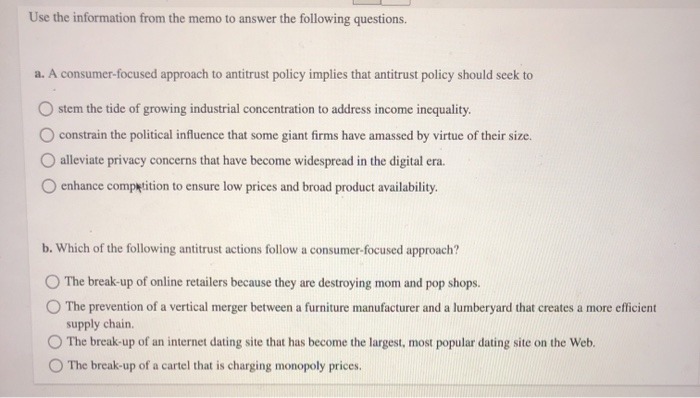

Question

Case assignments must be completed with a written study on the assigned case questions in the textbook. The format requested for these assignments is based

Case assignments must be completed with a written study on the assigned case questions in the textbook. The format requested for these assignments is based on elaborating and including two basic parts in the essay: 1) in a bullet presentation style (one phrase each bullet), list a summary of the key issues, situations, problems, opportunities and threats you may identify as relevant; 2) answer all the questions listed in each case in two or three sound paragraphs.

Case: Zara's Disruptive Vision: Data-Driven Fast-Fashion

Apparel and textile are one of the largest industries in the world. It employs approximately 75 million people and generates more than US$3 trillion in transactions. Its activities are global in scale and scope; design, branding, fiber production, fabric cutting, assembly, finishing work, logistics, merchandising, and marketing functions circle the world. Traditionally, big retailers drive the market, determining what to make, where to make it, how to distribute it, and then, how to sell it. Operationally, global apparel companies and national retailers outsource apparel production via global brokers, such as Li & Fung. The latter, for instance, supplies billions of pieces of apparel to department stores, hypermarkets, specialty stores, and e-commerce sites worldwide. It owns no fabric mills, no sewing machines, and no clothing factories. Rather, Li & Fung oversees a network of 15,000 suppliers spanning 60 countries that can make virtually any clothing article. Historically, the typical garment maker is a small-scale, labor-intensive operation, usually located in a low-wage country that employs a few to a few dozen workers. There, workers make specific pieces of apparel, often in a narrow range of sizes and colors, which global brokers then integrate with the output of hundreds of other such companies that span dozens of countries. As more companies in more countries make more specialized products (i.e., one factory makes zippers, one makes linings, one makes buttons, and so on), global brokers perform as cross-border intermediaries and supervise the logistics and assembly of components into finished goods. Ultimately, these goods are distributed to apparel retailers worldwide. Responding to ever-changing fashion, markets relentlessly pressure apparel retailers to have the right style in the right sizes in the right quantities at the right time for the right price. In turn, they press global brokers to improve coordination among the many different players. By planning collections closer to the selling season, testing the market, placing smaller initial orders, and reordering more frequently, retailers can reduce forecasting errors and avoid the dreaded "death by inventory." Industry wisdom and historic practice spurred apparel firms, no matter how big or small, to choose a "sliver" of a particular activity (i.e., make zippers, manage logistics, focus on retail operations) instead of creating value across multiple slivers. Effectively, the global apparel industry pressed firms to see the strategy in terms of 'doing what you do best and outsourcing the rest. Steadily, globalization resets the global apparel industry. Fewer barriers, better logistics, and improving technologies create paths to disrupt industry standards. That is, rather than accepting the determinism of industry structure, some managers bet on revolutionary visions and radical missions. A compelling example is the compression of cycle times in the apparel-buyer chain. Traditionally, moving a garment from designer to brokers to factories to shops takes approximately six months?three to design a new collection and another three to make and ship it. Now, a few companies, notably H&M, have cut the cycle to three to five months. One, Zara, has slashed the cycle to a phenomenal two weeks. Zara's vision of data-driven fast-fashion, by outright rejection of sacred rules about strategy and success, has disrupted long-running principles and practices in the apparel industry. For instance, unlike its rivals, Zara makes most of what it sells, shuns advertising, avoids sales, and directs distribution and delivery. These choices, once seen as heresies, have propelled Zara to the world's leading apparel company and made its founder, Amancio Ortega, the world's second-wealthiest person with a fortune of nearly $70 billion.

Effectively disrupting a global industry requires radically rethinking what customers want, how you make and market it, and how you make money doing so. Zara, in starting and sustaining the data-driven fast-fashion revolution, translates its vision into a practical strategy through a range of ingenious choices in acquiring resources, developing capabilities, and creating competencies. Separately and collectively, this anchor Zara's competitiveness.Making and selling fast fashion calls for an exquisitely tuned set of technological expertise, designers, manufacturing systems, logistic know-how, and retail locations. Progressively, Zara has developed world-class resources in these functions. Zara, as does virtually every other apparel firm, sources finished garments, like generic t-shirts, slips, and the like, from suppliers in Europe, North Africa, and Asia. Unlike its rivals, Zara employs more than 20,000 people, distributed across 23 factories circling La Corua, to make more than half of its fashion garments. Zara's production prowess stems from Ortega's insight that exploiting short-lived fashion trends requires speedy designs and decision? which, operationally, means making items close to home. Hence, Zara makes millions of its most time- and fashion-sensitive products in its own state-of-the-art factories on its own schedule based on its own market data that are then fed into its own logistic system to quickly deliver them to its own storefronts. Garments flow through Zara's distribution center in La Corua?about the size of 90 football fields?or smaller satellite centers in Brazil and Mexico. In La Corua, garments travel along 125 miles of underground rails that link their factories. Along the way, they are sorted in carousels capable of processing 45,000 folded garments per hour. Zara ships more than 2.5 million items per week to its stores worldwide. Custom orders reach its stores in Europe, the Middle East, and much of the United States in 24 hours, and 48 hours for Asia and Latin America. If there is marketing at Zara, it's done via high-profile real estate. "We invest in prime locations. We place great care in the presentation of our storefronts. That is how we project our image" explained Director Luis Blanc. Zara's stores command high-profile slots in premier shopping venues such as the Champs-Elyses in Paris, Regent Street in London, Fifth Avenue in New York, and Nanjing Road in Shanghai. The opening photo, for example, showcases Zara's flagship storefront in Barcelona. Its location strategy has created interesting tensions. Noted a consultant, "Prada wants to be next to Gucci, Gucci wants to be next to Prada. The retail strategy for luxury brands is to try to keep as far away from the likes of Zara. Zara's strategy is to get as close to them as possible." Building factories and opening shops set the firm's resources. Managers' insight into how best to bundle them to come up with an activity in a way that is integrative, consistent, and productive creates capabilities. Expectedly, Zara shines in translating ordinary aspects of a firm, such as factories and shops, into formidable capabilities. Zara's designers gather data from store managers, industry publications, TV, Internet, and films. Its trend spotters focus on university campuses and nightclubs. Its slaves-to- fashion staff snaps photos at couture shows and posts them to headquarters. There, designers sift the data, quickly converting the latest, greatest looks into affordable, hot fashion for the masses. Zara often translates a fashion trend from a catwalk in Paris to a blouse or ensemble ready for sale in Shanghai in as little as two weeks; its rivals, notably Gap and H&M, take months to do the same. For example, when Madonna played a series of concerts in Spain, teenage girls arrived at her final show sporting a Zara knockoff of the outfit that she had worn during her first show. Zara's real-time sense of what people want to wear lets it tap the convergence of fashion and taste across national boundaries. It does not adapt products to a particular country's preferences but looks to standardize its designs for the global market. Executives reason that offering customers an affordable, quality garment with an edgy vibe, in effect a hard-to-resist value proposition, globalizes fashion trends. Attractive stores, both inside and out, are vital to Zara's mystique. Explains Luis Blanc, "We want our clients to enter a beautiful store where they are offered the latest fashions. We want our customers to understand that if they like something, they must buy it now because it won't be in the shops the following week. It is all about creating a climate of scarcity and opportunity." Fitting in with fancy neighbors, like Prada and Gucci, requires that Zara put its best face forward. Retail specialists roam the globe, adjusting window displays, testing store ambiance, and rethinking presentation schemes. Just as layouts are always changing, so too is the look of the inventory mix. Zara rejects the idea of conventional spring and fall clothing collections in favor of "live collections" that are designed, manufactured, and sold almost as quickly as customers' fleeting tastes?no style lasts more than four weeks. Zara's product policy emphasizes reasonable quality, affordability, and high fashion. It has little use for advertising or promotion. Amancio Ortega saw advertising as a "pointless distraction"; he himself has never given an interview and rarely allows his picture to be taken. Zara spends just 0.3 percent of sales on advertising, compared with 3 to 4 percent for most fashion retailers. It avoids flashy campaigns, relying instead on word-of-mouth among loyal shoppers. Like its founder, it does not promote itself; it leaves that to thrilled customers. Just as bright managers combine resources into capabilities, they also transform capabilities into core competencies. Somewhat difficult to pinpoint, one can think of core competency as the special outlook, skill, or technology that, by synthesizing links between resources and capabilities, sets and sustains the firm's ability to create superior value for its customers. Zara has a quick turnaround on fashion trends?many items you see in its stores didn't exist a few weeks earlier. Explains Director Marcos Lopez, "The key driver in our stores is the right fashion. Price is important, but it comes second." Zara aggressively prices its products and adjusts pricing for the international market, making customers in foreign markets bear the costs of shipping products from Spain. Likewise, if the product line fails to excite customers, Zara can "scrap an entire production line if it is not selling. We can dye collections in new colors, and we can start a new fashion line in days." Integrating new ideas and new designs into reasonably priced, high-fashion garments that are available worldwide within two weeks is an awfully hard task. Zara's capacity to blend its resources and capabilities successfully develops a value-creating, hard-to-copy competency?perhaps best seen in its rivals' struggles to do so. Zara's stores, besides presenting its face to the world, function as grassroots marketing agents. Networked stores feed sales data and customer requests (the latter helping to localize otherwise globally standardized products) to headquarters in La Corua. At the center of the Zara-web, physically and symbolically, is "The Cube," the gleaming central command of the company. Here, designers, operations folks, and strategic planners bundle and blend resources and capabilities, experimenting with ways to leverage real-time data into real-time fashions. Designers, for instance, simulate product presentation and positioning (even testing the acoustics of the in-store soundtrack) on its "Fashion Street," a Potemkinesque strip of mock storefronts that mimic the layout of its strategically significant storefronts around the world. Constant and continual refinement of resources and capabilities fortifies Zara's competencies. Clothes Shopping as an Exciting Adventure Zara's timeliness of its offerings, the aura of exclusiveness, captivating in-store ambiance, and positive word of mouth, fed by rapid product turnover, leverage various resources and capabilities. Loyal shoppers learn which days of the week the latest, greatest fashions are delivered?so-called "Z-days"?and shop accordingly. Zara fuels the frenzy with small shipments?say, three or four dresses in a particular style?to a store. Small shipments make for sparsely stocked shelves. Moreover, products have a display limit of one month. Rapid turnover does the rest: even though consumers visit Zara frequently when they return, things look different. The CEO of the National Retail Federation, reflecting on Z-days, rapid turnover, and sparse inventory, marveled, "It's like you walk into a new store every two weeks." The first Zara shop opened its doors in 1975 in La Corua. Today, there are more than 2,000 outlets and, on average, a new one opens every day. The elegant clarity of Zara's vision, mission, and strategy, translated into a compelling set of resources, capabilities, and competencies, supports its stunning success. Impressive in its own right, Zara's choice to be great rejected the contrary imperatives of long-established strategic standards in the global apparel industry. Presently, no other apparel company comes close to designing, making, moving, and selling fashion as speedily as Zara. Its success leaves rivals with less time to figure out how to better configure and coordinate their operations. Some stay in the game, such as H&M, while others fall further behind, notably Gap. Ultimately, struggling rivals must follow Zara's strategic lead?if they don't, warns a leading retail analyst, they "won't be in business in 10 years."

Questions

12-1. Which element of Zara's strategy do you believe best explains its success?

12-2. Assess the difficulty a competitor, such as Gap, faces trying to re-create the resources, capabilities, and core competencies that define Zara.

question b.

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started