Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

A Perfect Storm: Examining the Supply Chain for N95 Masks during COVID-19 Demand is such that people are placing orders with everyone-tough to know

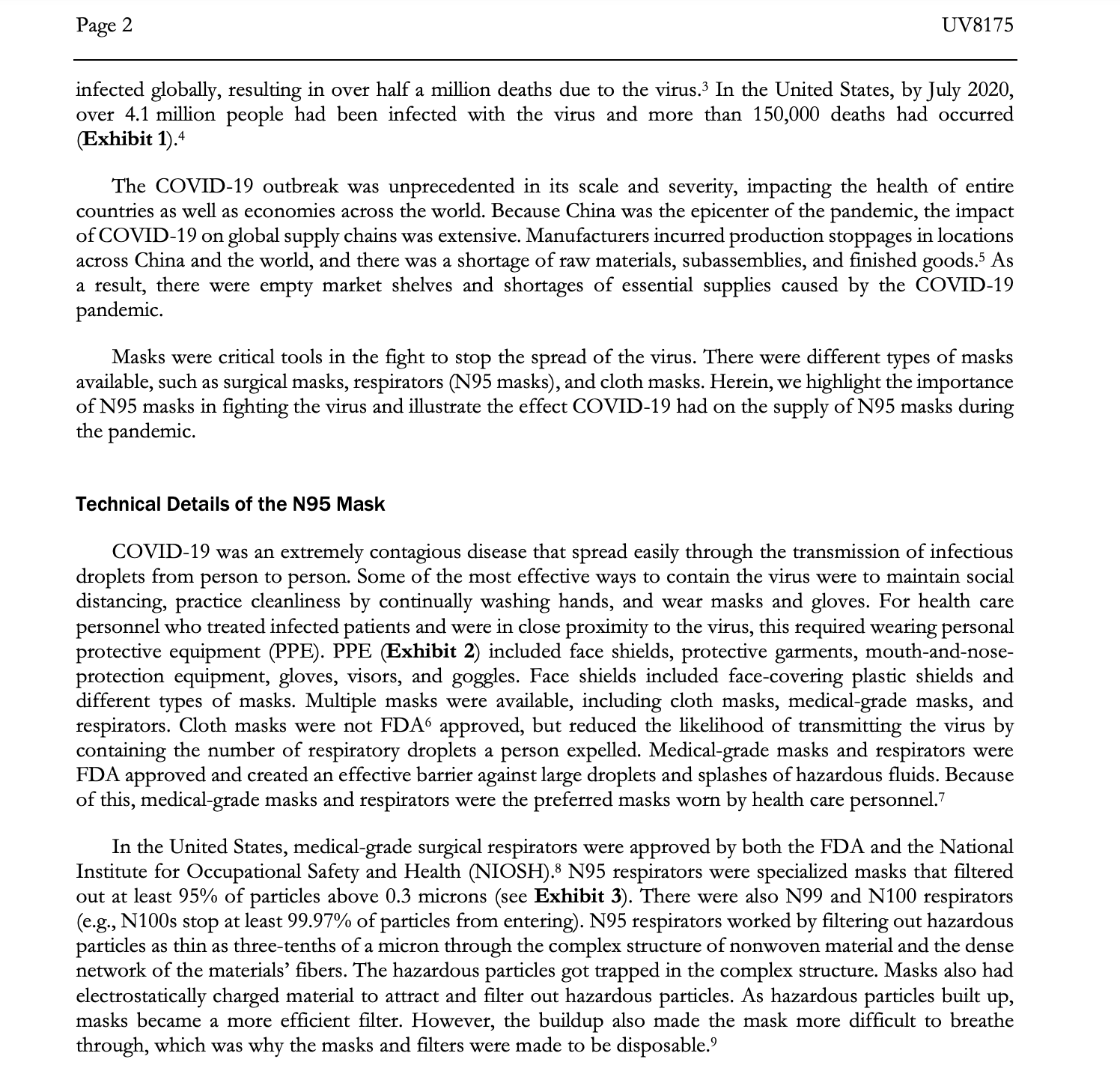

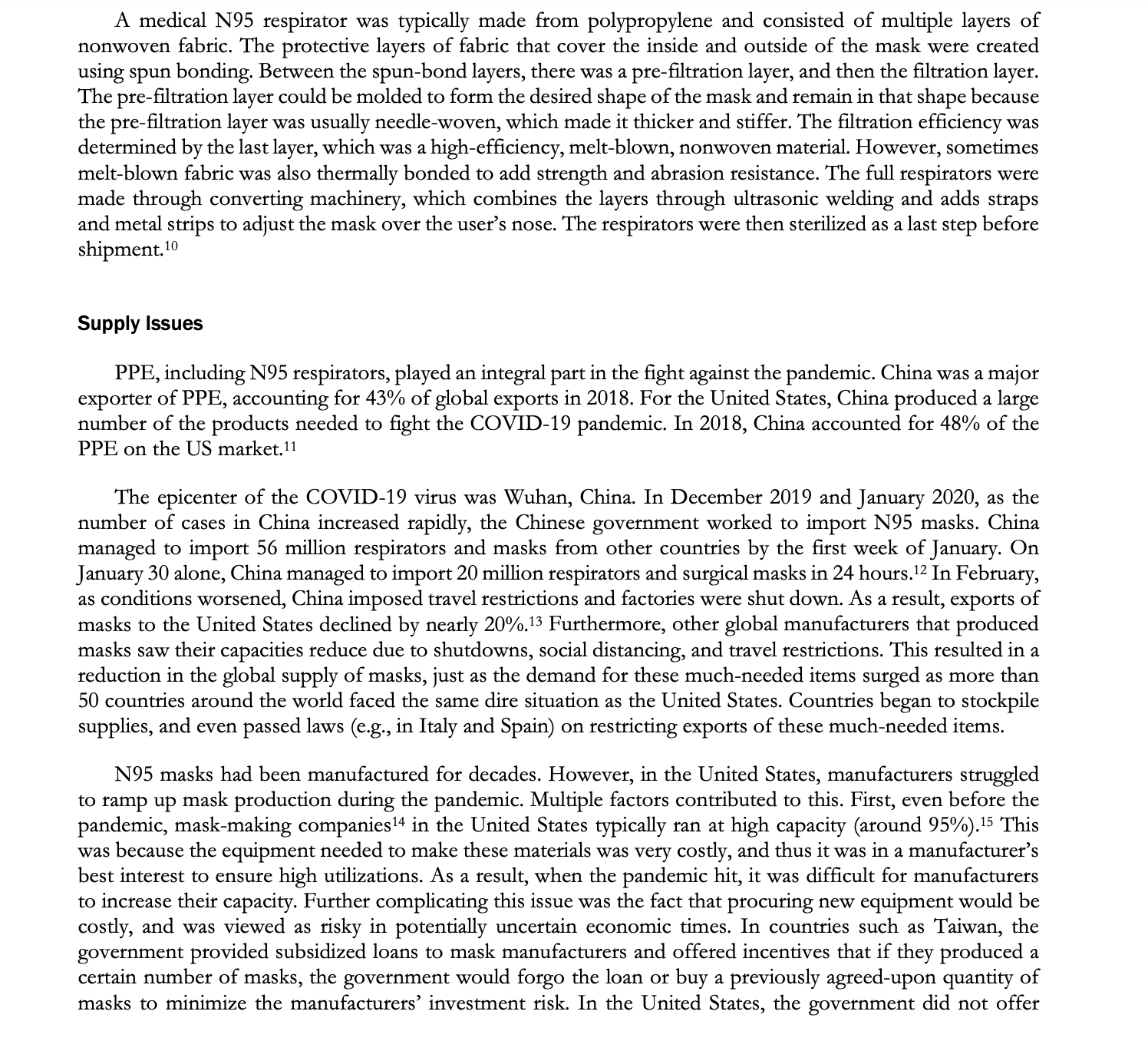

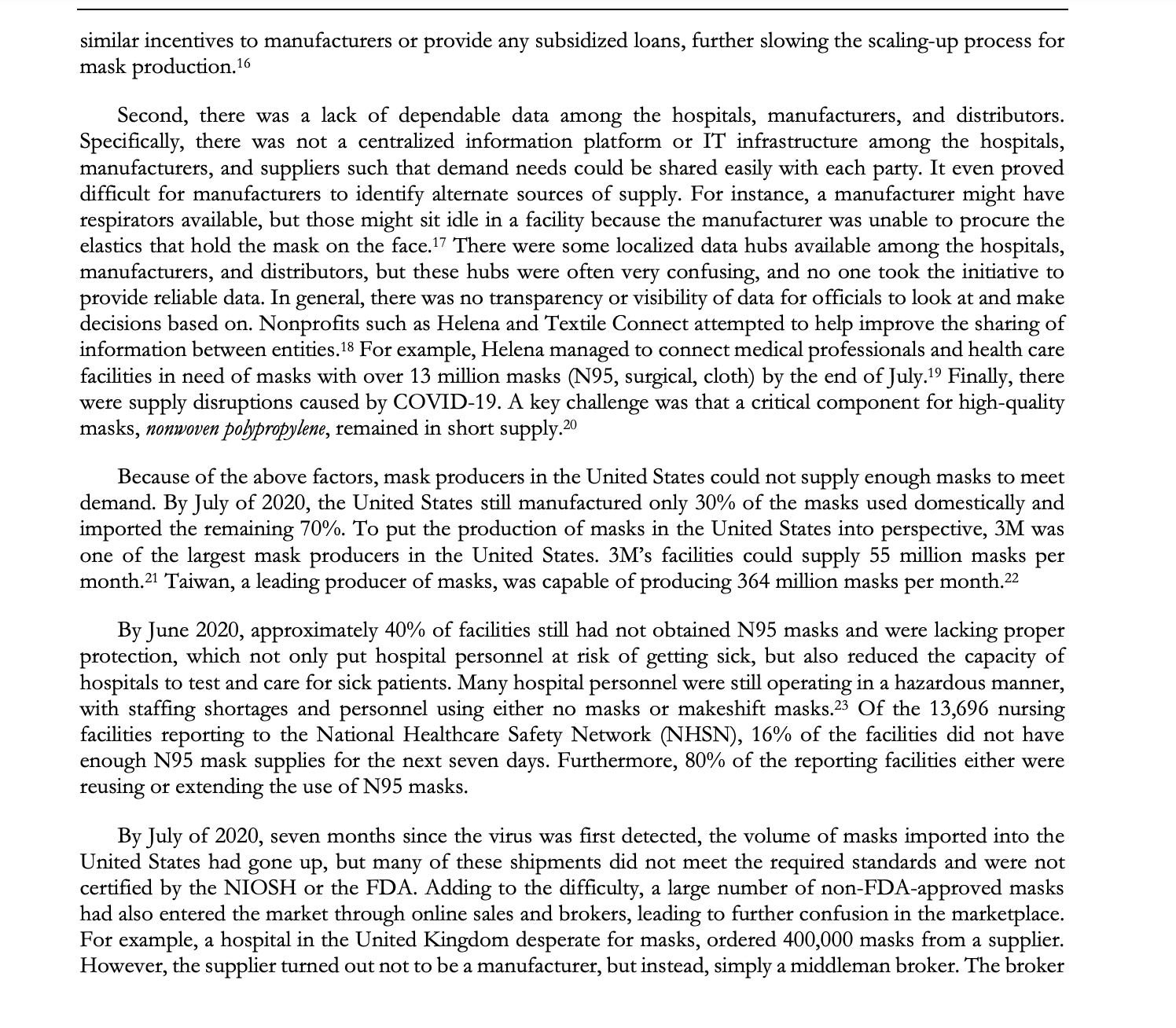

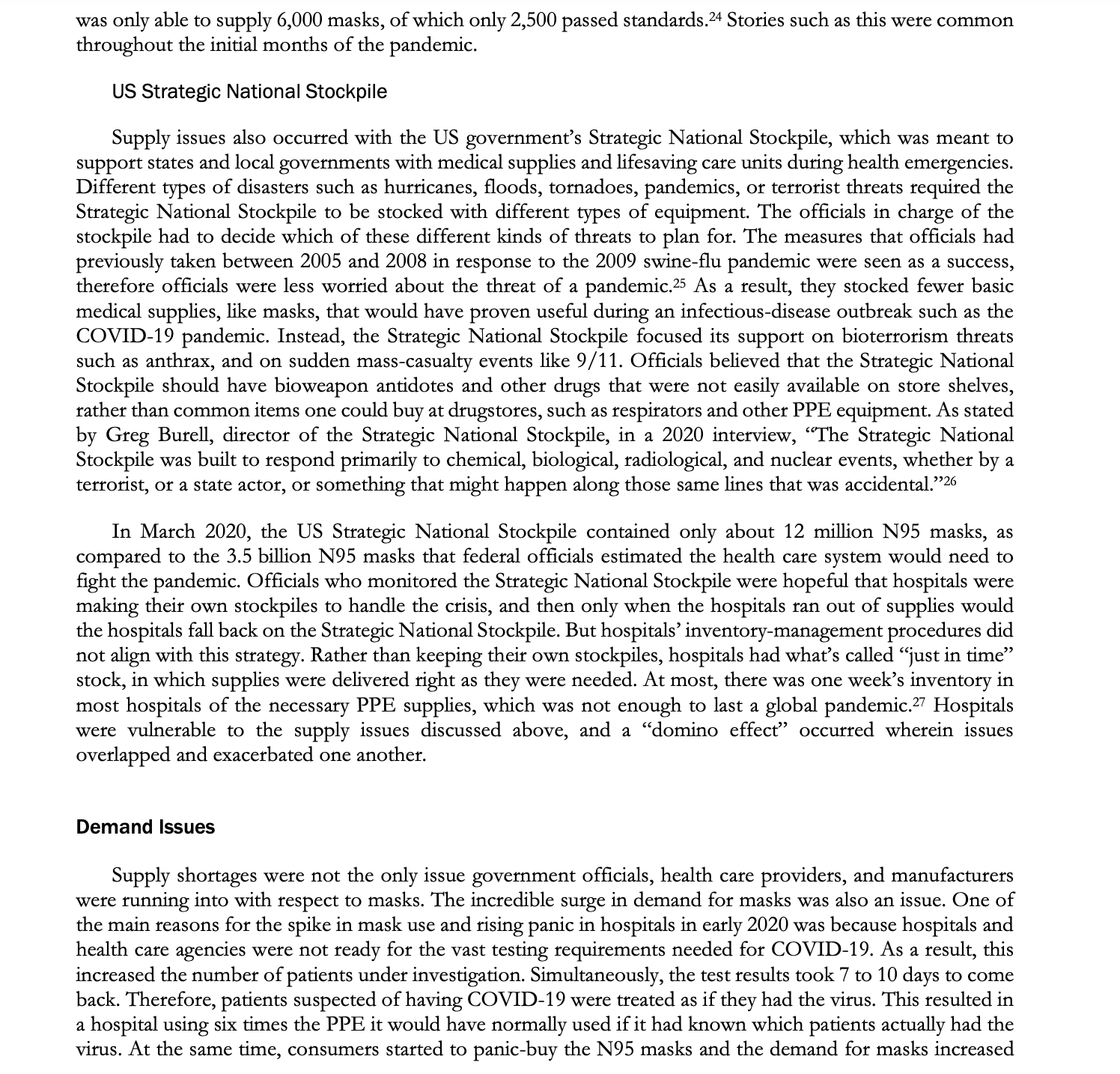

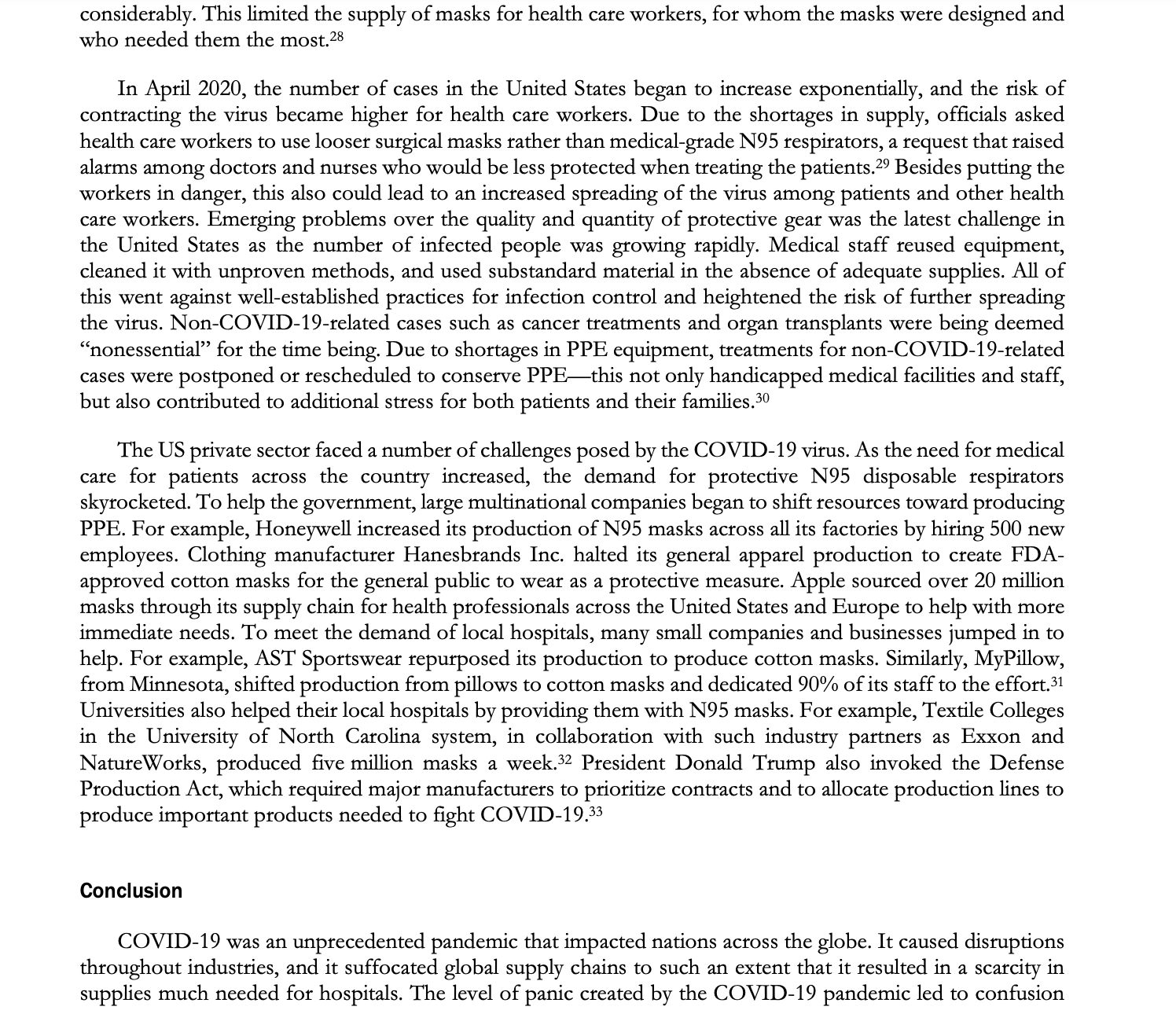

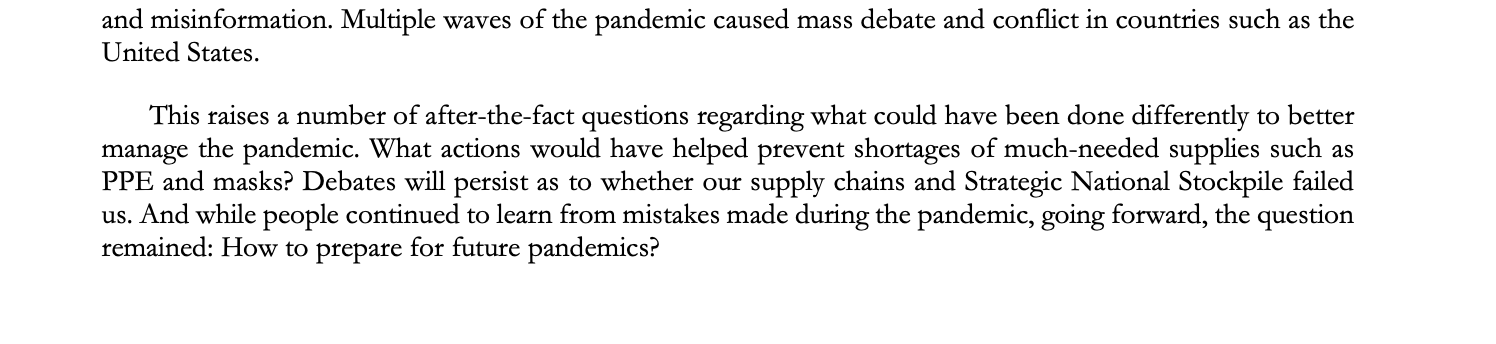

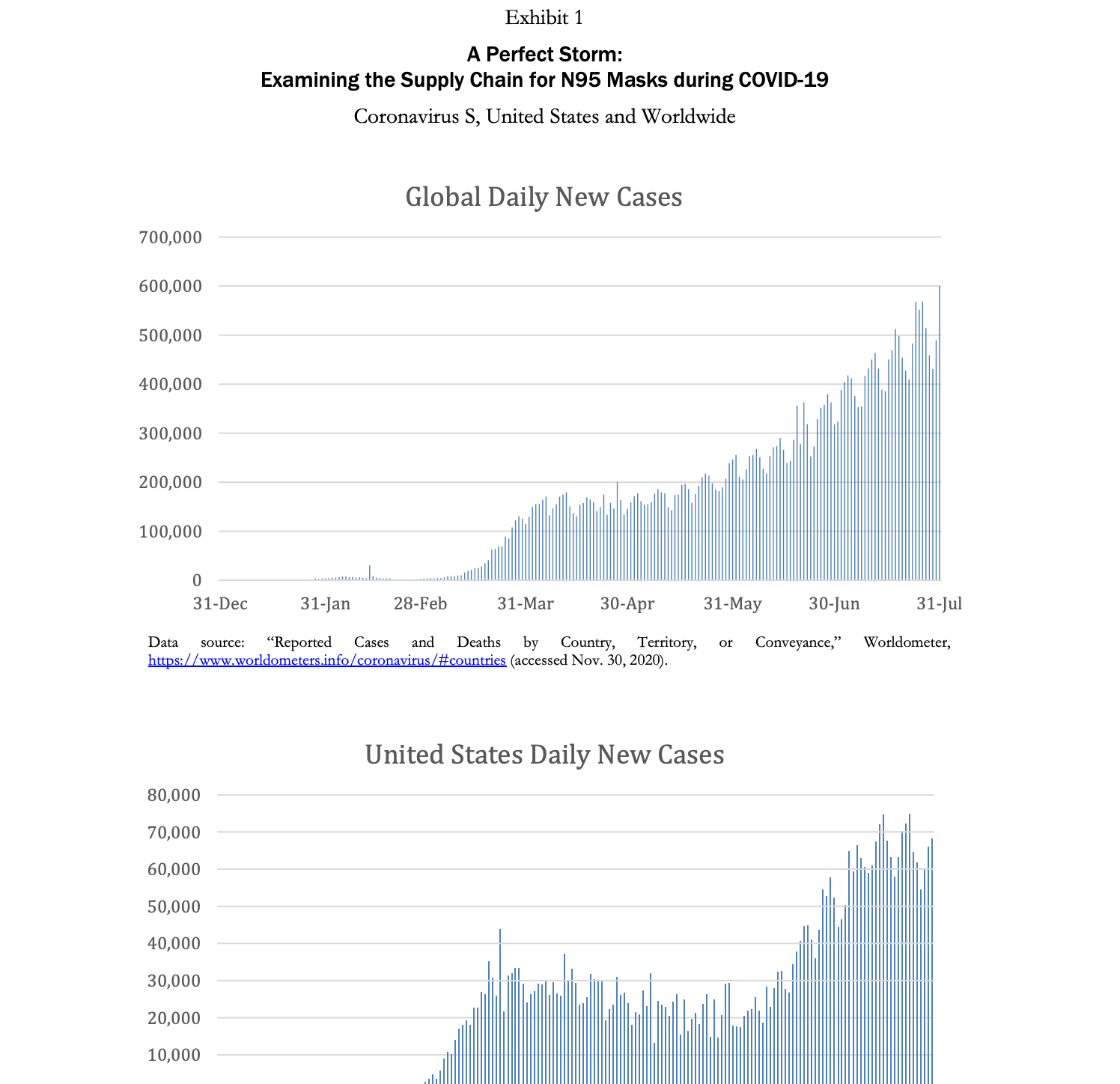

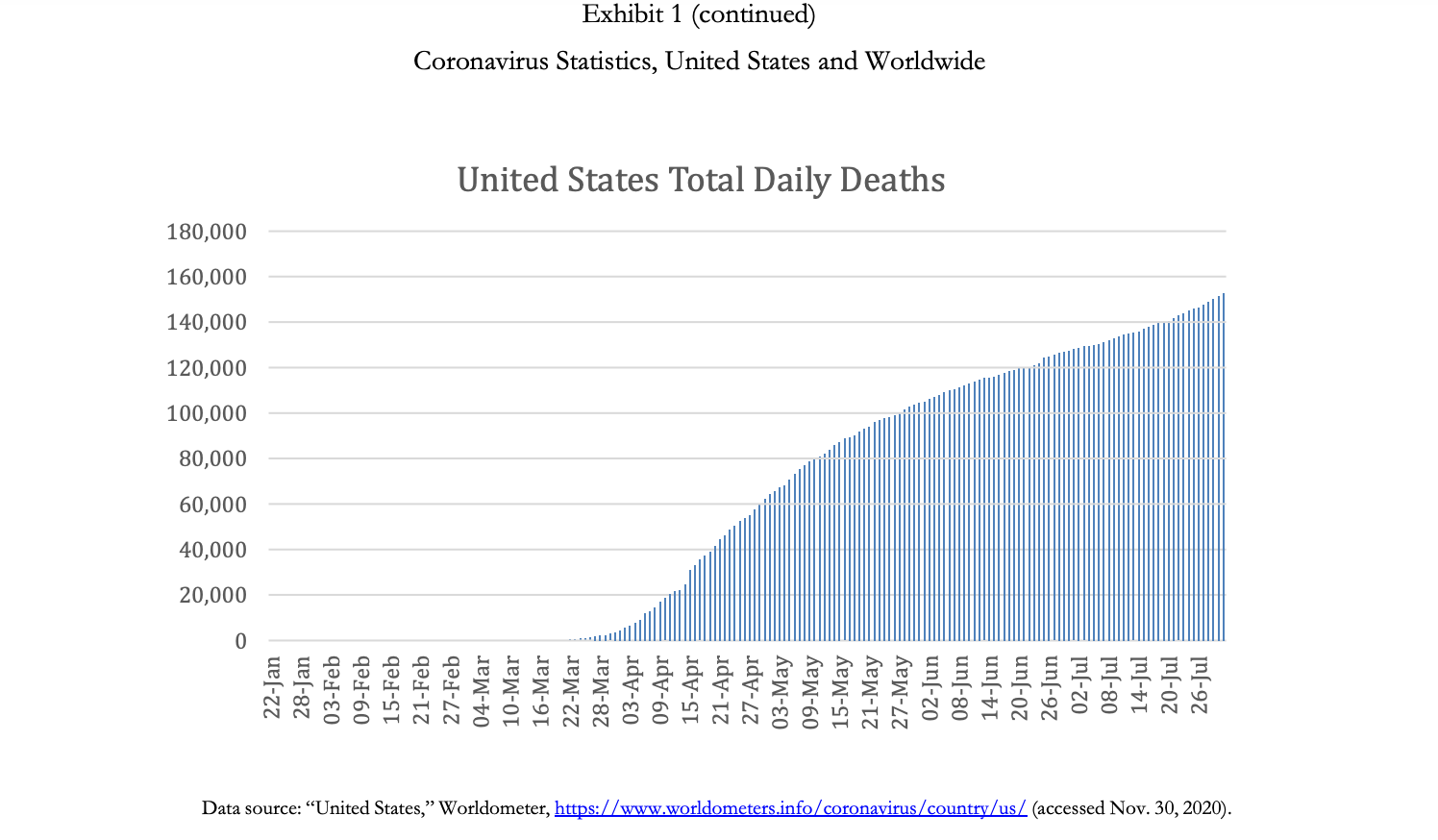

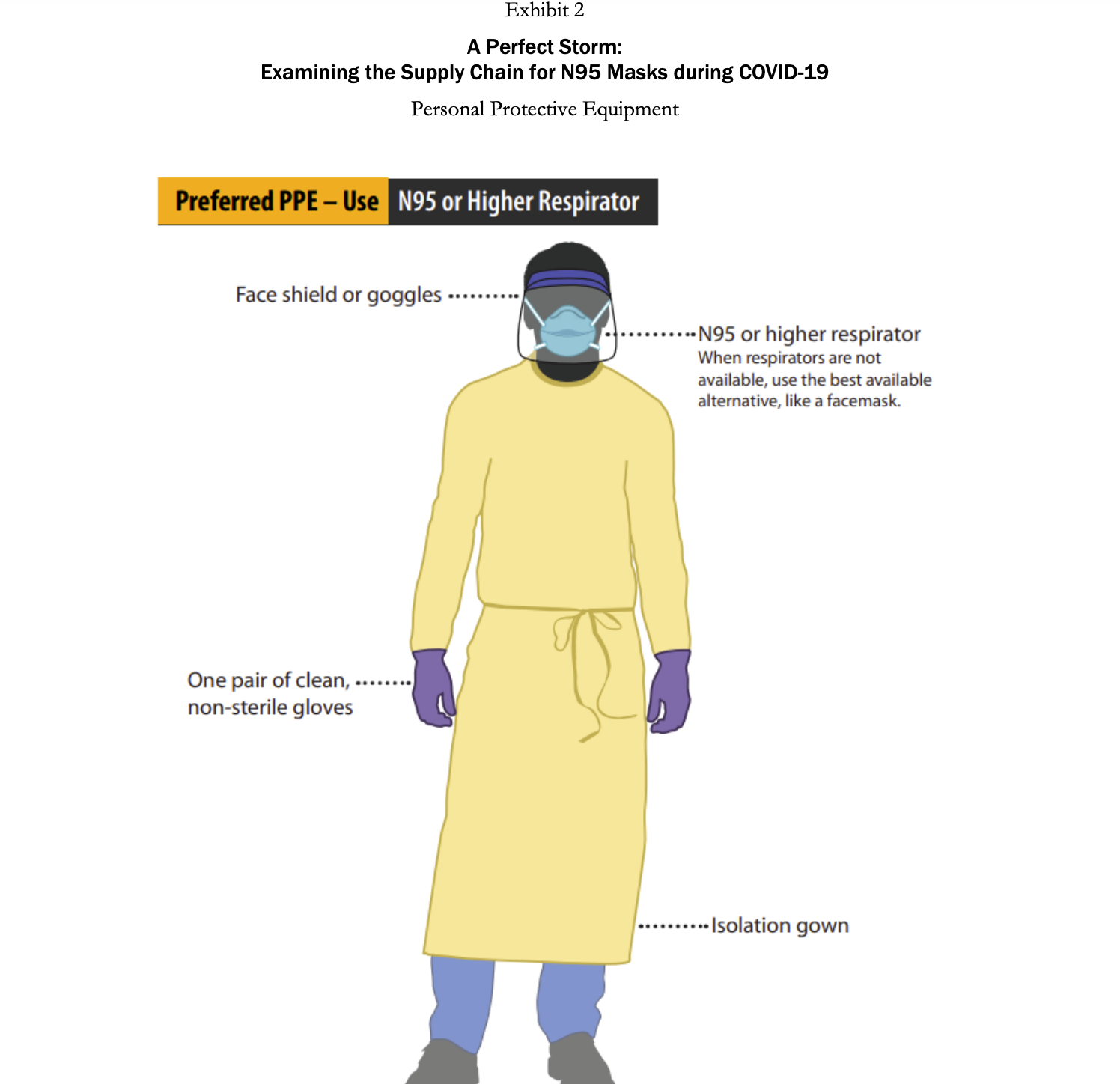

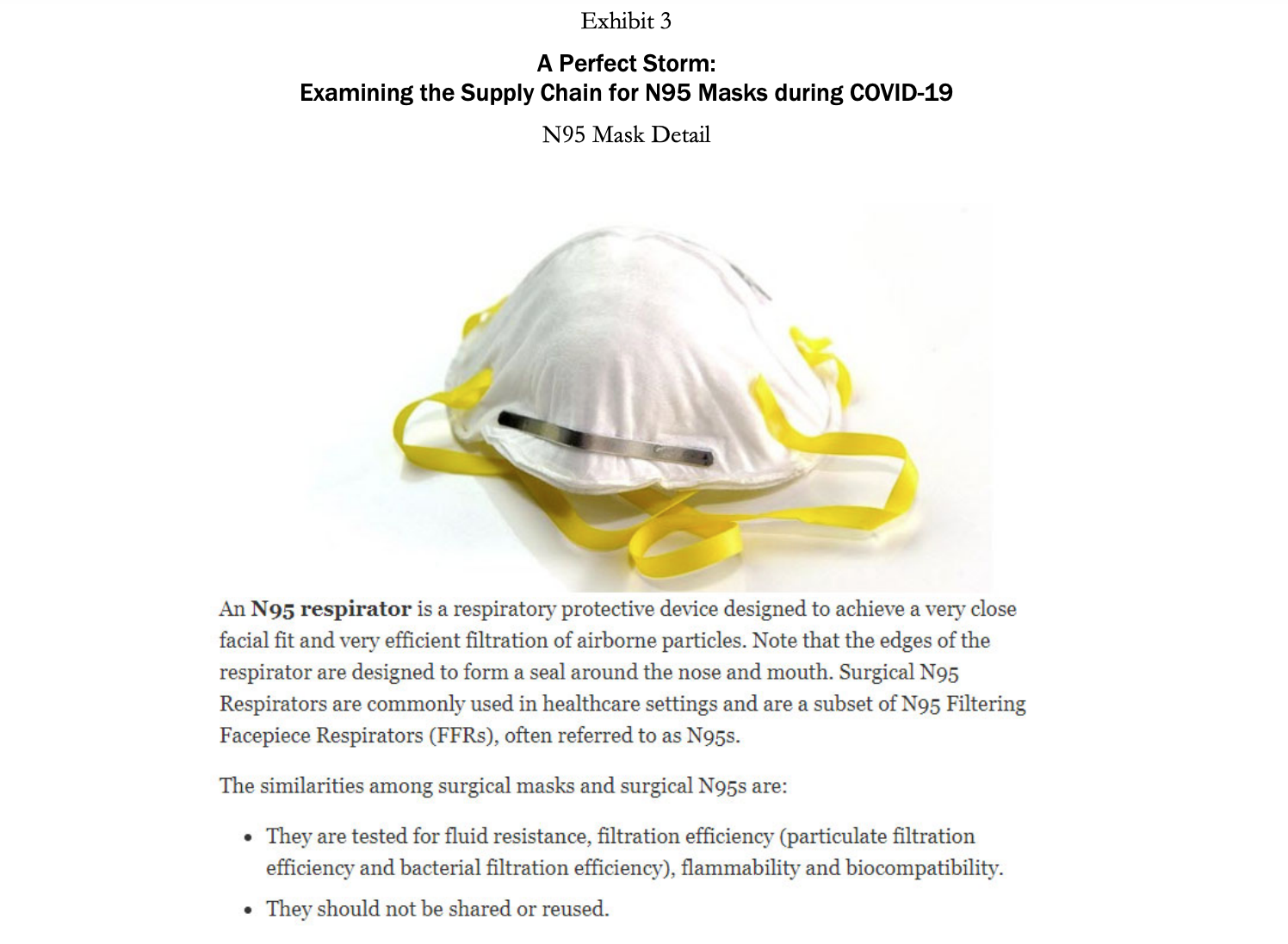

A Perfect Storm: Examining the Supply Chain for N95 Masks during COVID-19 Demand is such that people are placing orders with everyone-tough to know how much of the forecast is real demand. We get orders from all the hospitals, but they are placing orders with multiple distributorsso we'll tell them we have a product, and then they'll say they got it from someone else! The market is nuts. -Anonymous VP of sourcing at a multinational health care services company Introduction Coronavirus was a flu disease similar to the one that ravaged populations during the H1N1 pandemic in 2009. It affected the respiratory tract of a person's body and caused difficulties in breathing. It was contagious and spread through droplets of saliva and discharges from the nose. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was a new strain of coronavirus that had not previously been identified in humans. Most people infected with the COVID-19 virus who were symptomatic experienced mild to moderate respiratory illness, fever, and fatigue and recovered without needing to be hospitalized. However, there were cases wherein people were asymptomatic (i.e., did not show any symptoms) but still tested positive for the virus, complicating attempts to stop its spread. Furthermore, since it mainly affected the respiratory tract, COVID-19 could cause difficulty in breathing and result in pneumonia. Therefore, people of any age with underlying medical conditionssuch as cardiovascular or chronic respiratory disease, diabetes, and cancer-and older patients were more likely to develop serious illness from COVID-19.2 The first COVID-19 case in a human patient was detected in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. In the United States, the first case was detected on January 22, in Washington State. By February 2020, the adverse effects of the virus led many countries to shut down and to implement stay-at-home orders and travel restrictions. In March 2020, disruptions to global supply chains began to occur as both developed and developing countries instituted bans on exports of materials like medical supplies, food, and toilet paper. In that same month, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 crisis a global pandemic. By August 2020, almost every country in the world had been affected by the virus, with over 15.6 million people Page 2 UV8175 infected globally, resulting in over half a million deaths due to the virus. In the United States, by July 2020, over 4.1 million people had been infected with the virus and more than 150,000 deaths had occurred (Exhibit 1).4 The COVID-19 outbreak was unprecedented in its scale and severity, impacting the health of entire countries as well as economies across the world. Because China was the epicenter of the pandemic, the impact of COVID-19 on global supply chains was extensive. Manufacturers incurred production stoppages in locations across China and the world, and there was a shortage of raw materials, subassemblies, and finished goods. 5 As a result, there were empty market shelves and shortages of essential supplies caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Masks were critical tools in the fight to stop the spread of the virus. There were different types of masks available, such as surgical masks, respirators (N95 masks), and cloth masks. Herein, we highlight the importance of N95 masks in fighting the virus and illustrate the effect COVID-19 had on the supply of N95 masks during the pandemic. Technical Details of the N95 Mask COVID-19 was an extremely contagious disease that spread easily through the transmission of infectious droplets from person to person. Some of the most effective ways to contain the virus were to maintain social distancing, practice cleanliness by continually washing hands, and wear masks and gloves. For health care personnel who treated infected patients and were in close proximity to the virus, this required wearing personal protective equipment (PPE). PPE (Exhibit 2) included face shields, protective garments, mouth-and-nose- protection equipment, gloves, visors, and goggles. Face shields included face-covering plastic shields and different types of masks. Multiple masks were available, including cloth masks, medical-grade masks, and respirators. Cloth masks were not FDA approved, but reduced the likelihood of transmitting the virus by containing the number of respiratory droplets a person expelled. Medical-grade masks and respirators were FDA approved and created an effective barrier against large droplets and splashes of hazardous fluids. Because of this, medical-grade masks and respirators were the preferred masks worn by health care personnel.7 In the United States, medical-grade surgical respirators were approved by both the FDA and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).8 N95 respirators were specialized masks that filtered out at least 95% of particles above 0.3 microns (see Exhibit 3). There were also N99 and N100 respirators (e.g., N100s stop at least 99.97% of particles from entering). N95 respirators worked by filtering out hazardous particles as thin as three-tenths of a micron through the complex structure of nonwoven material and the dense network of the materials' fibers. The hazardous particles got trapped in the complex structure. Masks also had electrostatically charged material to attract and filter out hazardous particles. As hazardous particles built up, masks became a more efficient filter. However, the buildup also made the mask more difficult to breathe through, which was why the masks and filters were made to be disposable. A medical N95 respirator was typically made from polypropylene and consisted of multiple layers of nonwoven fabric. The protective layers of fabric that cover the inside and outside of the mask were created using spun bonding. Between the spun-bond layers, there was a pre-filtration layer, and then the filtration layer. The pre-filtration layer could be molded to form the desired shape of the mask and remain in that shape because the pre-filtration layer was usually needle-woven, which made it thicker and stiffer. The filtration efficiency was determined by the last layer, which was a high-efficiency, melt-blown, nonwoven material. However, sometimes melt-blown fabric was also thermally bonded to add strength and abrasion resistance. The full respirators were made through converting machinery, which combines the layers through ultrasonic welding and adds straps and metal strips to adjust the mask over the user's nose. The respirators were then sterilized as a last shipment.10 Supply Issues step before PPE, including N95 respirators, played an integral part in the fight against the pandemic. China was a major exporter of PPE, accounting for 43% of global exports in 2018. For the United States, China produced a large number of the products needed to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2018, China accounted for 48% of the PPE on the US market. 11 The epicenter of the COVID-19 virus was Wuhan, China. In December 2019 and January 2020, as the number of cases in China increased rapidly, the Chinese government worked to import N95 masks. China managed to import 56 million respirators and masks from other countries by the first week of January. On January 30 alone, China managed to import 20 million respirators and surgical masks in 24 hours.12 In February, as conditions worsened, China imposed travel restrictions and factories were shut down. As a result, exports of masks to the United States declined by nearly 20%.13 Furthermore, other global manufacturers that produced masks saw their capacities reduce due to shutdowns, social distancing, and travel restrictions. This resulted in a reduction in the global supply of masks, just as the demand for these much-needed items surged as more than 50 countries around the world faced the same dire situation as the United States. Countries began to stockpile supplies, and even passed laws (e.g., in Italy and Spain) on restricting exports of these much-needed items. N95 masks had been manufactured for decades. However, in the United States, manufacturers struggled to ramp up mask production during the pandemic. Multiple factors contributed to this. First, even before the pandemic, mask-making companies 14 in the United States typically ran at high capacity (around 95%).15 This was because the equipment needed to make these materials was very costly, and thus it was in a manufacturer's best interest to ensure high utilizations. As a result, when the pandemic hit, it was difficult for manufacturers to increase their capacity. Further complicating this issue was the fact that procuring new equipment would be costly, and was viewed as risky in potentially uncertain economic times. In countries such as Taiwan, the government provided subsidized loans to mask manufacturers and offered incentives that if they produced a certain number of masks, the government would forgo the loan or buy a previously agreed-upon quantity of masks to minimize the manufacturers' investment risk. In the United States, the government did not offer similar incentives to manufacturers or provide any subsidized loans, further slowing the scaling-up process for mask production.16 Second, there was a lack of dependable data among the hospitals, manufacturers, and distributors. Specifically, there was not a centralized information platform or IT infrastructure among the hospitals, manufacturers, and suppliers such that demand needs could be shared easily with each party. It even proved difficult for manufacturers to identify alternate sources of supply. For instance, a manufacturer might have respirators available, but those might sit idle in a facility because the manufacturer was unable to procure the elastics that hold the mask on the face. 17 There were some localized data hubs available among the hospitals, manufacturers, and distributors, but these hubs were often very confusing, and no one took the initiative to provide reliable data. In general, there was no transparency or visibility of data for officials to look at and make decisions based on. Nonprofits such as Helena and Textile Connect attempted to help improve the sharing of information between entities. 18 For example, Helena managed to connect medical professionals and health care facilities in need of masks with over 13 million masks (N95, surgical, cloth) by the end of July.19 Finally, there were supply disruptions caused by COVID-19. A key challenge was that a critical component for high-quality masks, nonwoven polypropylene, remained in short supply.20 Because of the above factors, mask producers in the United States could not supply enough masks to meet demand. By July of 2020, the United States still manufactured only 30% of the masks used domestically and imported the remaining 70%. To put the production of masks in the United States into perspective, 3M was one of the largest mask producers in the United States. 3M's facilities could supply 55 million masks per month. 21 Taiwan, a leading producer of masks, was capable of producing 364 million masks per month.22 By June 2020, approximately 40% of facilities still had not obtained N95 masks and were lacking proper protection, which not only put hospital personnel at risk of getting sick, but also reduced the capacity of hospitals to test and care for sick patients. Many hospital personnel were still operating in a hazardous manner, with staffing shortages and personnel using either no masks or makeshift masks. 23 Of the 13,696 nursing facilities reporting to the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN), 16% of the facilities did not have enough N95 mask supplies for the next seven days. Furthermore, 80% of the reporting facilities either were reusing or extending the use of N95 masks. By July of 2020, seven months since the virus was first detected, the volume of masks imported into the United States had gone up, but many of these shipments did not meet the required standards and were not certified by the NIOSH or the FDA. Adding to the difficulty, a large number of non-FDA-approved masks had also entered the market through online sales and brokers, leading to further confusion in the marketplace. For example, a hospital in the United Kingdom desperate for masks, ordered 400,000 masks from a supplier. However, the supplier turned out not to be a manufacturer, but instead, simply a middleman broker. The broker was only able to supply 6,000 masks, of which only 2,500 passed standards. 24 Stories such as this were common throughout the initial months of the pandemic. US Strategic National Stockpile Supply issues also occurred with the US government's Strategic National Stockpile, which was meant to support states and local governments with medical supplies and lifesaving care units during health emergencies. Different types of disasters such as hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, pandemics, or terrorist threats required the Strategic National Stockpile to be stocked with different types of equipment. The officials in charge of the stockpile had to decide which of these different kinds of threats to plan for. The measures that officials had previously taken between 2005 and 2008 in response to the 2009 swine-flu pandemic were seen as a success, therefore officials were less worried about the threat of a pandemic. 25 As a result, they stocked fewer basic medical supplies, like masks, that would have proven useful during an infectious-disease outbreak such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, the Strategic National Stockpile focused its support on bioterrorism threats such as anthrax, and on sudden mass-casualty events like 9/11. Officials believed that the Strategic National Stockpile should have bioweapon antidotes and other drugs that were not easily available on store shelves, rather than common items one could buy at drugstores, such as respirators and other PPE equipment. As stated by Greg Burell, director of the Strategic National Stockpile, in a 2020 interview, "The Strategic National Stockpile was built to respond primarily to chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear events, whether by a terrorist, or a state actor, or something that might happen along those same lines that was accidental."26 In March 2020, the US Strategic National Stockpile contained only about 12 million N95 masks, as compared to the 3.5 billion N95 masks that federal officials estimated the health care system would need to fight the pandemic. Officials who monitored the Strategic National Stockpile were hopeful that hospitals were making their own stockpiles to handle the crisis, and then only when the hospitals ran out of supplies would the hospitals fall back on the Strategic National Stockpile. But hospitals' inventory-management procedures did not align with this strategy. Rather than keeping their own stockpiles, hospitals had what's called just in time stock, in which supplies were delivered right as they were needed. At most, there was one week's inventory in most hospitals of the necessary PPE supplies, which was not enough to last a global pandemic. 27 Hospitals were vulnerable to the supply issues discussed above, and a domino effect" occurred wherein issues overlapped and exacerbated one another. Demand Issues Supply shortages were not the only issue government officials, health care providers, and manufacturers were running into with respect to masks. The incredible surge in demand for masks was also an issue. One of the main reasons for the spike in mask use and rising panic in hospitals in early 2020 was because hospitals and health care agencies were not ready for the vast testing requirements needed for COVID-19. As a result, this increased the number of patients under investigation. Simultaneously, the test results took 7 to 10 days to come back. Therefore, patients suspected of having COVID-19 were treated as if they had the virus. This resulted in a hospital using six times the PPE it would have normally used if it had known which patients actually had the virus. At the same time, consumers started to panic-buy the N95 masks and the demand for masks increased considerably. This limited the supply of masks for health care workers, for whom the masks were designed and who needed them the most.28 In April 2020, the number of cases in the United States began to increase exponentially, and the risk of contracting the virus became higher for health care workers. Due to the shortages in supply, officials asked health care workers to use looser surgical masks rather than medical-grade N95 respirators, a request that raised alarms among doctors and nurses who would be less protected when treating the patients. 29 Besides putting the workers in danger, this also could lead to an increased spreading of the virus among patients and other health care workers. Emerging problems over the quality and quantity of protective gear was the latest challenge in the United States as the number of infected people was growing rapidly. Medical staff reused equipment, cleaned it with unproven methods, and used substandard material in the absence of adequate supplies. All of this went against well-established practices for infection control and heightened the risk of further spreading the virus. Non-COVID-19-related cases such as cancer treatments and organ transplants were being deemed "nonessential" for the time being. Due to shortages in PPE equipment, treatments for non-COVID-19-related cases were postponed or rescheduled to conserve PPE this not only handicapped medical facilities and staff, but also contributed to additional stress for both patients and their families.30 The US private sector faced a number of challenges posed by the COVID-19 virus. As the need for medical care for patients across the country increased, the demand for protective N95 disposable respirators skyrocketed. To help the government, large multinational companies began to shift resources toward producing PPE. For example, Honeywell increased its production of N95 masks across all its factories by hiring 500 new employees. Clothing manufacturer Hanesbrands Inc. halted its general apparel production to create FDA- approved cotton masks for the general public to wear as a protective measure. Apple sourced over 20 million masks through its supply chain for health professionals across the United States and Europe to help with more immediate needs. To meet the demand of local hospitals, many small companies and businesses jumped in to help. For example, AST Sportswear repurposed its production to produce cotton masks. Similarly, MyPillow, from Minnesota, shifted production from pillows to cotton masks and dedicated 90% of its staff to the effort.31 Universities also helped their local hospitals by providing them with N95 masks. For example, Textile Colleges in the University of North Carolina system, in collaboration with such industry partners as Exxon and Nature Works, produced five million masks a week. 32 President Donald Trump also invoked the Defense Production Act, which required major manufacturers to prioritize contracts and to allocate production lines to produce important products needed to fight COVID-19.33 Conclusion COVID-19 was an unprecedented pandemic that impacted nations across the globe. It caused disruptions throughout industries, and it suffocated global supply chains to such an extent that it resulted in a scarcity in supplies much needed for hospitals. The level of panic created by the COVID-19 pandemic led to confusion and misinformation. Multiple waves of the pandemic caused mass debate and conflict in countries such as the United States. This raises a number of after-the-fact questions regarding what could have been done differently to better manage the pandemic. What actions would have helped prevent shortages of much-needed supplies such as PPE and masks? Debates will persist as to whether our supply chains and Strategic National Stockpile failed us. And while people continued to learn from mistakes made during the pandemic, going forward, the question remained: How to prepare for future pandemics? 700,000 600,000 500,000 400,000 300,000 200,000 100,000 0 31-Dec Exhibit 1 A Perfect Storm: Examining the Supply Chain for N95 Masks during COVID-19 Coronavirus S, United States and Worldwide 31-Jan Global Daily New Cases 28-Feb 31-Mar 30-Apr 31-May 30-Jun Data source: "Reported Cases and Deaths by Country, Territory, or Conveyance," https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#countries (accessed Nov. 30, 2020). United States Daily New Cases 80,000 70,000 60,000 50,000 40,000 30,000 20,000 10,000 31-Jul Worldometer, 140,000 120,000 100,000 80,000 60,000 40,000 20,000 0 22-Jan 28-Jan 03-Feb 09-Feb 15-Feb 21-Feb 27-Feb 04-Mar 10-Mar 16-Mar 22-Mar 22-Mar 29 Mor 28-Mar 03-Apr 03-Apr 09-Apr 09-Apr 180,000 160,000 United States Total Daily Deaths 15-Apr 21-Apr 27-Apr 03-May PIA-SO 09-May Data source: "United States," Worldometer, https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/us/ (accessed Nov. 30, 2020). 09-May 15-May 21-May 27-May 02-Jun 08-Jun 14-Jun 20-Jun 26-Jun 02-Jul [n[-80 14-Jul 20-Jul 26-Jul Exhibit 1 (continued) Coronavirus Statistics, United States and Worldwide Exhibit 2 A Perfect Storm: Examining the Supply Chain for N95 Masks during COVID-19 Personal Protective Equipment Preferred PPE - Use N95 or Higher Respirator Face shield or goggles One pair of clean, non-sterile gloves --N95 or higher respirator When respirators are not available, use the best available alternative, like a facemask. ..... Isolation gown Exhibit 3 A Perfect Storm: Examining the Supply Chain for N95 Masks during COVID-19 N95 Mask Detail An N95 respirator is a respiratory protective device designed to achieve a very close facial fit and very efficient filtration of airborne particles. Note that the edges of the respirator are designed to form a seal around the nose and mouth. Surgical N95 Respirators are commonly used in healthcare settings and are a subset of N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirators (FFRS), often referred to as N95s. The similarities among surgical masks and surgical N95s are: They are tested for fluid resistance, filtration efficiency (particulate filtration efficiency and bacterial filtration efficiency), flammability and biocompatibility. They should not be shared or reused.

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started