Aligning organisational growth and core values at Akhuwat - LUMS Case

(Reading: Robbins & Judge - Chapter 16-Organizational Culture; Vanourek, B., & Vanourek, G. 2012. Triple crown leadership: Building excellent, ethical, and enduring organizations. McGraw-Hill; Waterman Jr, R. H., Peters, T. J., & Phillips, J. R. 1980. Structure is not organization. Business Horizons, 23(3), 14-26)

Assignment Questions

- Would you like to work in Akhuwat? Why or why not?

- To what extent are Akhuwat's core organisational values and principles evident in its actual operations and outcomes?

- What are the key issues facing Akhuwat in terms of employee alignment to the organisation's mission, vision and values?

- In view of the exponential growth of the organisation, offer some suggestions to Mr Atif Tufail to enable employee alignment with Akhuwat's mission, vision and values.

- To what extent are the lessons drawn from this case applicable in the corporate sector or in your own organisation?

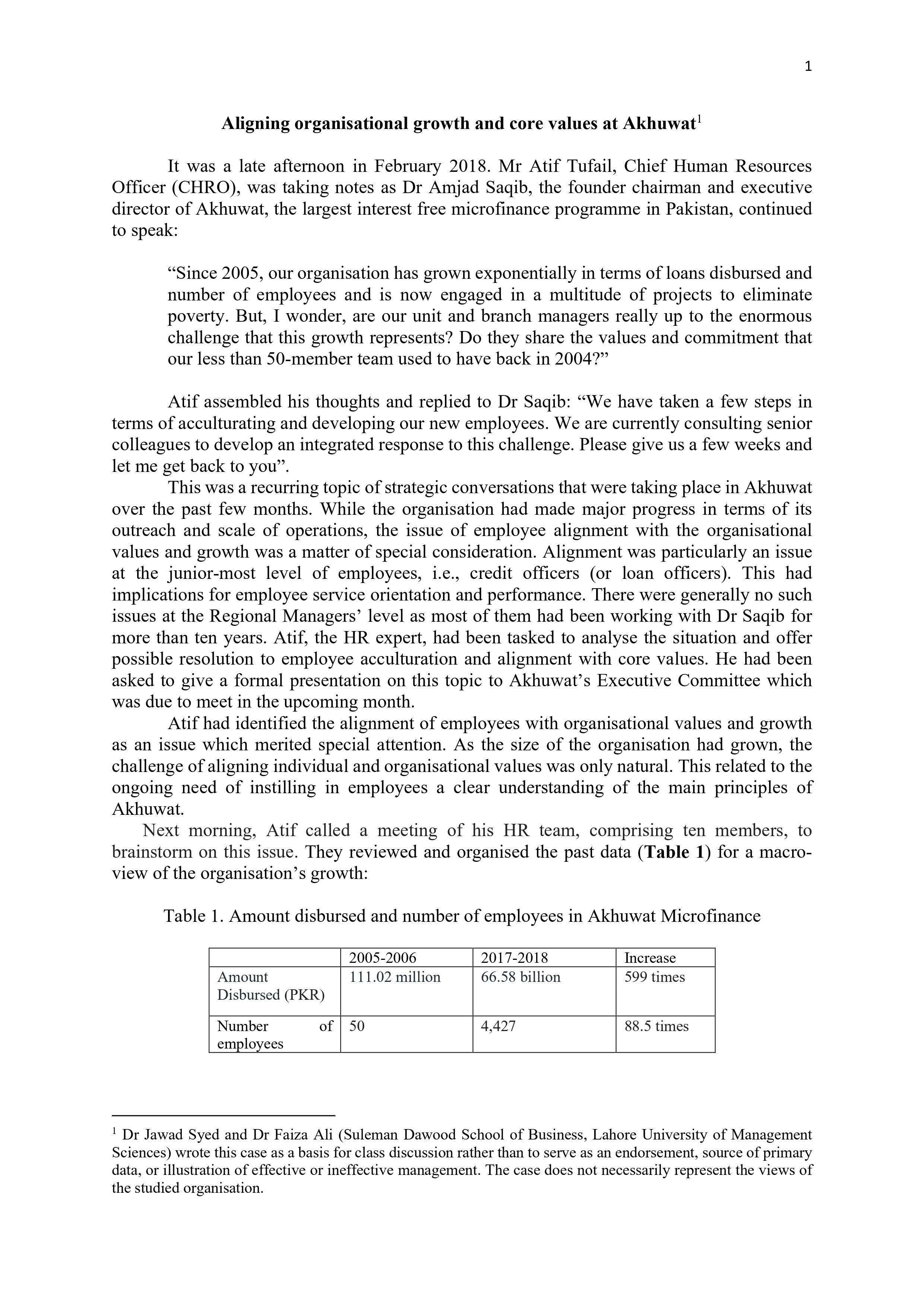

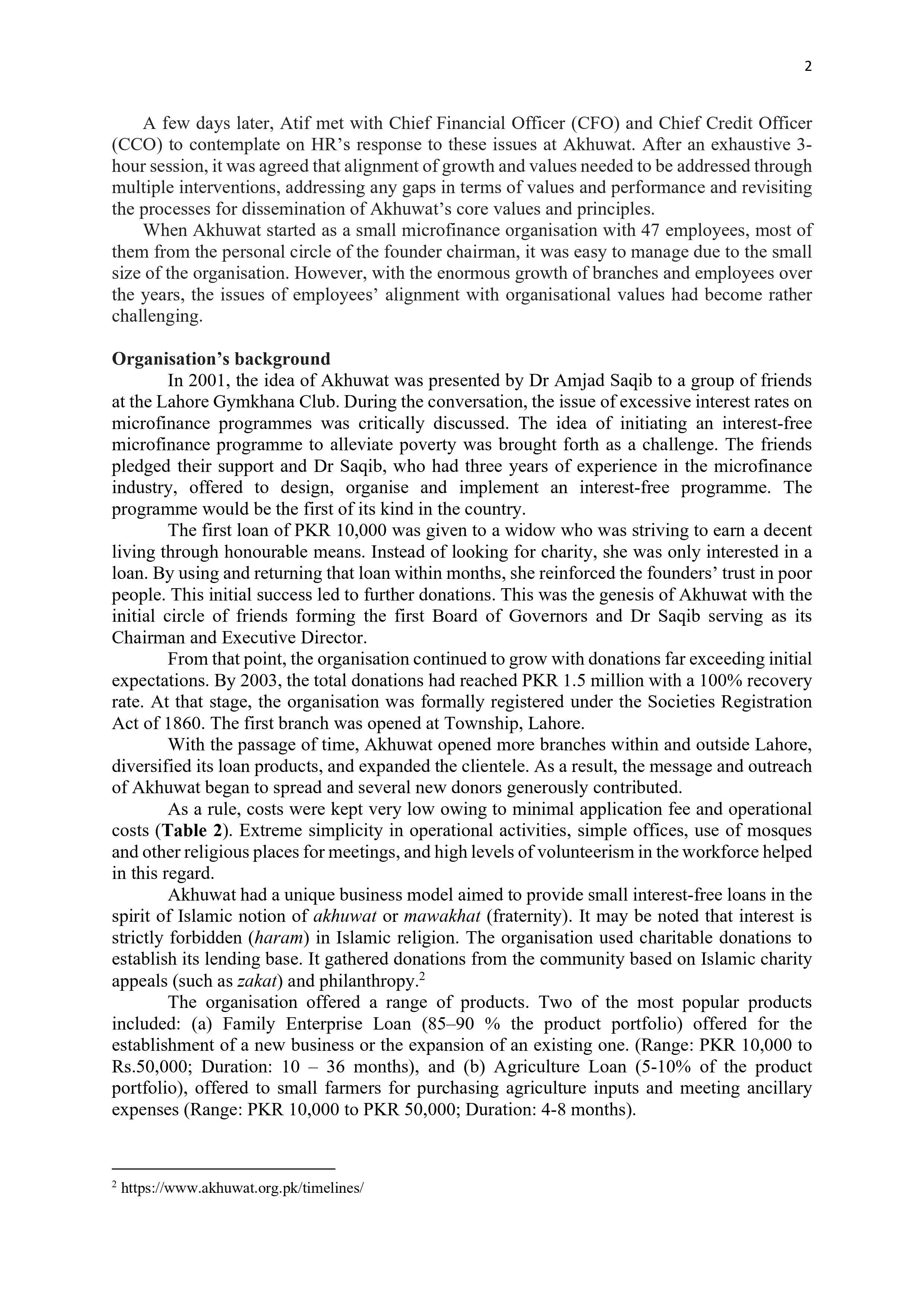

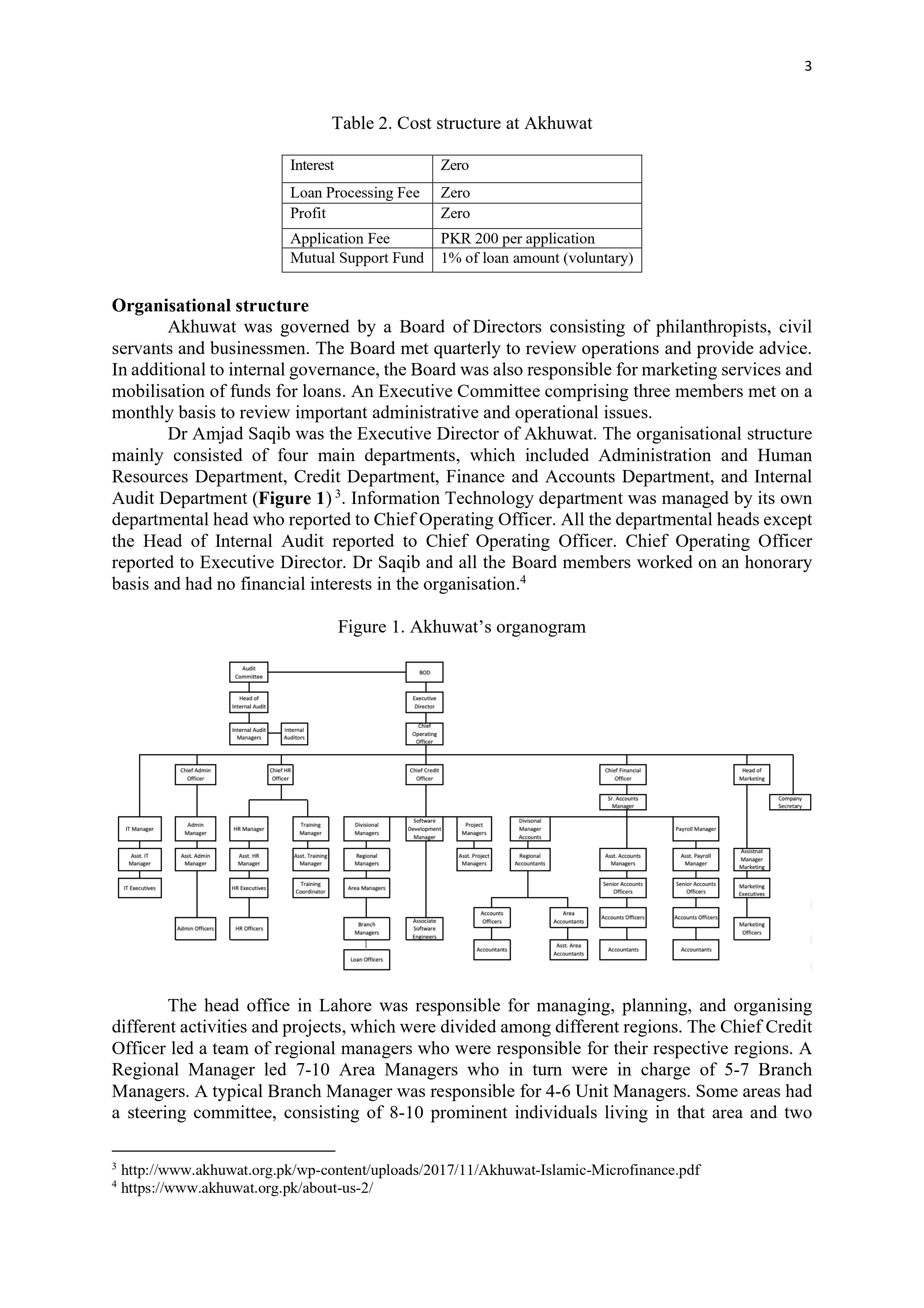

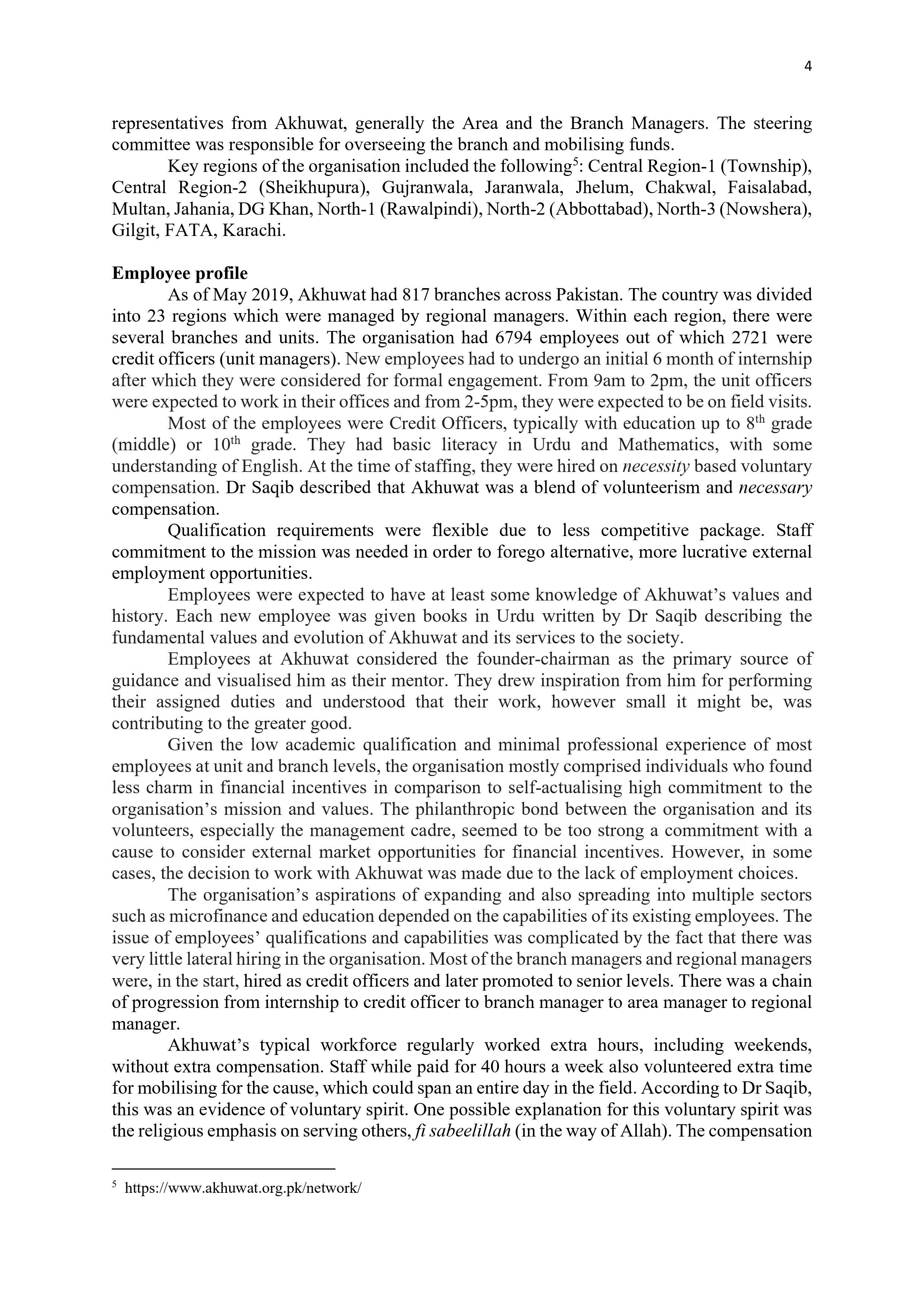

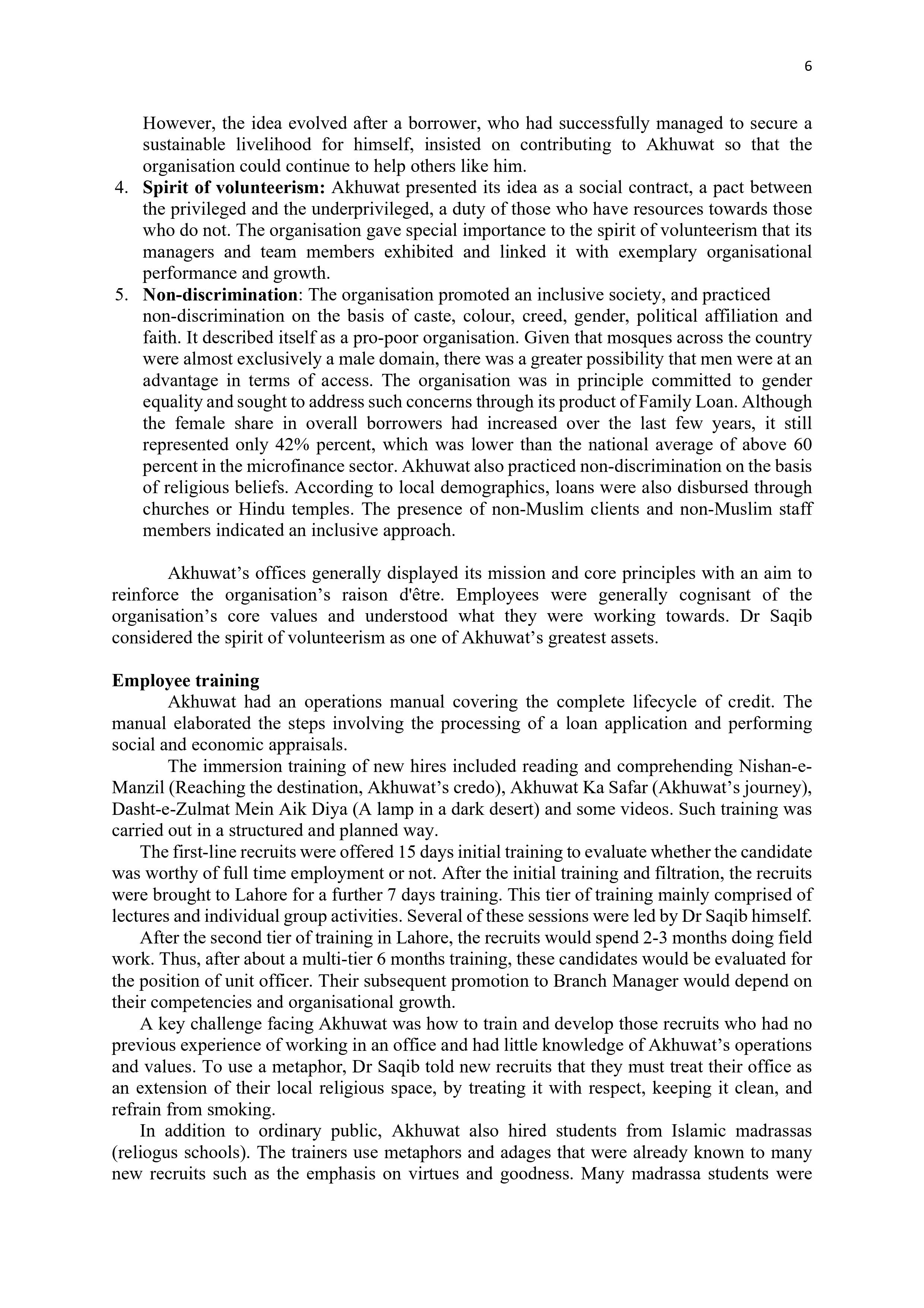

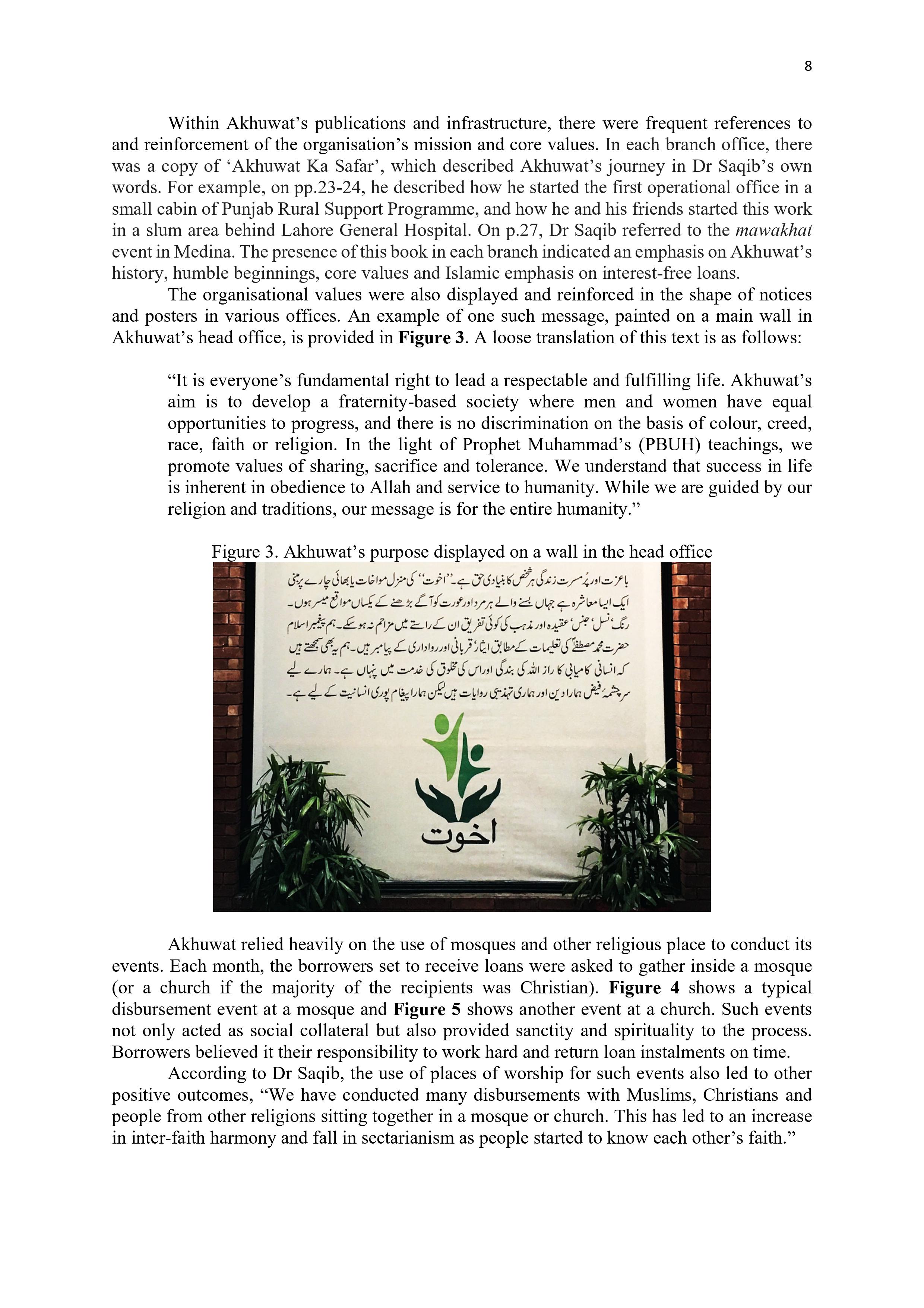

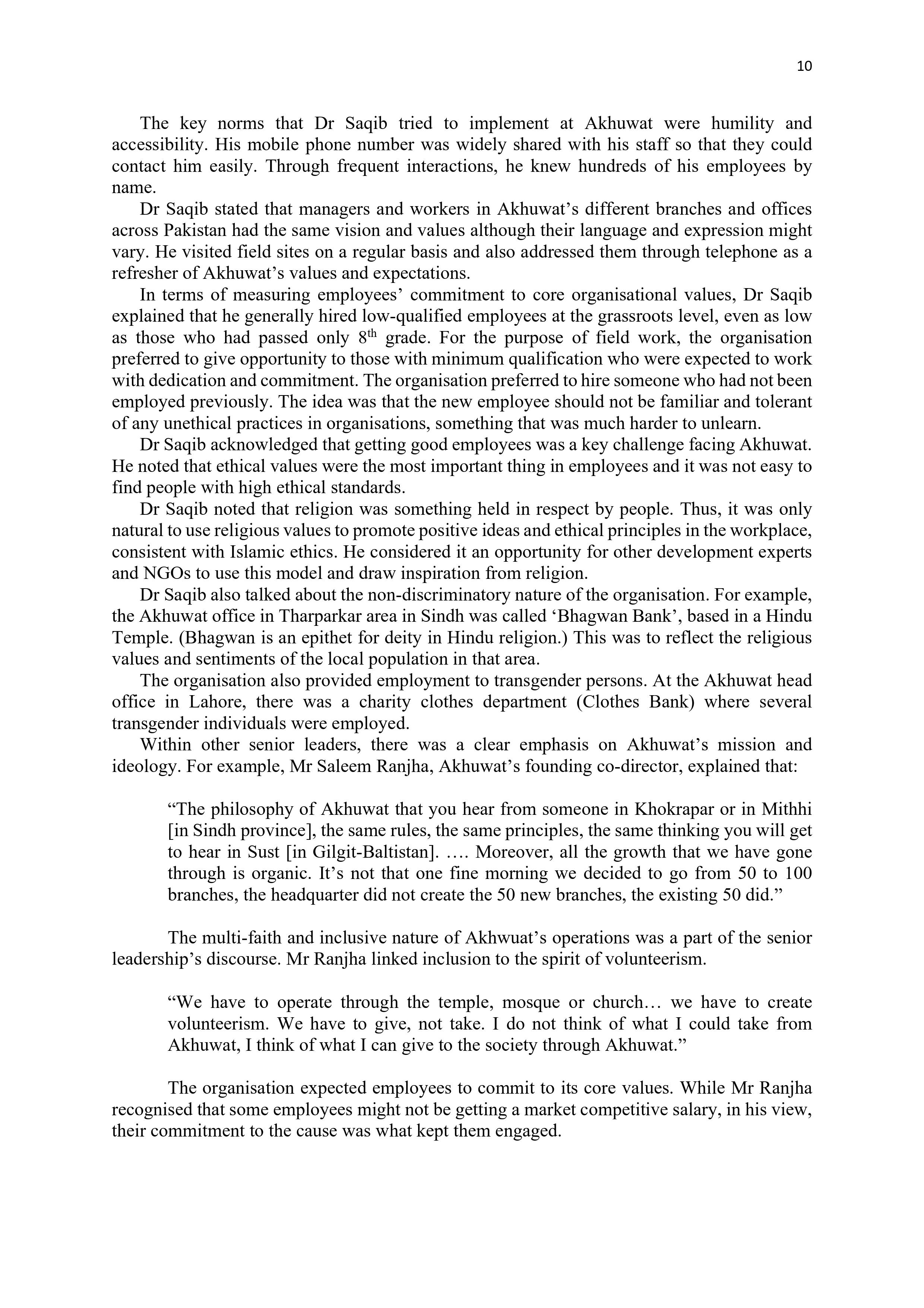

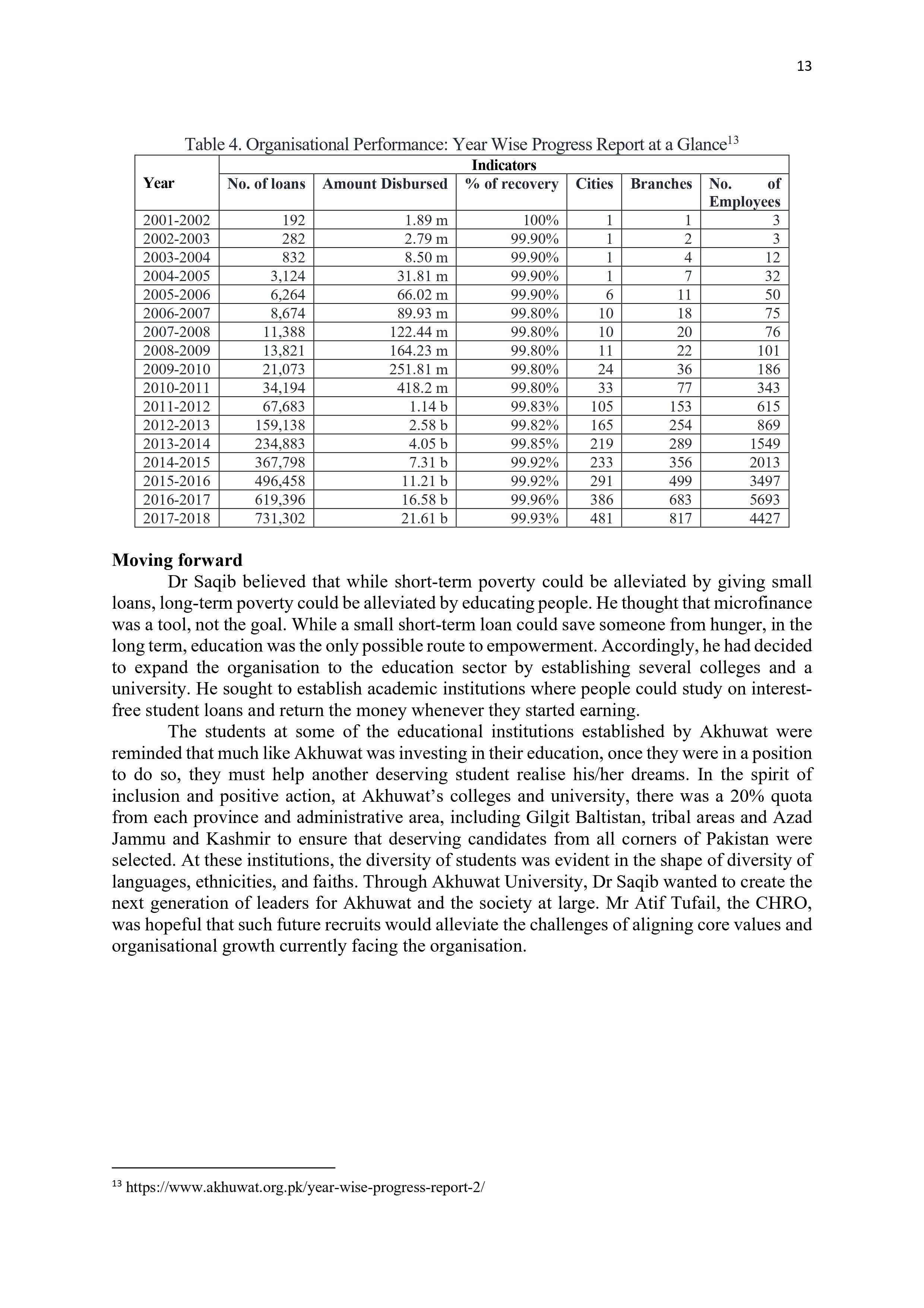

Aligning organisational growth and core values at Akhuwat1 It was a late afternoon in February 2018. Mr Atif Tufail, Chief Human Resources Ofcer (CHRO), was taking notes as Dr Amjad Saqib, the founder chairman and executive director of Akhuwat, the largest interest free micronance programme in Pakistan, continued to speak: \"Since 2005, our organisation has grown exponentially in terms of loans disbursed and number of employees and is now engaged in a multitude of projects to eliminate poverty. But, I wonder, are our unit and branch managers really up to the enormous challenge that this growth represents? Do they share the values and commitment that our less than 50member team used to have back in 2004?\" Atif assembled his thoughts and replied to Dr Saqib: \"We have taken a few steps in terms of acculturating and developing our new employees. We are currently consulting senior colleagues to develop an integrated response to this challenge. Please give us a few weeks and let me get back to you\". This was a recurring topic of strategic conversations that were taking place in Akhuwat over the past few months. While the organisation had made major progress in terms of its outreach and scale of operations, the issue of employee alignment with the organisational values and growth was a matter of special consideration. Alignment was particularly an issue at the junior-most level of employees, i.e., credit ofcers (or loan ofcers). This had implications for employee service orientation and performance. There were generally no such issues at the Regional Managers' level as most of them had been working with Dr Saqib for more than ten years. Atif, the HR expert, had been tasked to analyse the situation and offer possible resolution to employee acculturation and alignment with core values. He had been asked to give a formal presentation on this topic to Akhuwat's Executive Committee which was due to meet in the upcoming month. Atif had identied the alignment of employees with organisational values and growth as an issue which merited special attention. As the size of the organisation had grown, the challenge of aligning individual and organisational values was only natural. This related to the ongoing need of instilling in employees a clear understanding of the main principles of Akhuwat. Next morning, Atif called a meeting of his HR team, comprising ten members, to brainstorm on this issue. They reviewed and organised the past data (Table 1) for a macro- view of the organisation's growth: Table 1. Amount disbursed and number of employees in Akhuwat Micronance 2005-2006 2017-2018 Amount 111.02 million 66.58 billion Disbursed (PKR) Number 4,427 em 10 ees 1 Dr Jawad Syed and Dr F aiza Ali (Suleman Dawood School of Business, Lahore University of Management Sciences) wrote this case as a basis for class discussion rather than to serve as an endorsement, source of primary data, or illustration of effective or ineffective management. The case does not necessarily represent the views of the studied organisation. A few days later, Atif met with Chief Financial Ofcer (CFO) and Chief Credit Ofcer (CCO) to contemplate on HR's response to these issues at Akhuwat. After an exhaustive 3- hour session, it was agreed that alignment of growth and values needed to be addressed through multiple interventions, addressing any gaps in terms of values and performance and revisiting the processes for dissemination of Akhuwat's core values and principles. When Akhuwat started as a small microfmance organisation with 47 employees, most of them from the personal circle of the founder chairman, it was easy to manage due to the small size of the organisation. However, with the enormous growth of branches and employees over the years, the issues of employees' alignment with organisational values had become rather challenging. Organisation's background In 2001, the idea of Akhuwat was presented by Dr Amj ad Saqib to a group of friends at the Lahore Gymkhana Club. During the conversation, the issue of excessive interest rates on microfmance programmes was critically discussed. The idea of initiating an interest-free microfmance programme to alleviate poverty was brought forth as a challenge. The friends pledged their support and Dr Saqib, who had three years of experience in the micronance industry, offered to design, organise and implement an interest-free programme. The programme would be the rst of its kind in the country. The rst loan of PKR 10,000 was given to a widow who was striving to earn a decent living through honourable means. Instead of looking for charity, she was only interested in a loan. By using and returning that loan within months, she reinforced the founders' trust in poor people. This initial success led to further donations. This was the genesis of Akhuwat with the initial circle of friends forming the rst Board of Governors and Dr Saqib serving as its Chairman and Executive Director. From that point, the organisation continued to grow with donations far exceeding initial expectations. By 2003, the total donations had reached PKR 1.5 million with a 100% recovery rate. At that stage, the organisation was formally registered under the Societies Registration Act of 1860. The rst branch was opened at Township, Lahore. With the passage of time, Akhuwat opened more branches within and outside Lahore, diversied its loan products, and expanded the clientele. As a result, the message and outreach of Akhuwat began to spread and several new donors generously contributed. As a rule, costs were kept very low owing to minimal application fee and operational costs (Table 2). Extreme simplicity in operational activities, simple ofces, use of mosques and other religious places for meetings, and high levels of volunteerism in the workforce helped in this regard. Akhuwat had a unique business model aimed to provide small interest-free loans in the spirit of Islamic notion of akhuwat or mawakhat (fraternity). It may be noted that interest is strictly forbidden (haram) in Islamic religion. The organisation used charitable donations to establish its lending base. It gathered donations from the community based on Islamic charity appeals (such as zakat) and philanthropy.2 The organisation offered a range of products. Two of the most popular products included: (a) Family Enterprise Loan (8590 % the product portfolio) offered for the establishment of a new business or the expansion of an existing one. (Range: PKR 10,000 to Rs.50,000; Duration: 10 36 months), and (b) Agriculture Loan (5-10% of the product portfolio), offered to small farmers for purchasing agriculture inputs and meeting ancillary expenses (Range: PKR 10,000 to PKR 50,000; Duration: 4-8 months). 2 https ://www.akhuwat_org.pk/timclines/ w Table 2. Cost structure at Akhuwat Interest Zero Loan Processing Fee Zero Profit Zero Application Fee PKR 200 per application Mutual Support Fund 1% of loan amount (voluntary) Organisational structure Akhuwat was governed by a Board of Directors consisting of philanthropists, civil servants and businessmen. The Board met quarterly to review operations and provide advice. In additional to internal governance, the Board was also responsible for marketing services and mobilisation of funds for loans. An Executive Committee comprising three members met on a monthly basis to review important administrative and operational issues. Dr Amjad Saqib was the Executive Director of Akhuwat. The organisational structure mainly consisted of four main departments, which included Administration and Human Resources Department, Credit Department, Finance and Accounts Department, and Internal Audit Department (Figure 1) '. Information Technology department was managed by its own departmental head who reported to Chief Operating Officer. All the departmental heads except the Head of Internal Audit reported to Chief Operating Officer. Chief Operating Officer reported to Executive Director. Dr Saqib and all the Board members worked on an honorary basis and had no financial interests in the organisation. Figure 1. Akhuwat's organogram chief Admin chief Credit Chief Financial ST.Accounts Someary IT Manager Manmin HR Manager Development Manager Manager ayrol Manag Asst Adr Regional test. Account IT Executives Admin Officers HR Officers Software Marketing Loan Officers Accountants The head office in Lahore was responsible for managing, planning, and organising different activities and projects, which were divided among different regions. The Chief Credit Officer led a team of regional managers who were responsible for their respective regions. A Regional Manager led 7-10 Area Managers who in turn were in charge of 5-7 Branch Managers. A typical Branch Manager was responsible for 4-6 Unit Managers. Some areas had a steering committee, consisting of 8-10 prominent individuals living in that area and two http://www.akhuwat.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Akhuwat-Islamic-Microfinance.pdf https://www.akhuwat.org.pk/about-us-2/representatives from Akhuwat, generally the Area and the Branch Managers. The steering committee was responsible for overseeing the branch and mobilising funds. Key regions of the organisation included the following: Central Region-1 (Township), Central Region-2 (Sheikhupura), Gujranwala, Jaranwala, Thelum, Chakwal, Faisalabad, Multan, Jahania, DG Khan, North-1 (Rawalpindi), North-2 (Abbottabad), North-3 (Nowshera), Gilgit, FATA, Karachi. Employee profile As of May 2019, Akhuwat had 817 branches across Pakistan. The country was divided into 23 regions which were managed by regional managers. Within each region, there were several branches and units. The organisation had 6794 employees out of which 2721 were credit officers (unit managers). New employees had to undergo an initial 6 month of internship after which they were considered for formal engagement. From 9am to 2pm, the unit officers were expected to work in their offices and from 2-5pm, they were expected to be on field visits. Most of the employees were Credit Officers, typically with education up to 8th grade (middle) or 10th grade. They had basic literacy in Urdu and Mathematics, with some understanding of English. At the time of staffing, they were hired on necessity based voluntary compensation. Dr Saqib described that Akhuwat was a blend of volunteerism and necessary compensation. Qualification requirements were flexible due to less competitive package. Staff commitment to the mission was needed in order to forego alternative, more lucrative external employment opportunities. Employees were expected to have at least some knowledge of Akhuwat's values and history. Each new employee was given books in Urdu written by Dr Saqib describing the fundamental values and evolution of Akhuwat and its services to the society. Employees at Akhuwat considered the founder-chairman as the primary source of guidance and visualised him as their mentor. They drew inspiration from him for performing their assigned duties and understood that their work, however small it might be, was contributing to the greater good Given the low academic qualification and minimal professional experience of most employees at unit and branch levels, the organisation mostly comprised individuals who found less charm in financial incentives in comparison to self-actualising high commitment to the organisation's mission and values. The philanthropic bond between the organisation and its volunteers, especially the management cadre, seemed to be too strong a commitment with a cause to consider external market opportunities for financial incentives. However, in some cases, the decision to work with Akhuwat was made due to the lack of employment choices. The organisation's aspirations of expanding and also spreading into multiple sectors such as microfinance and education depended on the capabilities of its existing employees. The issue of employees' qualifications and capabilities was complicated by the fact that there was very little lateral hiring in the organisation. Most of the branch managers and regional managers were, in the start, hired as credit officers and later promoted to senior levels. There was a chain of progression from internship to credit officer to branch manager to area manager to regional manager. Akhuwat's typical workforce regularly worked extra hours, including weekends, without extra compensation. Staff while paid for 40 hours a week also volunteered extra time for mobilising for the cause, which could span an entire day in the field. According to Dr Saqib, this was an evidence of voluntary spirit. One possible explanation for this voluntary spirit was the religious emphasis on serving others, fi sabeelillah (in the way of Allah). The compensation https://www.akhuwat.org.pketwork/5 was thus expected in the Hereafter. Dr Saqib and other senior managers often reminded the field employees that their compensation was much more than monetary, it was in the form of prayers they received from the needy and the underprivileged people. Mission, vision and values In terms of its philosophy, Akhuwat derived its name from 'mawakhat' or brotherhood, the earliest example of which could be traced back to the communal fraternity formed in 622 AD by the Ansar (helpers, the citizens of Medina) in support of the Muhajireen (migrants), who had migrated from Mecca to Medina to escape persecution. Inspired by this spirit, which induced the citizens of Medina to share half of their wealth with the migrants, Akhuwat sought to invoke this concept through its mission and operations to develop a system based on mutual support and sacrifice. To this end, the organisation used microfinance, with no interest, as a powerful tool to eliminate poverty. Akhuwat sought to base its operations on the Islamic principle of Qarz-e-Hasan which entailed helping someone in need with interest free loans, a practice favoured over charity and doles. The organisation also incorporated some of the best practices and lessons learnt from conventional microfinance movements from across the globe. For example, application fee was kept very low (PKR 200) and efforts were made to minimise the operational costs. Akhuwat's vision was to develop: "A poverty free society built on the principles of compassion and equity". It stated its mission as "To alleviate poverty by empowering socially and economically marginalised families through interest free microfinance and by harnessing entrepreneurial potential, capacity building and social guidance." The organisation identified the following six objectives for itself: 1. To provide interest free microfinance services to poor families enabling them to become self-reliant. 2. To promote Qarz-e-Hasan [interest free loan] as a viable model and a broad-based solution for poverty alleviation. 3. To provide social guidance, capacity building and entrepreneurial training. 4. To institutionalise the spirit of brotherhood, compassion, and volunteerism. 5. To transform Akhuwat borrowers into donors. 6. To make Akhuwat a sustainable, growth-oriented and replicable organisation. Moreover, the organisation identified the following five core principles or values?: 1. Interest-free microcredit: Akhuwat provided interest free loans to the economically poor so that they could acquire a sustainable livelihood. The organisation also provided the skills and support they needed to actualise their full potential and abilities. 2. Use of religious places: The Akhuwat Model institutionalised the use of local religious places, for example mosque, temples and churches, as centres for loan disbursements and avenues for community participation 3. Transforming borrowers into donors: The organisation encouraged its borrowers to donate not necessarily to Akhuwat's programme in order to "help build their society once the borrowers themselves have gained enough economic stability". However, such donations were neither compulsory nor had any bearing on the borrower's credit profile. Originally the Member Donation Programme [MDP] was not part of Akhuwat's operation. 6 http://www.akhuwat.org.pk 7 http://www.akhuwat.org.pk/objectives.asp https://www.akhuwat.org.pk/core-principles/However, the idea evolved after a borrower, who had successfully managed to secure a sustainable livelihood for himself, insisted on contributing to Akhuwat so that the organisation could continue to help others like him. 4. Spirit of volunteerism: Akhuwat presented its idea as a social contract, a pact between the privileged and the underprivileged, a duty of those who have resources towards those who do not. The organisation gave special importance to the spirit of volunteerism that its managers and team members exhibited and linked it with exemplary organisational performance and growth. 5. Non-discrimination: The organisation promoted an inclusive society, and practiced nondiscrimination on the basis of caste, colour, creed, gender, political afliation and faith. It described itself as a pro-poor organisation. Given that mosques across the country were almost exclusively a male domain, there was a greater possibility that men were at an advantage in terms of access. The organisation was in principle committed to gender equality and sought to address such concerns through its product of Family Loan. Although the female share in overall borrowers had increased over the last few years, it still represented only 42% percent, which was lower than the national average of above 60 percent in the micronance sector. Akhuwat also practiced non-discrimination on the basis of religious beliefs. According to local demographics, loans were also disbursed through churches or Hindu temples. The presence of non-Muslim clients and non-Muslim staff members indicated an inclusive approach. Akhuwat's ofces generally displayed its mission and core principles with an aim to reinforce the organisation's raison d'tre. Employees were generally cognisant of the organisation's core values and understood what they were working towards. Dr Saqib considered the spirit of volunteerism as one of Akhuwat's greatest assets. Employee training Akhuwat had an operations manual covering the complete lifecycle of credit. The manual elaborated the steps involving the processing of a loan application and performing social and economic appraisals. The immersion training of new hires included reading and comprehending Nishane Manzil (Reaching the destination, Akhuwat's credo), Akhuwat Ka Safar (Akhuwat's journey), Dasht-e-Zulmat Mein Aik Diya (A lamp in a dark desert) and some videos. Such training was carried out in a structured and planned way. The rst-line recruits were offered 15 days initial training to evaluate whether the candidate was worthy of full time employment or not. After the initial training and ltration, the recruits were brought to Lahore for a further 7 days training. This tier of training mainly comprised of lectures and individual group activities. Several of these sessions were led by Dr Saqib himself. After the second tier of training in Lahore, the recruits would spend 2-3 months doing eld work. Thus, after about a multi-tier 6 months training, these candidates would be evaluated for the position of unit ofcer. Their subsequent promotion to Branch Manager would depend on their competencies and organisational growth. A key challenge facing Akhuwat was how to train and develop those recruits who had no previous experience of working in an ofce and had little knowledge of Akhuwat's operations and values. To use a metaphor, Dr Saqib told new recruits that they must treat their ofce as an extension of their local religious space, by treating it with respect, keeping it clean, and refrain from smoking. In addition to ordinary public, Akhuwat also hired students from Islamic madrassas (reliogus schools). The trainers use metaphors and adages that were already known to many new recruits such as the emphasis on virtues and goodness. Many madrassa students were V already familiar with the concept of mawakhat. In this way, by translating the concepts they already knew into practice, the basic training became much easier and effective. For the paid staff, the positions were well defined and minimum criteria was set for each position. Employees also availed health and life takaful, a co-operative system of reimbursement or repayment in case of loss, an Islamic sharia compliant alternative to conventional insurance. In addition to paid staff, the organisation also provided opportunity for voluntary or unpaid work. Volunteers were encouraged at all levels irrespective of age, gender, ethnicity or caste. To spread its message and brand of virtue-based development, Akhuwat also offered a 6-week fellowship through its institute, Parwaaz, to the general public and students for their self-development and to spread Akhuwat's values. The organisation was also hosted philanthropic and scholarly debates and dialogues, charitable programmes, and awareness sessions, e.g., the programmes highlighting the importance of mental health to eliminate poverty. The organisation also encouraged other individuals and organisations to replicate the Akhuwat model, with Akhuwat training the staff and assisting in the initial setup. Such replications were encouraged to enable local successes and for everyone to benefit from Akhuwat's expertise. The infrastructure of values Akhuwat's offices were small and simple. A typical office had no chairs or office desks. Employees and borrowers both sat on the floor, often on ordinary cushions or pillows facing a low-rise wooden platform, which was used as a desk (Figure 2). At times, such desks were shared by more than one employee. Since most activities such as pre-disbursement meetings and actual disbursement ceremonies were carried out in mosques or other religious centres, the organisation had little additional costs in conducting such activities. Figure 2. A Typical Akhuwat Office AKHUWAT Urdu text's translation: Akhuwat, an organisation for interest-free small loans, Gharibabad Branch, Peshawar https://www.facebook.com/AkhuwatOfficialWithin Akhuwat's publications and infrastructure, there were frequent references to and reinforcement of the organisation's mission and core values. In each branch office, there was a copy of 'Akhuwat Ka Safar', which described Akhuwat's journey in Dr Saqib's own words. For example, on pp.23-24, he described how he started the first operational office in a small cabin of Punjab Rural Support Programme, and how he and his friends started this work in a slum area behind Lahore General Hospital. On p.27, Dr Saqib referred to the mawakhat event in Medina. The presence of this book in each branch indicated an emphasis on Akhuwat's history, humble beginnings, core values and Islamic emphasis on interest-free loans. The organisational values were also displayed and reinforced in the shape of notices and posters in various offices. An example of one such message, painted on a main wall in Akhuwat's head office, is provided in Figure 3. A loose translation of this text is as follows: "It is everyone's fundamental right to lead a respectable and fulfilling life. Akhuwat's aim is to develop a fraternity-based society where men and women have equal opportunities to progress, and there is no discrimination on the basis of colour, creed, race, faith or religion. In the light of Prophet Muhammad's (PBUH) teachings, we promote values of sharing, sacrifice and tolerance. We understand that success in life is inherent in obedience to Allah and service to humanity. While we are guided by our religion and traditions, our message is for the entire humanity." Figure 3. Akhuwat's purpose displayed on a wall in the head office Akhuwat relied heavily on the use of mosques and other religious place to conduct its events. Each month, the borrowers set to receive loans were asked to gather inside a mosque (or a church if the majority of the recipients was Christian). Figure 4 shows a typical disbursement event at a mosque and Figure 5 shows another event at a church. Such events not only acted as social collateral but also provided sanctity and spirituality to the process. Borrowers believed it their responsibility to work hard and return loan instalments on time. According to Dr Saqib, the use of places of worship for such events also led to other positive outcomes, "We have conducted many disbursements with Muslims, Christians and people from other religions sitting together in a mosque or church. This has led to an increase in inter-faith harmony and fall in sectarianism as people started to know each other's faith."Figure 4. A loan disbursement event at a local shrine in Lahore (2014) 10 Figure 5. A disbursement event at a local church (2015)11 A Clocked Pakistan LOVE, RESPECT AND DIGNITY @PNCBA Akhuwat's leaders and the organisation's ideology Dr Saqib explained that the evolution of human resources in Akhuwat was unique. In the first two years, he was the one-man human resource of the company, who had to serve as a planner and implementer. Along with a group of five volunteers, he worked on processes and procedures based on their own insights and experience. All of the initial manuals and other documents were designed by Dr Saqib and his small team. Dr Saqib recalled that his own boss in a previous employment, Mr Shoiab Sultan, a famous development professional and founder of the Agha Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP), taught him that developing and replicating people was more important than achieving targets. Keeping that lesson in mind, Dr Saqib's focus was on replicating people with same vision and values. He discussed how he transferred his vision and values to his team members. He trained the initial team of 30-40 people to 'replicate' these values. https://twitter.com/Akhuwat https://twitter.com/Akhuwat10 The key norms that Dr Saqib tried to implement at Akhuwat were humility and accessibility. His mobile phone number was widely shared with his staff so that they could contact him easily. Through frequent interactions, he knew hundreds of his employees by name. Dr Saqib stated that managers and workers in Akhuwat's different branches and ofces across Pakistan had the same vision and values although their language and expression might vary. He Visited eld sites on a regular basis and also addressed them through telephone as a refresher of Akhuwat's values and expectations. In terms of measuring employees' commitment to core organisational values, Dr Saqib explained that he generally hired lowqualied employees at the grassroots level, even as low as those who had passed only 8"1 grade. For the purpose of eld work, the organisation preferred to give opportunity to those with minimum qualication who were expected to work with dedication and commitment. The organisation preferred to hire someone who had not been employed previously. The idea was that the new employee should not be familiar and tolerant of any unethical practices in organisations, something that was much harder to unlearn. Dr Saqib acknowledged that getting good employees was a key challenge facing Akhuwat. He noted that ethical values were the most important thing in employees and it was not easy to fmd people with high ethical standards. Dr Saqib noted that religion was something held in respect by people. Thus, it was only natural to use religious values to promote positive ideas and ethical principles in the workplace, consistent with Islamic ethics. He considered it an opportunity for other development experts and NGOs to use this model and draw inspiration from religion. Dr Saqib also talked about the non-discriminatory nature of the organisation. For example, the Akhuwat ofce in Tharparkar area in Sindh was called 'Bhagwan Bank', based in a Hindu Temple. (Bhagwan is an epithet for deity in Hindu religion.) This was to reflect the religious values and sentiments of the local population in that area. The organisation also provided employment to transgender persons. At the Akhuwat head ofce in Lahore, there was a charity clothes department (Clothes Bank) where several transgender individuals were employed. Within other senior leaders, there was a clear emphasis on Akhuwat's mission and ideology. For example, Mr Saleem Ranjha, Akhuwat's founding codirector, explained that: \"The philosophy of Akhuwat that you hear from someone in Khokrapar or in Mithhi [in Sindh province], the same rules, the same principles, the same thinking you will get to hear in Sust [in Gilgit-Baltistan]. Moreover, all the growth that we have gone through is organic. It's not that one ne morning we decided to go from 50 to 100 branches, the headquarter did not create the 50 new branches, the existing 50 did.\" The multi-faith and inclusive nature of Akhwuat's operations was a part of the senior leadership's discourse. Mr Ranjha linked inclusion to the spirit of volunteerism. \"We have to operate through the temple, mosque or church... we have to create volunteerism. We have to give, not take. I do not think of what I could take from Akhuwat, I think of what I can give to the society through Akhuwat.\" The organisation expected employees to commit to its core values. While Mr Ranjha recognised that some employees might not be getting a market competitive salary, in his View, their commitment to the cause was what kept them engaged. 11 \"When I look at Akhuwat's employees, at times I feel like their commitment to Akhuwat is higher than my own commitment. For example, in terms of clarity of purpose, they know what they want to do. Their sense of volunteerism is probably better than mine. While Akhuwat is paying them, they are working 16 hours instead of 8 without any extra payment. For the same work, if they receive an offer from elsewhere with a salary of say 100,000, while they get 50,000 here, they mostly still do not quit. They are very clear. They have a sense of purpose, which is larger than life and dear to them. That is something really interesting.\" There was also special attention to keeping the operational costs low in order to maintaining viability of the entire project. For example, there was no provision for refreshments expenses in the company's budget. This point was thus explained by Mr Ranjha. \"Akhuwat introduced a principle that we would not even drink water from the borrower's house. What happens is that the game of exploitation begins with water and tea. You have water, then comes a soft drink, then comes tea. So, we decided, probably in the very rst year, that the Akhuwat's representative will not even drink water from the borrower's house. The interesting part is, even in our ofces, there is no refreshment other than plain water. If someone does offer tea, it is on the employee himself/herself. The bill goes to the employee's account. I wouldn't offer you tea in the head ofce, I would offer it elsewhere and then I would pay the bill.\" While the internship programme was looked after by the HR at the organisation's Head Ofce, Ms. Fatima Rasheed, Director of Parwaaz, supervised the fellowship programme at Parwaaz (the new name of AISEM: Akhuwat Institute of Social Enterprise & Management). Ms Fatima Rasheed explained the importance of such engagement: \"For Akhuwat, the alleviation of poverty is a moral activity to be driven by compassion and guided by principles of justice. This is what we hope to nurture in our students. Through the fellowship, our aim is to cultivate a community of creative entrepreneurs and moral leaders committed to making a difference.\" Akhuwat's commitment to philanthropy and social well-being also led it to venture into projects other than micronance. One such project was the Akhuwat College in Lahore. Mr Ranjha explained how values of integrity were being inculcated in the students at the college. \"When you go to Akhuwat College in Kamaha, Lahore, there are 140 children, from 40 different districts from across the country, right from Khaplu, down to Gwadar. And they all have come after doing their matriculation (10th grade). One interesting experience, which was an eye opener for me, was setting up of an unmanned shop at the college. That is a shop, a canteen, you go, you buy, there is no one there, and there is no camera. And there is 100% right payment! Think about these kids graduating from this college, learning and exhibiting integrity using an unmanned shop, what would they be ten years down the road?\" In addition to training and developing such values in students and interns, there was also a systematic emphasis on moulding new and existing employees into organisational values. Mr Atif Tufail (CHRO) thus explained the acculturation and training process: 12 \"We have systems and procedures in place to inculcate Akhuwat's values and ideology in our employees. Each employee is given a copy of 'Nishan-e-Manzil' and 'Akhuwat Ka Safar'. We also meet our unit and branch managers and their family members or parents to educate them about our values and thank them for their support. We conduct quizzes of all employees to check their understanding of Nishane-Manzil and also ask them to give presentations in the presence of senior management on our core values. In this way, senior management ensures that all employees are aware of the history, values, strategy and principles of Akhuwat.\" This ongoing process was executed in a structured way under the supervision of Mr Atif Tufail. All new employees were asked to write Nishan-e-Manzil with their own hands and submit a hard copy to Mr Atif Tufail for placement in their respective employee les. The new hires also signed an Iqrar Nama (declaration) afrming that they had read and understood Nishan-eManzil and Akhuwat ka Safar. This process was a part of immersion training and its reinforcement continuously aimed at alignment with organisational values and growth. Akhuwat's Chief Financial Ofcer (CFO), Mr Ahsan Billah, told that he previously used to work in a bank where interest was involved in almost all products. He did not like the job due to religious reasons, and he had always thought of bringing a change in the nancial system in a socially responsible manner. He said that Akhuwat gave him the platform to do something for the deserving people. Mr Ahsan stated that at Akhuwat, there was emphasis on transparency and integrity in all matters related to money. For example, there was only one document for audit. While he acknowledged that the salary at Akhuwat was lower as compared to other organisations, he referred to the Islamic notion of 'barkat', i.e., abundance in austerity, and said that he was always able to save money from his monthly salary. He mentioned that working in Akhuwat had provided him with peace of mind and that he could sleep well at night. Organisation's growth Since its inception, Akhuwat had grown exponentially in terms of its loan portfolio and branches (Tables 3 and 4). In 2010, it experienced rapid expansion after an enormous credit injection from the government of the Punjab province, and also some funding by the federal government of Pakistan. The funding was largely provided as a part of selfemployment scheme and agricultural loans offered by the government. Its active loan portfolio and number of branches grew enormously due to this injection. This transition warranted considerable changes in the human resources and performance management systems, particularly because historically most of its activities and tasks were done informally. There were specic disbursement targets for each region and unit, and a relatively recent development was that the progress was regularly monitored through an app available on the intranet. Akhuwat had disbursed more than PKR 80 billion to 3.24 million beneciaries by 28 Feb 2019. Table 3. Progress Report (February 28, 2019)12 Progress Indicator Total Total Benetin Families 3.24 million Total loans disbursed Males 1.89 million 1.35 million 80.085 billion 99.94% Total loans disbursed Females Amount Disbursed PKR Percenta e Recove Active Loans 1.002 million Outstandin Loan Portfolio PKR 17.16 billion Number of Branches 81 1 '2 https://www.akhuwat.org.pk/ycarwiseprogrcss-report/ 13 Table 4. Organisational Performance: Year Wise Progress Report at a Glance13 Indicators Year No. of loans Amount Disbursed % of recovery No. of Employees 2001-2002 192 1.89 m 100% 3 2002-2003 282 2.79 m 99.90% 3 20032004 832 8.50 m 99.90% 12 20042005 3,124 31.81 m 99.90% 32 2005-2006 6,264 66.02 m 99.90% 50 20062007 8,674 89.93 m 99.80% 75 20072008 11,388 122.44 in 99.80% 76 2008-2009 13,821 164.23 m 99.80% 101 2009-2010 21,073 251.81 m 99.80% 186 20102011 34,194 418.2 m 99.80% 343 20112012 67,683 1.14b 99.83% 615 2012-2013 159,138 2.58 b 99.82% 869 2013-2014 234,883 4.05 b 99.85% 1549 20142015 367,798 7.31 b 99.92% 2013 20152016 496,458 11.21 b 99.92% 3497 2016-2017 619,396 16.58 b 99.96% 5693 2017-2018 731,302 99.93% Moving forward Dr Saqib believed that while short-term poverty could be alleviated by giving small loans, long-term poverty could be alleviated by educating people. He thought that microfinance was a tool, not the goal. While a small short-term loan could save someone from hunger, in the long term, education was the only possible route to empowerment. Accordingly, he had decided to expand the organisation to the education sector by establishing several colleges and a university. He sought to establish academic institutions where people could study on interest free student loans and return the money whenever they started earning. The students at some of the educational institutions established by Akhuwat were reminded that much like Akhuwat was investing in their education, once they were in a position to do so, they must help another deserving student realise his/her dreams. In the spirit of inclusion and positive action, at Akhuwat's colleges and university, there was a 20% quota from each province and administrative area, including Gilgit Baltistan, tribal areas and Azad Jammu and Kashmir to ensure that deserving candidates 'om all comers of Pakistan were selected. At these institutions, the diversity of students was evident in the shape of diversity of languages, ethnicities, and faiths. Through Akhuwat University, Dr Saqib wanted to create the next generation of leaders for Akhuwat and the society at large. Mr Atif Tufail, the CHRO, was hopeful that such future recruits would alleviate the challenges of aligning core values and organisational growth currently facing the organisation. 13 https ://WWW.akhuwat.org.pk/yearWiseprogressreport2/