Question: Base on the above information please answer the following question. (Please also tell me which part did you get the answer/ideas from) 1. How do

Base on the above information please answer the following question. (Please also tell me which part did you get the answer/ideas from)

Base on the above information please answer the following question. (Please also tell me which part did you get the answer/ideas from)

1. How do the 5 characteristics (not Tuckman's model) outlined reflect group development?

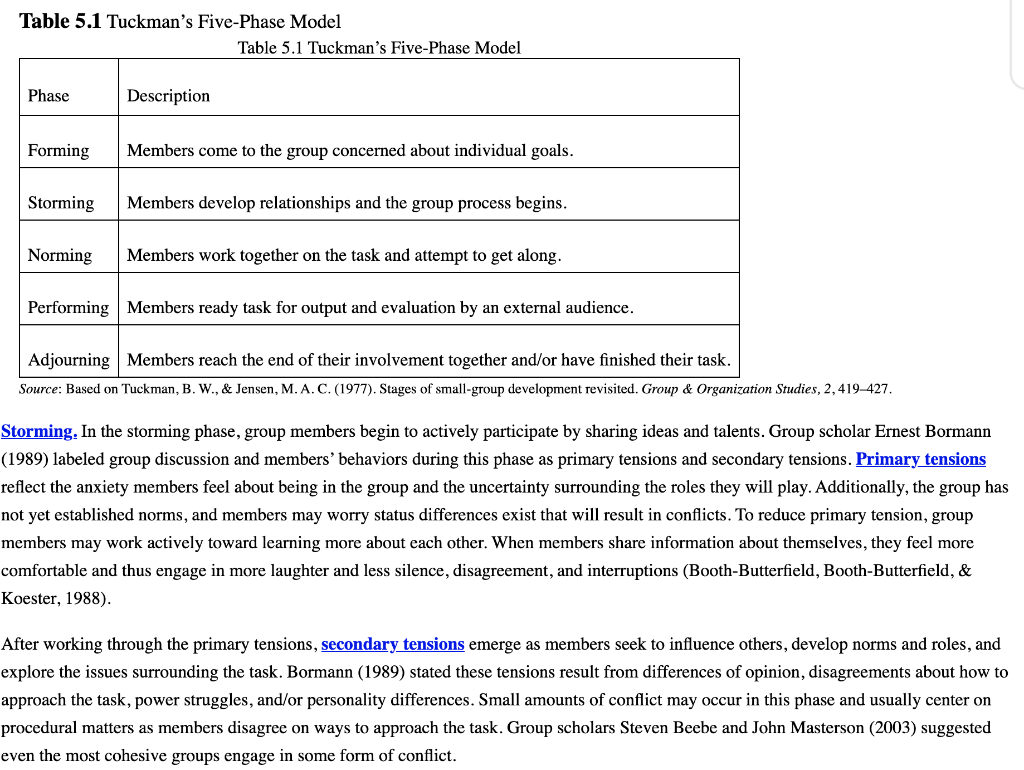

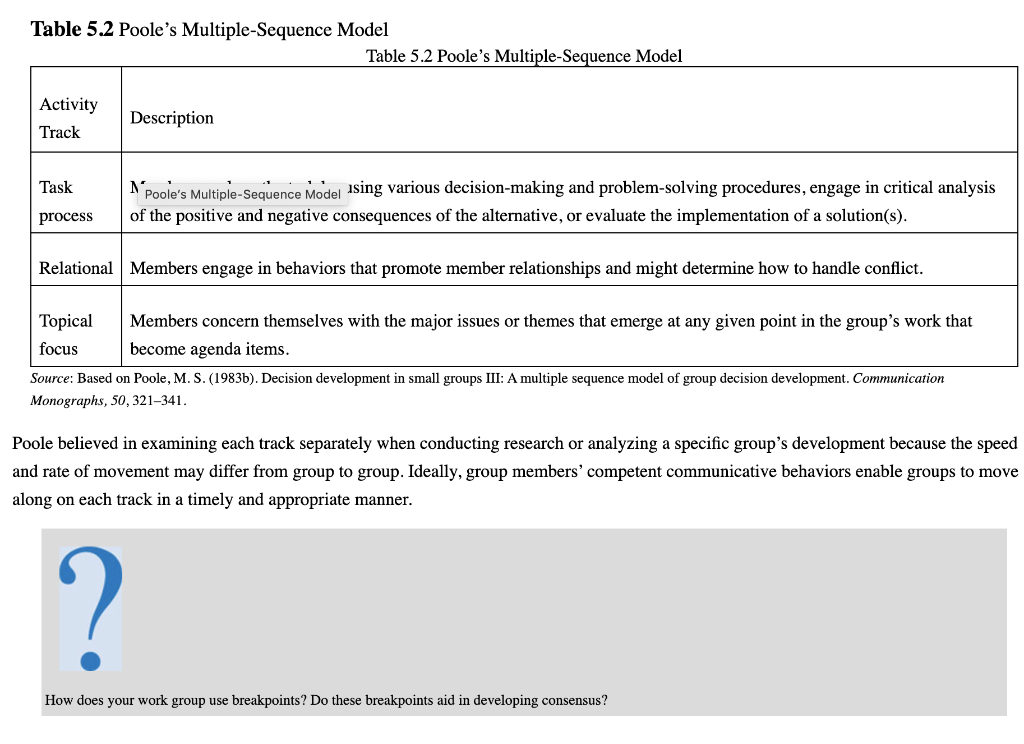

Group Development Two factors influence group development: group history and group maturity. History Group members build a history of working together, as well as the methods and motivation behind their move through group development. Communication scholar Thomas Socha (1997) suggested when we think about communication and group development, we should consider that communication changes not only across the life span of a specific group but also across the life span of each group to which we belong. As members of multiple groups throughout our lives, we bring ever-changing levels of expertise, cognitive abilities, and social skills to each group experience. Furthermore, even if we participate in groups facing different tasks or activities with people we know or have worked with before, the members still must redefine themselves as part of a new group with its own unique developmental process. Just as no two groups comprise the same mix of individuals or strive for the same task or goal, no two groups develop and move through the process of group work the same way. Lee Gardenswartz and Anita Rowe (1994) claimed the challenges of group work include the understanding that disparate people can come together to achieve work-related goals of varying complexity, importance, and impact" (p. 145). Successful groups just don't happen; instead they comprise the proper blend of human dynamics, abilities, and skills to confront and complete the task. Maturity Not only do groups develop a history; they also mature as they move toward goal achievement. Maturity, marked by the fact that all group members are task oriented and work cooperatively toward furthering the group goal (Bonney, 1974), refers to the ability and willingness a group possesses as it moves through the developmental process (Hersey, Blanchard, & Johnson, 2000). Ability describes a group's collective knowledge, skills, and experience whereas willingness refers to a group's collective motivation and confidence. When groups are mature (i.e., both able and willing), they are more active and more organized and do not need extensive encouragement to work on a task (Krayer & Fiechtner, 1984). In college classrooms, mature groups meet more often, express more satisfaction with the group experience, and perform better than immature groups (Krayer, 1988). Developmental Models Although several models of group development exist (Bales & Strodtbeck, 1951; Caple, 1978; Fisher, 1970; Near, 1978; Wheelan & Hochberger, 1996; Worchel, 1994), in this section we will examine three unique models of group development: Bruce Tuckman's five-phase model of group development, Connie Gersick's model of punctuated equilibrium, and Marshall Scott Poole's multiple-sequence model. Tuckman's Five-Phase Model Bruce Tuckman (1965) introduced a four-phase linear model of group development and then later added another phase (Tuckman & Jensen, 1977). Tuckman's five-phase model provides a popular contribution to understanding group development and the discussion process. The five phases, referred to as the forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning stages, cover group structure (i.e., relationship patterns) and task behavior (i.e., what the group is working on). Forming. In the forming phase, group members meet the group process with their own reasons for joining the group. According to Joann Keyton (1999), individuals face such issues as inclusion and dependency (e.g., "What ideas will the members like?" and "What will I be asked to do?). During this phase, no reason yet advises group members to completely trust each other. Group discussion takes on an exploratory nature as members try to find their place, confirm their perceptions about other members, and decide what they will agree to do. The discussion in this phase more than likely is superficial. Social politeness theory suggests when individuals join groups they operate under a norm of being polite to others. Remember, the members think not yet in terms of "we"; rather, they think in terms of "I. In this phase, members exhibit (not too strong, pushy, or abrasive) verbal and nonverbal behaviors. Because members are not committed to each other, they draw upon prior group experiences to determine if they will meet their expectations in the group. Table 5.1 Tuckman's Five-Phase Model Table 5.1 Tuckman's Five-Phase Model Phase Description Forming Members come to the group concerned about individual goals. Storming Members develop relationships and the group process begins. Norming Members work together on the task and attempt to get along. Performing Members ready task for output and evaluation by an external audience. Adjourning Members reach the end of their involvement together and/or have finished their task. Source: Based on Tuckman, B. W., & Jensen, M.A.C. (1977). Stages of small-group development revisited. Group & Organization Studies, 2,419-427. Storming. In the storming phase, group members begin to actively participate by sharing ideas and talents. Group scholar Ernest Bormann (1989) labeled group discussion and members' behaviors during this phase as primary tensions and secondary tensions. Primary tensions reflect the anxiety members feel about being in the group and the uncertainty surrounding the roles they will play. Additionally, the group has not yet established norms, and members may worry status differences exist that will result in conflicts. To reduce primary tension, group members may work actively toward learning more about each other. When members share information about themselves, they feel more comfortable and thus engage in more laughter and less silence, disagreement, and interruptions (Booth-Butterfield, Booth-Butterfield, & Koester, 1988). After working through the primary tensions, secondary tensions emerge as members seek to influence others, develop norms and roles, and explore the issues surrounding the task. Bormann (1989) stated these tensions result from differences of opinion, disagreements about how to approach the task, power struggles, and/or personality differences. Small amounts of conflict may occur in this phase and usually center on procedural matters as members disagree on ways to approach the task. Group scholars Steven Beebe and John Masterson (2003) suggested even the most cohesive groups engage in some form of conflict. Norming. In the norming phase, the group and its members work together on the task and attempt to get along. In this phase, trust begins to develop, and acceptance starts to emerge (Keyton, 1999). Tuckman believed this phase reflects group cohesiveness. Cohesive groups commit to working on the goal and task as a collective unita commitment sometimes referred to as the glue that holds the group together. Cohesiveness increases with group discussion that facilitates role taking and norm stabilizing. The degree of cohesiveness continues to build as the productivity of the group increases and the group achieves consensus on decisions it needs to make (Beebe & Masterson, 2003). At the same time, group members' trust, commitment to the group, and willingness to cooperate increases in this phase (Wheelan, Davidson, & Tilin, 2003). Conformity and deviance ca Tuckman's Five-Phase Model of cohesion (Pavitt & Curtis, 1994). Conformity occurs when a group member agrees with the group's decision because the majority of the group members agrees. Conformity succeeds when a group member conforms in beliefs as well as in behaviors (Pavitt & Curtis, 1994, p. 179)that is, the member supports the group decision, even though she might have chosen a different option. If the member cannot live with the decision but goes along with it anyway, conformity still occurs, but it then is considered unsuccessful. Deviance occurs when a group member disagrees with the group's decision, even though the majority of the group members, who may view this member as rebelling against the group's norms (Scheerhorn & Geist, 1997), agrees. Deviance proves positive when a member forces the group to rethink its discussion procedures, such as when a member plays the devil's advocate role. The movie 12 Angry Men provides a classic example of getting members to change their minds. A single juror refused to go along with the "guilty plea the majority wanted, and one by one, the lone juror convinced the other jurors to change their minds. On the other hand, deviance proves negative when a member refuses to listen to valid arguments or reason and holds on to his position. This stance creates a barrier to movement through the norming phase. A note of caution: Groups would be wise not to fall into the trap of thinking that because they are cohesive, they do not have to follow the steps to making good decisions based on rational thinking. They still must follow the principles surrounding sound decision making and problem solving, as discussed in Chapter 7. Performing. In the performing phase, the task is readied for output and evaluation by an external audience. Considered the stage at which members produce the most work (Chidambaram & Bostrom, 1996), members focus their energy on task accomplishment and goal achievement (Wheelan et al., 2003). At this point, trust should be established so the group will succeed in goal achievement to the best of members' abilities. Joann Keyton (1999) suggested during the performing phase, group members are so tightly integrated with the team they find it difficult to distinguish themselves from the group" (p. 362). The established relationship structure of the group allows for solving of interpersonal conflicts, and constructive attempts are made to complete the task (Pavitt & Curtis, 1994). Lee Gardenswartz and Anita Rowe (1994) described the performing phase in group life as growth from infancy (i.e., forming phase) to maturity (i.e., performing phase), manifested by group pride in accomplishments and a "willingness to do what it takes to keep doing the job (p. 196). Adjourning. In the adjourning phase, the group reaches the end of its involvement. Sometimes the adjourning phase depends on the time frame given to the group; at other times, the adjourning phase simply occurs when the group finishes its task. Regardless of how the group arrives at this phase, group members may express mixed feelings. Some group members may feel happy the group has ended, some may mourn the loss of being involved in an interesting task and forming interpersonal relationships, and some may attempt to keep the group intact (Lewis, 1978; Rose, 1989). Lucinda Sinclair-James and Cynthia Stohl (1997) stated cohesive group endings are less traumatic for members if they expect to see each other or work together again. Members who like each other will stay in touch through e-mail, telephone, or other forms of communication. Thus, when the group adjourns, the socioemotional dimension changes, and the relationships among group members move to different levels of intimacy. Thelmon'o five nhace model of group development appeals to many due to its easy-to-identify-with sequential nature. Because many college Gersick's Punctuated Equilibrium Model classroom groups progress through the five phases (Runkel, Lawrence, Oldfield, Rider, & Clark, 1971), you likely can identify how this model surfaced in your previous classroom group experiences. Gersick's Punctuated Equilibrium Model Not convinced that all groups develop in a sequential manner, Connie Gersick (1988) developed a model of group development to address this position. In Gersick's punctuated equilibrium model, she asserted that groups progress through a period of inertia punctuated by a period of concentrated change (Chidambaram & Bostrom, 1996). In her model, group development occurs around the defining characteristic of time. Unlike sequential models of group development, Gersick argued that groups follow temporal periods of development she labeled as phases. According to Gersick (1988), group development starts with the first meeting of the group members. During this meeting, members set the precedent for how the group will approach task accomplishment. Group members' behaviors during this initial meeting implicitly guide the group's behavior for an indefinite amount of time, labeled phase one, during which little work is accomplished (Arrow, Poole, Henry, Wheelan, & Moreland, 2004). Rather, group members attempt to make sense of the task in light of their own experiences, viewpoints, and biases. They spend time attempting to diagnose the issue rather than trying to make a decision or solve a problem. Phase one lasts until the group approaches the midpoint of its allotted time to complete the task (Gersick, 1989). This midpoint, which Gersick labeled as transition, occurs when the group members realize they have used (or wasted, depending on their point of view) half of their time and now must determine how to accomplish the task. The transition, considered the group's "wake-up call, results in a sudden burst of activity devoted to the task (Gersick, 1989). In the case study, for example, Chad references a transition when discussing how the roommates planned their spring break trip the year before. At the transition point, members engage in a variety of behaviors: They drop old work patterns and habits, make an effort to start working more diligently, may or may not adopt new perspectives, and may or may not contact a stakeholder to determine whether they are proceeding in the right direction. (A stakeholder is a person external to the group who has a vested interest in the task.) Most importantly, they realize they need to seriously focus on completing the task, and this transition provides a basis for their work pattern in phase two (Gersick, 1988, 1989). Once the group experiences its transition, its members enter phase two. Unlike in phase one, group members accomplish much more work in phase two (Arrow et al., 2004), although they lack the urgency to finish their task. Not until the final group meeting, or what Gersick (1989) labeled as completion, must the group absolutely finish the task. During this time, group members put the finishing touches on their task, hypothesize about how outsiders will view their task, and express their feelings about the task and each other (Gersick, 1988). Gersick's Punctuated Equilibrium Model "Ethically Speaking: How acceptable is it for group members to work less diligently and wait for the midpoint transition to occur before mustering energy to finish the task? How do these types of behaviors affect productivity?" Although Gersick's model of punctuated equilibrium hasn't received as much attention from researchers as Tuckman's five-phase model of group development, Gersicks model, excitingly, explains why so many groups tend to wait until the last minute to finish a task. One important point to consider: Although Gersick's model seems to imply that group members avoid working on the task, this is not true. Rather, members work more diligently at the transition and completion points than they do during phases one and two. Poole's Multiple-Sequence Model Marshall Scott Poole (1981, 1983a, 1983b), a communication professor at the University of Illinois, developed another exciting model of group development, derived from the traditional phase model approach. Poole asserted groups do not always follow a rigid, phase-like approach when accomplishing a group task. Rather, he believed groups engage in three types of activity tracks that do not necessarily follow in a logical sequence. As described in Table 5.2, these three activity tracks include task process activities, relational activities, and topical focus. According to Poole, in an ideal group experience, the group will move forward on all three tracks to successfully complete its goals. At any point, a group will alternate among the three activity tracks. Switching from one activity track to another, known as a breakpoint (Poole & Roth, 1989), helps the group develop consensus (Fisher & Stutman, 1987). Poole (1983b) identified three breakpoints a group may use: normal, delay, and disruption. A normal breakpoint occurs when a group shifts focus or examines another aspect of a task. This breakpoint does not disrupt or impede task accomplishment. A delay breakpoint occurs when a group decides to reexamine a position or needs to repeat some part of a task, that is, when the group must adapt to a new contingency or focus strongly on comprehending the issue (Poole & Doelger, 1986). A disruption breakpoint occurs when conflict forces the group to stop working or failure forces the group to reevaluate its position. Whenever a breakpoint occurs, group members need to be flexible enough to address the breakpoint and then get back on track. In the case study, which breakpoint do the roommates use? Table 5.2 Poole's Multiple-Sequence Model Table 5.2 Poole's Multiple-Sequence Model Activity Track Description Task N Poole's Multiple-Sequence Model asing various decision-making and problem-solving procedures, engage in critical analysis of the positive and negative consequences of the alternative, or evaluate the implementation of a solution(s). process Relational Members engage in behaviors that promote member relationships and might determine how to handle conflict. Topical Members concern themselves with the major issues or themes that emerge at any given point in the group's work that focus become agenda items. Source: Based on Poole, M. S. (1983b). Decision development in small groups III: A multiple sequence model of group decision development. Communication Monographs, 50, 321-341. Poole believed in examining each track separately when conducting research or analyzing a specific group's development because the speed and rate of movement may differ from group to group. Ideally, group members' competent communicative behaviors enable groups to move along on each track in a timely and appropriate manner. ? How does your work group use breakpoints? Do these breakpoints aid in developing consensus? Characteristics of Group Development Regardless of the developmental path a group takes, five characteristics, as detailed in question form below, reflect group development (Chidambaram & Bostrom, 1996): 1. How cohesive is the group? Cohesion experts Albert Carron and Lawrence Brawley (2000) proposed that in any group, members will develop task cohesion (needed for group performance) and social cohesion (needed for member relationships) but not at the same rate or with the same intensity. Cohesion also may develop as a result of pride in group membership (Street & Anthony, 1997). Carron and Brawley asserted as a group moves through any developmental process (i.e., stage, phase, track), the cohesiveness that accompanies the group's developmCharacteristics of Group Development stage, phase, or track at which the group is located or engaged. 2. How does the group turule tunjuur: ml Chapiti u, you will learn more about conflict and how to handle conflict in a small group. One important consideration in handling conflict involves recognizing that conflict, inherent in any group's developmental process (Fisher, 1970), should not be taken personally. Group communication expert Roger Pace (1990) found that depersonalizing conflict is essential for effective group conflict management. Depersonalizing conflict occurs when group members recognize that conflict forms part of the small group process and thus do not attribute conflict to a specific group member. When group members depersonalize conflict, they report greater levels of cohesion and consensus (Pace, 1990). Photo 5.3 Group members should recognize that conflict is inherent in their group's developmental process. Source: iStockphoto.com/Yuri_Arcurs. 3. How does the group balance its task and socioemotional needs? According to small group communication researcher Joann Keyton (1997), each time a group member communicates, he or she contributes to the task or social reality of the group, not to both (p. 240). This means a group must pay attention to how its members communicate so that their interaction includes both task-orientation and socioemotional orientation. In Chapter 8, we will discuss how members should engage in role flexibility. By being flexible in how you act and what you say, you can fulfill any role your group needs at any particular time. 4. How does the group communicate? Susan Wheelan and her associates (2003) reported that, with every year of existence, group members engage in less pseudo-work talk (i.e., comments or stories about topics not related to the group task) or disagreements about group procedures and goals. Moreover, they found the members of developed groups consider themselves more effective and productive in how they communicate about the task. 5. How involved is the group with its task? Group member involvement with any task is crucial. As groups begin to move through the developmental process, members make a decision about the group's ability to perform (Baker, 2001). This early decision about group performance affects not only how a group accomplishes a task but also whether group members believe they can accomplish a task. This belief in the group's ability-sometimes referred to as group efficacyis important for members to possess. With group efficacy present, members work together more willingly as a group, report greater learning, and require less supervision to complete their tasks (Pescosolido, 2003). ? How do the members of your work group balance its task and socioemotional needs? How difficult is it to meet both needs? So how do these five characteristics reflect group development? The answer is simple. Fully developed groups include members who are cohesive and able to depersonalize conflict, strike a balance between the group's task and socioemotional needs, engage in effective communication, and possess group efficacy. Yet, of the five characteristics, none is more important than the other. As you look ahead, consider how these five characteristics reflect the developmental process of the groups to which you currently belong. A Final Note About Small Group Development In this chapter, we presented three distinct models of group development. Communication researcher Kenneth Cissna (1984) commented that "every group is like all groups in some respects, like some-or perhaps even most-groups in some respects, and like no groups in other respects (p. 25). Rather than focusing on which model of group development is the most superior, consider that each model explains, to some degree, the ways the groups to which you belong develop. Conclusion This chapter aimed to highlight important concepts researchers have found appropriate when analyzing communication and group development. We discussed how a group's history and maturity level factor into thinking about how prior group experiences and specific task situations influence how members work together. We also examined three models of group development and identified five characteristics of a developed group. As you read the next chapter, consider how a group "A Final Note About Small Group Development the stage, phase, or track at which the group is located within its developmental process. ml.bonito toclcn mor, donnadStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts