Question: EPS growth rate - 173, on calculator, example: for 1985-1990, press 5 N 100 +I- (to make it negative) PV 106 FV 0 PMT CPT

- EPS growth rate - 173, on calculator, example: for 1985-1990, press 5 N 100 +I- (to make it negative) PV 106 FV 0 PMT CPT I/Y (answer = 1.17% EPS growth rate), also compute 1990-1995 and 1995-2000,

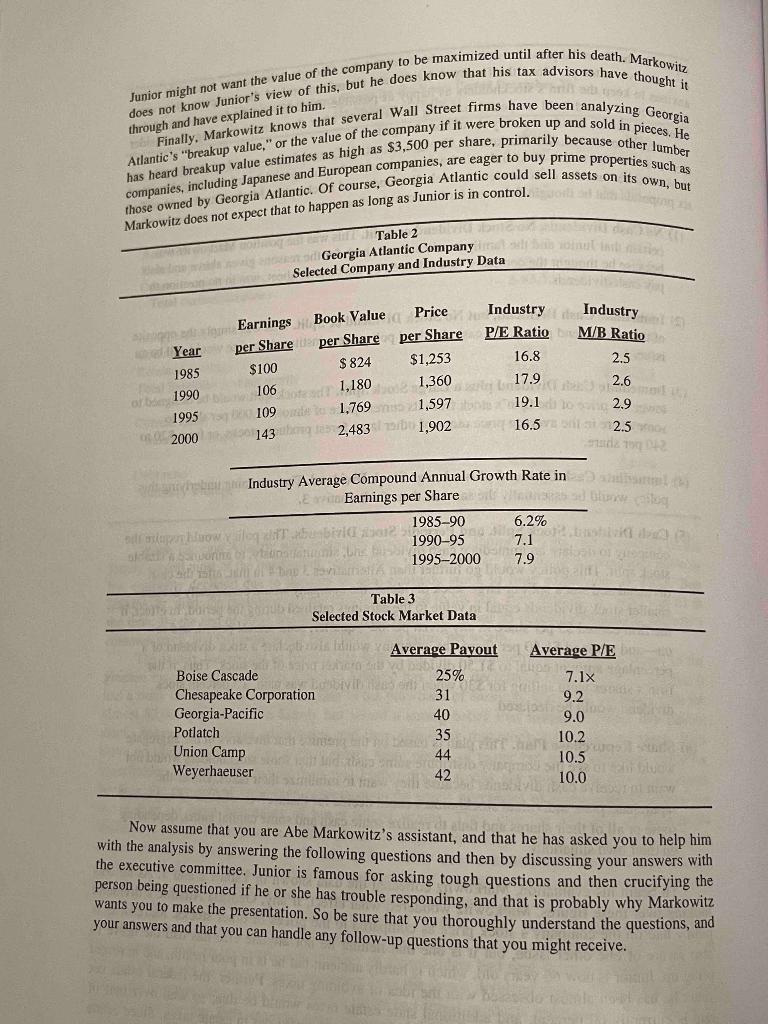

market/book ratio 124-5 example: for 1985, 1253 / 824 = 1.5, also compute 1990, 1995,and 2000

P/E 124 example: for 1985, 1253 / 100 = 12.5, also compute 1990, 1995,and 2000

3. Example: for 15 years earnings per share growth for Georgia Atlantic, press on calculator, 15 N 100 +I- PV 143 FV 0 PMT CPT I/Y (answer = 2.41%). Industry average = about 7% (see Table 2).

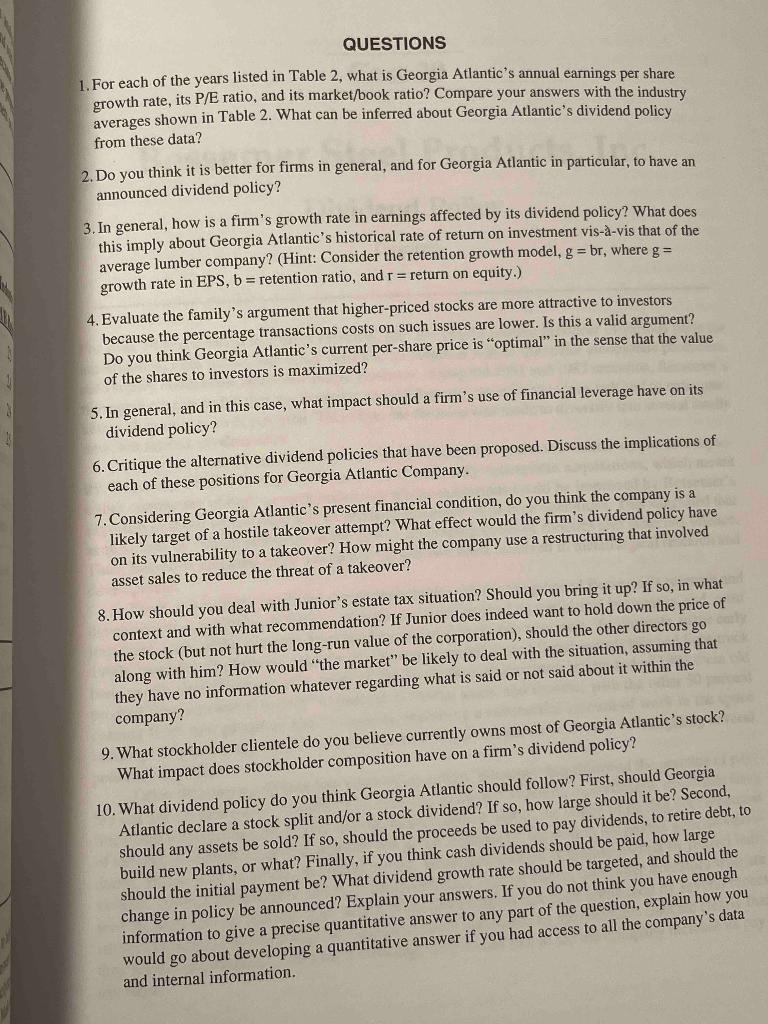

Please answer the first 5 questions on the last picture.

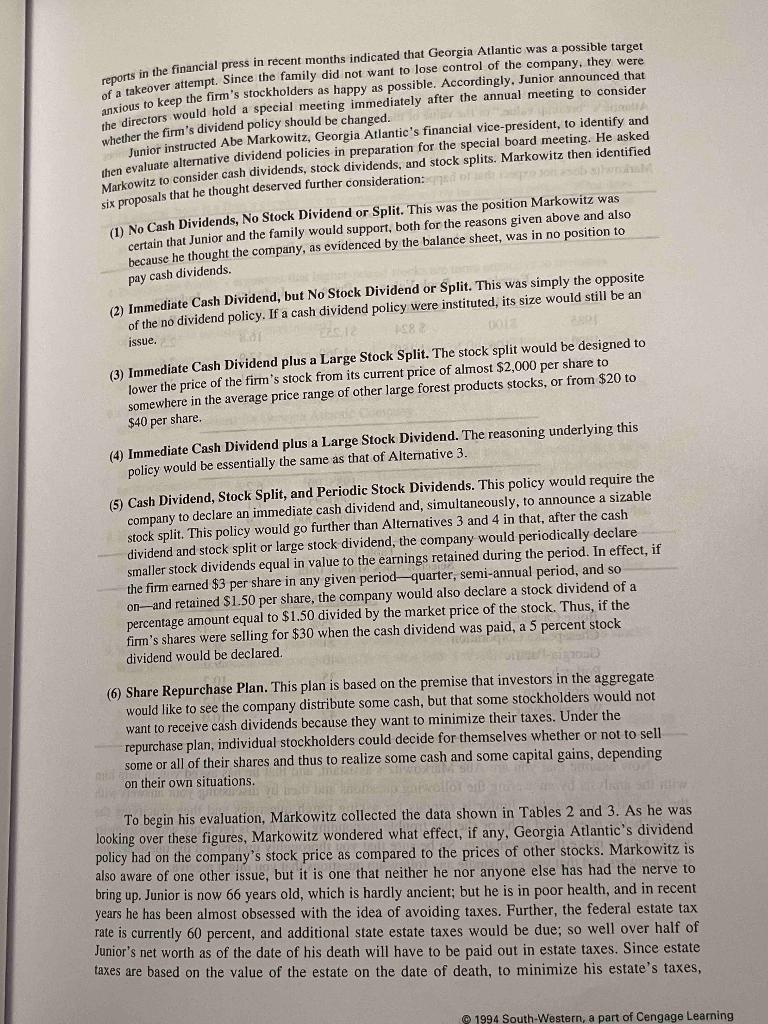

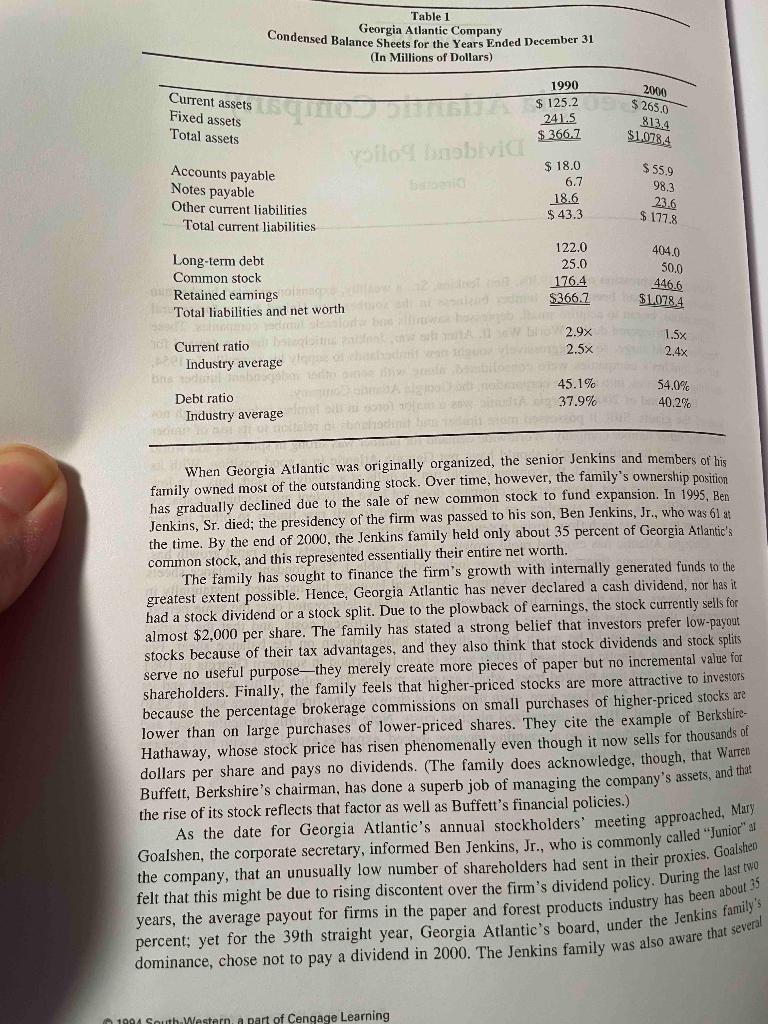

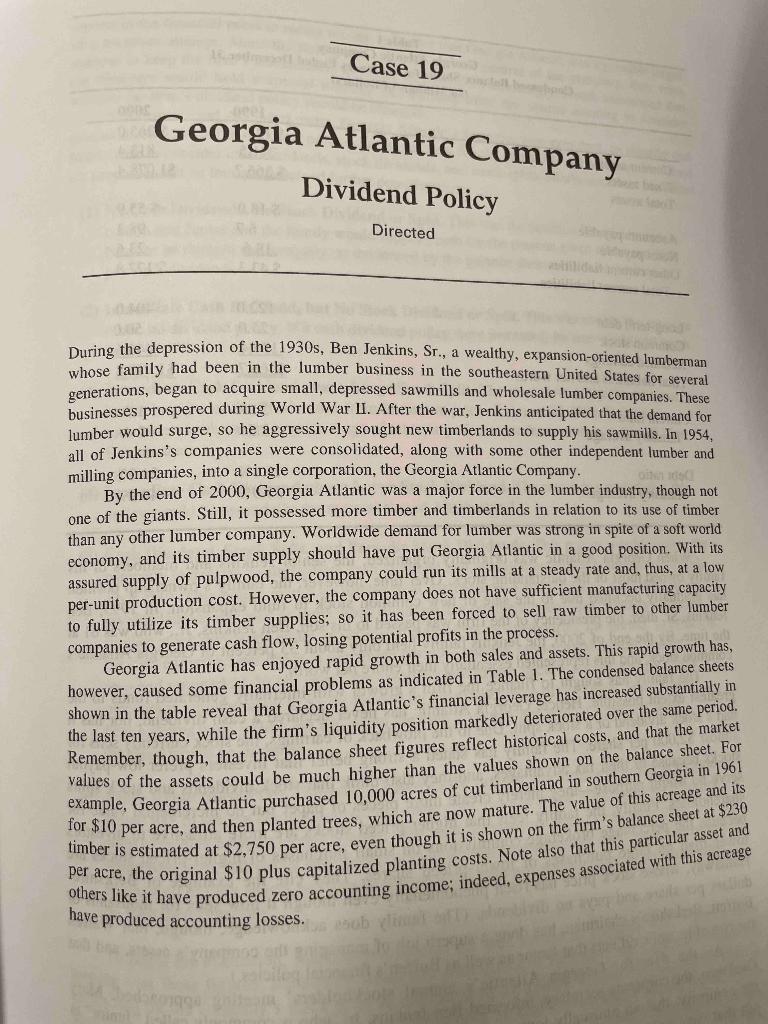

reports in the financial press in recent months indicated that Georgia Atlantic was a possible target anxious to keep the firm's stockholders as happy as possible. Accordingly, Junior announced that the directors would hold a special meeting immediately after the annual meeting to consider whether the firm's dividend policy should be changed. Junior instructed Abe Markowitz, Georgia Atlantic's financial vice-president, to identify and then evaluate alternative dividend policies in preparation for the special board meeting. He asked Markowitz to consider cash dividends, stock dividends, and stock splits. Markowitz then identified sit proposals that he thought deserved further consideration: (1) No Cash Dividends, No Stock Dividend or Split. This was the position Markowitz was certain that Junior and the family would support, both for the reasons given above and also because he thought the company, as evidenced by the balance sheet, was in no position to pay cash dividends. (2) Immediate Cash Dividend, but No Stock Dividend or Split. This was simply the opposite of the no dividend policy. If a cash dividend policy were instituted, its size would still be an issue. 18 00 (3) Immediate Cash Dividend plus a Large Stock Split. The stock split would be designed to lower the price of the firm's stock from its current price of almost $2,000 per share to somewhere in the average price range of other large forest products stocks, or from $20 to $40 per share. (4) Immediate Cash Dividend plus a Large Stock Dividend. The reasoning underlying this policy would be essentially the same as that of Alternative 3. (5) Cash Dividend, Stock Split, and Periodic Stock Dividends. This policy would require the company to declare an immediate cash dividend and, simultaneously, to announce a sizable stock split. This policy would go further than Alternatives 3 and 4 in that, after the cash dividend and stock split or large stock dividend, the company would periodically declare smaller stock dividends equal in value to the earnings retained during the period. In effect, if the firm earned $3 per share in any given period quarter, semi-annual period, and so onand retained $1.50 per share, the company would also declare a stock dividend of a percentage amount equal to $1.50 divided by the market price of the stock. Thus, if the firm's shares were selling for $30 when the cash dividend was paid, a 5 percent stock dividend would be declared. (6) Share Repurchase Plan. This plan is based on the premise that investors in the aggregate would like to see the company distribute some cash, but that some stockholders would not want to receive cash dividends because they want to minimize their taxes. Under the repurchase plan, individual stockholders could decide for themselves whether or not to sell some or all of their shares and thus to realize some cash and some capital gains, depending on their own situations. To begin his evaluation, Markowitz collected the data shown in Tables 2 and 3. As he was looking over these figures, Markowitz wondered what effect, if any, Georgia Atlantic's dividend policy had on the company's stock price as compared to the prices of other stocks. Markowitz is also aware of one other issue, but it is one that neither he nor anyone else has had the nerve to bring up. Junior is now 66 years old, which is hardly ancient; but he is in poor health, and in recent years he has been almost obsessed with the idea of avoiding taxes. Further, the federal estate tax rate is currently 60 percent, and additional state estate taxes would be due; so well over half of Junior's net worth as of the date of his death will have to be paid out in estate taxes. Since estate taxes are based on the value of the estate on the date of death, to minimize his estate's taxes, 1994 South-Western, a part of Cengage Learning at his tax ac ac through and have explained it to him. does not know Junior's view of this, but he does know that his tax advisors have thought it Junior might not want the value of the company to be maximized until after his death. Markowitz Atlantic's "breakup value," or the value of the company if it were broken up and sold in pieces. He Finally, Markowitz knows that several Wall Street firms have been analyzing Georgia has heard breakup value estimates as high as $3,500 per share, primarily because other lumber those owned by Georgia Atlantic. Of course, Georgia Atlantic could sell assets on its own, but companies, including Japanese and European companies, are eager to buy prime properties such as Markowitz does not expect that to happen as long as Junior is in control. MO Table 2 Georgia Atlantic Company Selected Company and Industry Data Year 1985 or 1990 Industry Industry P/E Ratio M/B Ratio 16.8 2.5 2.6 1995109 to 1,769 1,597 19.12.9 2000 1432,4831,90216.5 2.5 70 Earnings Book Value Price per Share per Share per Share $100 $ 824 $1,253 106 1,180 1,360 17.9 he Industry Average Compound Annual Growth Rate in staat e Earnings per Share on 1985-90 6.2% Dowlod 1990-95 7.1 1995-2000 7.9 stok Table 3 Selected Stock Market Data Average Payout Boise Cascade Chesapeake Corporation Georgia-Pacific Average P/E 7.1% 9.2 9.0 10.2 10.5 10.0 25% 31 40 35 44 42 Potlatch Union Camp Weyerhaeuser Now assume that you are Abe Markowitz's assistant, and that he has asked you to help him with the analysis by answering the following questions and then by discussing your answers with the executive committee. Junior is famous for asking tough questions and then crucifying the person being questioned if he or she has trouble responding, and that is probably why Markowitz wants you to make the presentation. So be sure that you thoroughly understand the questions, and your answers and that you can handle any follow-up questions that you might receive. Table 1 Georgia Atlantic Company Condensed Balance Sheets for the Years Ended December 31 (In Millions of Dollars) 1990 2000 $ 125.2 $265.0 Current assets Fixed assets Total assets $ique JOHASTA Wilo mobivia 241.5 $ 366.7 8134 $1.0784 Accounts payable Notes payable Other current liabilities Total current liabilities $ 18.0 6.7 18.6 $43.3 $55.9 98.3 23.6 $ 177.8 404.0 50.0 446.6 $1.078.4 Long-term debt 122.0 Common stock 25.0 176.4 Retained eamingsoon Total liabilities and net worth $366.7 2.9% Current ratio Industry average content on 2.5x bredbama Debt ratio SALO45.1% 37.9% Industry average 1.5x 2.4% 54.0% 40.29 When Georgia Atlantic was originally organized, the senior Jenkins and members of his farnily owned most of the outstanding stock. Over time, however, the family's ownership position has gradually declined due to the sale of new common stock to fund expansion. In 1995, Ben Jenkins, Sr. died; the presidency of the firm was passed to his son, Ben Jenkins, Jr., who was 61 the time. By the end of 2000, the Jenkins family held only about 35 percent of Georgia Atlantic's common stock, and this represented essentially their entire net worth. The family has sought to finance the firm's growth with internally generated funds to the greatest extent possible. Hence, Georgia Atlantic has never declared a cash dividend, nor has it had a stock dividend or a stock split. Due to the plowback of earnings, the stock currently sells for almost $2,000 per share. The family has stated a strong belief that investors prefer low-payout stocks because of their tax advantages, and they also think that stock dividends and stock splits serve no useful purposethey merely create more pieces of paper but no incremental value for shareholders. Finally, the family feels that higher-priced stocks are more attractive to investors because the percentage brokerage commissions on small purchases of higher-priced stocks are lower than on large purchases of lower-priced shares. They cite the example of Berkshire- Hathaway, whose stock price has risen phenomenally even though it now sells for thousands of dollars per share and pays no dividends. (The family does acknowledge, though, that Warren Buffett, Berkshire's chairman, has done a superb job of managing the company's assets, and that the rise of its stock reflects that factor as well as Buffett's financial policies.) As the date for Georgia Atlantic's annual stockholders' meeting approached, Mary Goalshen, the corporate secretary, informed Ben Jenkins, Jr., who is commonly called "Junior" the company, that an unusually low number of shareholders had sent in their proxies. Goalsheo felt that this might be due to rising discontent over the firm's dividend policy. During the last two years, the average payout for firms in the paper and forest products industry has been about 35 percent; yet for the 39th straight year, Georgia Atlantic's board, under the Jenkins family's dominance, chose not to pay a dividend in 2000. The Jenkins family was also aware that several 1994 South Western part of Cengage Learning Case 19 Georgia Atlantic Company Dividend Policy Directed During the depression of the 1930s, Ben Jenkins, Sr., a wealthy, expansion-oriented lumberman whose family had been in the lumber business in the southeastern United States for several generations, began to acquire small, depressed sawmills and wholesale lumber companies. These businesses prospered during World War II. After the war, Jenkins anticipated that the demand for lumber would surge, so he aggressively sought new timberlands to supply his sawmills. In 1954, all of Jenkins's companies were consolidated, along with some other independent lumber and milling companies, into a single corporation, the Georgia Atlantic Company. By the end of 2000, Georgia Atlantic was a major force in the lumber industry, though not one of the giants. Still, it possessed more timber and timberlands in relation to its use of timber than any other lumber company. Worldwide demand for lumber was strong in spite of a soft world economy, and its timber supply should have put Georgia Atlantic in a good position. With its assured supply of pulpwood, the company could run its mills at a steady rate and, thus, at a low per-unit production cost. However, the company does not have sufficient manufacturing capacity to fully utilize its timber supplies, so it has been forced to sell raw timber to other lumber companies to generate cash flow, losing potential profits in the process. Georgia Atlantic has enjoyed rapid growth in both sales and assets. This rapid growth has, however, caused some financial problems as indicated in Table 1. The condensed balance sheets shown in the table reveal that Georgia Atlantic's financial leverage has increased substantially in the last ten years, while the firm's liquidity position markedly deteriorated over the same period. Remember, though, that the balance sheet figures reflect historical costs, and that the market values of the assets could be much higher than the values shown on the balance sheet. For example, Georgia Atlantic purchased 10,000 acres of cut timberland in southern Georgia in 1961 for $10 per acre, and then planted trees, which are now mature. The value of this acreage and its timber is estimated at $2,750 per acre, even though it is shown on the firm's balance sheet at $230 per acre, the original $10 plus capitalized planting costs. Note also that this particular asset and others like it have produced zero accounting income; indeed, expenses associated with this acreage have produced accounting losses. QUESTIONS 1. For each of the years listed in Table 2, what is Georgia Atlantic's annual earnings per share growth rate, its P/E ratio, and its market/book ratio? Compare your answers with the industry averages shown in Table 2. What can be inferred about Georgia Atlantic's dividend policy from these data? 2. Do you think it is better for firms in general, and for Georgia Atlantic in particular, to have an announced dividend policy? 3. In general, how is a firm's growth rate in earnings affected by its dividend policy? What does this imply about Georgia Atlantic's historical rate of return on investment vis--vis that of the average lumber company? (Hint: Consider the retention growth model, g = br, where g = growth rate in EPS, b = retention ratio, and r = return on equity.) 4. Evaluate the family's argument that higher-priced stocks are more attractive to investors because the percentage transactions costs on such issues are lower. Is this a valid argument? Do you think Georgia Atlantic's current per-share price is "optimal" in the sense that the value of the shares to investors is maximized? 5. In general, and in this case, what impact should a firm's use of financial leverage have on its dividend policy? 6. Critique the alternative dividend policies that have been proposed. Discuss the implications of each of these positions for Georgia Atlantic Company. 7. Considering Georgia Atlantic's present financial condition, do you think the company is a likely target of a hostile takeover attempt? What effect would the firm's dividend policy have on its vulnerability to a takeover? How might the company use a restructuring that involved asset sales to reduce the threat of a takeover? 8. How should you deal with Junior's estate tax situation? Should you bring it up? If so, in what context and with what recommendation? If Junior does indeed want to hold down the price of the stock (but not hurt the long-run value of the corporation), should the other directors go along with him? How would "the market" be likely to deal with the situation, assuming that they have no information whatever regarding what is said or not said about it within the company? 9. What stockholder clientele do you believe currently owns most of Georgia Atlantic's stock? What impact does stockholder composition have on a firm's dividend policy? 10. What dividend policy do you think Georgia Atlantic should follow? First, should Georgia Atlantic declare a stock split and/or a stock dividend? If so, how large should it be? Second, should any assets be sold? If so, should the proceeds be used to pay dividends, to retire debt, to build new plants, or what? Finally, if you think cash dividends should be paid, how large should the initial payment be? What dividend growth rate should be targeted, and should the change in policy be announced? Explain your answers. If you do not think you have enough information to give a precise quantitative answer to any part of the question, explain how you would go about developing a quantitative answer if you had access to all the company's data and internal information. reports in the financial press in recent months indicated that Georgia Atlantic was a possible target anxious to keep the firm's stockholders as happy as possible. Accordingly, Junior announced that the directors would hold a special meeting immediately after the annual meeting to consider whether the firm's dividend policy should be changed. Junior instructed Abe Markowitz, Georgia Atlantic's financial vice-president, to identify and then evaluate alternative dividend policies in preparation for the special board meeting. He asked Markowitz to consider cash dividends, stock dividends, and stock splits. Markowitz then identified sit proposals that he thought deserved further consideration: (1) No Cash Dividends, No Stock Dividend or Split. This was the position Markowitz was certain that Junior and the family would support, both for the reasons given above and also because he thought the company, as evidenced by the balance sheet, was in no position to pay cash dividends. (2) Immediate Cash Dividend, but No Stock Dividend or Split. This was simply the opposite of the no dividend policy. If a cash dividend policy were instituted, its size would still be an issue. 18 00 (3) Immediate Cash Dividend plus a Large Stock Split. The stock split would be designed to lower the price of the firm's stock from its current price of almost $2,000 per share to somewhere in the average price range of other large forest products stocks, or from $20 to $40 per share. (4) Immediate Cash Dividend plus a Large Stock Dividend. The reasoning underlying this policy would be essentially the same as that of Alternative 3. (5) Cash Dividend, Stock Split, and Periodic Stock Dividends. This policy would require the company to declare an immediate cash dividend and, simultaneously, to announce a sizable stock split. This policy would go further than Alternatives 3 and 4 in that, after the cash dividend and stock split or large stock dividend, the company would periodically declare smaller stock dividends equal in value to the earnings retained during the period. In effect, if the firm earned $3 per share in any given period quarter, semi-annual period, and so onand retained $1.50 per share, the company would also declare a stock dividend of a percentage amount equal to $1.50 divided by the market price of the stock. Thus, if the firm's shares were selling for $30 when the cash dividend was paid, a 5 percent stock dividend would be declared. (6) Share Repurchase Plan. This plan is based on the premise that investors in the aggregate would like to see the company distribute some cash, but that some stockholders would not want to receive cash dividends because they want to minimize their taxes. Under the repurchase plan, individual stockholders could decide for themselves whether or not to sell some or all of their shares and thus to realize some cash and some capital gains, depending on their own situations. To begin his evaluation, Markowitz collected the data shown in Tables 2 and 3. As he was looking over these figures, Markowitz wondered what effect, if any, Georgia Atlantic's dividend policy had on the company's stock price as compared to the prices of other stocks. Markowitz is also aware of one other issue, but it is one that neither he nor anyone else has had the nerve to bring up. Junior is now 66 years old, which is hardly ancient; but he is in poor health, and in recent years he has been almost obsessed with the idea of avoiding taxes. Further, the federal estate tax rate is currently 60 percent, and additional state estate taxes would be due; so well over half of Junior's net worth as of the date of his death will have to be paid out in estate taxes. Since estate taxes are based on the value of the estate on the date of death, to minimize his estate's taxes, 1994 South-Western, a part of Cengage Learning at his tax ac ac through and have explained it to him. does not know Junior's view of this, but he does know that his tax advisors have thought it Junior might not want the value of the company to be maximized until after his death. Markowitz Atlantic's "breakup value," or the value of the company if it were broken up and sold in pieces. He Finally, Markowitz knows that several Wall Street firms have been analyzing Georgia has heard breakup value estimates as high as $3,500 per share, primarily because other lumber those owned by Georgia Atlantic. Of course, Georgia Atlantic could sell assets on its own, but companies, including Japanese and European companies, are eager to buy prime properties such as Markowitz does not expect that to happen as long as Junior is in control. MO Table 2 Georgia Atlantic Company Selected Company and Industry Data Year 1985 or 1990 Industry Industry P/E Ratio M/B Ratio 16.8 2.5 2.6 1995109 to 1,769 1,597 19.12.9 2000 1432,4831,90216.5 2.5 70 Earnings Book Value Price per Share per Share per Share $100 $ 824 $1,253 106 1,180 1,360 17.9 he Industry Average Compound Annual Growth Rate in staat e Earnings per Share on 1985-90 6.2% Dowlod 1990-95 7.1 1995-2000 7.9 stok Table 3 Selected Stock Market Data Average Payout Boise Cascade Chesapeake Corporation Georgia-Pacific Average P/E 7.1% 9.2 9.0 10.2 10.5 10.0 25% 31 40 35 44 42 Potlatch Union Camp Weyerhaeuser Now assume that you are Abe Markowitz's assistant, and that he has asked you to help him with the analysis by answering the following questions and then by discussing your answers with the executive committee. Junior is famous for asking tough questions and then crucifying the person being questioned if he or she has trouble responding, and that is probably why Markowitz wants you to make the presentation. So be sure that you thoroughly understand the questions, and your answers and that you can handle any follow-up questions that you might receive. Table 1 Georgia Atlantic Company Condensed Balance Sheets for the Years Ended December 31 (In Millions of Dollars) 1990 2000 $ 125.2 $265.0 Current assets Fixed assets Total assets $ique JOHASTA Wilo mobivia 241.5 $ 366.7 8134 $1.0784 Accounts payable Notes payable Other current liabilities Total current liabilities $ 18.0 6.7 18.6 $43.3 $55.9 98.3 23.6 $ 177.8 404.0 50.0 446.6 $1.078.4 Long-term debt 122.0 Common stock 25.0 176.4 Retained eamingsoon Total liabilities and net worth $366.7 2.9% Current ratio Industry average content on 2.5x bredbama Debt ratio SALO45.1% 37.9% Industry average 1.5x 2.4% 54.0% 40.29 When Georgia Atlantic was originally organized, the senior Jenkins and members of his farnily owned most of the outstanding stock. Over time, however, the family's ownership position has gradually declined due to the sale of new common stock to fund expansion. In 1995, Ben Jenkins, Sr. died; the presidency of the firm was passed to his son, Ben Jenkins, Jr., who was 61 the time. By the end of 2000, the Jenkins family held only about 35 percent of Georgia Atlantic's common stock, and this represented essentially their entire net worth. The family has sought to finance the firm's growth with internally generated funds to the greatest extent possible. Hence, Georgia Atlantic has never declared a cash dividend, nor has it had a stock dividend or a stock split. Due to the plowback of earnings, the stock currently sells for almost $2,000 per share. The family has stated a strong belief that investors prefer low-payout stocks because of their tax advantages, and they also think that stock dividends and stock splits serve no useful purposethey merely create more pieces of paper but no incremental value for shareholders. Finally, the family feels that higher-priced stocks are more attractive to investors because the percentage brokerage commissions on small purchases of higher-priced stocks are lower than on large purchases of lower-priced shares. They cite the example of Berkshire- Hathaway, whose stock price has risen phenomenally even though it now sells for thousands of dollars per share and pays no dividends. (The family does acknowledge, though, that Warren Buffett, Berkshire's chairman, has done a superb job of managing the company's assets, and that the rise of its stock reflects that factor as well as Buffett's financial policies.) As the date for Georgia Atlantic's annual stockholders' meeting approached, Mary Goalshen, the corporate secretary, informed Ben Jenkins, Jr., who is commonly called "Junior" the company, that an unusually low number of shareholders had sent in their proxies. Goalsheo felt that this might be due to rising discontent over the firm's dividend policy. During the last two years, the average payout for firms in the paper and forest products industry has been about 35 percent; yet for the 39th straight year, Georgia Atlantic's board, under the Jenkins family's dominance, chose not to pay a dividend in 2000. The Jenkins family was also aware that several 1994 South Western part of Cengage Learning Case 19 Georgia Atlantic Company Dividend Policy Directed During the depression of the 1930s, Ben Jenkins, Sr., a wealthy, expansion-oriented lumberman whose family had been in the lumber business in the southeastern United States for several generations, began to acquire small, depressed sawmills and wholesale lumber companies. These businesses prospered during World War II. After the war, Jenkins anticipated that the demand for lumber would surge, so he aggressively sought new timberlands to supply his sawmills. In 1954, all of Jenkins's companies were consolidated, along with some other independent lumber and milling companies, into a single corporation, the Georgia Atlantic Company. By the end of 2000, Georgia Atlantic was a major force in the lumber industry, though not one of the giants. Still, it possessed more timber and timberlands in relation to its use of timber than any other lumber company. Worldwide demand for lumber was strong in spite of a soft world economy, and its timber supply should have put Georgia Atlantic in a good position. With its assured supply of pulpwood, the company could run its mills at a steady rate and, thus, at a low per-unit production cost. However, the company does not have sufficient manufacturing capacity to fully utilize its timber supplies, so it has been forced to sell raw timber to other lumber companies to generate cash flow, losing potential profits in the process. Georgia Atlantic has enjoyed rapid growth in both sales and assets. This rapid growth has, however, caused some financial problems as indicated in Table 1. The condensed balance sheets shown in the table reveal that Georgia Atlantic's financial leverage has increased substantially in the last ten years, while the firm's liquidity position markedly deteriorated over the same period. Remember, though, that the balance sheet figures reflect historical costs, and that the market values of the assets could be much higher than the values shown on the balance sheet. For example, Georgia Atlantic purchased 10,000 acres of cut timberland in southern Georgia in 1961 for $10 per acre, and then planted trees, which are now mature. The value of this acreage and its timber is estimated at $2,750 per acre, even though it is shown on the firm's balance sheet at $230 per acre, the original $10 plus capitalized planting costs. Note also that this particular asset and others like it have produced zero accounting income; indeed, expenses associated with this acreage have produced accounting losses. QUESTIONS 1. For each of the years listed in Table 2, what is Georgia Atlantic's annual earnings per share growth rate, its P/E ratio, and its market/book ratio? Compare your answers with the industry averages shown in Table 2. What can be inferred about Georgia Atlantic's dividend policy from these data? 2. Do you think it is better for firms in general, and for Georgia Atlantic in particular, to have an announced dividend policy? 3. In general, how is a firm's growth rate in earnings affected by its dividend policy? What does this imply about Georgia Atlantic's historical rate of return on investment vis--vis that of the average lumber company? (Hint: Consider the retention growth model, g = br, where g = growth rate in EPS, b = retention ratio, and r = return on equity.) 4. Evaluate the family's argument that higher-priced stocks are more attractive to investors because the percentage transactions costs on such issues are lower. Is this a valid argument? Do you think Georgia Atlantic's current per-share price is "optimal" in the sense that the value of the shares to investors is maximized? 5. In general, and in this case, what impact should a firm's use of financial leverage have on its dividend policy? 6. Critique the alternative dividend policies that have been proposed. Discuss the implications of each of these positions for Georgia Atlantic Company. 7. Considering Georgia Atlantic's present financial condition, do you think the company is a likely target of a hostile takeover attempt? What effect would the firm's dividend policy have on its vulnerability to a takeover? How might the company use a restructuring that involved asset sales to reduce the threat of a takeover? 8. How should you deal with Junior's estate tax situation? Should you bring it up? If so, in what context and with what recommendation? If Junior does indeed want to hold down the price of the stock (but not hurt the long-run value of the corporation), should the other directors go along with him? How would "the market" be likely to deal with the situation, assuming that they have no information whatever regarding what is said or not said about it within the company? 9. What stockholder clientele do you believe currently owns most of Georgia Atlantic's stock? What impact does stockholder composition have on a firm's dividend policy? 10. What dividend policy do you think Georgia Atlantic should follow? First, should Georgia Atlantic declare a stock split and/or a stock dividend? If so, how large should it be? Second, should any assets be sold? If so, should the proceeds be used to pay dividends, to retire debt, to build new plants, or what? Finally, if you think cash dividends should be paid, how large should the initial payment be? What dividend growth rate should be targeted, and should the change in policy be announced? Explain your answers. If you do not think you have enough information to give a precise quantitative answer to any part of the question, explain how you would go about developing a quantitative answer if you had access to all the company's data and internal information

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts