Question

Confidential information: Jonathan Cantor looked over DPVs standard template for a Series A term sheet. He would have to fill in several items, including the

Confidential information: Jonathan Cantor looked over DPVs standard template for a Series A term sheet. He would have to fill in several items, including the amount of capital and the pre-money valuation to be offered as well as the board composition. Otherwise, the templates boilerplate provisions were based on VC industry norms for a founder-friendly deal, so Cantor thought they should be acceptable to MuMat management. Those provisions included: Convertible preferred stock with a 1x non-participating liquidation preference, and no redemption rights Voting rights for Series A as if converted to common Antidilution protection (weighted average ratchet) Pro rata right to participate in future financings Founder common shares vest 25% on closing of DPVs investment, with the balance vesting linearly over 36 months. Unvested founder shares subject to buyback at fair market value1 Consent of a majority of preferred shares required for: dividends on common; preferred or common repurchase; loans to employees; merger or sale of substantially all assets; creation of a new security; incurring debt senior to Series A; change in principal business; investments in third parties; and major capital expenditures This was the first term sheet that Cantor had presented for a deal that he had sourced personally since he joined DPV nine months ago. MuMat was exactly the type of product that he had been hired to invest in: an innovative healthy-lifestyle brand, on the verge of exploding nationally. But Cantor knew that MuMat still faced many risks, and that he personally had a lot at stake, as the success of this investment could make or break his career at DPV.

Confidential information: Jonathan Cantor looked over DPVs standard template for a Series A term sheet. He would have to fill in several items, including the amount of capital and the pre-money valuation to be offered as well as the board composition. Otherwise, the templates boilerplate provisions were based on VC industry norms for a founder-friendly deal, so Cantor thought they should be acceptable to MuMat management. Those provisions included: Convertible preferred stock with a 1x non-participating liquidation preference, and no redemption rights Voting rights for Series A as if converted to common Antidilution protection (weighted average ratchet) Pro rata right to participate in future financings Founder common shares vest 25% on closing of DPVs investment, with the balance vesting linearly over 36 months. Unvested founder shares subject to buyback at fair market value1 Consent of a majority of preferred shares required for: dividends on common; preferred or common repurchase; loans to employees; merger or sale of substantially all assets; creation of a new security; incurring debt senior to Series A; change in principal business; investments in third parties; and major capital expenditures This was the first term sheet that Cantor had presented for a deal that he had sourced personally since he joined DPV nine months ago. MuMat was exactly the type of product that he had been hired to invest in: an innovative healthy-lifestyle brand, on the verge of exploding nationally. But Cantor knew that MuMat still faced many risks, and that he personally had a lot at stake, as the success of this investment could make or break his career at DPV.

First, Cantor had to decide how much capital to invest. According to MuMats projections, its cumulative capital requirement would peak at about $2.5 million (but it would be prudent to raise a bit more, $3 million, in case the projections were a bit off). The cost side of MuMats projections seemed sound, but there was considerable uncertainty about whether the startup would sustain its momentum and meet its revenue projections. Over the next 18 months, MuMat would have to fill inventory pipelines, invest in advertising, and staff up marketing and operationsall before knowing whether its brand was more than a West Coast fad. This risk capital would represent about half of the $3 million that MuMat required. The second half could be viewed as success capital. If MuMats business plan was successful through 2013, then any subsequent investments made during 2014 and beyond would be much less risky. This risk capital vs. success capital distinction suggested that DPV could stage its investment. DPV might offer, say, $1.5 million for the Series A, then follow with a Series B investment of another $1.5 million only if the company turned out to be successful. This staged approach would reduce the size of any potential losses for DPV if MuMat turned out not to be successful. The flip side was that if MuMat was successful, then MuMats valuation would increase at the Series Bi.e., its shares would become more expensive, perhaps as much as doubling in priceand so DPV would end up owning a smaller percentage of MuMat than if it had invested $3 million at once at the Series A. Would MuMat founders find one big round of $3 million appealing, or would they prefer to raise two smaller rounds? They almost would certainly recognize that with a single, bigger round instead of two smaller, staged rounds, they would be trading greater equity dilution (and so less ownership) in an upside scenario in exchange for having reserve capital on hand in a downside scenario. With a staged approach, a startup that had to raise money after missing key milestones faced a down round and big dilution if it could raise capital at all.

Cantor also needed to decide how to value MuMat at the Series A. He did some back-of-the- envelope valuation calculations using an approach often employed by his colleagues at DPV. The key

elements of the valuation were as follows: Consistent with its funds past performance and experience, DPV had a target IRR between 60% and 90% when investing in the Series A round of a startup run by founders with no prior entrepreneurial experience, as was the case of Maxwell and Taylor. MuMat had projected revenue of $50 million in 2015 (case Exhibit 6)of course, this projection assumed that the company was successful, as revenue would be essentially zero otherwise. If MuMat was acquired at the end of 2015 at a 1.4x revenue multiple, consistent with beverage industry transaction history (case Exhibit 7), then the total acquisition value would be $70 million. If DPV invested $3 million in the Series A in May 2012, it would need to receive between $3 1.63.5 million and $3 1.93.5 millioni.e., between $15.5 million and $28.4 millionat the end of 2015 (3.5 years later) to generate an IRR between 60% and 90%. This meant that DPV would need to own between 22.2% (=15.5/70) and 40.5% (=28.4/70) of MuMat. Given that MuMat did not expect to need to raise any more capital, this would imply a Series A post-money valuation between $7.4 (=3/0.405) million and $13.5 (=3/0.222) millionand thus a pre-money valuation between $4.4 million and $10.5 million. With two smaller, staged investments of $1.5 million, the exact pre-money valuation math

at the Series A was a bit more complex, but it yielded a roughly similar Series A pre- money valuation range of between $5.4 million and $11.4 million. However, in this case,

MuMat (B-2): Confidential for Cantor 813-150

3 DPV would initially only own between 11.6% (if it invested at an $11.4 million pre-money valuation, as 1.5/(11.4+1.5) = 11.6%) and 21.7% (if it invested at a $5.4 million pre-money valuation, as 1.5/(5.4+1.5) = 21.7%) of MuMat. DPV typically aimed to own at least a 20% stake when investing in a Series A rounda smaller stake didnt really warrant a partners time, as it would mean that DPV would have little influence on MuMats decisions and would benefit little from any value DPV added to MuMat with its advice and connections. So Cantor thought that if MuMat wanted a staged investment, the company would need to agree to a pre-money valuation in the low end of the $5.4 to $11.4 million range to ensure that the DPV partners would approve the deal. Cantor also wrestled with how to handle governance questions. In particular, he wondered whether to exclude Taylor from MuMats board. Cantor was sure that MuMats founders would object to this. Taylor was the products inventor and she had great instincts about building the brand. But the board could get her input without making Taylor a director, and having a large, unwieldy board had many downsides. When it was the sole investor in a Series A round, DPV had a strong preference for three board members, comprised of the founder/CEO, one DPV partner, and an outsider recommended by management and acceptable to DPV. Bigger boards could slow down decision making, especially when even numbers of directors led to deadlocked votes. And relationships could get messy whenever a senior manager was subordinate to the CEO in the context of day-to-day management, but a peer on the companys board. Cantor expected friction over other term sheet issues. For example, many first-time founders were uncomfortable with the idea that their equity should be subject to vesting, even though this was standard practice with venture capital rounds. As he entered figures into the term sheet template, Cantor wondered whether he faced competition from other investors for this deal. When he had asked Maxwell whether she was talking to other VCs, she had responded cryptically, We are looking at a range of funding options.

Information is regarding the Case study

MuMate

By: Thomas R. Eisenmann, Alex Godden

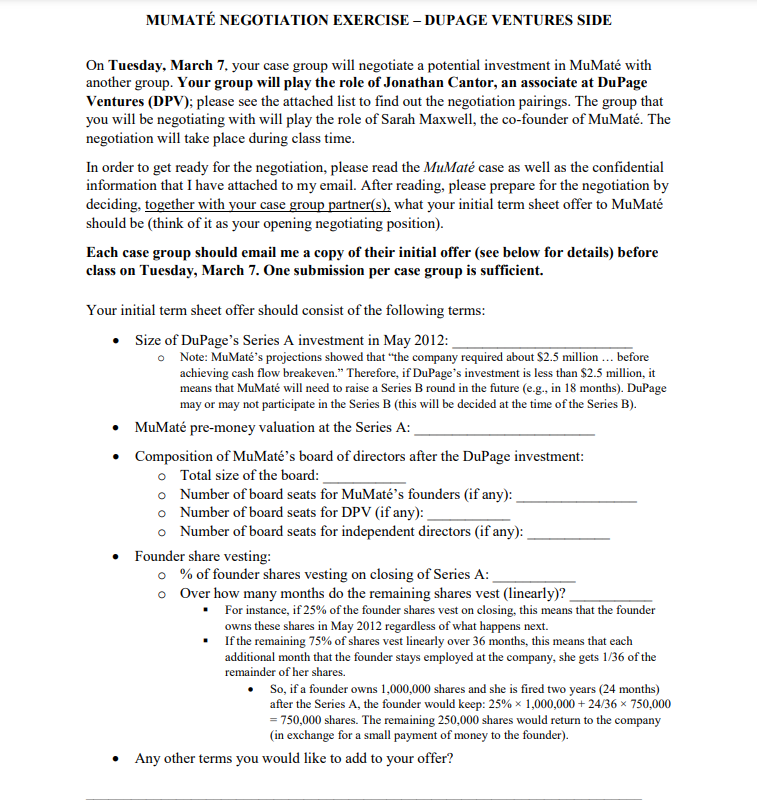

MUMAT NEGOTIATION EXERCISE - DUPAGE VENTURES SIDE On Tuesday, March 7, your case group will negotiate a potential investment in MuMat with another group. Your group will play the role of Jonathan Cantor, an associate at DuPage Ventures (DPV); please see the attached list to find out the negotiation pairings. The group that you will be negotiating with will play the role of Sarah Maxwell, the co-founder of MuMat. The negotiation will take place during class time. In order to get ready for the negotiation, please read the MuMat case as well as the confidential information that I have attached to my email. After reading, please prepare for the negotiation by deciding, together with your case group partner(s), what your initial term sheet offer to MuMat should be (think of it as your opening negotiating position). Each case group should email me a copy of their initial offer (see below for details) before class on Tuesday, March 7. One submission per case group is sufficient. Your initial term sheet offer should consist of the following terms: - Size of DuPage's Series A investment in May 2012: - Note: MuMat's projections showed that "the company required about $2.5 million ... before achieving cash flow breakeven." Therefore, if DuPage's investment is less than $2.5 million, it means that MuMat will need to raise a Series B round in the future (e.g., in 18 months). DuPage may or may not participate in the Series B (this will be decided at the time of the Series B). - MuMat pre-money valuation at the Series A: - Composition of MuMat's board of directors after the DuPage investment: Total size of the board: - Number of board seats for MuMat's founders (if any): - Number of board seats for DPV (if any): Number of board seats for independent directors (if any): - Founder share vesting: - % of founder shares vesting on closing of Series A: - Over how many months do the remaining shares vest (linearly)? - For instance, if 25% of the founder shares vest on closing, this means that the founder owns these shares in May 2012 regardless of what happens next. - If the remaining 75% of shares vest linearly over 36 months, this means that each additional month that the founder stays employed at the company, she gets 1/36 of the remainder of her shares. - So, if a founder owns 1,000,000 shares and she is fired two years ( 24 months) after the Series A, the founder would keep: 25%1,000,000+24/36750,000 =750,000 shares. The remaining 250,000 shares would return to the company (in exchange for a small payment of money to the founder). - Any other terms you would like to add to your offerStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started