Discuss the distinction of the case-context (purpose of the study)

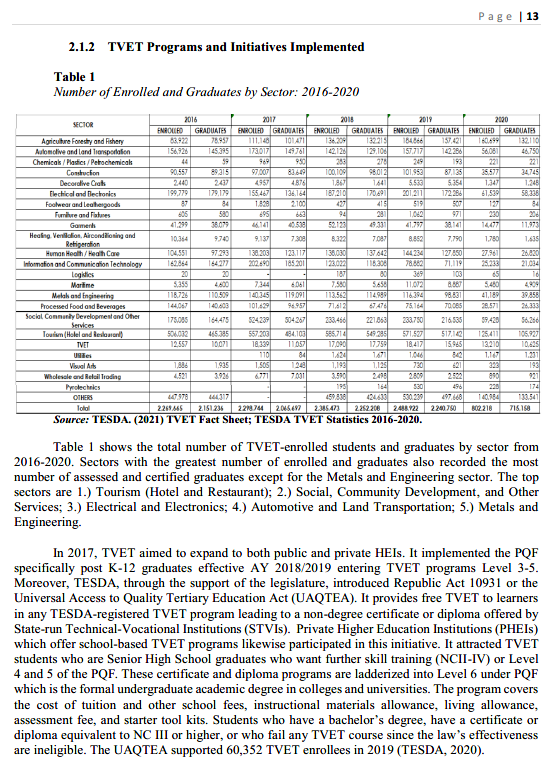

1. Descriptive study (TVET-TESDA)

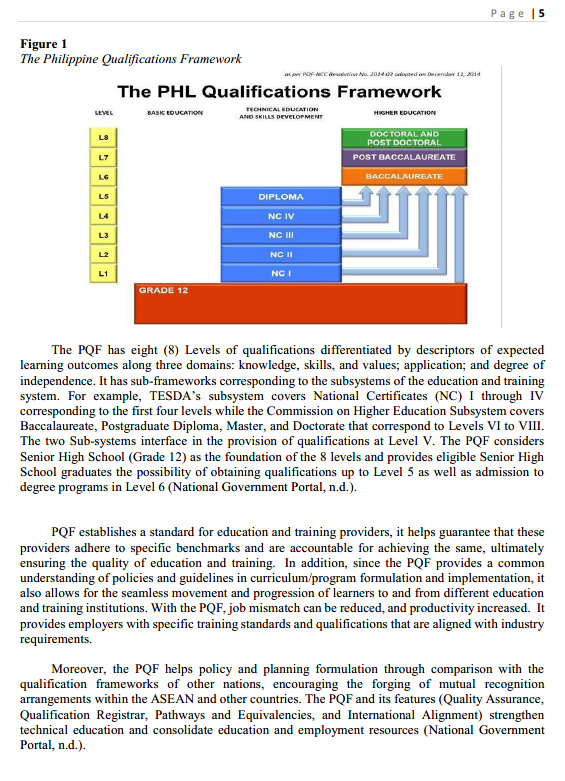

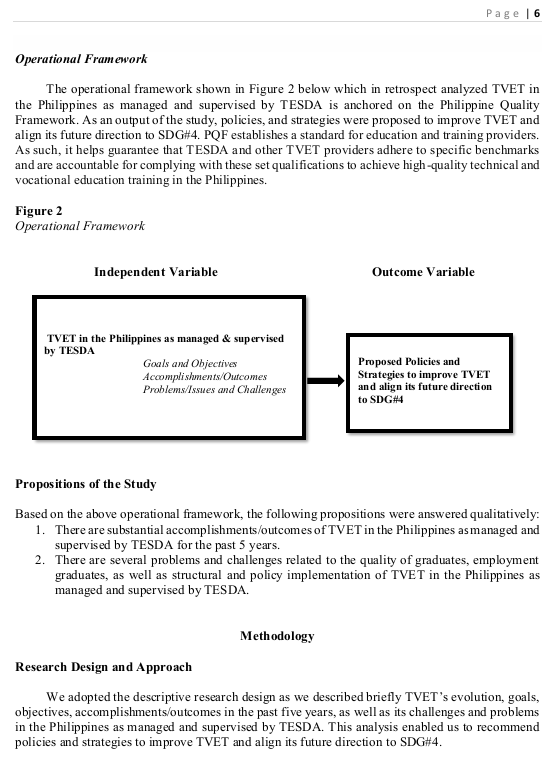

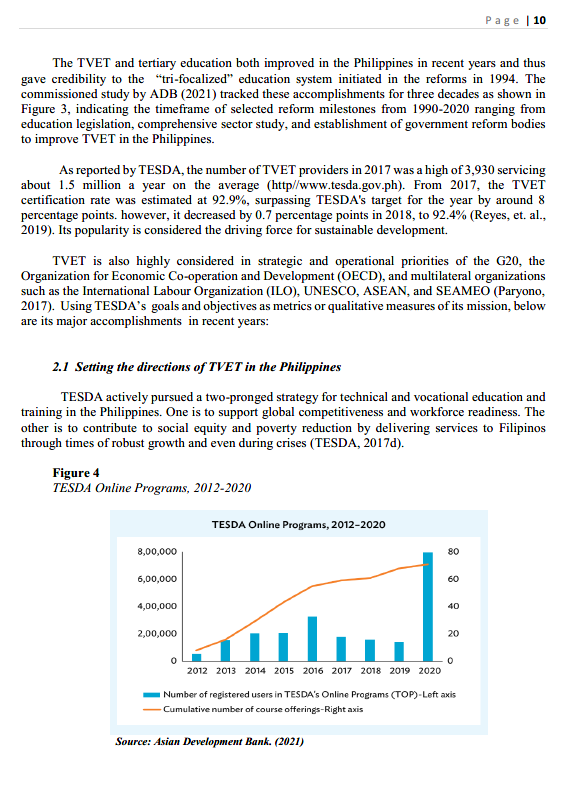

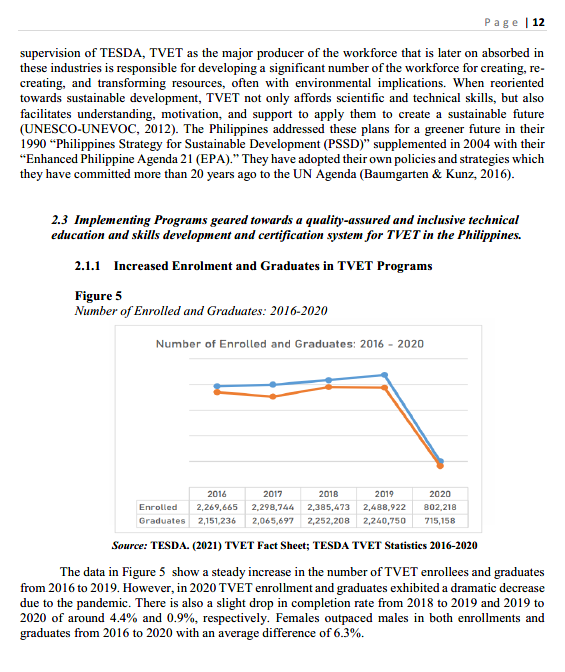

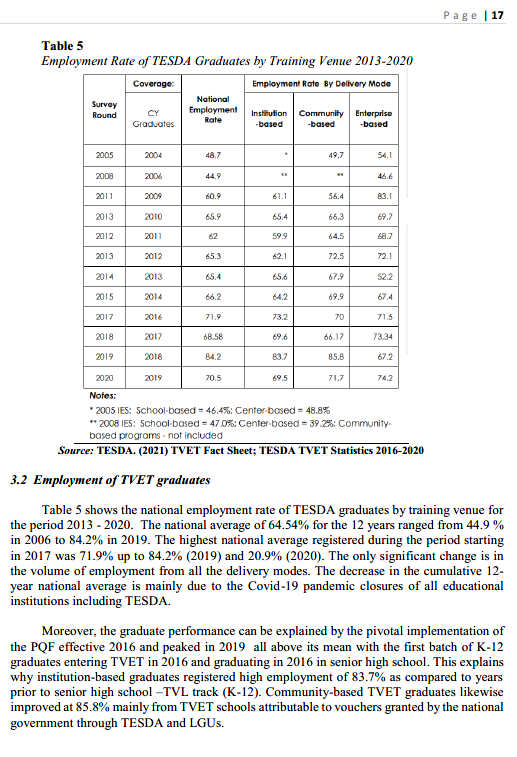

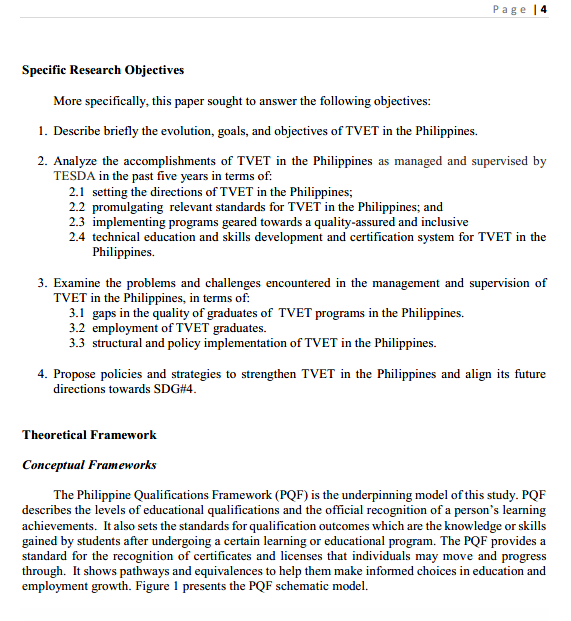

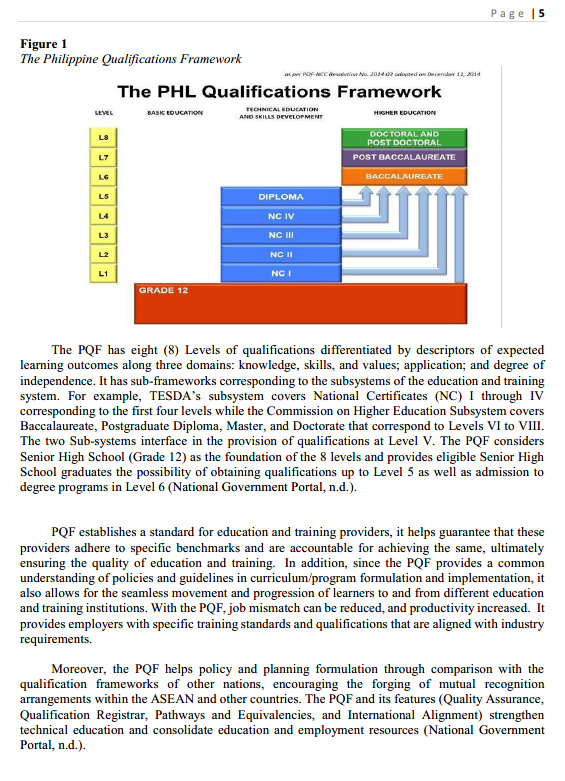

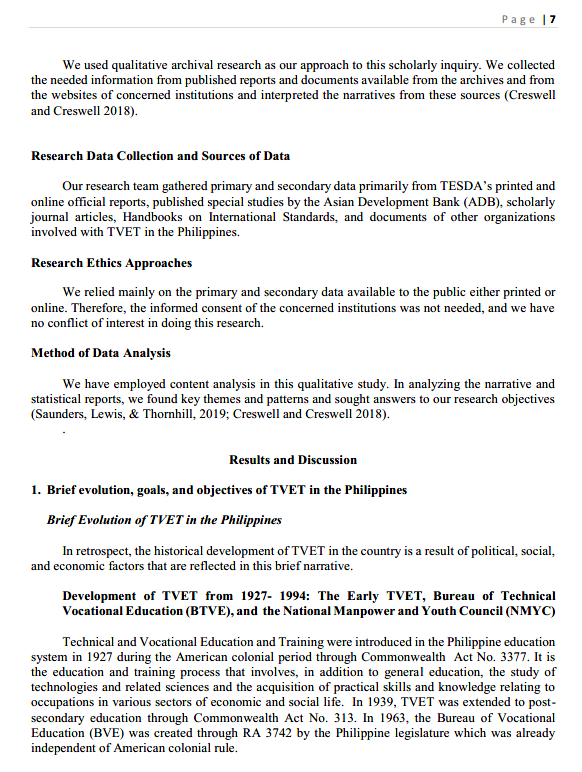

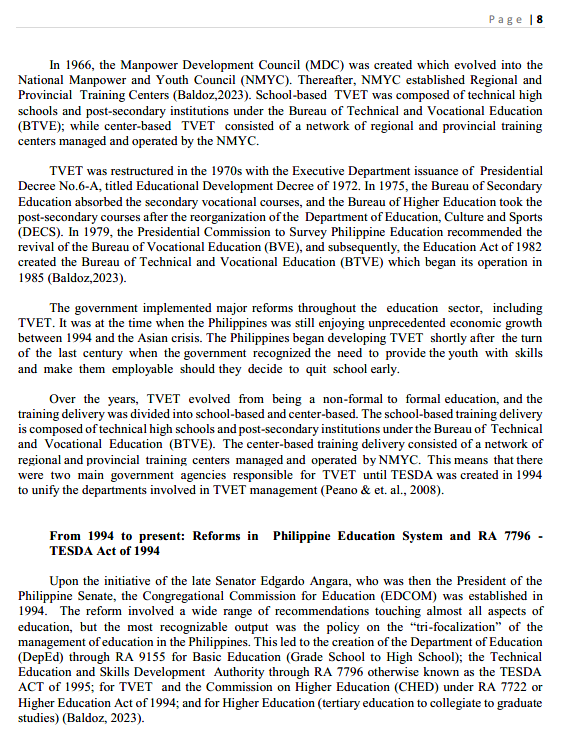

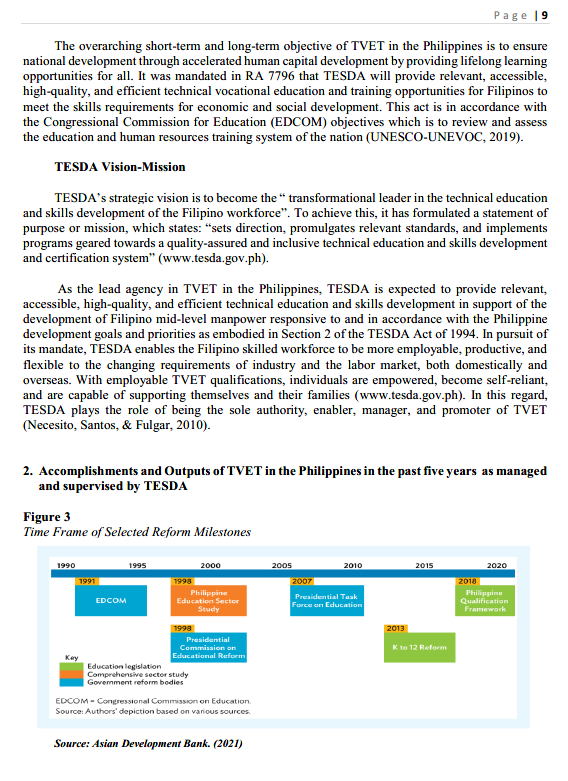

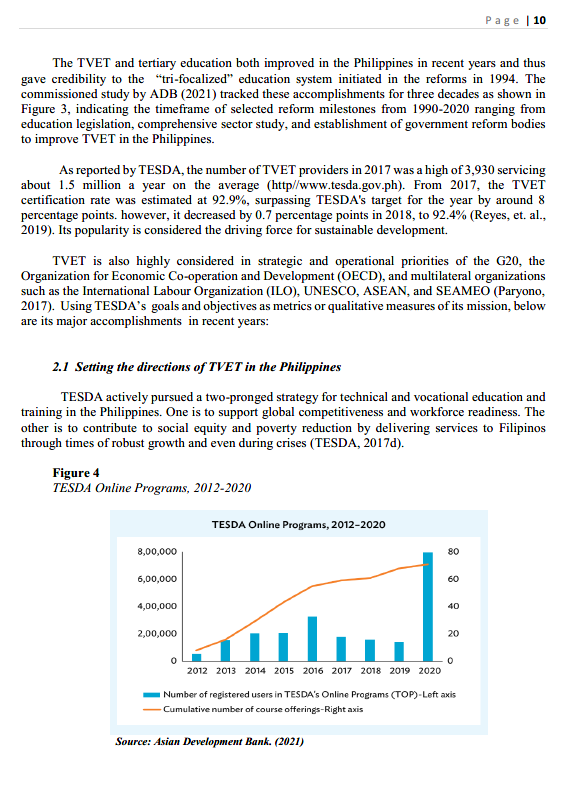

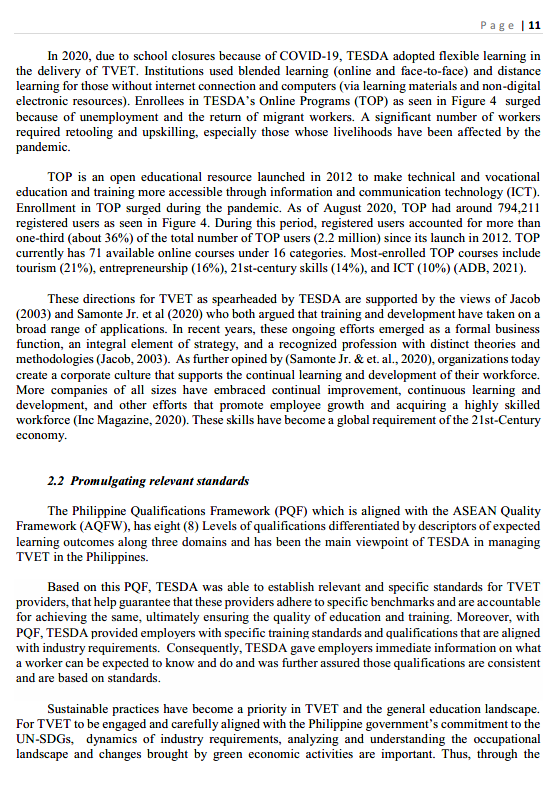

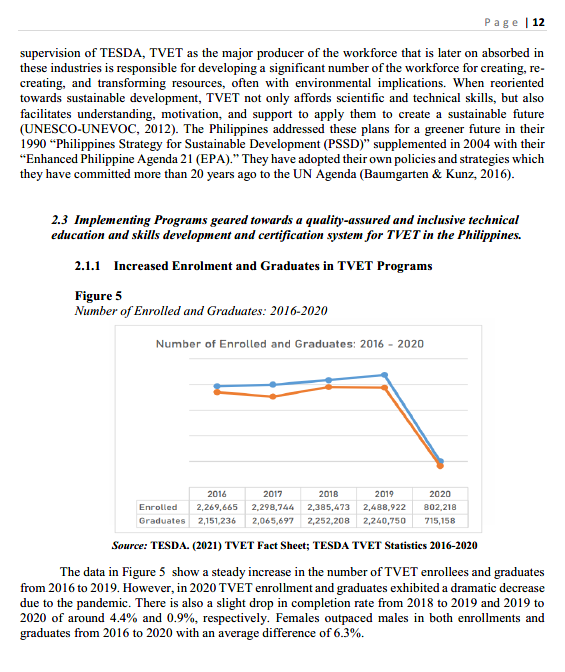

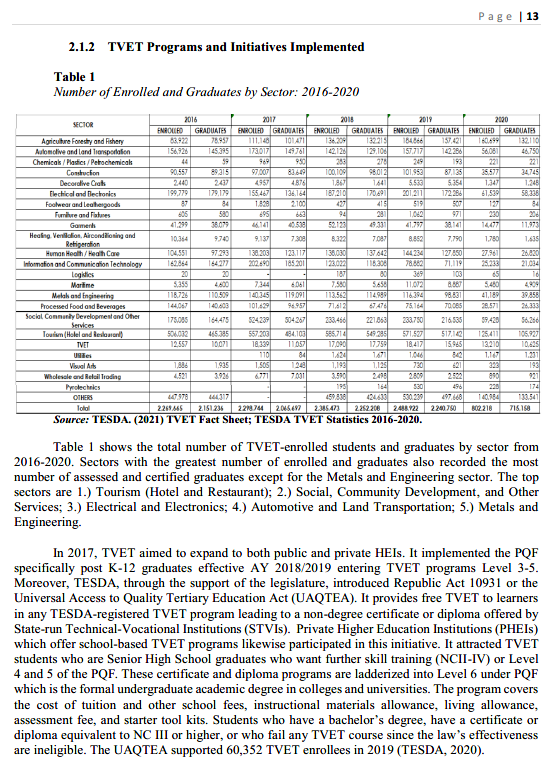

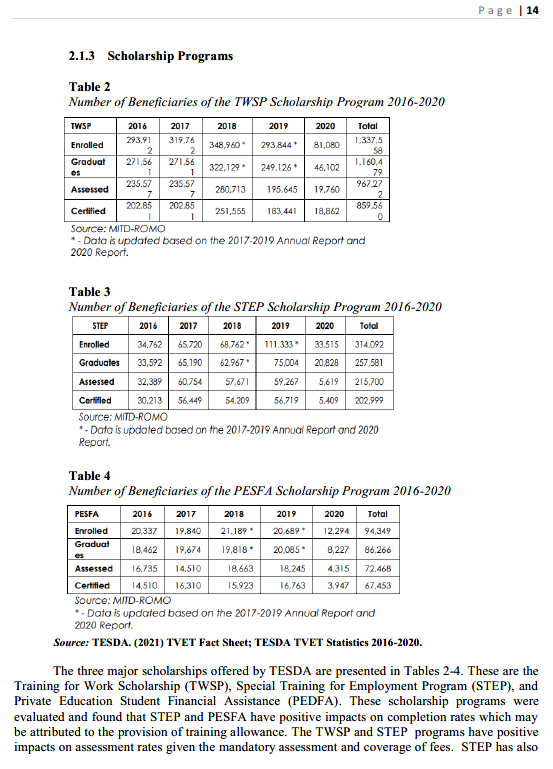

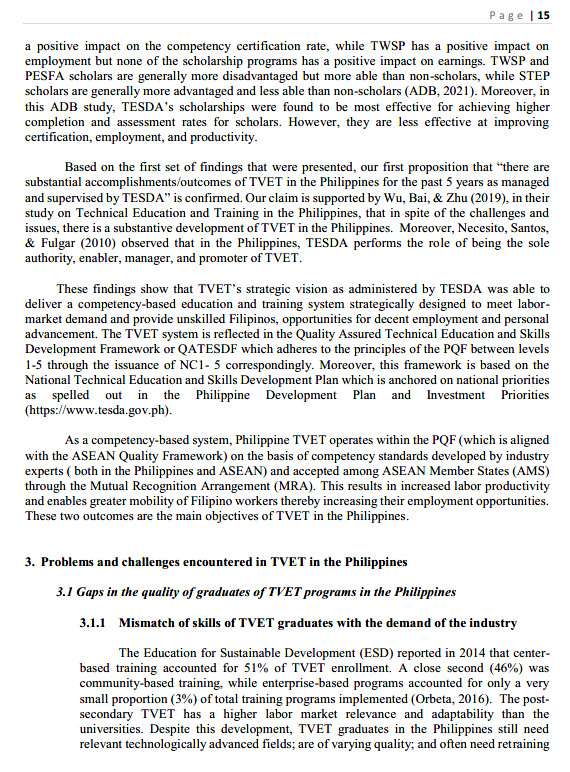

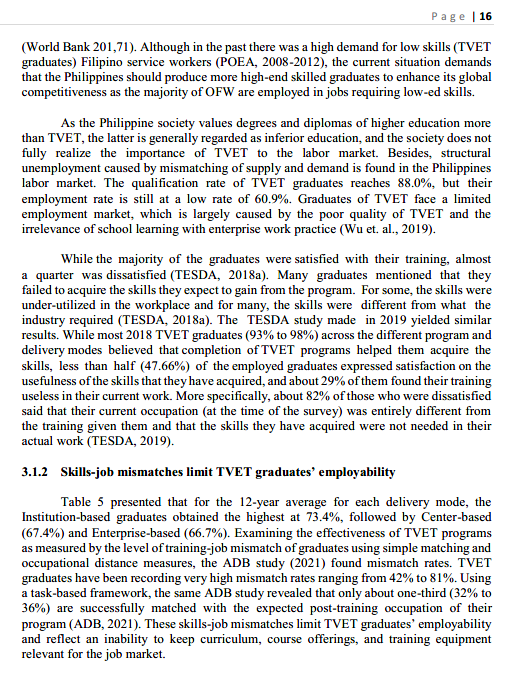

Technical and Vocational Education and Training in the Philippines: In Retrospect and Future Directions Divina M. Edralin and Ronald Pastrana Graduate School of Business, San Beda University Abstract Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) \#4: Quality Education and Lifelong Learning is one of the 17 United Nations SDGs. One of the eight targets is to ensure affordable and quality technical, vocational, and tertiary education. The Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) is the government agency tasked to manage and supervise technical education and skills development in the Philippines. In retrospect, we answered the research question: "What is the status of TVET in the Philippines as managed and supervised by TESDA and its future directions towards SDG\#4? We described the evolution, goals, objectives, accomplishments, and challenges of TVET in the Philippines. We used the Philippine Qualifications Framework as the underpinning model which establishes a standard for education and training providers. As the output of the study, we proposed policies and strategies to improve TVET to align its future direction to SDG\#4. We adopted the descriptive research design and the qualitative archival research approach. We gathered primary and secondary data that were available both online and in printed form. We employed content analysis in analyzing the narrative and statistical reports and found key themes and patterns that answered our research objectives. Findings revealed that TVET in the Philippines began when introduced in the Philippine education system in 1927 through Commonwealth Act No. 3377 which is the result of the dynamics of economic, social, and political factors. Over the years, the government implemented major reforms throughout the education sector, including TVET. With this effort, TVET evolved from being a non-formal to formal education, and the training delivery was divided into school-based and center-based, which created two main government agencies responsible for TVET until TESDA was established in 1994 to unify the departments involved in TVET management. There were considerable accomplishments and outcomes of TVET in the Philippines in the past years such as setting the direction of TVET in the Philippines and promulgating relevant standards. These strategic efforts contributed to the employment of TVET graduates, improving the quality of their skills needed by the industry, and having a clearer policy direction on how TVET is implemented in the country. There were several problems and challenges encountered in the supervision and implementation of TVET by TESDA. These are related to the poor quality of graduates, low employment of graduates, as well as weak structural and policy implementation of TVET in the Philippines as shown by the lack of closer coordination among the TVET stakeholders. We recommended aligning the curriculum development of TVET with the present Philippine Development Plan 2022-2028 and the needs of the industry including the demands of Industry 4.0 to strengthen TVET in the Philippines and align its future direction with SDGH4. Background of the Study The United Nations launched the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2015 which consists of 17 goals and 169 related targets aimed at tackling the global grand challenges of our era. This includes poverty, health and well-being, quality education, gender equality, decent work, and climate change. These 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were the result of cross-sector collaboration among multiple stakeholders from 193 countries, including representatives of governments, companies, and civil societies. The ultimate objective of the Agenda is to stimulate immediate action to protect our planet and ensure a more sustainable future for all (Lu et al., 2015). Among these 17 SDGs is SDG 4: Quality Education and Lifelong Learning. It has seven defined indicators and eight targets namely, ensure quality primary and secondary education, ensure quality early childhood development and pre-primary education, ensure affordable and quality technical, vocational, and tertiary education, and increase youth and adult relevant skills, among others. The targets include the proportion rate of youth and adults in formal and non-formal education and training, the participation rate in organized learning by sex, the proportion of youth and adults with information and communication technology skills, etc. Ensuring access to primary and secondary, tertiary, and technical-vocational education are three of the seven defined Quality Education indicators (UN Sustainable Development Goals Report, 2017; Report of the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators (E/CN.3/2016/2/Rev.1), 2016, as cited in Edralin and Pastrana, 2022). Several of the SDGs have placed prominence on the need to enhance the role of technical and vocational education and training (TVET). In the Philippines, many universities, besides providing higher education, also offer TVET programs as well as vocational course training certified by the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA). Some bachelor programs and diploma programs of universities explored the mode of ladderized training to offer TVET and academic education to students at different stages of their study. In a four-year bachelor's program of the mode of ladderized training, the first year is mainly dedicated to vocational training. At the end of the year, students may attend a TESDA certificate test to acquire a national certificate; the education in the following three years integrates academic education and TVET; upon graduation, students can acquire a bachelor's diploma and degree (Wu, Bai, \& Zhu, 2019). The Philippine Quality Framework (PQF) through E.O. Series 2012 was established as a national policy. It describes the levels of educational qualifications and sets the standards for qualification outcomes. It is a quality-assured national system for the development, recognition, and award of qualifications based on standards of knowledge, skills, and values acquired in different ways and methods by learners and workers of a certain country. This national policy covers all sectors, levels, and modes of delivery of the Philippines' tri-focalized education system: basic education, technical vocational education, and training (TVET), higher education; and all institutions and systems which provide training, specializations, skills, and competencies, professional experience or through life-long learning (TESDA, 2012). Page | 3 On the other hand, TESDA is the government agency tasked to manage and supervise technical education and skills development in the Philippines. It was created by virtue of Republic Act 7796 , otherwise known as the "Technical Education and Skills Development Act of 1994". The said Act integrated the functions of the former National Manpower and Youth Council (NMYC), the Bureau of Technical-Vocational Education of the Department of Education, Culture and Sports (BTVEDECS), and the Office of Apprenticeship of the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE). TESDA's vision is to produce transformational leaders in the technical education and skills development of the Filipino workforce; while its mission is to set the direction, promulgate relevant standards, and implement programs geared toward a quality-assured and inclusive technical education and skills development and certification system (https://www.tesda.gov.ph). TESDA actively pursues a two-pronged strategy for technical and vocational education and training (TVET) in the Philippines. One is to support global competitiveness and workforce readiness. The other is to contribute to social equity and poverty reduction by delivering services to Filipinos through times of robust growth and even during crises. Anchored in the National Technical Education and Skills Development Plan 2018-2022 and aligned with the Philippine Development Plan 2017-2022, both prongs of the strategy firmly define the roles of TESDA and TVET in nationbuilding and economic development (ADB, 2021). In the study on Technical Education and Training in the Philippines (Wu, Bai, \& Zhu 2019), it was recognized that despite the substantive development of TVET in the Philippines, the infrastructure of TVET is yet to be strengthened. Skilled workers have a low degree of international skills, thus lacking skill advantages among international competitors. People's work tasks often mismatch with their level of skills. It was further noted from the same study that graduates of TVET face a limited employment market, which is largely caused by the poor quality of TVET and the irrelevancy of school learning with enterprise work practices. This revealed that the quality of TVET in the Philippines is yet to be improved to be able to contribute to achieving SDGH4. Among the ten competitive industries planned to develop in the Philippines, many skilled workers migrate to other industries as their level of skills fails to reach standards. It was established in the same study that as the Philippine society values degrees and diplomas of higher education more than TVET, the latter is generally regarded as inferior education, and the society does not fully realize the importance of TVET to the labor market (Wu, Bai, \& Zhu, 2019). They also contend that despite the emergence of some stepwise programs inside higher education attempting to integrate TVET and regular education, overall, it is difficult for the TESDA to get involved due to the delimiting regulatory mechanism, especially regarding TVET in the fields of higher education (Wu, Bai, \& Zhu, 2019). This shows that there are still many challenges that are facing the relationship and integration between TVET and formal education at various levels of the Philippine education system. Statement of Research Problem We examined in retrospect TVET in the Philippines. We aimed to answer the main question: "What is the status of TVET in the Philippines as managed and supervised by TESDA and its future directions towards SDG\#4? 2. Analyze the accomplishments of TVET in the Philippines as managed and supervised by TESDA in the past five years in terms of: 2.1 setting the directions of TVET in the Philippines; 2.2 promulgating relevant standards for TVET in the Philippines; and 2.3 implementing programs geared towards a quality-assured and inclusive 2.4 technical education and skills development and certification system for TVET in the Philippines. 3. Examine the problems and challenges encountered in the management and supervision of TVET in the Philippines, in terms of: 3.1 gaps in the quality of graduates of TVET programs in the Philippines. 3.2 employment of TVET graduates. 3.3 structural and policy implementation of TVET in the Philippines. 4. Propose policies and strategies to strengthen TVET in the Philippines and align its future directions towards SDGH4. Theoretical Framework Conceptual Frameworks The Philippine Qualifications Framework (PQF) is the underpinning model of this study. PQF describes the levels of educational qualifications and the official recognition of a person's learning achievements. It also sets the standards for qualification outcomes which are the knowledge or skills gained by students after undergoing a certain learning or educational program. The PQF provides a standard for the recognition of certificates and licenses that individuals may move and progress through. It shows pathways and equivalences to help them make informed choices in education and employment growth. Figure 1 presents the PQF schematic model. Figure 1 The Philippine Qualifications Framework The PQF has eight (8) Levels of qualifications differentiated by descriptors of expected learning outcomes along three domains: knowledge, skills, and values; application; and degree of independence. It has sub-frameworks corresponding to the subsystems of the education and training system. For example, TESDA's subsystem covers National Certificates (NC) I through IV corresponding to the first four levels while the Commission on Higher Education Subsystem covers Baccalaureate, Postgraduate Diploma, Master, and Doctorate that correspond to Levels VI to VIII. The two Sub-systems interface in the provision of qualifications at Level V. The PQF considers Senior High School (Grade 12) as the foundation of the 8 levels and provides eligible Senior High School graduates the possibility of obtaining qualifications up to Level 5 as well as admission to degree programs in Level 6 (National Government Portal, n.d.). PQF establishes a standard for education and training providers, it helps guarantee that these providers adhere to specific benchmarks and are accountable for achieving the same, ultimately ensuring the quality of education and training. In addition, since the PQF provides a common understanding of policies and guidelines in curriculum/program formulation and implementation, it also allows for the seamless movement and progression of learners to and from different education and training institutions. With the PQF, job mismatch can be reduced, and productivity increased. It provides employers with specific training standards and qualifications that are aligned with industry requirements. Moreover, the PQF helps policy and planning formulation through comparison with the qualification frameworks of other nations, encouraging the forging of mutual recognition arrangements within the ASEAN and other countries. The PQF and its features (Quality Assurance, Qualification Registrar, Pathways and Equivalencies, and International Alignment) strengthen technical education and consolidate education and employment resources (National Government Portal, n.d.). Operational Framework The operational framework shown in Figure 2 below which in retrospect analyzed TVET in the Philippines as managed and supervised by TESDA is anchored on the Philippine Quality Framework. As an output of the study, policies, and strategies were proposed to improve TVET and align its future direction to SDGH4. PQF establishes a standard for education and training providers. As such, it helps guarantee that TESDA and other TVET providers adhere to specific benchmarks and are accountable for complying with these set qualifications to achieve high-quality technical and vocational education training in the Philippines. Figure 2 Operational Framework Propositions of the Study Based on the above operational framework, the following propositions were answered qualitatively: 1. There are substantial accomplishments/outcomes of TVET in the Philippines asmanaged and supervised by TESDA for the past 5 years. 2. There are several problems and challenges related to the quality of graduates, employment graduates, as well as structural and policy implementation of TVET in the Philippines as managed and supervised by TESDA. Methodology Research Design and Approach We adopted the descriptive research design as we described briefly TVET's evolution, goals, objectives, accomplishments/outcomes in the past five years, as well as its challenges and problems in the Philippines as managed and supervised by TESDA. This analysis enabled us to recommend policies and strategies to improve TVET and align its future direction to SDG\#4. We used qualitative archival research as our approach to this scholarly inquiry. We collected the needed information from published reports and documents available from the archives and from the websites of concerned institutions and interpreted the narratives from these sources (Creswell and Creswell 2018). Research Data Collection and Sources of Data Our research team gathered primary and secondary data primarily from TESDA's printed and online official reports, published special studies by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), scholarly journal articles, Handbooks on International Standards, and documents of other organizations involved with TVET in the Philippines. Research Ethics Approaches We relied mainly on the primary and secondary data available to the public either printed or online. Therefore, the informed consent of the concerned institutions was not needed, and we have no conflict of interest in doing this research. Method of Data Analysis We have employed content analysis in this qualitative study. In analyzing the narrative and statistical reports, we found key themes and patterns and sought answers to our research objectives (Saunders, Lewis, \& Thornhill, 2019; Creswell and Creswell 2018). Results and Discussion 1. Brief evolution, goals, and objectives of TVET in the Philippines Brief Evolution of TVET in the Philippines In retrospect, the historical development of TVET in the country is a result of political, social, and economic factors that are reflected in this brief narrative. Development of TVET from 1927- 1994: The Early TVET, Bureau of Technical Vocational Education (BTVE), and the National Manpower and Youth Council (NMYC) Technical and Vocational Education and Training were introduced in the Philippine education system in 1927 during the American colonial period through Commonwealth Act No. 3377. It is the education and training process that involves, in addition to general education, the study of technologies and related sciences and the acquisition of practical skills and knowledge relating to occupations in various sectors of economic and social life. In 1939, TVET was extended to postsecondary education through Commonwealth Act No. 313. In 1963, the Bureau of Vocational Education (BVE) was created through RA 3742 by the Philippine legislature which was already independent of American colonial rule. Page 8 In 1966, the Manpower Development Council (MDC) was created which evolved into the National Manpower and Youth Council (NMYC). Thereafter, NMYC established Regional and Provincial Training Centers (Baldoz,2023). School-based TVET was composed of technical high schools and post-secondary institutions under the Bureau of Technical and Vocational Education (BTVE); while center-based TVET consisted of a network of regional and provincial training centers managed and operated by the NMYC. TVET was restructured in the 1970s with the Executive Department issuance of Presidential Decree No.6-A, titled Educational Development Decree of 1972. In 1975, the Bureau of Secondary Education absorbed the secondary vocational courses, and the Bureau of Higher Education took the post-secondary courses after the reorganization of the Department of Education, Culture and Sports (DECS). In 1979, the Presidential Commission to Survey Philippine Education recommended the revival of the Bureau of Vocational Education (BVE), and subsequently, the Education Act of 1982 created the Bureau of Technical and Vocational Education (BTVE) which began its operation in 1985 (Baldoz,2023). The government implemented major reforms throughout the education sector, including TVET. It was at the time when the Philippines was still enjoying unprecedented economic growth between 1994 and the Asian crisis. The Philippines began developing TVET shortly after the turn of the last century when the government recognized the need to provide the youth with skills and make them employable should they decide to quit school early. Over the years, TVET evolved from being a non-formal to formal education, and the training delivery was divided into school-based and center-based. The school-based training delivery is composed of technical high schools and post-secondary institutions under the Bureau of Technical and Vocational Education (BTVE). The center-based training delivery consisted of a network of regional and provincial training centers managed and operated by NMYC. This means that there were two main government agencies responsible for TVET until TESDA was created in 1994 to unify the departments involved in TVET management (Peano \& et. al., 2008). From 1994 to present: Reforms in Philippine Education System and RA 7796 TESDA Act of 1994 Upon the initiative of the late Senator Edgardo Angara, who was then the President of the Philippine Senate, the Congregational Commission for Education (EDCOM) was established in 1994. The reform involved a wide range of recommendations touching almost all aspects of education, but the most recognizable output was the policy on the "tri-focalization" of the management of education in the Philippines. This led to the creation of the Department of Education (DepEd) through RA 9155 for Basic Education (Grade School to High School); the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority through RA 7796 otherwise known as the TESDA ACT of 1995; for TVET and the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) under RA 7722 or Higher Education Act of 1994; and for Higher Education (tertiary education to collegiate to graduate studies) (Baldoz, 2023). The overarching short-term and long-term objective of TVET in the Philippines is to ensure national development through accelerated human capital development by providing lifelong learning opportunities for all. It was mandated in RA 7796 that TESDA will provide relevant, accessible, high-quality, and efficient technical vocational education and training opportunities for Filipinos to meet the skills requirements for economic and social development. This act is in accordance with the Congressional Commission for Education (EDCOM) objectives which is to review and assess the education and human resources training system of the nation (UNESCO-UNEVOC, 2019). TESDA Vision-Mission TESDA's strategic vision is to become the " transformational leader in the technical education and skills development of the Filipino workforce". To achieve this, it has formulated a statement of purpose or mission, which states: "sets direction, promulgates relevant standards, and implements programs geared towards a quality-assured and inclusive technical education and skills development and certification system" (www.tesda.gov.ph). As the lead agency in TVET in the Philippines, TESDA is expected to provide relevant, accessible, high-quality, and efficient technical education and skills development in support of the development of Filipino mid-level manpower responsive to and in accordance with the Philippine development goals and priorities as embodied in Section 2 of the TESDA Act of 1994. In pursuit of its mandate, TESDA enables the Filipino skilled workforce to be more employable, productive, and flexible to the changing requirements of industry and the labor market, both domestically and overseas. With employable TVET qualifications, individuals are empowered, become self-reliant, and are capable of supporting themselves and their families (www.tesda.gov.ph). In this regard, TESDA plays the role of being the sole authority, enabler, manager, and promoter of TVET (Necesito, Santos, \& Fulgar, 2010). 2. Accomplishments and Outputs of TVET in the Philippines in the past five years as managed and supervised by TESDA Figure 3 Time Frame of Selected Reform Milestones Source: Asian Development Bank. (2021) The TVET and tertiary education both improved in the Philippines in recent years and thus gave credibility to the "tri-focalized" education system initiated in the reforms in 1994. The commissioned study by ADB (2021) tracked these accomplishments for three decades as shown in Figure 3, indicating the timeframe of selected reform milestones from 1990-2020 ranging from education legislation, comprehensive sector study, and establishment of government reform bodies to improve TVET in the Philippines. As reported by TESDA, the number of TVET providers in 2017 was a high of 3,930 servicing about 1.5 million a year on the average (http//www.tesda.gov.ph). From 2017, the TVET certification rate was estimated at 92.9%, surpassing TESDA's target for the year by around 8 percentage points. however, it decreased by 0.7 percentage points in 2018 , to 92.4% (Reyes, et. al., 2019). Its popularity is considered the driving force for sustainable development. TVET is also highly considered in strategic and operational priorities of the G20, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and multilateral organizations such as the International Labour Organization (ILO), UNESCO, ASEAN, and SEAMEO (Paryono, 2017). Using TESDA's goals and objectives as metrics or qualitative measures of its mission, below are its major accomplishments in recent years: 2.1 Setting the directions of TVET in the Philippines TESDA actively pursued a two-pronged strategy for technical and vocational education and training in the Philippines. One is to support global competitiveness and workforce readiness. The other is to contribute to social equity and poverty reduction by delivering services to Filipinos through times of robust growth and even during crises (TESDA, 2017d). Figure 4 TESDA Online Programs, 2012-2020 Source: Asian Development Bank. (2021) In 2020 , due to school closures because of COVID-19, TESDA adopted flexible learning in the delivery of TVET. Institutions used blended learning (online and face-to-face) and distance learning for those without internet connection and computers (via learning materials and non-digital electronic resources). Enrollees in TESDA's Online Programs (TOP) as seen in Figure 4 surged because of unemployment and the return of migrant workers. A significant number of workers required retooling and upskilling, especially those whose livelihoods have been affected by the pandemic. TOP is an open educational resource launched in 2012 to make technical and vocational education and training more accessible through information and communication technology (ICT). Enrollment in TOP surged during the pandemic. As of August 2020, TOP had around 794,211 registered users as seen in Figure 4. During this period, registered users accounted for more than one-third (about 36% ) of the total number of TOP users (2.2 million) since its launch in 2012. TOP currently has 71 available online courses under 16 categories. Most-enrolled TOP courses include tourism ( 21% ), entrepreneurship (16\%), 21st-century skills (14\%), and ICT (10\%) (ADB, 2021). These directions for TVET as spearheaded by TESDA are supported by the views of Jacob (2003) and Samonte Jr. et al (2020) who both argued that training and development have taken on a broad range of applications. In recent years, these ongoing efforts emerged as a formal business function, an integral element of strategy, and a recognized profession with distinct theories and methodologies (Jacob, 2003). As further opined by (Samonte Jr. \& et. al., 2020), organizations today create a corporate culture that supports the continual learning and development of their workforce. More companies of all sizes have embraced continual improvement, continuous learning and development, and other efforts that promote employee growth and acquiring a highly skilled workforce (Inc Magazine, 2020). These skills have become a global requirement of the 21 st-Century economy. 2.2 Promulgating relevant standards The Philippine Qualifications Framework (PQF) which is aligned with the ASEAN Quality Framework (AQFW), has eight (8) Levels of qualifications differentiated by descriptors of expected learning outcomes along three domains and has been the main viewpoint of TESDA in managing TVET in the Philippines. Based on this PQF, TESDA was able to establish relevant and specific standards for TVET providers, that help guarantee that these providers adhere to specific benchmarks and are accountable for achieving the same, ultimately ensuring the quality of education and training. Moreover, with PQF, TESDA provided employers with specific training standards and qualifications that are aligned with industry requirements. Consequently, TESDA gave employers immediate information on what a worker can be expected to know and do and was further assured those qualifications are consistent and are based on standards. Sustainable practices have become a priority in TVET and the general education landscape. For TVET to be engaged and carefully aligned with the Philippine government's commitment to the UN-SDGs, dynamics of industry requirements, analyzing and understanding the occupational landscape and changes brought by green economic activities are important. Thus, through the supervision of TESDA, TVET as the major producer of the workforce that is later on absorbed in these industries is responsible for developing a significant number of the workforce for creating, recreating, and transforming resources, often with environmental implications. When reoriented towards sustainable development, TVET not only affords scientific and technical skills, but also facilitates understanding, motivation, and support to apply them to create a sustainable future (UNESCO-UNEVOC, 2012). The Philippines addressed these plans for a greener future in their 1990 "Philippines Strategy for Sustainable Development (PSSD)" supplemented in 2004 with their "Enhanced Philippine Agenda 21 (EPA)." They have adopted their own policies and strategies which they have committed more than 20 years ago to the UN Agenda (Baumgarten \& Kunz, 2016). 2.3 Implementing Programs geared towards a quality-assured and inclusive technical education and skills development and certification system for TVET in the Philippines. 2.1.1 Increased Enrolment and Graduates in TVET Programs Figure 5 Number of Enrolled and Graduates: 2016-2020 Source: TESDA. (2021) TVET Fact Sheet; TESDA TVET Statistics 2016-2020 The data in Figure 5 show a steady increase in the number of TVET enrollees and graduates from 2016 to 2019. However, in 2020 TVET enrollment and graduates exhibited a dramatic decrease due to the pandemic. There is also a slight drop in completion rate from 2018 to 2019 and 2019 to 2020 of around 4.4% and 0.9%, respectively. Females outpaced males in both enrollments and graduates from 2016 to 2020 with an average difference of 6.3%. 2.1.2 TVET Programs and Initiatives Implemented Table 1 Number of Enrolled and Graduates by Sector: 2016-2020 Table 1 shows the total number of TVET-enrolled students and graduates by sector from 2016-2020. Sectors with the greatest number of enrolled and graduates also recorded the most number of assessed and certified graduates except for the Metals and Engineering sector. The top sectors are 1.) Tourism (Hotel and Restaurant); 2.) Social, Community Development, and Other Services; 3.) Electrical and Electronics; 4.) Automotive and Land Transportation; 5.) Metals and Engineering. In 2017, TVET aimed to expand to both public and private HEIs. It implemented the PQF specifically post K-12 graduates effective AY 2018/2019 entering TVET programs Level 3-5. Moreover, TESDA, through the support of the legislature, introduced Republic Act 10931 or the Universal Access to Quality Tertiary Education Act (UAQTEA). It provides free TVET to learners in any TESDA-registered TVET program leading to a non-degree certificate or diploma offered by State-run Technical-Vocational Institutions (STVIs). Private Higher Education Institutions (PHEIs) which offer school-based TVET programs likewise participated in this initiative. It attracted TVET students who are Senior High School graduates who want further skill training (NCII-IV) or Level 4 and 5 of the PQF. These certificate and diploma programs are ladderized into Level 6 under PQF which is the formal undergraduate academic degree in colleges and universities. The program covers the cost of tuition and other school fees, instructional materials allowance, living allowance, assessment fee, and starter tool kits. Students who have a bachelor's degree, have a certificate or diploma equivalent to NC III or higher, or who fail any TVET course since the law's effectiveness are ineligible. The UAQTEA supported 60,352 TVET enrollees in 2019 (TESDA, 2020). Table 2 Number of Beneficiaries of the TWSP Scholarship Program 2016-2020 Source: MITD-ROMO * - Data is updated based on the 2017-2019 Annual Report and 2020 Report. Table 3 Number of Beneficiaries of the STEP Scholarship Program 2016-2020 Source: MITD-ROMO *- Data is updated based on the 2017-2019 Annual Report and 2020 Report. Table 4 Number of Beneficiaries of the PESFA Scholarship Program 2016-2020 Jource: MIIU-KUMU *- Data is updated based on the 2017-2019 Annual Repori and 2020 Report. Source: TESDA. (2021) TVET Fact Sheet; TESDA TVET Statistics 2016-2020. The three major scholarships offered by TESDA are presented in Tables 2-4. These are the Training for Work Scholarship (TWSP), Special Training for Employment Program (STEP), and Private Education Student Financial Assistance (PEDFA). These scholarship programs were evaluated and found that STEP and PESFA have positive impacts on completion rates which may be attributed to the provision of training allowance. The TWSP and STEP programs have positive impacts on assessment rates given the mandatory assessment and coverage of fees. STEP has also a positive impact on the competency certification rate, while TWSP has a positive impact on employment but none of the scholarship programs has a positive impact on earnings. TWSP and PESFA scholars are generally more disadvantaged but more able than non-scholars, while STEP scholars are generally more advantaged and less able than non-scholars (ADB, 2021). Moreover, in this ADB study, TESDA's scholarships were found to be most effective for achieving higher completion and assessment rates for scholars. However, they are less effective at improving certification, employment, and productivity. Based on the first set of findings that were presented, our first proposition that "there are substantial accomplishments/outcomes of TVET in the Philippines for the past 5 years as managed and supervised by TESDA" is confirmed. Our claim is supported by Wu, Bai, \& Zhu (2019), in their study on Technical Education and Training in the Philippines, that in spite of the challenges and issues, there is a substantive development of TVET in the Philippines. Moreover, Necesito, Santos, \& Fulgar (2010) observed that in the Philippines, TESDA performs the role of being the sole authority, enabler, manager, and promoter of TVET. These findings show that TVET's strategic vision as administered by TESDA was able to deliver a competency-based education and training system strategically designed to meet labormarket demand and provide unskilled Filipinos, opportunities for decent employment and personal advancement. The TVET system is reflected in the Quality Assured Technical Education and Skills Development Framework or QATESDF which adheres to the principles of the PQF between levels 1-5 through the issuance of NC1- 5 correspondingly. Moreover, this framework is based on the National Technical Education and Skills Development Plan which is anchored on national priorities as spelled out in the Philippine Development Plan and Investment Priorities (https://www.tesda.gov.ph). As a competency-based system, Philippine TVET operates within the PQF (which is aligned with the ASEAN Quality Framework) on the basis of competency standards developed by industry experts ( both in the Philippines and ASEAN) and accepted among ASEAN Member States (AMS) through the Mutual Recognition Arrangement (MRA). This results in increased labor productivity and enables greater mobility of Filipino workers thereby increasing their employment opportunities. These two outcomes are the main objectives of TVET in the Philippines. 3. Problems and challenges encountered in TVET in the Philippines 3.1 Gaps in the quality of graduates of TVET programs in the Philippines 3.1.1 Mismatch of skills of TVET graduates with the demand of the industry The Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) reported in 2014 that centerbased training accounted for 51% of TVET enrollment. A close second (46\%) was community-based training, while enterprise-based programs accounted for only a very small proportion (3\%) of total training programs implemented (Orbeta, 2016). The postsecondary TVET has a higher labor market relevance and adaptability than the universities. Despite this development, TVET graduates in the Philippines still need relevant technologically advanced fields; are of varying quality; and often need retraining (World Bank 201,71). Although in the past there was a high demand for low skills (TVET graduates) Filipino service workers (POEA, 2008-2012), the current situation demands that the Philippines should produce more high-end skilled graduates to enhance its global competitiveness as the majority of OFW are employed in jobs requiring low-ed skills. As the Philippine society values degrees and diplomas of higher education more than TVET, the latter is generally regarded as inferior education, and the society does not fully realize the importance of TVET to the labor market. Besides, structural unemployment caused by mismatching of supply and demand is found in the Philippines labor market. The qualification rate of TVET graduates reaches 88.0%, but their employment rate is still at a low rate of 60.9%. Graduates of TVET face a limited employment market, which is largely caused by the poor quality of TVET and the irrelevance of school learning with enterprise work practice (Wu et. al., 2019). While the majority of the graduates were satisfied with their training, almost a quarter was dissatisfied (TESDA, 2018a). Many graduates mentioned that they failed to acquire the skills they expect to gain from the program. For some, the skills were under-utilized in the workplace and for many, the skills were different from what the industry required (TESDA, 2018a). The TESDA study made in 2019 yielded similar results. While most 2018 TVET graduates (93\% to 98% ) across the different program and delivery modes believed that completion of TVET programs helped them acquire the skills, less than half (47.66\%) of the employed graduates expressed satisfaction on the usefulness of the skills that they have acquired, and about 29% of them found their training useless in their current work. More specifically, about 82% of those who were dissatisfied said that their current occupation (at the time of the survey) was entirely different from the training given them and that the skills they have acquired were not needed in their actual work (TESDA, 2019). 3.1.2 Skills-job mismatches limit TVET graduates' employability Table 5 presented that for the 12 -year average for each delivery mode, the Institution-based graduates obtained the highest at 73.4%, followed by Center-based (67.4\%) and Enterprise-based (66.7\%). Examining the effectiveness of TVET programs as measured by the level of training-job mismatch of graduates using simple matching and occupational distance measures, the ADB study (2021) found mismatch rates. TVET graduates have been recording very high mismatch rates ranging from 42% to 81%. Using a task-based framework, the same ADB study revealed that only about one-third ( 32% to 36% ) are successfully matched with the expected post-training occupation of their program (ADB, 2021). These skills-job mismatches limit TVET graduates' employability and reflect an inability to keep curriculum, course offerings, and training equipment relevant for the job market. Table 5 Employment Rate of TESDA Graduates by Training Venue 2013-2020 * 2005 IES: 5 chool-based =46.4%: Center-bosed =48.8% *4 2008 IES: 5chool-based = 47.0F: Center-bosed = 39.2% : Community- based programs - not included Source: TESDA. (2021) TVET Fact Sheet; TESDA TVET Statistics 2016-2020 3.2 Employment of TVET graduates Table 5 shows the national employment rate of TESDA graduates by training venue for the period 20132020. The national average of 64.54% for the 12 years ranged from 44.9% in 2006 to 84.2% in 2019 . The highest national average registered during the period starting in 2017 was 71.9% up to 84.2% (2019) and 20.9% (2020). The only significant change is in the volume of employment from all the delivery modes. The decrease in the cumulative 12 year national average is mainly due to the Covid-19 pandemic closures of all educational institutions including TESDA. Moreover, the graduate performance can be explained by the pivotal implementation of the PQF effective 2016 and peaked in 2019 all above its mean with the first batch of K-12 graduates entering TVET in 2016 and graduating in 2016 in senior high school. This explains why institution-based graduates registered high employment of 83.7% as compared to years prior to senior high school-TVL track (K-12). Community-based TVET graduates likewise improved at 85.8% mainly from TVET schools attributable to vouchers granted by the national government through TESDA and LGUs. The employment rate of TESDA graduates by sector from 2018-2020 as shown in Table 6 indicates a higher percentage (92.5%) of employed are in the utilities, decorative arts, wholesale and retail trading, and garments sectors; while 72.5% were in construction, human/health care and tourism at 72.5%; and about 65.6% in ICT, Maritime, Electrical and Electronics sectors. These data indicate that TVET graduates are more employed in low-skillsbased jobs (e.g., retail and trading) than high-skills-based jobs (e.g., ICT, electronics, and metals, and engineering). Table 6 Employment Rate of TESDA Graduates by Sector: 2018, 2019, 2020 Source: TESDA. (2021) TVET Fact Sheet; TESDA TVET Statistics 2016-2020 3.2.1 Public perception that TVET is inferior when compared with that of formal /higher education. TVET graduates were compared to those who were only taught at secondary school or below. Comparisons were also made with those who pursued tertiary education, such as the university. TVET graduates are more likely to be employed and receive a higher wage than those who only studied at secondary school or below (Vandenberg \& Laranjo, 2021). Skilled workers have a low degree of international skills, thus lacking skill advantages among international competitors. People's work tasks often mismatch with their level of skills. Among the ten competitive industries planned to develop in the Page|20 influence on the employability of TVET graduates who were unemployed before the training (Talento, et. al., 2022). 3.2.3 Wide disparity in Pay of TVET graduates On the impact of vocational education on wages in the private sector and using labor force survey data from the Philippines for 2015 , about 80% of those who received TVET did so at the post-secondary level. TVET graduates earned higher wages than those who only completed secondary school. However, for students who studied both TVET and at the tertiary level, wages were lower than for those who undertook only tertiary studies. The author suggested there may be a "penalty" for adding TVET to university education. In this study, propensity score matching (PSM) generated similar results, although statistical significance was not achieved, and balancing properties were not met under certain specifications. For example, those with TVET earned higher wages than those with only secondary school education, and while the results were statistically significant, a test of balancing properties was not satisfied. (Olfindo, 2018). Furthermore, the impact of TVET on wages in the Philippines using data from the Labor Force Survey of 2014 revealed similar significant effects for TVET graduates relative to those who completed only secondary school. However, the estimates did not control for economic background, parents' education, or other factors that might account for differences in ability (Olfindo, 2018). 3.3 Structural and Policy Implementation of TVET in the Philippines 3.3.1 Lack of coordination among government agencies regarding the Philippine Credit Transfer System (PCTS) and ladderized progression of TVET to provide pathways and equivalencies to formal education The tri-focalized system of education in the Philippines introduced in 1994 through various legislative acts resulted in having three distinct agencies (i.e DepED, CHED, and TESDA) focusing on basic education, higher education, and TVET, respectively. Although these recent education reforms have boosted the TVET sector's growth, TVET short-term certificate programs are not yet ladderized to formal education. There is still no "equivalency system" by which these TVET programs are given credit in a formal bachelor's degree at the tertiary level. Major challenges in the implementation of programs in the TVET system include the policies, curriculum, practices, and in providing the needed resources (Alto et. al., 2017). The PQF describes the levels of educational qualifications and sets the standards for qualification outcomes. It is a quality-assured national system for the development, recognition, and award of qualifications based on standards of knowledge, skills, and values acquired in different ways and methods by learners and workers of the country (PQF,2018). However, one of its main objectives is to "support the development and maintenance of pathways and equivalencies that enable access to qualifications and to assist individuals to move easily and readily between different education and training sectors and between these sectors and the labor market ((https://www.tesda.gov). Our develop in the Philippines, many skilled workers migrate to other industries since their level of skills fails to reach standards. Moreover, it was also established in the same study (Wu et. al., 2019) that as the Philippine society values degrees and diplomas of higher education more than TVET, the latter is generally regarded as inferior education and the society does not fully realize the importance of TVET to the labor market. Besides, structural unemployment caused by mismatching of supply and demand is found in the Philippines labor market. The qualification rate of TVET graduates reached 88.0%, but their employment rate is still at a low rate of 60.9%. Graduates of TVET face a limited employment market, which is largely caused by the poor quality of TVET and the irrelevancy of school learning with enterprise work practices (Wu et. al., 2019). 4. Proposed policies and strategies to strengthen TVET in the Philippines and align its future direction with SDGH4 TVET and tertiary education have both improved in the Philippines in recent years. In 2017, the TVET certification rate was estimated at 92.9%, surpassing TESDA's target for the year by around 8% points. This however decreased by 0.7 percentage points in 2018 , at 92.4% (Reyes, et. al., 2019). Its popularity is considered the driving force for sustainable development. TVET is also highly considered a strategic and operational priority of the G20, the OECD, and multilateral organizations such as the ILO, UNESCO, ASEAN, and SEAMEO (Paryono, 2017). Moreover, under UN-SDG 4: Quality Education and Lifelong Learning, there are seven defined indicators and eight targets. Ensuring access to primary and secondary, tertiary, and technical-vocational education are three of the seven defined Quality Education indicators (UN Sustainable Development Goals Report, 2017; Report of the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators (E/CN.3/2016/2/Rev.1),2016). In this context and founded on the results of our study, we propose the following policies and strategies to improve TVET in the Philippines and align its future direction with SDG #4. 1. Align the curriculum development of TVET with the present Philippine Development Plan 2022-2028 and the needs of the industry including the demands of Industry 4.0. 1.1. Harmonize and coordinate the three levels of the "tri-focalized education system" in the Philippines initiated in 1994 and amended through the implementation of the PQF in 2012 aimed at aligning with the AQFW. This will allow TVET graduates to proceed to formal education at the tertiary level. This requires equivalency and a credit system through the Philippine Credit Transfer System (PCTS) for the three sectors- DepED (Senior High School-TVL track), TESDA, and CHED. TESDA subsystem covers NC1 through IV corresponding to the first four levels of the PQF, while the CHED sub-system covers Baccalaureate, postgraduate diploma to Doctorate that corresponds to Levels 6 to 8 of the Philippine Qualifications Framework. The two sub-systems interface in the provision of diploma programs at Level 5. This is the contentious point in the PQF which needs harmonization and coordination between the two government agencies. 1.2. Expand qualification standards of TVET (Levels 3-5) using international standards such as the European Quality Framework to increase the potential of Filipino workers in gaining employment in high-skills jobs abroad. This answers one of the main objectives of the PQF i.e. to align domestic qualification standards with the international qualifications framework thereby enhancing recognition of the value and comparability of Philippine qualifications and supporting the mobility of Filipino students and workers (https://www.TESDA. gov.ph). 1.3. Develop and improve learning materials in line with international standards. These materials must be continuously improved and updated based on recent trends in international education frameworks, and standards (e.g., Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), global citizenship education with an emphasis on human rights among others, and social inclusion, environmental sustainability, and social justice in the curriculum) (NEDA, 2023). These are concrete measures to align TVET with the UN-SG Agenda 2030, particularly SDG \# 4 (Quality Education and Lifelong Learning). 2. Strengthen linkages and partnerships of TVET training institutions and industry in the area of apprenticeship/On-the-Job Training (OJT) to enhance practical skills and knowledge of stateof-the-art technology and increase labor productivity. 2.1. Improve enterprise-based training (EBT) as a contemporary modality in TVET delivery. This proposed measure aims to incorporate the existing programs under the EBT administered by TESDA and expand the provision of training programs implemented within companies. The program can be a mix of workplace training and classroom-based learning following the German Model of Dual-Learning in TVET education (NEDA, 2023). 2.2. Reinforce partnerships among colleges and universities offering TVET, TESDA, and TVET Institutions, including linkages with industry associations, other government agencies, NGOs, and social enterprises. This must ensure TVET programs and initiatives will cater to community needs and priorities including entrepreneurship in various industries such as agri-business, hospitality and services, Information Technology, and construction among others. 2.3. Enact laws and formulate policies for apprenticeship to meet the industry provision in internship stipulated in the Labor Code. This will support the recommendation for improving TVET with TESDA as the main enabling agency. 3. Enhance employment opportunities and labor productivity as the ultimate metrics of the Quality-Assured Philippine Technical Education System by which the Philippine TVET system operates under PQF. 3.1. Increase employment opportunities by improving the quality of TVET training by TESDA and other TVET -certificate and diploma-granting institutions (colleges and universities, private institutions) under the supervision of TESDA and accrediting bodies such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), and other industry-based accrediting agencies. This entails developing alternative assessment and certification methods. Strengthening TVET through school-based and training institutions will be achieved through scholarships and voucher systems similar to the scheme in Senior High School. This means increasing the budgetary resources of TESDA which comes from the national budget (General Appropriation Act). 3.2. Improve labor productivity through the revision of the Labor Productivity Act of 1993 to make it responsive to the present time. Employment and productivity engagement are the ultimate metrics of the TVET system in the Philippines to effectively bring about the effective matching of labor supply and demand. This initiative will achieve more effective and wider cooperation among institutions like DOLE, DAP, TESDA, DEPED, CHED, and State Colleges and Universities (SUCs) and Private Higher Education Institutions (PHEIs). Conclusion In retrospect, the historical development of TVET in the country has its beginnings when introduced in the Philippine education system in 1927 through Commonwealth Act No. 3377, which is a result of the dynamics of political, social, and economic factors. TVET is the education and training process that involves, in addition to general education, the study of technologies and related sciences and the acquisition of practical skills and knowledge relating to occupations in various sectors of economic and social life. Over the years, the government implemented major reforms throughout the education sector, including TVET. With this effort, TVET evolved from being a non-formal to formal education, and the training delivery was divided into school-based and center-based. This means that there were two main government agencies responsible for TVET until TESDA was created in 1994 to unify the departments involved in TVET management (Peano \& et. al., 2008). The overarching short-term and long-term objective of TVET in the Philippines is to ensure national development through accelerated human capital development by providing lifelong learning opportunities for all. It was mandated in RA 7796 that TESDA will provide relevant, accessible, high-quality, and efficient technical vocational education and training opportunities for Filipinos to meet the skills requirements for economic and social development. In this regard, TESDA plays the role of being the sole authority, enabler, manager, and promoter of TVET (Necesito, Santos, \& Fulgar, 2010). Following the PQF standpoint, the TVET and tertiary education both improved in the Philippines in recent years, and thus gave credibility to the "tri-focalized" education system initiated in the reforms in 1994. TVET is also highly considered a strategic and operational priority of the G20, the OECD, and multilateral organizations such as the ILO, UNESCO, ASEAN, and SEAMEO Page | 25 There are substantial accomplishments and outcomes of TVET in the Philippines for the past 5 years as managed and supervised by TESDA. This is supported by Wu, Bai, \& Zhu (2019) in their study on Technical Education and Training in the Philippines, that in spite of the challenges and issues, there is a substantive development of TVET in the Philippines. Concretely, through TESDA, some of these achievements are setting the direction of TVET in the Philippines, promulgating relevant standards, and implementing programs geared towards a quality-assured and inclusive technical education and skills development and certification system for TVET in the Philippines. More importantly, the Asian Development Bank study (2021) reported that the two-pronged strategy of TVET in the Philippines is anchored in the National Technical Education and Skills Development Plan 2018-2022 and aligned with the Philippine Development Plan 2017-2022 ( as revised to 20222028). These firmly defined the roles of TESDA and the importance of TVET in nation-building and economic development. There are several problems and challenges related to the quality of graduates, employment graduates, as well as structural and policy implementation of TVET in the Philippines. This is also supported by Wu, Bai, \& Zhu (2019), who argued that despite the substantive development of TVET in the Philippines, the infrastructure of TVET is yet to be strengthened. Skilled workers have a low degree of international skills, thus lacking skill advantages among international competitors. Among the ten competitive industries planned to develop in the Philippines, many skilled workers migrate to other industries since their level of skills fails to reach standards. Moreover, the Philippine society values degrees and diplomas of higher education more than TVET. TVET is generally regarded as inferior education and society does not fully realize the importance of TVET to the labor market. Besides, structural unemployment caused by mismatching of supply and demand is found in the Philippines labor market. Graduates of TVET face a limited employment market, which is largely caused by the poor quality of TVET and the irrelevance of school learning with enterprise work practices (Wu et. al., 2019). Finally, TVET in the Philippines over the years has gone a long way towards helping address access to education for all. As managed by TESDA, millions of Filipinos have been provided technical-vocational skills for employment and/or self-employment, especially in the poor sector of society. TVET's goals, objectives, and program implementation, which needs further improvements, are clearly aligned and in pursuit of SDG #4 which is geared toward quality education