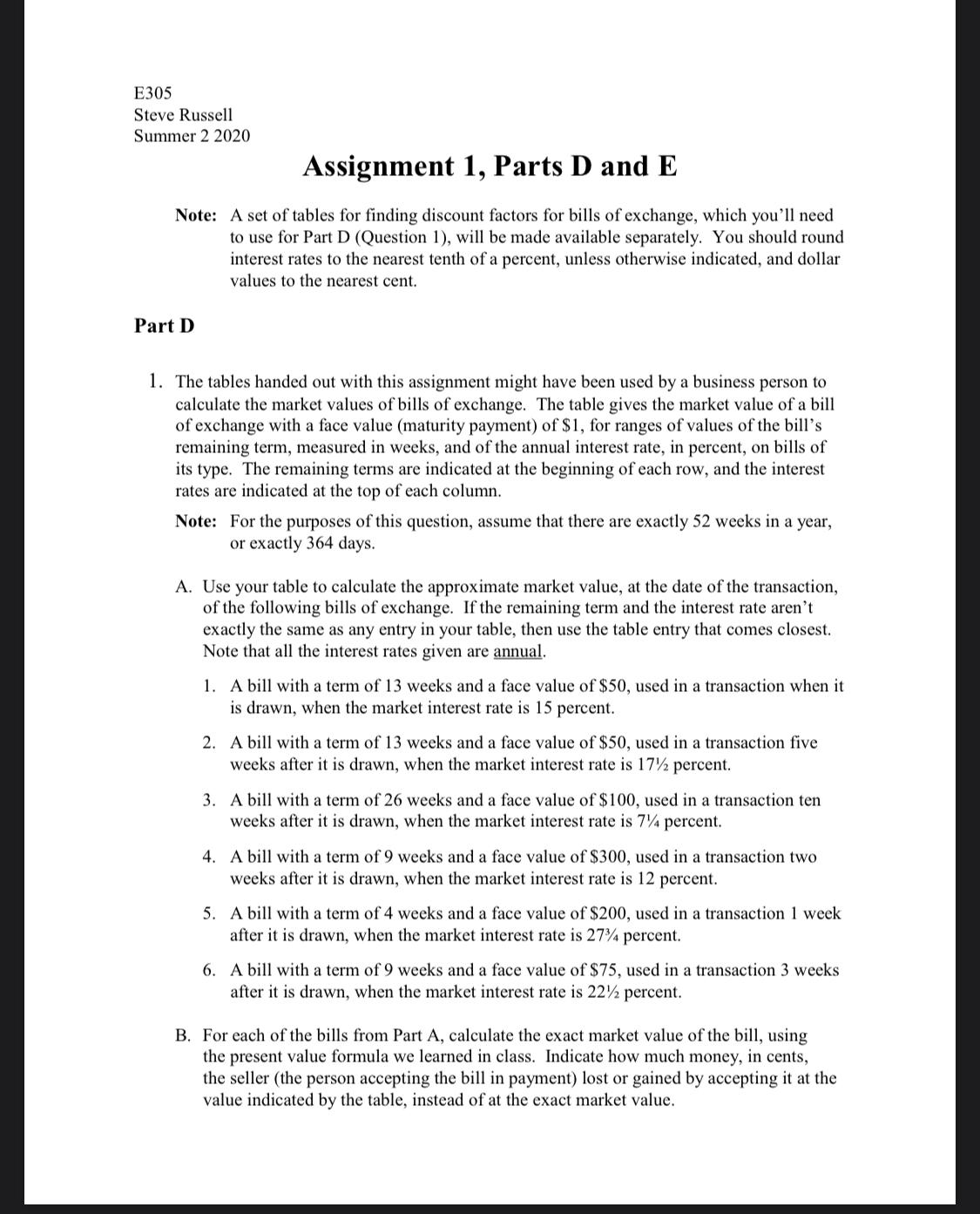

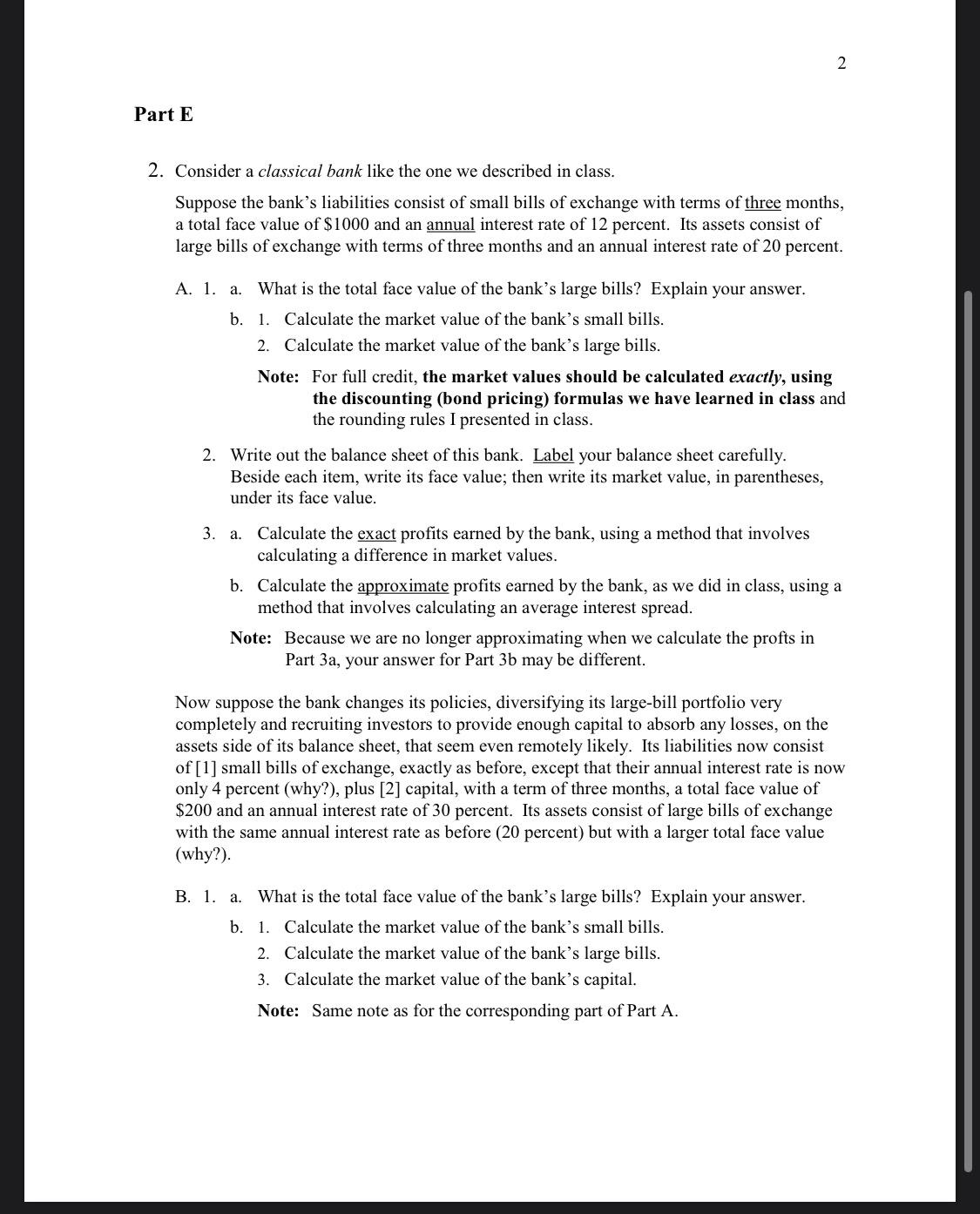

D. The development of paper money 1. Introduction As we have seen, a serious problem with using gold and/or silver coins as money was the problem of portability and security for large payments. As economies developed, relatively large payments became increasingly common. Although small quantities of gold and silver were sufcient for many payments, for large payments the quantities required were heavy and bulky, which made them difcult to transport, conceal or protect. One solution to this problem that occurred to people at an early stage was to use paper as money, in some form. Of course, paper couldn't be used, directly, as commodity money: it wasn't sufciently valuable relative to other goods. But it might be possible to associate particular pieces of paper with particular quantities of gold and silver coins i perhaps, large quantities. It might then be possible to trade ownership of the coins by trading the pieces of paper, rather than the coins themselves, which could remain stored in secure locations. It also seemed possible that it might not be necessary to invent pieces ofpaper that had this characteristic (known value in terms of gold or silver coins), because they already existed. In an economy sophisticated enough to produce many large payments, there is also likely to be a good deal of lending and borrowing. When an economic agent lends, especially when they loan is for a fairly large amount, the agent is likely the require the borrower to sign a document that records the identity of the lender and the borrower, amount borrowed, the amount(s) of the promised repayments, and the date(s) of these repayment(s). This document is called a promissory note: a paper record of the terms of a credit agreement. One way it might be possible for a lender to make a payment for a large purchase, as an alternative to using cash (specie), would be to sign a promissory note over to the seller (endorsing it). The borrower would then make any remaining payments to the seller, rather than to the original lender. Although promissory notes were occasionally used to make payments, they never became popular enough, for this purpose, to be considered a form of money. The main reason for this, somewhat ironically, was that their denominations were too large. Loan transactions are usually for larger amounts than regular business transactions. So promissory notes were useful for really large payments, but there was a broad range of intermediate-size payments for which the denomination of most promissory notes was too large to be convenient, and the quantity of gold and silver needed to make the payments was also too large to be convenient. This problem led to the development of a modied form of promissory note called a bill of exchange. Bills of exchange were the rst paper money, or, at least, an early form of paper money. 41 2. Bills of exchange: an example The setting for this example is the early 1800s, shortly after the United States achieved independence from England. A furniture manufacturer in Baltimore sells his furniture in a number of nearby cities, including Washington DC. Baltimore is roughly 35 miles from Washington DC. This distance was far enough to require a travel time of at least a day, given the transportation technology available at the time. But it was short enough to allow active trade between the two cities. For the purposes f this example, we'll imagine that Baltimore was a local center for furniture manufacturing. Furniture manufacturers in Baltimore would sell furniture, wholesale, to merchants in Baltimore and elsewhere, who would sell it, retail, to consumers and rms. We'll imagine that a particular furniture manufacturer sends an employee to Washington, from time to time, to drum up business and for related purposes. In the language of the day, this employee might have been described as the furniture maker's agent (or business agent). After the agent reaches Washington, he will probably start his work by talking to a number of different merchants in the city, hoping to nd one or more merchants who are interested buying furniture manufactured by his employer. Next, we'll imagine that the agent nds a merchant who is interested. They spend some time discussing the types and quantities of furniture the merchant wants, and negotiating prices. Ultimately, they reach an agreement. The agreement is recorded in the form of two documents: a delivery contract and a payment contract. The delivery contract species the types and quantities of furniture the merchant wishes to buy, and it species a delivery date. The payment contract species the total amount the merchant will pay for the furniture, and it species the payment date, which is likely to the same as the delivery date. For purposes of simplicity, we'll assume that the amount is $1000 and that the delivery/payment date is 90 days (three months) in the future. Each contract must be signed by both parties: the merchant and the agent, who signs on behalf of his employer. Each party keeps a signed copy of each agreement. These contracts have two curious features. First, why are there two of them? It would seem more natural for there to be a single contract with two sections: a delivery section and a payment section. An even more curious feature is that both contracts are unconditional. The delivery contract simply requires the furniture maker to deliver the furniture at a particular date; there is no clause allowing him to refuse to deliver it if h is not paid. The payment contract simply requires the merchant to pay $1000 to the furniture maker (or his agent) at a particular date. There is no clause allowing him to refuse to pay if the furniture is not delivered. Notice that the payment contract is a type of promissory note: the merchant agrees to pay the furniture maker a xed sum at the end of a xed term (three months). 42 Why are the two contracts unconditional? It would seem more natural for there to be a single contract under which both the payment and the delivery are conditional: the merchant is obliged to pay only if all the furniture is delivered, and the furniture maker is obliged to surrender the furniture only if the merchant pays in full. It's a good question, but we need to put it off until a bit later in our story. As we have indicated, the furniture maker's agent is more than just a sales person. His employer also expects him to look around, while he is in Washington, for good deals on any of the inputs he needs to manufacture furniture. If an important input is available at a low enough price, it might make sense to buy it in Washington, even though it would have to be transported to Baltimore. One of the inputs needed for furniture is varnish. Weill imagine that the agent nds a varnish maker who is selling the right kind of varnish at a very attractive price. He negotiates with the varnish maker until they agree on a price and a quantity. The price of the varnish will be $10 per gallon, and the merchant will buy roughly ve gallons of varnish at that price. (Why \"roughly\"? See below.) The next question is: How will the agent pay for the varnish? The agreement with the merchant did not allow him to collect any cash up front. His employer did not give him any large amount of cash to carry to Washington: only enough to cover is expenses for food and lodging. He may have been afraid that the agent might get robbed on the trip, or that being entrusted with a large amount of cash might tempt the agent to disappear with it. So the agent needs to pay for the varnish, but he does not have any cash on hand. He does have the promissory note signed by the merchant. In principle, he could use it to make the payment, signing it over to the varnish maker. But the varnish maker would have to give him roughly $950 in change, in cash, which he would have to carry back to Baltimore. The varnish maker probably doesn't have anything like that much cash on hand, and the agent's employer would be very unhappy for the agent to be carryng that much of his cash around. The denomination of the promissory note is too large for a payment of this size. It turns out, however, that the agent will use the promissory note as the basis for an alternative strategy for making the payment. He takes a blank piece of paper out of his bag and draws up another document, which will be called a \"bill of exchange.\" The agent writes an amount on the bill: $50. Next, he adds text to the bill which says that the merchant from the furniture transaction will pay this amount in cash [specie], in 90 days (at the same date the promissory note is due), to any person who presents the bill to him. The agent intends to pay for the varnish by giving this bill to the varnish maker, who can collect the $50 from the merchant in 90 days. In effect, he is \"chipping off\" $50 from the $1000 the merchant owes his employer and using it to make a payment on his employer's behalf. He will 43 probably show his copy of the promissory note to the varnish maker, in order to assure him that the merchant will cover the bill when it comes due. But this will not be enough to satisfy the varnish maker. So the agent will go back to the merchant and ask him to sign the bill of exchange, writing \"accepted\" under his signature. This action signies that the merchant has agreed to cover the bill. At the same time, both the merchant and the agent note, on their copies of the promissory note (perhaps on a blank reverse side), that the debt the merchant owes to the furniture maker has now been reduced to $950. Each party initials this notation on the copy of the note that belongs to the other party. The agent will now take the accepted bill and go back to the varnish maker, offering it in payment for the varnish. The varnish maker, seeing the merchant's signed acceptance, is now likely to agree to take the bill in payment. He signs the bill, signifying that he agrees to accept it in payment. He then gives the varnish t0 the agent, who will take it with him back to Baltimore or arrange to have it shipped there. It was once very common to use bills of exchange to make payments so common that the bills were considered to be a form of money. Some terminology: In the language that was used at the time bills of exchange were popular, the person who wrote up a bill and offered it in payment (the agent, in our example) was said to have \"drawn\" the bill; he was called the drawer. The person who agreed to pay off the bill because he owed money to the drawer or his employer (the merchant, in our example), was called the drawee; the bill was said to be \"drawn against\" him. The person who agreed to take a bill in payment for goods or services (the varnish maker, in our example) was called the payee, and the bill was said to be \"drawn in his favor.\" You already may have noticed that there is a strong similarity between making a payment by drawing a bill of exchange and making a payment by writing a check. The similarity is so strong that we may think of bills of exchange as the ancestors of checks, at least in many respects. The drawer in a bill transaction corresponds to the check-writer in a check transaction: the check-writer writes out a document (on a modern check, much of the information is preprinted) that instructs someone else [his bank] to pay a person he designates an amount he species. The drawee in the bill transaction corresponds, for the check transaction, to the check-writer's bank. The bank owes the check-writer money , the balance in his checking account , and will pay some or all of this money to the person indicated on the check when the check is presented to it. The payee in the bill transaction corresponds, of course, to a person who agrees to take a check in payyment. This person will obtain nal payment in cash, or something equivalent, from the check-writer's bank.1 1 The payee may deposit the check, in which case funds from the checkwriter's checking account will be transferred to his checking account, or he may cash the check, in which case he will collect the funds in cash. 44 The promissory note from the bill-of-exchange transaction corresponds to the checking account from the check transaction. The drawer can draw a bill because the drawee owes a debt to him, or to his employer, in the amount of the promissory note, which is the maximum size of the bill(s) he can draw. A check-writer can write a check because a bank owes him money , money he deposited in his checking account. The balance in the account is the maximum size of the check(s) he can write. Finally, the bill of exchange plays the role of a check. 3. Important characteristics of bills of exchange: Although bills of exchange were similar to checks in many important ways, they were different in other ways that are also important. In this section, we will discuss two key characteristics of bills of exchange that were quite different from the characteristics of modern checks. Discounts Recall that, in our story about using a bill of exchange to make a payment, we said that the agent used a bill of exchange with a face value (payoff value) of $50 to buy an amount of varnish whose total price was \"roughly\" $50. Could we have been more specic? Should the total price of the varnish have been exactly $50, so that the agent bought ve full gallons of varnish at $5 per gallon? Or should the total price of the varnish have been less than $50, in which case the agent purchased a bit less than ve gallons? In fact, the amount of varnish the agent will have been able to purchase will be a bit less than five gallons. So the market value of the bill of exchange 7 the value of the goods or services it can be used to purchase , will have been a bit less than $50. Why? It's also important to recall, in this connection, that the varnish maker in our story (the payee) can't collect the cash the bill promises until the end ofthe bill's term: 90 days, in our example. But he gives up the varnish, immediately. It is just as if the varnish maker has lent the agent (the drawee) money, which the agent has turned around and used to buy varnish. The only difference is that the varnish maker's loan to the agent will be repaid, at the end of its term (the bill's term), by the merchant (the drawee) instead of the agent. Thus, a person who accepted a bill of exchange in payment for goods was essentially making a short-term loan, to the drawer, for the amount of the purchase. People who make loans typically expect some interest; this is true even of loans for small amounts and/ or with short terms. But bills of exchange were written to provide for fixed payments at the end of their terms, not fixed payments plus interest. So the payee would arrange to get interest by lending an amount that was a little smaller than the face value of the bill that is, by accepting the bill in exchange for a quantity of goods or services whose cash value was slightly smaller than the bill's payoff value. The difference between the market value of a bill and its payoff value was called the discount on 45 the bill. It was usually expressed as a percentage of the bill's face value. So if a bill with a face value of $50 could be used to purchase goods worth $48, then the discount of the bill was four percent. This is the rst key characteristic of bills of exchange: they traded at discounts. The size of the discount depended on the term of the bill and on the current market interest rate on bills of exchange of that type. We will study the precise relationship between these factors later in the semester, when we discuss securities pricing. Certain aspects of this relationship are pretty clear, however. A longer term produced a larger discount, other things equal: interest is charged per period of time. Similarly, a higher interest rate produced a larger discount. The interest rate on a bill would be determined partly by the risk characteristics of the bill's drawee and partly by the current state of the short-term loan market. Modern checks do not trade at discounts. If you write a check for $50 at a grocery store then you expect to get exactly $50 worth of groceries, at the posted prices. Why are checks different from bills of exchange, in this respect? The main reason is that checks clear so quickly. The interval from the time the check is written to the time when money from the check-writer's bank is transferred to the payee (or its bank) is usually just a day or two. This interval isn't long enough to justify charging interest. There was a time in our history, however, when many checks did trade at discounts. In the nineteenth century, when transportation and communication were much slower and more difficult than they are today, a check drawn on a bank from a different region of the country, or even just a different state, might take weeks or even months to clear. So many merchants charged a discount on checks from out-of-state banks that reected the average time it took checks from the state or region in question to clear. This practice largely disappeared in the 20th century, partly because of improvements in transportation and communication technology, and partly because one of the jobs of the Federal Reserve System, the federal government monetary agency that was established early in the century, was to help private banks clear checks. Eliminating discounting of checks (\"non-par banking\") was one of the goals the System was intended to accomplish. Circulation In our example, the varnish maker (the payee) accepted a bill of exchange in payment or some varnish. What was he likely to do with the bill? One possibility was for him to hold on to the bill until the end of its term, and then demand payment from the merchant (the drawee). More often, however, well before the bill's term ends 7 perhaps in a few days, or a week or two i the varnish maker would use it to make another payment, perhaps for some input that was needed to make varnish, such as turpentine. He could do this by signing the bill on its reverse side (endorsing it), signifying that he had surrendered his claim to it. The turpentine maker, in turn, 46 could use the bill to make a payment for something he needed, and so on. So a bill with a term of three months might be used to make payments a dozen times, or more, before it reached the end of its term. At that point, the last person who took the bill in payment would take it to the drawee, who would pay off the bill. More terminology: When pieces of money (coin or paper) are used repeatedly in payment, passing \"from hand to hand,\" they are said to circulate. At the time bills of exchange were popular, any form of money that circulated readily was categorized as currency. So coins were considered to be a type of currency, and bills of exchange were an early form (perhaps the first form) of paper currency. More recently, the terminology has changed. The term \"currency\" is now reserved for paper money that circulates. Coins are considered a separate category. Modern checks are not considered to be currency, and neither are the demand deposits they are drawn on, even though the balances in these accounts are considered to be \"money\" for the purpose of dening the most widely used money supply measure (M1). The reasons checks and/or demand deposit balances are not considered to be currency is that checks do not circulate very readily. If someone writes a check to you, then it is usually almost impossible for you to get someone else to accept this check in payment. Attempting to do this is often called \"trying to pass a third-party check.\" (The \"third party\" is the person or institution who originally wrote the check, but who is not around when the payee tries to pass it along as payment.) It is possible, in principle, to cash third-party checks. Suppose your friend writes a check to you, as payment for something, and you pass the check along to me, as payment for something else. If I agree to accept the check, then I will try to deposit the check in my checking account. My bank will send the check to your friend's bank (often, Via a Federal Reserve bank). If s/he has sufficient funds in his or her checking account, then the check will clear: the funds will be transferred to my checking account, and you really will have paid me. Given that this is possible, why is it very difcult to pass most third-party checks 7 so difficult that checks are not considered to be a form of currency? The answer grows out of the fact that it is also possible, in the above example, that your friend will not have sufcient funds in his or her checking account (funds equal to or exceeding the amount of the check). This could be because your friend made a mistake, or because s/he deliberately wrote a check s/he knew to be \"bad.\" In that case, your friend's bank will not honor the check: it will not transfer any funds to my bank, and my bank will not transfer any funds to my account. In this case, you will not have paid me. Of course, the same thing can happen in a regular (second-party) check transaction. The check- writer can turn out not to have sufcient funds in his or her (or its) account, in which case the check will not clear and the person who took the check in payment will not actually get paid. 47 Merchants who accept checks in payment regularly are well aware of this possibility, and they usually take steps to try to limit their losses. Suppose, for example, that you write a check to pay for groceries. Typically, the checkout clerk will ask you for identication 7 most often, your driver's license 7 before accepting the check. S/he will compare your face to the picture on the license, in order to try to verify that it really is your license. (This step doesn't always work so well.) Then s/he will write some information from the license on the check 7 your license number, and maybe your address and/or your phone number or s/he will verify that the information from your license matches the information that is already printed on the check. Of course, the checkout clerk is required to take these steps so that in case your check \"bounces\" i in case your checking account doesn't contain sufcient funds 7 the grocery store can use your ID information to pursue you for payment. If you are trying to pay your grocery store with a third-party check, however, then you are not the person the check is drawn on (the person whose bank will be asked to pay off the check). So recording or verifying your ID information will not be helpful to the bank. The person whose ID information would be helpful is the person who wrote the check (the third party). But that person isn't present. It's unlikely that you have his or her ID information, and even if you did, its accuracy could not be veried by comparing it, and the check-writer's face, to the information and the picture on his or her driver's license. Consequently, if the check bounces then it may be very difcult for the store to pursue the check-writer for payment. For this reason, most merchants will not accept third-party checks, at least in most cases. Now we understand why modern checks don't circulate. But why, in contrast, did bills of exchange circulate? Part of the reason is that it was much more difcult to \"draw a bad bill.\" As we have seen, before a drawer gave a bill of exchange to a payee, he would go back to the drawee and ask him to sign and \"accept\" it. The drawee, by doing this, attested to the payee, and to anyone who took the bill in payment later, that he owed the drawer enough money to cover the bill. For a check, this would be like taking the check from our example back to your bank, before you gave it to the grocery clerk, and asking the bank to stamp it, verifying that you have enough money in you account to cover the check.2 And if the grocery store decided to pass the check along, rather than cashing it, then anyone it passed the check along to would be able to check the stamp. In this sense, a bill of exchange was a bit like a modern money order, cashier's check or traveler's check. A person who uses one of these instruments in payment purchased it from a nancial institution, and thus has already surrendered the funds necessary to cover it. So the possibility of insufcint funds does not arise. 2 This is now practical with debit cards: the system allows merchants to verify, after the card is swiped, via electronic communication, that the cardholder has enough funds in his or her checking account to cover the payment. 48 A second reason why bills circulated is that they were drawn against (old-style) merchants. Usually, these merchants were well-known in the business community. In order to do business successfully, moreover, a merchant needed to cultivate a reputation for paying his debts. The payee of a bill would usually recognize the name of the merchant it was drawn against. He might even recognize the merchant's signature, or have a copy of the signature on file. And he would usually have reason to believe, based on the merchant's reputation, that he was likely honor the bill. The same would be true of anyone to whom the bill was passed along: bills circulated almost exclusively among business people (see below). Most modern checks, in contrast, are drawn on people who may be unknown, or known only casually, by the merchants to whom they are offered in payment. The merchants don't have any particular reason to be condent that the checks will clear. This is even more true of third party checks. And since the third-party checks can't be partly \"insured\" by recording ID information, most merchants won't accept them. It's worth noting, in this connection, that some third-party checks are relatively easy to cash, or to use in payment. Examples include tax refund checks and payroll checks from large, well- known employers (such as Wal-Mart anywhere in the United States, or Eli Lilly in Indianapolis). These checks can be \"passed along\" pretty easily because the people to whom they are signed over can be virtually certain that the check-writers , the federal government or a state government, or a large, well-known firm i will cover them when they are presented to the check- writer's banks for payment. These exceptions help prove the rule. They are cases Where any person accepting the check in payment knows the check-writer, has reason to trust that the check is \"good,\" and can locate the check-writer easily without using ID information. 4. Problems with bills of exchange As we have indicated, bills of exchange were an early form, and maybe the first form, of paper money. For many relatively large transactions they were much safer and more convenient than gold and/or silver coins (specie). However, bills of exchange had a number of problems that reduced their usefulness as money. Most of these problems affected working people much more seriously than they affected business people (see below). As a result, although bills were common, and circulated fairly freely, among business people, they were rarely used by common people, who were forced to continue to use specie for almost all their payments. 49 We'll think of these problems as Transaction problems (fourth stage): However, these are problems with using bills of exchange as money, in contrast to our rst three stages of transactions problems, which were problems with using gold and silver (rst in raw form, and then in coins) as money. Divisibility As our initial example illustrated, bills of exchange were usually drawn for transactions between business people i usually, day-to-day, moderate-size business transactions, as opposed to the larger transactions that might be nanced by obtaining loans. But even moderate-size business transactions were much larger than the day-to-day transactions of most working people, who were the group that comprised the bulk of the population. Stated differently, the denominations of most bills of exchange were too large to be convenient for working people (or for business people engaged in smaller-scale or personal transactions). This was probably the biggest reason why bills of exchange were not widely used by working people, and certainly did not circulate among them. Reliability Although bills of exchange were usually drawn against well-known merchants with good nancial reputations that they were anxious to keep, it did happen, from time to time, that a drawee could not or would not pay off a bill that had been validly drawn and accepted. In this case, the bill was said to have been dishonored. This might have happened because the drawee had suffered serious business or nancial reverses and could no longer pay his debts, or because he was dishonest and had decided to try to evade them. If a merchant, went bankrupt, or had very serious nancial reverses, and this became public knowledge, then no one would accept bills of exchange drawn on him in payment. Thus, any person who had accepted a bill was taking a small risk that it would become worthless, even if there was plenty of time before it came due. Since the drawee of a bill of exchange played the same role, in a transaction involving a bill, that is played by the check-writer's bank in a transaction involving a modern check, having a bill you had taken in payment be dishonored was similar, in many ways, to being unable to cash a check you've taken in payment because the check-writer's bank has failed. This almost never happens in the modern United States. Banks very rarely fail, and even when they do, the account balances are almost always insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), a federal government agency that insures consumer accounts at banks. Earlier in our history, however, instances of this sort were much more common. The FDIC was established in 1933, at the end of the wave of bank failures that marked the worst period of the Great Depression. Prior to 1933, even before the depression, bank failures were much more common than they are 50 today. When a bank failed, moreover, a consumer might lose all or most of his deposits at the bank. Checks that had been drawn on deposits at failed banks usually couldn't be cashed, even though the check writers' accounts were recorded as containing sufficient funds. An even bigger \"reliability\" problem was that it was relatively easy for an unscrupulous person to create a counterfeit bill and use it to make a purchase. He could do this by writing out the text of the bill and then forging the signature and acceptances of a faux drawee. If a bill turned out to be forged, then the merchant it was \"drawn\" on would refuse to pay it off. And if the forgery was discovered before the bill was presented to that merchant, the last person holding the bill at the time of the discovery was left \"holding the bag.\" Although a business person who took bills in payment regularly might recognize the signatures of most local merchants who served as drawees, and might have copies of their signatures of almost all of them on file, a sufficiently artful forger could get around these precautions. Consequently, forgery of bills was a very serious problem. Governments often tried to contain it by imposing extremely harsh penalties: there were times and places where a person convicted of forging a bill could have his hand cut off, or could even be executed. Forgery of bills was similar to deliberately writing bad checks for large sums. A person who deliberately writes a bad check is fraudulently pretending that a bank owes him or her money because he has funds in an account at the bank, just as a person who drew a false bill was fraudulently pretending that a merchant owed him or his employer money to fulfill a contract for future payment (recorded as a promissory note). Forged bills of exchange imposed occasional large costs on people who took bills in payment, just as dishonored bills did, less frequently. But their effect on the usefulness of bills in payment was broader and more serious. Some business people responded to the risk that bills might be forged or dishonored by refusing to accept them in payment. But even a person who was willing to accept bills in payment was likely to charge additional interest, on the bills, to compensate himself for taking the risk. This \"risk premium\" would be reected in a deeper discount on the bill. So a bill with a face value of $50 might be accepted in payment for $47 worth of goods, instead of $49 worth, Where the extra $2 discount represents the compensation for the risk that the bill will be dishonored, or will turn out to have been counterfeited. These deeper discounts greatly increased the expense of using bills of exchange to make payments instead of using specie, which was not discounted. So they reduced the number ofpeople willing to use bills for that purpose. The reliability problems with bills of exchange were another factor that made bills unattractive to working people, who were not in a position to assess the risks associated with these problems. A business person might know the merchant a particular bill was drawn on, or he might be familiar with his reputation even if he did not know him personally. He might recognize the signature of 51 the merchant who accepted the bill, or have it on le. In all these cases, a working person usually would not. Also, a business person were likely to be familiar with the discounts other sellers were charging on bills, and he might hear, from other business people, that bills that purported to be drawn on particular merchants were actually forged. Again, most working people had neither the sources necessary to obtain this sort of information or the time needed to collect it. So they shied away from bills, unwilling to take risks whose severity they had no way of judging. There was another potential hang-up with bill-of-exchange transactions that also involved a question of reliability. As you'll recall from our example in Part 2 of this section, a bill of exchange was usually based on a business transaction that called for future delivery of goods, and future payment. The bill was \"backed\" by a contract calling for the purchaser of the goods to pay the seller for them, at or near the delivery date. Suppose, however, that the seller failed to make the delivery, and the purchaser responded by refusing to make the payment. Presumably, he would also refuse to cover any bills of exchange that were \"chipped off\" from (drawn against) that payment. It would follow that in order to be willing to accept a bill of exchange in payment, the payee would need to trust both the drawee and the seller of the goods the drawee had purchased. As we have seen, the drawee was likely to be a well-known merchant who the payee knew and reason to trust. But the payee was unlikely to know the seller, who might well be from a different city (as the furniture maker was in our example). Bottom line: if payees had needed to trust the people who sold goods to merchants in order to be willing to take bills of exchange drawn against the merchants in payment, then the pay-with-bills system probably wouldn't have worked. Most of the payees wouldn't have had the required level of trust in most of the sellers. What solved this problem was the fact that the payment contract that provided the basis for a bill of exchange was unconditional (see above). In particular, the required payment it was not contingent on delivery of the goods to the merchant. The merchant had to pay the amount specified in the contract, and thus the face value of any bills drawn against this amount, even if the seller failed to deliver the goods. So the payee on a bill only had to trust the merchant it was drawn against. But this solution raises another question: Why would a merchant who purchased goods for future delivery be willing to sign a payment contract that was unconditional? By signing such a contract, the merchant exposed himself to a signicant risk that he would end up having to pay for goods that were not delivered. The answer to this question has two parts. First, if the goods are not delivered, the merchant is not without recourse, even though he doesn't have the option of refusing to pay. He will almost certainly take the furniture maker (in our example) to court to try to force him to honor the delivery contract. Thus, the fact that we have reasonably effective legal (court, etc.) and law 52 enforcement systems, and the fact that business contracts are legally enforceable, gives our merchant a great deal more protection against non-performance by our furniture maker than he would have otherwise. Still, going to court is expensive, and courts are not 100 percent reliable: sometimes people lose cases they should have won, and vice-versa. If legal protection had been the only reason merchants might have considered signing unconditional payments contracts, most of them probably would not have done so. There must have been a positive incentive: an answer to the question \"What was in it for them?\" The answer grows out of the fact that the possibility of drawing bills of exchange on the payments contracts that resulted from sales agreements was attractive to wholesale sellers (rms, like our furniture-making firm, that might sell goods to merchants). Being able to draw bills allowed these sellers, or their representatives, to make purchases in the locations where they were making sales, even if these locations were far from their home bases. This often allowed them to buy inputs at cheaper prices, or inputs that weren't currently available at their home bases, etc. As we have just seen, however, bills of exchange could be drawn against a payment contract only if the contract was unconditional. So merchants who were willing to sign unconditional payment contracts were more popular, with wholesalers, than merchants who werenit: more wholesalers offered to sell them goods, and these wholesalers might offer them better prices than they offered merchants who were less cooperative. To summarize, it was probably competitive forces 7 competition between merchants for wholesale sellers, and for low wholesale prices 7 that motivated merchants to sign unconditional payment contracts that bills of exchange could be drawn on. Calculation costs As we have seen, the rst person who took a bill of exchange in payment (the rst payee) charged the drawer a discount that reected the interest on the bill. The size of the discount depended on the term of the bill and the current market interest rate, per period, on bills of that type. Each time a bill changed hands, the discount had to be recalculated. The remaining term of the bill was now shorter, and the market interest rate on the bill might have changed, either because there was new information about the riskiness of the bill's issuer or because there had been a change in the state of the overall short-term loan market. Calculating the discount wasnit easy, given the difficulty of the math involved (raising numbers to fractional powers) and the very limited computational technology available at the time (no computers or electronic calculators, etc.). Most people, even most business people, would have been unable to perform these calculations, particularly on short notice. Instead, they probably relied on tables, prepared in advance, that gave the percentage discounts on bills with a range of different terms over a range of different interest rates. If the term and/or rate didn't exactly 53 match a value from the table, then they'd either pick the closest value(s) on the table, or try to interpolate. The need to calculate the discount on a bill each time it was used in payment added to the time needed to complete any transaction conducted with a bill. It also increased the difficulty and risk of using bills in payment or accepting them in payment. If you didn't have a discount table handy then you might turn away a bill, possibly passing up a sale. Or, you might try to guesstimate the size of the discount, which could lead you to make a large mistake. It was also fairly easy to make a mistake even if you did have access to a discount table. You might choose the wrong row or column or misinterpolate between them. And even if you got the right percentage from the table, you still had to apply the percentage to the face value correctly in order to calculate the discount. The inconveniences, difficulties and risks associated with calculating the discounts on bills probably made many merchants reluctant to accept bills in payment, and they probably caused many people who might have been inclined use a bill in payment to decide to use specie instead. So they reduced both the effectiveness and the popularity of bills as a method of payment. And they were one more nail in the cofn of the use of bills by working people. Most working people had no idea how to do the calculations involved, very few owned or had access to discount tables. Denitions Promissory note A document that records the terms of a credit (lending/borrowing) agreement. Endorsement The act of signing a nancial instrument, indicating thereby that the signer has given up claim to the payments s/he is entitled to under the agreement the instrument records. Bill of ex ehan ge A document that records an agreement by a person (the drawee) who owes funds to another person (the drawer), as part of a commercial transaction, to pay part of that debt to a third person (the payee). Drawer (of a bill of exchange) A person who writes out a bill of exchange and uses it to purchase goods or services. [This person is said to have drawn the bill.] Drawee (of a bill of exchange) A person who agrees to transfer payment of part of a debt to the person who is paid using a bill of exchange. [The bill is said to be drawn against this person] 54 Payee (of a bill of exchange) A person who accepts a bill of exchange in payment for goods or services. Acceptance (of a bill of exchange) A drawee's notation on a bill of exchange, accompanied by his signature, indicating that he agrees to pay off the bill when it comes due. Face value (of coins, currency, and bills of exchange or other securities) For coins and currency: Their denomination. For Single payment bonds (including bills of exchange) or coupon bonds: The amount to be paid at maturity. For a coupon bond, this includes the principal payment but not the final interest payment. Discount (for coins, currency, and bills of exchange and other securities) One of these items is said to trade at a discount if its current exchange value, in legal tender money, is lower than its face value. The size of the discount is the difference between the current exchange value (price) and the face value; it is often expressed in percent. At par (for coins, currency or securities) One of these items is said to trade at par if its current exchange value (its price), in units of legal tender money, is equal to its face value. Premium (for coins, currency, or bills of exchange or other securities) One of these items is said to trade at a premium if its current exchange value, in legal tender money, is lower than its face value (for a coin or piece of currency, its denomination). The size of the premuim is the difference between the current exchange value (price) and the face value; it is often expressed in percent. Circulate A form of money is said to circulate if it can be used in payment many times, passing directly from person to person. Currency Original denition: Money that circulates (coin or paper). Modern denition: Paper money that circulates. Thirdparty check A check that the person to whom it is written tries to use to make a payment to another person. Unconditional contract A contract under which a person agrees to do something (make a payment, delivers goods, etc.) regardless of the behavior of any other person. E305 Steve Russell Summer 2 2020 Assignment 1, Parts D and E Note: A set of tables for nding discount factors for bills of exchange, which you'll need to use for Part D (Question 1), will be made available separately. You should round interest rates to the nearest tenth of a percent, unless otherwise indicated, and dollar values to the nearest cent. Part D l. The tables handed out with this assignment might have been used by a business person to calculate the market values of bills of exchange. The table gives the market value of a bill of exchange with a face value (maturity payment) of $1, for ranges of values of the bill's remaining term, measured in weeks, and of the annual interest rate, in percent, on bills of its type. The remaining terms are indicated at the beginning of each row, and the interest rates are indicated at the top of each column. Note: For the purposes of this question, assume that there are exactly 52 weeks in a year, or exactly 364 clays. A. Use your table to calculate the approximate market value, at the date of the transaction, of the following bills of exchange. If the remaining term and the interest rate aren't exactly the same as any entry in your table, then use the table entry that comes closest. Note that all the interest rates given are annual. 1. A bill with a term of 13 weeks and a face value of$50, used in a transaction when it is drawn, when the market interest rate is 15 percent. 2. A bill with a term of 13 weeks and a face value of$50, used in a transaction ve weeks after it is drawn, when the market interest rate is 17% percent. 3. A bill with a term of26 weeks and a face value of$100, used in a transaction ten weeks after it is drawn, when the market interest rate is \"M percent. 4. A bill with a term of 9 weeks and a face value of $300, used in a transaction two weeks after it is drawn, when the market interest rate is 12 percent. 5. A bill with a term of4 weeks and a face value of $200, used in a transaction 1 week after it is drawn, when the market interest rate is 23% percent. 6. A bill with a term of 9 weeks and a face value of $75, used in a transaction 3 weeks after it is drawn, when the market interest rate is 22% percent. B. For each of the bills from Part A, calculate the exact market value of the bill, using the present value formula we learned in class. Indicate how much money, in cents, the seller (the person accepting the bill in payment) lost or gained by accepting it at the value indicated by the table, instead of at the exact market value. Part E 2. Consider a classical bank like the one we described in class. Suppose the bank's liabilities consist of small bills of exchange with terms of three months, a total face value of $ 1000 and an annual interest rate of 12 percent. Its assets consist of large bills of exchange with terms of three months and an annual interest rate of 20 percent. A. 1. a. What is the total face value of the bank's large bills? Explain your answer. b. 1. Calculate the market value of the bank's small bills. 2. Calculate the market value of the bank's large bills. Note: For rll credit, the market values should be calculated exactly, using the discounting (bond pricing) formulas we have learned in class and the rounding rules I presented in class. 2. Write out the balance sheet of this bank. Label your balance sheet carefully. Beside each item, write its face value; then write its market value, in parentheses, under its face value. 3. a. Calculate the ext profits earned by the bank, using a method that involves calculating a difference in market values. b. Calculate the approximate prots earned by the bank, as we did in class, using a method that involves calculating an average interest spread. Note: Because we are no longer approximating when we calculate the profts in Part 3a, your answer for Part 3b may be different. Now suppose the bank changes its policies, diversifying its large-bill portfolio very completer and recruiting investors to provide enough capital to absorb any losses, on the assets side of its balance sheet, that seem even remotely likely. Its liabilities now consist of [1] small bills of exchange, exactly as before, except that their annual interest rate is now only 4 percent (why?), plus [2] capital, with a term of three months, a total face value of $200 and an annual interest rate of 30 percent. Its assets consist of large bills of exchange with the same annual interest rate as before (20 percent) but with a larger total face value (why?). B. 1. a. What is the total face value of the bank's large bills? Explain your answer. b. 1. Calculate the market value of the bank's small bills. 2. Calculate the market value of the bank's large bills. 3. Calculate the market value of the bank's capital. Note: Same note as for the corresponding part of Part A

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts