At the beginning of 2019, Southwest Airlines fared third in the rankings of the best U.S. Airlines released by the Wall Street Journal. Delta Airlines

At the beginning of 2019, Southwest Airlines fared third in the rankings of the best U.S. Airlines released by the Wall Street Journal. Delta Airlines ranked first and Alaska Airlines ranked second. These rankings were based on a composite set of parameters forming a scorecard. South- west did best on two- hour tarmac delays and worst on mishandled baggage (see tabel 1). The Dallas-based airline, famously known for its highly efficient and successful “low- cost” operations, seemed to face other challenges as well. It paid millions over the past decade to settle safety violations. This included fines for flying planes that needed repairs. In the past nine years, there were at least two incidents where the roofs of Southwest planes opened up inflight.

The worst incident took place in April 2018. One of the engines on Southwest Flight 1380 blew apart at 32,000 feet over Pennsylvania. Jennifer Riordan, a 43-year-old mother of two, was blown partway out of a broken window. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) said a fan blade that had snapped off the engine was showing signs of metal fatigue. Later, the NTSB chairman, Robert Sumwalt, said that the engine in the flight was missing a fan blade. This incident resulted in one fatality and seven others were also hurt. In another incident in 2016, an engine on a South- west jet blew apart over Florida. This was also attributed to metal fatigue, or wear and tear, hurling debris that struck the fuselage and tail. No one was hurt in that incident.

Further, the union that represented its mechanics accused Southwest Airlines of pressuring their maintenance workers to cut corners to keep planes flying. A Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) investigation of these whis- tleblower complaints found mistrust of management to the extent of hurting the airline’s safety.

Another development in the industry that also threat- ened the company’s low-cost position was the advent of the “Ultra Low Cost Carriers” (ULCC). These carriers are even more bare-bones and keep their basic fares very low, thus eroding Southwest’s low-price advantage. They, of course, charge extra for everything including baggage handling. As the investigation into the deadly engine failure con- tinued, Southwest Chairman and CEO, Gary Kelly, was faced with several questions regarding its low-cost business model.

Tabel 1 U.S. Airlines Rankings Released at the Beginning of January 2019

Southwest Airlines began in response to an entrepreneurial opportunity that existed for low-cost, hassle-free travel between the cities of Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio— the Golden Triangle that was experiencing rapid economic and population growth during the late 1960s. Rollin King, a San Antonio entrepreneur who owned a small commuter air service, and Herb Kelleher, a New Jersey–born, New York University Law School graduate who moved to San Antonio in 1967 to practice law, pooled the seed money to start Southwest Airlines in response to this opportunity. After an initial rough four years caused by the major airlines, Southwest got its flights to takeoff in 1971 with Dallas Love Field as its base and it crossed every major benchmark in the following years. It remained the consistently profitable discount carrier year after year and became a major airline in 1990 by crossing the $1 billion revenue mark. Focused on the business travelers who needed to be “on-time, every time,” its business model had several intriguing elements. For example, by-passing the traditional “hub-and-spoke” configuration and offering short-haul, point-to-point airline service allowed savings on fundamentals such as gate fees because they could fly out of secondary airports; additional savings were through elimination of other fringe services like no assigned seats, no meals, no baggage transfers, or few or no reservations through travel agents. The choice of operating a new and uniform fleet of aircraft saved mainte- nance costs and facilitated optimum utilization of human resources. Brilliant fuel hedges resulted in huge cost savings for years. In addition, the charismatic leadership of Herb Kelleher, and a strong company culture and incentives focused on tight cost-control, made Southwest a legendary airline.

In 2004, the leadership transitioned to Gary Kelly, a long-term employee and the former Chief Financial Officer of Southwest Airlines. The same year, Kelly heralded a se- ries of initiatives to put the airline on a high-growth trajec- tory. These included the code-sharing agreements beginning with ATA (in response to AirTran eyeing the Chicago mar- ket), a move into the Philadelphia market (a stronghold of USAir), and kicking off a campaign to repeal the Wright Amendment* that could boost Southwest’s ability to fly uninterrupted services out of its traditional fort, Dallas Love Field airport.

In 2007, a new fare structure was introduced that included Business Select, which gave customers the option of priority in boarding. With a new $40 fee that allowed cus- tomers to be among the first 15 passengers to board the plane, this new fare structure was definitely targeted at woo- ing some of the business travelers who wanted a little more than no frills. However, with this move, Southwest managed to irritate some of its most loyal customers. While South- west continued its bags-fly-free policy, which had contrib- uted to increasing its market share, Kelly declared “never say never” when probed about his company’s plans to start charging baggage check-in fees in 2013. Southwest introduced an in-flight entertainment portal with free live and on- demand television, offering 20 live channels and 75 television episodes from popular series. It also introduced Internet access for $8 a day per device on Wi-Fi-enabled aircraft.

While all these were significant departures from the origi- nal Southwest business model, there were two other important strategic changes initiated in Kelly’s regime. The first was ex- pansion into the international markets that began in Decem- ber 2008 when the company agreed to provide an online link to WestJet’s booking portal to help its customers book flights to Canada. Later, Southwest formally filed an application with the Department of Transportation for the right to fly its own planes to Canada. As of January 2019, the company had operations to over 14 destinations internationally. A significant chunk of the company’s revenues came from international operations—approximately $595 million of the operating revenues in 2017, $383 million in 2016, and $287 million in 2015, respectively, were attributable to foreign operations. The re- mainder of the operating revenues, approximately $20.6 billion in 2017, $20.0 billion in 2016, and $19.5 billion in 2015, respec- tively, were attributable to domestic operations.

The second most significant departure was moving away from the organic growth strategy with the acquisition of AirTran Holdings Inc., the parent company of AirTran Airways (AirTran), for a combination of $1.4 billion cash and Southwest Airlines common stock. The acquisition, an- nounced in September 2010, was only the third in South- west’s history. It gave the discounter its first service in Atlanta, a Delta Air Lines fortress for decades, and more flights from New York and Washington, DC.

Little more than a year after the transaction officially closed, Southwest was dehubbing AirTran’s Atlanta hub and conceding markets to Delta. AirTran’s Atlanta hub had been Southwest’s motivation in acquiring AirTran, in addition to further pushing into international markets.

“To make that shift in strategy has taken a huge effort, but as a leading domestic carrier, it was time ’that we think about stepping out,’” said Kelly. Following what could possibly be the slow- est merger in history, Southwest successfully completed it on December 28, 2014, when the last AirTran f light f lew, retracing its original Atlanta-to-Tampa route of October 1993 (AirTran was called ValueJet at that time). “The com- pany expected total acquisition and integration costs to be approximately $550 million (before profit sharing and taxes) upon completing the transition of AirTran 717-200s† out of the fleet in 2015,” said company officials.

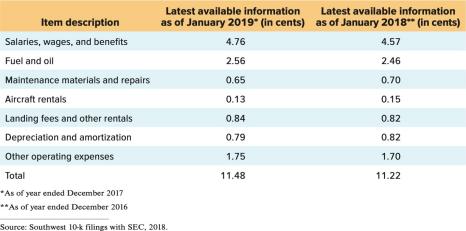

Table 2 Cost Structure

At approximately 41 percent of total company operating expenses, salaries, wages, and benefits expenses were Southwest’s largest operating costs. The terms of its collective bargaining agreements limited the company’s ability to reduce these costs.9 Approximately 83 percent of its labor force was unionized. These employees had pay scale increases as a result of contractual rate increases.

Additionally, there were new collective bargaining agreements ratified during 2016 with the majority of Southwest’s unionized employees, including its pilots and flight attendants, among others. Meanwhile, other unionized employees, including its mechanics and material specialists were also in negotia- tions for labor agreements for the last six years. In Septem- ber 2017, Southwest Airlines mechanics rejected a proposed contract offer that fell short of the pay rates they wanted. While Southwest described the pay rates and retirement benefits in the proposed contract as industry leading, union leaders had opinions otherwise. According to the union leaders, the contract did not measure up to the higher his- torical rates Southwest mechanics earned relative to the rest of the industry and it did not do enough to compensate members for their industry-leading productivity.10 Any changes to the contract terms could put additional burden on the low-cost competitive position.

Jet fuel and oil represented approximately 22 percent of the company’s operating expenses as of the beginning of 2019 and represented the second largest operating cost (see table 2). The cost of fuel could be extremely volatile and unpredictable and fluc- tuated due to several factors beyond the company’s control, for example, conflicts and hostilities in oil producing areas, problems in domestic refining or pipeline capacity due to adverse weather conditions and natural disasters, or changes in currency exchange rates. Southwest’s ability to effectively address fuel price increases and pass them to the consumers could be limited by factors such as its historical low-fare reputation, the portion of its customer base pur- chasing travel for leisure purposes, and the risk that higher fares will drive a decrease in demand. This risk could partly be managed by utilizing over-the-counter fuel derivative instruments to hedge a portion of its future jet fuel pur- chases. However, energy prices could fluctuate significantly in a relatively short amount of time. Since the company used a variety of different derivative instruments at differ- ent price points, there was an inherent risk that the fuel derivatives it used would not provide adequate protection against significant increases in fuel prices and could in fact result in hedging losses. For a long time, the company also benefitted from accounting standards in the United States. It faced the risk that its fuel derivatives would not be effec- tive or that they would no longer qualify for hedge accounting under applicable accounting standards. This problem could have been severe without the recent increases in shale oil production in the United States.

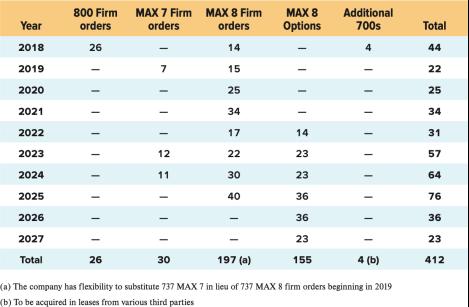

Several efforts were underway to reduce fuel consumption and improve fuel efficiency. Southwest started modernizing its fleet and also initiated other fuel initiatives. It was the first airline company in North America to offer scheduled service utilizing Boeing’s new 737 MAX 8 aircraft. This aircraft en- tered service in fourth quarter 2017. The Boeing 737 MAX 8 was expected to significantly reduce fuel use and CO2 emis- sions. There were 13 Boeing 737 MAX 8 aircraft in its fleet by the end of 2017. Southwest was also the launch customer for the Boeing 737 MAX 7 series aircraft, with deliveries ex- pected to begin in 2019. It had placed firm orders for 197 of 737 MAX 8 aircraft and 30 of 737 MAX 7 aircraft (see Table 3). These aircrafts would also have lower maintenance costs since they are new and they are unlikely to in- crease training costs since they are all large Boeing 737 aircrafts, continuing the Boeing 737 tradition at Southwest.

Table 3 Southwest Airlines Firm Deliveries and Options for Boeing 737-700, 737-800, 737 MAX 7, and 737 MAX 8 Aircraft

With moderate improvement in economic conditions over the last few years and an increased focus on costs by most airlines, competition has intensified in the airline industry. Southwest faced tough competition from major U.S. airlines, including American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, and United Airlines‡ and other low- cost competitors, including JetBlue Airways. Southwest competed with these other airlines on virtually all of its scheduled routes. In addition, a new category of ultra-low cost carriers (ULCCs), for example, Frontier and Spirit Air- lines, emerged as a credible threat (Refer to table1).

The ULCCs represented a completely different ap- proach to the traditional air travel model. While similar to the disruptive innovation like Southwest Airlines in its initial stages when converting non-users to users of air travel the ULCCs are yet significantly different in several ways. Allegiant Airlines perfected this model offering low-fare, high-value vacation packages from secondary airports to points in Florida and to Las Vegas.

The revenue stream for a ULCC was not based on air tickets, the core revenue for low-cost airlines like Southwest, but on purchase of ancillary products such as hotel and tour packages. The model evolved to be even less dependent on vacation/leisure travel. A ULCC aimed to stimulate travel decisions by offering very low fares and providing a nonstop routing where there was none, even if only for a few times a week. By offering a high value-to-cost equation for the consumer, these airlines aimed to divert discretionary dollars into air travel.

Unlike Southwest, the ULCCs were not in the business of connecting people and destinations. The stimulant of de- mand in the ULCC model was fares and not the need to get to a destination. Typically, a ULCC entered markets that it thought had latent potential, offered several flights, and then monitored the results. If the expectations about traffic materialized, it offered more services at that airport. If expectations did not materialize or the traffic was less productive than at other points, the ULCC moved out quickly. With the exception of some operations by Frontier at Denver, these airlines did not have their own turf nor did they operate connecting hubs. In this model, airplanes were moved around the country when opportunities were spotted. ULCC flight schedules fitted their fleet availability and not necessarily in timings that were most preferred by customers.

Alongside Allegiant, Frontier, Spirit, and Sun Country were the other prominent players in this genre. They repre- sented about 7 percent of all U.S. airline departing seats by late 2018 and were expected to grow to over 12 percent by 2020. As of January 2019, Southwest Airlines offered services to over 100 destinations throughout the United States, Mexico, and the Caribbean. It operated more than 3,800 flights a day including more than 500 roundtrip markets.13 Its interna- tional footprint expanded to over 14 destinations covered through 16 international gateway cities. The company remained profitable as of 2018. It made significant technology investments and completed its single largest technology proj- ect in its history in the recent years to completely transition its reservation system to the Amadeus Altéa Passenger Ser- vice System. The new reservation system was designed to improve flight scheduling and inventory management. It would enable operational enhancements to manage flight dis- ruptions, such as those caused by extreme weather condi- tions. Additional international growth and other foundational and operational capabilities were expected to get a boost.14 The company continued to invest in technology to optimize other aspects of its operations. The progressive moderniza- tion of its fleet was also expected to facilitate cost control.

Nevertheless, the mid-seat rankings suggested Southwest faced stiff competition from both the traditional carriers and the ULCCs. The company’s stock was down by 20 percent in 2018. The concerns about its planes and people continued. Amidst increasing fuel cost concerns, the company was expected to slow its expansion plans and capacity.

Case written by Professors Naga Lakshmi Damaraju, Sonoma State University, Alan Eisner, Pace University, and Gregory Dess, The University of Texas at Dallas.

QUESTION:

1. How would you describe the vision and mission of the company above? You can check the company's annual report from the company's website. Based on the above case study, explain and describe the I/O model in detail? Based on the story above, how do you see the role of the CEO of the company, related to the company's vision and mission and implementation of the I/O model, and managing the company's stakeholders? Explain!

2. Explain in your opinion, how do management act in managing their customers? Do you see a unique situation for Southwest Airlines? What about the company's situation, both externally and internally in supporting their customers? Are there any issues/issues that you would like to consider in the airline industry in managing its customers?

3. The competition of airlines is always interesting to analyze. Based on the story above, and you can also explore this case yourself, illustrates the competition that Southwest companies are facing. Do you think the company can outperform the competition?

4.Companies as business entities must create value propositions. Based on question no. 3 how should companies create new value propositions? Should the company do a merger or acquisition with another airline company? How would you like to make the Southwest different?

Rank Overall Extreme On-time Cancelled arrivals number rank flights delays Delta Delta Delta Alaska Southwest Alaska Alaska Spirit Delta Alaska Southwest Spirit Alaska Southwest Frontier Spirit Spirit American Delta United JetBlue JetBlue JetBlue United American Frontier American 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Spirit JetBlue* United United' American Frontier American JetBlue Frontier Frontier Southwest Southwest United 2-hour tarmac delays Mishandled Involuntary baggage bumping Complaints Spirit Delta Southwest JetBlue JetBlue Alaska Delta United Delta United American JetBlue Alaska Southwest United Frontier Alaska American Southwest Spirit Spirit American Frontier Frontier

Step by Step Solution

3.60 Rating (189 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

The vision and mission of Southwest Airlines are not explicitly mentioned in the provided case study However based on common knowledge about the company its vision could be to become the most loved lo...

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started