Accounting Problem I have been stuck on for days please help, and no it is not incomplete, the questions are 1-8. part 1

part 1

part 2

part 2

part 3

part 3

part 4

part 4

Lastly part 5

Lastly part 5

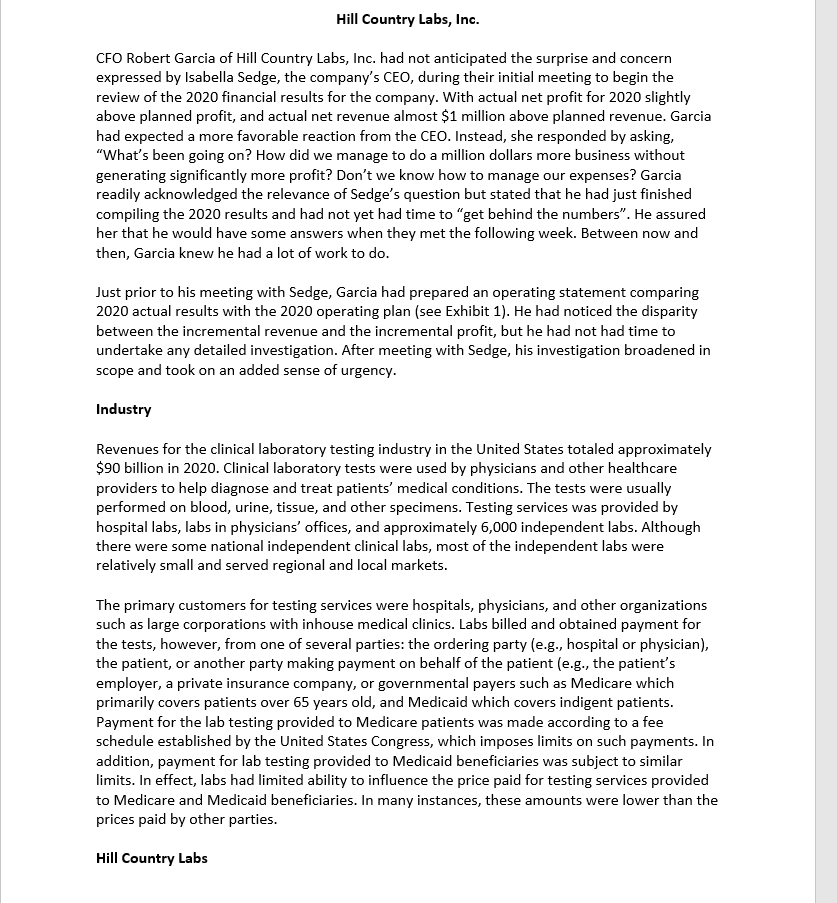

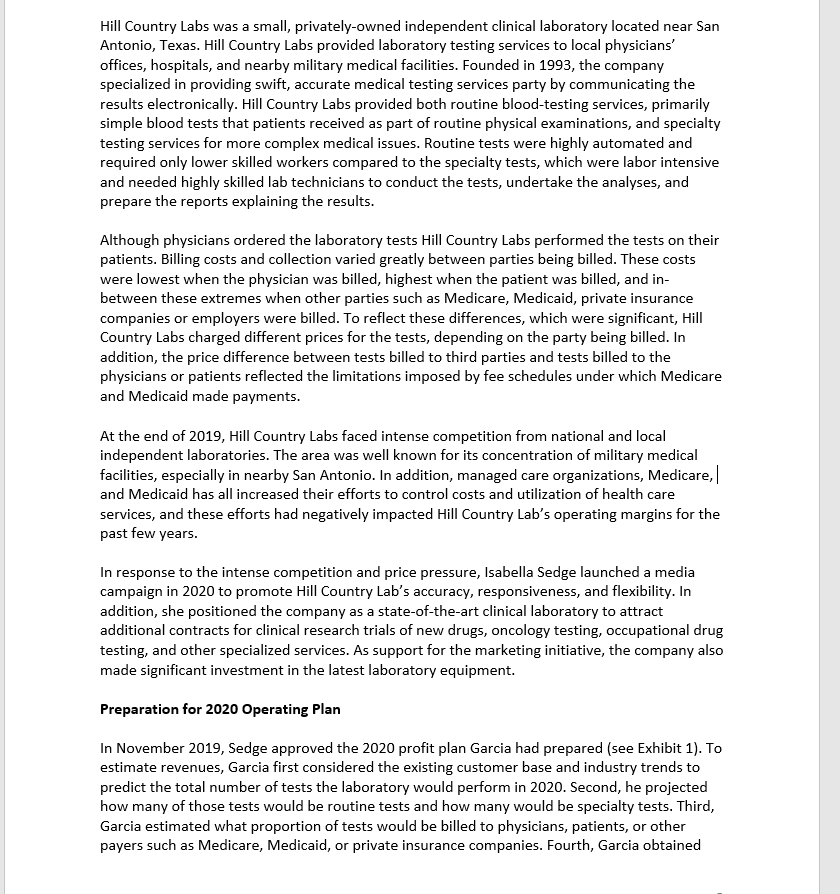

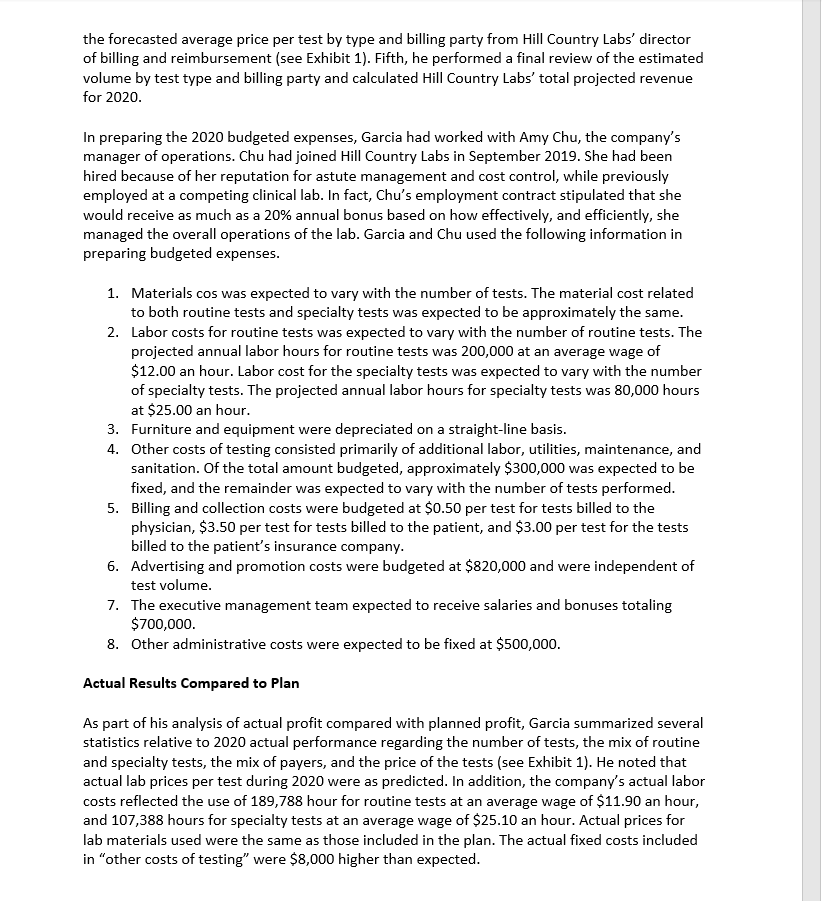

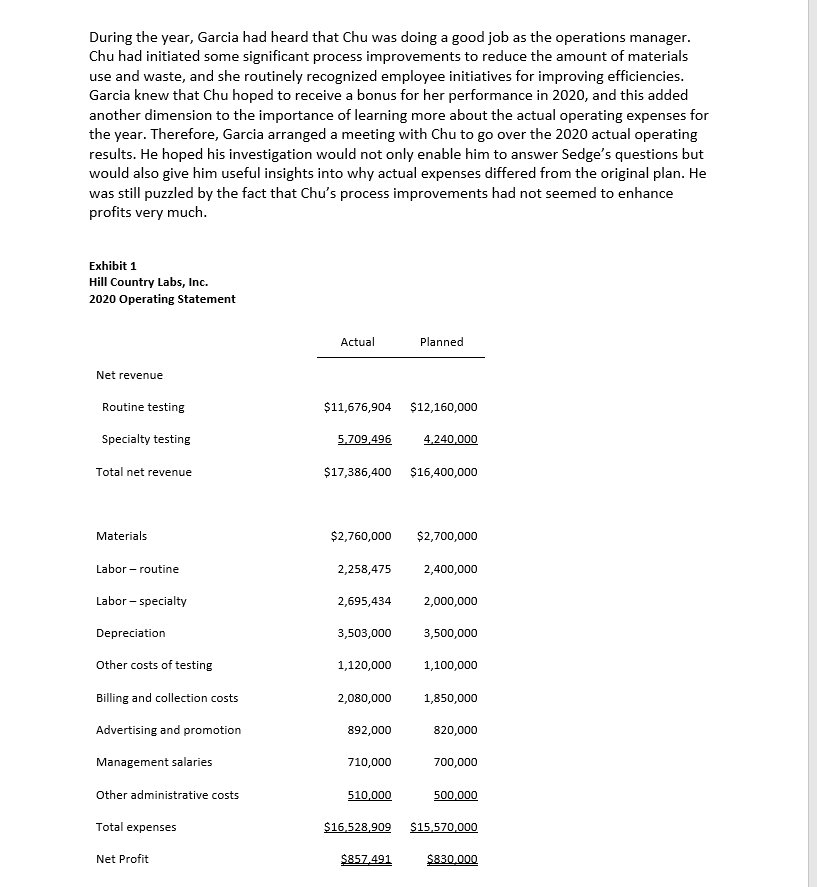

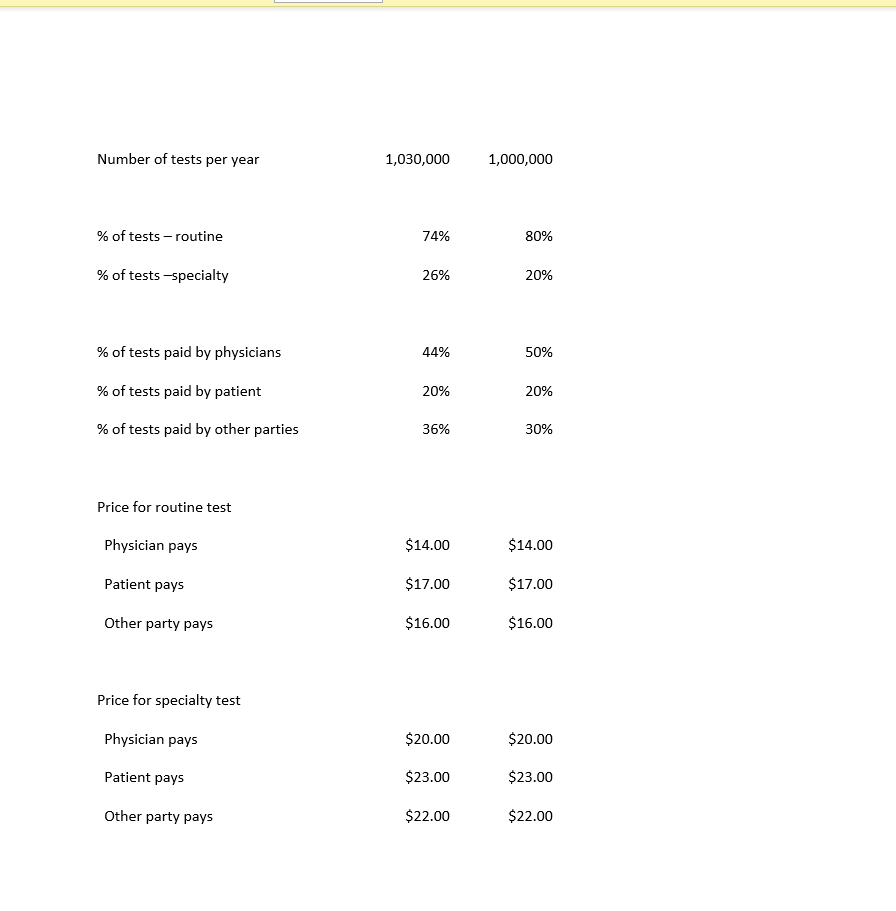

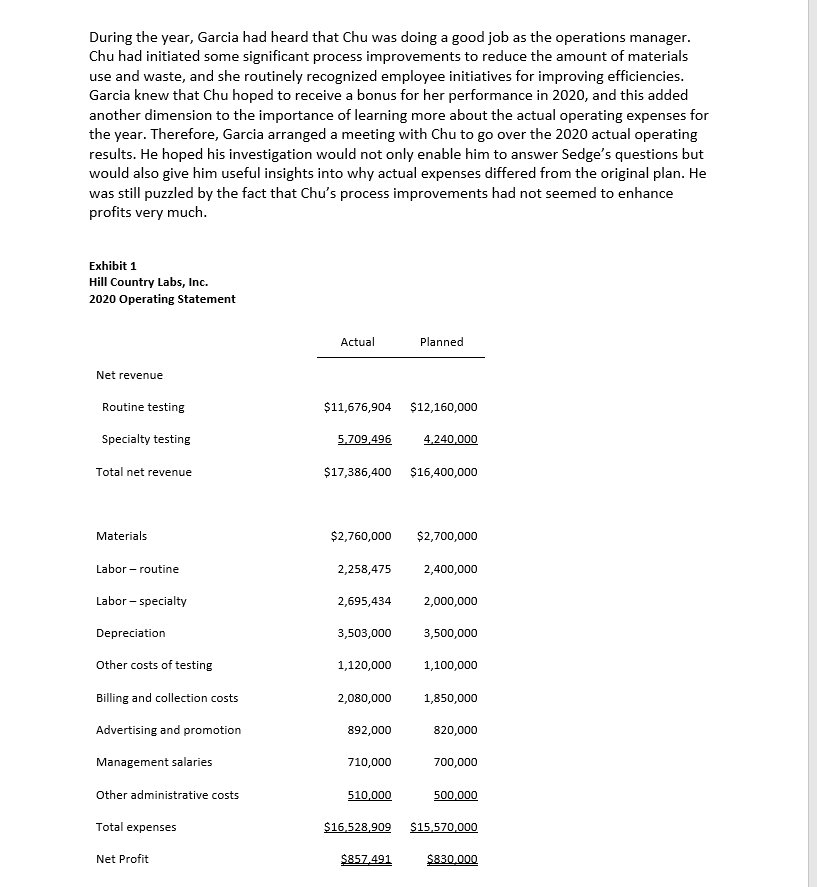

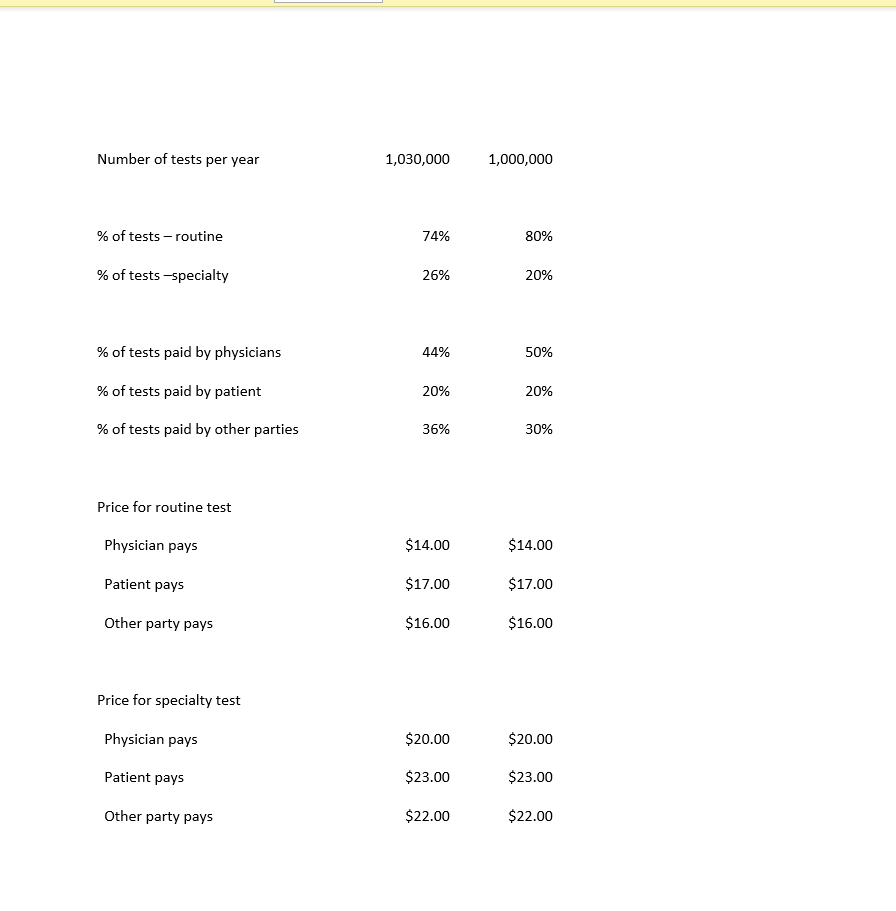

Hill Country Labs, Inc. CFO Robert Garcia of Hill Country Labs, Inc. had not anticipated the surprise and concern expressed by Isabella Sedge, the company's CEO, during their initial meeting to begin the review of the 2020 financial results for the company. With actual net profit for 2020 slightly above planned profit, and actual net revenue almost $1 million above planned revenue. Garcia had expected a more favorable reaction from the CEO. Instead, she responded by asking, "What's been going on? How did we manage to do a million dollars more business without generating significantly more profit? Don't we know how to manage our expenses? Garcia readily acknowledged the relevance of Sedge's question but stated that he had just finished compiling the 2020 results and had not yet had time to "get behind the numbers". He assured her that he would have some answers when they met the following week. Between now and then, Garcia knew he had a lot of work to do. Just prior to his meeting with Sedge, Garcia had prepared an operating statement comparing 2020 actual results with the 2020 operating plan (see Exhibit 1). He had noticed the disparity between the incremental revenue and the incremental profit, but he had not had time to undertake any detailed investigation. After meeting with Sedge, his investigation broadened in scope and took on an added sense of urgency. Industry Revenues for the clinical laboratory testing industry in the United States totaled approximately $90 billion in 2020. Clinical laboratory tests were used by physicians and other healthcare providers to help diagnose and treat patients' medical conditions. The tests were usually performed on blood, urine, tissue, and other specimens. Testing services was provided by hospital labs, labs in physicians' offices, and approximately 6,000 independent labs. Although there were some national independent clinical labs, most of the independent labs were relatively small and served regional and local markets. The primary customers for testing services were hospitals, physicians, and other organizations such as large corporations with inhouse medical clinics. Labs billed and obtained payment for the tests, however, from one of several parties: the ordering party (e.g., hospital or physician), the patient, or another party making payment on behalf of the patient (e.g., the patient's employer, a private insurance company, or governmental payers such as Medicare which primarily covers patients over 65 years old, and Medicaid which covers indigent patients. Payment for the lab testing provided to Medicare patients was made according to a fee schedule established by the United States Congress, which imposes limits on such payments. In addition, payment for lab testing provided to Medicaid beneficiaries was subject to similar limits. In effect, labs had limited ability to influence the price paid for testing services provided to Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. In many instances, these amounts were lower than the prices paid by other parties. Hill Country Labs Hill Country Labs was a small, privately-owned independent clinical laboratory located near San Antonio, Texas. Hill Country Labs provided laboratory testing services to local physicians' offices, hospitals, and nearby military medical facilities. Founded in 1993, the company specialized in providing swift, accurate medical testing services party by communicating the results electronically. Hill Country Labs provided both routine blood-testing services, primarily simple blood tests that patients received as part of routine physical examinations, and specialty testing services for more complex medical issues. Routine tests were highly automated and required only lower skilled workers compared to the specialty tests, which were labor intensive and needed highly skilled lab technicians to conduct the tests, undertake the analyses, and prepare the reports explaining the results. Although physicians ordered the laboratory tests Hill Country Labs performed the tests on their patients. Billing costs and collection varied greatly between parties being billed. These costs were lowest when the physician was billed, highest when the patient was billed, and in- between these extremes when other parties such as Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance companies or employers were billed. To reflect these differences, which were significant, Hill Country Labs charged different prices for the tests, depending on the party being billed. In addition, the price difference between tests billed to third parties and tests billed to the physicians or patients reflected the limitations imposed by fee schedules under which Medicare and Medicaid made payments. At the end of 2019, Hill Country Labs faced intense competition from national and local independent laboratories. The area was well known for its concentration of military medical facilities, especially in nearby San Antonio. In addition, managed care organizations, Medicare, || and Medicaid has all increased their efforts to control costs and utilization of health care services, and these efforts had negatively impacted Hill Country Lab's operating margins for the past few years. In response to the intense competition and price pressure, Isabella Sedge launched a media campaign in 2020 to promote Hill Country Lab's accuracy, responsiveness, and flexibility. In addition, she positioned the company as a state-of-the-art clinical laboratory to attract additional contracts for clinical research trials of new drugs, oncology testing, occupational drug testing, and other specialized services. As support for the marketing initiative, the company also made significant investment in the latest laboratory equipment. Preparation for 2020 Operating Plan In November 2019, Sedge approved the 2020 profit plan Garcia had prepared (see Exhibit 1). To estimate revenues, Garcia first considered the existing customer base and industry trends to predict the total number of tests the laboratory would perform in 2020. Second, he projected how many of those tests would be routine tests and how many would be specialty tests. Third, Garcia estimated what proportion of tests would be billed to physicians, patients, or other payers such as Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance companies. Fourth, Garcia obtained the forecasted average price per test by type and billing party from Hill Country Labs' director of billing and reimbursement (see Exhibit 1). Fifth, he performed a final review of the estimated volume by test type and billing party and calculated Hill Country Labs' total projected revenue for 2020. In preparing the 2020 budgeted expenses, Garcia had worked with Amy Chu, the company's manager of operations. Chu had joined Hill Country Labs in September 2019. She had been hired because of her reputation for astute management and cost control, while previously employed at a competing clinical lab. In fact, Chu's employment contract stipulated that she would receive as much as a 20% annual bonus based on how effectively, and efficiently, she managed the overall operations of the lab. Garcia and Chu used the following information in preparing budgeted expenses. 1. Materials cos was expected to vary with the number of tests. The material cost related to both routine tests and specialty tests was expected to be approximately the same. 2. Labor costs for routine tests was expected to vary with the number of routine tests. The projected annual labor hours for routine tests was 200,000 at an average wage of $12.00 an hour. Labor cost for the specialty tests was expected to vary with the number of specialty tests. The projected annual labor hours for specialty tests was 80,000 hours at $25.00 an hour. 3. Furniture and equipment were depreciated on a straight-line basis. 4. Other costs of testing consisted primarily of additional labor, utilities, maintenance, and sanitation. Of the total amount budgeted, approximately $300,000 was expected to be fixed, and the remainder was expected to vary with the number of tests performed. 5. Billing and collection costs were budgeted at $0.50 per test for tests billed to the physician, $3.50 per test for tests billed to the patient, and $3.00 per test for the tests billed to the patient's insurance company. 6. Advertising and promotion costs were budgeted at $820,000 and were independent of test volume. 7. The executive management team expected to receive salaries and bonuses totaling $700,000. 8. Other administrative costs were expected to be fixed at $500,000. Actual Results Compared to Plan As part of his analysis of actual profit compared with planned profit, Garcia summarized several statistics relative to 2020 actual performance regarding the number of tests, the mix of routine and specialty tests, the mix of payers, and the price of the tests (see Exhibit 1). He noted that actual lab prices per test during 2020 were as predicted. In addition, the company's actual labor costs reflected the use of 189,788 hour for routine tests at an average wage of $11.90 an hour, and 107,388 hours for specialty tests at an average wage of $25.10 an hour. Actual prices for lab materials used were the same as those included in the plan. The actual fixed costs included in "other costs of testing" were $8,000 higher than expected. During the year, Garcia had heard that Chu was doing a good job as the operations manager. Chu had initiated some significant process improvements to reduce the amount of materials use and waste, and she routinely recognized employee initiatives for improving efficiencies. Garcia knew that Chu hoped to receive a bonus for her performance in 2020, and this added another dimension to the importance of learning more about the actual operating expenses for the year. Therefore, Garcia arranged a meeting with Chu to go over the 2020 actual operating results. He hoped his investigation would not only enable him to answer Sedge's questions but would also give him useful insights into why actual expenses differed from the original plan. He was still puzzled by the fact that Chu's process improvements had not seemed to enhance profits very much. Exhibit 1 Hill Country Labs, Inc. 2020 Operating Statement Actual Planned Net revenue Routine testing $11,676,904 $12,160,000 Specialty testing 5,709,496 4,240,000 Total net revenue $17,386,400 $16,400,000 Materials $2,760,000 $2,700,000 Labor-routine 2,258,475 2,400,000 Labor - specialty 2,695,434 2,000,000 Depreciation 3,503,000 3,500,000 Other costs of testing 1,120,000 1,100,000 Billing and collection costs 2,080,000 1,850,000 Advertising and promotion 892,000 820,000 Management salaries 710,000 700,000 Other administrative costs 510,000 500,000 Total expenses $16.528,909 $15.570,000 Net Profit $857.491 $830.000 Number of tests per year 1,030,000 1,000,000 % of tests - routine 74% 80% % of tests-specialty 26% 20% % of tests paid by physicians 44% 50% % of tests paid by patient 20% 20% % of tests paid by other parties 36% 30% Price for routine test Physician pays $14.00 $14.00 Patient pays $17.00 $17.00 Other party pays $16.00 $16.00 Price for specialty test Physician pays $20.00 $20.00 Patient pays $23.00 $23.00 Other party pays $22.00 $22.00 Hill Country Labs, Inc. CFO Robert Garcia of Hill Country Labs, Inc. had not anticipated the surprise and concern expressed by Isabella Sedge, the company's CEO, during their initial meeting to begin the review of the 2020 financial results for the company. With actual net profit for 2020 slightly above planned profit, and actual net revenue almost $1 million above planned revenue. Garcia had expected a more favorable reaction from the CEO. Instead, she responded by asking, "What's been going on? How did we manage to do a million dollars more business without generating significantly more profit? Don't we know how to manage our expenses? Garcia readily acknowledged the relevance of Sedge's question but stated that he had just finished compiling the 2020 results and had not yet had time to "get behind the numbers". He assured her that he would have some answers when they met the following week. Between now and then, Garcia knew he had a lot of work to do. Just prior to his meeting with Sedge, Garcia had prepared an operating statement comparing 2020 actual results with the 2020 operating plan (see Exhibit 1). He had noticed the disparity between the incremental revenue and the incremental profit, but he had not had time to undertake any detailed investigation. After meeting with Sedge, his investigation broadened in scope and took on an added sense of urgency. Industry Revenues for the clinical laboratory testing industry in the United States totaled approximately $90 billion in 2020. Clinical laboratory tests were used by physicians and other healthcare providers to help diagnose and treat patients' medical conditions. The tests were usually performed on blood, urine, tissue, and other specimens. Testing services was provided by hospital labs, labs in physicians' offices, and approximately 6,000 independent labs. Although there were some national independent clinical labs, most of the independent labs were relatively small and served regional and local markets. The primary customers for testing services were hospitals, physicians, and other organizations such as large corporations with inhouse medical clinics. Labs billed and obtained payment for the tests, however, from one of several parties: the ordering party (e.g., hospital or physician), the patient, or another party making payment on behalf of the patient (e.g., the patient's employer, a private insurance company, or governmental payers such as Medicare which primarily covers patients over 65 years old, and Medicaid which covers indigent patients. Payment for the lab testing provided to Medicare patients was made according to a fee schedule established by the United States Congress, which imposes limits on such payments. In addition, payment for lab testing provided to Medicaid beneficiaries was subject to similar limits. In effect, labs had limited ability to influence the price paid for testing services provided to Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. In many instances, these amounts were lower than the prices paid by other parties. Hill Country Labs Hill Country Labs was a small, privately-owned independent clinical laboratory located near San Antonio, Texas. Hill Country Labs provided laboratory testing services to local physicians' offices, hospitals, and nearby military medical facilities. Founded in 1993, the company specialized in providing swift, accurate medical testing services party by communicating the results electronically. Hill Country Labs provided both routine blood-testing services, primarily simple blood tests that patients received as part of routine physical examinations, and specialty testing services for more complex medical issues. Routine tests were highly automated and required only lower skilled workers compared to the specialty tests, which were labor intensive and needed highly skilled lab technicians to conduct the tests, undertake the analyses, and prepare the reports explaining the results. Although physicians ordered the laboratory tests Hill Country Labs performed the tests on their patients. Billing costs and collection varied greatly between parties being billed. These costs were lowest when the physician was billed, highest when the patient was billed, and in- between these extremes when other parties such as Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance companies or employers were billed. To reflect these differences, which were significant, Hill Country Labs charged different prices for the tests, depending on the party being billed. In addition, the price difference between tests billed to third parties and tests billed to the physicians or patients reflected the limitations imposed by fee schedules under which Medicare and Medicaid made payments. At the end of 2019, Hill Country Labs faced intense competition from national and local independent laboratories. The area was well known for its concentration of military medical facilities, especially in nearby San Antonio. In addition, managed care organizations, Medicare, || and Medicaid has all increased their efforts to control costs and utilization of health care services, and these efforts had negatively impacted Hill Country Lab's operating margins for the past few years. In response to the intense competition and price pressure, Isabella Sedge launched a media campaign in 2020 to promote Hill Country Lab's accuracy, responsiveness, and flexibility. In addition, she positioned the company as a state-of-the-art clinical laboratory to attract additional contracts for clinical research trials of new drugs, oncology testing, occupational drug testing, and other specialized services. As support for the marketing initiative, the company also made significant investment in the latest laboratory equipment. Preparation for 2020 Operating Plan In November 2019, Sedge approved the 2020 profit plan Garcia had prepared (see Exhibit 1). To estimate revenues, Garcia first considered the existing customer base and industry trends to predict the total number of tests the laboratory would perform in 2020. Second, he projected how many of those tests would be routine tests and how many would be specialty tests. Third, Garcia estimated what proportion of tests would be billed to physicians, patients, or other payers such as Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance companies. Fourth, Garcia obtained the forecasted average price per test by type and billing party from Hill Country Labs' director of billing and reimbursement (see Exhibit 1). Fifth, he performed a final review of the estimated volume by test type and billing party and calculated Hill Country Labs' total projected revenue for 2020. In preparing the 2020 budgeted expenses, Garcia had worked with Amy Chu, the company's manager of operations. Chu had joined Hill Country Labs in September 2019. She had been hired because of her reputation for astute management and cost control, while previously employed at a competing clinical lab. In fact, Chu's employment contract stipulated that she would receive as much as a 20% annual bonus based on how effectively, and efficiently, she managed the overall operations of the lab. Garcia and Chu used the following information in preparing budgeted expenses. 1. Materials cos was expected to vary with the number of tests. The material cost related to both routine tests and specialty tests was expected to be approximately the same. 2. Labor costs for routine tests was expected to vary with the number of routine tests. The projected annual labor hours for routine tests was 200,000 at an average wage of $12.00 an hour. Labor cost for the specialty tests was expected to vary with the number of specialty tests. The projected annual labor hours for specialty tests was 80,000 hours at $25.00 an hour. 3. Furniture and equipment were depreciated on a straight-line basis. 4. Other costs of testing consisted primarily of additional labor, utilities, maintenance, and sanitation. Of the total amount budgeted, approximately $300,000 was expected to be fixed, and the remainder was expected to vary with the number of tests performed. 5. Billing and collection costs were budgeted at $0.50 per test for tests billed to the physician, $3.50 per test for tests billed to the patient, and $3.00 per test for the tests billed to the patient's insurance company. 6. Advertising and promotion costs were budgeted at $820,000 and were independent of test volume. 7. The executive management team expected to receive salaries and bonuses totaling $700,000. 8. Other administrative costs were expected to be fixed at $500,000. Actual Results Compared to Plan As part of his analysis of actual profit compared with planned profit, Garcia summarized several statistics relative to 2020 actual performance regarding the number of tests, the mix of routine and specialty tests, the mix of payers, and the price of the tests (see Exhibit 1). He noted that actual lab prices per test during 2020 were as predicted. In addition, the company's actual labor costs reflected the use of 189,788 hour for routine tests at an average wage of $11.90 an hour, and 107,388 hours for specialty tests at an average wage of $25.10 an hour. Actual prices for lab materials used were the same as those included in the plan. The actual fixed costs included in "other costs of testing" were $8,000 higher than expected. During the year, Garcia had heard that Chu was doing a good job as the operations manager. Chu had initiated some significant process improvements to reduce the amount of materials use and waste, and she routinely recognized employee initiatives for improving efficiencies. Garcia knew that Chu hoped to receive a bonus for her performance in 2020, and this added another dimension to the importance of learning more about the actual operating expenses for the year. Therefore, Garcia arranged a meeting with Chu to go over the 2020 actual operating results. He hoped his investigation would not only enable him to answer Sedge's questions but would also give him useful insights into why actual expenses differed from the original plan. He was still puzzled by the fact that Chu's process improvements had not seemed to enhance profits very much. Exhibit 1 Hill Country Labs, Inc. 2020 Operating Statement Actual Planned Net revenue Routine testing $11,676,904 $12,160,000 Specialty testing 5,709,496 4,240,000 Total net revenue $17,386,400 $16,400,000 Materials $2,760,000 $2,700,000 Labor-routine 2,258,475 2,400,000 Labor - specialty 2,695,434 2,000,000 Depreciation 3,503,000 3,500,000 Other costs of testing 1,120,000 1,100,000 Billing and collection costs 2,080,000 1,850,000 Advertising and promotion 892,000 820,000 Management salaries 710,000 700,000 Other administrative costs 510,000 500,000 Total expenses $16.528,909 $15.570,000 Net Profit $857.491 $830.000 Number of tests per year 1,030,000 1,000,000 % of tests - routine 74% 80% % of tests-specialty 26% 20% % of tests paid by physicians 44% 50% % of tests paid by patient 20% 20% % of tests paid by other parties 36% 30% Price for routine test Physician pays $14.00 $14.00 Patient pays $17.00 $17.00 Other party pays $16.00 $16.00 Price for specialty test Physician pays $20.00 $20.00 Patient pays $23.00 $23.00 Other party pays $22.00 $22.00

part 1

part 1 part 2

part 2 part 3

part 3 part 4

part 4 Lastly part 5

Lastly part 5