Question: brief communications 1. Aizenberg, J., Tkachenko, A., Weiner, S., Addadi, L. & Hendler, G. Nature 412, 819-822 (2001). 2. McPhedran, R. C. et al. Aust.

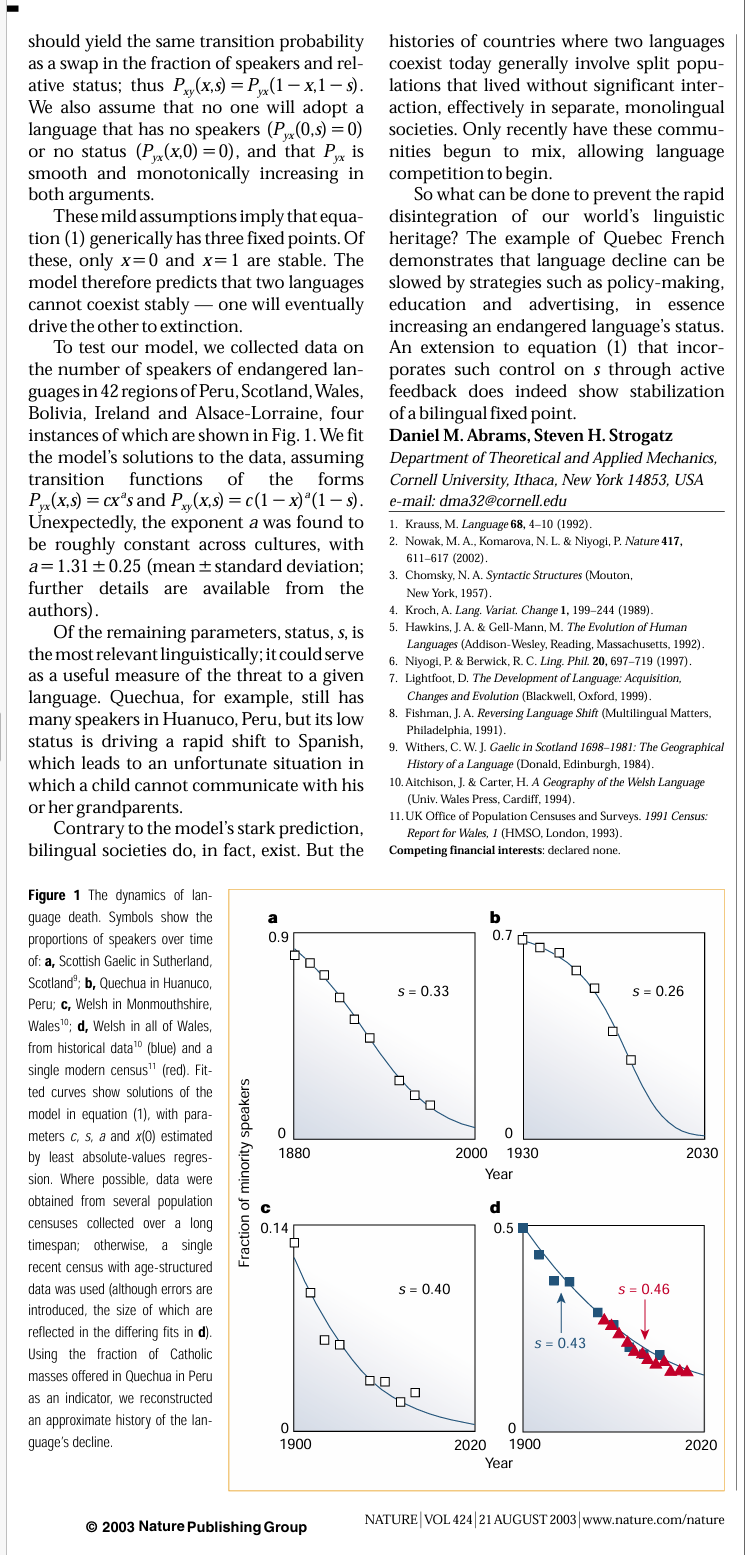

brief communications 1. Aizenberg, J., Tkachenko, A., Weiner, S., Addadi, L. & Hendler, G. Nature 412, 819-822 (2001). 2. McPhedran, R. C. et al. Aust. J. Chem. 54, 241-244 (2001). 3. Cattaneo-Vietti, R. et al. Nature 383, 397-398 (1996). 4. Perry, C. C. & Keeling-Tucker, T. J. Blol. Inorg. Chem. 5, 537-550 (2000). 5. Simpson, T. L. The Cell Biology of Sponges (Springer, New York, 1984 ) . 6. Sarikaya, M. et al. J. Mater. Res. 16, 1420-1428 (2001). 7. Marcuse, D. Principles of Optical Fiber Measurements (Academic, New York, 1981). 8. Clegg. W. J., Kendall, K., Alford, N. M., Button, T. W. & Birchall, J. D. Nature 347, 455-457 (1990). 9. Kamat, S., Su, X., Ballarini, R. & Heuer, A. H. Nature 405, 1036-1040 (2000). 10. Cha, J. N., Stucky, G. D., Morse, D. E. & Deming, T. J. Nature 403, 289-292 (2000). 1 1. Kroger, N., Lorenz, S., Brunner, E. & Sumper, M. Science 298, 584-586 (2002). Competing financial interests: declared none. Linguistics Modelling the dynamics of language death thousands of the world's languages are vanishing at an alarming rate, with 90% of them being expected to disap- pear with the current generation . Here we develop a simple model of language compe- tition that explains historical data on the decline of Welsh, Scottish Gaelic, Quechua (the most common surviving indigenous language in the Americas) and other endan- gered languages. A linguistic parameter that quantifies the threat of language extinction can be derived from the model and may be useful in the design and evaluation of language-preservation programmes. Previous models of language dynamics have focused on the transmission and evolu- tion of syntax, grammar or other structural properties of a language itself-. In contrast, the model we describe here idealizes lan- guages as fixed, and as competing with each other for speakers. For simplicity, we also assume a highly connected population, with no spatial or social structure, in which all speakers are monolingual. Consider a system of two competing lan- guages, Xand Y, in which the attractiveness of a language increases with both its number of speakers and its perceived status (a parame- ter that reflects the social or economic opportunities afforded to its speakers) . Sup- pose an individual converts from Y to X with a probability, per unit of time, of Pyx(x,s), where x is the fraction of the population speaking X, and 0s1 is a measure of X's relative status. A minimal model for lan- guage change is therefore dx dt = yPyx(x,s) - XP xy (X,5) (1) where y=1 - x is the complementary frac- tion of the population speaking Y at time t. By symmetry, interchanging languages 900should yield the same transition probability histories of countries where two languages as a swap in the fraction of speakers and rel- coexist today generally involve split popu- ative status; thus Pry(x,s) = Pyx(1 - x,1 -s). lations that lived without significant inter- We also assume that no one will adopt a action, effectively in separate, monolingual language that has no speakers (Pyx(0,s) =0) societies. Only recently have these commu- or no status (Pyx(x,0) =0), and that P,, is nities begun to mix, allowing language smooth and monotonically increasing in competition to begin. both arguments. So what can be done to prevent the rapid These mild assumptions imply that equa- disintegration of our world's linguistic tion (1) generically has three fixed points. Of heritage? The example of Quebec French these, only x=0 and x= 1 are stable. The demonstrates that language decline can be model therefore predicts that two languages slowed by strategies such as policy-making, cannot coexist stably - one will eventually education and advertising, in essence drive the other to extinction. increasing an endangered language's status. To test our model, we collected data on An extension to equation (1) that incor- the number of speakers of endangered lan- porates such control on s through active guages in 42 regions of Peru, Scotland, Wales, feedback does indeed show stabilization Bolivia, Ireland and Alsace-Lorraine, four of a bilingual fixed point. instances of which are shown in Fig. 1. We fit Daniel M. Abrams, Steven H. Strogatz the model's solutions to the data, assuming Department of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics, transition functions of the forms Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853, USA Pyx(x,s) = cx's and Pry(x,s) = c(1 -x)(1-s). e-mail: dma32@cornell.edu Unexpectedly, the exponent a was found to 1. Krauss, M. Language 68, 4-10 (1992). be roughly constant across cultures, with 2. Nowak, M. A., Komarova, N. L. & Niyogi, P. Nature 417, a=1.31 +0.25 (mean + standard deviation; 611-617 (2002). 3. Chomsky, N. A. Syntactic Structures (Mouton, further details are available from the New York, 1957). authors) . 4. Kroch, A. Lang. Variat. Change 1, 199-244 (1989). Of the remaining parameters, status, s, is 5. Hawkins, J. A. & Gell-Mann, M. The Evolution of Human the most relevant linguistically; it could serve Languages (Addison-Wesley, Reading, Massachusetts, 1992). 6. Niyogi, P. & Berwick, R. C. Ling. Phil. 20, 697-719 (1997). as a useful measure of the threat to a given 7. Lightfoot, D. The Development of Language: Acquisition, language. Quechua, for example, still has Changes and Evolution (Blackwell, Oxford, 1999). many speakers in Huanuco, Peru, but its low B. Fishman, J. A. Reversing Language Shift (Multilingual Matters, Philadelphia, 1991). status is driving a rapid shift to Spanish, 9. Withers, C. W. J. Gaelic in Scotland 1698-1981: The Geographical which leads to an unfortunate situation in History of a Language (Donald, Edinburgh, 1984). which a child cannot communicate with his 10. Aitchison, J. & Carter, H. A Geography of the Welsh Language or her grandparents. (Univ. Wales Press, Cardiff, 1994). 11. UK Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. 1991 Census: Contrary to the model's stark prediction, Report for Wales, I (HMSO, London, 1993). bilingual societies do, in fact, exist. But the Competing financial interests: declared none. Figure 1 The dynamics of lan- guage death. Symbols show the a b proportions of speakers over time 0.9 0.75 of: a, Scottish Gaelic in Sutherland, Scotland ; b, Quechua in Huanuco, S = 0.33 S = 0.26 Peru; c, Welsh in Monmouthshire, Wales"; d, Welsh in all of Wales, from historical data" (blue) and a single modern census" (red). Fit- ted curves show solutions of the model in equation (1), with para- meters c, s, a and x(0) estimated 0 by least absolute-values regres- 1880 2000 2030 Fraction of minority speakers sion. Where possible, data were Year obtained from several population C d censuses collected over a long 0.14 0.5 timespan; otherwise, a single recent census with age-structured data was used (although errors are 0 S = 0.40 S = 0.46 introduced, the size of which are reflected in the differing fits in d). S = 0.43 Using the fraction of Catholic masses offered in Quechua in Peru as an indicator, we reconstructed 0 an approximate history of the lan- 0 0 guage's decline. 1900 2020 1900 2020 Year 2003 Nature Publishing Group NATURE VOL 424 21 AUGUST 2003 www.nature.comature

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts