Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Body Text Heading 1 Heading 2 Heading 3 Heading 4 Heading 5 Heading 6 Heading Styles Capital Budgeting West Fraser Timber Co. Ltd West Fraser

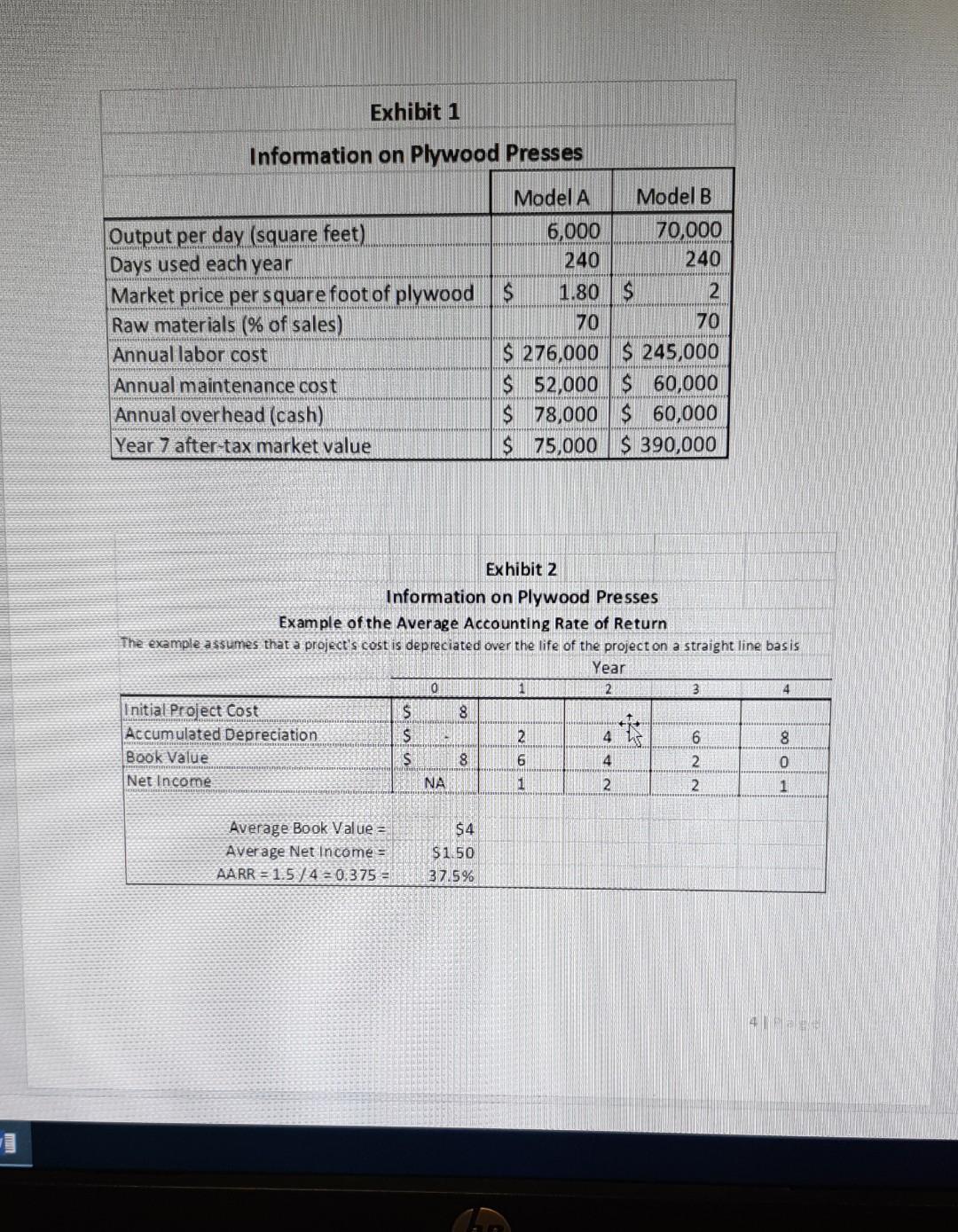

Body Text Heading 1 Heading 2 Heading 3 Heading 4 Heading 5 Heading 6 Heading Styles Capital Budgeting West Fraser Timber Co. Ltd West Fraser is a firm based in Vancouver Island, BC. The company has four plants in British Columbia, and primarily manufactures lumber that is used to produce various types of furniture such as desks and doors. Mary, a recent graduate in Business Administration, wa hired by West Fraser. Mary took the job because she wanted a position with a small firm where she "could make a difference " In fact, during her first meeting with the owner, Mary learned that her first assignment is of some importance and consists of two parts. James Woods, the owner and CEO of West Fraser, wants Mary to (1) perform a financial evaluation on two new machines that he is considering and (2) "critique" the company's capital budgeting policies. PLYWOOD PRESSES The plywood division is an important component of the firm's business and nearly two entire plants are devoted to the production of plywood panels. In brief, the production process involves gluing a thin layer of wood to each side of a particle board that forms the core of the plywood. The plywood is then cut into panels of various sizes suitable for the manufacturing of furniture. The plywood division is operating very close to capacity and James is seriously considering the purchase of an additional plywood press in order to expand the division's production capability. He has narrowed the choice to two models: Model A, which is made in Japan, and the American-manufactured Model B. Model A costs $750,000 and Model B $1,300.000, both figures including installation. Model B has three a dvantages over Model A. First, because it is a bit faster its daily production rate is higher, and James is confident he could sell the extra output. Second, labor costs will be lower since it is easier to operate. Finally, Model B should hold its value better because it is a more state-of-the-art press. Still, Model B is nearly twice as expensive and James isn't sure these advantages are worth the extra cost. 1 Styles Exhibit 1 shows information on each machine. For the purpose of analysis, straight-line depreciation will be used over the seven-year time horizon of the project. The relevant tax rate is 40 percent. The purchase of either machine will cause a modest increase in inventory and receivables. James thinks that these increases will be almost completely offset by changes in accounts payable and accruals. Thus, on balance, working capital requirements for both machines will be negligible and can be ignored in any evaluation. JAMES' FAPG James then explains his capital budgeting practices, which he calls his fixed asset purchase guidelines (FAPG), The first step is to make sure that a proposal fits with the company's mission. James is "simply not interested in projects outside the lumber industry." He is quick to add that nearly all proposals fall within the industry though occasionally one "seems far-out." As an example, James recalls a suggestion that the firm buy a local convenience store. "No way I'd do this. After all, I have enough headaches with the lumber industry. One industry is about all I can handle." For relatively small investments the company relies exclusively on the payback method. There is no set guideline but James admits that he wants to see a two-year payback. And he defines a "small investment" as a project less than $10,000 and "maybe as much as $15.000." Examples include the replacement of relatively inexpensive equipment and the installation of energy-saving devices. James uses somewhat different techniques for more expensive proposals, such as a plant modernization, an expansion, or the purchase of a new plywood press. The payback is still used in part because James uses it as a measure of risk, and in part because it is simple to calculate and easy to understand. He also wants a measure of the project's expected return and based on the suggestion of a friend with a strong accounting background-the firm calculates the investment's average accounting rate of return (AARR). The AARR is determined by dividing the project's average annual net income by its average book value. An example of the AARR is presented in Exhibit 2. In order to be acceptable, a relatively large investment must pass two tests. First, the AARR must exceed the firm's target book return. This book return is currently 20 percent, the figure that James uses to evaluate the performance of the firm's plant managers. 2 VID AGE & ANI Heading 3 Heading 4 Heading 5 Heading 6 Heading Body Text Heading 1 Heading 2 Styles In addition, the project must have an "acceptable payback." James explains, "I use my judgment about what is an 'acceptable' payback. There are no strict guidelines." He admits, though, that he doesn't like to see a project's payback exceed five years. FORECASTING ACCURACY In James's view the most important part of a capital budgeting decision is the accuracy of the forecasts, and he goes to great lengths to make this clear to the firm's executives. He constantly reminds them that "forecasters need to be 'honest seekers of truth' if the company is to be the best it can be. He monitors the company's forecasting efforts in two ways. First, if a project's payback looks "suspiciously low," he personally investigates the forecast. Second, from time to time James has hired outside consultants to compare the actual cash flows of a project with those predicted. And if a set of estimates looks "severely optimistic," then James will question the forecasters, perhaps intensively. As he puts it, "I had better receive satisfactory answers to my questions." Executives who James thinks are negligent or allowing personal bias to cloud their judgment face a severe reprimand and even dismissal in one extreme case. James is aware that many companies are plagued by overly optimistic forecasts, and he is proud of the fact that a post-audit indicated that this has not been true for West Fraser. In fact, there appears to be a tendency for the forecasts to be too conservative. That is, the post-audit showed that on average the predicted cash flows were less than the actual cash flows. REFLECTIONS Back at her apartment that evening Mary reflected on her meeting with James. She sees "both good and not so good" with James's capital budgeting procedures. Perhaps the biggest negative is the lack of any discounted cash flow technique. It is clear to Mary, however, that James recognizes that the 20 percent target return is a book and not a market rate. It also appears that James is willing to consider "capital budgeting techniques based on market returns," as he puts it. Conversations with James suggest that a 15 percent market return would be acceptable. That is Mary thinks that James would undertake a project if he felt that the expected return exceeded 15 percent per year. Mary is pleased at the responsibility of the assignment and is eager to make a difference." At the same time, however, she is a bit apprehensive Mary realizes that James will take her report very seriously, and knows that her recommendations must not only be correct, but must also be clearly justified and explained 3 Exhibit 1 Information on Plywood Presses Model A Model B Output per day (square feet) 6,000 70,000 Days used each year 240 240 Market price per square foot of plywood $ 1.80 $ 2 Raw materials (% of sales) 70 70 Annual labor cost $ 276,000 $ 245,000 Annual maintenance cost $ 52,000 $ 60,000 Annual overhead (cash) $ 78,000 $60,000 Year 7 after-tax market value $ 75,000 $ 390,000 Exhibit 2 Information on Plywood Presses Example of the Average Accounting Rate of Return The example assumes that a project's cost is depreciated over the life of the project on a straight line basis Year 0 1 2 3 4 Initial Project Cost $ 8 Accumulated Depreciation S 2 4 6 8 Book Value S 8 6 4 2 Net Income NA 1 2 2 1 ** 000 Average Book Value = Average Net Income - AARR = 1.5 / 4 = 0.375 54 $1.50 37.5% 4 Required Read the case of West Fraser Timber-Capital Budgeting Procedures Create a report that includes the following: 1. A summary and evaluation of West Fraser Timber's current capital budgeting procedures and method for estimating cash flows. 2. Calculate Model A and Model B Press's Free Cash Flow (FCF) per year. 3. Provide an explanation and calculation of the following capital budgeting methods (include the accept/reject criteria): a. Payback period b. IRR C. NPV d. Profitability index 4. Suggest a capital budgeting method West Fraser Timber can use to improve its capital budgeting procedure. Explain why you chose one capital budgeting method over another. I 5. Based on the calculations from required 4, provide a recommendation of which if any of the two presses West Fraser Timber should purchase. Explain your recommendation using your calculations and rankings from required 3. Body Text Heading 1 Heading 2 Heading 3 Heading 4 Heading 5 Heading 6 Heading Styles Capital Budgeting West Fraser Timber Co. Ltd West Fraser is a firm based in Vancouver Island, BC. The company has four plants in British Columbia, and primarily manufactures lumber that is used to produce various types of furniture such as desks and doors. Mary, a recent graduate in Business Administration, wa hired by West Fraser. Mary took the job because she wanted a position with a small firm where she "could make a difference " In fact, during her first meeting with the owner, Mary learned that her first assignment is of some importance and consists of two parts. James Woods, the owner and CEO of West Fraser, wants Mary to (1) perform a financial evaluation on two new machines that he is considering and (2) "critique" the company's capital budgeting policies. PLYWOOD PRESSES The plywood division is an important component of the firm's business and nearly two entire plants are devoted to the production of plywood panels. In brief, the production process involves gluing a thin layer of wood to each side of a particle board that forms the core of the plywood. The plywood is then cut into panels of various sizes suitable for the manufacturing of furniture. The plywood division is operating very close to capacity and James is seriously considering the purchase of an additional plywood press in order to expand the division's production capability. He has narrowed the choice to two models: Model A, which is made in Japan, and the American-manufactured Model B. Model A costs $750,000 and Model B $1,300.000, both figures including installation. Model B has three a dvantages over Model A. First, because it is a bit faster its daily production rate is higher, and James is confident he could sell the extra output. Second, labor costs will be lower since it is easier to operate. Finally, Model B should hold its value better because it is a more state-of-the-art press. Still, Model B is nearly twice as expensive and James isn't sure these advantages are worth the extra cost. 1 Styles Exhibit 1 shows information on each machine. For the purpose of analysis, straight-line depreciation will be used over the seven-year time horizon of the project. The relevant tax rate is 40 percent. The purchase of either machine will cause a modest increase in inventory and receivables. James thinks that these increases will be almost completely offset by changes in accounts payable and accruals. Thus, on balance, working capital requirements for both machines will be negligible and can be ignored in any evaluation. JAMES' FAPG James then explains his capital budgeting practices, which he calls his fixed asset purchase guidelines (FAPG), The first step is to make sure that a proposal fits with the company's mission. James is "simply not interested in projects outside the lumber industry." He is quick to add that nearly all proposals fall within the industry though occasionally one "seems far-out." As an example, James recalls a suggestion that the firm buy a local convenience store. "No way I'd do this. After all, I have enough headaches with the lumber industry. One industry is about all I can handle." For relatively small investments the company relies exclusively on the payback method. There is no set guideline but James admits that he wants to see a two-year payback. And he defines a "small investment" as a project less than $10,000 and "maybe as much as $15.000." Examples include the replacement of relatively inexpensive equipment and the installation of energy-saving devices. James uses somewhat different techniques for more expensive proposals, such as a plant modernization, an expansion, or the purchase of a new plywood press. The payback is still used in part because James uses it as a measure of risk, and in part because it is simple to calculate and easy to understand. He also wants a measure of the project's expected return and based on the suggestion of a friend with a strong accounting background-the firm calculates the investment's average accounting rate of return (AARR). The AARR is determined by dividing the project's average annual net income by its average book value. An example of the AARR is presented in Exhibit 2. In order to be acceptable, a relatively large investment must pass two tests. First, the AARR must exceed the firm's target book return. This book return is currently 20 percent, the figure that James uses to evaluate the performance of the firm's plant managers. 2 VID AGE & ANI Heading 3 Heading 4 Heading 5 Heading 6 Heading Body Text Heading 1 Heading 2 Styles In addition, the project must have an "acceptable payback." James explains, "I use my judgment about what is an 'acceptable' payback. There are no strict guidelines." He admits, though, that he doesn't like to see a project's payback exceed five years. FORECASTING ACCURACY In James's view the most important part of a capital budgeting decision is the accuracy of the forecasts, and he goes to great lengths to make this clear to the firm's executives. He constantly reminds them that "forecasters need to be 'honest seekers of truth' if the company is to be the best it can be. He monitors the company's forecasting efforts in two ways. First, if a project's payback looks "suspiciously low," he personally investigates the forecast. Second, from time to time James has hired outside consultants to compare the actual cash flows of a project with those predicted. And if a set of estimates looks "severely optimistic," then James will question the forecasters, perhaps intensively. As he puts it, "I had better receive satisfactory answers to my questions." Executives who James thinks are negligent or allowing personal bias to cloud their judgment face a severe reprimand and even dismissal in one extreme case. James is aware that many companies are plagued by overly optimistic forecasts, and he is proud of the fact that a post-audit indicated that this has not been true for West Fraser. In fact, there appears to be a tendency for the forecasts to be too conservative. That is, the post-audit showed that on average the predicted cash flows were less than the actual cash flows. REFLECTIONS Back at her apartment that evening Mary reflected on her meeting with James. She sees "both good and not so good" with James's capital budgeting procedures. Perhaps the biggest negative is the lack of any discounted cash flow technique. It is clear to Mary, however, that James recognizes that the 20 percent target return is a book and not a market rate. It also appears that James is willing to consider "capital budgeting techniques based on market returns," as he puts it. Conversations with James suggest that a 15 percent market return would be acceptable. That is Mary thinks that James would undertake a project if he felt that the expected return exceeded 15 percent per year. Mary is pleased at the responsibility of the assignment and is eager to make a difference." At the same time, however, she is a bit apprehensive Mary realizes that James will take her report very seriously, and knows that her recommendations must not only be correct, but must also be clearly justified and explained 3 Exhibit 1 Information on Plywood Presses Model A Model B Output per day (square feet) 6,000 70,000 Days used each year 240 240 Market price per square foot of plywood $ 1.80 $ 2 Raw materials (% of sales) 70 70 Annual labor cost $ 276,000 $ 245,000 Annual maintenance cost $ 52,000 $ 60,000 Annual overhead (cash) $ 78,000 $60,000 Year 7 after-tax market value $ 75,000 $ 390,000 Exhibit 2 Information on Plywood Presses Example of the Average Accounting Rate of Return The example assumes that a project's cost is depreciated over the life of the project on a straight line basis Year 0 1 2 3 4 Initial Project Cost $ 8 Accumulated Depreciation S 2 4 6 8 Book Value S 8 6 4 2 Net Income NA 1 2 2 1 ** 000 Average Book Value = Average Net Income - AARR = 1.5 / 4 = 0.375 54 $1.50 37.5% 4 Required Read the case of West Fraser Timber-Capital Budgeting Procedures Create a report that includes the following: 1. A summary and evaluation of West Fraser Timber's current capital budgeting procedures and method for estimating cash flows. 2. Calculate Model A and Model B Press's Free Cash Flow (FCF) per year. 3. Provide an explanation and calculation of the following capital budgeting methods (include the accept/reject criteria): a. Payback period b. IRR C. NPV d. Profitability index 4. Suggest a capital budgeting method West Fraser Timber can use to improve its capital budgeting procedure. Explain why you chose one capital budgeting method over another. I 5. Based on the calculations from required 4, provide a recommendation of which if any of the two presses West Fraser Timber should purchase. Explain your recommendation using your calculations and rankings from required 3

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started