after reading the case "meridian credit union: taking on the big banks" . Explain in detail about the following

1. Porter'sfive forces model

2. SWOT Analysis

3. PEST Analysis

4. Business level statergies used by it

5. Corporate level statergies used by it

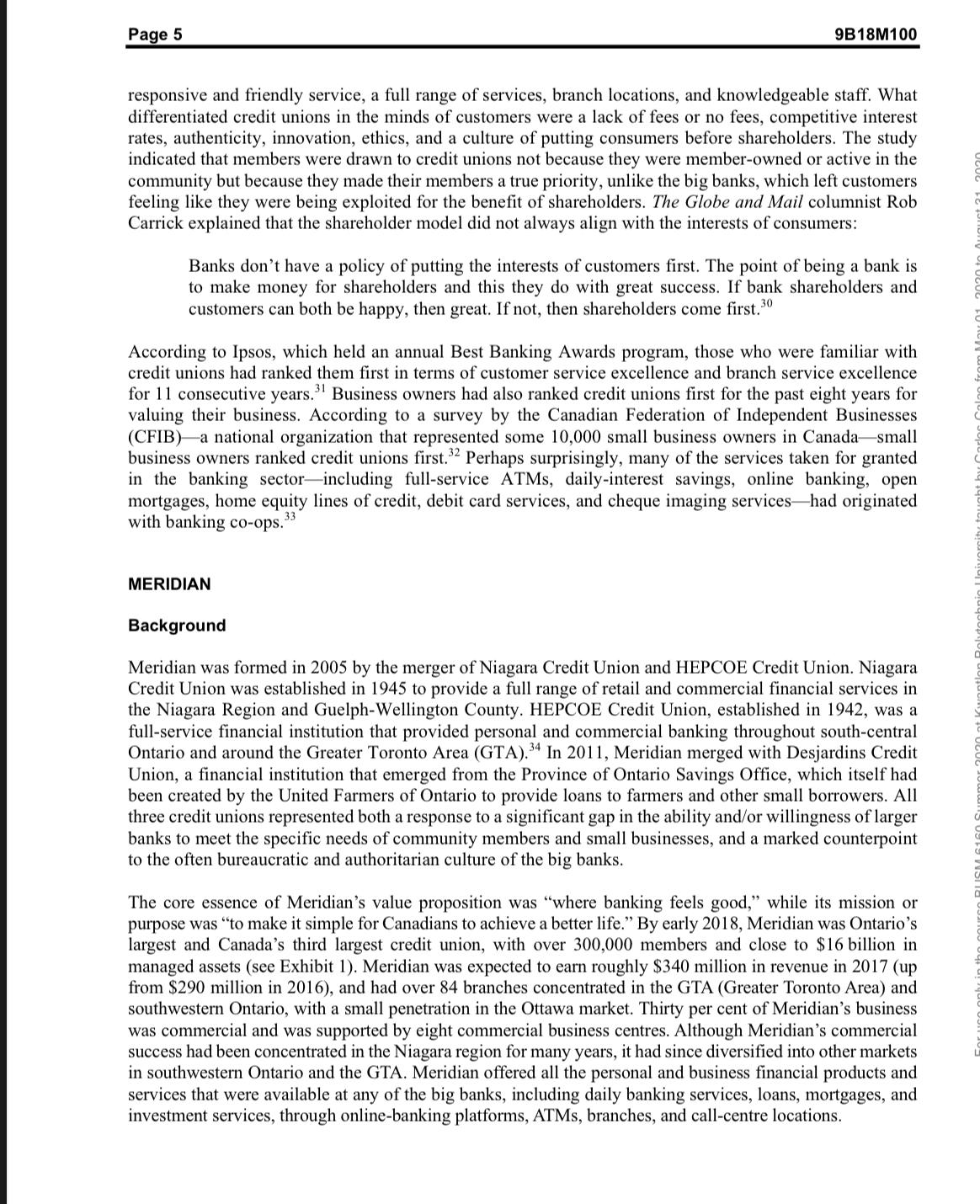

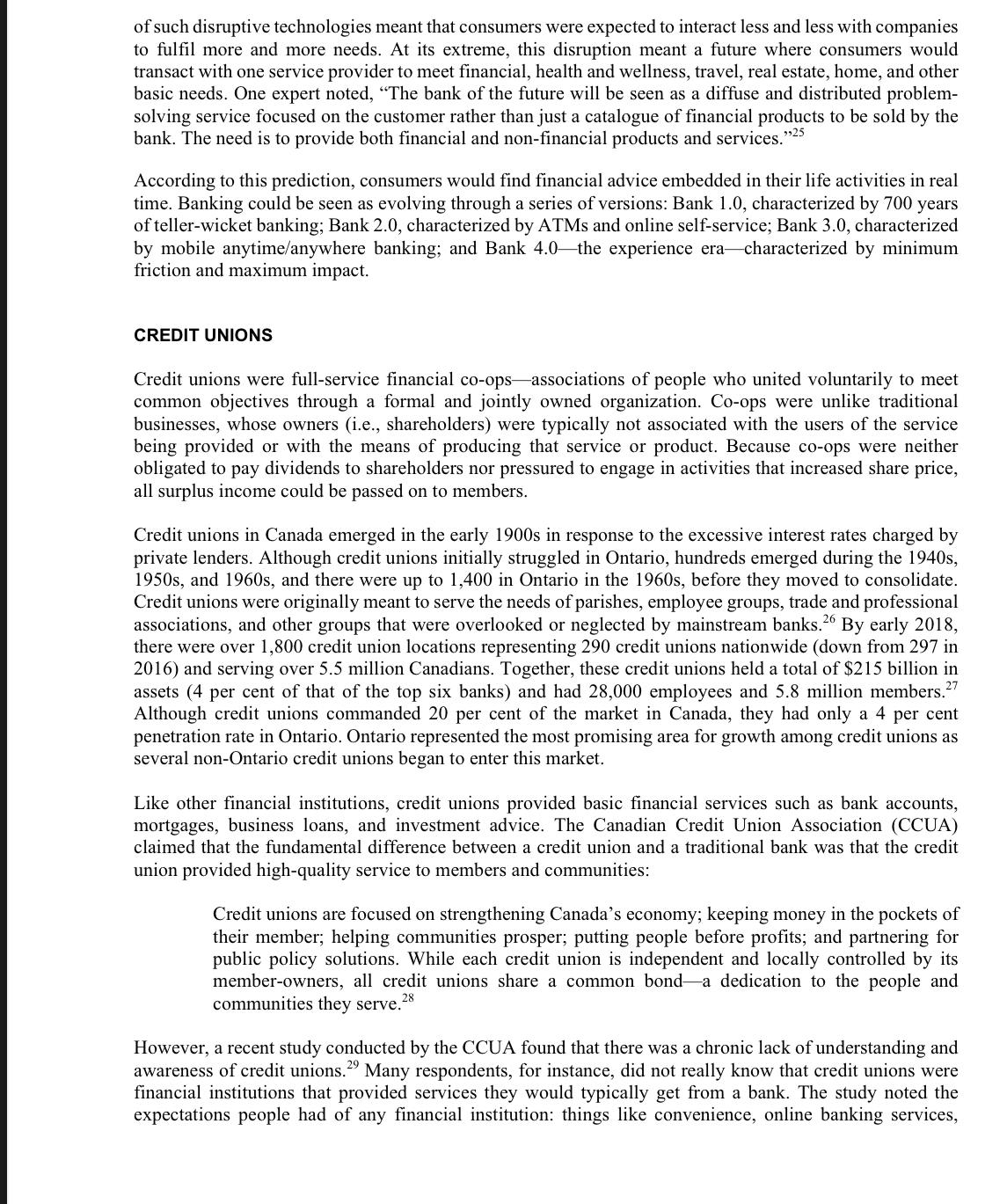

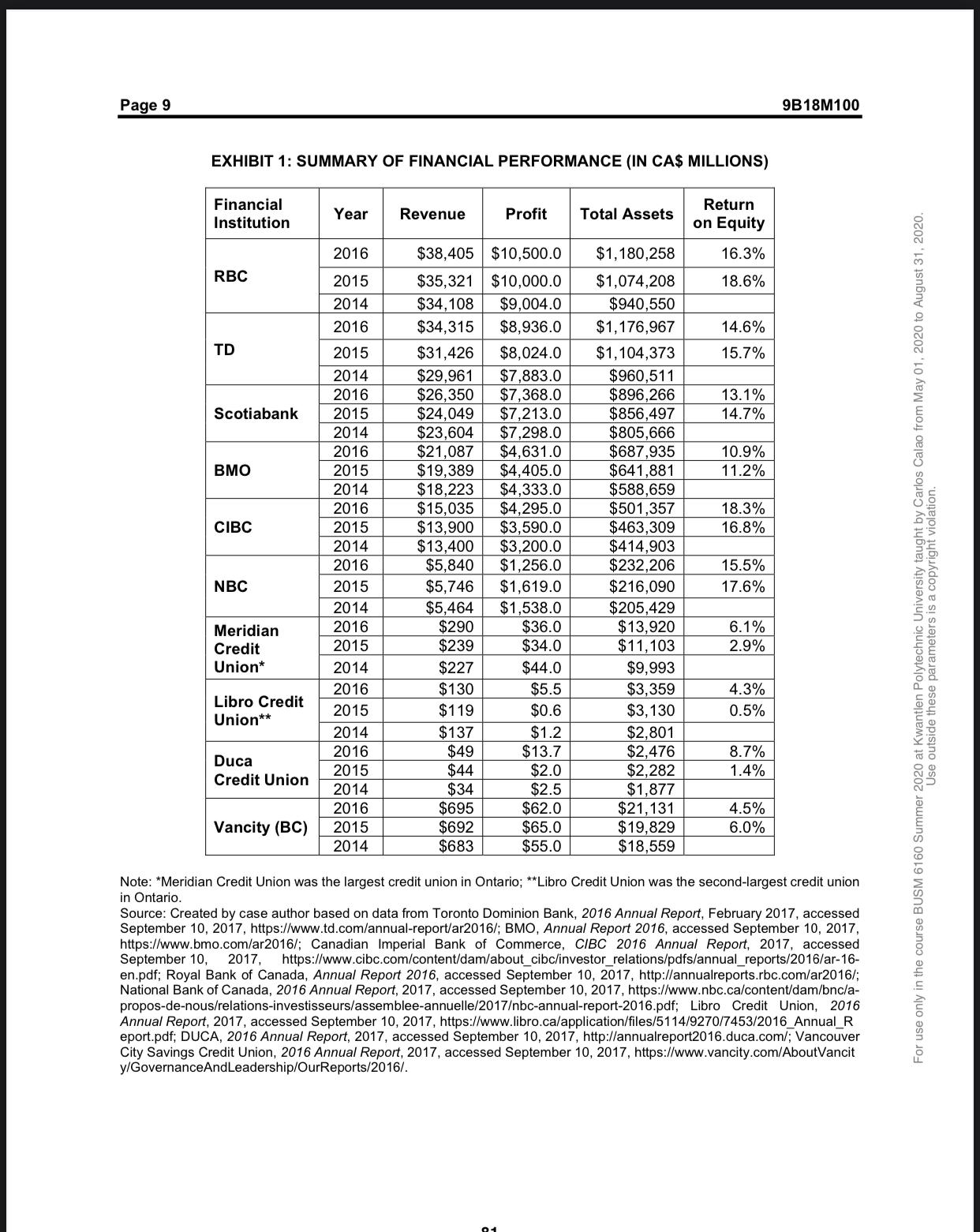

Regulatory Environment The Canadian government had generally sought to protect Canada's big banks. For instance, because of the requirement that large banks be widely held, it was impossible for any large Canadian bank to be foreign controlled.4 The big banks were also quite well protected from domestic competition. Although credit unions emerged as potential competitors to the big banks, they were provincially regulated, which made it difcult for them to compete at a national level because of variations in regulation across provinces and limitations on doing business across provinces. While the Canadian government offered credit unions the opportunity to establish themselves federally, the process of making this transition remained ambiguous, and lingering inequities put federal credit unions at a disadvantage relative to their banking counterparts, whichunlike credit unionswere able to rely on multiple institutions to leverage limits on deposit insurance. The banks' oligopoly was further entrenched by a past change to the Bank Act, which allowed banks to engage in a broad range of nancial services. They could manage trusts, sell insurance, and underwrite corporate securities5 (primarily through afliated entities), and this allowed them to further cement their dominant market position. Although the govemment's protection of the banks originated partly from its history of exercising control over them, the big banks, through the Canadian Bankers Association, had actively lobbied for regulations that would preserve their market position. Recently, they had almost succeeded in persuading the government to pass a regulation that would prohibit non-chartered banks (e.g., credit unions) from using the word \"bank," or any derivative, in any communicationsbecause, as the banks claimed, this use was causing market confusion.El This attitude of superiority on the part of the big banks also played out in their relationships with consumers, and the banks' historical ties to government encouraged an authoritarian approach toward consumers. Instead of seeing consumers as valuable customers, the banks tended to expect consumers to view receiving banking services as a privilege.1r Studies conrmed that, as a result, the big banks in Canada had struggled to develop strong relationships with customers.8 That said, a recent survey had found that Canadians trusted the big banks: 84 per cent of Canadians had a favourable impression of Canadian banks, and 93 per cent of respondents had a favourable impreSsion of the bank they did most of their business with. Overall, Canadians tended to associate the high protability of the big banks with stability and security in the Canadian economy. Responsible Banking Together, the six big banks spent close to $1 billion on a wide range of corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives in 2016. CIBC, for instance, said in its CSR report that it was \"committed to creating value for [its] clients, employees, communities, and . . . stakeholders.\" Its landmark CSR activity was the CIBC Run for the Cure, a major event that raised up to $1? million in 2016 for breast cancer research.\" In its 2016 CSR report, RBC stated that it contributed $100 million in donations, sponsorship and community investments and achieved a 24.5 per Cent drop in the C02 emissions of its operations. RBC also claimed to be one of the largest purchasers of renewable energy and articulated its organizational purpose as \"helping clients thrive and Communities prosper."ll BMO funded a nationwide nancial literacy program that aimed to educate 45,000 students about personal nance over three years, while its policy on board diversity ensured that women represented at least one-third of the bank's independent directors. '2 TD divided its CSR into four categories: responsible banking, strengthening communities, building an extraordinary workplace, and being an environmental leader. TD said that it aimed \"to enable better, more prosperous lives by taking a more human approach to everything that we do."13 The bank invested over $15 million to support nancial education programs across North America and the United Kingdom, and over 3,000 TD employees volunteered each year to teach free nancial seminars.\" On top of that, \"TD Forests\" had protected 48'? hectares of critical forest habitat across North America since 2012.15 Negtected Social Issues Although the growth of attention to social and environmental issues among the big banks had been substantial, there were at least three social issues they had failed to address. First, Canadian debt levels were at an all-time high. Growing criticism of the big banks pointed to exploitative lending practices and suggested banks searched for gaps in consumer knowledge in order to impose the maximum amount of credit possible on consumers without them defaulting.Its Indeed, a scathing report by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) found that big banks were pressuring front-line employees to sell consumers products they didn't need. Bank employees interviewed by CBC said things like, \"I felt like I'm not really helping my clients,\" \"I'm not making their life easier . . . I put them into more debt,\" \"We have a script to follow, and if the customer says 'no' you have to rebut them at least three times?\" A report from an equity research firm in Toronto that examined the ease with which consumers could get mortgages found that banks were bending over backward to make it easy for customers to buy. It noted, \"At one sales centre, Bank of Montreal (BMO) was willing to lend half of the required 20 per cent down payment. Apparently, BMO is qualifying the prospective borrower on the full mortgage before approving the down-payment loan?\" The second, related issue was poor financial literacy in Canada, where over 60 per cent of Canadian adults rated their nancial knowledge as \"fair" or \"poor," 3 out of 10 Canadians lacked condence in their financial knowledge, and 46 per cent of national youth scored a C or worse on a basic financial literacy test.\" In an environment where consumers were nancially illiterate, the consumer knowledge that would otherwise deter egregious lending practices was weak or non-existent. This meant that a growing portion of economic value was diverted away from other segments of society and toward financial institutions. The unprecedented 3035 per cent net income margins of big banks spoke to this very point. The third issue was the payday loan industry. Payday loans were small, unsecured loans that were due on the borrowers\" next payday; they were designed to relieve urgent, short-term cash needs. The payday loan industry provided $2.5 billion in loans to approximately 2 million households across Canada each year.\" These trends suggested that there was a relatively large untapped market for nancial servicesa market that few nancial institutions had chosen to pursue (an exception was Vancity Fair and Fast Loan\"). However, the feasibility of the payday loan business model was based on repeat customers. That is, payday loan companies struggled to make a prot if they made small loans to a high number of customers once or twice. Instead, they had to build consumers' dependence on payday loans by pushing loans with interest charges that borrowers could not pay in time, thus initiating a never-ending series of loans. The Future of Banklng Analysts had remarked on the looming impact of technology on the financial services industry, saying that it would severely disrupt the status quo.22 Financial technology (ntech) was most commonly thought of in the industry as those mechanisms that cut through the more inconvenient and traditional forms of banking that had become institutionalized over the past several decades. Although they had become mundane, automated teller machines (ATMs) had represented radical technology advancement in the 19805 and started a revolution away from branch banking. Now, inconvenient forms ofday-to-day banking were being disrupted by the introduction of email money transfers, web and mobile banking, electronic money transfers, and image-capture cheque cashing.\" Blockchain was expected to severely threaten the traditional banking model because the revolutionary platform would remove the need for banking intermediaries to facilitate money transfers. The basic notion of having a legitimate third party (Le, a nancial institution) deposit funds from one party and distribute them as loans to another party was threatened by blockchain's peer-to-peer, self-enforcing lending platform. This was especially important given the growing number of Canadiansespecially young Canadiansengaging in 'inge financial services like hlockchain?'1 The use MERIDIAN CREDIT UNION: TAKING ON THE BIG BANKS Mike Valente wrote this case solely to provide material for class discussion. The author does not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The author may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality. This publication may not be transmitted, photocopied, digitized, or otherwise reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the copyright holder. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Business School, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada, N6G ON1; (t) 519.661.3208; (e) cases@ivey.ca; www.iveycases.com. Copyright @ 2018, Ivey Business School Foundation Version: 2018-07-06 Meridian Credit Union (Meridian) was an Ontario-based co-operative (co-op) bank with over 300,000 members (i.e., customers) and close to CA$16 billion' in assets. Unlike chartered banks, credit unions possessed a co-op ownership structure, where customers, not shareholders, owned the financial institution. Meridian had an intimate relationship with its members and an authentic commitment to the communities in which it resided, something the big banks often struggled to achieve. Although credit unions had been around for over 100 years, they had struggled to achieve a significant market share relative to Canada's big banks in Ontario and beyond. Since 2014, however, Meridian had experienced tremendous growth in its membership base and had been able to capture a modest slice of the big banks' customer base. In March 2018, Meridian's executive team reflected on this recent growth and the changes the growth had made to Meridian. It was time to think about where Meridian should go from here. THE CANADIAN FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY The financial services industry in Canada was concentrated. Six banks-TD Canada Trust (TD), Bank of r 2020 at Kwantlen Polytechnic University taught by Carlos Calao from May 01, 2020 to August 31, 2020 Use outside these parameters is a copyright violation. Montreal (BMO), The Bank of Nova Scotia (Scotiabank), Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC), Royal Bank of Canada (RBC), and National Bank of Canada (NBC)-claimed roughly 80 per cent of total industry assets." Financial performance in the industry had been nothing short of stellar. Total revenues in 2016 across the six banks amounted to $141 billion (a 9 per cent increase from 2015), and profits added up to $36.9 billion (a 5.7 per cent increase from 2015). The banks had enjoyed similar increases over the past several years. Although average return on equity (ROE) across the big banks had declined from 15.8 per cent in 2015 to 14.8 per cent in 2016, it remained higher than asset growth, meaning that the big banks had been able to grow their assets while maintaining healthy financial margins. Revenues of most financial institutions (e.g., banks and credit unions) were lumped into two main categories: interest income and non-interest income. Interest income made up approximately 56 per cent of the revenue of the largest banks' and was generated from what was known as the "spread." The spread was he difference between the interest a bank earned on its loans to customers and the interest it paid to depositors and other creditors for the use of their money. Non-interest income, which made up the remaining For use only in the course BUSM 6160 Summer 2 44 per cent of big bank revenue, represented a variety of value-added services including securities trading, providing assistance for companies issuing new equity financing, personal banking service fees, commissions on securities, and wealth management.Page 5 9B18M100 responsive and friendly service, a full range of services, branch locations, and knowledgeable staff. What differentiated credit unions in the minds of customers were a lack of fees or no fees, competitive interest rates, authenticity, innovation, ethics, and a culture of putting consumers before shareholders. The study indicated that members were drawn to credit unions not because they were member-owned or active in the community but because they made their members a true priority, unlike the big banks, which left customers feeling like they were being exploited for the benefit of shareholders. The Globe and Mail columnist Rob Carrick explained that the shareholder model did not always align with the interests of consumers: Banks don't have a policy of putting the interests of customers first. The point of being a bank is to make money for shareholders and this they do with great success. If bank shareholders and customers can both be happy, then great. If not, then shareholders come first." According to Ipsos, which held an annual Best Banking Awards program, those who were familiar with credit unions had ranked them first in terms of customer service excellence and branch service excellence for 1 1 consecutive years." Business owners had also ranked credit unions first for the past eight years for valuing their business. According to a survey by the Canadian Federation of Independent Businesses CFIB)-a national organization that represented some 10,000 small business owners in Canada-small business owners ranked credit unions first." Perhaps surprisingly, many of the services taken for granted in the banking sector-including full-service ATMs, daily-interest savings, online banking, open mortgages, home equity lines of credit, debit card services, and cheque imaging services-had originated with banking co-ops. $3 MERIDIAN Background Meridian was formed in 2005 by the merger of Niagara Credit Union and HEPCOE Credit Union. Niagara Credit Union was established in 1945 to provide a full range of retail and commercial financial services in the Niagara Region and Guelph-Wellington County. HEPCOE Credit Union, established in 1942, was a full-service financial institution that provided personal and commercial banking throughout south-central Ontario and around the Greater Toronto Area (GTA)." In 2011, Meridian merged with Desjardins Credit Union, a financial institution that emerged from the Province of Ontario Savings Office, which itself had been created by the United Farmers of Ontario to provide loans to farmers and other small borrowers. All three credit unions represented both a response to a significant gap in the ability and/or willingness of larger banks to meet the specific needs of community members and small businesses, and a marked counterpoint to the often bureaucratic and authoritarian culture of the big banks. The core essence of Meridian's value proposition was "where banking feels good," while its mission or purpose was "to make it simple for Canadians to achieve a better life." By early 2018, Meridian was Ontario's largest and Canada's third largest credit union, with over 300,000 members and close to $16 billion in managed assets (see Exhibit 1). Meridian was expected to earn roughly $340 million in revenue in 2017 (up from $290 million in 2016), and had over 84 branches concentrated in the GTA (Greater Toronto Area) and southwestern Ontario, with a small penetration in the Ottawa market. Thirty per cent of Meridian's business was commercial and was supported by eight commercial business centres. Although Meridian's commercial success had been concentrated in the Niagara region for many years, it had since diversified into other markets in southwestern Ontario and the GTA. Meridian offered all the personal and business financial products and services that were available at any of the big banks, including daily banking services, loans, mortgages, and investment services, through online-banking platforms, ATMs, branches, and call-centre locations.Pa 9 6 9318M1 00 Strategic Imperatives Meridian aspired to become \"a much larger nancial services partner\" so that it would be perceived as relevant and sustainable in the mainstream marketplace. This aspiration shifted it away om the fringe or niche market segments that had characterized its business model in early days. To that end, in 2015, Meridian established its Blueprint for Growth, which evolved into ve key strategic imperatives. Differentiated Member Experience Meridian believed that any growth strategy must include strengthening and maintaining its differentiated member experience. Meridian's website claimed that it was there to support its members at all times because Meridian employees knew their members and their circumstances extremely well and thus had \"the ability and power to make decisions on the spot.\"5 The credit union called this the Meridian difference, claimed leadership in being a member-centric nancial services institution in Ontario and beyond, and counted on that leadership to fuel growth. Testimonials from current members supported this claim: \"lust switched over to Meridian Credit Union from TD, couldn't be happier! Much better customer service and overall better environment (everyone seems much happier).\" \"Meridian is denitely about the people! I know they always have my back. I am so done with Scotiabank and BBC. Thank you Meridian!\" Exceptional Employee Experience Driving this differentiated member experience was a unique, member-focused culture: members felt different walking into Meridian than they did in a traditional bank. Many employees were proud of the authentic relationships they had with consumers, in large part because the absence of shareholder demands afforded them the freedom to go out of their way to meet members' needs. Interestingly, many senior managers at Meridian headquarters had come from the big banks and were attracted to the unique value proposition Meridian offered to its members. Although they did have sales targets, Meridian executives claimed that Meridian's culture separated those targets from the aggressive sales targets of the big banks and even some credit unions.\"5 Consider the following quotations from employees: As a Senior Small Business Advisor with Meridian, I am able to act as a true advisor for the Small Business Community I serve. Daily, I work to achieve my goals; however, I do so by wearing my advisor hat and not my salesperson hat. . . . Since joining the team at Meridian, I have been able to re-ignite my passion for doing what I love to do. For me, my experience here has changed my life for the better. Meridian is a great company, with talented people \"dio care about what they do. As a Business Analyst, I collaborate with people across different departments, and the one common thing is that they are passionate. We have a great work culture that is collaborative, supportive, and the team is diverse. In 2017, Meridian was recognized as having one of Canada's most admired corporate cultures. The award was based on the credit union's leadership, which drove vision, mission, and values; its culture, which was aligned to that vision; and this culture's promotion and support of organizational and individual involvement in social issues.\" Social Commitment Meridian maintained its commitment to its existing members through community development, investing surplus earnings in its communities through sponsorships and donations. To Meridian, these initiatives Page 7 9318M100 represented important ways to communicate the credit union's commitment to the community and to attract members and employees. Meridian's commitment to communities was reected in ve main goals: improving nancial literacy, investing in communities, engaging employees, contributing to a healthier environment, and supporting a strong co-op sector. Meridian aimed to improve nancial literacy by educating members about how to \"better manage their money and grow their lives,\" for example, by helping Canadian families learn how to save for their children's education. It invested in communities by using surplus income from operations to fund community programs andfor to partner with community organizations identied by local employees. Meridian engaged employees by encouraging them to support their communities; it did so by matching employees' personal donations of up to $1,000 and by donating $12.50 for each hour an employee volunteered (up to $500) to any charity the employee chose. Meridian's contribution to a healthier environment involved assessing and minimizing the company's environmental impact. Its support of a strong co-op sector involved educating high school students about coops, supporting conferences related to coops, and promoting coop problem solving through its Cooperative Young Leaders program. Market and Membership Growth To drive membership growth, Meridian aggressively promoted attractive product offerings with some of the best rates on the market across its inbranch and digital platforms. For example, in July 2016, Meridian's 2.44 per cent fiveyear xed mortgage was lowest, next to BMO's 2.49 per cent and TD's 2.59 per cent. Meridian was also proud of being the rst nancial institution in Canada to offer a 1.49 per cent 12-month mortgage rate. Meridian had also been promoting high-interest savings accounts at 1.5 per cent, whereas competing nancial institutions offered somewhere between 0.5 per cent and 0.9 per cent, depending on various conditions. In perhaps a more direct effort to increase market share, Meridian offered a special savings rate to new members who deposited money at Meridian. This initiative also targeted existing members who deposited new money into the credit union. Overall, Meridian's membership growth had been explosive: it had 20,000 new members in 2016, and its growth in new members for 2017 was expected to be similar if not better than in 2016. Di idBin M 1 As part of its diversication effort, Meridian purchased a leasing company in 2016 and established Meridian OneCap Credit Corp. (OneCap) to help expand its brand nationally. With a client base of approximately 23,000, OneCap provided equipment leasing and loan nancing solutions and value-added services to the small- and mid-market equipment finance market. By the end of September 2016, OneCap's portfolio totalled close to $1 billion. In August 2016, Meridian announced it would establish a national bank as a subsidiary, using a digital retail platformthat is, it would have no physical branch locations. The bank would be structured as a subsidiary of the parent co-op based in Ontario, meaning Meridian members in Ontario would essentially own the bank. Importantly, however, Meridian bank customers would not own the bank or the credit union. AFr'nancr'a! Post article quoted chief executive ofcer (CEO) Bill Maurin as explaining that his intention was to compete directly with the country's big banks: \"There 's not a lot of Canadian love for the big banks, but we think there can be a lot of love for a Meridian version?\" Meridian sought to use this expansion strategy to compete against other mobile and online banks such as Tangerine, a unit of the Bank of Nova Scotia, by offering higher-interest savings rates and lower mortgage rates: \"We pride ourselves on being bold and feisty, and we will bring that philosophy to Meridian Bank." In explaining the decision to go with a bank rather than a credit union, Maurin said that it was best to expand across Canada as a bank, as that was \"the financial entity Pa 9 8 951BM100 Canadians were most used to. The understanding of credit unions is not where we'd want it to be.\" The CEO added that \"applying for a separate federal bank license would allow the credit union 'to preserve a lot of the benets we have,' including higher deposit insurance?\" Capital to Fund Growth Unlike the big banks, which relied on an almost endless supply of external capital, credit unions like Meridian had to be innovative to find the necessary mding to fuel their growth. Governmental efforts to cool the housing market in Canada in 2016 led to changes in the policy that affected nancial institutions' reliance on mortgage securitization as a form of funding. This left nancial institutions like credit unions at a disadvantage. In addition, recent efforts by the Ministry of Finance to extend Basel 111 rules related to the amount and type of capital required to achieve the minimum capital ratio would have a substantial impact on credit unions' ability to grow. As a result, efforts to implement Meridian's strategic imperatives were contingent on new capital. In response, Meridian had recently increased its issuance of share offerings to members in 2015 and 2017 at a promoted return rate of 4.004.25 per cent, which was more than the 1.5 per cent rate members typically earned through term deposits. These shares were non-voting, non- participating, and non-cumulative, making them slightly different from traditional shares of the big banks. By the end of 2017, Meridian's share of capital originating from member shares rose to 55 per cent, with the remaining mostly attributed to retained earnings. Although the share offering was helpful in identifying sources of capital, Meridian was eager to nd additional forms of capital to fund its growth. Future Place In the Canadian Financial Services Industry Meridian strived to be a leader in member-centric nancial services in the Canadian market, \"with a member experience that continues to be a differentiator and supports the Credit Union's growth aspirations to become a much larger financial services partner." Meridian was committed to delivering on the Meridian difference and helping build communities: it sought \"to not only acquire market share but also be a market maker.\"\" Meridian aimed to be strategically proactiveto exploit some of the opportunities presented by complacency in a nancial services sector that was vulnerable to technological disruption. Now was the time to reect on the success of its growth strategy and to consider some of the emerging trends in the marketplace (e.g., ntech) and the anticipated response by the big banks. Meridian also needed to consider some macroeconomic challenges. The Conference Board of Canada expected Canada's gross domestic product to increase to 2.6 per cent in 2017 and then to drop to 2 per cent in 2018 because of a decline in consumer spending and residential investment. Over the medium term, the Canadian economy was expected to grow at a modest rate of 1.8 per cent annually.41 In 2017, the Bank of Canada wound down its monetary stimulus by increasing interest rates twice. Barring any major surprises, interest rates were expected to rise gradually as the economy grew. By the end of 2017, it was apparent that federal and provincial policy measures were cooling the housing market, and this effect was expected to continue through 2018. It was therefore important to consider how and where Meridian should go strategically. Should it become more focused? Should it expand and diversify its service offerings? What were the risks of these strategies? What were the opportunities and threats of ntech? Were there other growth options Meridian should be considering in light of these trends? At the time of the case, Michael Valente was a member of the Meridian Credit Union Board of Directors. cl.. n..|..o....|....:.. IIi....-.-.:e.. gnui... 1.... n-4,". r'-|.... l.-. Il-.. n4 Fln a- A......e 4-H nnnn ...... .....|.. .'..u.... ......-..... nllE'll new on hum..." nnnn -a V"... r... of such disruptive technologies meant that consumers were expected to interact less and less with companies to full more and more needs. At its extreme, this disruption meant a future where consumers would transact with one service provider to meet nancial, health and wellness, travel, real estate, home, and other basic needs. One expert noted, \"The bank of the future will be seen as a diffuse and distributed problem- solving service focused on the customer rather than just a catalogue of nancial products to be sold by the bank. The need is to provide both nancial and non-nancial products and services."25 According to this prediction, consumers would nd nancial advice embedded in their life activities in real time. Banking could be seen as evolving through a series of versions: Bank 1.0, characterized by 100 years of teller-wicket banking; Bank 2.0, characterized by ATMs and online self-service; Bank 3.0, characterized by mobile anytime\" anywhere banking; and Bank 4.0the experience eracharacterized by minimum friction and maximum impact. CREDIT UNIONS Credit unions were full-service nancial co-opsassociations of people who united voluntarily to meet common objectives through a formal and jointly owned organization. Co-ops were unlike traditional businesses, whose owners (i.e., shareholders) were typically not associated with the users of the service being provided or with the means of producing that service or product. Because co-ops were neither obligated to pay dividends to shareholders nor pressured to engage in activities that increased share price, all surplus income could be passed on to members. Credit unions in Canada emerged in the early 19005 in response to the excessive interest rates charged by private lenders. Although credit unions initially struggled in Ontario, hundreds emerged during the 19405, 1950s, and 1960s, and there were up to 1,400 in Ontario in the 1960s, before they moved to consolidate. Credit unions were originally meant to serve the needs of parishes, employee groups, trade and professional associations, and other groups that were overlooked or neglected by mainstream banks.26 By early 2018, there were over 1,800 credit union locations representing 290 credit unions nationwide (down from 29'? in 2016) and serving over 5.5 million Canadians. Together, these credit unions held a total of $215 billion in assets (4 per cent of that of the top six banks) and had 28,000 employees and 5.8 million members.\" Although credit unions commanded 20 per cent of the market in Canada, they had only a 4 per cent penetration rate in Ontario. Ontario represented the most promising area for growth among credit unions as several non-Ontario credit unions began to enter this market. Like other nancial institutions, credit unions provided basic nancial services such as bank accounts, mortgages, business loans, and investment advice. The Canadian Credit Union Association (CCUA) claimed that the mdamental difference between a credit union and a traditional bank was that the credit union provided high-quality service to members and communities: Credit unions are focused on strengthening Canada's economy; keeping money in the pockets of their member; helping communities prosper; putting people before prots; and partnering for public policy solutions. While each credit union is independent and locally controlled by its member-owners, all credit unions share a common bonda dedication to the people and communities they serve.28 However, a recent study conducted by the CCUA found that there was a chronic lack of understanding and awareness of credit unions.\" Many respondents, for instance, did not really know that credit unions were nancial institutions that provided services they would typically get 'om a bank. The study noted the expectations people had of any nancial institution: things like convenience, online banking services, Page 9 9B 18M100 EXHIBIT 1: SUMMARY OF FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE (IN CA$ MILLIONS) Financial Institution Year Revenue Profit Total Assets Return on Equity 2016 $38,405 $10,500.0 $1, 180,258 16.3% RBC 2015 $35,321 $10,000.0 $1,074,208 18.6% 2014 $34, 108 $9,004.0 $940,550 2016 $34,315 $8,936.0 $1, 176,967 14.6% TD 2015 $31,426 $8,024.0 $1, 104,373 15.7% 2014 $29,961 $7,883.0 $960,511 2016 $26,350 $7,368.0 $896,266 13.1% Scotiabank 2015 $24,049 $7,213.0 $856,497 14.7% 2014 $23,604 $7,298.0 $805,666 2016 $21,087 $4,631.0 $687,935 10.9% BMO 2015 $19,389 $4,405.0 $641,881 11.2% 2014 $18,223 $4,333.0 $588,659 2016 $15,035 $4,295.0 $501,357 18.3% CIBC 2015 $13,900 $3,590.0 $463,309 16.8% 2014 $13,400 $3,200.0 $414,903 2016 $5,840 $1,256.0 $232,206 15.5% NBC 2015 $5,746 $1,619.0 $216,090 17.6% 2014 $5,464 $1,538.0 $205,429 Meridian 2016 $290 $36.0 $13,920 6.1% Credit 2015 $239 $34.0 $11, 103 2.9% Union 2014 $227 $44.0 $9,993 Libro Credit 2016 $130 $5.5 $3,359 4.3% Union* 2015 $119 $0.6 $3, 130 0.5% 2014 $137 $1.2 $2,801 Duca 2016 $49 $13.7 $2,476 8.7% Credit Union 2015 $44 $2.0 $2,282 1.4% 2014 $34 $2.5 $1,877 Use outside these parameters is a copyright violation. 2016 $695 $62.0 $21, 131 4.5% Vancity (BC) 2015 $692 $65.0 $ 19,829 6.0% 2014 $683 $55.0 $18,559 Note: *Meridian Credit Union was the largest credit union in Ontario; **Libro Credit Union was the second-largest credit union in Ontario. Source: Created by case author based on data from Toronto Dominion Bank, 2016 Annual Report, February 2017, accessed September 10, 2017, https://www.td.com/annual-report/ar2016/; BMO, Annual Report 2016, accessed September 10, 2017, September 10, https://www.bmo.com/ar2016/; Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, CIBC 2016 Annual Report, 2017, accessed 2017, https://www.cibc.com/content/dam/about_cibc/investor_relations/pdfs/annual_reports/2016/ar-16- en.pdf; Royal Bank of Canada, Annual Report 2016, accessed September 10, 2017, http://annualreports.roc.com/ar2016/; National Bank of Canada, 2016 Annual Report, 2017, accessed September 10, 2017, https://www.nbc.ca/content/dam/bnc/a- propos-de-nous/relations-investisseurs/assemblee-annuelle/2017bc-annual-report-2016.pdf; Libro Credit Union, 2016 Annual Report, 2017, accessed September 10, 2017, https://www.libro.ca/application/files/5114/9270/7453/2016_Annual_R eport.pdf; DUCA, 2016 Annual Report, 2017, accessed September 10, 2017, http://annualreport2016.duca.com/; Vancouver City Savings Credit Union, 2016 Annual Report, 2017, accessed September 10, 2017, https://www.vancity.com/AboutVancit y/GovernanceAndLeadership/OurReports/2016/. For use only in the course BUSM 6160 Summer 2020 at Kwantlen Polytechnic University taught by Carlos Calao from May 01, 2020 to August 31, 2020