Question

CLEARLY: ORGANIZING FOR OMNICHANNEL RETAILING In mid-January 2017, Roy Hessel was meeting with this marketing team. Hessel was the chief executive officer (CEO) of Clearly,

CLEARLY: ORGANIZING FOR OMNICHANNEL RETAILING

In mid-January 2017, Roy Hessel was meeting with this marketing team. Hessel was the chief executive

officer (CEO) of Clearly, Canada's leading online optical products company. Hessel and his team were

discussing the company's participation in an upcoming eyewear show in Milan, Italy. Held annually in

late February, the International Exhibition of Optics, Optometry and Ophthalmology (abbreviated as

MIDO1 in Italian) was the world's largest eyewear exhibition. The event provided more than 1,000

optical companies an opportunity to showcase their latest offerings.

Clearly planned to make statements on three fronts at MIDO 2017: its eyeglasses were now fashionable as

well as functional; it was now a design powerhouse in its own right; and it was transforming the retail

experience for its customers.

Hessel was also the president responsible for online initiatives at Essilor International SA (Essilor), a

global manufacturer of optical lenses headquartered in Paris, France. In February 2014, Essilor had

acquired Clearly, an online pure-play company,2 and converted it into its own online division. These

moves on the part of both companies were part of an ongoing retail trend known as omnichannel retailing.

The market for eyewear was growing. For example, a study by the industry research journal

Ophthalmology had shown that half of the world's population would be short-sighted by 2050,3 which

suggested that there would potentially be nearly five billion consumers by then. In Canada, 30 per cent of

the population, or 10.9 million consumers, were known to have myopia in 2016.4 But as of 2016, only 4

per cent of consumers in Canada were fulfilling their vision-correction needs online, according to Hessel.

In spite of the high potential for new customer acquisition and the growing influence of the digital world,

the rate of annual growth in online sales of optical products was slow. For example, the online sales of

eyeglasses and contact lenses in the United States was forecast to grow at an average annual rate of

3.4 per cent over the five-year period from 2016 to 2021.5

Hessel wondered how to approach this challenge:

How do we increase online sales beyond the current 4 per cent of industry sales? As an online

company, I want to bring the remaining 96 per cent of consumers online. That would be likely if

online companies and eye-care practitioners (ECPs), traditionally fierce competitors, collaborate

with one another. Technology and omnichannel are both enablers of industry-wide collaboration.

But both online optical companies and ECPs need to break out of a deeply entrenched mindset of

rivalry. How do we do it? That is the question my team and I have been asking as we head to

Milan.

OMNICHANNEL RETAILING

Traditionally, retailers operated within brick-and-mortar or physical spaces where they provided direct

access to products on display for customers walking into the stores. The physical medium was well-suited

for products with both display and service requirements. The advent of the Internet in 1995 led to the

launch of online pure-plays across several product categories: books, electronics, music, movies, and

office supplies, to name a few.

Brick-and-mortar retailers were beginning to lose sales because online prices were lower. A 2013 survey

of specialty fashion retailers by the global consultancy firm Deloitte had shown, for example, that selling

costs averaged 33 per cent of sales for store formats and dropped to 13 per cent of sales when the same

product was ordered online.6 Customers were catching on. They would examine merchandise at physical

stores and proceed to purchase online in a trend known as showrooming. In a parallel trend called

webrooming, customers researched products online but visited a physical store to make the purchase. This

was particularly evident in categories like shoes, sports equipment, and cosmetics. Omnichannel retailing

was the result of the convergence of the two trends.

Omnichannel retailing was also a logical evolution of what was known as multi-channel retailing,

wherein companies sold simultaneously through several channels, such as physical stores, websites,

kiosks, direct mail and catalogues, call centres, social media, mobile devices, gaming consoles, television,

networked appliances, and home service. However, each of these channels was an independent silo;

customers in a channel had no clue about the events in other channels, and retailers were also clueless

about the shopping behaviour of individual customers in different channels.

Hessel noted how omnichannel retailing differed:

In omnichannel retailing, a customer can switch channels?buy online and pick up in-store, or

use mobile in-store to research or make a purchase, or buy in-store and make a return online. The

retailer also gets a 360-degree view of a customer's purchases across all channels. Two core enabling the customer to order online and pick up in-store and [enabling the customer] to buy in-

store and return online.

Omnichannel retailing not only bridged the gap between traditional and online transactions, but it also

brought unique competitive advantages to both. A retailer's multi-channel shoppers spent an average of

15-30 per cent more than one-channel shoppers. However, a retailer's omnichannel shoppers spent 15-30

per cent more than multi-channel consumers.7 Consumers who were provided with a seamless experience

across channels shopped more frequently and made more purchases across product categories. In Canada,

online sales were forecast to reach $34 billion8

by 2018, which represented 5.3 per cent of retail sales; this

was short of the average for all G-20 nations, where online sales represented 6.0 per cent of retail sales.9

The reasons for slow growth were Canada's large geographical size and sparse population, which made

distribution costly.

A 2014 study on omnichannel shopping preferences by the consulting firm A.T. Kearney revealed that

over 90 per cent of people still preferred to shop in person. Despite the increasing trend of consumers

using smartphones to research products and prices, 61 per cent of the consumers A.T. Kearney surveyed

noted that they "highly valued" asking a sales associate for product recommendations, and 72 per cent of

consumers were also "inclined" to ask a sales associate if another store had a product in stock. Only

28 per cent preferred to fulfil these needs themselves via their mobile devices.10

Online retailers were establishing storefronts in order to build customer relationships, engage in real-time

market research, and provide hands-on assistance to those consumers who were wary of shopping online.

Consumers saw physical locations not only as stores, but also as spaces where opinions, reviews, social

media, touch-and-feel experiences, and technology combined to create seamless connections. Two

examples were noteworthy: Amazon, the world's largest e-tailer, had launched a storefront in October

2014 in New York City and was on the verge of opening its second storefront at a mall near the

University of California in San Diego.11 It had plans to set up more storefronts to manage inventory

pertaining to same-day delivery and product returns. Warby Parker, an American online eyeglass

company founded in 2010, had opened its first storefront in 2013 and followed up with eight more in the

United States within a year. Each Warby Parker storefront featured full-length mirrors and photo

booths.12

OPTICAL PRODUCTS INDUSTRY

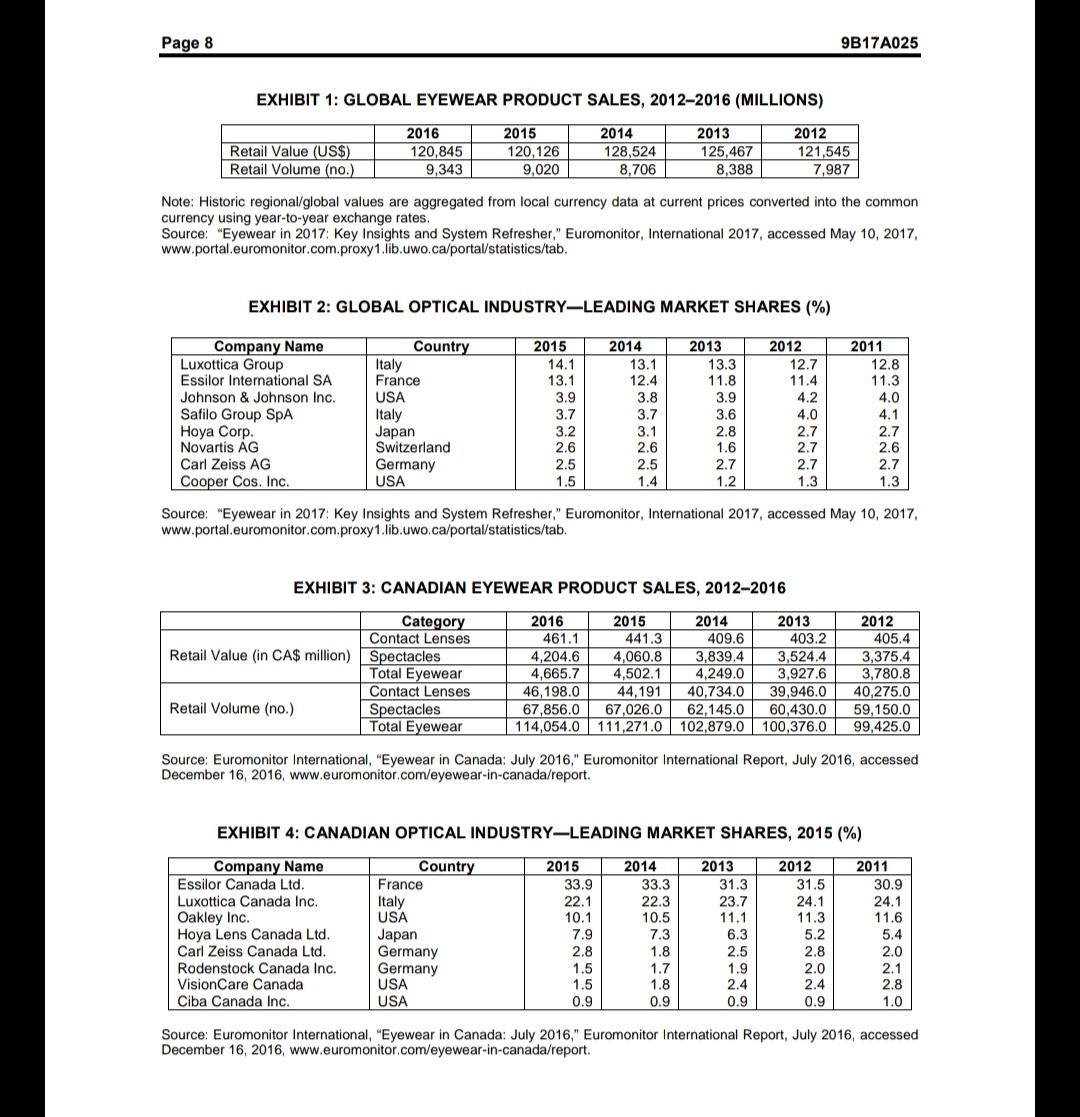

Globally, the optical products industry had revenues of $120.8 billion in 2016 (see Exhibit 1). It had

grown at a rate of 0.6 per cent over 2015 but was forecast to grow at 3-4 per cent per annum over the period up to 2021. It was segmented into two major categories: contact lenses and spectacles. Each

category had several subcategories. Luxottica Group SpA, based in Milan, Italy, was the industry leader,

with a 14.1 per cent market share worldwide in 2015 (see Exhibit 2).

The optical products industry in Canada had revenues of $4.7 billion in 2016 (see Exhibit 3). It had grown

at 3.6 per cent over 2015 and was forecast to grow at about the same rate per annum over the period up to

2021. Essilor Canada was the industry leader in Canada, with a 33.9 per cent market share in 2015 (see

Exhibit 4).

Independent ECPs held about 50 per cent of the market share for overall vision care, but they were a

fragmented lot, consisting of many small players. Prior to the arrival of online players led by Clearly,

independent ECPs had competed only with retail chains owned by optical corporations that employed

ECPs of their own. In recent years, however, independent ECPs faced competition from a new source:

mass merchandisers. Wal-Mart and Costco, for example, had replicated the tried and tested model of

independent ECPs in their stores. Their ability to leverage scale to offer lower prices and an efficient

retail ambiance posed a significant threat to independent ECPs.

ECPs were the first point of contact for eyewear consumers in the optical ecosystem. They conducted eye

examinations and provided customers with prescriptions, for which they charged a fee. This fee was a

steady source of income for EPCs. Their second source of income was the sale of eyewear, which was

conveniently linked with the prescription. Customers could choose to buy their prescribed eyewear

directly from the examining ECP, rather than from a retail store, mass merchandiser, or online. Another

major source of revenue for ECPs, particularly in the United States, was managed vision care providers.

These sources brought in referrals from small and large businesses that bore the cost of healthcare for

their employees. ECPs were also the distribution channel for the industry, accounting for 73 per cent of

eye-care patients by volume, worldwide.

Independent ECPs had several competitive advantages over both corporate chains and mass

merchandisers. One advantage was the depth of their relationships with individual patients, which

resulted in patients returning to the ECP for their next eye exams, recommendations to others, and overall

customer satisfaction rate. Independent ECPs were also quick to adapt to new technology. They ran lean

operations and had lower staff turnover. They also provided a critical touch-and-feel experience to

customers.

Said Hessel,

The role of ECPs is central to the ecosystem of optical retailing. The process of buying eyeglasses

starts with an annual eye exam, which can be performed only by an ECP. In ensuring healthy

vision, a goal in which everyone has a stake, ECPs are thus irreplaceable. ECPs represent the

standard to which optical retailers in general must aspire. Their sense of detail, commitment,

passion, and personal connection to individual consumers is a competitive advantage that large

retailers or corporate chains cannot replicate.

The main disadvantages of ECPs, however, were a lack of online capabilities and an inability to scale up.

The arrival of e-commerce had the potential to change the traditional model of ECPs altogether. Online

prices were as much as 70 per cent lower than the prices offered by ECPs. Online sourcing offered price

transparency, a hitherto unfamiliar aspect of optical retailing. It also offered convenience. However, the

touch-and-feel factor that ECPs enjoyed was a feature that online companies could not match. Online

retailers were therefore relying on technology to up their ante.

For example, consumers could opt for virtual fittings, wherein they could record a video of themselves as

they tried on different spectacle frames and sunglasses and see a 180-degree view of the eyewear as they

"wore" it. This facility was offered by companies like 4Care GmbH in Germany, Ditto Technologies Inc.

in the United States, and ACEP in France, which had acquired TryLive in November 2015.13 These

companies also had a provision for crowdsourcing advice: users could view and vote for favourite

eyewear fittings online, and when an individual user had received sufficient votes, they would receive an

email from the company informing them of which pair the general public thought looked best on them.

Some online companies, such as Warby Parker, offered online customers up to five frames for a no-cost

trial for a period of five days.14 After the trial period, customers could ship frames back to the online

retailer, again at no cost. Although this initiative was effective, the cost to the retailer was clearly a

concern.

CLEARLY: COMPANY BACKGROUND

The company was founded in October 2000 as Coastal Contacts by Roger Hardy, a Vancouver-based

entrepreneur. Having worked earlier in the optical industry, Hardy knew that eyewear was an expensive

consumer product because it was padded with retail markups and could therefore be sold at lower prices,

and he was convinced that the disintermediation of online retailing would reduce prices further.

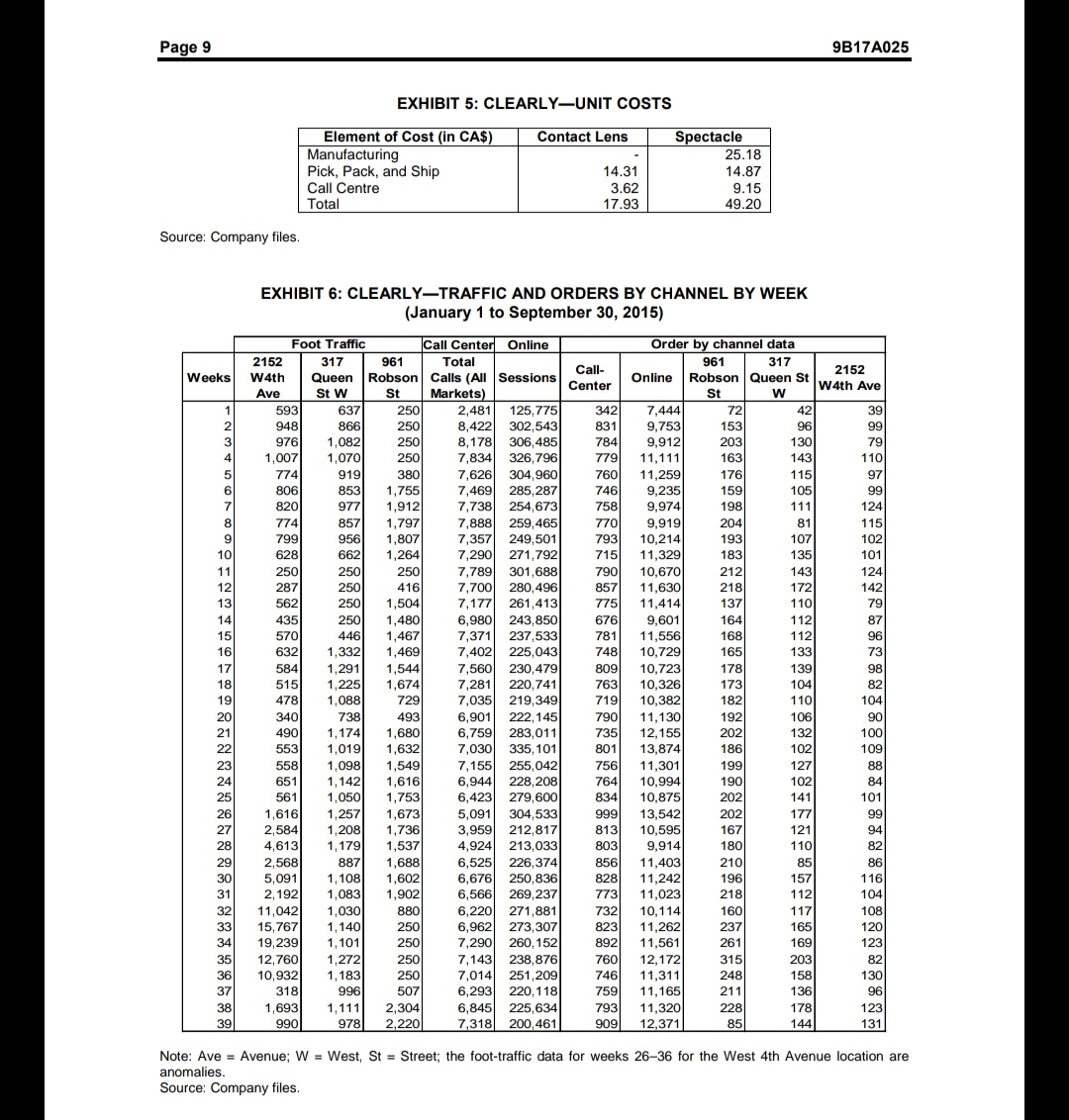

Contact lenses were ideal for online retailing because they did not require elaborate fitting. They also cost

less than spectacles to deliver to customers, as Clearly learned in later years (see Exhibit 5). The start-up

recorded $1 million in revenue in its first year of operations by changing the way consumers could buy

contact lenses. The company had three call centres: one each in Vancouver, Manila, and Tokyo. The

Tokyo call centre focused on the Japanese market, where the company had a distribution centre, while the

other two serviced a global market. In 2008, the company moved into the sale of eye glasses and spectacle

frames by incorporating innovations like virtual fittings and virtual advice.

Hessel was a former venture capitalist who had worked in online opticals for more than a decade?first

with his own start-up, EyeBuyDirect, and then with Essilor after it acquired EyeBuyDirect. He had

become the CEO of Clearly when it was acquired by Essilor. Hessel brought a sense of renewed

engagement with the ECPs because, unlike the founder of Clearly, he recognized that ECPs played the

role of first responders and were therefore indispensable.

Within weeks of becoming CEO, Hessel took various strategic steps aimed at building bridges with ECPs.

He dispensed with price comparisons on the website and toned down its confrontational language. He

then moved the company's products slightly upmarket, focusing less on offering discounts. He also

invited members of the Opticians Association of Canada, a national industry association, to tour company

facilities and discuss opportunities for collaboration.

THE PROMISE OF OMNICHANNEL

Clearly opened its first physical store in March 2013 on Robson Street in downtown Vancouver. The

store opening contrasted with the predominant trend of brick-and-mortar companies moving online. The

company opened a second store in the Kitsilano neighbourhood of Vancouver in October of that year and a third, on Queen Street West in Toronto, in December. Together, the three stores represented investments

in omnichannel capabilities. The company saw the physical stores as a medium for conversations with

walk-in customers and as a way to demonstrate the ease with which optical products could be purchased

online. In addition to creating product awareness, the physical store was an opportunity to build the brand

and project an image of a digitally forward-looking company. An online attribute that fascinated many

customers was the ability to save their favourite frames to retrieve later.

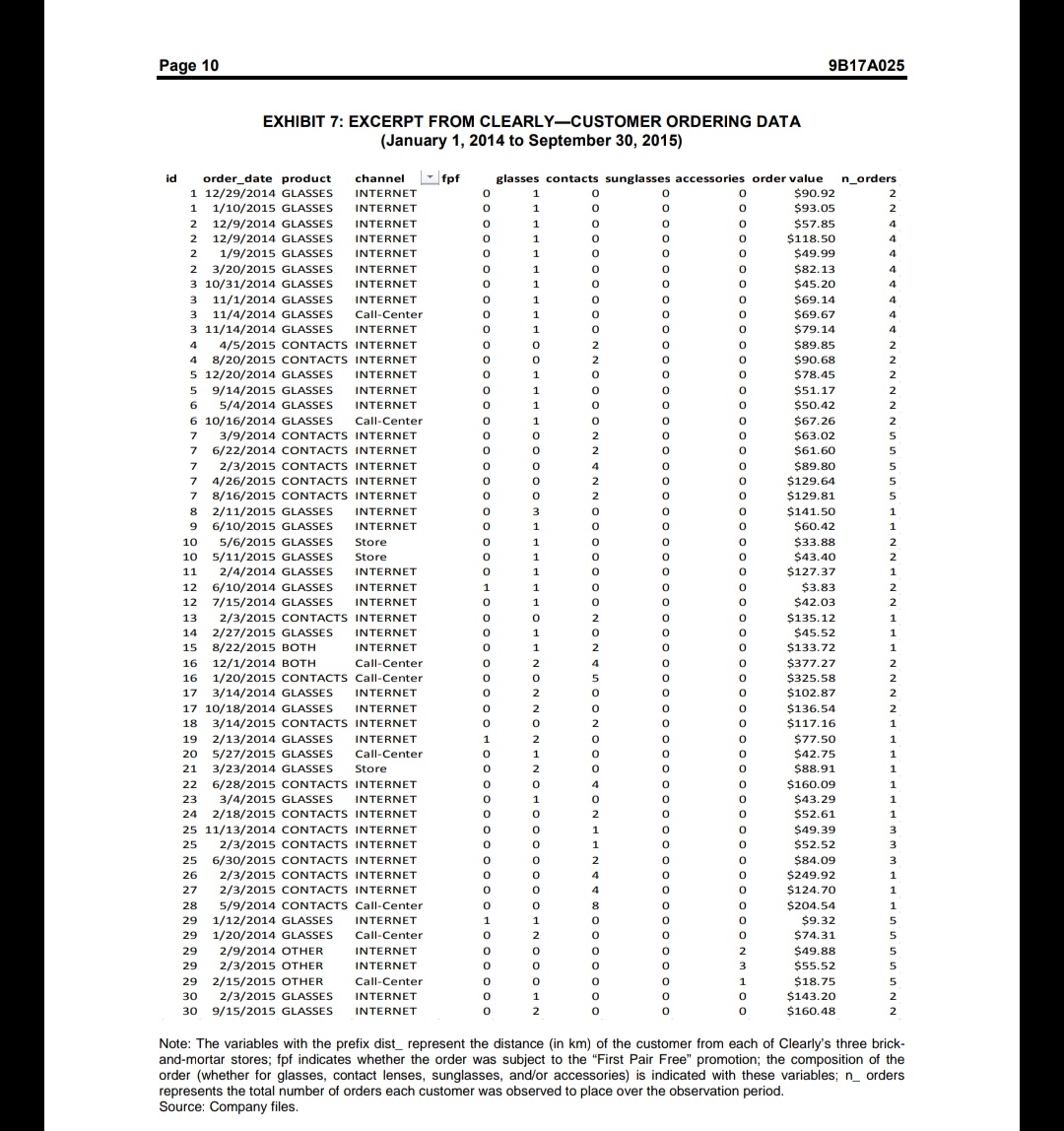

The company did not expect to make sales at the stores, but as it happened, sales at the stores were soon

complementing online sales (see Exhibits 6 and 7). Sixty per cent of the customers walking into Clearly's

stores were first-time visitors who were new to the company, whereas 40 per cent of its online customers

were new clients.

Clearly had set a target of achieving sales of $500 million by 2018,15 and doing so profitably. In spite of

being positioned as fashion accessories, eye wear products were witnessing online penetration of only 4

per cent. The company had launched a promotional offer called First Pair Free (FPF) for a limited period,

wherein customers paid only for shipping and handling while getting the frame, uncoated lenses, and a

case for their first order.

After 2014, Clearly sought to understand the demographic and psychographic attributes of its customers.

It commissioned Environics Research, a Toronto-based marketing and analytical services company, to

undertake an analysis of its existing customers in Canada, who numbered nearly 90,000 (excluding

Quebec). The analysis showed that Clearly's customers tended to be younger, urban singles and couples

with an average annual income of $85,000. They were university educated, held white-collar occupations,

and lived in apartments and condominiums in urban communities, which 55 per cent of them rented.

About 20 per cent had taken advantage of Clearly's FPF promotion, and 62 per cent of these customers

had made at least one subsequent purchase. A full 89 per cent of the company's customers were Internet

users, and 44 per cent were readers of daily newspapers. Clearly's customers were nearly two times more

likely than the general population to attend film festivals; about 1.5 times more likely to attend ballet,

opera, symphony, or music festivals; and about one-third more likely to visit nightclubs or bars, attend

food and wine shows, and see live theatre performances. They participated in sports such as marathon

running, racquet sports, snowboarding, billiards, inline skating, and adventure sports, and they tended to

use words like "eco-friendly products," "stylish," and "independent."

While eyewear products were positioned as fashion accessories, Clearly's online sales were penetrating

only 4 per cent of the available market. The slow rate of growth of the online optical market was

primarily due to two reasons: the historical battle with ECPs and the dynamics of omnichannel retailing.

Hessel had to find a way to address these two issues.

Keith Baker, the senior director of the company's global business and retail operations described the

challenge:

We are examining the way forward with physical retailing in terms of the prospects for customer

interaction. There are several possibilities. We could have showrooms where our latest collections

could be displayed for customers and, more particularly, for individual ECPs. We could have

innovation hubs where our product teams could interact with customers in a bid to identify unmet

optical needs and new design opportunities. We could have service centres where customers

could get their glasses cleaned, defects corrected, and fits adjusted by our associates. We could have kiosks where customers (even of competitor brands) could turn over used glasses for

recycling and get a credit on the purchase of a Clearly product.

Mending fences with ECPs

Although the messaging on the website had been toned down since Hessel's arrival, the tension between

Clearly and ECPs had remained high. An ongoing court case, College of Optometrists of Quebec v.

Coastal Contacts Inc., had progressed to the Court of Appeal.

Hessel saw that the task of getting ECPs on board could be done best by appealing to ECP's self-interest.

The company needed to focus on improving the performance metrics that an ECP would track regularly,

such as customer retention rate, average order value, and repeat purchase rate. He noted,

This is where I propose what I call a shared value model for the ECPs. It has three components.

First, it will link the business platform of an individual ECP with customers from Clearly's digital

platform, numbering millions worldwide. The linkage will extend the reach of ECPs beyond the

confines of their personal customer pool, personal domain, and personal time. Clearly will

provide its online customers with a choice of ECPs who are part of its platform. The referrals

from Clearly will enable ECPs to scale up their operations quickly and generate revenues.

Second, Clearly will also give ECPs access to its ongoing innovations in optical technology.

Optical frames have already evolved from being vision-correction accessories to fashion

accessories, and they will soon become data-carrying tools in their own right. Google Glass, for

example, is an indication of the shape of tools to come, although it has been unsuccessful. Third,

Clearly will provide turnkey solutions to individual ECPs. Powered by enabling technologies like

cloud computing and big data, the solutions will encompass everything that an ECP would

need?supply chain, customer communications, content management, billing, and payment

processing?to activate [its] own online optical store with a customized [application] that will be

quick, inexpensive, and easily scalable.

In calling for a truce, Hessel had to leverage the new identity of Clearly. It was no longer an e-commerce

company that had chosen optical products, as it had been in the beginning. As a division of Essilor, it was

now part of an optical company with extensive research, development, and supply-chain capabilities. It

was no longer an outsider but an insider with a mandate to make optical products affordable and more

widely available.

As he pondered Clearly's strategy for going forward, several questions requiring urgent resolution arose

in Hessel's mind: How did Clearly's multiple channels compare with respect to foot traffic and

subsequent conversion to sales? Were the three physical storefronts cannibalizing online sales, or were

they generating incremental sales? Were the customers using Clearly's multiple channels shopping more

frequently and making more purchases? Were the multiple channels more profitable than online only?

See exhibit in images.

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started