Based on the evolution of international marketing since Levitt's article "The Globalization of Markets" published in 1982 and on what you have learned in this course, what do you think the next 20 years of international marketing will look like?

Here are some questions to help you structure your answer:

a) Which countries are likely to be hot spots? (a keyword might be: "Third Wave", then if we are talking about a "third wave," what are the first and second waves?)

b) Do you expect a divergence or convergence in consumer preferences? (With that in mind, how about the relevance of CAGE framework? Will it still be a useful tool?)

c) Based on your thoughts on divergence and convergence, do you think the companies will move towards more adaptation or standardization?

d) How can a non-global company survive global competition?

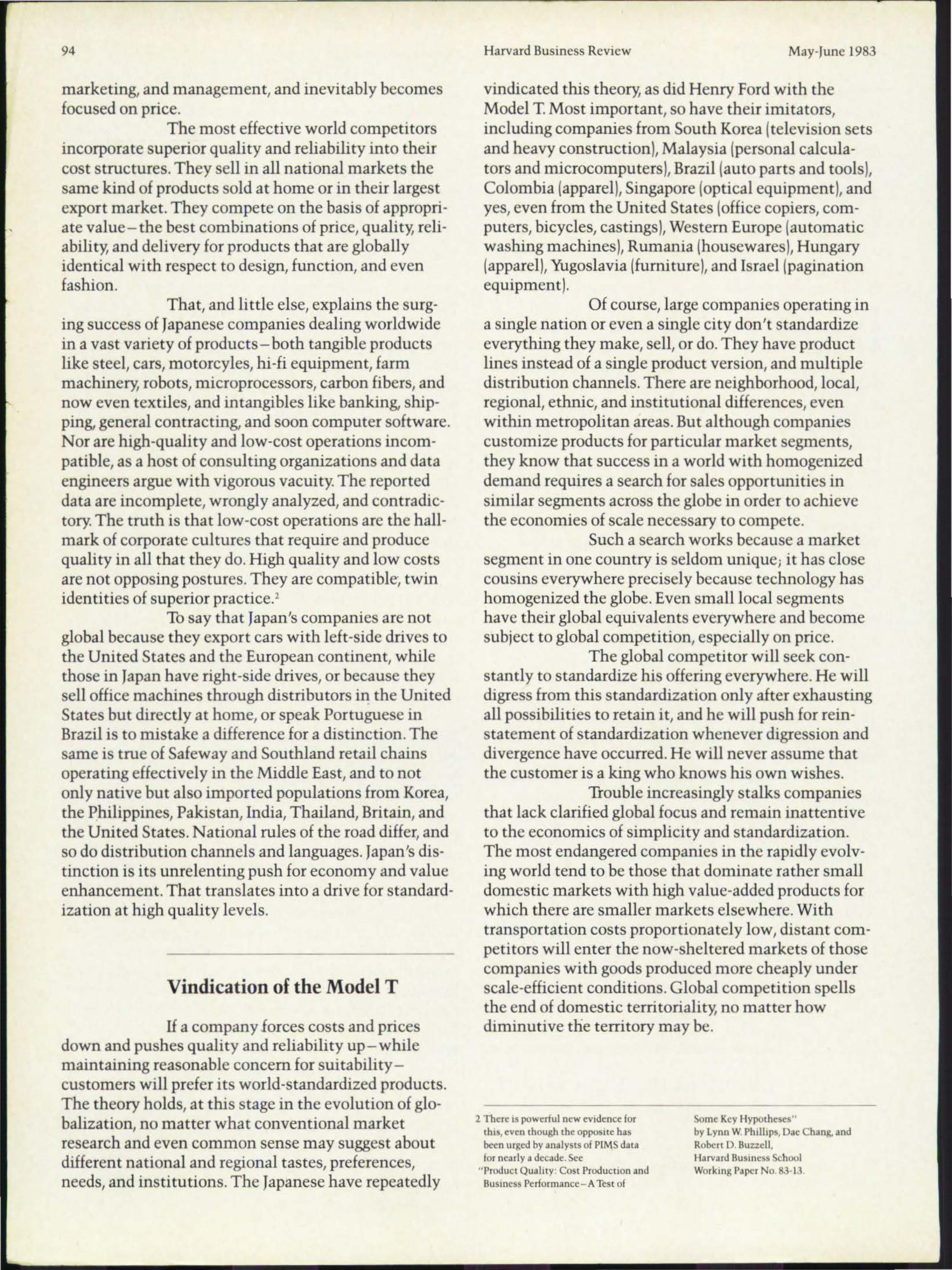

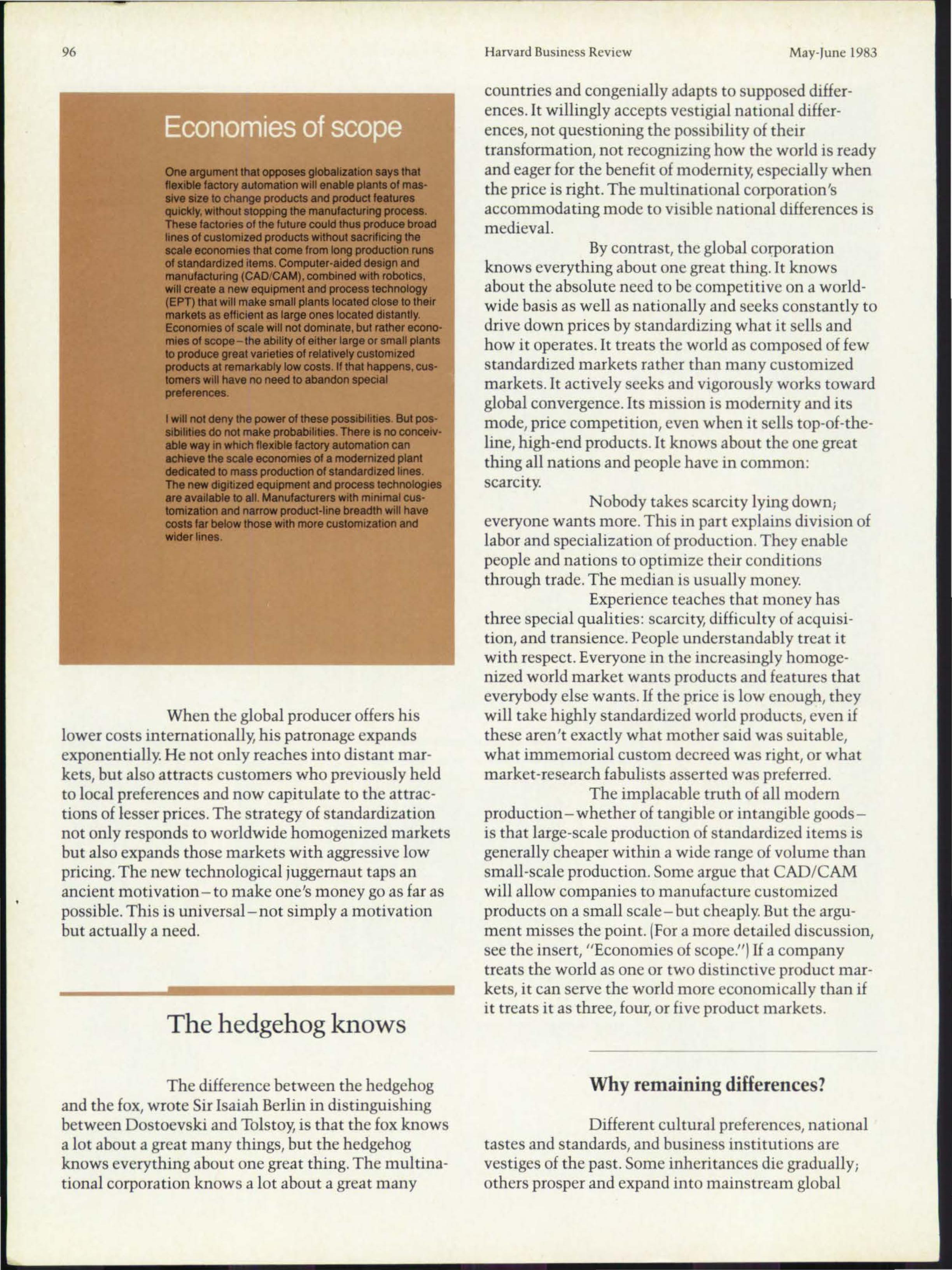

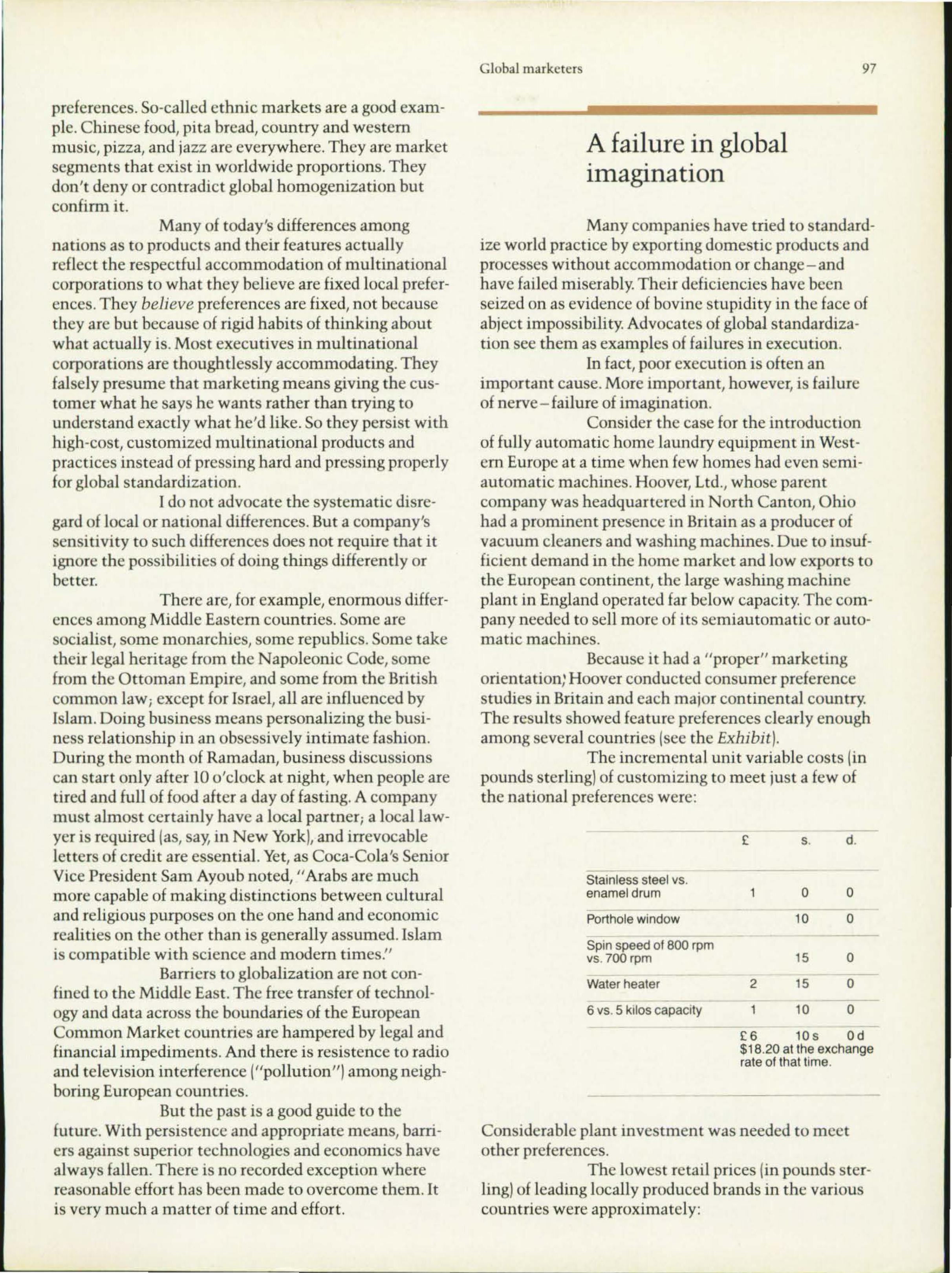

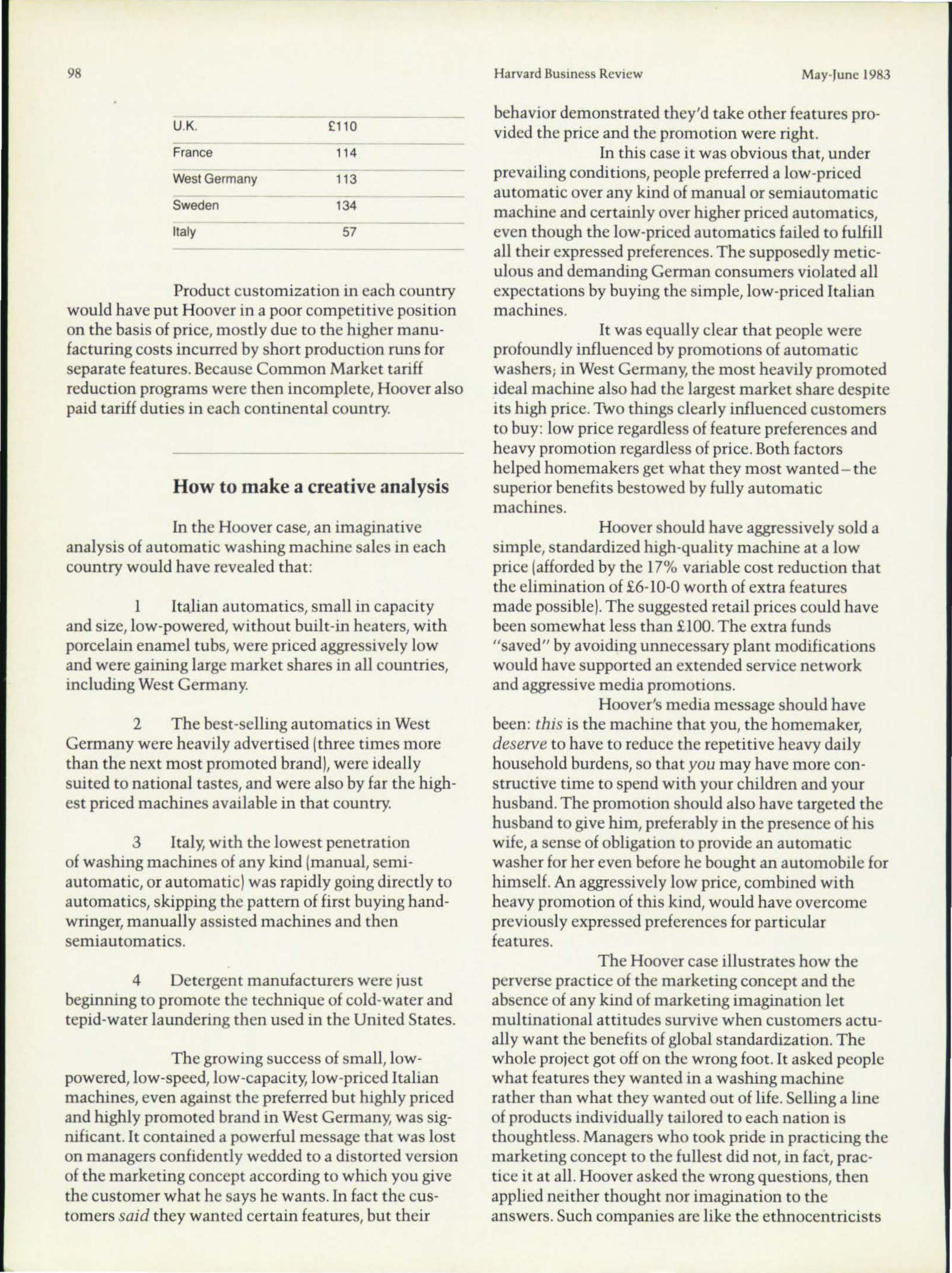

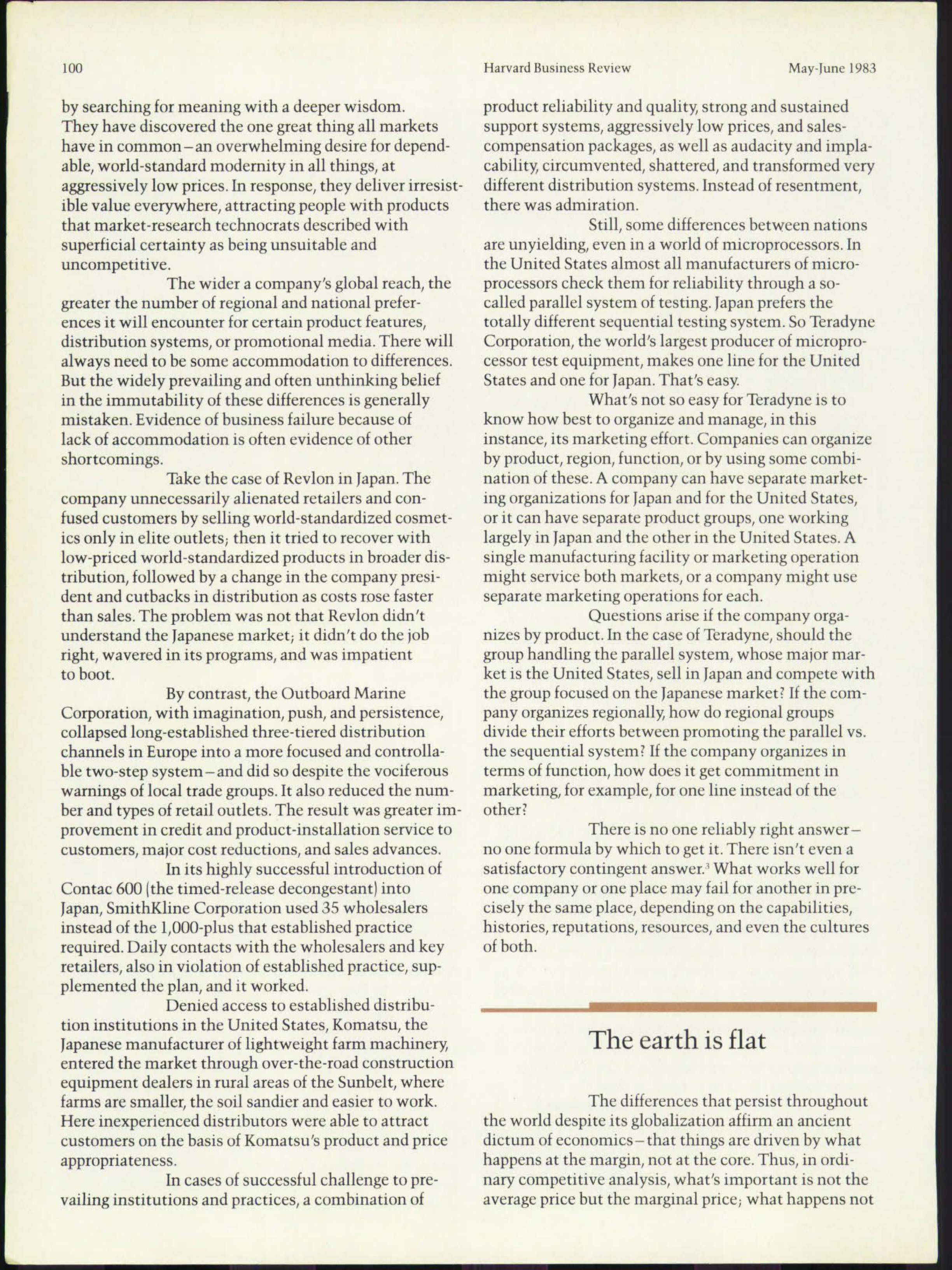

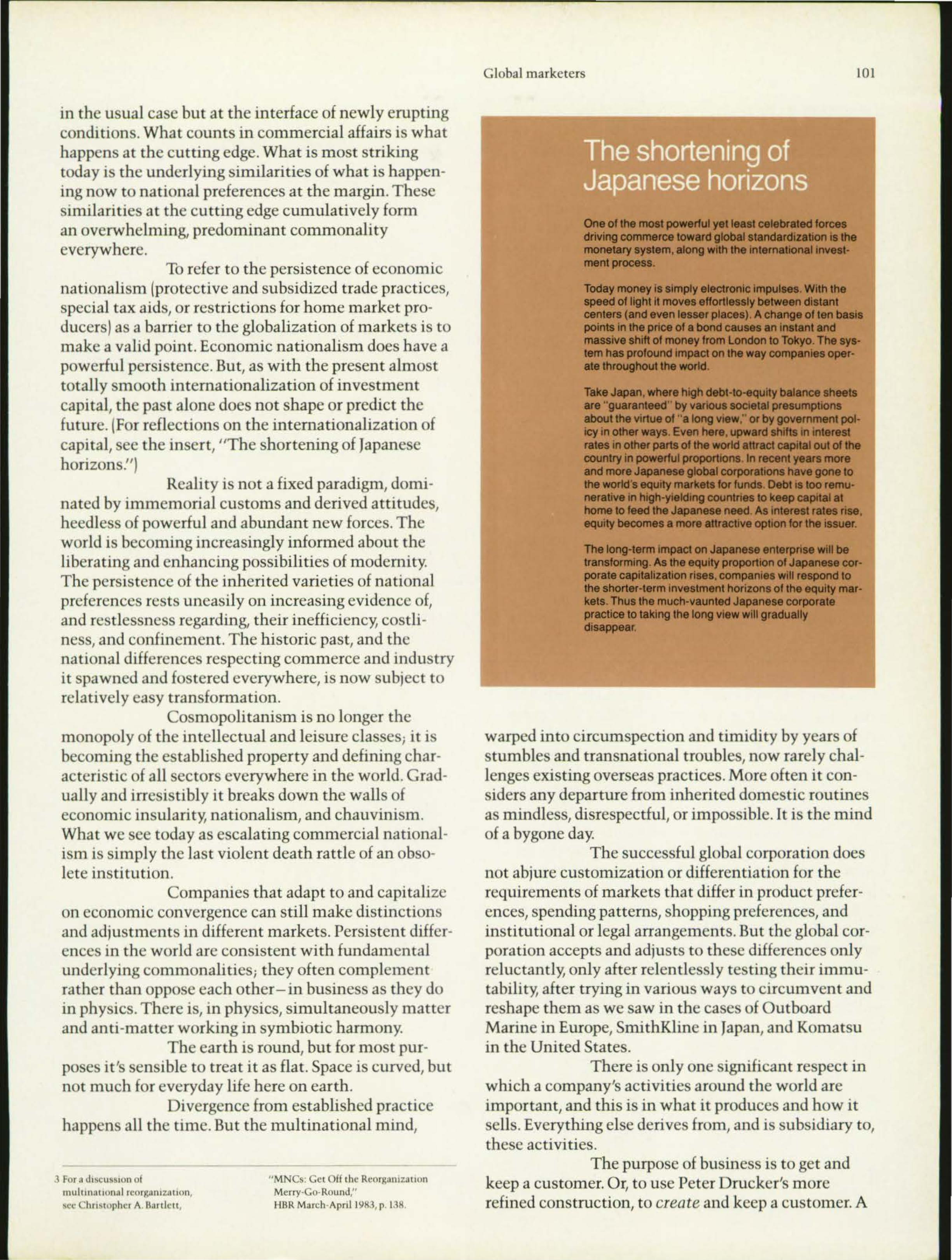

The globalization of markets Theodore Levitt Many companies have become disillu- sioned with sales in the international mar- ketplace as old markets become saturated and new ones must be found. How can they customize products for the demands of new markets! Which items will con- sumers want! With wily international com- peti tors breathing down their necks; many organizations think that the game just isn't worth the effort. In this powerful essay, the author asserts that well-managed companies have moved from emphasis on customizing items to offering globally standardized products that are advanced, functional, reliable- and low priced. Multinational companies that concentrated on idiosyncratic con- sumer preferences have become befuddled and unable to take in the forest because of the trees. Only global companies will achieve long-term success by concentrat- ing on what everyone wants rather than worrying about the details of what every- one thinks they might like. Mr. Levitt is Edward W. Carter Professor of Business Administration and head of the marketing area at the Harvard Business School. This is Mr. Levitt's twen tythird article for HBR; his classic "Marketing M yopia," first published in 1960, was reprinted in September-October 1975, and his last article was \"Marketing Intangible Products and Product Intangibles" (May-lune 1981). Illustration by Karen Watson. Companies must learn to operate as if the world were one large market ignoring superficial regional and national differences A powerful force drives the world toward a converging commonality, and that force is technology. It has proletarianized communication, transport, and travel. It has made isolated places and impoverished peoples eager for modemity's allure- ments. Almost everyone everywhere wants all the things they have heard about, seen, or experienced via the new technologies. The result is a new commercial reality the emergence of global markets for standardized con~ sumer products on a previously unimagined scale of magnitude. Corporations geared to this new reality benefit from enormous economies of scale in produc- tion, distribution, marketing, and management. By translating these benefits into reduced world prices, they can decimate competitors that still live in the disabling grip of old assumptions about how the world works. Gone are accustomed differences in national or regional preference. Gone are the days when a company could sell last year's modelsor lesser versions of advanced products- in the less- developed world. And gone are the days when prices, margins, and profits abroad were generally higher than at home. The globalization of markets is at hand. With that, the multinational commercial world nears its end, and so does the multinational corporation. The multinational and the global corpo- ration are not the same thing. The multinational cor- poration operates in a number of countries, and adjusts its products and practices in each at high relative costs. The global corporation operates with resolute constancy at low relative cost as if the entire world 1 In a landmark article, Robert D. Buncll pointed out the rapidity With which barriers to standardization were falling. In All cases they succumbed lo more and cheaper advanced ways of doing things. Sec \"Can You Standardize Multinational Marketing?" HBR November-December 1968.1). 107.. (or major regions of it) were a single entity; it sells the same things in the same way everywhere. Which strategy is better is not a mat- ter of opinion but of necessity. Worldwide communi- cations carry everywhere the constant drumbeat of modern possibilities to lighten and enhance work, raise living standards, divert, and entertain. The same countries that ask the world to recognize and respect the individuality of their cultures insist on the whole- sale transfer to them of modern goods, services, and technologies. Modernity is not just a wish but also a widespread practice among those who cling, with unyielding passion or religious fervor, to ancient atti- tudes and heritages. Who can forget the televised scenes dur- ing the 1979 Iranian uprisings of young men in fashion- able French-cut trousers and silky body shirts thirsting with raised modern weapons for blood in the name of Islamic fundamentalism? In Brazil, thousands swarm daily from pre-industrial Bahian darkness into exploding coastal cities, there quickly to install television sets in crowded corrugated huts and, next to battered Volkswagens, make sacrificial offerings of fruit and fresh-killed chickens to Macumban spirits by candlelight. During Biafra's fratricidal war against the Ibos, daily televised reports showed soldiers carry- ing bloodstained swords and listening to transistor radios while drinking Coca-Cola. In the isolated Siberian city of Krasno- yarsk, with no paved streets and censored news, occa~ sional Western travelers are stealthy propositioned for cigarettes, digital watches, and even the clothes off their backs. The organized smuggling of electronic equipment, used automobiles, western clothing, cos metics, and pirated movies into primitive places exceeds even the thriving underground trade in mod- em weapons and their military mercenaries. A thousand suggestive ways attest to the ubiquity of the desire for the most advanced things that the world makes and sells-goods of the best qual- ity and reliability at the lowest price. The world's needs and desires have been irrevocably homogenized. This makes the multinational corporation obsolete and the global corporation absolute. Living in the Republic of Technology Daniel I. Boorstin, author of the monu- mental trilogy The Americans, characterized our age Global marketers 93 as driven by \"the Republic of Technology [whose] supreme law...is convergence, the tendency for every- thing to become more like everything else." In business, this trend has pushed mar- kets toward global commonality. Corporations sell standardized products in the same way everywhere autos, steel, chemicals, petroleum, cement, agricul- tural commodities and equipment, industrial and commercial construction, banking and insurance services, computers, semiconductors, transport, electronic instruments, pharmaceuticals, and telecommunications, to mention some of the obvious. Nor is the sweeping gale of globaliza- tion confined to these raw material or high-tech prod- ucts, where the universal language of customers and users facilitates standardization. The transforming winds whipped up by the proletarianization of com- munication and travel enter every crevice of life. Commercially, nothing confirms this as much as the success of McDonald's from the Champs Elyses to the Ginza, of Coca-Cola in Bahrain and Pepsi-Cola in Moscow, and of rock music, Greek salad, Hollywood movies, Revlon cosmetics, Sony televi- sions, and Levi jeans everywhere. \"High-touch" products are as ubiquitous as high-tech. Starting from opposing sides, the high- tech and the high-touch ends of the commercial spec- trum gradually consume the undistributed middle in their cosmopolitan orbit. N 0 one is exempt and noth- ing can stop the process. Everywhere everything gets more and more like everything else as the world's pref- erence structure is relentlessly homogenized. Consider the cases of Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola, which are globally standardized products sold everywhere and welcomed by everyone. Both successfully cross multitudes of national, regional, and ethnic taste buds trained to a variety of deeply ingrained local preferences of taste, flavor, consistency, effervescence, and aftertaste. Everywhere both sell well. Cigarettes, too, especially American-made, make year-to-year global inroads on territories previously held in the firm grip of other, mostly local, blends. These are not exceptional examples. (Indeed their global reach would be even greater were it not for artificial trade barriers.) They exemplify a gen- eral drift toward the homogenization of the world and how companies distribute, finance, and price products.' Nothing is exempt. The products and methods of the industrialized world play a single tune for all the world, and all the world eagerly dances to it. Ancient differences in national tastes or modes of doing business disappear. The commonality of preference leads inescapably to the standardization of products, manufacturing, and the institutions of trade and commerce. Small nation-based markets transmogrify and expand. Success in world competi- tion turns on efficiency in production, distribution, 94 marketing, and management, and inevitably becomes focused on price. The most effective world competitors incorporate superior quality and reliability into their cost structures. They sell in all national markets the same kind of products sold at home or in their largest export market. They compete on the basis of appropri- ate valuethe best combinations of price, quality, reli- ability, and delivery for products that are globally identical with respect to design, function, and even fashion. That, and little else, explains the surg- ing success of Japanese companies dealing worldwide in a vast variety of productsboth tangible products like steel, cars, motorcyles, hi-fi equipment, farm machinery, robots, microprocessors, carbon fibers, and now even textiles, and intangibles like banking, ship- ping, general contracting, and soon computer software. Nor are high-quality and low-cost operations incom- patible, as a host of consulting organizations and data engineers argue with vigorous vacuity. The reported data are incomplete, wrongly analyzed, and contradic- tory. The truth is that low-cost operations are the hall- mark of corporate cultures that require and produce quality in all that they do. High quality and low costs are not opposing postures. They are compatible, twin identities of superior practice} 'Ib say that Japan's companies are not global because they export cars with left-side drives to the United States and the European continent, while those in Iapan have right-side drives, or because they sell office machines through distributors in the United States but directly at home, or speak Portuguese in Brazil is to mistake a difference for a distinction. The same is true of Safeway and Southland retail chains operating effectively in the Middle East, and to not only native but also imported populations from Korea, the Philippines, Pakistan, India, Thailand, Britain, and the United States. National rules of the road differ, and so do distribution channels and languages. Japan's dis- tinction is its unrelenting push for economy and value enhancement. That translates into a drive for standard ization at high quality levels. Vindication of the Model T If a company forces costs and prices down and pushes quality and reliability up- while maintaining reasonable concern for suitability customers will prefer its world-standardized products. The theory holds, at this stage in the evolution of glo- balization, no matter what conventional market research and even common sense may suggest about different national and regional tastes, preferences, needs, and institutions. The Japanese have repeatedly Harvard Business Review May-lune 1983 vindicated this theory, as did Henry Ford with the Model T. Most important, so have their imitators, including companies from South Korea (television sets and heavy construction), Malaysia (personal calcula- tors and microcomputers), Brazil (auto parts and tools), Colombia (apparel), Singapore (optical equipment), and yes, even from the United States (office copiers, com- puters, bicycles, castings), Western Europe (automatic washing machines), Rumania (housewares), Hungary (apparel), Yugoslavia (furniture), and Israel (pagination equipment). Of course, large companies operating in a single nation or even a single city don't standardize everything they make, sell, or do. They have product lines instead of a single product version, and multiple distribution channels. There are neighborhood, local, regional, ethnic, and institutional differences, even within metropolitan areas. But although companies customize products for particular market segments, they know that success in a world with homogenized demand requires a search for sales opportunities in similar segments across the globe in order to achieve the economies of scale necessary to compete. Such a search works because a market segment in one country is seldom unique; it has close cousins everywhere precisely because technology has homogenized the globe. Even small local segments have their global equivalents everywhere and become subject to global competition, especially on price. The global competitor will seek con- stantly to standardize his offering everywhere. He will digress from this standardization only after exhausting all possibilities to retain it, and he will push for rein- statement of standardization whenever digression and divergence have occurred. He will never assume that the customer is a king who knows his own wishes. 'Ii'ouble increasingly stalks companies that lack clarified global focus and remain inattentive to the economics of simplicity and standardization. The most endangered companies in the rapidly evolv' ing world tend to be those that dominate rather small domestic markets with high value-added products for which there are smaller markets elsewhere. With transportation costs proportionately low, distant com- petitors will enter the now-sheltered markets of those companies with goods produced more cheaply under scale~efficient conditions. Global competition spells the end of domestic territoriality, no matter how diminutive the territory may be. Some Key Hypotheses" by Lynn W. Phillips, Dat- Chang. and Robert D. Buzzell, Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 83-13. 2 There is powerful new evidence for this, even though the opposite has been urged by analysts of HMS data bur nearly a decade. See "Pmduct Quality: Cost Production and Business Performance- A'ltst uf \f96 Harvard Business Review May-June 1983 countries and congenially adapts to supposed differ- ences. It willingly accepts vestigial national differ- Economies of scope ences, not questioning the possibility of their transformation, not recognizing how the world is ready One argument that opposes globalization says that and eager for the benefit of modernity, especially when flexible factory automation will enable plants of mas- sive size to change products and product features the price is right. The multinational corporation's quickly, without stopping the manufacturing process accommodating mode to visible national differences is These factories of the future could thus produce broad lines of customized products witho medieval. scale economies that come from long production runs By contrast, the global corporation of standardized items. Computer-aided design and manufacturing (CAD/CAM), combined with robotics knows everything about one great thing. It knows will create a new equipment and process technology about the absolute need to be competitive on a world- (EPT) that will make small plants located close to their markets as efficient as large ones located distantly. wide basis as well as nationally and seeks constantly to Economies of scale will not dominate, but rather econo- drive down prices by standardizing what it sells and mies of scope -the ability of either large or small plants to produce great varieties of relatively customized how it operates. It treats the world as composed of few products at remarkably low costs. If that happens, cus- standardized markets rather than many customized tomers will have no need to abandon special preferences. markets. It actively seeks and vigorously works toward global convergence. Its mission is modernity and its I will not deny the power of these possibilities. But pos- sibilities do not make probabilities. There is no conceiv mode, price competition, even when it sells top-of-the- able way in which flexible factory automation can line, high-end products. It knows about the one great achieve the scale economies of a modernized plant dedicated to mass production of standardized lines. thing all nations and people have in common: The new digitized equipment and process technologies scarcity. are available to all. Manufacturers with minimal cus- tomization and narrow product-line breadth will have Nobody takes scarcity lying down; costs far below those with more customization and everyone wants more. This in part explains division of wider lines. labor and specialization of production. They enable people and nations to optimize their conditions through trade. The median is usually money. Experience teaches that money has three special qualities: scarcity, difficulty of acquisi- tion, and transience. People understandably treat it with respect. Everyone in the increasingly homoge- nized world market wants products and features that everybody else wants. If the price is low enough, they When the global producer offers his will take highly standardized world products, even if lower costs internationally, his patronage expands these aren't exactly what mother said was suitable, exponentially. He not only reaches into distant mar- what immemorial custom decreed was right, or what kets, but also attracts customers who previously held market-research fabulists asserted was preferred. to local preferences and now capitulate to the attrac- The implacable truth of all modern tions of lesser prices. The strategy of standardization production-whether of tangible or intangible goods- not only responds to worldwide homogenized markets is that large-scale production of standardized items is but also expands those markets with aggressive low generally cheaper within a wide range of volume than pricing. The new technological juggernaut taps an small-scale production. Some argue that CAD/CAM ancient motivation-to make one's money go as far as will allow companies to manufacture customized possible. This is universal-not simply a motivation products on a small scale-but cheaply. But the argu- but actually a need. ment misses the point. (For a more detailed discussion, see the insert, "Economies of scope.") If a company treats the world as one or two distinctive product mar- kets, it can serve the world more economically than if The hedgehog knows it treats it as three, four, or five product markets. The difference between the hedgehog Why remaining differences? and the fox, wrote Sir Isaiah Berlin in distinguishing between Dostoevski and Tolstoy, is that the fox knows Different cultural preferences, national a lot about a great many things, but the hedgehog tastes and standards, and business institutions are knows everything about one great thing. The multina- vestiges of the past. Some inheritances die gradually; tional corporation knows a lot about a great many others prosper and expand into mainstream globalpreferences. So-called ethnic markets are a good exam- ple. Chinese food, pita bread, country and western music, pizza, and jazz are everywhere. They are market segments that exist in worldwide proportions. They don't deny or contradict global homogenization but confirm it. Many of today's differences among nations as to products and their features actually reect the respectful accommodation of multinational corporations to what they believe are xed local prefer- ences. They believe preferences are fixed, not because they are but because of rigid habits of thinking about what actually is. Most executives in multinational corporations are thoughtlessly accommodating. They falsely presume that marketing means giving the cus- tomer what he says he wants rather than trying to understand exactly what he'd like. So they persist with high-cost, customized multinational products and practices instead of pressing hard and pressing properly for global standardization. I do not advocate the systematic disre- gard of local or national differences. But a company's sensitivity to such differences does not require that it ignore the possibilities of doing things differently or better. There are, for example, enormous differ- ences among Middle Eastern countries. Some are socialist, some monarchies, some republics. Some take their legal heritage from the Napoleonic Code, some from the Ottoman Empire, and some from the British common law; except for Israel, all are inuenced by Islam. Doing business means personalizing the busi- ness relationship in an obsessively intimate fashion. During the month of Ramadan, business discussions can start only after 10 o'clock at night, when people are tired and full of food after a day of fasting. A company must almost certainly have a local partner; a local law- yer is required (as, say, in New York), and irrevocable letters of credit are essential. Yet, as Coca-Cola's Senior Vice President Sam Ayoub noted, \"Arabs are much more capable of making distinctions between cultural and religious purposes on the one hand and economic realities on the other than is generally assumed. Islam is compatible with science and modern times.\" Barriers to globalization are not con- fined to the Middle East. The free transfer of technol- ogy and data across the boundaries of the European Common Market countries are hampered by legal and financial impediments. And there is resistence to radio and television interference (\"pollution\") among neigh- boring European countries. But the past is a good guide to the future. With persistence and appropriate means, barri- ers against superior technologies and economics have always fallen. There is no recorded exception where reasonable effort has been made to overcome them. It is very much a matter of time and effort. Global marketers 97 A failure in global imagination Many companies have tried to standard- ize world practice by exporting domestic products and processes without accommodation or change and have failed miserany Their deciencies have been seized on as evidence of bovine stupidity in the face of abject impossibility. Advocates of global standardiza- tion see them as examples of failures in execution. In fact, poor execution is often an important cause. More important, however, is failure of nerve- failure of imagination. Consider the case for the introduction of fully automatic home laundry equipment in West- ern Europe at a time when few homes had even semi- automatic machines. Hoover, Ltd., whose parent company was headquartered in North Canton, Ohio had a prominent presence in Britain as a producer of vacuum cleaners and washing machines. Due to insuf- ficient demand in the home market and low exports to the European continent, the large washing machine plant in England operated far below capacity. The com- pany needed to sell more of its semiautomatic or auto- matic machines. Because it had a "proper\" marketing orientation; Hoover conducted consumer preference studies in Britain and each major continental country. The results showed feature preferences clearly enough among several countries )see the Exhibit). The incremental unit variable costs {in pounds sterling) of customizing to meet just a few of the national preferences were: 5. d. StainleSs steel vs. - 7 if enamel drum 1 0 0 Porthole window ' _, ' 1o 6 -. ' SpinspeedofBOOrpm \"i 7 v vs. 700 rpm 15 0 Water heater _ _ V27 15\" 7 70 6vs.5kiiocpaym 71 10' o 77"\" s:6 '7 170's id $18.20 at the exchange rate 01 that time. Considerable plant investment was needed to meet other preferences. The lowest retail prices [in pounds ster- ling) of leading locally produced brands in the various countries were approximately: 98 UK. 7 7 130 e; m _ West Germany 113 A Sweden 134 italy 5:! Product customization in each country would have put Hoover in a poor competitive position on the basis of price, mostly due to the higher manu- facturing costs incurred by short production runs for separate features. Because Common Market tariff reduction programs were then incomplete, Hoover also paid tariff duties in each continental country. How to make a creative analysis In the Hoover case, an imaginative analysis of automatic washing machine sales in each country would have revealed that: 1 Italian automatics, small in capacity and size, low-powered, without built-in heaters, with porcelain enamel tubs, were priced aggressively low and were gaining large market shares in all countries, including West Germany. 2 The best-selling automatics in West Germany were heavily advertised (three times more than the next most promoted brand), were ideally suited to national tastes, and were also by far the high- est priced machines available in that country. 3 Italy, with the lowest penetration of washing machines of any kind (manual, semi automatic, or automatic) was rapidly going directly to automatics, skipping the pattern of first buying hand- wringer, manually assisted machines and then semiautomatics. 4 Detergent manufacturers were just beginning to promote the technique of cold-water and tepid-water laundering then used in the United States. The growing success of small, low- powered, low-speed, low-capacity, low-priced Italian machines, even against the preferred but highly priced and highly promoted brand in West Germany, was sig- nificant. It contained a powerful message that was lost on managers confidently wedded to a distorted version of the marketing concept according to which you give the customer what he says he wants. In fact the cus- tomers said they wanted certain features, but their Harvard Business Review May-lune I983 behavior demonstrated they'd take other features pro- vided the price and the promotion were right. In this case it was obvious that, under prevailing conditions, people preferred a low-priced automatic over any kind of manual or semiautomatic machine and certainly over higher priced automatics, even though the low-priced automatics failed to fulfill all their expressed preferences. The supposedly metic- ulous and demanding German consumers violated all expectations by buying the simple, low-priced Italian machines. It was equally clear that people were profoundly inuenced by promotions of automatic washers; in West Germany, the most heavily promoted ideal machine also had the largest market share despite its high price. TWO things clearly inuenced customers to buy: low price regardless of feature preferences and heavy promotion regardless of price. Both factors helped homemakers get what they most wanted- the superior benefits bestowed by fully automatic machines. Hoover should have aggressively sold a simple, standardized high-quality machine at a low price (afforded by the 17% variable cost reduction that the elimination of 5.6-10-0 worth of extra features made possible). The suggested retail prices could have been somewhat less than 100. The extra funds "saved" by avoiding unnecessary plant modifications would have supported an extended service network and aggressive media promotions. Hoover's media message should have been: this is the machine that you, the homemaker, deserve to have to reduce the repetitive heavy daily household burdens, so that you may have more con- structive time to spend with your children and your husband. The promotion should also have targeted the husband to give him, preferably in the presence of his wife, a sense of obligation to provide an automatic washer for her even before he bought an automobile for himself. An aggressively low price, combined with heavy promotion of this kind, would have overcome previously expressed preferences for particular features. The Hoover case illustrates how the perverse practice of the marketing concept and the absence of any kind of marketing imagination let multinational attitudes survive when customers actu- ally want the benefits of global standardization. The whole project got off on the wrong foot. It asked people what features they wanted in a washing machine rather than what they wanted out of life. Selling a line of products individually tailored to each nation is thoughtless. Managers who took pride in practicing the marketing concept to the fullest did not, in fact, prac- tice it at all. Hoover asked the wrong questions, then applied neither thought nor imagination to the answers. Such companies are like the ethnocentricists Global marketers 99 Exhibit Consumer preferences as to automatic washing machine features in the 1960s Features Great Britain Italy West Germany France Sweden Shell dimensions" 34" Low 34" 34" 34" and narrow and narrow and wide and narrow and wide Drum material Enamel Enamel Stainless Enamel Stainless steel steel Loading Top Front Front Front Front Front porthole Yeso Yes Yes Yes Yes Capacity 5 kilos 4 kilos 6 kilos 5 kilos 6 kilos Spin speed 700 rpm 400 rpm 850 rpm 600 rpm 800 rpm Water-heating Not Yes Yest Yes No system Washing action Agitator Tumble Tumble Agitator Tumble Styling features Inconspicuous Brightly Indestructible Elegant Strong appearance colored appearance appearance appearance *34" height was (in the process of being Most British and Swedish homes had adopted as) a standard work-surface centrally heated hot water. height in Europe. itWest Germans preferred temperatures higher than generally provided centrally. in the Middle Ages who saw with everyday clarity the not shut down General Motors since 1970. Both unions sun revolving around the earth and offered it as Truth. realize that they have become global -shutting down With no additional data but a more searching mind, all or most of U.S. manufacturing would not shut out Copernicus, like the hedgehog, interpreted a more U.S. customers. Overseas suppliers are there to supply compelling and accurate reality. Data do not yield the market. information except with the intervention of the mind. Information does not yield meaning except with the intervention of imagination. Cracking the code of Western markets Accepting the inevitable Since the theory of the marketing concept emerged a quarter of a century ago, the more managerially advanced corporations have been eager to offer what customers clearly wanted rather than what The global corporation accepts for bet- was merely convenient. They have created marketing ter or for worse that technology drives consumers departments supported by professional market relentlessly toward the same common goals- researchers of awesome and often costly proportions. alleviation of life's burdens and the expansion of dis- And they have proliferated extraordinary numbers of cretionary time and spending power. Its role is operations and product lines-highly tailored products profoundly different from what it has been for the ordi- and delivery systems for many different markets, mar- nary corporation during its brief, turbulent, and ket segments, and nations. remarkably protean history. It orchestrates the twin Significantly, Japanese companies oper- vectors of technology and globalization for the world's ate almost entirely without marketing departments or benefit. Neither fate, nor nature, nor God but rather market research of the kind so prevalent in the West. the necessity of commerce created this role. Yet, in the colorful words of General Electric's chair- In the United States two industries man John F. Welch, Jr., the Japanese, coming from a became global long before they were consciously small cluster of resource-poor islands, with an entirely aware of it. After over a generation of persistent and alien culture and an almost impenetrably complex lan- acrimonious labor shutdowns, the United Steel- guage, have cracked the code of Western markets. They workers of America have not called an industrywide have done it not by looking with mechanistic thor- strike since 1959; the United Auto Workers have oughness at the way markets are different but rather100 by searching for meaning with a deeper wisdom. They have discovered the one great thing all markets have in commonan overwhelming desire for depend- able, world-standard modernity in all things, at aggressively low prices. In response, they deliver irresist- ible value everywhere, attracting people with products that market-research technocrats described with superficial certainty as being unsuitable and uncompetitive. The wider a company's global reach, the greater the number of regional and national prefer- ences it will encounter for certain product features, distribution systems, or promotional media. There will always need to be some accommodation to differences. But the widely prevailing and often unthinking belief in the immutability of these differences is generally mistaken. Evidence of business failure because of lack of accommodation is often evidence of other shortcomings. Take the case of Revlon in Japan. The company unnecessarily alienated retailers and con- fused customers by selling world-standardized cosmet- ics only in elite outlets ,- then it tried to recover with low-priced world-standardized products in broader dis- tribution, followed by a change in the company presi- dent and cutbacks in distribution as costs rose faster than sales. The problem was not that Revlon didn't understand the Japanese market,- it didn't do the job right, wavered in its programs, and was impatient to boot. By contrast, the Outboard Marine Corporation, with imagination, push, and persistence, collapsed long-established three-tiered distribution channels in Europe into a more focused and controlla- ble two-step system-and did so despite the vociferous warnings of local trade groups. It also reduced the num- ber and types of retail outlets. The result was greater im- provement in credit and product-installation service to customers, major cost reductions, and sales advances. In its highly successful introduction of Contac 600 [the timed-release decongestant) into Japan, SmithKline Corporation used 35 wholesalers instead of the LOGOplus that established practice required. Daily contacts with the wholesalers and key retailers, also in violation of established practice, sup- plemented the plan, and it worked. Denied access to established distribu- tion institutions in the United States, Komatsu, the Japanese manufacturer of lightweight farm machinery, entered the market through over-the-road construction equipment dealers in rural areas of the Sunbelt, where farms are smaller, the soil sandier and easier to work. Here inexperienced distributors were able to attract customers on the basis of Komatsu's product and price appropriateness. In cases of successful challenge to pre- vailing institutions and practices, a combination of Harvard Business Review May-June 1983 product reliability and quality, strong and sustained support systems, aggressively low prices, and sales- compensation packages, as well as audacity and impla- cability, circumvented, shattered, and transformed very different distribution systems. Instead of resentment, there was admiration. Still, some differences between nations are unyielding, even in a world of microprocessors. In the United States almost all manufacturers of micro- processors check them for reliability through a so- called parallel system of testing. Japan prefers the totally different sequential testing system. So Teradyne Corporation, the world's largest producer of micropro cessor test equipment, makes one line for the United States and one for Japan. That's easy. What's not so easy for Teradyne is to know how best to organize and manage, in this instance, its marketing effort. Companies can organize by product, region, function, or by using some combi- nation of these. A company can have separate marketv ing organizations for Japan and for the United States, or it can have separate product groups, one working largely in Japan and the other in the United States. A single manufacturing facility or marketing operation might service both markets, or a company might use separate marketing operations for each. Questions arise if the company orga- nizes by product. In the case of Teradyne, should the group handling the parallel system, whose major mar- ket is the United States, sell in Japan and compete with the group focused on the Japanese market? If the com- pany organizes regionally, how do regional groups divide their efforts between promoting the parallel vs. the sequential system? If the company organizes in terms of function, how does it get commitment in marketing, for example, for one line instead of the other? There is no one reliably right answer no one formula by which to get it. There isn't even a satisfactory contingent answer.3 What works well for one company or one place may fail for another in pre- cisely the same place, depending on the capabilities, histories, reputations, resources, and even the cultures of both. The earth is flat The differences that persist throughout the world despite its globalization afrm an ancient dictum of economicsthat things are driven by what happens at the margin, not at the core. Thus, in ordi- nary competitive analysis, what's important is not the average price but the marginal price ; what happens not Global marketers 101 in the usual case but at the interface of newly erupting conditions. What counts in commercial affairs is what happens at the cutting edge. What is most striking The shortening of today is the underlying similarities of what is happen- ing now to national preferences at the margin. These Japanese horizons similarities at the cutting edge cumulatively form an overwhelming, predominant commonality One of the most powerful yet least celebrated forces driving commerce toward global standardization is the everywhere. monetary system, along with the international invest- To refer to the persistence of economic ment process. nationalism (protective and subsidized trade practices, Today money is simply electronic impulses. With the special tax aids, or restrictions for home market pro- speed of light it moves effortlessly between distant centers (and even lesser places). A change of ten basis ducers) as a barrier to the globalization of markets is to points in the price of a bond causes an instant and make a valid point. Economic nationalism does have a massive shift of money from London to Tokyo. The sys- tem has profound impact on the way companies oper- powerful persistence. But, as with the present almost ate throughout the world. totally smooth internationalization of investment Take Japan, where high debt-to-equity balance sheets capital, the past alone does not shape or predict the are "guaranteed" by various societal presumptions future. (For reflections on the internationalization of about the virtue of "a long view," or by government pol- icy in other ways. Even here, upward shifts in interest capital, see the insert, "The shortening of Japanese rates in other parts of the world attract capital out of the horizons.") country in powerful proportions, In recent years more and more Japanese global corporations have gone to Reality is not a fixed paradigm, domi- the world's equity markets for funds. Debt is too remu- nated by immemorial customs and derived attitudes, nerative in high-yielding countries to keep capital at home to feed the Japanese need. As interest rates rise heedless of powerful and abundant new forces. The equity becomes a more attractive option for the issuer. world is becoming increasingly informed about the The long-term impact on Japanese enterprise will be liberating and enhancing possibilities of modernity. transforming. As the equity proportion of Japanese cor- The persistence of the inherited varieties of national porate capitalization rises, companies will respond to the shorter-term investment horizons of the equity mar- preferences rests uneasily on increasing evidence of, kets. Thus the much-vaunted Japanese corporate and restlessness regarding, their inefficiency, costli- practice to taking the long view will gradually disappear. ness, and confinement. The historic past, and the national differences respecting commerce and industry it spawned and fostered everywhere, is now subject to relatively easy transformation. Cosmopolitanism is no longer the monopoly of the intellectual and leisure classes; it is warped into circumspection and timidity by years of becoming the established property and defining char- stumbles and transnational troubles, now rarely chal- acteristic of all sectors everywhere in the world. Grad- lenges existing overseas practices. More often it con- ually and irresistible it breaks down the walls of siders any departure from inherited domestic routines economic insularity, nationalism, and chauvinism. as mindless, disrespectful, or impossible. It is the mind What we see today as escalating commercial national- of a bygone day. ism is simply the last violent death rattle of an obso- The successful global corporation does lete institution. not abjure customization or differentiation for the Companies that adapt to and capitalize requirements of markets that differ in product prefer- on economic convergence can still make distinctions ences, spending patterns, shopping preferences, and and adjustments in different markets. Persistent differ- institutional or legal arrangements. But the global cor- ences in the world are consistent with fundamental poration accepts and adjusts to these differences only underlying commonalities; they often complement reluctantly, only after relentlessly testing their immu- rather than oppose each other-in business as they do tability, after trying in various ways to circumvent and in physics. There is, in physics, simultaneously matter reshape them as we saw in the cases of Outboard and anti-matter working in symbiotic harmony. Marine in Europe, SmithKline in Japan, and Komatsu The earth is round, but for most pur- in the United States. poses it's sensible to treat it as flat. Space is curved, but There is only one significant respect in not much for everyday life here on earth. which a company's activities around the world are Divergence from established practice important, and this is in what it produces and how it happens all the time. But the multinational mind, sells. Everything else derives from, and is subsidiary to, these activities. The purpose of business is to get and 3For a discussion of "MNCs: Get Off the Reorganization multinational reorganization, Merry-Go-Round," keep a customer. Or, to use Peter Drucker's more see Christopher A. Bartlett, HBR March-April 1983, p. 138. refined construction, to create and keep a customer. A102 Harvard Business Review May-June 1983 company must be wedded to the ideal of innovation- offering better or more preferred products in such com- binations of ways, means, places, and at such prices Turtles all the way that prospects prefer doing business with the company rather than with others. down Preferences are constantly shaped and reshaped. Within our global commonality enormous There is an Indian story - at least I heard it as an Indian story-about an Englishman who, having been told that variety constantly asserts itself and thrives, as can be the world rested on a platform which rested on the back seen within the world's single largest domestic mar- of an elephant which rested in turn on the back of a tur- tle, asked (perhaps he was an ethnographer; it is the ket, the United States. But in the process of world way they behave), what did the turtle rest on? Another homogenization, modern markets expand to reach turtle. And that turtle? "Ah, Sahib, after that it is turtles all the way down."... cost-reducing global proportions. With better and cheaper communication and transport, even small The danger that cultural analysis, in search of all-too- deep-lying turtles, will lose touch with the hard surfaces local market segments hitherto protected from distant of life- with the political, economic, stratificati competitors now feel the pressure of their presence ties within which men are everywhere contained - and with the biological and physical necessities on which Nobody is safe from global reach and the irresistible those surfaces rest, is an ever-present one. The only economies of scale. defense against it, and against, thus, turning cultural analysis into a kind of sociological aestheticism, is to Two vectors shape the world- train such analysis on such realities and such necessi- technology and globalization. The first helps deter- ties in the first place. mine human preferences; the second, economic realities. Regardless of how much preferences evolve From Clifford Geertz, and diverge, they also gradually converge and form The Interpretation of Cultures markets where economies of scale lead to reduction of (New York: Basic Books 1973). With permission of the publisher costs and prices. The modern global corporation con- trasts powerfully with the aging multinational cor- poration. Instead of adapting to superficial and even entrenched differences within and between nations, it will seek sensibly to force suitably standardized prod- ucts and practices on the entire globe. They are exactly what the world will take, if they come also with low prices, high quality, and blessed reliability. The global company will operate, in this regard, precisely as Henry Kissinger wrote in Years of Upheaval about the continuing Japanese economic success-"voracious in its collection of information, impervious to pressure, and implacable in execution." Given what is everywhere the purpose of commerce, the global company will shape the vec- tors of technology and globalization into its great strategic fecundity. It will systematically push these vectors toward their own convergence, offering every- one simultaneously high-quality, more or less stan- dardized products at optimally low prices, thereby achieving for itself vastly expanded markets and prof- its. Companies that do not adapt to the new global realities will become victims of those that do.Copyright 1983 Harvard Business Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Additional restrictions may apply including the use of this content as assigned course material. Please consult your institution's librarian about any restrictions that might apply under the license with your institution. For more information and teaching resources om Harvard Business Publishing including Harvard Business School Cases, eLeaming products, and business simulations please visit hb spharvardedu