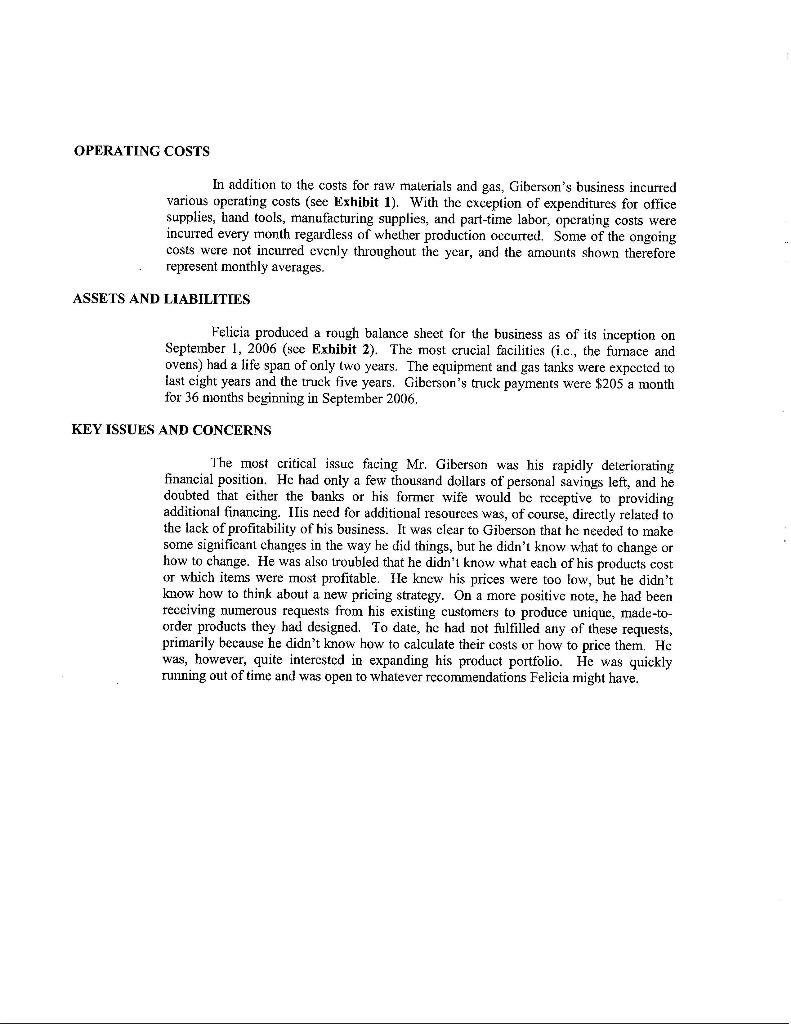

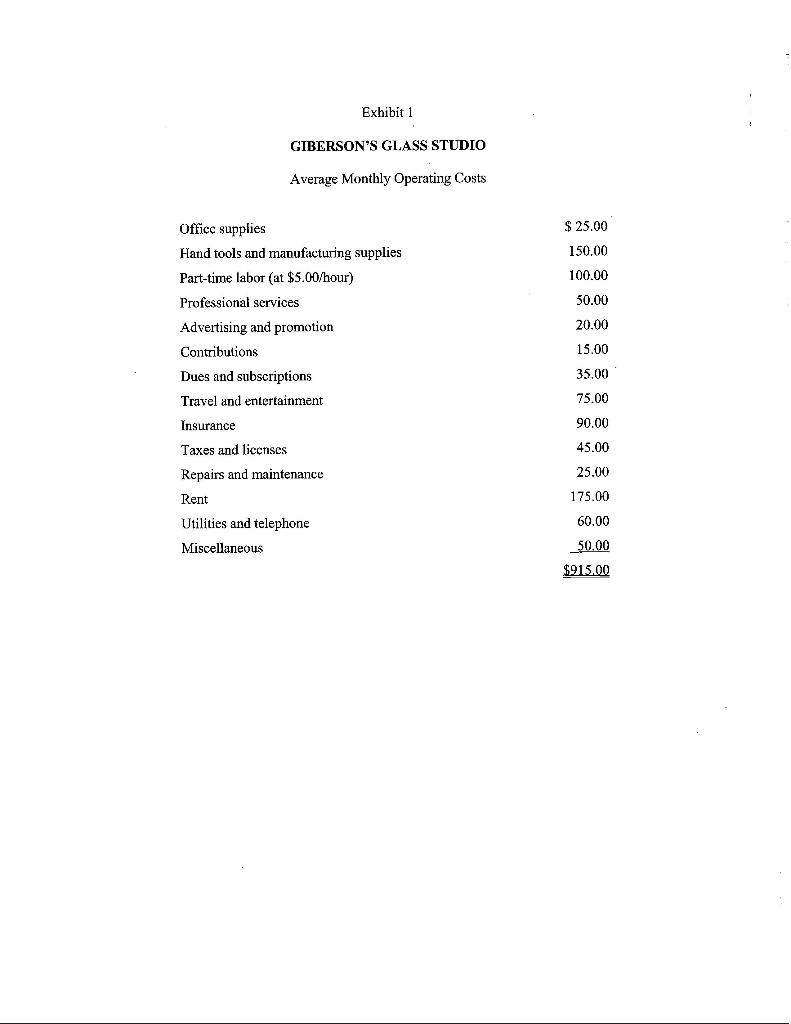

Determine the expected annual revenue, operating costs, and the annual income or loss for Mr. Giberson.

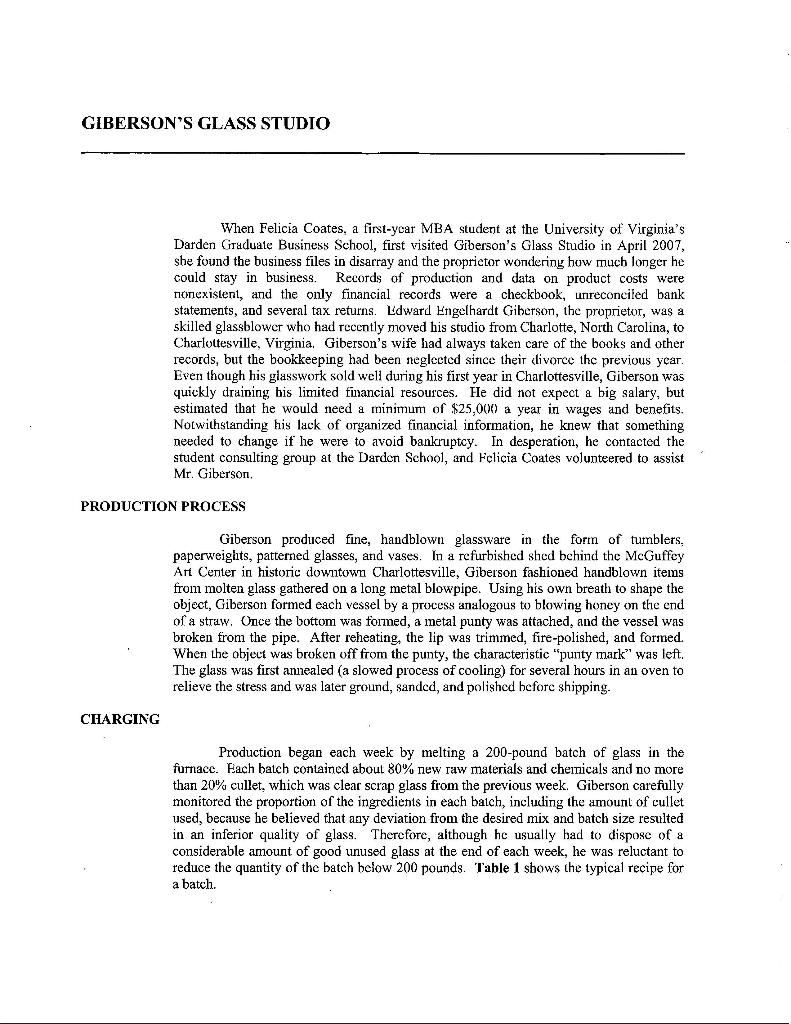

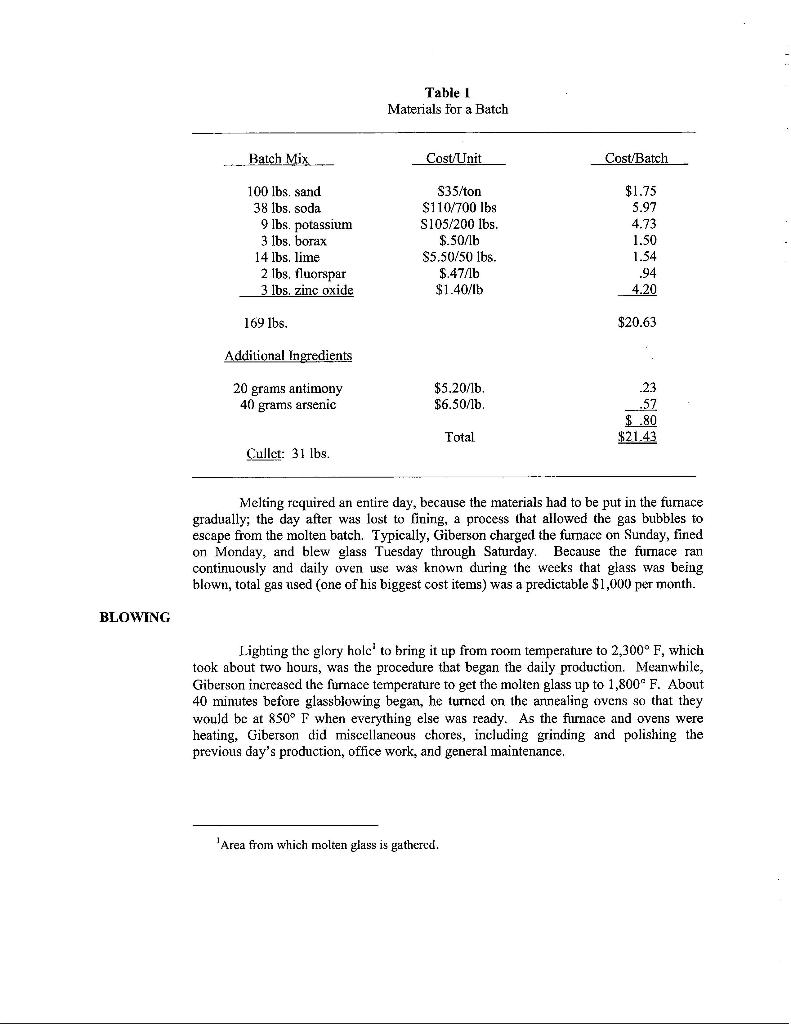

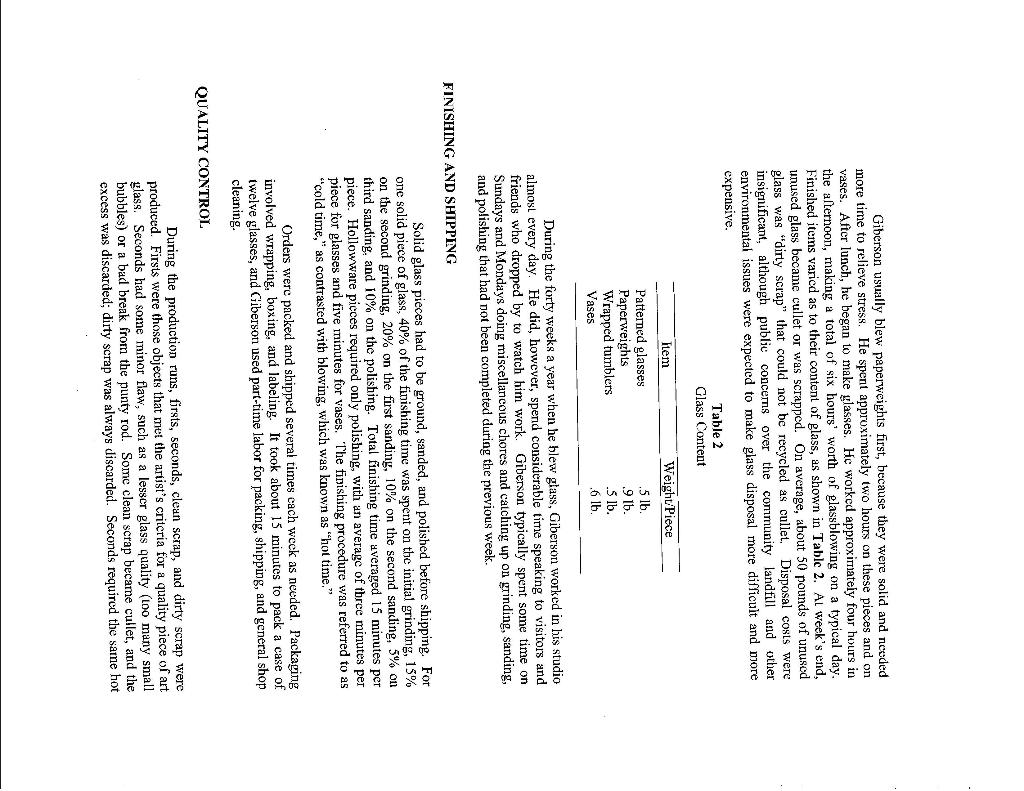

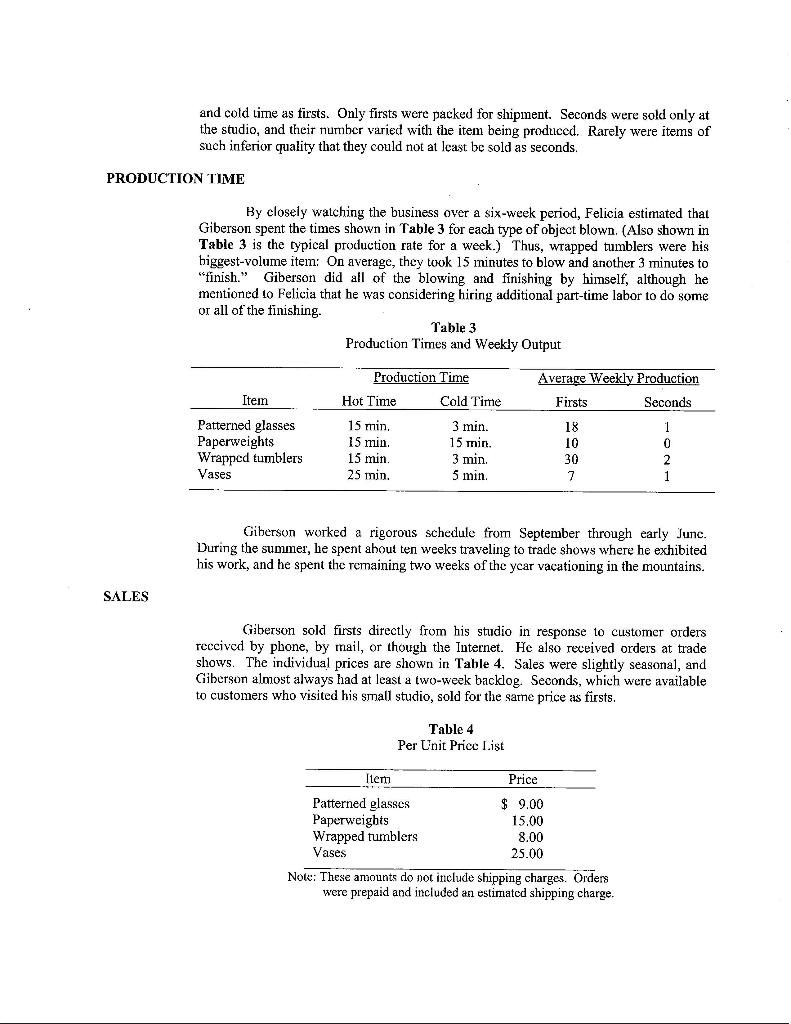

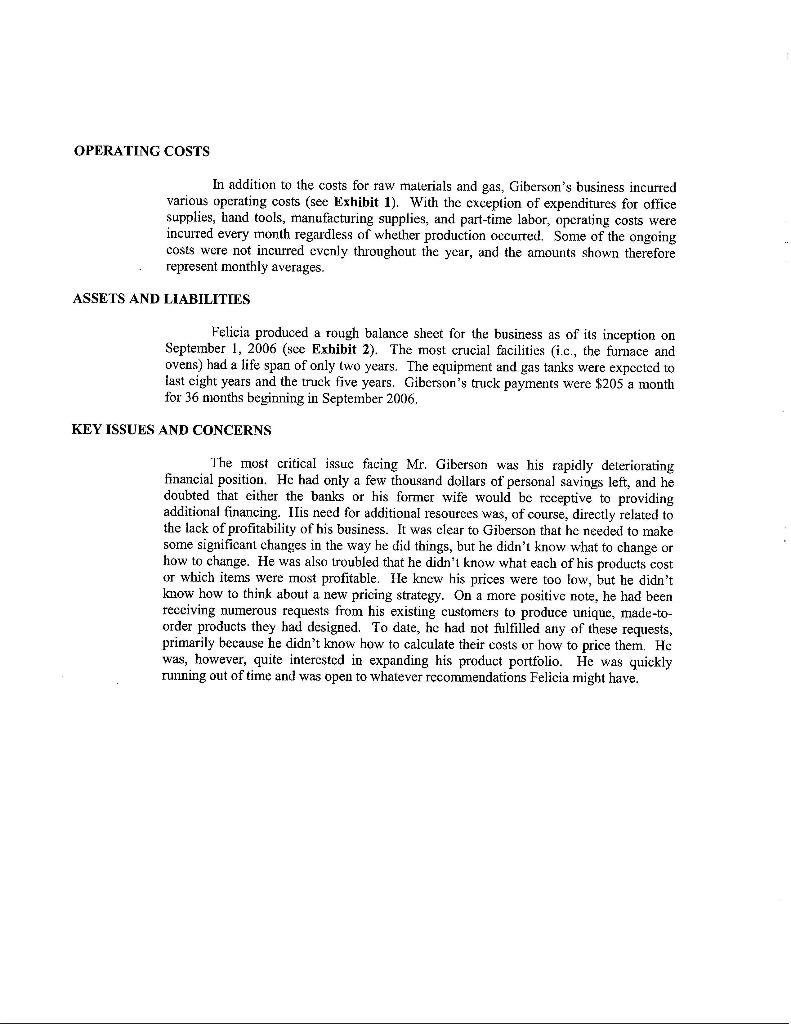

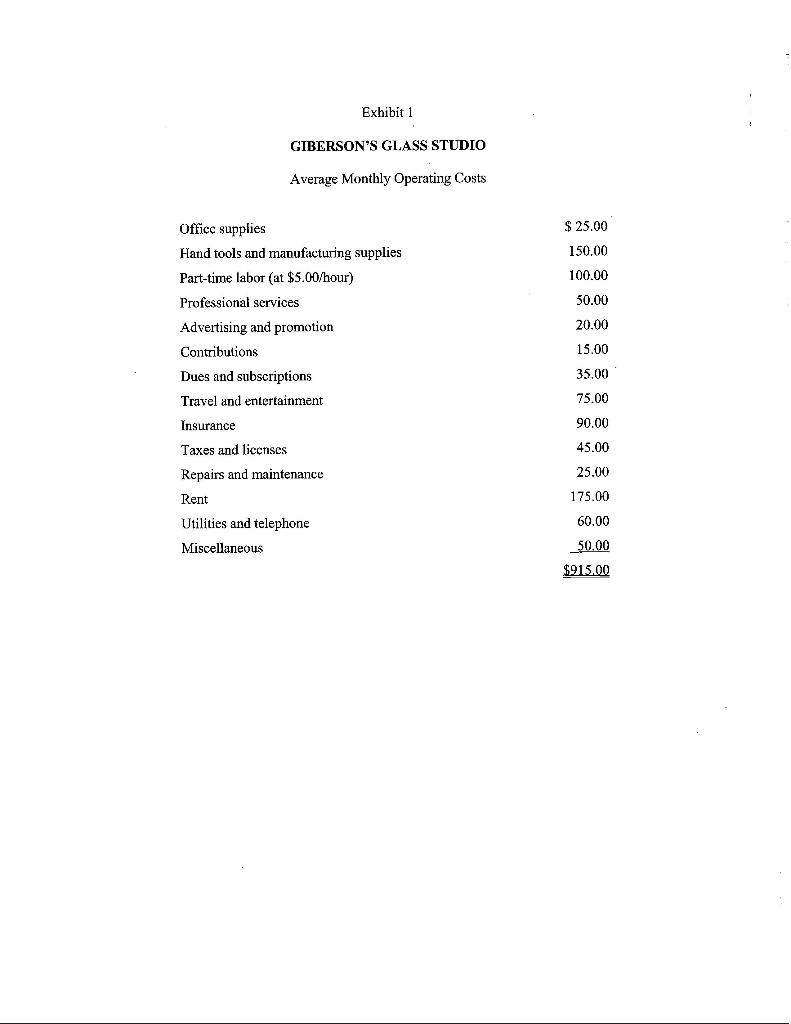

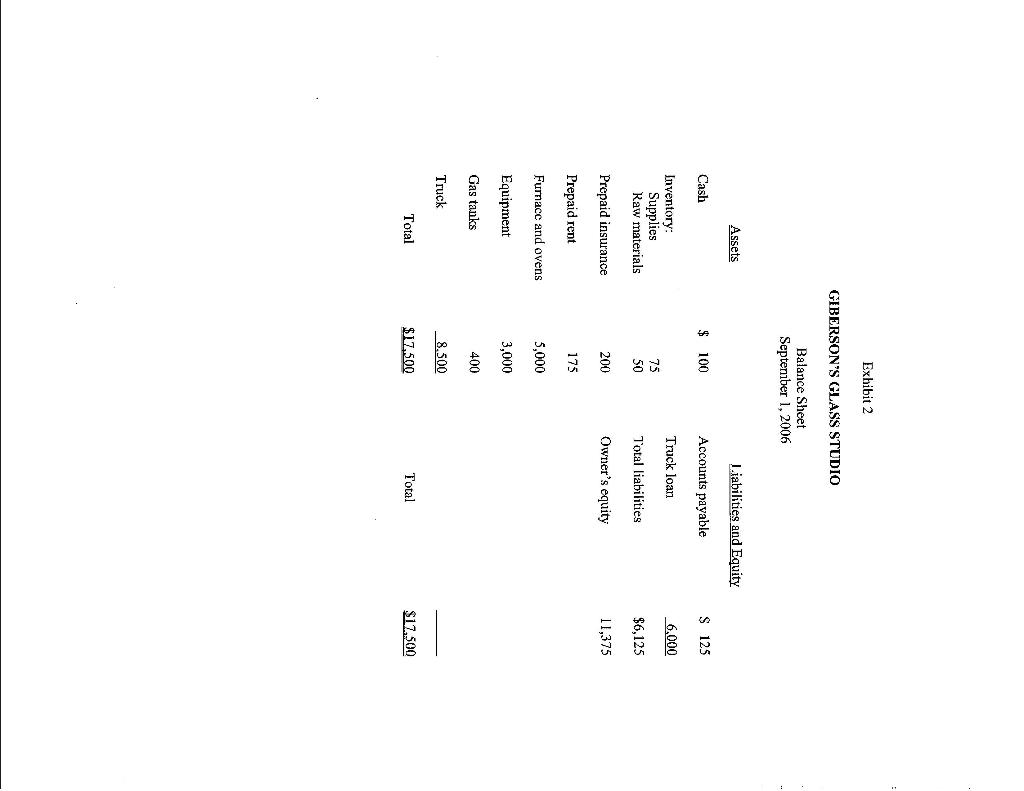

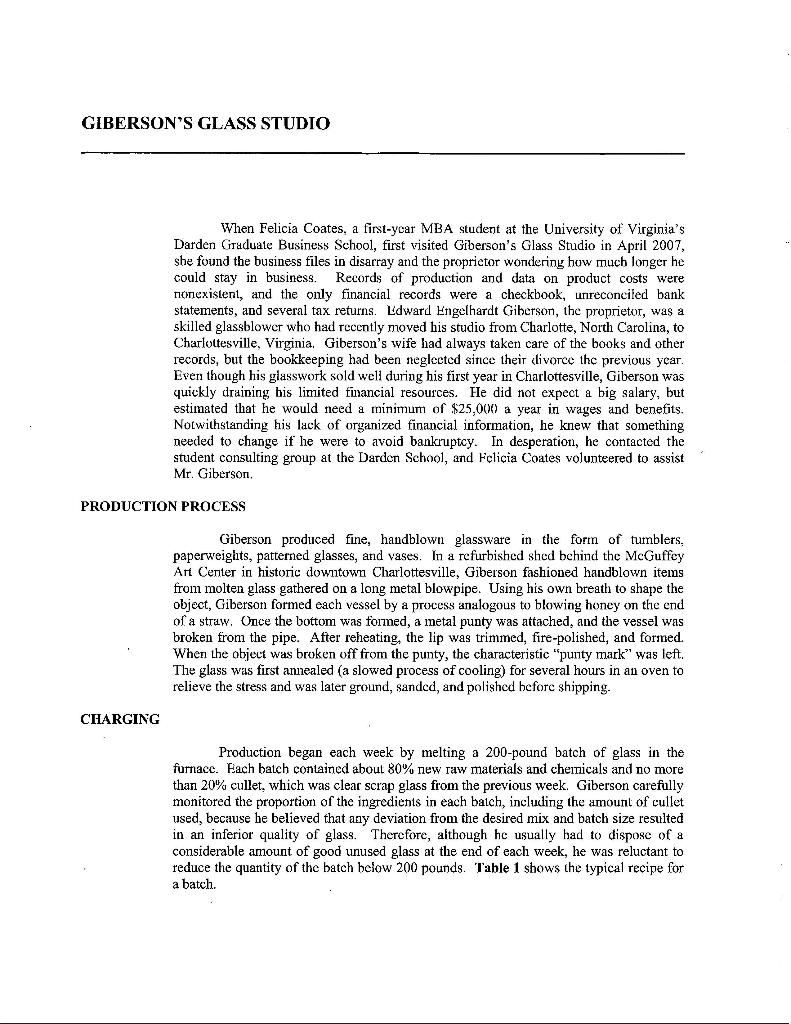

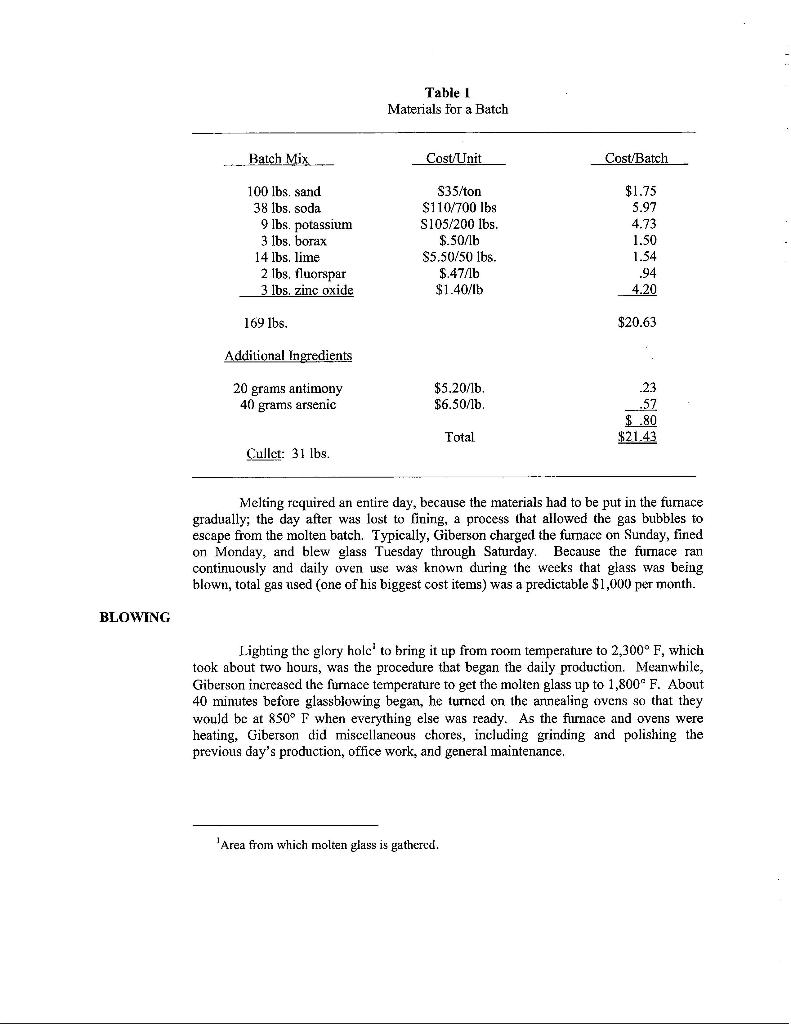

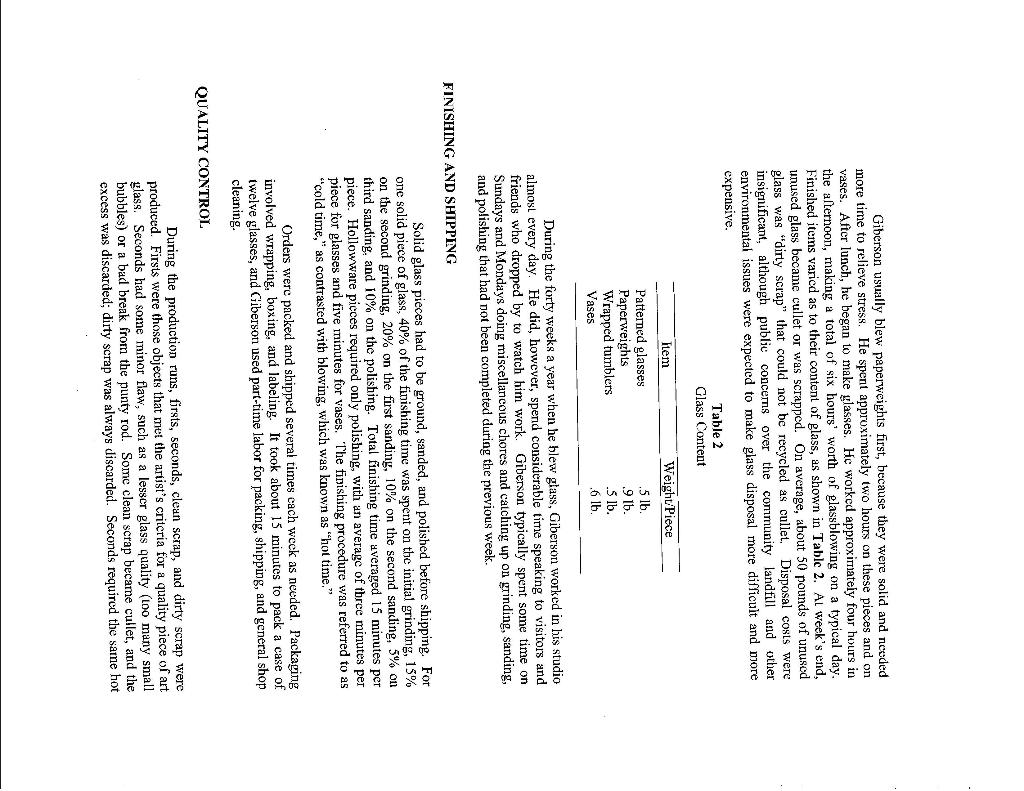

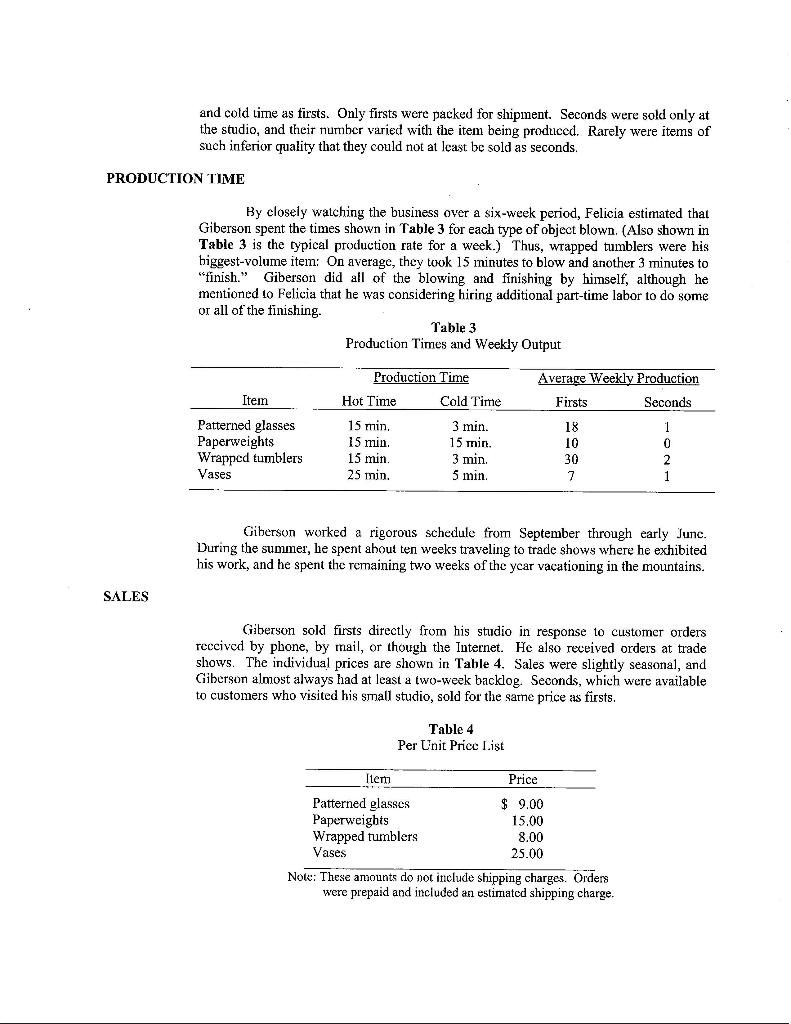

GIBERSON'S GLASS STUDIO When Felicia Coates, a first-year MBA student at the University of Virginia's Darden Graduate Business School, first visited Giberson's Glass Studio in April 2007, she found the business files in disarray and the proprietor wondering how much longer he could stay in business. Records of production and data on product costs were nonexistent, and the only financial records were a checkbook, unreconciled bank statements, and several tax returns. Edward Engelhardt Giberson, the proprietor, was a skilled glassblower who had recently moved his studio from Charlotte, North Carolina, to Charlottesville, Virginia. Giberson's wife had always taken care of the books and other records, but the bookkeeping had been neglected since their livorce the previous year. Even though his glasswork sold well during his first year in Charlottesville, Giberson was quickly draining bis limited financial resources. He did not expect a big salary, but estimated that he would need a minimum of $25,000 a year in wages and benefits. Notwithstanding his lack of organized financial information, he knew that something needed to change if he were to avoid bankruptcy. In desperation, he contacted the student consulting group at the Darden School, and Felicia Coates volunteered to assist Mr. Giberson PRODUCTION PROCESS Giberson produced fine, handblown glassware in the form of tumblers, paperweights, patterned glasses, and vases. In a refurbished shed behind the McGuffey Art Center in historic downtown Charlottesville, Giberson fashioned handblown items from molten glass gathered on a long metal blowpipe. Using his own breath to shape the object, Giberson formed each vessel by a process analogous to blowing honey on the end of a straw. Once the bottom was formed, a metal punty was attached, and the vessel was broken from the pipe. After reheating, the lip was trimmed, fire-polished, and formed. When the object was broken off from the punty, the characteristic "punty mark" was left. The glass was first annealed (a slowed process of cooling) for several hours in an oven to relieve the stress and was later ground, sanded, and polished hefore shipping. CHARGING Production began each week by melting a 200-pound batch of glass in the furnace. Each batch contained about 80% new raw materials and cheinicals and no more than 20% cullet, which was clear scrap glass from the previous week. Giberson carefully monitored the proportion of the ingredients in each batch, including the amount of cullet used, because he believed that any deviation from the desired mix and batch size resulted in an inferior quality of glass. Therefore, although he usually had to dispose of a considerable amount of good unused glass at the end of each week, he was reluctant to reduce the quantity of the batch below 200 pounds. Table 1 shows the typical recipe for a batch. Table 1 Materials for a Batch Batch Mix Cost/Unit Cost/Batch 100 lbs. sand 38 lbs, soda 9 lbs, potassium 3 lbs. borax 14 lbs. lime 2 lbs, fluorspar 3 lbs, zinc oxide S35/ton $110/700 lbs S105/200 lbs. $.50/1b $5.50/50 lbs. $.47/16 $1.40/1b $1.75 5.97 4.73 1.50 1.54 .94 4.20 169 lbs. $20.63 Additional Ingredients 20 grams antimony $5.20/15 $6.50/1b. 40 grams arsenic 23 57 $.80 $21.43 Total Cullet: 31 lbs. Melting required an entire day, because the materials had to be put in the fumace gradually; the day after was lost to fining, a process that allowed the gas bubbles to escape from the molten batch. Typically, Giberson charged the furnace on Sunday, fined on Monday, and blew glass Tuesday through Saturday. Because the furnace rau continuously and daily oven use was known during the weeks that glass was being blown, total gas used (one of his biggest cost items) was a predictable $1,000 per month. BLOWING Lighting the glory hole to bring it up from room temperature to 2,300 F, which took about two hours, was the procedure that began the daily production. Meanwhile, Giberson increased the furnace temperature to get the molten glass up to 1,800F. About 40 minutes before glassblowing began, he turned on the annealing ovens so that they would be at 850 T when everything else was ready. As the furnace and ovens were heating, Giberson did miscellaneous chores, including grinding and polishing the previous day's production, office work, and general maintenance. 'Area from which molten glass is gathered. Giberson usually blew paperweights first, because they were solid and needed more time to relieve stress. He spent approximately two hours on these pieces and on vases. After lunch, he began to make glasses. He worked approximately four hours in the afternoon, making a total of six hours' worth of glassblowing on a typical day. Finished items varied as to their content of glass, as shown in Table 2. Al week's end, unused glass became cullet or was scrapped. On average, about 50 pounds of unused glass was "dirty scrap" that could not be recycled as cullet. Disposal costs were insignificant, although public concerns over the community landfill and other environmental issues were expected to make glass disposal more difficult and more expensive. Table 2 Glass Content Item Weight/Piece Patterned glasses Paperweights Wrapped tumblers Vases 5 lb 9 lb. 5 lb. .6 lb. During the forty weeks a year when he blew glass, Giberson worked in his studio almost every day. He did, however, spend considerable time speaking to visitors and friends who dropped by to watch him work. Giberson typically spent some time on Sundays and Mondays doing miscellancous chores and catching up on grinding, sanding, and polishing that had not been completed during the previous week. FINISHING AND SHIPPING Solid glass pieces had to be ground, sanded, and polished before shipping. For one solid piece of glass, 40% of the finishing time was spent on the initial grinding, 15% on the second grinding, 20% on the first sanding, 10% on the second sancing, 5% on third sanding, and 10% on the polishing. Total finishing time averaged 15 minutes per piece. Hollowware picces required only polishing, with an average of three minutes per piece for glasses and five minutes for vases. The finishing procedure was referred to a "cold time," as contrasted with blowing, which was known as "hot time." Orders were packed and shipped several times cach week as needed. Packaging involved wrapping, boxing, and labeling. It took about 15 minutes to pack a case of twelve glasses, and Giberson used part-time labor for packing, shipping, and general shop cleaning. QUALITY CONTROL During the production runs, firsts, seconds, clean scrap, and dirty scrap were produced. Firsts were those objects that met the artist's criteria for a quality piece of art glass. Seconds had some minor flaw, such as a lesser glass quality (L00 many small bubbles) or a bad break from the punty rod. Some clean scrap became cullet, and the excess was discarded; dirty scrap was always discarded. Seconds required the same hot and cold time as tirsts. Only firsts were packed for shipment. Seconds were sold only at the studio, and their number varied with the item being produced. Rarely were items of such inferior quality that they could not at least be sold as seconds PRODUCTION TIME By closely watching the business over a six-week period, Felicia estimated that Giberson spent the times shown in Table 3 for each type of object blown. (Also shown in Table 3 is the typical production rate for a week.) Thus, wrapped tumblers were his biggest-volume iten: On average, they took 15 minutes to blow and another 3 minutes to "finish." Giberson did all of the blowing and finishing by himself, although he mentioned to Felicia that he was considering hiring additional part-time labor to do some or all of the finishing. Table 3 Production Times and Weekly Output Average Weekly Production Firsts Seconds Item Patterned glasses Paperweights Wrapped tumblers Vases Production Time Hot Time Cold Time 15 min. 3 min. 15 min. 15 min. 15 min 3 min. 25 min. 5 min 18 10 30 7 1 0 2 Giberson worked a rigorous schedule from September through early Junc. During the summer, he spent about ten weeks traveling to trade shows where he exhibited his work, and he spent the remaining two weeks of the year vacationing in the mountains. SALES Giberson sold firsts directly from his studio in response to customer orders received by pbone, by mail, or though the Internet. He also received orders at trade shows. The individual prices are shown in Table 4. Sales were slightly seasonal, and Giberson almost always had at least a two-week backlog. Seconds, which were available to customers who visited his small studio, sold for the sarne price as firsts. Table 4 Per Unit Price List Item Price 8.00 Patterned glasses $ 9.00 Paperweights 15.00 Wrapped tumblers Vases 25.00 Note: These amounts do not include shipping charges. Orders were prepaid and included an estimated shipping charge. OPERATING COSTS In addition to the costs for raw materials and gas, Giberson's business incurred various operating costs (see Exhibit 1). With the exception of expenditures for office supplies, hand tools, manufacturing supplies, and part-time labor, operating costs were incurred every month regardless of whether production occurred. Some of the ongoing costs were not incurred evenly throughout the year, and the amounts shown therefore represent monthly averages. ASSETS AND LIABILITIES Felicia produced a rough balance sheet for the business as of its inception on September 1, 2006 (sce Exhibit 2). The most crucial facilities (i.c., the furnace and ovens) had a life span of only two years. The equipment and gas tanks were expected to last eight years and the truck five years. Giberson's truck payments were $205 a month for 36 months beginning in September 2006. KEY ISSUES AND CONCERNS to change or The most critic issue facing Mr. Giberson was his rapidly deteriorating financial position. He had only a few thousand dollars of personal savings left, and he doubted that either the banks or his former wife would be receptive to providing additional financing. Ilis need for additional resources was, of course, directly related to the lack of profitability of his business. It was clear to Giberson that he needed to make some significant changes in the way he did things, but he didn't know what to how to change. He was also troubled that he didn't know what each of his products cost or which items were most profitable. Ile knew his prices were too low, but he didn't know how to think about a new pricing strategy. On a more positive note, he had been recciving numerous requests from his existing customers to produce unique, made-to- order products they had designed. To date, he had not fulfilled any of these requests, primarily because he didn't know how to calculate their costs or how to price them. He was, however, quite interested in expanding his product portfolio. He was quickly running out of time and was open to whatever recommendations Felicia might have. Exhibit 1 GIBERSON'S GLASS STUDIO Average Monthly Operating Costs $ 25.00 150.00 100.00 50.00 20.00 15.00 Office supplies Hand tools and manufacturing supplies Part-time labor (at $5.00/hour) Professional services Advertising and promotion Contributions Dues and subscriptions Travel and entertainment Insurance Taxes and licenses Repairs and maintenance Rent 35.00 75.00 90.00 45.00 25.00 175.00 60.00 Utilities and telephone Miscellaneous _$0.00 $915.00 Exbibit 2 GIBERSON'S GLASS STUDIO Balance Sheet Septeniber 1, 2006 Assets Liabilities and Equity Cash $ 100 Accounts payable $ 125 Truck loan 6,000 Inventory Supplies Kaw materials 75 50 Total liabilities $6,125 Prepaid insurance 200 Owner's equity 11,375 Prepaid rent 175 Fumace and ovens 5,000 Equipment 3,000 Gas tanks 400 Truck 8.500 Total $17.500 Total $17.500 GIBERSON'S GLASS STUDIO When Felicia Coates, a first-year MBA student at the University of Virginia's Darden Graduate Business School, first visited Giberson's Glass Studio in April 2007, she found the business files in disarray and the proprietor wondering how much longer he could stay in business. Records of production and data on product costs were nonexistent, and the only financial records were a checkbook, unreconciled bank statements, and several tax returns. Edward Engelhardt Giberson, the proprietor, was a skilled glassblower who had recently moved his studio from Charlotte, North Carolina, to Charlottesville, Virginia. Giberson's wife had always taken care of the books and other records, but the bookkeeping had been neglected since their livorce the previous year. Even though his glasswork sold well during his first year in Charlottesville, Giberson was quickly draining bis limited financial resources. He did not expect a big salary, but estimated that he would need a minimum of $25,000 a year in wages and benefits. Notwithstanding his lack of organized financial information, he knew that something needed to change if he were to avoid bankruptcy. In desperation, he contacted the student consulting group at the Darden School, and Felicia Coates volunteered to assist Mr. Giberson PRODUCTION PROCESS Giberson produced fine, handblown glassware in the form of tumblers, paperweights, patterned glasses, and vases. In a refurbished shed behind the McGuffey Art Center in historic downtown Charlottesville, Giberson fashioned handblown items from molten glass gathered on a long metal blowpipe. Using his own breath to shape the object, Giberson formed each vessel by a process analogous to blowing honey on the end of a straw. Once the bottom was formed, a metal punty was attached, and the vessel was broken from the pipe. After reheating, the lip was trimmed, fire-polished, and formed. When the object was broken off from the punty, the characteristic "punty mark" was left. The glass was first annealed (a slowed process of cooling) for several hours in an oven to relieve the stress and was later ground, sanded, and polished hefore shipping. CHARGING Production began each week by melting a 200-pound batch of glass in the furnace. Each batch contained about 80% new raw materials and cheinicals and no more than 20% cullet, which was clear scrap glass from the previous week. Giberson carefully monitored the proportion of the ingredients in each batch, including the amount of cullet used, because he believed that any deviation from the desired mix and batch size resulted in an inferior quality of glass. Therefore, although he usually had to dispose of a considerable amount of good unused glass at the end of each week, he was reluctant to reduce the quantity of the batch below 200 pounds. Table 1 shows the typical recipe for a batch. Table 1 Materials for a Batch Batch Mix Cost/Unit Cost/Batch 100 lbs. sand 38 lbs, soda 9 lbs, potassium 3 lbs. borax 14 lbs. lime 2 lbs, fluorspar 3 lbs, zinc oxide S35/ton $110/700 lbs S105/200 lbs. $.50/1b $5.50/50 lbs. $.47/16 $1.40/1b $1.75 5.97 4.73 1.50 1.54 .94 4.20 169 lbs. $20.63 Additional Ingredients 20 grams antimony $5.20/15 $6.50/1b. 40 grams arsenic 23 57 $.80 $21.43 Total Cullet: 31 lbs. Melting required an entire day, because the materials had to be put in the fumace gradually; the day after was lost to fining, a process that allowed the gas bubbles to escape from the molten batch. Typically, Giberson charged the furnace on Sunday, fined on Monday, and blew glass Tuesday through Saturday. Because the furnace rau continuously and daily oven use was known during the weeks that glass was being blown, total gas used (one of his biggest cost items) was a predictable $1,000 per month. BLOWING Lighting the glory hole to bring it up from room temperature to 2,300 F, which took about two hours, was the procedure that began the daily production. Meanwhile, Giberson increased the furnace temperature to get the molten glass up to 1,800F. About 40 minutes before glassblowing began, he turned on the annealing ovens so that they would be at 850 T when everything else was ready. As the furnace and ovens were heating, Giberson did miscellaneous chores, including grinding and polishing the previous day's production, office work, and general maintenance. 'Area from which molten glass is gathered. Giberson usually blew paperweights first, because they were solid and needed more time to relieve stress. He spent approximately two hours on these pieces and on vases. After lunch, he began to make glasses. He worked approximately four hours in the afternoon, making a total of six hours' worth of glassblowing on a typical day. Finished items varied as to their content of glass, as shown in Table 2. Al week's end, unused glass became cullet or was scrapped. On average, about 50 pounds of unused glass was "dirty scrap" that could not be recycled as cullet. Disposal costs were insignificant, although public concerns over the community landfill and other environmental issues were expected to make glass disposal more difficult and more expensive. Table 2 Glass Content Item Weight/Piece Patterned glasses Paperweights Wrapped tumblers Vases 5 lb 9 lb. 5 lb. .6 lb. During the forty weeks a year when he blew glass, Giberson worked in his studio almost every day. He did, however, spend considerable time speaking to visitors and friends who dropped by to watch him work. Giberson typically spent some time on Sundays and Mondays doing miscellancous chores and catching up on grinding, sanding, and polishing that had not been completed during the previous week. FINISHING AND SHIPPING Solid glass pieces had to be ground, sanded, and polished before shipping. For one solid piece of glass, 40% of the finishing time was spent on the initial grinding, 15% on the second grinding, 20% on the first sanding, 10% on the second sancing, 5% on third sanding, and 10% on the polishing. Total finishing time averaged 15 minutes per piece. Hollowware picces required only polishing, with an average of three minutes per piece for glasses and five minutes for vases. The finishing procedure was referred to a "cold time," as contrasted with blowing, which was known as "hot time." Orders were packed and shipped several times cach week as needed. Packaging involved wrapping, boxing, and labeling. It took about 15 minutes to pack a case of twelve glasses, and Giberson used part-time labor for packing, shipping, and general shop cleaning. QUALITY CONTROL During the production runs, firsts, seconds, clean scrap, and dirty scrap were produced. Firsts were those objects that met the artist's criteria for a quality piece of art glass. Seconds had some minor flaw, such as a lesser glass quality (L00 many small bubbles) or a bad break from the punty rod. Some clean scrap became cullet, and the excess was discarded; dirty scrap was always discarded. Seconds required the same hot and cold time as tirsts. Only firsts were packed for shipment. Seconds were sold only at the studio, and their number varied with the item being produced. Rarely were items of such inferior quality that they could not at least be sold as seconds PRODUCTION TIME By closely watching the business over a six-week period, Felicia estimated that Giberson spent the times shown in Table 3 for each type of object blown. (Also shown in Table 3 is the typical production rate for a week.) Thus, wrapped tumblers were his biggest-volume iten: On average, they took 15 minutes to blow and another 3 minutes to "finish." Giberson did all of the blowing and finishing by himself, although he mentioned to Felicia that he was considering hiring additional part-time labor to do some or all of the finishing. Table 3 Production Times and Weekly Output Average Weekly Production Firsts Seconds Item Patterned glasses Paperweights Wrapped tumblers Vases Production Time Hot Time Cold Time 15 min. 3 min. 15 min. 15 min. 15 min 3 min. 25 min. 5 min 18 10 30 7 1 0 2 Giberson worked a rigorous schedule from September through early Junc. During the summer, he spent about ten weeks traveling to trade shows where he exhibited his work, and he spent the remaining two weeks of the year vacationing in the mountains. SALES Giberson sold firsts directly from his studio in response to customer orders received by pbone, by mail, or though the Internet. He also received orders at trade shows. The individual prices are shown in Table 4. Sales were slightly seasonal, and Giberson almost always had at least a two-week backlog. Seconds, which were available to customers who visited his small studio, sold for the sarne price as firsts. Table 4 Per Unit Price List Item Price 8.00 Patterned glasses $ 9.00 Paperweights 15.00 Wrapped tumblers Vases 25.00 Note: These amounts do not include shipping charges. Orders were prepaid and included an estimated shipping charge. OPERATING COSTS In addition to the costs for raw materials and gas, Giberson's business incurred various operating costs (see Exhibit 1). With the exception of expenditures for office supplies, hand tools, manufacturing supplies, and part-time labor, operating costs were incurred every month regardless of whether production occurred. Some of the ongoing costs were not incurred evenly throughout the year, and the amounts shown therefore represent monthly averages. ASSETS AND LIABILITIES Felicia produced a rough balance sheet for the business as of its inception on September 1, 2006 (sce Exhibit 2). The most crucial facilities (i.c., the furnace and ovens) had a life span of only two years. The equipment and gas tanks were expected to last eight years and the truck five years. Giberson's truck payments were $205 a month for 36 months beginning in September 2006. KEY ISSUES AND CONCERNS to change or The most critic issue facing Mr. Giberson was his rapidly deteriorating financial position. He had only a few thousand dollars of personal savings left, and he doubted that either the banks or his former wife would be receptive to providing additional financing. Ilis need for additional resources was, of course, directly related to the lack of profitability of his business. It was clear to Giberson that he needed to make some significant changes in the way he did things, but he didn't know what to how to change. He was also troubled that he didn't know what each of his products cost or which items were most profitable. Ile knew his prices were too low, but he didn't know how to think about a new pricing strategy. On a more positive note, he had been recciving numerous requests from his existing customers to produce unique, made-to- order products they had designed. To date, he had not fulfilled any of these requests, primarily because he didn't know how to calculate their costs or how to price them. He was, however, quite interested in expanding his product portfolio. He was quickly running out of time and was open to whatever recommendations Felicia might have. Exhibit 1 GIBERSON'S GLASS STUDIO Average Monthly Operating Costs $ 25.00 150.00 100.00 50.00 20.00 15.00 Office supplies Hand tools and manufacturing supplies Part-time labor (at $5.00/hour) Professional services Advertising and promotion Contributions Dues and subscriptions Travel and entertainment Insurance Taxes and licenses Repairs and maintenance Rent 35.00 75.00 90.00 45.00 25.00 175.00 60.00 Utilities and telephone Miscellaneous _$0.00 $915.00 Exbibit 2 GIBERSON'S GLASS STUDIO Balance Sheet Septeniber 1, 2006 Assets Liabilities and Equity Cash $ 100 Accounts payable $ 125 Truck loan 6,000 Inventory Supplies Kaw materials 75 50 Total liabilities $6,125 Prepaid insurance 200 Owner's equity 11,375 Prepaid rent 175 Fumace and ovens 5,000 Equipment 3,000 Gas tanks 400 Truck 8.500 Total $17.500 Total $17.500