Question: Based on the reading of the case, carefully explore the following questions faced by Salsgiver (pg. 1): 1. How many of Arrow's customers were likely

Based on the reading of the case, carefully explore the following questions faced by Salsgiver (pg. 1):

1. How many of Arrow's customers were likely to switch some of their

purchases to Express? (Use figures to calculate) 2. How would this affect Arrow's sales and profitability? (Use figures to

calculate) 3. How would Arrow's suppliers react to Express?

Doing the calculations, keep these points in mind:

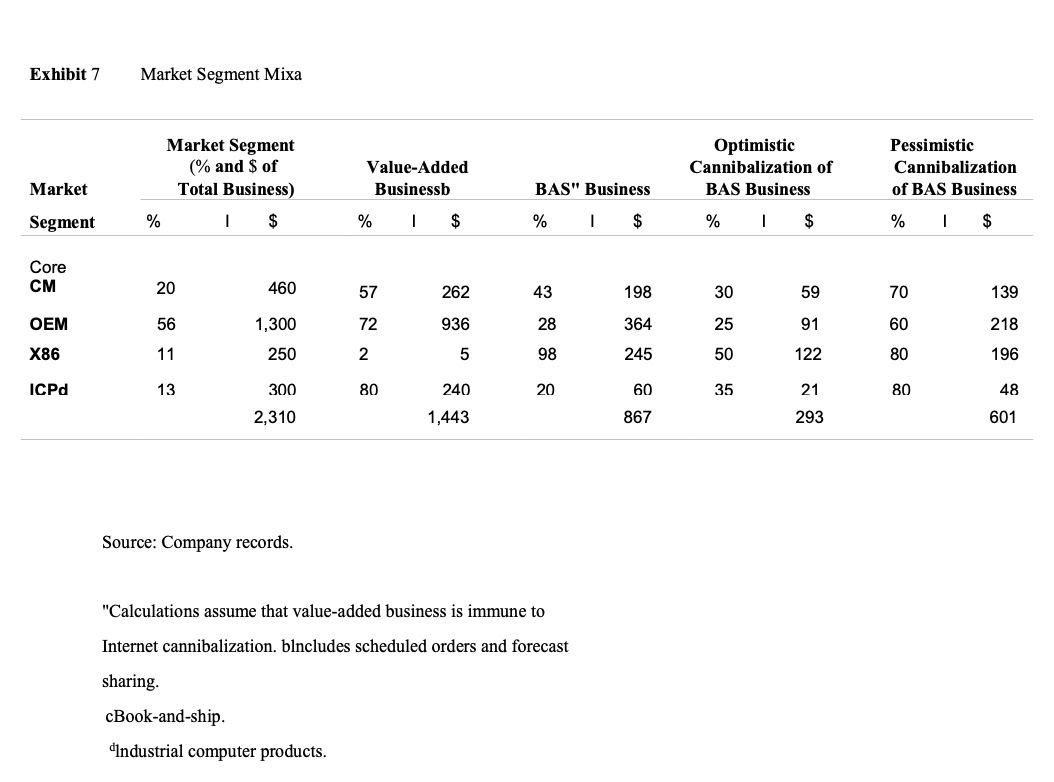

Page 11: All transactional will move to express in an optimistic scenario. And under pessimistic scenario all transactional and 40% of all relational will switch. This is a bit confusing. Look at exhibit 4. 60 percent of their sales have a value-added content. These 60% will not switch as value added content cannot be "shipped" out to express. The remaining 40% will switch. Yes?

Note also that gross margins of 12.5 and 22.5 are for VA and BAS products. We are not given the margins for transactional and relational customers. Yes? Read page 11, under "decision" carefully. (Also see exh 4)

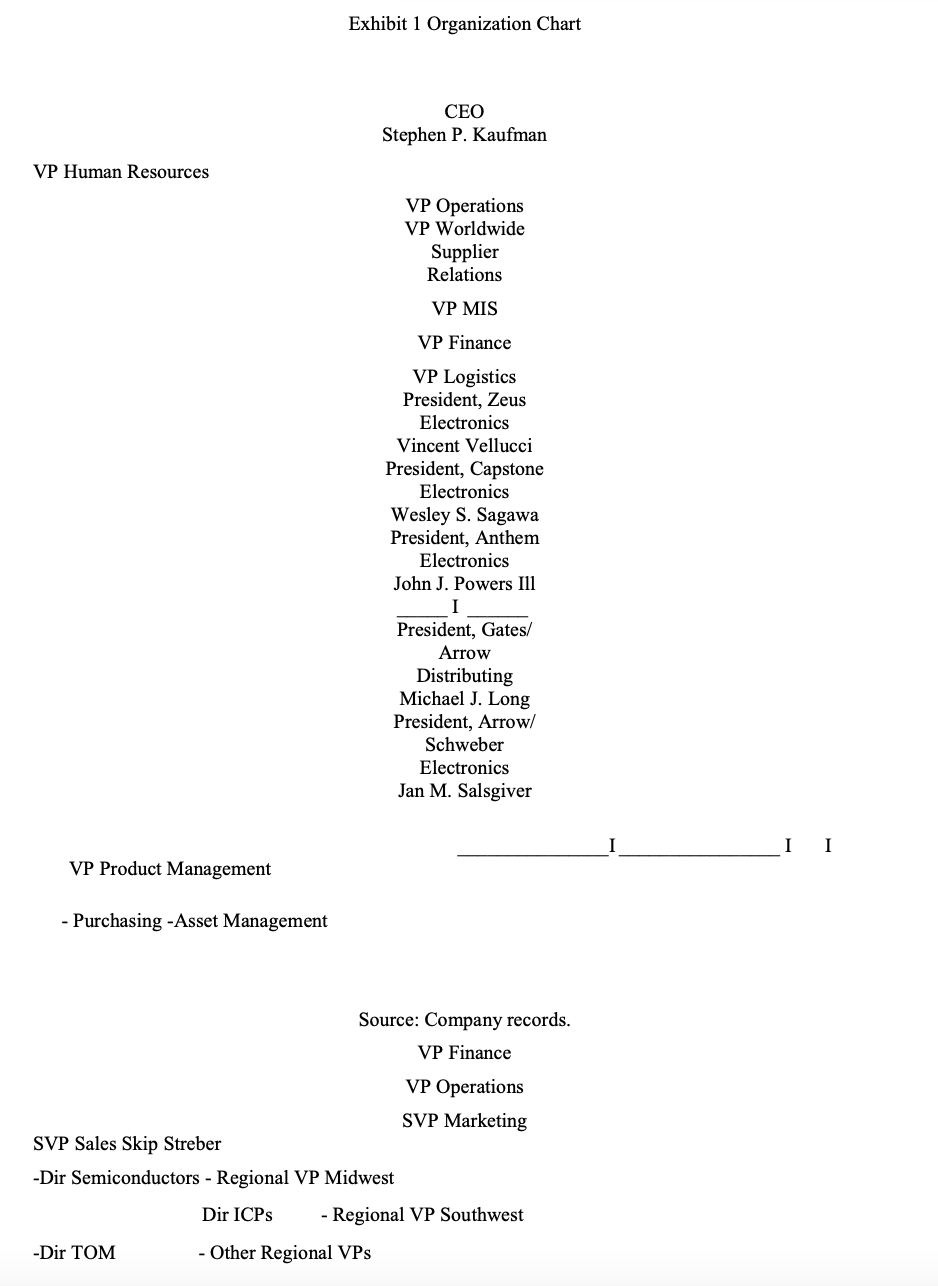

Note that Exhibit 7: talks about cannibalization of BAS business only. The 601 million in the last column - includes BAS transactions and BAS relations. It is not reflective of ALL transactional customers or any VA customers.

We have to, therefore proceed with the notion that 40% of BAS relations and 100 of BAS transactions will switch under a pessimistic scenario.

Therefore, the split of total sales into the 4 quadrants is necessary. Something like this:

Base case scenario is easy:

Gross margin= (1.443b X.125) +.(867X.225)/2.31 b = 16.23%

Now work out the optimistic scenario: where 100% of BAS transactionals will be subjected to a lower

margin of 16.5%

And under a pessimistic scenario 100% of BAS transactionals and 40% of BAS relationals will be facing a reduced margin

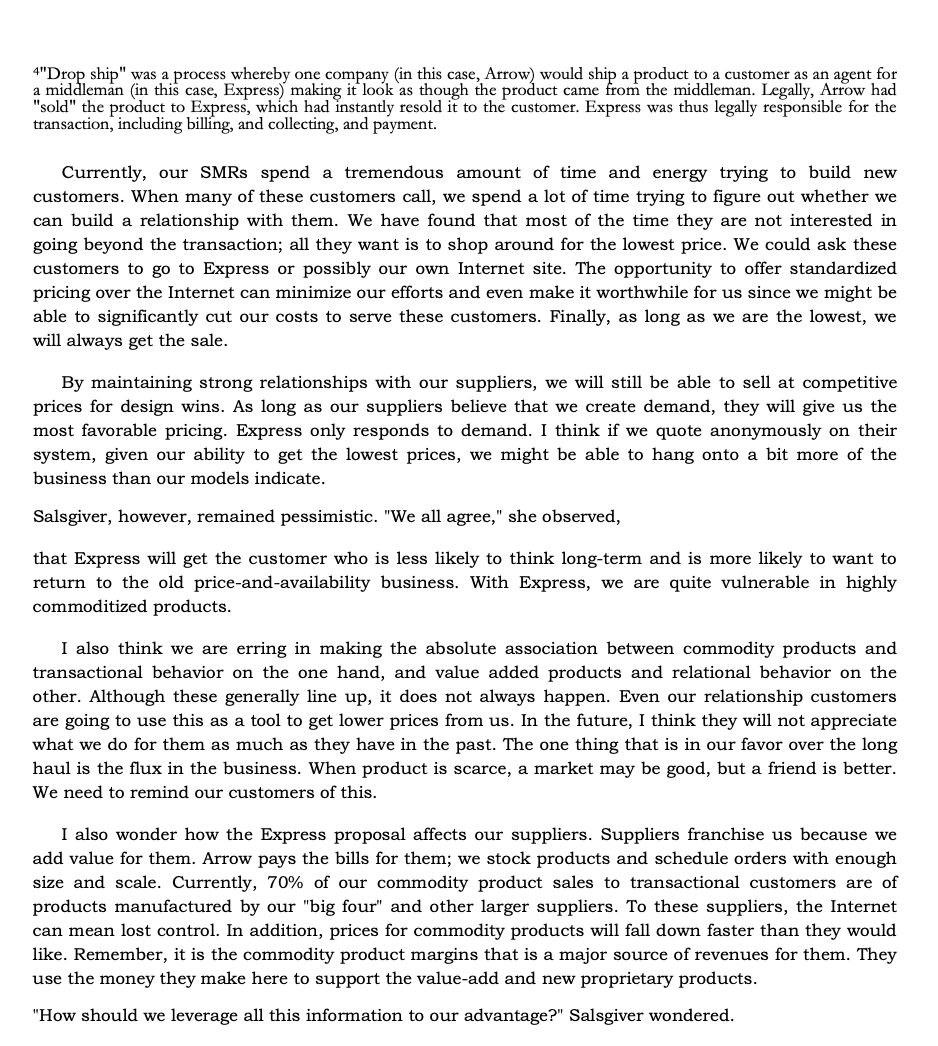

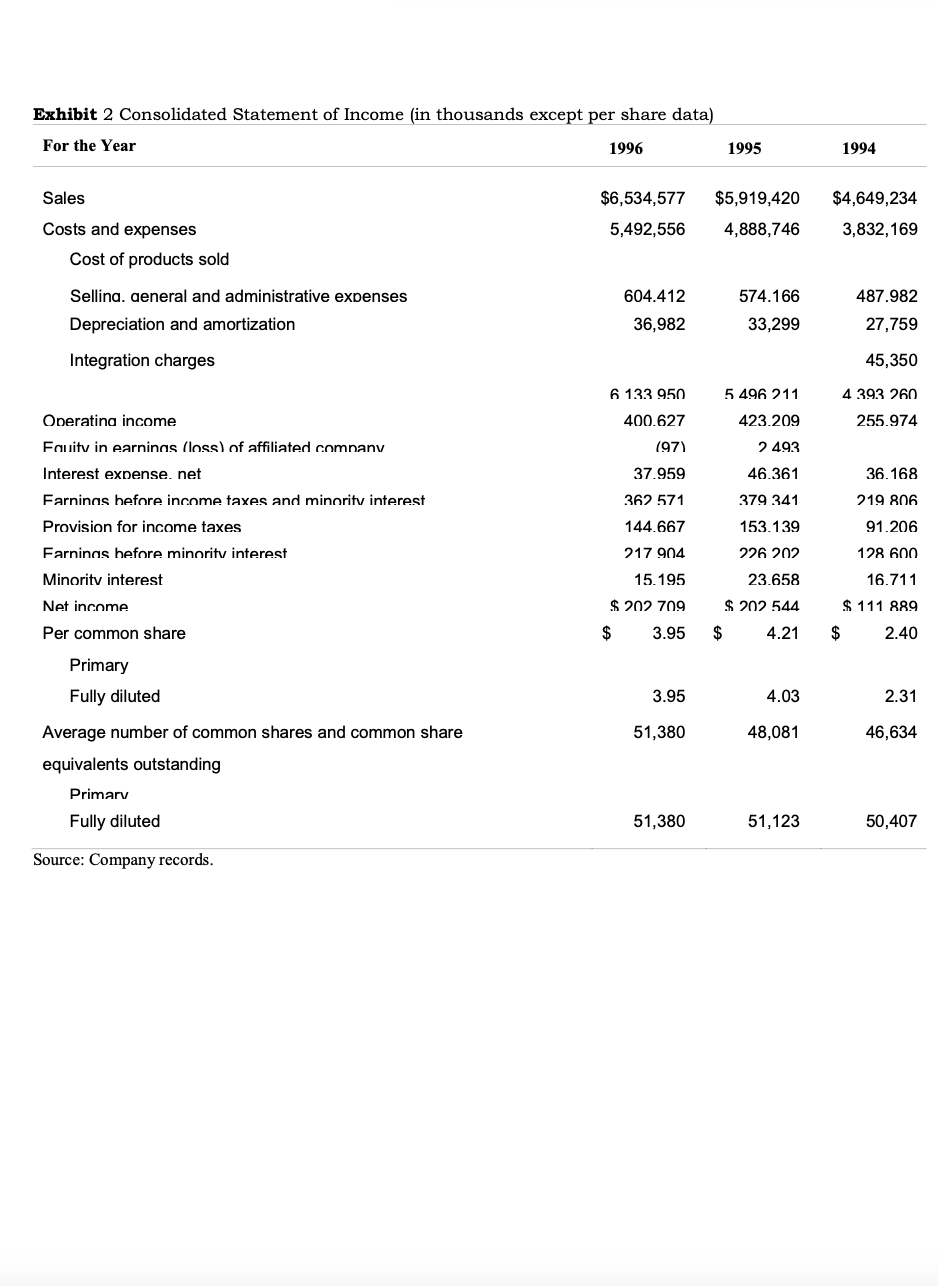

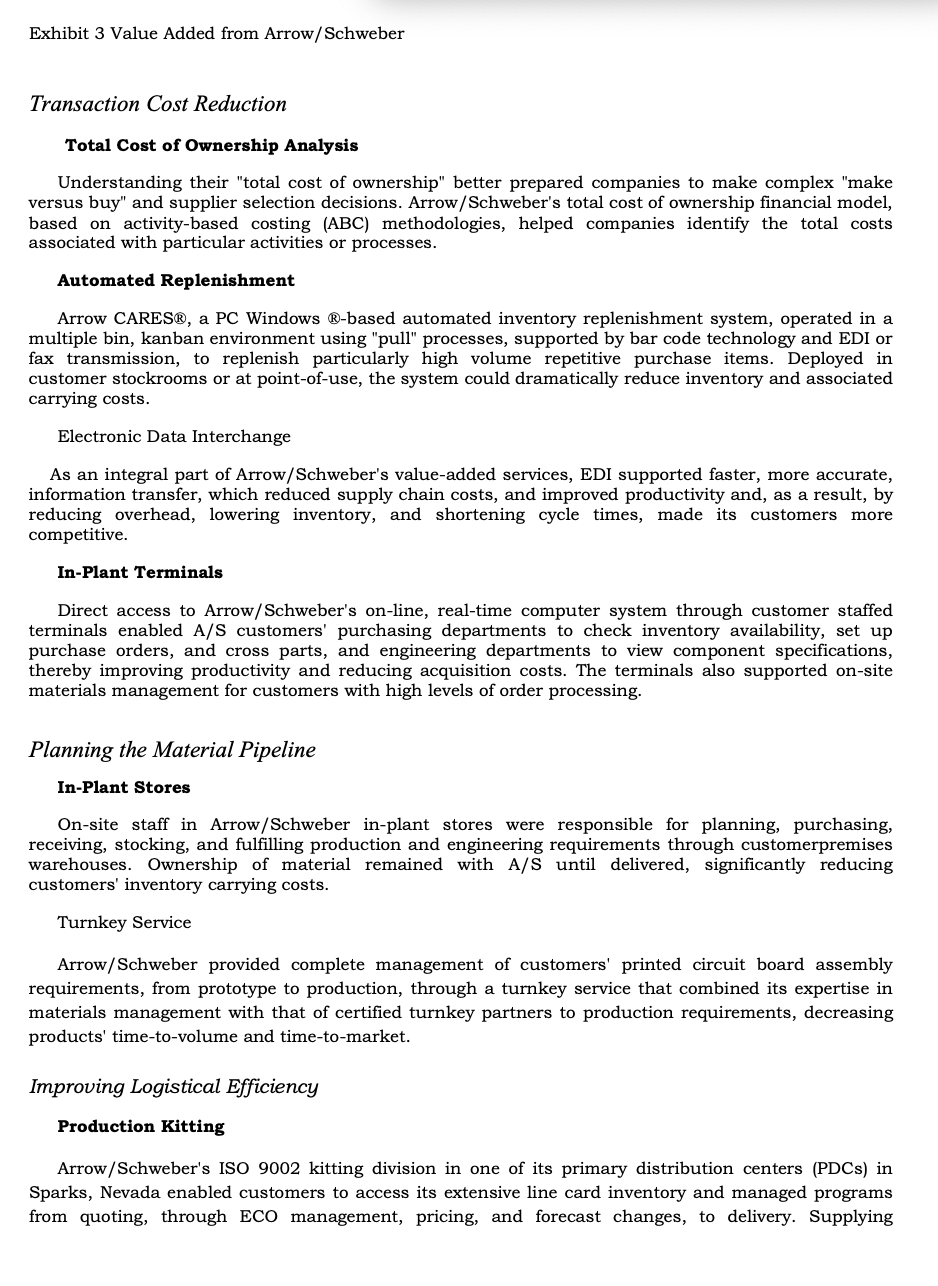

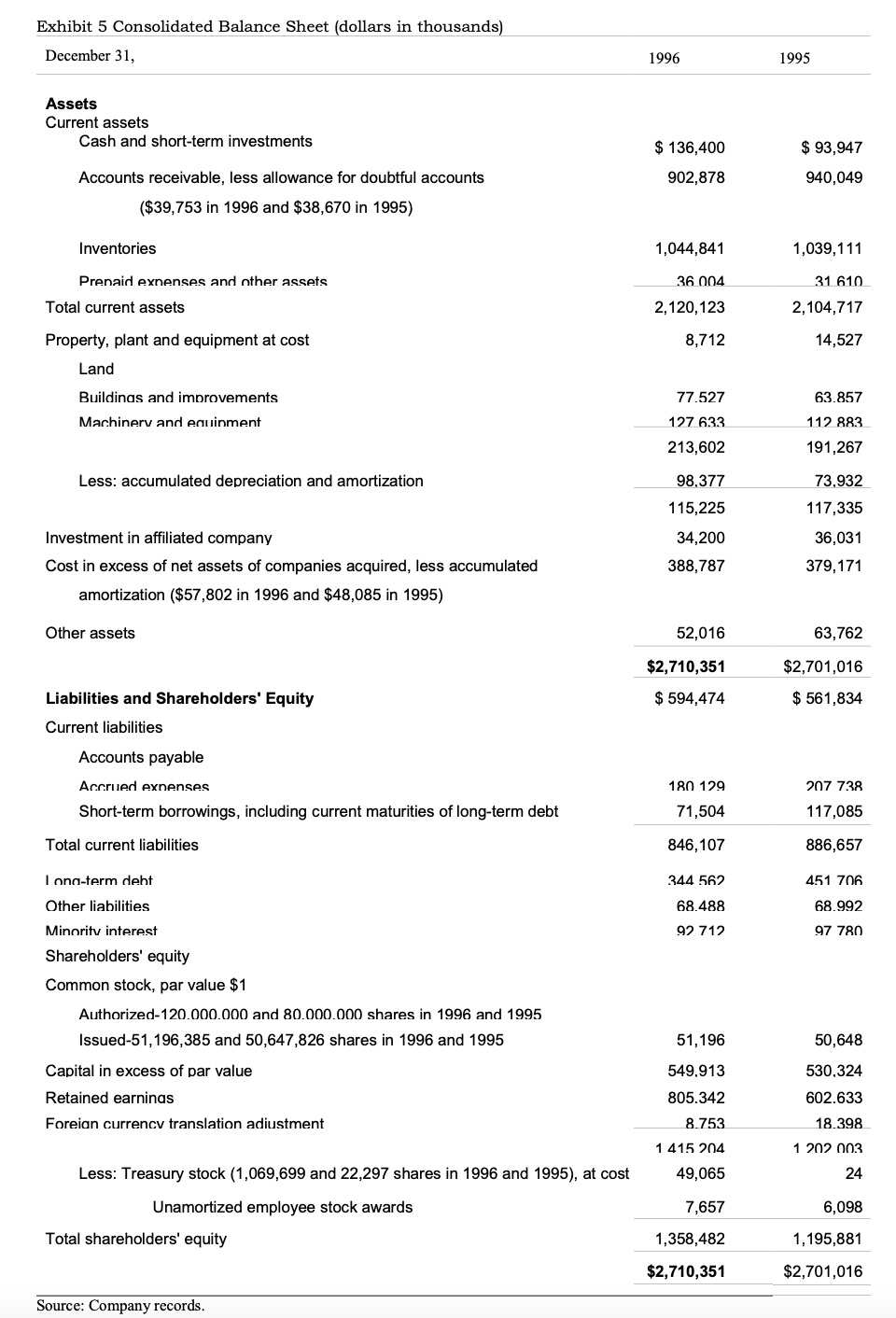

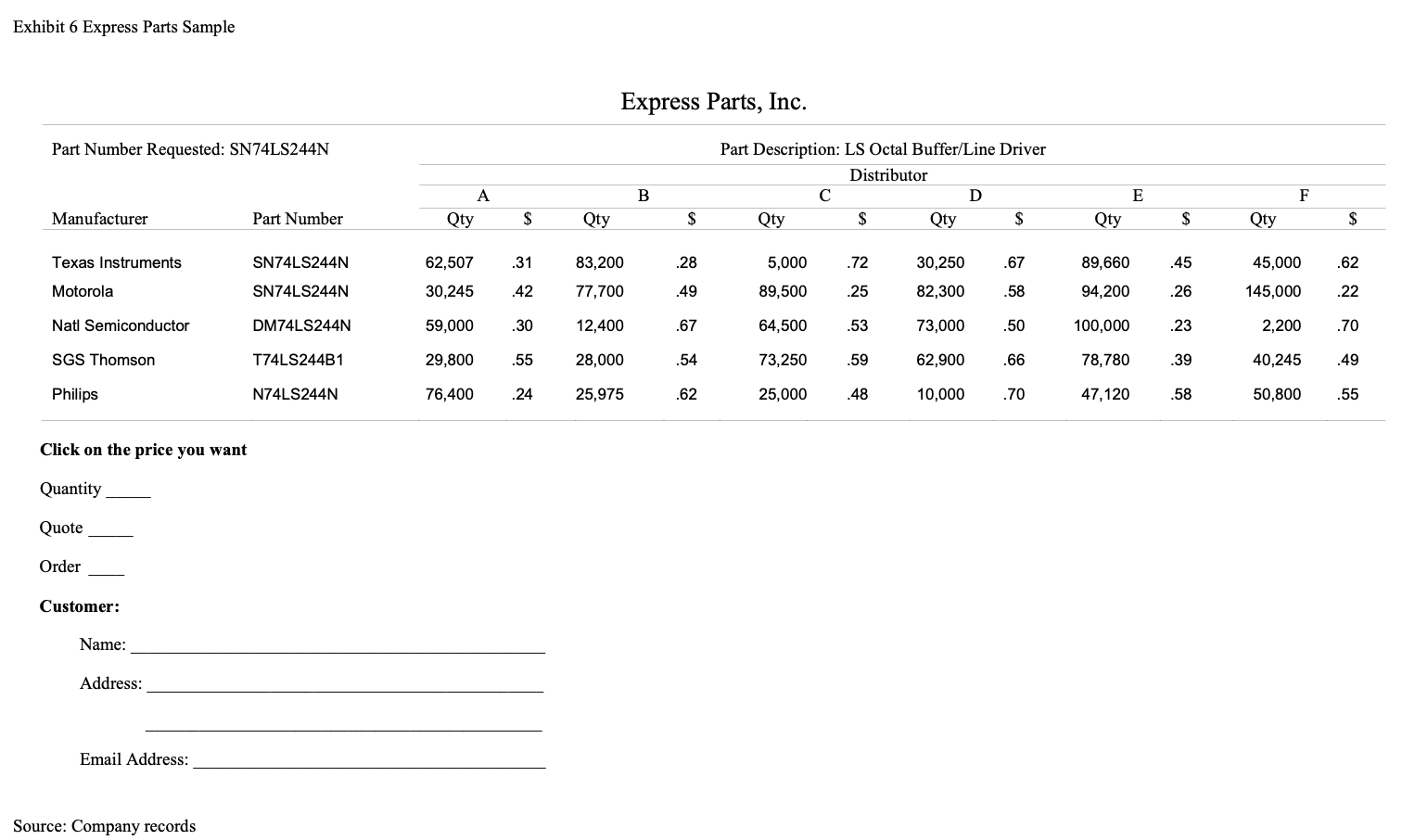

Arrow Electronics, Inc. Jan Salsgiver, president of the Arrowachweber [AfS) group, a subsidiary of Arrow Electronics, reviewed the Express Parts Internet Distribution Service proposal with colleagues Skip Streber, AIS senior vice president for sales, and Arrow CEO Steve Kaufman [see Exhibit 1]. Express had developed an Internetbased trading system that would enable distributors to post inventories and prices to a bulletin board giving customers large and small an opportunity to shop for prices. The opportunity to quickly gain new customers had to be traded off against potential effects on Arrow's relationships with current customers, who might exploit Express's bulletin board to cherry pick products from different channels. Arrow's relationships with its suppliers might also be affected. If they came to view Express as a legitimate option, its suppliers might disintermediate Arrow from their distribution channels.1 "As a distributor," explained Salsgiver, we need to know three things: how we create value for our customers for the prices we charge; how this value is different from what our suppliers can provide to our customers; and whether rms like Express can offer the same value or more for lower prices. We have a successful business model that is based on a portfolio of products and services that we offer our customers. Our customers come back to us because they get the most value from us for the prices they pay. If Express is going to change this equation, then we need to adapt our business model to accommodate the changes. Salsgiver realized that before she could make a decision on the Express proposal she needed to answer a number of questions, among them: How many of A; S's customers were likely to switch some of their purchases to Express? How would this affect A)\" S's sales and profitability? How would A} S's suppliers react to Express? Finally, was Express a threat to or an opportunity for A; S? Arrow Electronics It was common for semiconductor and electronic component manufacturers such as Intel and Motorola (hereafter referred to as suppliers] to deal directly with large original equipment manufacturers [0EMs]. Typically, sales to these customers accounted for 65% to 75% of the suppliersr sales. Suppliers franchised small numbers of distributors such as Arrow Electronics to manage sales to the remaining customers that they could not serve directly, whether because of diminutive size or extensive service requirements. Arrow Electronics was a broadline distributor of electronic parts, including semiconductors and passive components. Founded in 1935 to sell radio equipment, the company had undergone a number of major changes. Three Harvard Business School graduates who acquired a controlling interest in the company in 1968 had by 1980 grown it to the number two position, largely through acquisitions. A hotel re in December 1980 that claimed the lives of ve of the company's top six ofcers and eight other Arrow executives was followed by a shaky regrouping that coincided with an economic recession. Under the leadership of Stephen Kaufman, who became president in 1982 and CEO in 1986, Arrow once more began to climb, reaching the number one position among electronics distributors by 1992. Consolidation throughout the distribution world resulted in a small number of large companies to capturing the top tier of the market by 1997'. Arrow's closest competitor in 1996, Avnet Inc., trailed it by more than 20% in sales although it had grown by 14% compared to Arrow's 10% during that year. Of the next group of competitors the largest, which included foreign entrants Rabb Karcher and Future Electronics as well as longtime rivals PioneerStandard, Wyle, and Marshall Industries, was one quarter the size of Arrow in total sales volume and earned less than Arrow's largest operating group. Turning in a solid performance in a less than solid market, Arrow had earned more than $6.5 billion in sales in 1996 [Exhibit 2 presents nancial information for 19941996]. Arrow's North American operations were headquartered in Melville, N.Y (see Exhibit 1]. Sales and marketing functions were divided among ve operating groups, distinguished by product and strategy, individually responsible for asset and materials management and P&L. Three groups, Arrow;f Schweber, Anthem Electronics, and Zeus Electronics, sold semiconductors to different customer bases, Zeus to military and aerospace customers, Anthem and A} S to industrial customers. The other two groups were productdriven, Gateszrrow Distributing selling primarily computer systems, peripherals, and software, Capstone Electronics passive components. Arrow/Schweber Arrowachweber, the largest of Arrow's working groups, had sales of $2.07 billion in 1996. AIS president Jan Salsgiver, who had taken the helm in 1995, was leading Af S towards higher levels of technological expertise through technical certication of its eld sales representatives and dedicated investments in product management. Af S's local operations were congured in a branch structure. Headed by a general manager, each branch included eld sales and inside sales representatives, product managers, and eld application engineers, as well as administrative personnel and additional managers as necessitated by size. Six regional VPs oversaw A} S's 39 branch managers. Products and Suppliers The Arroijchweber line card (i.e., the set of products for which AIS was a franchised distributor] comprised two chip categories: standardized and proprietary. Standardized chips were interchangeable and produced by multiple suppliers, proprietary chips manufactured by a single supplier. Only franchised distributors could sell suppliers' standardized or proprietary products. In an industry in which the top ten suppliers provided 80% of the products on distributors' line cards, A; S's supplier list was long, numbering 56 suppliers in the spring of 1997 and growing. Among A] S's largest suppliers was Altera, a manufacturer of proprietary programmable logic devices {PLDs} that required considerable value-added programming. As was typical in the industry, the manufacturer did virtually no programming. Roughly 20% of Altera's products were purchased directly by customers who had inhouse programming skills. Altera sold the remaining 80% through two franchised distributors capable of providing the valueadded programming required by individual customers. Another large A; S supplier, Intel, also supplied mostly proprietary semiconductor products, although its most popular line, the x86 chip, did not require the level of valueadded programming and engineering support that A] S provided for Altera's PLDs. Texas Instruments and Motorola, the remaining two of AfS's "big four," balanced the line card by selling a 75 f 25 mix of standardized and proprietary products. customers A; S's traditional customer base of mid and smallsized original equipment manufacturers {OEMs} accounted for 56% of sales in 1996. These customers were too small for the suppliers to serve directly. Suppliers therefore engaged franchised distributors, to which they offered limited return privileges and price protection, to consolidate and satisfy demand from these customers. Franchised distributors afforded customers the opportunity to order in small quantities and with short lead times, accommodations suppliers were unwilling to provide. With suppliers having chosen not to support credit management for customers, it fell upon distributors to offer this benefit as well. In addition to carrying massive inventories, distributors also performed value added services for customers who needed, for example, to receive all products needed for a specic manufacturing run in a single shipment or to release products to shipment based on forecast rather than previously entered, firm purchase orders. "This is very important to customers that have adopted JlT procurement systems," Kaufman explained. l1These customers want to be very sure that they have everything they need at the right time and in the right quantities. If not, they run the risk of having to stop their production lines." Distributors' upto theminute knowledge of available products could also be extremely valuable to OEMs in designing equipment for manufacture. liken OEMs large enough to purchase direct often found distributors' valueadded services attractive. "When customers get large enough," Salsgiver explained, they want to buy only direct from suppliers, who can provide them with the technical support and low prices they want. As time passes, however, these customers begin to reach a stage where they want to hand off materials management as well. Most suppliers are not capable of providing this service and, more important, are not interested in getting into this business. They don't want to take on any activity that does not have the high margins that electronic parts and components usually provide.2 At this time they can become good distributor customers. A second and growing new market was the Contract Manufacturer {CM} business, which produced circuit boards and industrial computer systems for OEMs. OEMs would outsource production of prototypes or even entire product runs to CMs, which would procure the components and assemble products. The CM business had grown at 30% per year between 1992 and 1996. During the same period, the percentage of business A; S channeled through CMs grew as well, reaching 20% of total sales by 1996. "Five years ago," observed one AfS eld sales representative, the only CMs were small momandpop operations used for overow or testing demand. A few of them have grown to be multibillion dollar enterprises. However, there still are a large number of mid and smallsized CMs. CMs tend to be very price sensitive. They selectively use our value added services such as programming and supply chain management in addition to our quick delivery service. But they don't need our engineering services at all. AIS served two other major customer segments. Customers that purchased Intel x86 chips exclusively to manufacture PC clones accounted for 11% of A} S's business. The principal value AfS offered these customers, which were differentiated from traditional OEM customers in that they purchased in a purely commoditized fashion, was credit, which was unavailable to them through suppliers or other nancial institutions. The nal segment comprised customers that purchased entire systems or assemblies. "These," Streber explained, "are computer product subassemblies that are used as components inside industrial equipment such as elevators or medical equipment. For example, the heart of a blood gas analyzer is an Intelbased PC that we supply. These customers tend to order in smaller quantities and need highly customized solutions." AfS' Relationship with Suppliers To a far greater extent than in most other industries, electronic component manufacturers relied on distributors to generate demand. This tendency, according to Salsgiver, was a function of the nature of the electronics business. "Suppliers have two needs from us," she explained. They need us to win business in their standardized products to help them grow and gain both prot and market share. They also need us to represent their new technologies and proprietary products to our customers. It's obviously critical for both of our future success to help customers design our suppliers' new proprietary devices into their products. "Our relationships with our suppliers have two unique components," continued Salsgiver, First, suppliers franchise select distributors to sell their products and provide nancial incentives such as price protection and limited return privileges to only these franchised distributors. More pointedly, suppliers refuse to honor warranties of products purchased through channels other than the ones they have designated. Second, many suppliers ship their proprietary and standardized products to us at list price or marginally below it. For example, one of our suppliers sets our book cost at a constant 5% below their list price. When we get a request for a price quote from a customer, we call the supplier back and give them the details of the customer and the opportunity. The supplier then decides how much of an additional discount they will provide us on this request. In this manner, they know exactly what we are doing and they are also able to control prices. The level of discount provided varies depending on whether it is our design win or a jump ball [see below]. Design Win Af S, like other electronics distributors, generated demand by helping customers engineer end products to which its suppliers' chips were integral. Suppliers tracked which distributors did design work by assigning nunlbers to specific distributorcustomer partnerships. "When we start working on an opportunity and invest resources in a customer's project," explained Streber, we will call our supplier and give them all the details. The supplier then assigns a design number that recognizes the work we have done. This is called "design registration." When the order materializes and the customer shops across distributors for price, the supplier offers a much higher discount to the distributor credited with the design registration as compared to any other distributor. Unless another distributor is willing to take a hit they will not be able to serve this customer, since only the distributor with the design registration will be able to earn an acceptable margin at the suggested resale price. Jump Bali Customers that purchased on the basis of manufacturer reputation or price and did not involve a distributor in design work were termed "jump balls" in the business. For these customers, suppliers offered all distributors the same margin, which was signicantly less than that which would be offered in the case of a design win. Jump balls also occurred when a customer switched from direct purchasing to distribution. "In these cases," Salsgiver explained, "the suppliers have already created the demand for the products by doing the design work themselves, so they see the distributor's value only in credit and fulllment and they compensate minimally for these services." Managing the Relationship with Suppliers "Our suppliers are able to control our destiny in many ways," observed Kaufman. In the case of jump balls, our suppliers inform the customer about the various distributors they can buy from. Suppliers usually don't exclude a distributor from the list. But they do control the order of names. This is an important factor. Being the rst name on that list increases the chance of getting the sale. It is the supplier's way of rewarding one distributor over another. Another way suppliers manage demand flow is in the order in which they inform the distributors about an opportunity. Getting to know about an opportunity even a few minutes or hours before anyone else can give our sales reps all the time they need to secure the sale. Finally, suppliers can manage the ow of orders by managing the time they take in responding to a distributor's request for prices. The norm is that the supplier needs to get back within 24 hours of a request. If you have a good relationship or if the supplier wants to reward you, you might get a response a lot faster. If you are not in the good graces of the supplier, you could be the victim of an overloaded sales rep who was so busy that it took all of 24 hours for them to process your request. This does not mean that we have no power. Usually, for the standardized products we carry lines from different suppliers that have identical specifications, and therefore are substitutable. When a customer needs standardized products, we can go back to each supplier and literally shop the volume around to see who will give us the best margins. Typically these are high volume products and therefore an important part of the suppliers' portfolio. A supplier that is anxious to ll its production lines can "buy an order." This leads to higher margins for us. Here is when, depending on how we have been treated, we can return favors. If suppliers use jump balls to keep distributors in check, we are able to use design wins and competitive standardized products to counterbalance their power. "Suppliers want A] S and other distributors to get technology into the hands of the right customers," added Salsgiver. In this business, demand points are not always known. An operation in someone's garage this year could be the multibillion dollar giant ve years from now. Our suppliers want us to identify these growth opportunities and lock them in before anyone else does. Our job at A} S is to know our customers well enough to create demand for our suppliers' products. We maintain a separate account development group that calls on small companies looking for opportunities of the future. This is our ace of spades when it comes to managing our relationships with our suppliers. Arrow's Selling Effort "It is important to understand how products are viewed by our suppliers and our customers." Salsgiver explained, "When we deal with our suppliers it is the world of standardized and proprietary products. When we deal with customers, it becomes a world of book and ship, and valueadded products. " Book: and 5&1) (BAJ) AIS had developed a realtime, online computer system that tracked costs, prices, and movements of 300,000 inventoried part numbers and order patterns [AI S processed more than 10,000 transactions per day] and sales history for each of the company's 50,000 customers. Using terminals connected to this system, AI S's 300 branchbased sales and marketing representatives [SMRs] handled daily phone calls from customers checking delivery, availability, and price levels. For customers who requested a quote directly, an SMR might try to secure the business and arrange to ship the product. This was termed a book and ship [HAS] transaction. SMRs exercised pricing authority, obtaining discount levels from suppliers and quoting prices to their assigned customers on the basis of their knowledge of customers' buying patterns, local market trends, current cost levels, and inventory on hand. AIS commonly referred to BAS products as commodity products because of the nature of value added by AIS. AIS' gross margins on BAS products ran above the company average, in the range of 20% to 25%. Valve Added (VA) Alternatively, an order might be originated by field engineering and facilitated by a eld sales representative (FSR), the typical design win situation. In this case a customer's purchasing agent would speak to an SMR only to nalize the details of the transaction. Such transactions represented the 400 FSRs visited their customers' [usually 1020 per FSR] design engineers to learn about current projects and explain and promote new products being introduced by Arrow's suppliers. FSRs also established relationships with customersr purchasing personnel, negotiated major contracts, and resolved problems with the ow of orders and deliveries. FSRs worked hand in glove with the eld application engineers (FAEs) who provided technical support to the sales force, assisting with problem solving and product design issues. Suppliers that wanted Arrow to help smaller customers designin their proprietary parts also relied heavily on the FAEs, who were salaried and generally expensive to maintain. Product managers [PMs] advocated on behalf of manufacturers by ensuring that FSRs and SMRs were uptodate on suppliers' latest products and marketing programs and that the sales force was meeting its supplierbysupplier sales budgets. PMs also followed up on leads and referrals from suppliers and worked with Arrow's corporate marketing department to ensure that lowvolume and unusual products were ordered on a timely basis. Streber pointed out that customer involvement to a great extent revolved around the prevailing understanding of value added. "The meaning of value added has continuously changed in our business,'I he explained. In 1977 value added meant nothing more than providing an inventory buffer for the customer. In 1987 it meant altering components to meet customer needs, either by programming, packaging, or kitting parts3. In 1997, for our most important customers, it meant building virtual organizations with us through inplant stores and the like. Today, the true value added is in order cycle management. In 1977 about 2% of our sales had a valueadded component. By 2000 this number can reach as high as 80%. [See Exhibits 3 and 4.] Phantom Inventory One result of the system of debitstocost employed by suppliers was what Salsgiver termed "phantom inventory." [Exhibit 5 presents Arrow's overall inventory gures.) "As strange as it sounds, the way our business works," she explained, "we buy product all day long at a dollar per part, sell it at sixty cents, and make a decent prot.II The way suppliers managed pricing resulted in distributors paying a relatively low gure for inventory carried on the books at high cost. But because it made it look as though inventon never turned, this system made daytoday management, not to mention projections, quite difcult. Relationships with Customers Customers that placed requestsforquotes [RFQ] for one or a few products with a number of distributors simultaneously were termed I'transactional" customers. The distributors would obtain current pricing information from their suppliers and respond to RFQs, whereupon the customers might pursue subsequent rounds of negotiations to obtain the best price. SMRs expressed ambivalence about transactional customers. I'I spend a good portion of my day speaking to these sorts of customers,'I explained one. "They always know the current prices and will list grey market distributors' prices when I give my quote.'I Added an FSR who called exclusively on CMs: We are currently able to provide credit and short delivery lead times on small orders to contract manufacturers, which they cannot receive either from the suppliers or from the non franchised distributors otherwise known as brokers. This means that when an OEM asks a CM to build a board, the CM has an incentive to purchase through us. But CMs can design in our manufacturers' products just as easily as we can. If our suppliers decide to reward CM demand creation the way they reward such distributor activities, then it's going to be really tough to compete. Observed Kaufman: Roughly 25% of our sales today come from transactional customers. Typically, a majority of these sales are of the bookandship (BAS) type. We cannot afford to ignore this group for several reasons. In addition to accounting for a signicant portion of our current sales, this customer segment is also a major source of relationship customers in the long run. Most of our relationship customers today started out as transactional customers. Customers want to check us out and monitor our performance over several orders before they are willing to get into any sort of agreement that goes beyond the transaction level. We are generally able to convert at least half of our transactional customers into relational customers over the long haul. Other customers attempted to establish longterm relationships with a small number of distributors. Explained Salsgiver: Most of our relationship customers do more than half of their business with their top distributor. These customers want the convenience of submitting an entire bill of items for a quote, nding it more valuable to have a steady partner than the rock bottom price over the long haul. That doesn't mean that they don't care about prices. It is very common for them to maintain a relationship with one or two other distributors in order to ensure continuous availability of products and to keep their primary distributor in check. Most of our relationship customers buy a basket of products from us that includes BAS and VA products. Given the competitive nature of this business, we have found that it is difcult to get close to a customer through the bookandship business. Our approach is to use the valueadd products as the rst step to building a relationship. We provide customers with the bestinclass support in this category. Once customers get a chance to interact with us, they are able to see the true benet of doing business with us rather than any other distributor. Now comes a peculiar trait in our business. You would expect that the customer pays us high prices for the valueadded services we provide. Well, that doesn't happen. The customer knows that there are several distributors that can provide these valueadded services. They then use the threat of switching to other distributors to make sure that we don't charge too much of a premium for our services. While we try to demonstrate tangible nancial benets to justify our prices, there are times when we practically give away the value that we create for them and recover our prots in other areas. Although the margins on the chips are the same as in our BAS business, because we do not charge adequately for our value added services, our gross margins on valueadd products run below the company average, in the range of 10% to 15%. We crosssell our other products to these customers by offering them signicant breaks on the valueadd products in return for their commitment to buy the bookandship products exclusively from us. In a way, in these relationships the commodity products subsidize the specialty products. Finding the right customers with which to develop longterm relationships was extremely important. It was not uncommon for customers simply not to appreciate the work done by Af S or even to honor their own commitments. "We had been pursuing a prospect for some time," recalled Martha Moranis, an SMR, when a request came in from them for a highly allocated proprietary chip manufactured by one of our major suppliers. We saw this as a great opportunity to break into the account and establish a longterm relationship and we agreed to obtain this product for them at a favorable price. In return, they promised to purchase one of their major needs exclusively from us at a price that allowed us a good margin. We jumped through arning hoops to deliver on our side of the bargain, but once they had received their shipment they seemed to change their mind about the agreement. When it came time for them to place their standing order, they tried to lower the price we had agreed upon and nally placed the order with another distributor. We could not do anything with the supplier because they saw it as a jump ball. In hindsight, we would have been better off not serving this customer at all. The same set of actions on our part will get a very different response from some of our good customers. We have found that the best way to strengthen a relationship that is already strong is by helping our customers in their times of need. Our good customers will always remember what we did for them and usually reward us at a later date. Viewed from the other side of the fence, longter'rn relationships represented a signicant obstacle. Explained one FSR: I once called on a customer who had a gatekeeper for a purchasing manager. This buyer had been there for fteen years and had fallen into a routine of placing the same orders with the same distributors all the time. For some reason he did not want to deal with us. We rotated this account through some of our best reps with no success. This buyer was "antiArrow" and we had no clue why. We tried to go around the buyer and work with engineering. This made things worse for us. The buyer told us that we could not design in any product that they currently purchased through our competition. This made it really tough to maneuver. Our chance arrived when a new buyer came in. This buyer was willing to work with us and we ended winning signicant amounts of business from this customer. This process can work in reverse as well. We can establish a solid relationship with a customer that is utterly obliterated when a new buyer with a different set of comedians replaces the person with whom we used to work. llThere is another angle to building a relationship with a customer," observed Kaufman. I think we need to go further to make the relationship virtually unbreakable. We need to get the customer to invest along with us in systems and processes that enable us to provide valueadded services. It is easier for us when we are dealing with valueadded products like PLDs where the customer has to have invested in productrelated systems and processes that are customized to match our programming skills. The trend toward greater demand for valueadded services is our best bet to counterbalance the high price sensitivities of our customers and the relational "cheating'I that takes place in our business. But even with commodity products, where there is little that can be done at the product end, a customer that invests in supply chain management initiatives along with us is very unlikely to terminate their relationship with us. AIS and the Internet During the early to mid1990s many electronics distributors established homepages on the Internet through which to present their companies, provide line card infonnation, and even sell products. The prominence of independent, nonfranchised distributors, viewed by many franchised distributors and customers alike as being less than legitimate, was unmistakable in the move to the Internet. These companies purchased products from others' overstocks, but, lacking authorized reseller agreements, they could not offer the manufacturers' warranties. Although it had established a closed system that enabled its customers to obtain xed price and availability information from terminals in their plants, Arrow had been reluctant to establish a presence in the public domain, preferring, instead, to watch and wait while others tested the waters. Homepages were eventually established for the company and its operating groups, but these websites did not incorporate purchasing capability. Rather, they functioned as information centers, sources of material about suppliers, searchable lists of parts, and news. Potential customers were directed from the webpage to the national 1800 number for a specic group. Express Parts, Inc. Express Parts, Inc. was a new independent distributor that developed an Internet-based trading system around a multidistributor bulletin board. Express claimed that its search engine could quickly crossreference equivalent parts from multiple manufacturers based either on part number or technical description and estimated that more than 50,000 OEMs throughout the United States would have access to the service. Express proposed that access to such a large market would enable A] S to increase sales at less than half the cost of doing so via its branch network. Express's program was to work as follows. 1. A] S's full list of available inventory and associated prices, transmitted to Express nightly, was to be combined with similar lists from a limited number of other distributors. 2. Express's customers would sign onto its service via the Internet and search by part number or description. Upon making a selection, a customer would view a screen displaying all products that matched the search criteria, together with prices and quanties available for shipment [individual distributors identied only by an arbitrary letter, not by name]. (See Exhibit 6.] 3. A customer could select any supplier] distributor combination, enter the quantity desired, and click the mouse to place the order, which would instantly be transmitted to Express. Express would review the order, perform a credit check, and acknowledge accepted orders to the customer and route them electronically to the appropriate distributor. 4. Distributors would, on behalf of Express, pick parts and I'drop ship" orders directly to customers, notifying Express electronically that shipment had been made.4 Express billed customers. 5. Payment, minus Express's fee of 6%, was made to distributors 30 days after orders shipped. Decisions Express's proposal had stirred signicant debate among the A} S management team, which had now been discussing it for nearly a month. Express had told Salsgiver that they needed a decision within the week. This was, they said, because they were only going to ask a limited number of distributors to join, in order to avoid having too many duplicate and competitive lines. Kaufman had asked Salsgiver to evaluate the impact Express might have on AfS's business under diHerent scenarios. "We need to have some idea of what this is going to do to our business," he had told her. Salsgiver had subsequently commissioned a detailed study of two specic outcomes. In the optimistic scenario, all transactional customers were assumed to switch their purchases from AIS to Express. In the pessimistic scenario, all transactional customers and roughly 40% of relationship customers were assumed to switch their purchases from A] S to Express. These percentages were arrived at through a detailed bottomup account analysis. [Exhibit 7 details the results of this study.) Realizing that the analysis provided some direction, but not all the answers she needed to make her decisions, Salsgiver reected on how two of her colleagues had weighed in on the issue. "It is very important that we keep in mind our corporate objectives," Kaufman had emphasized. With expenses at 11%, we cannot afford our overall gross margins for AfS to fall below 15%. We certainly don"t want to accelerate the downward trend in margins that we've been seeing any more than is necessary. I think the Internet will never be anything more than an invitation to bargain. In the worst case scenario, all our current customers will get the lowest price from the Express system and use it as a starting point to bargain with us. I have yet to meet an industrial buyer who does not believe that he can do better by bargaining, especially on a price open to the public. With Express as a competitor, I think we will have to learn how to sell against "going out of business" prices on a regular basis. We also have to have a much stronger valueinuse sales story than ever before. "I agree," Streber had concurred, that any time the only value A] S brings to the table is in price and delivery, we are vulnerable to the Internet for competition. My feeling is that we will lose little or none of our business with relationship customers and about half of our business with transactional customers. But if we do it right, this loss will be more or less compensated for by the additional business we get from Express. Express gives us the opportunity to sell to those customers that we cannot sell to using our current business model. 4"Elto ship" was a process whereby one company (in this case, Arrow) would shi a product to a customer as an agent for a mid eman (in diis case, Express} making it look as drough the product came m the middleman. Legally, Arrow had I'sold" the product to Express, which had 1nstantly resold it to the customer. Express was thus legallyr responsible for the transaction, including billing, and collecting, and payment. Currently, our SMRs spend a tremendous amount of time and energy trying to build new customers. When many of these customers call, we spend a lot of time trying to gure out whether we can build a relationship with them. We have found that most of the time they are not interested in going beyond the transaction; all they want is to shop around for the lowest price. We could ask these customers to go to Express or possibly our own Internet site. The opportunity to offer standardized pricing over the Internet can minimize our efforts and even make it worthwhile for us since we might be able to signicantly cut our costs to serve these customers. Finally, as long as we are the lowest, we will always get the sale. By maintaining strong relationships with our suppliers, we will still be able to sell at competitive prices for design wins. As long as our suppliers believe that we create demand, they will give us the most favorable pricing. Express only responds to demand. I think if we quote anonymously on their system, given our ability to get the lowest prices, we might be able to hang onto a bit more of the business than our models indicate. Salsgiver, however, remained pessimistic. "We all agree," she observed, that Express will get the customer who is less likely to think longterm and is more likely to want to return to the old priceandavailability business. With Express, we are quite vulnerable in highly commoditized products. I also think we are erring in malcing the absolute association between commodity products and transactional behavior on the one hand, and value added products and relational behavior on the other. Although these generally line up, it does not always happen. Even our relationship customers are going to use this as a tool to get lower prices from us. In the future, I think they will not appreciate what we do for them as much as they have in the past. The one thing that is in our favor over the long haul is the ux in the business. When product is scarce, a market may be good, but a friend is better. We need to remind our customers of this. I also wonder how the Express proposal affects our suppliers. Suppliers franchise us because we add value for them. Arrow pays the bills for them; we stock products and schedule orders with enough size and scale. Currently, 70% of our commodity product sales to transactional customers are of products manufactured by our "big four" and other larger suppliers. To these suppliers, the Internet can mean lost control. In addition, prices for commodity products will fall down faster than they would like. Remember, it is the commodity product margins that is a major source of revenues for them. They use the money they make here to support the valueadd and new proprietary products. "How should we leverage all this information to our advantage?" Salsgiver wondered. Exhibit 1 Organization Chart CEO Stephen P. Kaufman VP Human Resources VP Operations VP Worldwide Supplier Relations VP MIS VP Finance VP Logistics President, Zeus Electronics Vincent Vellucci President, Capstone Electronics Wesley S. Sagawa President, Anthem Electronics John J. Powers Ill President, Gates/ Arrow Distributing Michael J. Long President, Arrow/ Schweber Electronics Jan M. Salsgiver I VP Product Management -Purchasing -Asset Management Source: Company records. VP Finance VP Operations SVP Marketing SVP Sales Skip Streber -Dir Semiconductors - Regional VP Midwest Dir ICPs - Regional VP Southwest -Dir TOM Other Regional VPsExhibit 2 Consolidated Statement of Income (in thousands except per share data) For the Year 1996 1995 1994 Sales $6,534,577 $5,919,420 $4,649,234 Costs and expenses 5,492,556 4,888,746 3,832, 169 Cost of products sold Sellina. aeneral and administrative expenses 604.412 574.166 487.982 Depreciation and amortization 36,982 33,299 27,759 Integration charges 45,350 6 133 950 5 496 211 4 393 260 Operating income 400.627 423.209 255.974 Fruitv in earnings (loss) of affiliated comnanv (97) 2 493 Interest expense. net 37.959 46.361 36. 168 Farninas hefore income taxes and minority interest 362 571 379 341 219 806 Provision for income taxes 144.667 153.139 91.206 Farninas hefore minority interest 217 904 226 202 128 600 Minority interest 15. 195 23.658 16.711 Net income $ 202 709 $ 202 544 $ 111 889 Per common share $ 3.95 $ 4.21 $ 2.40 Primary Fully diluted 3.95 4.03 2.31 Average number of common shares and common share 51,380 48,081 46,634 equivalents outstanding Primary Fully diluted 51,380 51,123 50,407 Source: Company records.Exhibit 3 Value Added from Arrow;Ir Schweber Transaction Cost Reduction Total Cost of Ownership Analysis Understanding their "total cost of ownership" better prepared companies to make complex "make versus buy'I and supplier selection decisions. Arrow,f Schweber's total cost of ownership nancial model, based on activitybased costing [ABC] methodologies, helped companies identify the total costs associated with particular activities or processes. Automated Replenishment Arrow CARES, a PC Windows based automated inventory replenishment system, operated in a multiple bin, kanban environment using "pull" processes, supported by bar code technology and EDI or fax transmission, to replenish particularly high volume repetitive purchase items. Deployed in customer stockrooms or at pointofuse, the system could dramatically reduce inventory and associated carrying costs. Electronic Data Interchange As an integral part of Arrowachweber's valueadded services, EDI supported faster, more accurate, information transfer, which reduced supply chain costs, and improved productivity and, as a result, by reducing overhead, lowering inventory, and shortening cycle times, made its customers more competitive. In-Plant Terminals Direct access to Arrowachweber's online, realtime computer system through customer staffed terminals enabled A,r'S customers' purchasing departments to check inventory availability, set up purchase orders, and cross parts, and engineenng departments to view component specifications, thereby improving productivity and reducing acquisition costs. The terminals also supported onsite materials management for customers with high levels of order processing. Planning the Material Pipeline In-Plant Stores Onsite staff in Arrowachweber inplant stores were responsible for planning, purchasing, receiving, stocking, and fullling production and engineering requirements through customerpremises warehouses. Ownership of material remained with AIS until delivered, signicantly reducing customers' inventory carrying costs. Turnkey Service Arrowachweber provided complete management of customers' printed circuit board assembly requirements, from prototype to production, through a turnkey service that combined its expertise in materials management with that of certied turnkey partners to production requirements, decreasing products' timetovolume and timetomarket. Improving Logistical E'iciency Production Hitting Arrowachweber's ISO 9002 kitting division in one of its primary distribution centers (PDCs] in Sparks, Nevada enabled customers to access its extensive line card inventory and managed programs from quoting, through ECO management, pricing, and forecast changes, to delivery. Supplying prepackaged lcits to designated customer production facilities "justintime" helped to reduce stockouts, component obsolescence, inventory carrying costs, and other inventoryrelated expenses. Device Programming Arrowachweber customers not only offered customers the industry's broadest line card, but was also uniquely positioned through its comprehensive resource of silicon and design support to provide solutions for every PLD application. Four primary ISO 9002 certied programming centers linked to a single network provided an optimal means to match demand to capacity and speeded turnaround for customers. Customers that programmed through Arrowachweber avoided costly capital equipment expenditures and minimized product obsolescence resulting from last minute rmware changes. Complete Supply Chain Management Business Needs Analysis Arrowachweber's business needs analysis evaluated customersI materials planning, acquisition, handling, and inventorying processes. Thoroughly understanding its customers' existing capabilities and desired goals enabled Arrowachweber to make practical recommendations that provided sustainable results reected in the bottom line. Custom Computer Products (COP) Arrowyr Schweber's ISO 9002certif1ed Custom Computer Products (CC?) Division was a nationwide source of complete system and subsystem integration, assembly, and testing. Its inhouse support team of engineers and technical personnel provided design and development assistance as well as total project management from concept to completion. The latter originated from a facility certied by Intel for hardware and software design and product integration. Applications support included disk formatting and custom drive congurations; software configuration and customization; custom packaging, painting, and labeling; runin and diagnostic testing; complete functional, diagnostic, environmental, and condence testing; extended warranty; local installation and onsite training; and nationwide field service. Arrowachweber's CCP service reduced production costs and time to market thereby enhancing customers' cash ow. Source: Company records. Exhibit 4 Percent of Arrow Sales with ValuerAdded Content 0.7 - 60% 1975 1990 1985 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1995 Year Source: Company records. Exhibit 5 Consolidated Balance Sheet (dollars in thousands) December 31, 1996 1995 Assets Current assets Cash and short-term investments $ 136,400 $ 93,947 Accounts receivable, less allowance for doubtful accounts 902,878 940,049 ($39,753 in 1996 and $38,670 in 1995) Inventories 1,044,841 1,039, 111 Prepaid expenses and other assets 36 004 31 610 Total current assets 2, 120, 123 2, 104,717 Property, plant and equipment at cost 8,712 14,527 Land Buildings and improvements 77.527 63.857 Machinery and equinment 127 633 112 883 213,602 191,267 Less: accumulated depreciation and amortization 98,377 73,932 115,225 117,335 Investment in affiliated company 34,200 36,031 Cost in excess of net assets of companies acquired, less accumulated 388,787 379, 171 amortization ($57,802 in 1996 and $48,085 in 1995) Other assets 52,016 63,762 $2,710,351 $2,701,016 Liabilities and Shareholders' Equity $ 594,474 $ 561,834 Current liabilities Accounts payable Accrued expenses 180 129 207 738 Short-term borrowings, including current maturities of long-term debt 71,504 117,085 Total current liabilities 846, 107 886,657 I ona-term deht 344 562 451 706 Other liabilities 68.488 68.992 Minority interest 92 712 97 780 Shareholders' equity Common stock, par value $1 Authorized-120.000.000 and 80.000.000 shares in 1996 and 1995 Issued-51, 196,385 and 50,647,826 shares in 1996 and 1995 51, 196 50,648 Capital in excess of par value 549.913 530.324 Retained earnings 805.342 602.633 Foreign currency translation adjustment 8.753 18.398 1 415 204 1 202 003 Less: Treasury stock (1,069,699 and 22,297 shares in 1996 and 1995), at cost 49,065 24 Unamortized employee stock awards 7,657 6,098 Total shareholders' equity 1,358,482 1, 195,881 $2,710,351 $2,701,016 Source: Company recordsExhibit 6 Express Parts Sample Express Parts, Inc. Part Number Requested: SN74LS244N Part Description: LS Octal Buffer/Line Driver Distributor A B C D E F Manufacturer Part Number Qty S Qty S Qty Qty S Qty S Qty Texas Instruments SN74LS244N 62,507 .31 83,200 .28 5,000 .72 30,250 .67 89,660 45 45,000 .62 Motorola SN74LS244N 30,245 .42 77,700 49 89,500 .25 82,300 58 94,200 .26 145,000 .22 Nati Semiconductor DM74LS244N 59,000 30 12,400 .67 64,500 .53 73,000 50 100,000 23 2,200 .70 SGS Thomson T74LS244B1 29,800 55 28,000 .54 73,250 .59 62,900 66 78,780 39 40,245 49 Philips N74LS244N 76,400 .24 25,975 .62 25,000 48 10,000 .70 47,120 58 50,800 55 Click on the price you want Quantity Quote Order Customer: Name: Address: Email Address: Source: Company recordsExhibit 7 Market Segment Mixa Market Segment Optimistic Pessimistic (% and $ of Value-Added Cannibalization of Cannibalization Market Total Business) Businessb BAS" Business BAS Business of BAS Business Segment % I $ % I $ % I $ % I $ % I $ Core CM 20 460 57 262 43 198 30 59 70 139 OEM 56 1,300 72 936 28 364 25 91 60 218 X86 11 250 2 5 98 245 50 122 80 196 ICPd 13 300 80 240 20 60 35 21 80 48 2,310 1,443 867 293 601 Source: Company records. "Calculations assume that value-added business is immune to Internet cannibalization. bincludes scheduled orders and forecast sharing. cBook-and-ship. Industrial computer products

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts