Do short brief (intro, body, conclu), (Just Few Notes), comprisinng the most important takeaways of this text. Thank you.

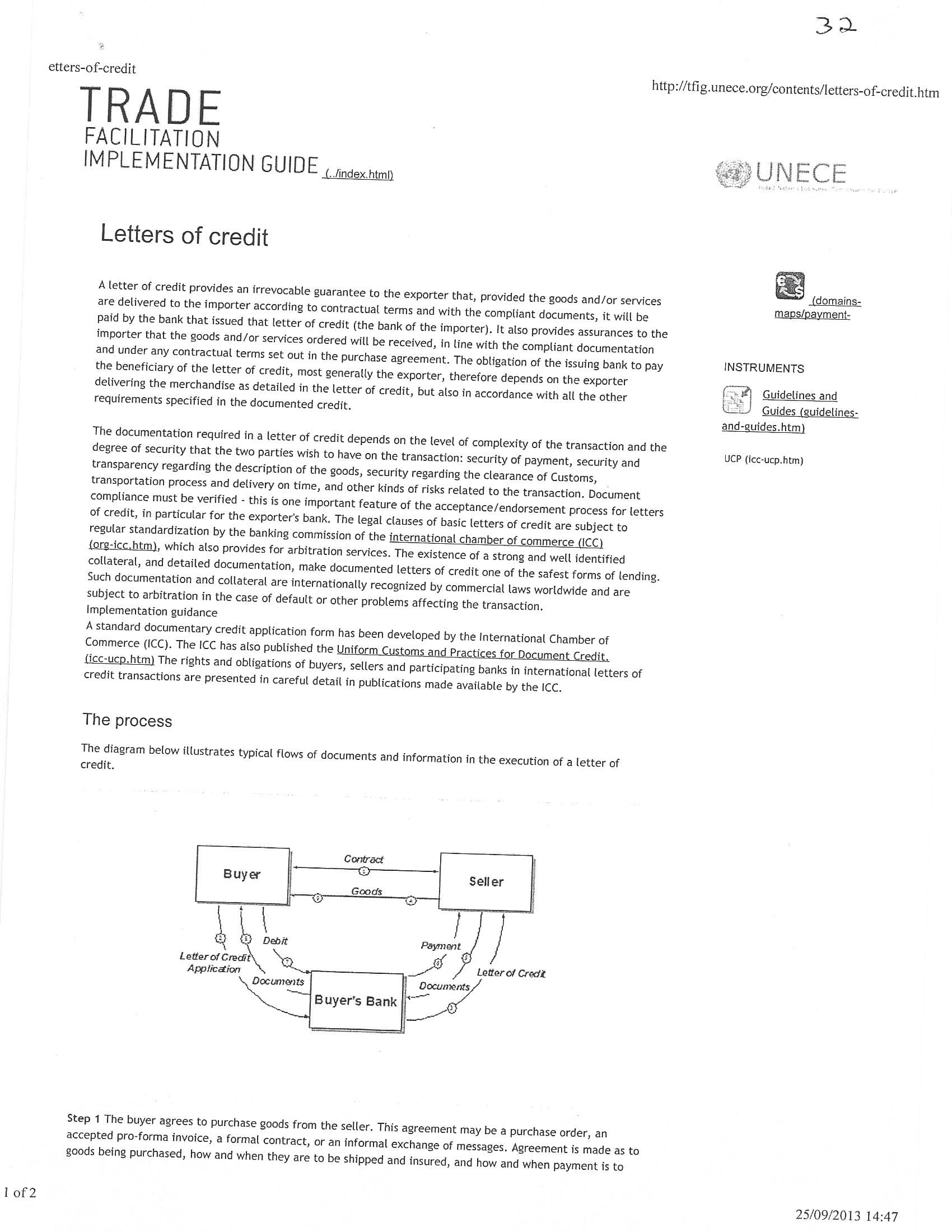

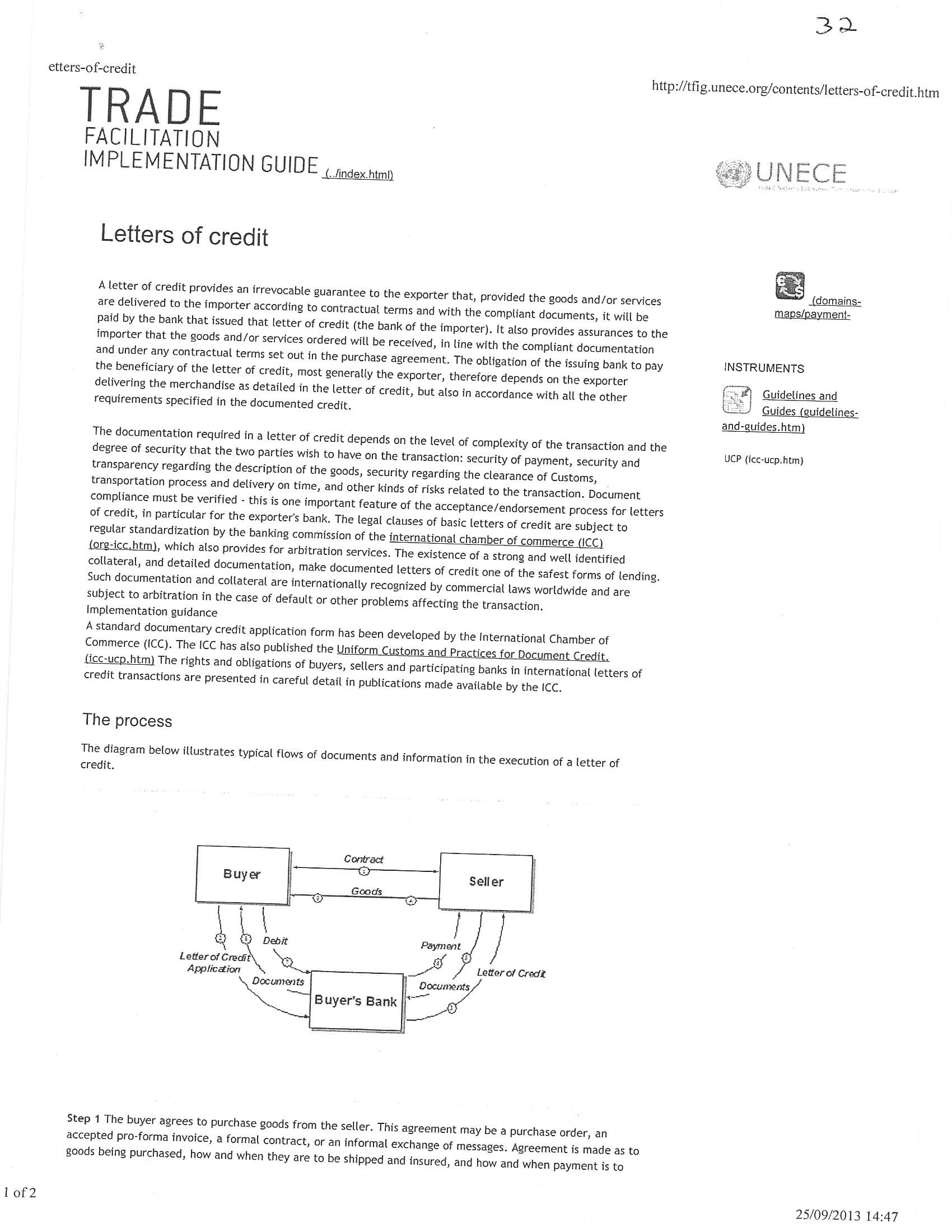

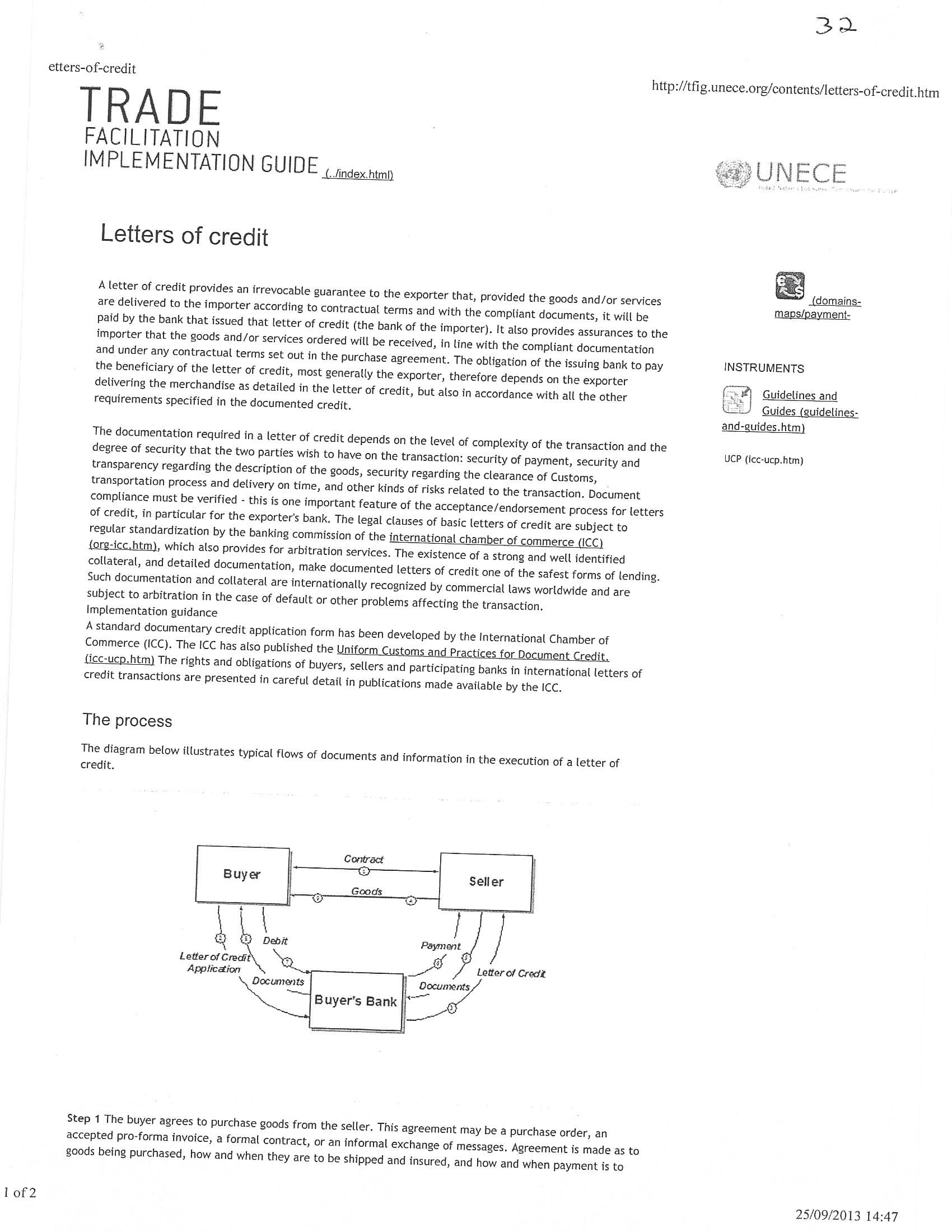

30 PART TWO: INTERNATIONAL SALES, CREDITS AND THE COMMERCIAL TRANSACTION AMERICAN BELL BACKGROUND AND FACTS INTERNATIONAL, pay the demand, Bell will imme- In 1978, American Bell Interna- INC. v. ISLAMIC diately become liable to Manu- tional, a subsidiary of AT&T, en- REPUBLIC OF IRAN facturers for $30.2 million, with tered into a contract with the 474 F.Supp. 420 (1979) no assurance of recouping those Imperial Government of Iran to United States District Court funds from Iran for the services provide consulting services and (S.D.N.Y) performed. While counsel repre- telecommunications equip- sented in graphic detail the ment. The contract provided other losses Bell faces at the that all disputes would be resolved according to the hands of the current Iranian government, these laws of Iran and in Iranian courts. The contract would flow regardless of whether we ordered the provided for payment to Bell of $280 million, in- relief sought. The hardship imposed from a denial cluding a down payment of $38 million. Iran had of relief is limited to the admittedly substantial the right to demand return of the down payment at sum of $30.2 million. any time and for any reason, with the amount re- But Manufacturers would face at least as great a turned to be reduced by 20 percent of the amounts loss, and perhaps a greater one, were we to grant that Bell had invoiced for work done. At the time of relief. Upon Manufacturers' failure to pay, Bank this action, about $30 million remained callable. In Iranshahr could initiate a suit on the Letter of order to secure the return of the down payment on Credit and attach $30.2 million of Manufacturers' demand, Bell had been required to arrange for assets in Iran. In addition, it could seek to hold Manufacturers Bank to issue a standby letter of Manufacturers liable for consequential damages credit to the Bank of Iranshahr, payable on the beyond that sum resulting from the failure to demand of the Iranian Government. However, in make timely payment. Finally, there is no guaran- 1979, a revolution resulted in the overthrow of the tee that Bank Iranshahr or the government, in imperial government. The Shah of Iran fled the retaliation for Manufacturers' recalcitrance, will country, and a revolutionary council was estab not nationalize additional Manufacturers' assets in lished to govern the country. The nation was in a Iran in amounts which counsel, at oral argument, state of chaos and westerners fled the country. Hav- represented to be far in excess of the amount in ing been left with unpaid invoices, Bell ceased its controversy here. operations. Fearing that any monies paid to Iran Apart from a greater monetary exposure flow- would never be recouped, Bell brought this action ing from an adverse decision, Manufacturers faces asking the court to enjoin Manufacturers Bank a loss of credibility in the international banking from honoring Iran's demands for payment under community that could result from its failure to the letter of credit. make good on a letter of credit. Bell, a sophisticated multinational enterprise MACMAHON, JUDGE well advised by competent counsel, entered into Plaintiff has failed to show that irreparable injury these arrangements with its corporate eyes open. may possibly ensue if a preliminary injunction is It knowingly and voluntarily signed a contract denied. Bell does not even claim, much less show, allowing the Iranian government to recoup its that it lacks an adequate remedy at law if Manu- down payment on demand, without regard to facturers makes a payment to Bank Iranshahr in cause. It caused Manufacturers to enter into an violation of the Letter of Credit. It is too clear for arrangement whereby Manufacturers became ob- argument that a suit for money damages could be ligated to pay Bank Iranshahr the unamortized based on any such violation, and surely Manufactoryayment balance upon receipt of conform- turers would be able to pay any money judgment ing documents, again without regard to cause. against it. . . . Both of these arrangements redounded tangibly To be sure, Bell faces substantial hardships to the benefit of Bell. The contract with Iran, with upon denial of its motion. Should Manufactureres (continued)3 1 Chapter Eight: Bank Collections, Trade Finance, and Letters of Credit (continued) its prospect of designing and installing from ers have been made the unwitting and innocent scratch a nationwide and international communi- victims of tumultuous events beyond their con- cations system, was certain to bring to Bell both trol. But, as between two innocents, the party who monetary profit and prestige and goodwill in the undertakes by contract the risk of political uncer- global communications industry. The agreement tainty and governmental caprice must bear the to indemnify Manufactures on its Letter of Credit consequences when the risk comes home to roost. provided the means by which these benefits could So ordered. be achieved. One who reaps the rewards of com- mercial arrangements must also accept their bur- Decision. The court refused to issue the injunc- dens. One such burden in this case, voluntarily tion. The letter of credit was not enjoined because accepted by Bell, was the risk that demand might there was no clear showing of irreparable injury he made without cause on the funds constituting and because the plaintiff had an adequate legal the down payment. To be sure, the sequence of remedy against Iran for the return of the monies events that led up to that demand may well have that would be paid. Such a rule protects the been unforeseeable when the contracts were sanctity of a bank's reputation for honoring its signed. To this extent, both Bell and Manufacture letters of credit. In KMW International v. Chase Manhattan quickly and with no view to actually using the Bank, 606 F.2d 10 (2d Cir. 1979), the court held goods themselves. They bear considerable risk that the unsettled situation in Iran was insuffi every day. Traders operate on little capital, cient reason for releasing the bank from its ob- buying merchandise or commodities in one ligation under a letter of credit. The court in country, taking title through the documents, KMW gave perhaps the real reason for the deci- and, then, through their business contacts built sion in the Iranian cases when it stated, "Both in up over years of experience, selling at a profit. the international business community and in Some traders specialize in trade with the devel- Iran itself, Chase's commercial honor is essen- oping world, often trading commodities for raw tially at stake. Failure to perform on its irrevoc materials or merchandise when dollars or hard cable letter of credit would constitute a breach of currency is not available there. For instance, a trust and substantially injure its reputation and Swiss bank issues a letter of credit for the perhaps even American credibility in foreign account of an African country in favor of the communities. Moreover, it could subject Chase trader, with a part of the credit transferred to to litigation in connection with not only this the trader's supplier in the Philippines for the matter, but also other banking affairs in Iran." cost of the goods it is supplying to the African country. This letter of credit can be split up Other Specialized Uses for Letters between many suppliers around the world, each of Credit presenting documents for payment, with the trader taking its profit out of the balance of the Many specialized types of letters of credit pro- credit. Shipments of crude oil are often bought vide a mechanism for financing a sale or other and sold in this fashion. business transaction. Some of these types are discussed here. Red Clauses in Credits. The red clause is a financing tool for smaller sellers who need capi- tal to produce the products to be shipped under Transferable Credits. Transferable credits a letter of credit. A red clause in a letter of are usually used by international traders. Trad- ers buy and sell goods in international trade- credit is a promise by the issuing bank to reimburse the seller's bank for loans made to32 etters-of-credit http://tfig.unece.org/contents/letters-of-credit.htm TRADE FACILITATION IMPLEMENTATION GUIDE ( /index.html) JUNECE Letters of credit A letter of credit provides an irrevocable guarantee to the exporter that, provided the goods and/or services (domains- are delivered to the importer according to contractual terms and with the compliant documents, it will be maps/payment- paid by the bank that issued that letter of credit (the bank of the importer). It also provides assurances to the importer that the goods and/or services ordered will be received, in line with the compliant documentation and under any contractual terms set out in the purchase agreement. The obligation of the issuing bank to pay INSTRUMENTS the beneficiary of the letter of credit, most generally the exporter, therefore depends on the exporter delivering the merchandise as detailed in the letter of credit, but also in accordance with all the other Guidelines and requirements specified in the documented credit. Guides (guidelines- and-guides.htm) The documentation required in a letter of credit depends on the level of complexity of the transaction and the degree of security that the two parties wish to have on the transaction: security of payment, security and UCP (icc-ucp.htm) transparency regarding the description of the goods, security regarding the clearance of Customs, transportation process and delivery on time, and other kinds of risks related to the transaction. Document compliance must be verified - this is one important feature of the acceptance/endorsement process for letters of credit, in particular for the exporter's bank. The legal clauses of basic letters of credit are subject to regular standardization by the banking commission of the international chamber of commerce (ICC) (org-icc.htm), which also provides for arbitration services. The existence of a strong and well identified collateral, and detailed documentation, make documented letters of credit one of the safest forms of lending. Such documentation and collateral are internationally recognized by commercial laws worldwide and are subject to arbitration in the case of default or other problems affecting the transaction. Implementation guidance A standard documentary credit application form has been developed by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). The ICC has also published the Uniform Customs and Practices for Document Credit. (icc-ucp.htm) The rights and obligations of buyers, sellers and participating banks in international letters of credit transactions are presented in careful detail in publications made available by the ICC. The process The diagram below illustrates typical flows of documents and information in the execution of a letter of credit. Contract Buyer Seller Goods Payment Letter of Credit Application Letter of Credit Documents Documents Buyer's Bank Step 1 The buyer agrees to purchase goods from the seller. This agreement may be a purchase order, an accepted pro-forma invoice, a formal contract, or an informal exchange of messages. Agreement is made as to goods being purchased, how and when they are to be shipped and insured, and how and when payment is to 1 of 2 25/09/2013 14:47Frigaliment Importing Co. v. B.N.S. International Sales Corp. United States District Court, S,D.N.Y., 1960' 190 ESupp. 116. I MEMLY, CIRCUIT JUDGE.a The issue is, What is chicken? Plaintiff says \"chicken\" means a young chicken, suitable for hroiling and flying. Defen- e. Commas are sometimes effective, sometimes not. Consult Overhauser v. United States, 45 F.3d 1085, 1086~87 (7th Cir.1995), rejecting the assumptions "that there is a clear rule of grammar by which the scope of a qualifying phrase can be determined from the placement of commas\" and \"that the agree- ment was drafted by a grammar-3.11 or at least by someone knowledgeable about ob- scure rules of grammar.\" Judge Posner pointed out that even the United States Su preme Court \"cannot make up its mind whether to be skeptical or credulous about imputing grammatical expertise to drafters of legal documents and using the imputation to decide interpretive questions.\" :1. Henry J. Friendly (19031986) clerked for Brandeis and then' practiced law in New York for thirty years before becoming a judge, and later chief judge, on the United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit. He was admired for his keen mind and the breadth of his learning. He advocated a dras- tic priming of the diversity jurisdiction of federal courts but would have retained juris diction over suits between aliens and United States citizens (as in the principal case) ow- ing to their "possible effect on international relations." H, Friendly, Federal Jurisdiction: A General View 150 n. 42 (1973). b. In the 1940's, American chicken pro~ ducers began to differentiate chickens raised for meat from those raised for eggs, and started using \"assembly-line\" techniques for the former, giving rise to a new consumer product, the \"broiler chicken." Production grew phenomenally, prices dropped corre 3?? SECTION 2 INTERPRETATION or CONTRACT 575 dant says \"chicken\" means any bird of that genus that meets contract specications on weight and quality, including what it calls \"stewing chicken\" and plaintiff pejoratively terms \"fowl.\" Dictionaries give both meanings, as well as some others not relevant here. To support its, plaintiff sends a number of volleys over the net; defendant essays to return them ' _ and adds a few serves of its own. Assuming that both parties were acting in ill be ' good faith, the case nicely illustrates Holines' remark \"that the making of a 'lQW contract depends not on the agreement of two minds in one intention, but on the agreement of two sets of external signsnot on the parties' having meant the same thing but on their having said the same thing.\" The Path iness of the Law, in Collected Legal Papers, p. 178. I have concluded that _ . plaintiff has not sustained its burden of persuasion that the contract used 'ng \"chicken\" in the narrower sense. The action is for breach of the warranty that goods sold shall corre- : spend to the description, New York Personal Property Law, McKinney's 7,: , _ ConsolLaws, c. 41, 95. Two contracts are in suit. In the rst, dated May ,2?\" 2, 1957, defendant, a New York sales corporation, conrmed the sale to 1 plaintiff, a Swiss corporation, of \"US Fresh Frozen Chicken,\" Grade A, Government Inspected, cted? ' Eviscerated ' 3.10]? Tit3 lbs. and lit2 lbs. each 1 butt all chicken individually wrapped in cryovac, packed in secured stat? ber cartons or wooden boxes, suitable for export ' ?Pf-' 9 75,000 lbs. 21753 lbs. ................................. $33.00 25,000 lbs. litZ lbs. ................................. $36.50 per 100 lbs. FAS New Yorlic \"scheduled May 10, 1957 pursuant to instructions from Penson 82; (30., New York.\" The second contract, also dated May 2, 1957, was identical save that only 50,000 lbs. of the heavier \"chicken\" were called for, the price of the smaller birds was $37 per 100 lbs, and shipment was scheduled for May 30. The says } initial shipment under the first contract was short but the balance was 5.; sfen- shipped on May 17. When the initial shipment arrived in Switzerland, r _ plaintiff found, on May 28, that the ZhS lbs. birds were not young chicken 1:11:61: suitable for broiling and frying but stewing chicken or \"fowl\"; indeed, 1 the many of the cartons and bags plainly so indicated. Protests ensued. N ever- draS- theless, shipment under the second contract was made on May 29, the Tit3 331\": lbs. birds again being stewing chicken. Defendant stopped the transporta- fnited tion of these at Rotterdam. 3012i This action followed. Plaintiff says that, notwithstanding that its acceptance was in Switzerland, New York law controls under the principle ction: i 3 pro\" r; spondingly, and exports to Europe increased c. RAE. is a common trade term that raised 33 sharply. Between 1956 and 1962, German means, in this context, that for the stated ' and ,2 chicken consumption went from 136 million price the seller will place the chicken \"free as for % P0131135 (0f Will-Ch 2:5 million 01" 1% was PX\" alongside\" a ship at the named port, here sinner % ported from the Umted States) to 716 million New York. lotion , pounds (of which 169.6 milhon or 26% was some :3 exported from the United. States). 55 38 576 CHAPTER 6 FINDING THE LAW OF THE CONTRACT of Rubin v. Irving Trust Co., 1953, 305 N.Y. 288, 305, 113 N.E.2d 424, 431; He defendant does not dispute this, and relies on New York decisions. I shall is follow the apparent agreement of the parties as to the applicable law. the "th Since the word "chicken" standing alone is ambiguous, I turn first to un: see whether the contract itself offers any aid to its interpretation. Plaintiff the says the 132-2 1bs. birds necessarily had to be young chicken since the older agr birds do not come in that size, hence the 212-3 lbs. birds must likewise be young. This is unpersuasive-a contract for "apples" of two different sizes could be filled with different kinds of apples even though only one species the came in both sizes. Defendant notes that the contract called not simply for Yor chicken but for "US Fresh Frozen Chicken, Grade A, Government Inspect- WOl ed." It says the contract thereby incorporated by reference the Department ny of Agriculture's regulations, which favor its interpretation; I shall return to wit this after reviewing plaintiff's other contentions. tha the The first hinges on an exchange of cablegrams which preceded execu- V . tion of the formal contracts. The negotiations leading up to the contracts "W were conducted in New York between defendant's secretary, Ernest R. Wij Bauer, and a Mr. Stovicek, who was in New York for the Czechoslovak Col government at the World Trade Fair. A few days after meeting Bauer at Wi the fair, Stovicek telephoned and inquired whether defendant would be all interested in exporting poultry to Switzerland. Bauer then met with low Stovicek, who showed him a cable from plaintiff dated April 26, 1957, chi announcing that they "are buyer" of 25,000 lbs. of chicken 212-3 lbs. the weight, Cryovac packed, grade A Government inspected, at a price up to 33 a cents per pound, for shipment on May 10, to be confirmed by the following da morning, and were interested in further offerings. After testing the market fry for price, Bauer accepted, and Stovicek sent a confirmation that evening. of Plaintiff stresses that, although these and subsequent cables between CO] plaintiff and defendant, which laid the basis for the additional quantities as under the first and for all of the second contract, were predominantly in en German, they used the English word "chicken"; it claims this was done on because it understood "chicken" meant young chicken whereas the Ger- "c man word, "Huhn," included both "Brathuhn" (broilers) and "Suppen- pli huhn" (stewing chicken), and that defendant, whose officers were thor- Co oughly conversant with German, should have realized this. Whatever force pc this argument might otherwise have is largely drained away by Bauer's di testimony that he asked Stovicek what kind of chickens were wanted, ot received the answer "any kind of chickens," and then, in German, asked whether the cable meant "Huhn" and received an affirmative re- cc sponse . .. . Plaintiff's next contention is that there was a definite trade usage that "chicken" meant "young chicken." Defendant showed that it was only di beginning in the poultry trade in 1957, thereby bringing itself within the hi principle that "when one of the parties is not a member of the trade or W other circle, his acceptance of the standard must be made to appear" by V : proving either that he had actual knowledge of the usage or that the usage is "so generally known in the community that his actual individual knowl- edge of it may be inferred." 9 Wigmore, Evidence (3d ed. 1940) $ 2464.new SECTION 2 INTERPRETATION or CONTRACT 577 1- Here there was no proof of actual knowledge of the alleged usage; indeed, it 111 is quite plain that defendant's belief was tothe contrary. In order to meet w. the alternative requirement, the law of New York demands a showing that to \"the usage is of so long continuance, so well established, so notorious, so iff universal and so reasonable in itself, as that the presumption is violent that er the parties contracted with reference to it, and made it a part of their be agreement.\" Walls v. Bailey, 1872, 4'9 NY. 464, 472473. es Plaintiff endeavored to establish such a usage by the testimony of .es three witnesses and certain other evidence. Strasser, resident buyer in New 'or York for a large chain of Swiss cooperatives, testied that \"on chicken I 3 _ would denitely understand a broiler.\" However, the force of this testimo- nt ny was considerably weakened by the fact that in his own transactions the to witness, a careful businessman, protected himself by using \"broiler\" when that was what he wanted and \"fowl\" when he wished older birds. Indeed, there are some indications, dating back to a remark of Lord Manseld, Edie 115' v. East hidia Co., 2 Burr. 1216, 1222 (1761), that no credit should be given \"witnesses to usage, who could not adduce instances in verication.\" 7 Wigrnore, Evidence (3d ed. 1940) 1954; see McDonald v. Acker, Merrall &. Condit Co., 2d Dept.1920, 192 AppDiv. 123, 125, 182 N.Y.S. 607. While Wigmore thinks this goes too far, a witness' consistent failure to rely on the alleged usage deprives his opinion testimony of much of its effect. Niesie lowski, an ofcer of one of the companies that had furnished the stevving chicken to defendant, testied that \"chicken\" meant \"the male species of the poultry industry. That could be a broiler, a fryer or a roaster,\" but not a stewing chicken; however, he also testied that upon receiving defen- g dent's inquiry for \"chickens,\" he asked whether the desire was for \"fowl or cat frying chickens\" and, in fact, supplied fowl, although taking the precaution 1g. of asking defendant, ,a day or two after plaintiff's acceptance of the en contracts in suit, to change its confirmation of its order from \"chickens,\" 1'88 as defendant had originally prepared it, to \"stewing chickens.\" Dates, an in employee of Urner~Barry Company, which publishes a daily market report He on the poultry trade, gave it as his view that the trade meaning of er- \"chicken\" was \"broilers and fryers.\" In addition to this opinion testimony, Ell- plaintiff relied on the fact that the UrnerBarry service, the Journal of or- Commerce, and Weinberg Bros. & Co. of Chicago, a large supplier of :ce poultry, published quotations in a manner which, in one way or another, 'r's distinguish between \"chicken,\" comprising broilers, fryers and certain ed, other categories, and \"fowl,\" which, Bauer acknowledged, included stewing :ed chickens. This material would be impressive if there were nothing to the re- contrary. However, there was, as will now be seen. Defendant's witness Weininger, who operates a chicken eviscerating Tat plant in New Jersey, testified \"Chicken is everything except a goose, a :y duck, and a turkey. Everything is a chicken, but then you have to say, you ;he have to specify which category you want or that you are talking about.\" Its or. witness Fox said that in the trade \"chicken\" would encompass all the by various classications. Sadina, who conducts a food inspection service, age testified that he would consider any bird coming within the classes of W1- \"chicken\" in the Department of Agriculture's regulations to be a chicken. 64. The specications approved by the General Services Administration include 578 CHAPTER 6 FINDING THE LAW OF THE CONTRACT fowl as well as broilers and fryers under the classification "chickens." shi Statistics of the Institute of American Poultry Industries use the phrases er "Young chickens" and "Mature chickens," under the general heading me "Total chickens." and the Department of Agriculture's daily and weekly 29 price reports avoid use of the word "chicken" without specification. not Defendant advances several other points which it claims affirmatively is t support its construction. Primary among these is the regulation of the to Department of Agriculture, 7 C.F.R. $$ 70.300-70.370, entitled, "Grading we and Inspection of Poultry and Edible Products Thereof." and in particular cost ent. $ 70.301 which recited: uno Chickens. The following are the various classes of chickens: bro: (a) Broiler or fryer ... clea (b) Roaster . .. that (c) Capon . .. and high (d) Stag ... lish (e) Hen or stewing chicken or fowl . .. broi (f) Cock or old rooster . Eur dani Defendant argues, as previously noted, that the contract incorporated these bird regulations by reference. Plaintiff answers that the contract provision only related simply to grade and Government inspection and did not incorporate opec the Government definition of "chicken," and also that the definition in the in th Regulations is ignored in the trade. However, the latter contention was contradicted by Weininger and Sadina; and there is force in defendant's coul argument that the contract made the regulations a dictionary, particularly 1bs. since the reference to Government grading was already in plaintiff's initial not cable to Stovicek. with Defendant makes a further argument based on the impossibility of its of A obtaining broilers and fryers at the 33 cents price offered by plaintiff for refer the 212-3 lbs. birds. There is no substantial dispute that, in late April, 1957, mark the price for 212-3 lbs. broilers was between 35 and 37 cents per pound, and be ec that when defendant entered into the contracts, it was well aware of this and and intended to fill them by supplying fowl in these weights. It claims that price plaintiff must likewise have known the market since plaintiff had reserved it is shipping space on April 23, three days before plaintiff's cable to Stovicek, show or, at least, that Stovicek was chargeable with such knowledge. It is broad scarcely an answer to say, as plaintiff does in its brief, that the 33 cents price offered for the 212-3 1bs. "chickens" was closer to the prevailing 35 law. . cents price for broilers than to the 30 cents at which defendant procured fowl. Plaintiff must have expected defendant to make some profit-certain- NOT. ly it could not have expected defendant deliberately to incur a loss. (] Finally, defendant relies on conduct by the plaintiff after the first chicke shipment had been received. On May 28 plaintiff sent two cables complain- "nicel ing that the larger birds in the first shipment constituted "fowl." Defen- on the thing. dant answered with a cable refusing to recognize plaintiff's objection and announcing "We have today ready for shipment 50,000 lbs. chicken 212-3 lbs. 25,000 lbs. broilers 12-2 lbs.," these being the goods procured for P.2d 1:SECTION 2 INTERPRETATION OF CONTRACT shipment under the second contract, and asked immediate answer "wheth ever we are to ship this merchandise to you and whether you will accept the merchandise. " After several other cable exchanges, plaintiff replied on May 29."Confirm again that merchandise is to be shipped since resold by us if not enough pursuant to contract chickens are shipped the missing quantity is to be shipped within ten days stop we resold to our customers pursuant to your contract chickens grade A you have to deliver us said merchandise we again state that we shall make you fully responsible for all resulting costs." Defendant argues that if plaintiff was sincere in thinking it was entitled to young chickens, plaintiff would not have-allowed the shipment under the second contract to go forward, since the distinction between broilers and chickens drawn in defendant's cablegram must have made it clear that the larger birds would not be broilers. However, plaintiff answers that the cables show plaintiff was insisting on delivery of young chickens and that defendant shipped old ones at its peril. Defendant's point would be highly relevant on another disputed issue-whether if liability were estab- lished, the measure of damages should be the difference in market value of broilers and stewing chicken in New York or the larger difference in Europe, but I cannot give it weight on the issue of interpretation. Defen- dant points out also that plaintiff proceeded to deliver some of the larger birds in Europe, describing them as "poulets"; defendant argues that it was only when plaintiff's customers complained about this that plaintiff devel- toped the idea that "chicken" meant "young chicken." There is little force in this in view of plaintiff's immediate and consistent protests. When all the evidence is reviewed, it is clear that defendant believed it could comply with the contracts by delivering stewing chicken in the 212-3 lbs. size. Defendant's subjective intent would not be significant if this did not coincide with an objective meaning of "chicken." Here it did coincide with one of the dictionary meanings, with the definition in the Department "of Agriculture Regulations to which the contract made at least oblique `reference, with at least some usage in the trade, with the realities of the market, and with what plaintiff's spokesman had said. Plaintiff asserts it to be equally plain that plaintiff's own subjective intent was to obtain broilers and fryers; the only evidence against this is the material as to market prices and this may not have been sufficiently brought home. In any event it is unnecessary to determine that issue. For plaintiff has the burden of showing that "chicken" was used in the narrower rather than in the broader sense, and this it has not sustained. This opinion constitutes the Court's findings of fact and conclusions of law. Judgment shall be entered dismissing the complaint with costs. NOTES (1) "What is Chicken"? Judge Friendly says that "The issue is, what is chicken?"c Is this the issue that the court had to decide? He also says that the case 'nicely illustrates Holmes' remark 'that the making of a contract depends ... not on the parties' having meant the same thing but on their having said the same thing.' " Does it? Would the result have been the same if both parties had meant c. See also Shrum v. Zeltwanger, 559 P.2d 1384 (Wyo.1977) ("What is a 'cow"?")