Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Case 16 Please be as elaborate as possible, this is a Strategic Management university paper. The conclusion is the basic question. Identify the problems and

Case 16

Please be as elaborate as possible, this is a Strategic Management university paper.

The conclusion is the basic question. Identify the problems and give solutions. Give a complete SWOT and PESTEL analysis of the Case study (SWOT and PESTEL).

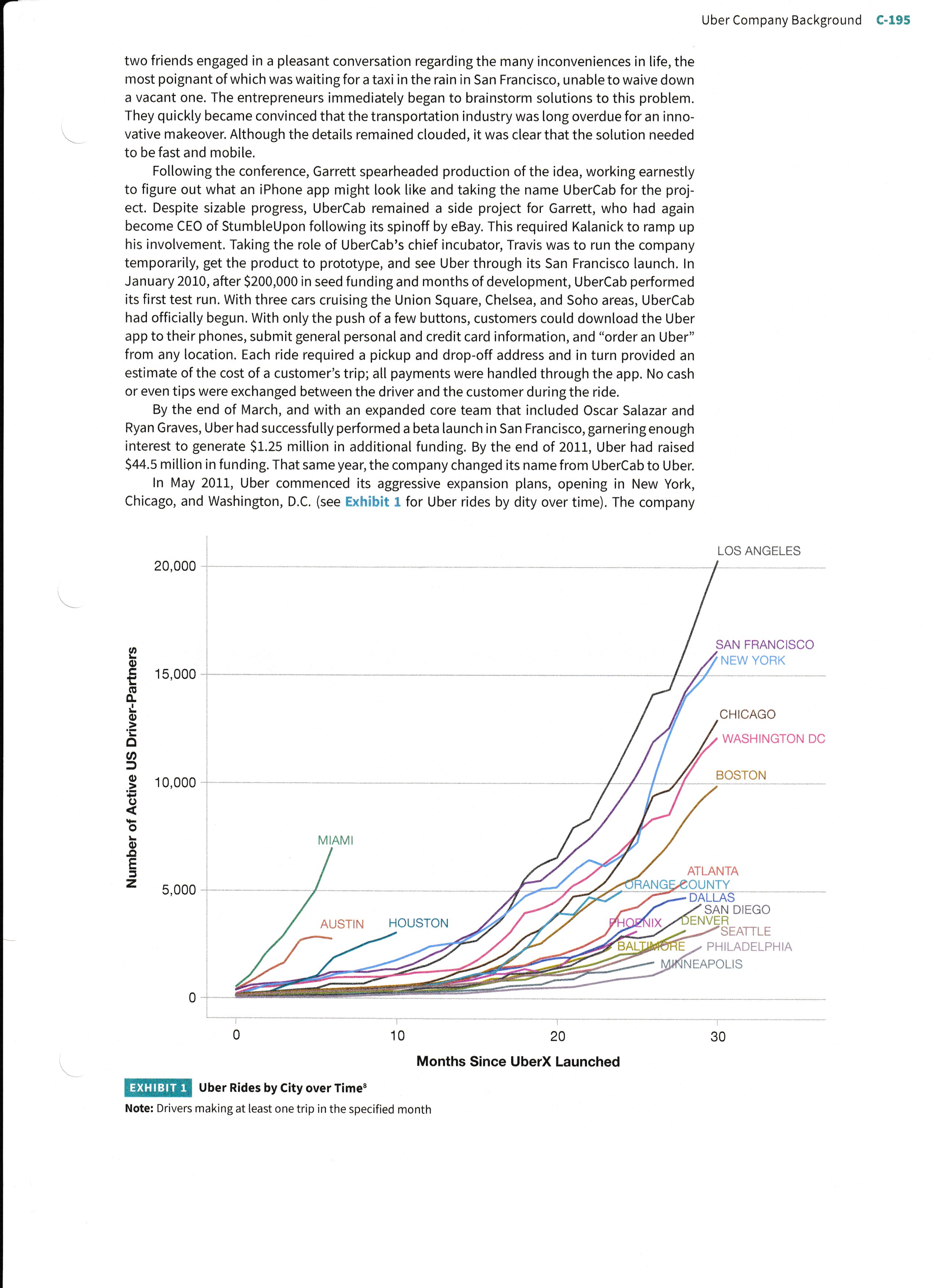

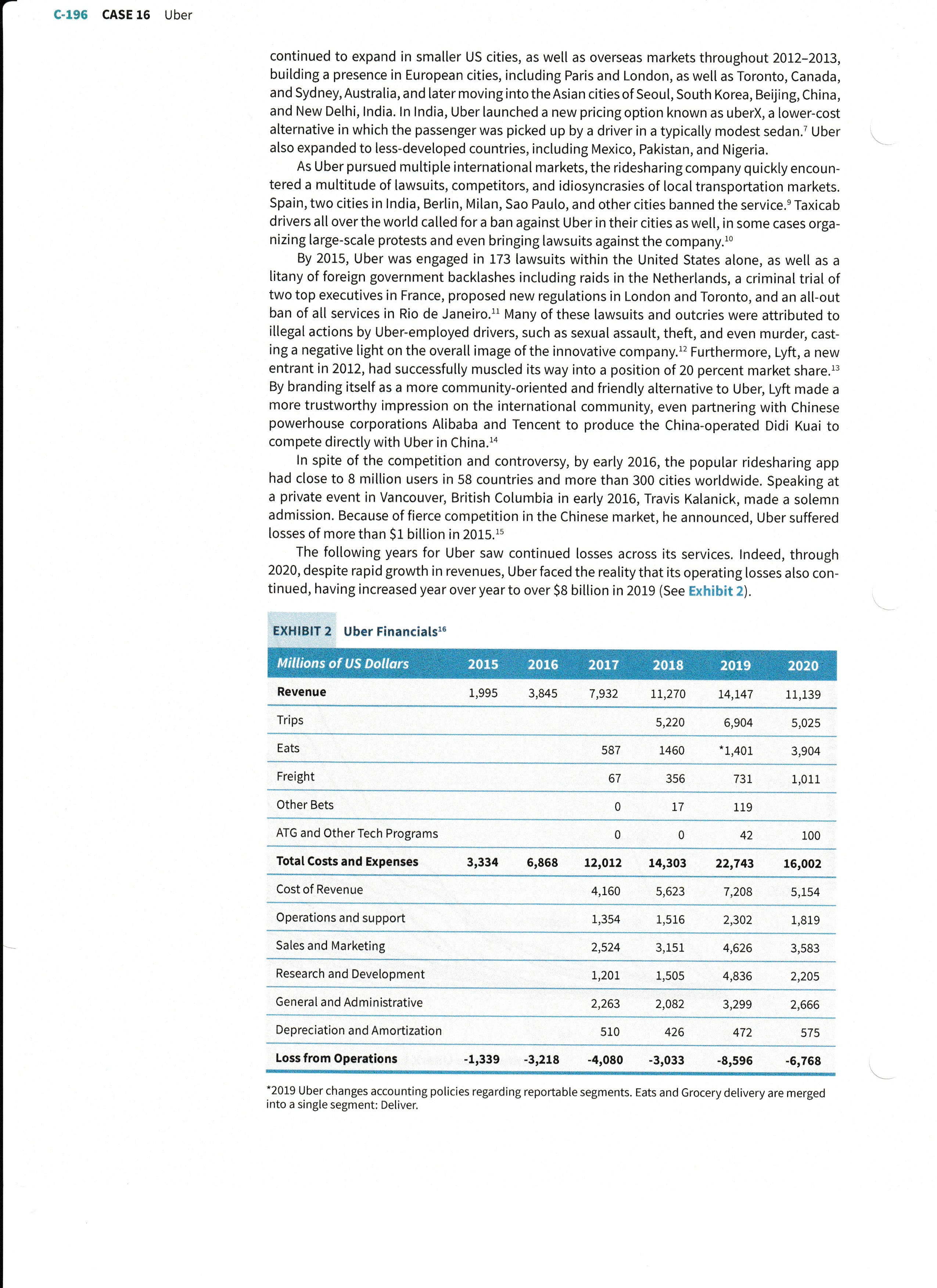

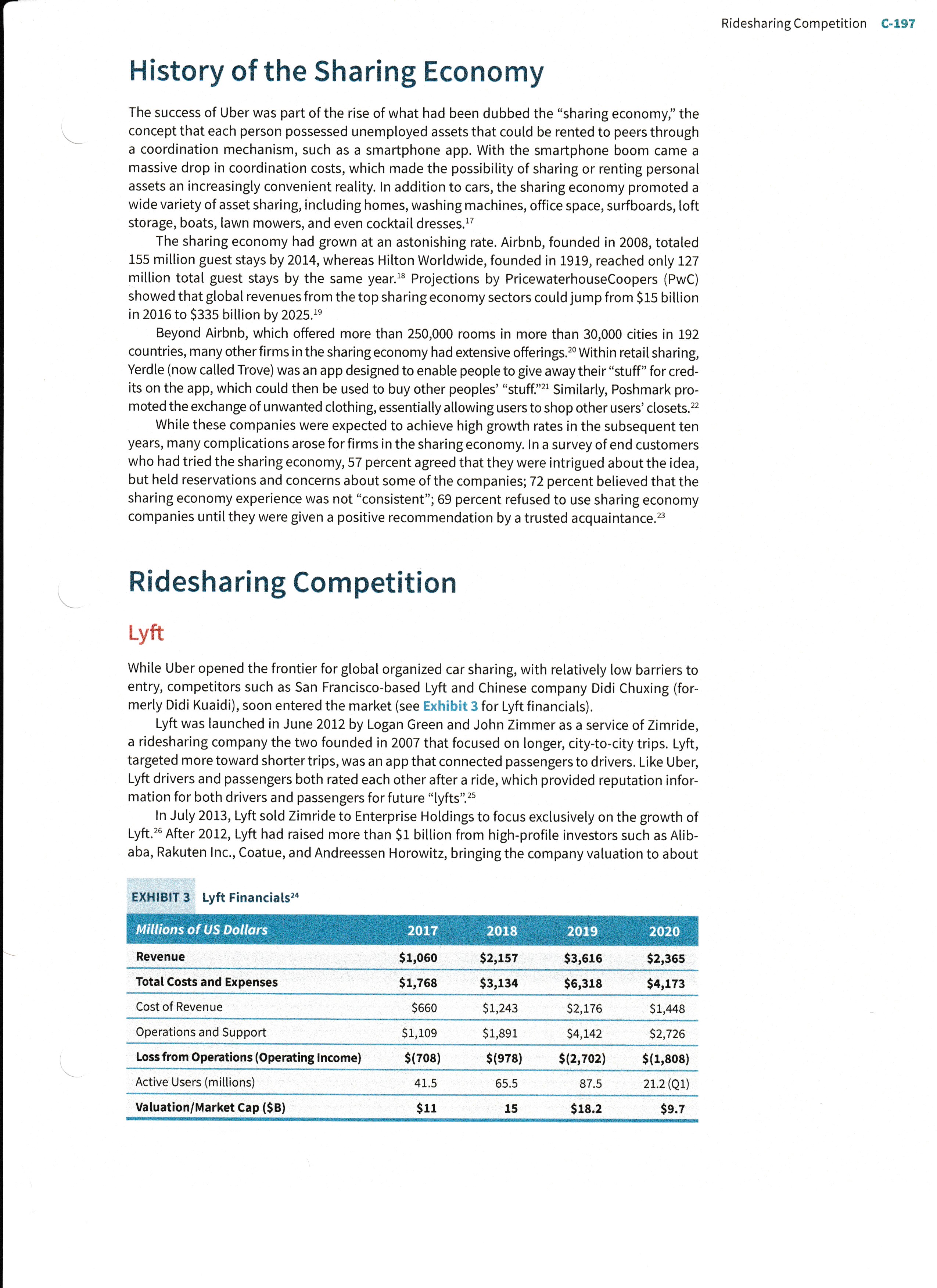

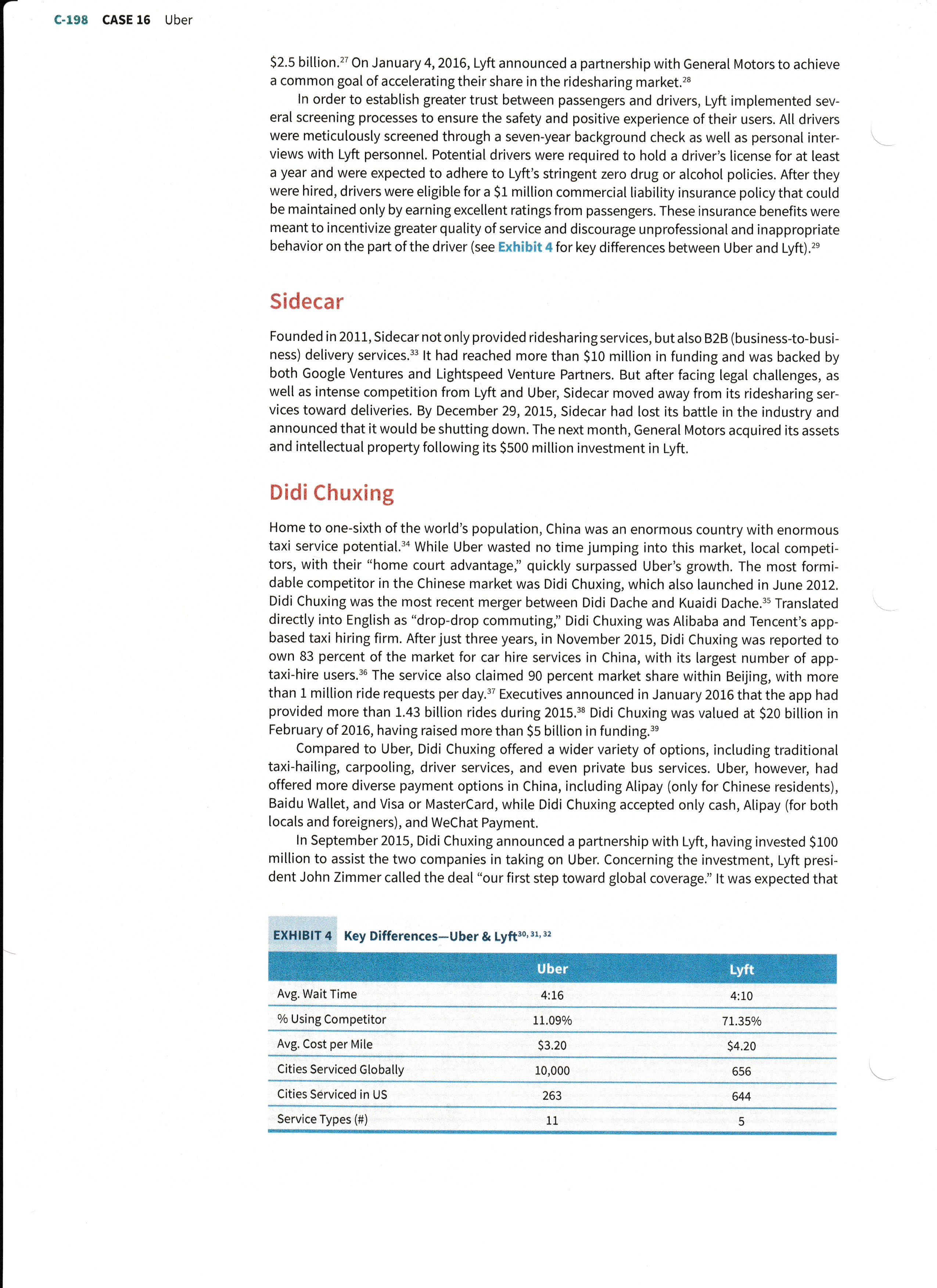

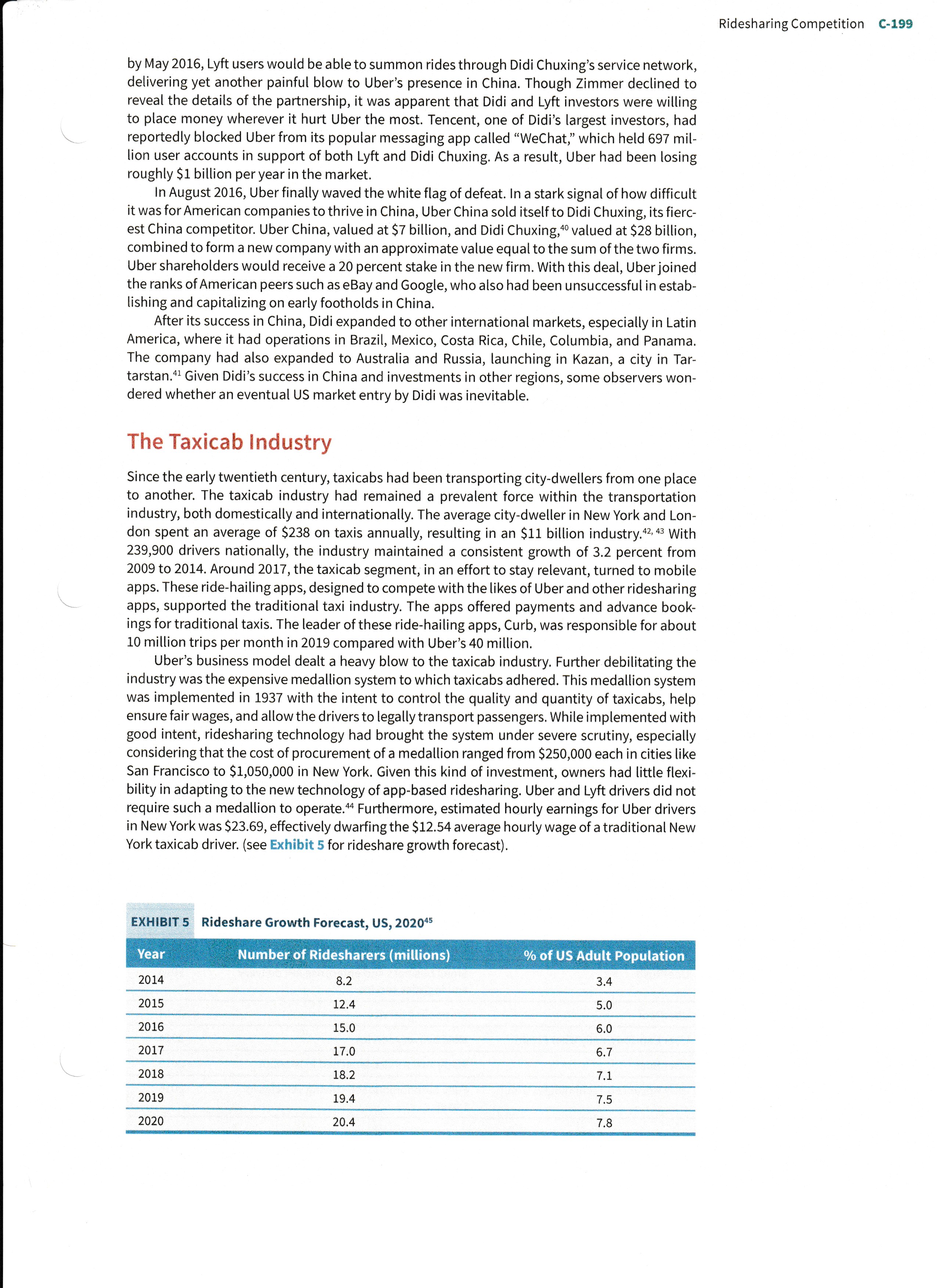

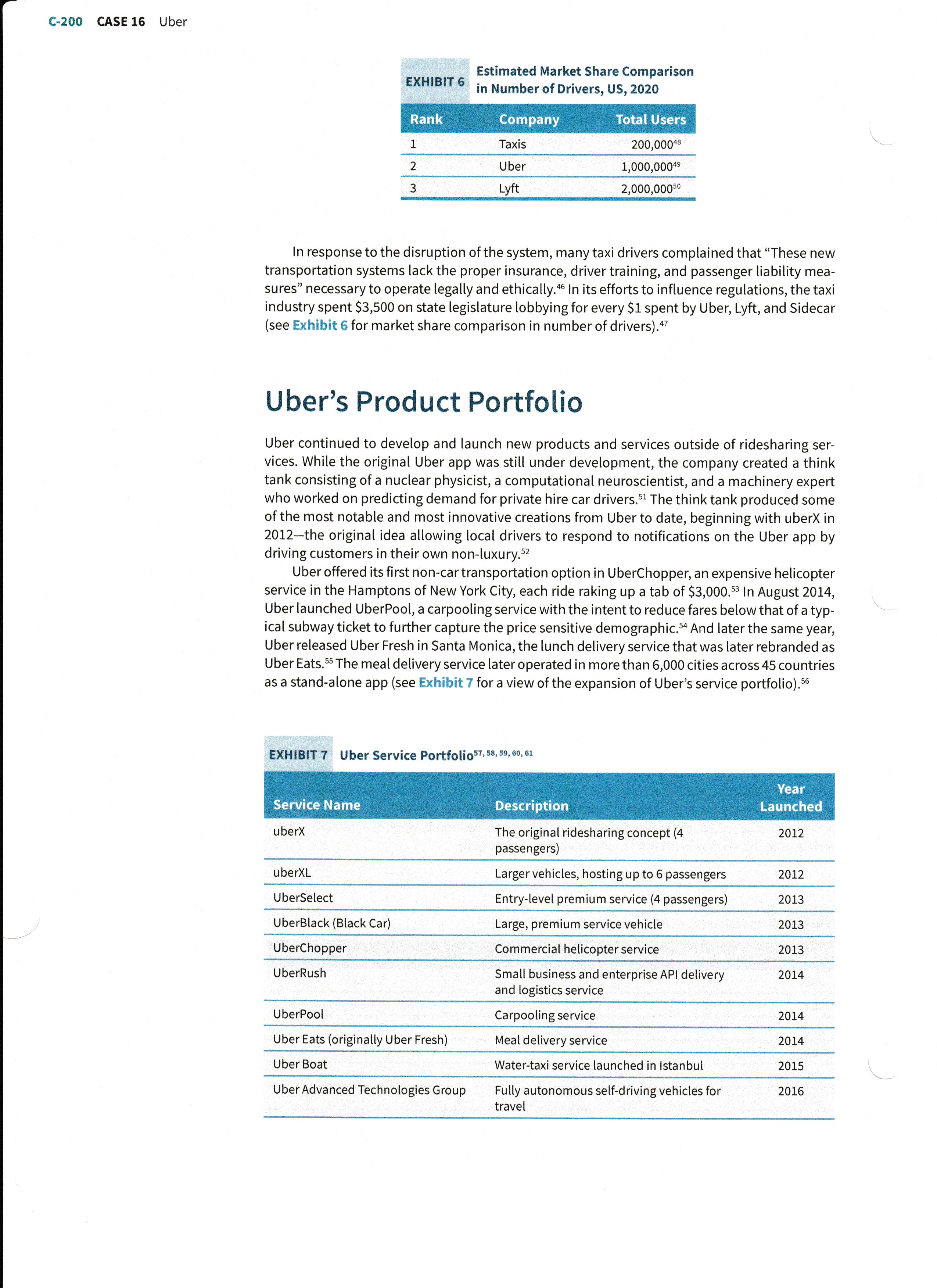

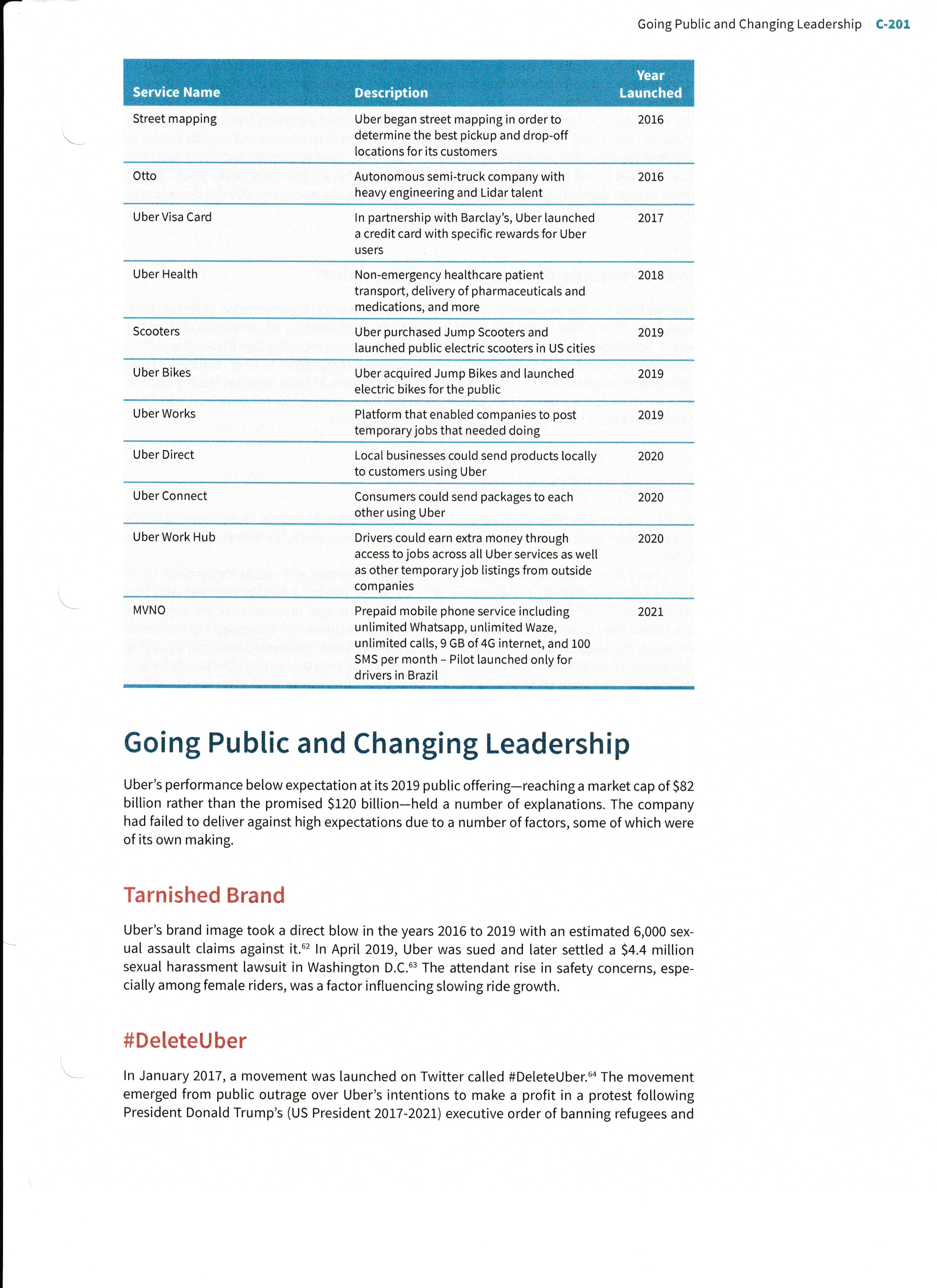

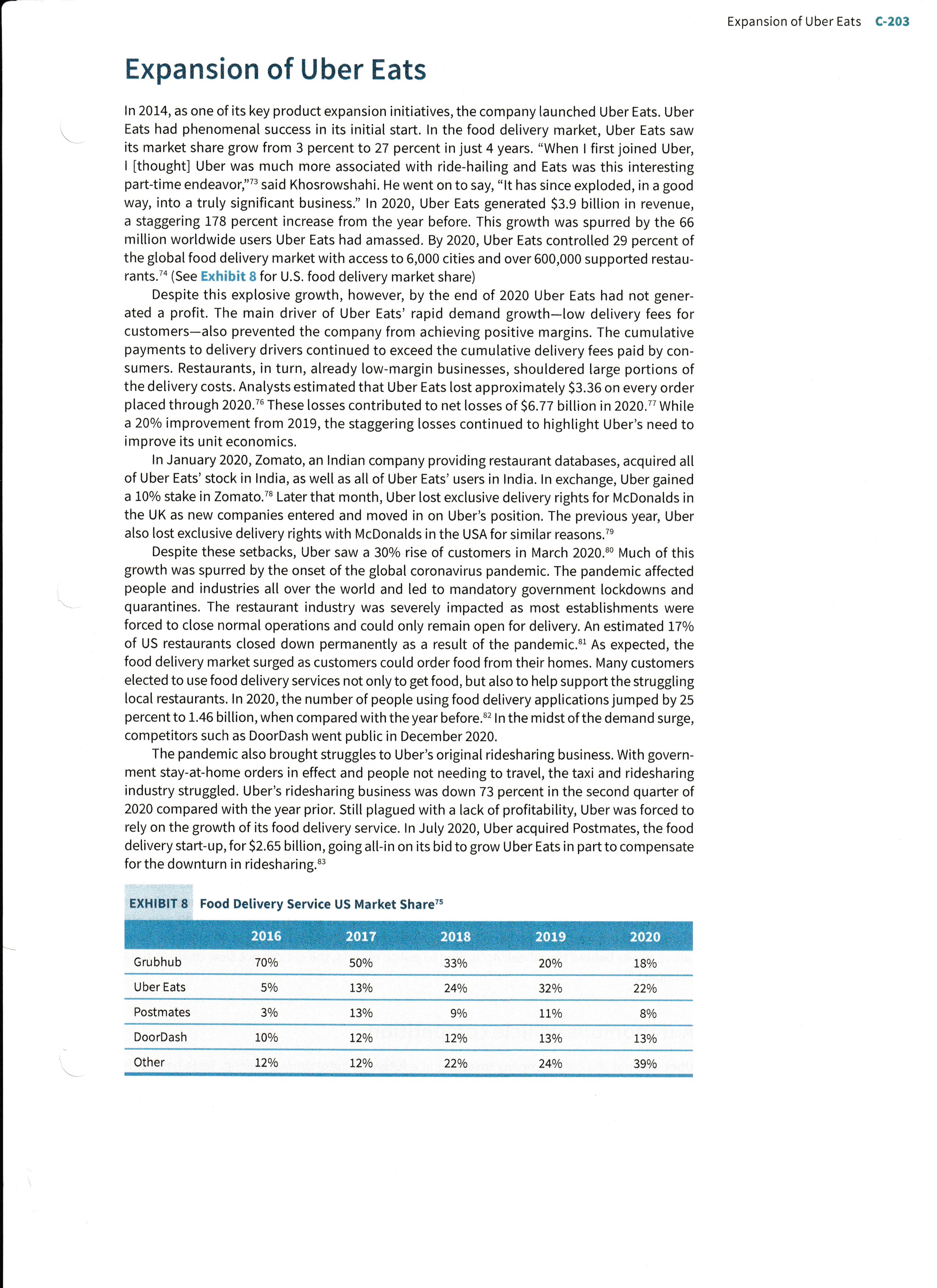

Uber, a company providing peer-to-peer shared car rides through a smartphone app, went public at a valuation of $82 billion in May of 2019 , raising $8.1 billion at $45 per share. 1 Prior to this, Uber had announced that it expected to reach a market value of $120 billion at its initial public offering (IPO), which created a frenzy in Silicon Valley and on Wall Street, as Uber would become the biggest American company to initially list on an American stock exchange-larger even than Facebook, which went public in 2012 at an impressive \$104 billion valuation. 2 However, Uber was not able to capitalize on the $120 billion promise and never reached a market cap greater than $82 billion that year. Uber would not exceed its IPO market cap until November of 2020 during a historic run up of the stock market. 3 Dara Khosrowshahi, who had become CEO in 2017, had already faced numerous challenges as he moved the company toward its IPO. Challenges included charges that the culture was rife with sexism, that drivers were involved in hundreds of sexual assaults and other crimes on passengers, and that the company still had not turned a profit. Hired to "clean up the mess" left by former CEO Travis Kalanick, Mr. Khosrowshahi had quietly listened to employees and steadied the ship. 4 Yet, while negative headlines finally began to subside, operating losses continued to expand unabated. That problem was made worse in March 2020 as the global coronavirus pandemic cut demand for rides. Serendipitously, as demand for rides fell, a silver lining emerged in the form of rapidly expanding demand for Uber Eats, the food delivery service owned by the company. The stark ability of one growth business in the portfolio to make up for some of the downturn in another business proved crucial during the pandemic. But Mr. Khosrowshahi also knew that the core business of ridesharing continued to face numerous challenges of regulation, lawsuits, competition, and operating losses. This presented an ongoing need to either find a profitability fix for the core business or to find new businesses that could potentially supersede or replace ridesharing. Beyond food delivery in Uber Eats, another obvious place to look was to autonomous vehicles, which were seen to have the potential to replace drivers with a fleet of robotaxis. Uber had been investing heavily in this area, and yet success in a future vision of autonomous vehicle-based transportation was anything but assured. Other competitors were also investing heavily in the space and no company had yet reached the goal of 100 percent autonomy with its vehicles. As Uber emerged from the worst effects of the pandemic, Mr. Khosrowshahi faced a number of challenges. Could he make the rideshare business profitable and if so, how? Should he continue investing in autonomous vehicles and if so, where? Should he launch new businesses? And crucially, how could he configure and coordinate Uber's portfolio of businesses so as to achieve overall corporate growth and profitability? Uber Company Background While attending the LeWeb conference in Paris, France, old-time friends Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp stumbled upon the idea for Uber. 5 Travis had recently sold his company Red Swoosh to Takamai Technologies for $19 million, and Garrett had sold his company StumbleUpon to eBay for $75 million and was doing "hard time" at a big company. 6 During the conference, these two friends engaged in a pleasant conversation regarding the many inconveniences in life, the most poignant of which was waiting for a taxi in the rain in San Francisco, unable to waive down a vacant one. The entrepreneurs immediately began to brainstorm solutions to this problem. They quickly became convinced that the transportation industry was long overdue for an innovative makeover. Although the details remained clouded, it was clear that the solution needed to be fast and mobile. Following the conference, Garrett spearheaded production of the idea, working earnestly to figure out what an iPhone app might look like and taking the name UberCab for the project. Despite sizable progress, UberCab remained a side project for Garrett, who had again become CEO of StumbleUpon following its spinoff by eBay. This required Kalanick to ramp up his involvement. Taking the role of UberCab's chief incubator, Travis was to run the company temporarily, get the product to prototype, and see Uber through its San Francisco launch. In January 2010 , after $200,000 in seed funding and months of development, UberCab performed its first test run. With three cars cruising the Union Square, Chelsea, and Soho areas, UberCab had officially begun. With only the push of a few buttons, customers could download the Uber app to their phones, submit general personal and credit card information, and "order an Uber" from any location. Each ride required a pickup and drop-off address and in turn provided an estimate of the cost of a customer's trip; all payments were handled through the app. No cash or even tips were exchanged between the driver and the customer during the ride. By the end of March, and with an expanded core team that included Oscar Salazar and Ryan Graves, Uber had successfully performed a beta launch in San Francisco, garnering enough interest to generate $1.25 million in additional funding. By the end of 2011, Uber had raised $44.5 million in funding. That same year, the company changed its name from UberCab to Uber. In May 2011, Uber commenced its aggressive expansion plans, opening in New York, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. (see Exhibit 1 for Uber rides by dity over time). The company EXHIBIT 1 Uber Rides by City over Time 8 Note: Drivers making at least one trip in the specified month continued to expand in smaller US cities, as well as overseas markets throughout 2012-2013, building a presence in European cities, including Paris and London, as well as Toronto, Canada, and Sydney, Australia, and later moving into the Asian cities of Seoul, South Korea, Beijing, China, and New Delhi, India. In India, Uber launched a new pricing option known as uberX, a lower-cost alternative in which the passenger was picked up by a driver in a typically modest sedan. 7 Uber also expanded to less-developed countries, including Mexico, Pakistan, and Nigeria. As Uber pursued multiple international markets, the ridesharing company quickly encountered a multitude of lawsuits, competitors, and idiosyncrasies of local transportation markets. Spain, two cities in India, Berlin, Milan, Sao Paulo, and other cities banned the service. 9 Taxicab drivers all over the world called for a ban against Uber in their cities as well, in some cases organizing large-scale protests and even bringing lawsuits against the company. 10 By 2015, Uber was engaged in 173 lawsuits within the United States alone, as well as a litany of foreign government backlashes including raids in the Netherlands, a criminal trial of two top executives in France, proposed new regulations in London and Toronto, and an all-out ban of all services in Rio de Janeiro. 11 Many of these lawsuits and outcries were attributed to illegal actions by Uber-employed drivers, such as sexual assault, theft, and even murder, casting a negative light on the overall image of the innovative company. 12 Furthermore, Lyft, a new entrant in 2012, had successfully muscled its way into a position of 20 percent market share. 13 By branding itself as a more community-oriented and friendly alternative to Uber, Lyft made a more trustworthy impression on the international community, even partnering with Chinese powerhouse corporations Alibaba and Tencent to produce the China-operated Didi Kuai to compete directly with Uber in China. 14 In spite of the competition and controversy, by early 2016, the popular ridesharing app had close to 8 million users in 58 countries and more than 300 cities worldwide. Speaking at a private event in Vancouver, British Columbia in early 2016, Travis Kalanick, made a solemn admission. Because of fierce competition in the Chinese market, he announced, Uber suffered losses of more than $1 billion in 2015. 15 The following years for Uber saw continued losses across its services. Indeed, through 2020 , despite rapid growth in revenues, Uber faced the reality that its operating losses also continued, having increased year over year to over $8 billion in 2019 (See Exhibit 2). EXHIBIT? Ihar Financials 16 *2019 Uber changes accounting policies regarding reportable segments. Eats and Grocery delivery are merged into a single segment: Deliver. History of the Sharing Economy The success of Uber was part of the rise of what had been dubbed the "sharing economy," the concept that each person possessed unemployed assets that could be rented to peers through a coordination mechanism, such as a smartphone app. With the smartphone boom came a massive drop in coordination costs, which made the possibility of sharing or renting personal assets an increasingly convenient reality. In addition to cars, the sharing economy promoted a wide variety of asset sharing, including homes, washing machines, office space, surfboards, loft storage, boats, lawn mowers, and even cocktail dresses. 17 The sharing economy had grown at an astonishing rate. Airbnb, founded in 2008, totaled 155 million guest stays by 2014, whereas Hilton Worldwide, founded in 1919, reached only 127 million total guest stays by the same year. 18 Projections by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC) showed that global revenues from the top sharing economy sectors could jump from $15 billion in 2016 to $335 billion by 2025.19 Beyond Airbnb, which offered more than 250,000 rooms in more than 30,000 cities in 192 countries, many other firms in the sharing economy had extensive offerings. 20 Within retail sharing, Yerdle (now called Trove) was an app designed to enable people to give away their "stuff" for credits on the app, which could then be used to buy other peoples' "stuff."21 Similarly, Poshmark promoted the exchange of unwanted clothing, essentially allowing users to shop other users' closets. 22 While these companies were expected to achieve high growth rates in the subsequent ten years, many complications arose for firms in the sharing economy. In a survey of end customers who had tried the sharing economy, 57 percent agreed that they were intrigued about the idea, but held reservations and concerns about some of the companies; 72 percent believed that the sharing economy experience was not "consistent"; 69 percent refused to use sharing economy companies until they were given a positive recommendation by a trusted acquaintance. 23 Ridesharing Competition Lyft While Uber opened the frontier for global organized car sharing, with relatively low barriers to entry, competitors such as San Francisco-based Lyft and Chinese company Didi Chuxing (formerly Didi Kuaidi), soon entered the market (see Exhibit 3 for Lyft financials). Lyft was launched in June 2012 by Logan Green and John Zimmer as a service of Zimride, a ridesharing company the two founded in 2007 that focused on longer, city-to-city trips. Lyft, targeted more toward shorter trips, was an app that connected passengers to drivers. Like Uber, Lyft drivers and passengers both rated each other after a ride, which provided reputation information for both drivers and passengers for future "lyfts". 5 In July 2013, Lyft sold Zimride to Enterprise Holdings to focus exclusively on the growth of Lyft. 26 After 2012, Lyft had raised more than $1 billion from high-profile investors such as Alibaba, Rakuten Inc., Coatue, and Andreessen Horowitz, bringing the company valuation to about \$2.5 billion. 27 On January 4, 2016, Lyft announced a partnership with General Motors to achieve a common goal of accelerating their share in the ridesharing market. 28 In order to establish greater trust between passengers and drivers, Lyft implemented several screening processes to ensure the safety and positive experience of their users. All drivers were meticulously screened through a seven-year background check as well as personal interviews with Lyft personnel. Potential drivers were required to hold a driver's license for at least a year and were expected to adhere to Lyft's stringent zero drug or alcohol policies. After they were hired, drivers were eligible for a \$1 million commercial liability insurance policy that could be maintained only by earning excellent ratings from passengers. These insurance benefits were meant to incentivize greater quality of service and discourage unprofessional and inappropriate behavior on the part of the driver (see Exhibit 4 for key differences between Uber and Lyft). 29 Sidecar Founded in 2011, Sidecar not only provided ridesharing services, but also B2B (business-to-business) delivery services. 33 It had reached more than $10 million in funding and was backed by both Google Ventures and Lightspeed Venture Partners. But after facing legal challenges, as well as intense competition from Lyft and Uber, Sidecar moved away from its ridesharing services toward deliveries. By December 29, 2015, Sidecar had lost its battle in the industry and announced that it would be shutting down. The next month, General Motors acquired its assets and intellectual property following its $500 million investment in Lyft. Didi Chuxing Home to one-sixth of the world's population, China was an enormous country with enormous taxi service potential. 34 While Uber wasted no time jumping into this market, local competitors, with their "home court advantage," quickly surpassed Uber's growth. The most formidable competitor in the Chinese market was Didi Chuxing, which also launched in June 2012. Didi Chuxing was the most recent merger between Didi Dache and Kuaidi Dache. 35 Translated directly into English as "drop-drop commuting," Didi Chuxing was Alibaba and Tencent's appbased taxi hiring firm. After just three years, in November 2015, Didi Chuxing was reported to own 83 percent of the market for car hire services in China, with its largest number of apptaxi-hire users. 36 The service also claimed 90 percent market share within Beijing, with more than 1 million ride requests per day. 37 Executives announced in January 2016 that the app had February of 2016 , having raised more than $5 billion in funding. 39 Compared to Uber, Didi Chuxing offered a wider variety of options, including traditional taxi-hailing, carpooling, driver services, and even private bus services. Uber, however, had offered more diverse payment options in China, including Alipay (only for Chinese residents), Baidu Wallet, and Visa or MasterCard, while Didi Chuxing accepted only cash, Alipay (for both locals and foreigners), and WeChat Payment. In September 2015, Didi Chuxing announced a partnership with Lyft, having invested $100 million to assist the two companies in taking on Uber. Concerning the investment, Lyft president John Zimmer called the deal "our first step toward global coverage." It was expected that EXHIBIT 4 Key Differences-Uber \& Lyft 30,31,32 Ridesharing Competition C-199 by May 2016, Lyft users would be able to summon rides through Didi Chuxing's service network, delivering yet another painful blow to Uber's presence in China. Though Zimmer declined to reveal the details of the partnership, it was apparent that Didi and Lyft investors were willing to place money wherever it hurt Uber the most. Tencent, one of Didi's largest investors, had reportedly blocked Uber from its popular messaging app called "WeChat," which held 697 million user accounts in support of both Lyft and Didi Chuxing. As a result, Uber had been losing roughly $1 billion per year in the market. In August 2016, Uber finally waved the white flag of defeat. In a stark signal of how difficult it was for American companies to thrive in China, Uber China sold itself to Didi Chuxing, its fiercest China competitor. Uber China, valued at $7 billion, and Didi Chuxing, 40 valued at $28 billion, combined to form a new company with an approximate value equal to the sum of the two firms. Uber shareholders would receive a 20 percent stake in the new firm. With this deal, Uber joined the ranks of American peers such as eBay and Google, who also had been unsuccessful in establishing and capitalizing on early footholds in China. After its success in China, Didi expanded to other international markets, especially in Latin America, where it had operations in Brazil, Mexico, Costa Rica, Chile, Columbia, and Panama. The company had also expanded to Australia and Russia, launching in Kazan, a city in Tartarstan. 41 Given Didi's success in China and investments in other regions, some observers wondered whether an eventual US market entry by Didi was inevitable. The Taxicab Industry Since the early twentieth century, taxicabs had been transporting city-dwellers from one place to another. The taxicab industry had remained a prevalent force within the transportation industry, both domestically and internationally. The average city-dweller in New York and London spent an average of $238 on taxis annually, resulting in an $11 billion industry. 42,43 With 239,900 drivers nationally, the industry maintained a consistent growth of 3.2 percent from 2009 to 2014. Around 2017, the taxicab segment, in an effort to stay relevant, turned to mobile apps. These ride-hailing apps, designed to compete with the likes of Uber and other ridesharing apps, supported the traditional taxi industry. The apps offered payments and advance bookings for traditional taxis. The leader of these ride-hailing apps, Curb, was responsible for about 10 million trips per month in 2019 compared with Uber's 40 million. Uber's business model dealt a heavy blow to the taxicab industry. Further debilitating the industry was the expensive medallion system to which taxicabs adhered. This medallion system was implemented in 1937 with the intent to control the quality and quantity of taxicabs, help ensure fair wages, and allow the drivers to legally transport passengers. While implemented with good intent, ridesharing technology had brought the system under severe scrutiny, especially considering that the cost of procurement of a medallion ranged from $250,000 each in cities like San Francisco to $1,050,000 in New York. Given this kind of investment, owners had little flexibility in adapting to the new technology of app-based ridesharing. Uber and Lyft drivers did not require such a medallion to operate. 44 Furthermore, estimated hourly earnings for Uber drivers in New York was $23.69, effectively dwarfing the $12.54 average hourly wage of a traditional New York taxicab driver. (see Exhibit 5 for rideshare growth forecast). EXHIBIT 5 Rideshare Growth Forecast. US, 202045 EXHIBIT 6 Estimated Market Share Comparison in Number of Drivers, US, 2020 In response to the disruption of the system, many taxi drivers complained that "These new transportation systems lack the proper insurance, driver training, and passenger liability measures" necessary to operate legally and ethically. 46In its efforts to influence regulations, the taxi industry spent \$3,500 on state legislature lobbying for every $1 spent by Uber, Lyft, and Sidecar (see Exhibit 6 for market share comparison in number of drivers). 47 Uber's Product Portfolio Uber continued to develop and launch new products and services outside of ridesharing services. While the original Uber app was still under development, the company created a think tank consisting of a nuclear physicist, a computational neuroscientist, and a machinery expert who worked on predicting demand for private hire car drivers. 51 The think tank produced some of the most notable and most innovative creations from Uber to date, beginning with uberX in 2012-the original idea allowing local drivers to respond to notifications on the Uber app by driving customers in their own non-luxury. 52 Uber offered its first non-car transportation option in UberChopper, an expensive helicopter service in the Hamptons of New York City, each ride raking up a tab of $3,000.53 In August 2014, Uber launched UberPool, a carpooling service with the intent to reduce fares below that of a typical subway ticket to further capture the price sensitive demographic. 54 And later the same year, Uber released Uber Fresh in Santa Monica, the lunch delivery service that was later rebranded as Uber Eats. 55 The meal delivery service later operated in more than 6,000 cities across 45 countries as a stand-alone app (see Exhibit 7 for a view of the expansion of Uber's service portfolio). 56 EXHIBIT 7 Uber Service Portfolio 57,58,59,60,61 Going Public and Changing Leadership C-201 Going Public and Changing Leadership Uber's performance below expectation at its 2019 public offering-reaching a market cap of $82 billion rather than the promised $120 billion-held a number of explanations. The company had failed to deliver against high expectations due to a number of factors, some of which were of its own making. Tarnished Brand Uber's brand image took a direct blow in the years 2016 to 2019 with an estimated 6,000 sexual assault claims against it. 62 In April 2019, Uber was sued and later settled a \$4.4 million sexual harassment lawsuit in Washington D.C. 63 The attendant rise in safety concerns, especially among female riders, was a factor influencing slowing ride growth. \#DeleteUber In January 2017, a movement was launched on Twitter called \#DeleteUber. 64 The movement emerged from public outrage over Uber's intentions to make a profit in a protest following President Donald Trump's (US President 2017-2021) executive order of banning refugees and immigrants from certain countries. Taxi drivers in New York announced that they would go on strike in response to Trump's ruling and would not pick people up from the JFK airport in order to facilitate the protests. Despite this, various accounts of Uber drivers picking people up from the area began to surface. In response to what many deemed an insensitive and even greedy move by Uber, many protestors deleted the Uber app from their phones and took to Twitter to promote the \#DeleteUber movement. After the protests, Uber attempted to defend itself and tweeted that it had disabled "price surging," a tactic where a company raises prices during times of high demand. Uber claimed to have been misunderstood, but this did not appease the masses. Main Investor Blocks Uber's Expansion Another blow to Uber was seen in the actions of the company's largest investor, Softbank. Softbank led a $100 billion Vision Fund that it used to invest in a variety of companies all over the world. SoftBank had poured capital into technology start-ups including Didi Chuxing, and 99, a transportation start-up in Latin America-both potential competitors to Uber. Softbank's large investments enabled Didi Chuxing and 99 to rapidly expand in Latin America, leaving Uber to fend for itself in the market. This timing could not have been worse for Uber as it had Latin America marked as one of its most promising growth regions. Change of CEO In 2017, due to a number of rising sexual harassment lawsuits against Uber, Travis Kalanick stepped down as CEO of Uber and gave way to Dara Khosrowshahi, the former CEO of Expedia Group. Uber's first, most public encounter with claims of sexism and sexual harassment came from a blogpost published in February 2017 by Susan Fowler, a female engineer who had recently left Uber. 65 The blogpost claimed that a male manager propositioned her soon after she joined the company and that, after reporting the incident, HR dismissed her concerns. However, the blogpost went viral and the CEO, Travis Kalanick, responded forcefully by saying that the behavior Fowler described was "abhorrent and against everything Uber stands for and believes in." 16 He went on to say, "anyone who behaves this way or thinks this is okay will be fired." Despite this, new allegations continued to emerge. The allegations seemed to reveal a culture that was fraught with sexism. One new revelation detailed how an Uber manager told a female engineering recruit that "sexism is systemic in tech," implying in a sense that, "It's okay, everybody does it." 17 The blogpost set off what some considered a reckoning at the company that led to departures of several senior executives and Travis Kalanick (CEO) himself. Senior executives departing during this period included Uber president Jeff Jones, who left because Uber was "incompatible" with his values; Brian McClendon, Uber's vice-president of maps and business platform, who left for politics; and top engineering executive Amit Singhal, who left Uber five weeks after the company announced his appointment. Singhal had failed to disclose that he had left his previous job at Google over a sexual harassment allegation. 68 Dara Khosrowshahi was a logical successor of Kalanick, as both Uber and Expedia were aggregator platforms that connected consumers to clients and ran off of similar software. 69 This was fortunate for Uber in that Khosrowshahi had less of a learning curve when he joined Uber and could instead focus on changing the culture and leading the company into its future. To the employees and investors of Uber, bringing on Khosrowshahi was seen as a muchneeded change as it brought a sense of calm to the company. The new CEO played the role of a flatterer, peacemaker, and diplomat. 70 In negotiation sessions, he was seen as agreeable and non-threatening. 71 According to many of the employees, he was also a good listener to their concerns. 72 All of these attributes were crucial to rescue a company undergoing a fundamental culture change. Expansion of Uber Eats C203 Expansion of Uber Eats In 2014, as one of its key product expansion initiatives, the company launched Uber Eats. Uber Eats had phenomenal success in its initial start. In the food delivery market, Uber Eats saw its market share grow from 3 percent to 27 percent in just 4 years. "When I first joined Uber, I [thought] Uber was much more associated with ride-hailing and Eats was this interesting part-time endeavor," 73 said Khosrowshahi. He went on to say, "It has since exploded, in a good way, into a truly significant business." In 2020, Uber Eats generated \$3.9 billion in revenue, a staggering 178 percent increase from the year before. This growth was spurred by the 66 million worldwide users Uber Eats had amassed. By 2020, Uber Eats controlled 29 percent of the global food delivery market with access to 6,000 cities and over 600,000 supported restaurants. 74 (See Exhibit 8 for U.S. food delivery market share) Despite this explosive growth, however, by the end of 2020 Uber Eats had not generated a profit. The main driver of Uber Eats' rapid demand growth-low delivery fees for customers-also prevented the company from achieving positive margins. The cumulative payments to delivery drivers continued to exceed the cumulative delivery fees paid by consumers. Restaurants, in turn, already low-margin businesses, shouldered large portions of the delivery costs. Analysts estimated that Uber Eats lost approximately $3.36 on every order placed through 2020.76 These losses contributed to net losses of $6.77 billion in 2020.77 While a 20% improvement from 2019 , the staggering losses continued to highlight Uber's need to improve its unit economics. In January 2020, Zomato, an Indian company providing restaurant databases, acquired all of Uber Eats' stock in India, as well as all of Uber Eats' users in India. In exchange, Uber gained a 10% stake in Zomato. 78 Later that month, Uber lost exclusive delivery rights for McDonalds in the UK as new companies entered and moved in on Uber's position. The previous year, Uber also lost exclusive delivery rights with McDonalds in the USA for similar reasons. 79 Despite these setbacks, Uber saw a 30% rise of customers in March 2020.80 Much of this growth was spurred by the onset of the global coronavirus pandemic. The pandemic affected people and industries all over the world and led to mandatory government lockdowns and quarantines. The restaurant industry was severely impacted as most establishments were forced to close normal operations and could only remain open for delivery. An estimated 17% of US restaurants closed down permanently as a result of the pandemic. 81 As expected, the food delivery market surged as customers could order food from their homes. Many customers elected to use food delivery services not only to get food, but also to help support the struggling local restaurants. In 2020 , the number of people using food delivery applications jumped by 25 percent to 1.46 billion, when compared with the year before. 82 In the midst of the demand surge, competitors such as DoorDash went public in December 2020. The pandemic also brought struggles to Uber's original ridesharing business. With government stay-at-home orders in effect and people not needing to travel, the taxi and ridesharing industry struggled. Uber's ridesharing business was down 73 percent in the second quarter of 2020 compared with the year prior. Still plagued with a lack of profitability, Uber was forced to rely on the growth of its food delivery service. In July 2020, Uber acquired Postmates, the food delivery start-up, for $2.65 billion, going all-in on its bid to grow Uber Eats in part to compensate for the downturn in ridesharing. 83 EXHIBIT 8 Food Delivery Service US Market Share 75 In 2015, Merrill Lynch released a report predicting that by 2040, "robotaxis could make up as much as 43 percent of all [car] sales." 84 The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) went so far as to predict that robotaxis would make up " 12 percent of global new car sales" as early as 2035.85 Investment firm ARK's research suggested that the 10-year net present value of the autonomous vehicle market opportunity exceeded $1 trillion in 2020 and could hit $5 trillion by 2024 and $9 trillion by 2029. Of note, ARK was historically bullish on next generation technology bets, using the thesis to make investments. 86 In response to the emerging promise of autonomous vehicles, Uber made early and significant investments in technology development. In February 2015, Uber began collaborating with Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), the leading robotics and autonomous technology university, to establish a new business unit, Uber Advanced Technologies Center, a research facility in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. 87 Much to the chagrin of Carnegie Mellon, Uber hired 40 of Carnegie Mellon's top researchers just two months later, including Chris Urmson, the former head of the Google self-driving car project. 88 The goal was "to replace Uber's more than 1 million human drivers with robot drivers-as quickly as possible." 19 The largest expense for Uber and other ridesharing companies was the drivers themselves, accounting for 80% of the total cost per mile. 90 Autonomous vehicles presented the ability to remove the drivers from the equation, significantly lowering the cost of ridesharing in the long run. A little more than a year later, on September 14, 2016, Uber launched its first fully autonomous self-driving car service to select customers in the Pittsburgh area, including Mayor Bill Beduto. 91 Using landmarks, three-dimensional mapping, and other contextual information, these autonomous vehicles could keep track of their position on the road. Uber maintained a fleet of Ford Fusion vehicles, each equipped with 20 cameras, seven lasers, a GPS, and associated radar equipment to accomplish the job. 92 In July 2016, coinciding with the launch of its self-driving fleet in Pittsburgh, Uber acquired Otto, a 91-employee driverless semi-truck start-up founded earlier that year by a group of top engineers from Apple, Google, and Tesla..93 Included in this elite group of engineers were Anthony Levandowski, a lead engineer in Google's self-driving division; Claire Delaunay, a lead engineer for Google robotics; and Lior Ron, the head of product at Google Maps. 94 With these and the prior CMU hires, Uber commanded the most capable self-driving research group in the world. Developing a self-driving vehicle consisted of two components, the software (the vehicle driving control) and the hardware (the vehicle and associated chips and sensors). Various Uber teams in Pittsburgh, San Francisco, Washington D.C. and Toronto were working on building 3D maps, databases for machines to learn from, and software for "perfect driving." "The ultimate north star for the company is Level 4 autonomy," said Meyhofer, the head of Uber's Advanced Technologies Group (ATG). (See Exhibit 9). In the industry, Level 4 was defined as "attention off" driving-the vehicle could take control under most circumstances a driver encountered and perform all critical functions. Some of these decisions included but were not limited to changing lanes or using a turn signal. Many observers, however, remained skeptical toward the idea of self-driving cars and Uber's ability to cut costs when it came to autonomous vehicles. Level 4 still required a human driver who must be paid. Furthermore, insurance premiums could be significant, as legal car owners could still be responsible for damage caused by inattentiveness at the wheel of their autonomous vehicles. Accidents were definitely possible, as shown in 2018 when 49-year-old Elaine Herzberg was killed on her bicycle by a self-driving Uber car moving at 40 miles per hour with a driver behind the wheel. According to police reports, the car did not slow down at time of impact. 96 Autonomous vehicle competition Uber was not the only company investing in a future of autonomous driving. Tesla had been building autonomous capability into its cars and envisioned a time not far distant in which Tesla owners could download an app and lend their cars to a robotaxi pool as a way of earning revenue on their cars. 97 EXHIBIT 9 Table showing different levels of autonomous vehicles 95 Waymo, a subsidiary of Alphabet Inc, the parent company of Google, had invested heavily in autonomous driving. 98 In 2018, Waymo launched a commercial self-driving car service called "Waymo One" in Phoenix, Arizona. 99 In May 2020, Waymo announced its first outside funding round of $2.25 billion, and in June it partnered with Volvo to integrate Waymo's self-driving technology into its cars. 100 Three years before, Waymo sued Uber and its subsidiary self-driving company, Otto, for allegedly stealing trade secrets and for patent infringement. The company claimed that thousands of car technology files were stolen from Google. 101 Wanting to avoid prolonged controversy, Uber settled the lawsuit, giving Waymo 0.34% of its stock, the equivalent of $245 Million. 102 Uber maintained that it never received any trade secrets from Waymo. Unlike Waymo and other competitors, Uber's strategy seemed to be focused on software rather than hardware. Leveraging the 100-plus million miles that Uber drivers logged each day, the company intended to perfect the software brain of the car..03 "Nobody has set up software that can reliably drive a car safely without a human," Kalanick had said. "We are focusing on that." 104 Indeed, mapping, radar, and navigation capabilities were bottlenecks in self-driving technology. If Uber was able to license the technology out to the highest bidder among automakers desperate to adapt to the impending market shift toward autonomous vehicles, it could be enormously valuable. Conclusion On the heels of the pandemic and a string of significant setbacks, Mr. Khosrowshahi was faced with many questions regarding Uber's future. How could Uber improve the unit economics of its ridesharing and food delivery services and finally turn a profit? Would Uber Eats and other services continue to grow despite the entrance of many new competitors? What other businesses should Uber invest in that could drive long-term profitability? Should Uber continue to invest in the promise of autonomous vehicle software? Ultimately, these and other questions would need to be resolved in order for the company to finally overcome its legacy of operating losses and chart a profitable course into the future. References 1 Farrell, Corrie Driebusch and Maureen. "Uber Prices IPO at $45 a Share". WSJ. 2 https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/15/technology/uber-ipo-price. html. 3https //ycharts.com/companies/UBER/market_cap. 4https //www.nytimes.com/2019/05/03/technology/uber-ipo-ceodara-khosrowshahi-travis-kalanick.html. 5 https://www.forbes.com/sites/liyanchen/2015/09/23/meet-ubersmortal-enemy-how-didi-kuaidi-defends-chinas-home-turf/\#4f80f1396 dce. 83https:// www.nytimes.com/2020/07/05/technology/uber-postmatesdeal.html. 84http:// www.businessinsider.com/driverless-cars-may-lead-to-theend-of-car-ownership-2015-11. 85http:// www.businessinsider.com/driverless-cars-may-lead-to-theend-of-car-ownership-2015-11. 86https ://www.cnbc.com/2020/01/28/ubers-self-driving-cars-are-akey-to-its-path-to-profitability.html. 87http ://fortune.com/2016/03/21/uber-carnegie-mellon-partnership/. 88https ://www.wsj.com/articles/is-uber-a-friend-or-foe-of-carnegiemellon-in-robotics-1433084582. 89http:// www.bloomberg.comews/features/2016-08-18/uber-s-firstself-driving-fleet-arrives-in-pittsburgh-this-month-is06r7on. 90https ://mobility21.cmu.edu/ubers-self-driving-cars-are-a-key-toits-path-to-profitability/. 91https //qz.com/781151/why-is-uber-rushing-to-put-self-driving-carson-the-road-in-pittsburgh/ Accessed July 2017. 93http:// www.bloomberg.comews/features/2016-08-18/uber-s-firstself-driving-fleet-arrives-in-pittsburgh-this-month-is06r7on. Accessed July 2017. 94http:// ww.bloomberg.comews/features/2016-08-18/uber-sfirstself-driving-fleet-arrives-in-pittsburgh-this-month-is06r7on. 95https// www.thecarconnection.comews/1108911_what-are-thedifferent-levels-of-self-driving-cars. 96https ://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/mar/19/ uber-self-driving-car-kills-woman-arizona-tempe. 97 https://techcrunch.com/2019/04/22/tesla-plans-to-launch-arobotaxi-network-in-2020/. 98https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/13/technology/googleparent company-spins-off-waymo-self-driving-car-business.html. 99https ///www.engadget.com/2018-12-05-waymo-one-launches. html. 100https ///www. forbes.com/sites/davidsilver/2020/06/29/waymoand-volvo-form-exclusive-self-driving-partnership/\#1e3e51816adf. 101 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/09/technology/uber-waymo-lawsuit-driverless.html. 102 https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2018/02/waymo-and-uberend-trial-with-sudden-244-million-settlement/. 103http:// www.bloomberg.comews/features/2016-08-18/uber-s-firstself-driving-fleet-arrives-in-pittsburgh-this-month-is06r7on. 104http:// www.bloomberg.comews/features/2016-08-18/uber-s-firstself-driving-fleet-arrives-in-pittsburgh-this-month-is06r7on

Uber, a company providing peer-to-peer shared car rides through a smartphone app, went public at a valuation of $82 billion in May of 2019 , raising $8.1 billion at $45 per share. 1 Prior to this, Uber had announced that it expected to reach a market value of $120 billion at its initial public offering (IPO), which created a frenzy in Silicon Valley and on Wall Street, as Uber would become the biggest American company to initially list on an American stock exchange-larger even than Facebook, which went public in 2012 at an impressive \$104 billion valuation. 2 However, Uber was not able to capitalize on the $120 billion promise and never reached a market cap greater than $82 billion that year. Uber would not exceed its IPO market cap until November of 2020 during a historic run up of the stock market. 3 Dara Khosrowshahi, who had become CEO in 2017, had already faced numerous challenges as he moved the company toward its IPO. Challenges included charges that the culture was rife with sexism, that drivers were involved in hundreds of sexual assaults and other crimes on passengers, and that the company still had not turned a profit. Hired to "clean up the mess" left by former CEO Travis Kalanick, Mr. Khosrowshahi had quietly listened to employees and steadied the ship. 4 Yet, while negative headlines finally began to subside, operating losses continued to expand unabated. That problem was made worse in March 2020 as the global coronavirus pandemic cut demand for rides. Serendipitously, as demand for rides fell, a silver lining emerged in the form of rapidly expanding demand for Uber Eats, the food delivery service owned by the company. The stark ability of one growth business in the portfolio to make up for some of the downturn in another business proved crucial during the pandemic. But Mr. Khosrowshahi also knew that the core business of ridesharing continued to face numerous challenges of regulation, lawsuits, competition, and operating losses. This presented an ongoing need to either find a profitability fix for the core business or to find new businesses that could potentially supersede or replace ridesharing. Beyond food delivery in Uber Eats, another obvious place to look was to autonomous vehicles, which were seen to have the potential to replace drivers with a fleet of robotaxis. Uber had been investing heavily in this area, and yet success in a future vision of autonomous vehicle-based transportation was anything but assured. Other competitors were also investing heavily in the space and no company had yet reached the goal of 100 percent autonomy with its vehicles. As Uber emerged from the worst effects of the pandemic, Mr. Khosrowshahi faced a number of challenges. Could he make the rideshare business profitable and if so, how? Should he continue investing in autonomous vehicles and if so, where? Should he launch new businesses? And crucially, how could he configure and coordinate Uber's portfolio of businesses so as to achieve overall corporate growth and profitability? Uber Company Background While attending the LeWeb conference in Paris, France, old-time friends Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp stumbled upon the idea for Uber. 5 Travis had recently sold his company Red Swoosh to Takamai Technologies for $19 million, and Garrett had sold his company StumbleUpon to eBay for $75 million and was doing "hard time" at a big company. 6 During the conference, these two friends engaged in a pleasant conversation regarding the many inconveniences in life, the most poignant of which was waiting for a taxi in the rain in San Francisco, unable to waive down a vacant one. The entrepreneurs immediately began to brainstorm solutions to this problem. They quickly became convinced that the transportation industry was long overdue for an innovative makeover. Although the details remained clouded, it was clear that the solution needed to be fast and mobile. Following the conference, Garrett spearheaded production of the idea, working earnestly to figure out what an iPhone app might look like and taking the name UberCab for the project. Despite sizable progress, UberCab remained a side project for Garrett, who had again become CEO of StumbleUpon following its spinoff by eBay. This required Kalanick to ramp up his involvement. Taking the role of UberCab's chief incubator, Travis was to run the company temporarily, get the product to prototype, and see Uber through its San Francisco launch. In January 2010 , after $200,000 in seed funding and months of development, UberCab performed its first test run. With three cars cruising the Union Square, Chelsea, and Soho areas, UberCab had officially begun. With only the push of a few buttons, customers could download the Uber app to their phones, submit general personal and credit card information, and "order an Uber" from any location. Each ride required a pickup and drop-off address and in turn provided an estimate of the cost of a customer's trip; all payments were handled through the app. No cash or even tips were exchanged between the driver and the customer during the ride. By the end of March, and with an expanded core team that included Oscar Salazar and Ryan Graves, Uber had successfully performed a beta launch in San Francisco, garnering enough interest to generate $1.25 million in additional funding. By the end of 2011, Uber had raised $44.5 million in funding. That same year, the company changed its name from UberCab to Uber. In May 2011, Uber commenced its aggressive expansion plans, opening in New York, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. (see Exhibit 1 for Uber rides by dity over time). The company EXHIBIT 1 Uber Rides by City over Time 8 Note: Drivers making at least one trip in the specified month continued to expand in smaller US cities, as well as overseas markets throughout 2012-2013, building a presence in European cities, including Paris and London, as well as Toronto, Canada, and Sydney, Australia, and later moving into the Asian cities of Seoul, South Korea, Beijing, China, and New Delhi, India. In India, Uber launched a new pricing option known as uberX, a lower-cost alternative in which the passenger was picked up by a driver in a typically modest sedan. 7 Uber also expanded to less-developed countries, including Mexico, Pakistan, and Nigeria. As Uber pursued multiple international markets, the ridesharing company quickly encountered a multitude of lawsuits, competitors, and idiosyncrasies of local transportation markets. Spain, two cities in India, Berlin, Milan, Sao Paulo, and other cities banned the service. 9 Taxicab drivers all over the world called for a ban against Uber in their cities as well, in some cases organizing large-scale protests and even bringing lawsuits against the company. 10 By 2015, Uber was engaged in 173 lawsuits within the United States alone, as well as a litany of foreign government backlashes including raids in the Netherlands, a criminal trial of two top executives in France, proposed new regulations in London and Toronto, and an all-out ban of all services in Rio de Janeiro. 11 Many of these lawsuits and outcries were attributed to illegal actions by Uber-employed drivers, such as sexual assault, theft, and even murder, casting a negative light on the overall image of the innovative company. 12 Furthermore, Lyft, a new entrant in 2012, had successfully muscled its way into a position of 20 percent market share. 13 By branding itself as a more community-oriented and friendly alternative to Uber, Lyft made a more trustworthy impression on the international community, even partnering with Chinese powerhouse corporations Alibaba and Tencent to produce the China-operated Didi Kuai to compete directly with Uber in China. 14 In spite of the competition and controversy, by early 2016, the popular ridesharing app had close to 8 million users in 58 countries and more than 300 cities worldwide. Speaking at a private event in Vancouver, British Columbia in early 2016, Travis Kalanick, made a solemn admission. Because of fierce competition in the Chinese market, he announced, Uber suffered losses of more than $1 billion in 2015. 15 The following years for Uber saw continued losses across its services. Indeed, through 2020 , despite rapid growth in revenues, Uber faced the reality that its operating losses also continued, having increased year over year to over $8 billion in 2019 (See Exhibit 2). EXHIBIT? Ihar Financials 16 *2019 Uber changes accounting policies regarding reportable segments. Eats and Grocery delivery are merged into a single segment: Deliver. History of the Sharing Economy The success of Uber was part of the rise of what had been dubbed the "sharing economy," the concept that each person possessed unemployed assets that could be rented to peers through a coordination mechanism, such as a smartphone app. With the smartphone boom came a massive drop in coordination costs, which made the possibility of sharing or renting personal assets an increasingly convenient reality. In addition to cars, the sharing economy promoted a wide variety of asset sharing, including homes, washing machines, office space, surfboards, loft storage, boats, lawn mowers, and even cocktail dresses. 17 The sharing economy had grown at an astonishing rate. Airbnb, founded in 2008, totaled 155 million guest stays by 2014, whereas Hilton Worldwide, founded in 1919, reached only 127 million total guest stays by the same year. 18 Projections by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC) showed that global revenues from the top sharing economy sectors could jump from $15 billion in 2016 to $335 billion by 2025.19 Beyond Airbnb, which offered more than 250,000 rooms in more than 30,000 cities in 192 countries, many other firms in the sharing economy had extensive offerings. 20 Within retail sharing, Yerdle (now called Trove) was an app designed to enable people to give away their "stuff" for credits on the app, which could then be used to buy other peoples' "stuff."21 Similarly, Poshmark promoted the exchange of unwanted clothing, essentially allowing users to shop other users' closets. 22 While these companies were expected to achieve high growth rates in the subsequent ten years, many complications arose for firms in the sharing economy. In a survey of end customers who had tried the sharing economy, 57 percent agreed that they were intrigued about the idea, but held reservations and concerns about some of the companies; 72 percent believed that the sharing economy experience was not "consistent"; 69 percent refused to use sharing economy companies until they were given a positive recommendation by a trusted acquaintance. 23 Ridesharing Competition Lyft While Uber opened the frontier for global organized car sharing, with relatively low barriers to entry, competitors such as San Francisco-based Lyft and Chinese company Didi Chuxing (formerly Didi Kuaidi), soon entered the market (see Exhibit 3 for Lyft financials). Lyft was launched in June 2012 by Logan Green and John Zimmer as a service of Zimride, a ridesharing company the two founded in 2007 that focused on longer, city-to-city trips. Lyft, targeted more toward shorter trips, was an app that connected passengers to drivers. Like Uber, Lyft drivers and passengers both rated each other after a ride, which provided reputation information for both drivers and passengers for future "lyfts". 5 In July 2013, Lyft sold Zimride to Enterprise Holdings to focus exclusively on the growth of Lyft. 26 After 2012, Lyft had raised more than $1 billion from high-profile investors such as Alibaba, Rakuten Inc., Coatue, and Andreessen Horowitz, bringing the company valuation to about \$2.5 billion. 27 On January 4, 2016, Lyft announced a partnership with General Motors to achieve a common goal of accelerating their share in the ridesharing market. 28 In order to establish greater trust between passengers and drivers, Lyft implemented several screening processes to ensure the safety and positive experience of their users. All drivers were meticulously screened through a seven-year background check as well as personal interviews with Lyft personnel. Potential drivers were required to hold a driver's license for at least a year and were expected to adhere to Lyft's stringent zero drug or alcohol policies. After they were hired, drivers were eligible for a \$1 million commercial liability insurance policy that could be maintained only by earning excellent ratings from passengers. These insurance benefits were meant to incentivize greater quality of service and discourage unprofessional and inappropriate behavior on the part of the driver (see Exhibit 4 for key differences between Uber and Lyft). 29 Sidecar Founded in 2011, Sidecar not only provided ridesharing services, but also B2B (business-to-business) delivery services. 33 It had reached more than $10 million in funding and was backed by both Google Ventures and Lightspeed Venture Partners. But after facing legal challenges, as well as intense competition from Lyft and Uber, Sidecar moved away from its ridesharing services toward deliveries. By December 29, 2015, Sidecar had lost its battle in the industry and announced that it would be shutting down. The next month, General Motors acquired its assets and intellectual property following its $500 million investment in Lyft. Didi Chuxing Home to one-sixth of the world's population, China was an enormous country with enormous taxi service potential. 34 While Uber wasted no time jumping into this market, local competitors, with their "home court advantage," quickly surpassed Uber's growth. The most formidable competitor in the Chinese market was Didi Chuxing, which also launched in June 2012. Didi Chuxing was the most recent merger between Didi Dache and Kuaidi Dache. 35 Translated directly into English as "drop-drop commuting," Didi Chuxing was Alibaba and Tencent's appbased taxi hiring firm. After just three years, in November 2015, Didi Chuxing was reported to own 83 percent of the market for car hire services in China, with its largest number of apptaxi-hire users. 36 The service also claimed 90 percent market share within Beijing, with more than 1 million ride requests per day. 37 Executives announced in January 2016 that the app had February of 2016 , having raised more than $5 billion in funding. 39 Compared to Uber, Didi Chuxing offered a wider variety of options, including traditional taxi-hailing, carpooling, driver services, and even private bus services. Uber, however, had offered more diverse payment options in China, including Alipay (only for Chinese residents), Baidu Wallet, and Visa or MasterCard, while Didi Chuxing accepted only cash, Alipay (for both locals and foreigners), and WeChat Payment. In September 2015, Didi Chuxing announced a partnership with Lyft, having invested $100 million to assist the two companies in taking on Uber. Concerning the investment, Lyft president John Zimmer called the deal "our first step toward global coverage." It was expected that EXHIBIT 4 Key Differences-Uber \& Lyft 30,31,32 Ridesharing Competition C-199 by May 2016, Lyft users would be able to summon rides through Didi Chuxing's service network, delivering yet another painful blow to Uber's presence in China. Though Zimmer declined to reveal the details of the partnership, it was apparent that Didi and Lyft investors were willing to place money wherever it hurt Uber the most. Tencent, one of Didi's largest investors, had reportedly blocked Uber from its popular messaging app called "WeChat," which held 697 million user accounts in support of both Lyft and Didi Chuxing. As a result, Uber had been losing roughly $1 billion per year in the market. In August 2016, Uber finally waved the white flag of defeat. In a stark signal of how difficult it was for American companies to thrive in China, Uber China sold itself to Didi Chuxing, its fiercest China competitor. Uber China, valued at $7 billion, and Didi Chuxing, 40 valued at $28 billion, combined to form a new company with an approximate value equal to the sum of the two firms. Uber shareholders would receive a 20 percent stake in the new firm. With this deal, Uber joined the ranks of American peers such as eBay and Google, who also had been unsuccessful in establishing and capitalizing on early footholds in China. After its success in China, Didi expanded to other international markets, especially in Latin America, where it had operations in Brazil, Mexico, Costa Rica, Chile, Columbia, and Panama. The company had also expanded to Australia and Russia, launching in Kazan, a city in Tartarstan. 41 Given Didi's success in China and investments in other regions, some observers wondered whether an eventual US market entry by Didi was inevitable. The Taxicab Industry Since the early twentieth century, taxicabs had been transporting city-dwellers from one place to another. The taxicab industry had remained a prevalent force within the transportation industry, both domestically and internationally. The average city-dweller in New York and London spent an average of $238 on taxis annually, resulting in an $11 billion industry. 42,43 With 239,900 drivers nationally, the industry maintained a consistent growth of 3.2 percent from 2009 to 2014. Around 2017, the taxicab segment, in an effort to stay relevant, turned to mobile apps. These ride-hailing apps, designed to compete with the likes of Uber and other ridesharing apps, supported the traditional taxi industry. The apps offered payments and advance bookings for traditional taxis. The leader of these ride-hailing apps, Curb, was responsible for about 10 million trips per month in 2019 compared with Uber's 40 million. Uber's business model dealt a heavy blow to the taxicab industry. Further debilitating the industry was the expensive medallion system to which taxicabs adhered. This medallion system was implemented in 1937 with the intent to control the quality and quantity of taxicabs, help ensure fair wages, and allow the drivers to legally transport passengers. While implemented with good intent, ridesharing technology had brought the system under severe scrutiny, especially considering that the cost of procurement of a medallion ranged from $250,000 each in cities like San Francisco to $1,050,000 in New York. Given this kind of investment, owners had little flexibility in adapting to the new technology of app-based ridesharing. Uber and Lyft drivers did not require such a medallion to operate. 44 Furthermore, estimated hourly earnings for Uber drivers in New York was $23.69, effectively dwarfing the $12.54 average hourly wage of a traditional New York taxicab driver. (see Exhibit 5 for rideshare growth forecast). EXHIBIT 5 Rideshare Growth Forecast. US, 202045 EXHIBIT 6 Estimated Market Share Comparison in Number of Drivers, US, 2020 In response to the disruption of the system, many taxi drivers complained that "These new transportation systems lack the proper insurance, driver training, and passenger liability measures" necessary to operate legally and ethically. 46In its efforts to influence regulations, the taxi industry spent \$3,500 on state legislature lobbying for every $1 spent by Uber, Lyft, and Sidecar (see Exhibit 6 for market share comparison in number of drivers). 47 Uber's Product Portfolio Uber continued to develop and launch new products and services outside of ridesharing services. While the original Uber app was still under development, the company created a think tank consisting of a nuclear physicist, a computational neuroscientist, and a machinery expert who worked on predicting demand for private hire car drivers. 51 The think tank produced some of the most notable and most innovative creations from Uber to date, beginning with uberX in 2012-the original idea allowing local drivers to respond to notifications on the Uber app by driving customers in their own non-luxury. 52 Uber offered its first non-car transportation option in UberChopper, an expensive helicopter service in the Hamptons of New York City, each ride raking up a tab of $3,000.53 In August 2014, Uber launched UberPool, a carpooling service with the intent to reduce fares below that of a typical subway ticket to further capture the price sensitive demographic. 54 And later the same year, Uber released Uber Fresh in Santa Monica, the lunch delivery service that was later rebranded as Uber Eats. 55 The meal delivery service later operated in more than 6,000 cities across 45 countries as a stand-alone app (see Exhibit 7 for a view of the expansion of Uber's service portfolio). 56 EXHIBIT 7 Uber Service Portfolio 57,58,59,60,61 Going Public and Changing Leadership C-201 Going Public and Changing Leadership Uber's performance below expectation at its 2019 public offering-reaching a market cap of $82 billion rather than the promised $120 billion-held a number of explanations. The company had failed to deliver against high expectations due to a number of factors, some of which were of its own making. Tarnished Brand Uber's brand image took a direct blow in the years 2016 to 2019 with an estimated 6,000 sexual assault claims against it. 62 In April 2019, Uber was sued and later settled a \$4.4 million sexual harassment lawsuit in Washington D.C. 63 The attendant rise in safety concerns, especially among female riders, was a factor influencing slowing ride growth. \#DeleteUber In January 2017, a movement was launched on Twitter called \#DeleteUber. 64 The movement emerged from public outrage over Uber's intentions to make a profit in a protest following President Donald Trump's (US President 2017-2021) executive order of banning refugees and immigrants from certain countries. Taxi drivers in New York announced that they would go on strike in response to Trump's ruling and would not pick people up from the JFK airport in order to facilitate the protests. Despite this, various accounts of Uber drivers picking people up from the area began to surface. In response to what many deemed an insensitive and even greedy move by Uber, many protestors deleted the Uber app from their phones and took to Twitter to promote the \#DeleteUber movement. After the protests, Uber attempted to defend itself and tweeted that it had disabled "price surging," a tactic where a company raises prices during times of high demand. Uber claimed to have been misunderstood, but this did not appease the masses. Main Investor Blocks Uber's Expansion Another blow to Uber was seen in the actions of the company's largest investor, Softbank. Softbank led a $100 billion Vision Fund that it used to invest in a variety of companies all over the world. SoftBank had poured capital into technology start-ups including Didi Chuxing, and 99, a transportation start-up in Latin America-both potential competitors to Uber. Softbank's large investments enabled Didi Chuxing and 99 to rapidly expand in Latin America, leaving Uber to fend for itself in the market. This timing could not have been worse for Uber as it had Latin America marked as one of its most promising growth regions. Change of CEO In 2017, due to a number of rising sexual harassment lawsuits against Uber, Travis Kalanick stepped down as CEO of Uber and gave way to Dara Khosrowshahi, the former CEO of Expedia Group. Uber's first, most public encounter with claims of sexism and sexual harassment came from a blogpost published in February 2017 by Susan Fowler, a female engineer who had recently left Uber. 65 The blogpost claimed that a male manager propositioned her soon after she joined the company and that, after reporting the incident, HR dismissed her concerns. However, the blogpost went viral and the CEO, Travis Kalanick, responded forcefully by saying that the behavior Fowler described was "abhorrent and against everything Uber stands for and believes in." 16 He went on to say, "anyone who behaves this way or thinks this is okay will be fired." Despite this, new allegations continued to emerge. The allegations seemed to reveal a culture that was fraught with sexism. One new revelation detailed how an Uber manager told a female engineering recruit that "sexism is systemic in tech," implying in a sense that, "It's okay, everybody does it." 17 The blogpost set off what some considered a reckoning at the company that led to departures of several senior executives and Travis Kalanick (CEO) himself. Senior executives departing during this period included Uber president Jeff Jones, who left because Uber was "incompatible" with his values; Brian McClendon, Uber's vice-president of maps and business platform, who left for politics; and top engineering executive Amit Singhal, who left Uber five weeks after the company announced his appointment. Singhal had failed to disclose that he had left his previous job at Google over a sexual harassment allegation. 68 Dara Khosrowshahi was a logical successor of Kalanick, as both Uber and Expedia were aggregator platforms that connected consumers to clients and ran off of similar software. 69 This was fortunate for Uber in that Khosrowshahi had less of a learning curve when he joined Uber and could instead focus on changing the culture and leading the company into its future. To the employees and investors of Uber, bringing on Khosrowshahi was seen as a muchneeded change as it brought a sense of calm to the company. The new CEO played the role of a flatterer, peacemaker, and diplomat. 70 In negotiation sessions, he was seen as agreeable and non-threatening. 71 According to many of the employees, he was also a good listener to their concerns. 72 All of these attributes were crucial to rescue a company undergoing a fundamental culture change. Expansion of Uber Eats C203 Expansion of Uber Eats In 2014, as one of its key product expansion initiatives, the company launched Uber Eats. Uber Eats had phenomenal success in its initial start. In the food delivery market, Uber Eats saw its market share grow from 3 percent to 27 percent in just 4 years. "When I first joined Uber, I [thought] Uber was much more associated with ride-hailing and Eats was this interesting part-time endeavor," 73 said Khosrowshahi. He went on to say, "It has since exploded, in a good way, into a truly significant business." In 2020, Uber Eats generated \$3.9 billion in revenue, a staggering 178 percent increase from the year before. This growth was spurred by the 66 million worldwide users Uber Eats had amassed. By 2020, Uber Eats controlled 29 percent of the global food delivery market with access to 6,000 cities and over 600,000 supported restaurants. 74 (See Exhibit 8 for U.S. food delivery market share) Despite this explosive growth, however, by the end of 2020 Uber Eats had not generated a profit. The main driver of Uber Eats' rapid demand growth-low delivery fees for customers-also prevented the company from achieving positive margins. The cumulative payments to delivery drivers continued to exceed the cumulative delivery fees paid by consumers. Restaurants, in turn, already low-margin businesses, shouldered large portions of the delivery costs. Analysts estimated that Uber Eats lost approximately $3.36 on every order placed through 2020.76 These losses contributed to net losses of $6.77 billion in 2020.77 While a 20% improvement from 2019 , the staggering losses continued to highlight Uber's need to improve its unit economics. In January 2020, Zomato, an Indian company providing restaurant databases, acquired all of Uber Eats' stock in India, as well as all of Uber Eats' users in India. In exchange, Uber gained a 10% stake in Zomato. 78 Later that month, Uber lost exclusive delivery rights for McDonalds in the UK as new companies entered and moved in on Uber's position. The previous year, Uber also lost exclusive delivery rights with McDonalds in the USA for similar reasons. 79 Despite these setbacks, Uber saw a 30% rise of customers in March 2020.80 Much of this growth was spurred by the onset of the global coronavirus pandemic. The pandemic affected people and industries all over the world and led to mandatory government lockdowns and quarantines. The restaurant industry was severely impacted as most establishments were forced to close normal operations and could only remain open for delivery. An estimated 17% of US restaurants closed down permanently as a result of the pandemic. 81 As expected, the food delivery market surged as customers could order food from their homes. Many customers elected to use food delivery services not only to get food, but also to help support the struggling local restaurants. In 2020 , the number of people using food delivery applications jumped by 25 percent to 1.46 billion, when compared with the year before. 82 In the midst of the demand surge, competitors such as DoorDash went public in December 2020. The pandemic also brought struggles to Uber's original ridesharing business. With government stay-at-home orders in effect and people not needing to travel, the taxi and ridesharing industry struggled. Uber's ridesharing business was down 73 percent in the second quarter of 2020 compared with the year prior. Still plagued with a lack of profitability, Uber was forced to rely on the growth of its food delivery service. In July 2020, Uber acquired Postmates, the food delivery start-up, for $2.65 billion, going all-in on its bid to grow Uber Eats in part to compensate for the downturn in ridesharing. 83 EXHIBIT 8 Food Delivery Service US Market Share 75 In 2015, Merrill Lynch released a report predicting that by 2040, "robotaxis could make up as much as 43 percent of all [car] sales." 84 The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) went so far as to predict that robotaxis would make up " 12 percent of global new car sales" as early as 2035.85 Investment firm ARK's research suggested that the 10-year net present value of the autonomous vehicle market opportunity exceeded $1 trillion in 2020 and could hit $5 trillion by 2024 and $9 trillion by 2029. Of note, ARK was historically bullish on next generation technology bets, using the thesis to make investments. 86 In response to the emerging promise of autonomous vehicles, Uber made early and significant investments in technology development. In February 2015, Uber began collaborating with Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), the leading robotics and autonomous technology university, to establish a new business unit, Uber Advanced Technologies Center, a research facility in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. 87 Much to the chagrin of Carnegie Mellon, Uber hired 40 of Carnegie Mellon's top researchers just two months later, including Chris Urmson, the former head of the Google self-driving car project. 88 The goal was "to replace Uber's more than 1 million human drivers with robot drivers-as quickly as possible." 19 The largest expense for Uber and other ridesharing companies was the drivers themselves, accounting for 80% of the total cost per mile. 90 Autonomous vehicles presented the ability to remove the drivers from the equation, significantly lowering the cost of ridesharing in the long run. A little more than a year later, on September 14, 2016, Uber launched its first fully autonomous self-driving car service to select customers in the Pittsburgh area, including Mayor Bill Beduto. 91 Using landmarks, three-dimensional mapping, and other contextual information, these autonomous vehicles could keep track of their position on the road. Uber maintained a fleet of Ford Fusion vehicles, each equipped with 20 cameras, seven lasers, a GPS, and associated radar equipment to accomplish the job. 92 In July 2016, coinciding with the launch of its self-driving fleet in Pittsburgh, Uber acquired Otto, a 91-employee driverless semi-truck start-up founded earlier that year by a group of top engineers from Apple, Google, and Tesla..93 Included in this elite group of engineers were Anthony Levandowski, a lead engineer in Google's self-driving division; Claire Delaunay, a lead engineer for Google robotics; and Lior Ron, the head of product at Google Maps. 94 With these and the prior CMU hires, Uber commanded the most capable self-driving research group in the world. Developing a self-driving vehicle consisted of two components, the software (the vehicle driving control) and the hardware (the vehicle and associated chips and sensors). Various Uber teams in Pittsburgh, San Francisco, Washington D.C. and Toronto were working on building 3D maps, databases for machines to learn from, and software for "perfect driving." "The ultimate north star for the company is Level 4 autonomy," said Meyhofer, the head of Uber's Advanced Technologies Group (ATG). (See Exhibit 9). In the industry, Level 4 was defined as "attention off" driving-the vehicle could take control under most circumstances a driver encountered and perform all critical functions. Some of these decisions included but were not limited to changing lanes or using a turn signal. Many observers, however, remained skeptical toward the idea of self-driving cars and Uber's ability to cut costs when it came to autonomous vehicles. Level 4 still required a human driver who must be paid. Furthermore, insurance premiums could be significant, as legal car owners could still be responsible for damage caused by inattentiveness at the wheel of their autonomous vehicles. Accidents were definitely possible, as shown in 2018 when 49-year-old Elaine Herzberg was killed on her bicycle by a self-driving Uber car moving at 40 miles per hour with a driver behind the wheel. According to police reports, the car did not slow down at time of impact. 96 Autonomous vehicle competition Uber was not the only company investing in a future of autonomous driving. Tesla had been building autonomous capability into its cars and envisioned a time not far distant in which Tesla owners could download an app and lend their cars to a robotaxi pool as a way of earning revenue on their cars. 97 EXHIBIT 9 Table showing different levels of autonomous vehicles 95 Waymo, a subsidiary of Alphabet Inc, the parent company of Google, had invested heavily in autonomous driving. 98 In 2018, Waymo launched a commercial self-driving car service called "Waymo One" in Phoenix, Arizona. 99 In May 2020, Waymo announced its first outside funding round of $2.25 billion, and in June it partnered with Volvo to integrate Waymo's self-driving technology into its cars. 100 Three years before, Waymo sued Uber and its subsidiary self-driving company, Otto, for allegedly stealing trade secrets and for patent infringement. The company claimed that thousands of car technology files were stolen from Google. 101 Wanting to avoid prolonged controversy, Uber settled the lawsuit, giving Waymo 0.34% of its stock, the equivalent of $245 Million. 102 Uber maintained that it never received any trade secrets from Waymo. Unlike Waymo and other competitors, Uber's strategy seemed to be focused on software rather than hardware. Leveraging the 100-plus million miles that Uber drivers logged each day, the company intended to perfect the software brain of the car..03 "Nobody has set up software that can reliably drive a car safely without a human," Kalanick had said. "We are focusing on that." 104 Indeed, mapping, radar, and navigation capabilities were bottlenecks in self-driving technology. If Uber was able to license the technology out to the highest bidder among automakers desperate to adapt to the impending market shift toward autonomous vehicles, it could be enormously valuable. Conclusion On the heels of the pandemic and a string of significant setbacks, Mr. Khosrowshahi was faced with many questions regarding Uber's future. How could Uber improve the unit economics of its ridesharing and food delivery services and finally turn a profit? Would Uber Eats and other services continue to grow despite the entrance of many new competitors? What other businesses should Uber invest in that could drive long-term profitability? Should Uber continue to invest in the promise of autonomous vehicle software? Ultimately, these and other questions would need to be resolved in order for the company to finally overcome its legacy of operating losses and chart a profitable course into the future. References 1 Farrell, Corrie Driebusch and Maureen. "Uber Prices IPO at $45 a Share". WSJ. 2 https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/15/technology/uber-ipo-price. html. 3https //ycharts.com/companies/UBER/market_cap. 4https //www.nytimes.com/2019/05/03/technology/uber-ipo-ceodara-khosrowshahi-travis-kalanick.html. 5 https://www.forbes.com/sites/liyanchen/2015/09/23/meet-ubersmortal-enemy-how-didi-kuaidi-defends-chinas-home-turf/\#4f80f1396 dce. 83https:// www.nytimes.com/2020/07/05/technology/uber-postmatesdeal.html. 84http:// www.businessinsider.com/driverless-cars-may-lead-to-theend-of-car-ownership-2015-11. 85http:// www.businessinsider.com/driverless-cars-may-lead-to-theend-of-car-ownership-2015-11. 86https ://www.cnbc.com/2020/01/28/ubers-self-driving-cars-are-akey-to-its-path-to-profitability.html. 87http ://fortune.com/2016/03/21/uber-carnegie-mellon-partnership/. 88https ://www.wsj.com/articles/is-uber-a-friend-or-foe-of-carnegiemellon-in-robotics-1433084582. 89http:// www.bloomberg.comews/features/2016-08-18/uber-s-firstself-driving-fleet-arrives-in-pittsburgh-this-month-is06r7on. 90https ://mobility21.cmu.edu/ubers-self-driving-cars-are-a-key-toits-path-to-profitability/. 91https //qz.com/781151/why-is-uber-rushing-to-put-self-driving-carson-the-road-in-pittsburgh/ Accessed July 2017. 93http:// www.bloomberg.comews/features/2016-08-18/uber-s-firstself-driving-fleet-arrives-in-pittsburgh-this-month-is06r7on. Accessed July 2017. 94http:// ww.bloomberg.comews/features/2016-08-18/uber-sfirstself-driving-fleet-arrives-in-pittsburgh-this-month-is06r7on. 95https// www.thecarconnection.comews/1108911_what-are-thedifferent-levels-of-self-driving-cars. 96https ://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/mar/19/ uber-self-driving-car-kills-woman-arizona-tempe. 97 https://techcrunch.com/2019/04/22/tesla-plans-to-launch-arobotaxi-network-in-2020/. 98https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/13/technology/googleparent company-spins-off-waymo-self-driving-car-business.html. 99https ///www.engadget.com/2018-12-05-waymo-one-launches. html. 100https ///www. forbes.com/sites/davidsilver/2020/06/29/waymoand-volvo-form-exclusive-self-driving-partnership/\#1e3e51816adf. 101 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/09/technology/uber-waymo-lawsuit-driverless.html. 102 https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2018/02/waymo-and-uberend-trial-with-sudden-244-million-settlement/. 103http:// www.bloomberg.comews/features/2016-08-18/uber-s-firstself-driving-fleet-arrives-in-pittsburgh-this-month-is06r7on. 104http:// www.bloomberg.comews/features/2016-08-18/uber-s-firstself-driving-fleet-arrives-in-pittsburgh-this-month-is06r7on Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started