Evaluate the following for the below-given case FAIRDEAL APPLIANCES: MANAGING THE DEALER NETWORK FOR

OPTIMAL SALES:

What do you make of Abul's decision and its implications for Abdul's risk?

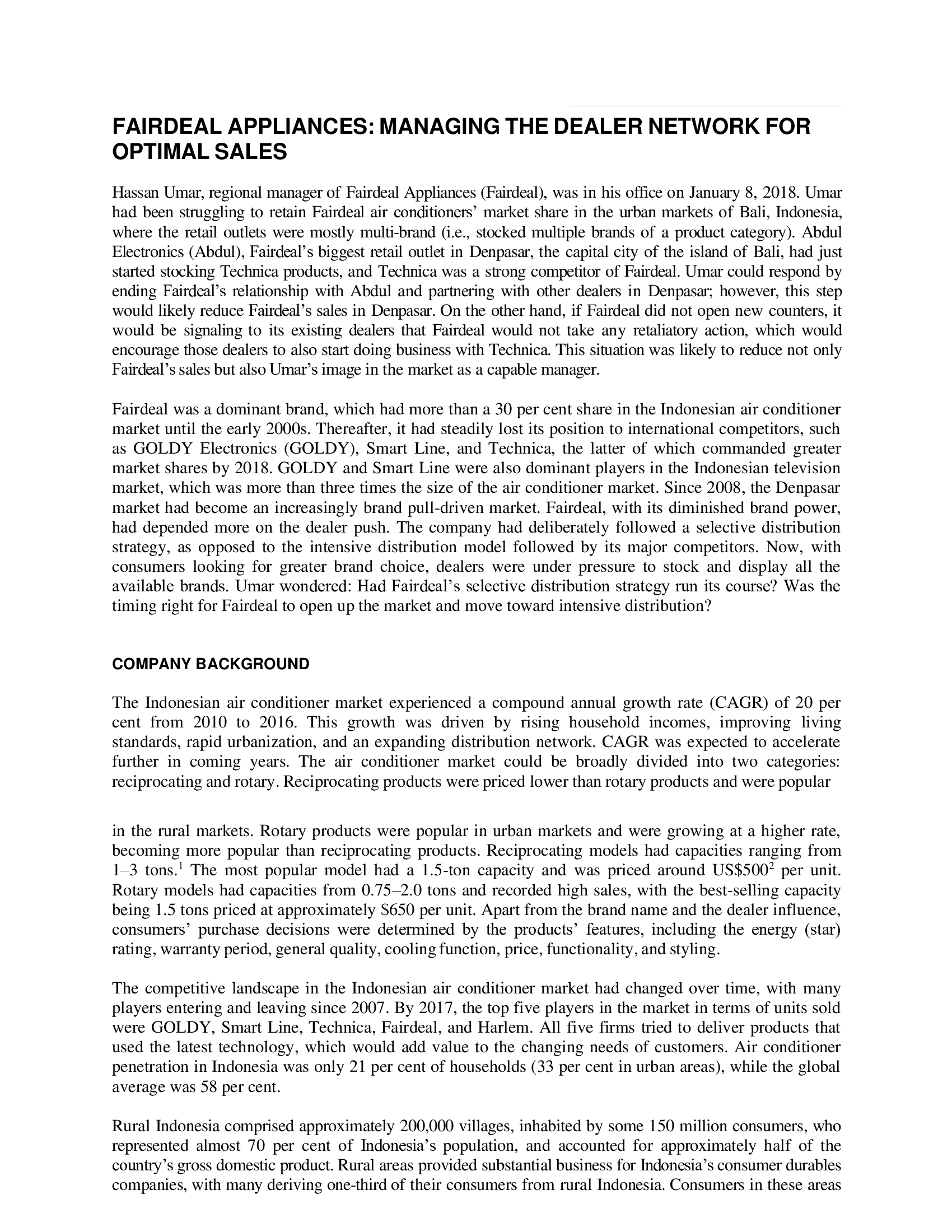

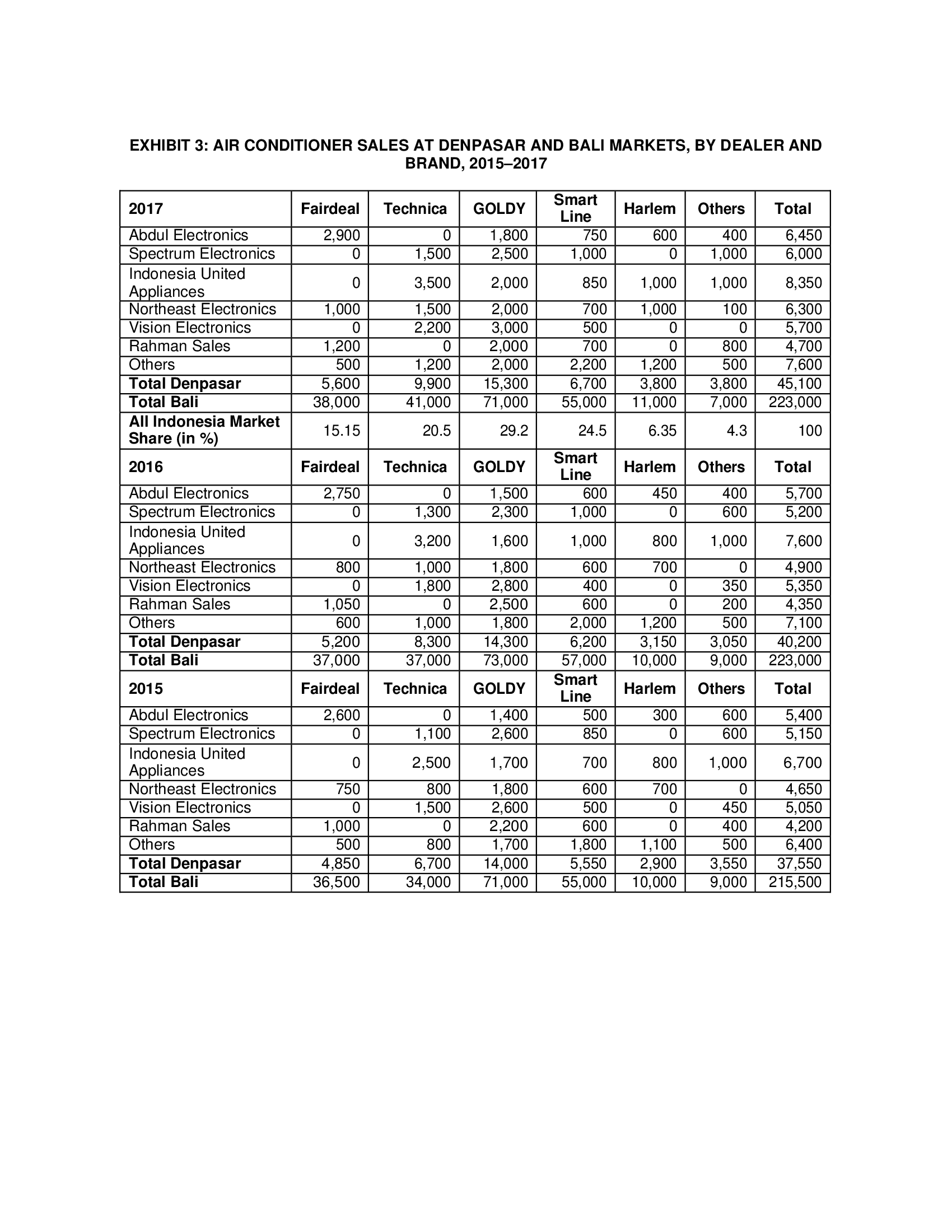

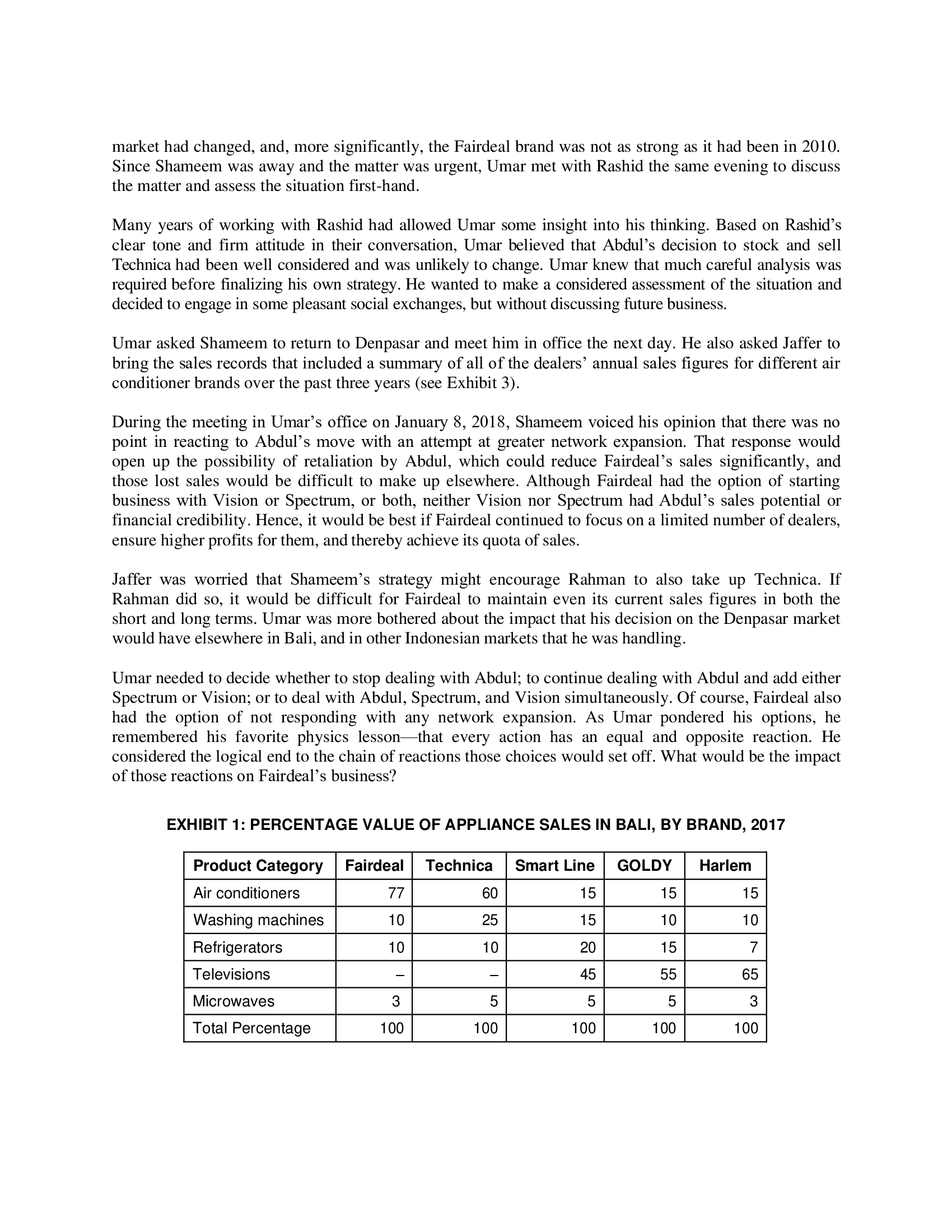

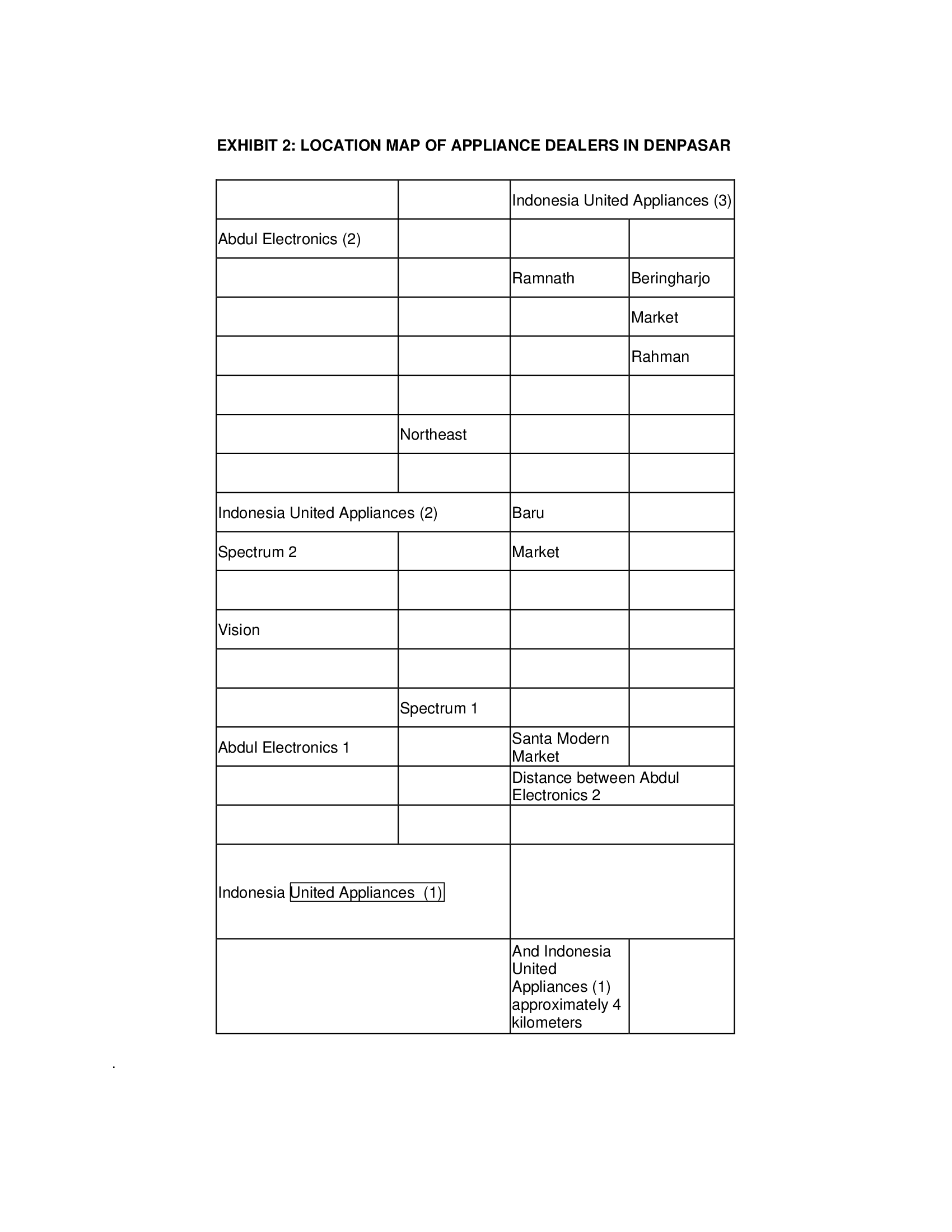

FAIRDEAL APPLIANCES: MANAGING THE DEALER NETWORK FOR OPTIMAL SALES Hassan Umar, regional manager of Fairdeal Appliances (Fairdeal), was in his ofce on January 8, 2018. Umar had been struggling to retain Fairdeal air oonditioners' market share in the urban markets of Bali, Indonesia, where the retail outlets were mostly multibr'and (i.e., stocked multiple brands of a product category). Abdul Electronics (Abdul), Fairdeal's biggest retail outlet in Denpasar, the capital city of the island of Bali, had just started stocking Technica products, and Technica was a strong competitor of Fairdeal. Umar could respond by ending Fairdeal's relationship with Abdul and partnering with other dealers in Denpasar; however, this step would likely reduce Fairdeal's sales in Denpasar. On the other hand, if Fairdeal did not open new counters, it would be signaling to its existing dealers that Fairdeal would not take any retaliatory action, which would encourage those dealers to also start doing business with Technica. This situation was likely to reduce not only Fairdeal's sales but also Umar's image in the market as a capable manager. Fairdeal was a dominant brand, which had more than a 30 per cent share in the Indonesian air conditioner market until the early 2000s. Thereafter, it had steadily lost its position to international competitors, such as GOLDY Electronics (GOLDY), Smart Line, and Technica, the latter of which commanded greater market shares by 2018. GOLDY and Smart Line were also dominant players in the Indonesian television market, which was more than three times the size of the air conditioner market. Since 2008, the Denpasar market had become an increasingly brand pull-driven market. Fairdeal, with its diminished brand power, had depended more on the dealer push. The company had deliberately followed a selective distribution strategy, as opposed to the intensive distribution model followed by its major competitors. Now, with consumers looking for greater brand choice, dealers were under pressure to stock and display all the available brands. Umar wondered: Had Fairdeal's selective distribution strategy run its course? Was the timing right for Fairdeal to open up the market and move toward intensive distribution? COMPANY BACKGROUND The Indonesian air conditioner market experienced a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 20 per cent from 2010 to 2016. This growth was driven by rising household incomes, improving living standards, rapid urbanization, and an expanding distribution network. CAGR was expected to accelerate further in coming years. The air conditioner market could be broadly divided into two categories: reciprocating and rotary. Reciprocating products were priced lower than rotary products and were popular in the rural markets. Rotary products were popular in urban markets and were growing at a higher rate, becoming more popular than reciprocating products. Reciprocating models had capacities ranging from 173 tons.1 The most popular model had a 1.5-ton capacity and was priced around US$5002 per unit. Rotary models had capacities from 0.75720 tons and recorded high sales, with the best-selling capacity being 1.5 tons priced at approximately $650 per unit. Apart from the brand name and the dealer inuence, consumers' purchase decisions were determined by the products' features, including the energy (star) rating, warranty period, general quality, cooling function, price, functionality, and styling. The competitive landscape in the Indonesian air conditioner market had changed over time, with many players entering and leaving since 2007. By 2017, the top ve players in the market in terms of units sold were GOLDY, Smart Line, Technica, Fairdeal, and Harlem. All ve rms tried to deliver products that used the latest technology, which would add value to the changing needs of customers. Air conditioner penetration in Indonesia was only 21 per cent of households (33 per cent in urban areas), while the global average was 58 per cent. Rural Indonesia comprised approximately 200,000 villages, inhabited by some 150 million consumers, who represented almost 70 per cent of Indonesia's population, and accounted for approximately half of the country's gross domestic product. Rural areas provided substantial business for Indonesia's consumer durables companies, with many deriving onethird of their consumers from rural Indonesia. Consumers in these areas \fhad different consumption patterns from consumers in the urban areas, but their preferences were gradually but denitely changing to resemble those of consumers in the urban areas. THE DENPASAR MARKET All of the largest air conditioner companies in Indonesia operated from branch offices in Denpasar. The branches were headed by branch managers, who supervised sales executives and commercial staff. Sales executives were responsible for delivering budgeted sales through the dealer and distributor network. Branches supplied products directly to their dealers and to distributors located in Denpasar and upcountry markets.3 Distributors typically supplied products to the smaller retailers. The major appliance dealers in Denpasar were Indonesia United Appliances (Induapp), Abdul, Vision Electronics (Vision), Spectrum Electronics (Spectrum), Northeast Electronics (Northeast), and Rahman Sales (Rahman). In addition, Denpasar had many smaller dealers, such as Taufiq Stores, Ramnath Traders, and Ibrahim Electronics, but they did not generate significant air conditioner sales. All of these dealers were multi-brand, multiproduct outlets that provided consumers with a one-stop solution for their appliance needs. In addition to selling air conditioners, they also sold televisions, washing machines, refrigerators, and microwaves. For these dealers, the air conditioner business accounted for, on average, 20 per cent of their turnover and 15 per cent of their profit (see Exhibit 1). The companies selling air conditioners also represented multiple product ranges. There was intense competition among the dealers, and price-cutting was common. The gross margin earned by the dealers varied between $20 and $30 per air conditioner sold. This variation in gross margin depended on the specic model being sold, the season, and the bargaining capability of the customer, apart from the dealer's sales target, turnover, and inventory level of the specic model of the product. Companies provided after-sales service to consumers directly, using a separate service franchisee network. The service departments of these appliance companies supervised these franchisees and reported to the branch manager, but operated independently of the sales function unless a specic issue arose with any dealer ordistn'butor. Retail appliance sales in Denpasar were concentrated in three main markets: Beringharjo (30 per cent), Earn (20 per cent), and Santa Modern (45 per cent). The remaining 5 per cent of sales were in smaller markets distributed across Denpasar. The Beringharjo outlet of Induapp contributed almost 32 per cent to Induapp's total annual air conditioner sales. In contrast, in the initial six months of operating a retail counter in Beringharjo, Abdul could generate only 25 per cent of its total monthly air conditioner sales from the Beringharjo outlet. APPLIANCE COMPANIES IN DENPASAR Fairdeal Appliances Fairdeal had set up its Denpasar branch operation in 1986. It had a stable workforce, which showed a rise in the attrition rate of its sales force from 2015 to 2018. The support staff looked after accounts, after sales service, and logistics, and had remained virtually unchanged since Fairdeal's inception. The company appointed its dealers and distributors carefully with the objective of creating a long-term business association. Fairdeal was not aggressive in terms of discounts, credit terms, or network expansion plans, but kept up with major changes in the market conditions. For the annual business tie-up with dealers, Fairdeal followed the nancial year (i.e., April 1 to March 31), while all other appliance companies followed the calendar year (i.e., January 1 to December 31). Fairdeal's air conditioner range was capable of meeting the product requirements of most customers (in terms of both price and product features). The brand was considered by consumers to be reliable but was not perceived as being trendy or high-technology (high-tech). Thus, in 2016, Fairdeal launched a new range of high-tech, energy-saving air conditioners named Fairdeal EDGE-DIGITAL and NEWEX. Both of these products were designed to meet the competition from multinational companies. Fairdeal invested heavily in a high-visibility, mass-media campaign throughout 2017, in an effort to give these products a modern and high-tech prole and generate sales. Technica Technica had set up its Denpasar branch operations in 1996. The company experienced high employee turnover. At Technica's Denpasar branch, employees in sales, service, and the commercial functions stayed with the company for an average of only 2.5 years. Technica's air conditioner range was competitive and consisted of a range of technologically advanced products named \"6th Sense Intelfresh\" and \"6th Sense Fast Cool.\" The brand enjoyed a positive and high- tech image. The channel partners also considered Technica to be a major multinational brand with a strong local presence in Bali. Technica had a large dealer base spread across Bali, and was the market leader in washing machines. The company was aggressive with discounts and with expanding its distribution network, and even offered generous credit terms on a selective basis to some strategically important dealers anddistributors. GOLDY Electronics GOLDY was a Korean multinational company whose slogan was \"Enjoy Life.\" Since 1998, GOLDY had consistently been Indonesia's fastest-growing brand in all appliance categories. The company had captured the Indonesian market essentially on the strength of its brand pull, its distribution presence, and its matchingproduct delivery. GOLDY started its Denpasar operations in 1997 and initially focused on the television and washing machine markets. In 1998, it expanded its portfolio to include microwave ovens, refrigerators, and air conditioners. GOLDY was aggressive in its distribution network expansion and discount payouts. The company exerted pressure on its dealers and distributors to achieve high sales volumes and was ready to support its dealers and distributors through local promotions. GOLDY products enjoyed high customer confidence. A major attraction for many appliance dealers was the customer attention and store trafc that the brand generated across its product portfolio. Smart Line Smart Line was a large Korean appliance retailer that was present in the Indonesian consumer goods market across such categories as mobile phones, televisions, refrigerators, and air conditioners. Smart Line set up its Bali operations in 1998. Its greatest strength was the strong demand for its televisions, washing machines, and refrigerators throughout its extensive distributor and dealer network. Smart Line did not initially focus on air conditioners, but from 2010 onward, it ensured that air conditioners were present in all its retail outlets, and Smart Line received a share of air conditioner sales from all of its outlets. Its full-line forcing strategy\" provided the company with good dividends. Harlem Harlem was a Shanghai-based Chinese company. Harlem Indonesia started in January 2004 as a 100 per cent subsidiary. The rm was known for introducing innovative products, including its revolutionary split air conditioners, which were rst launched in Indonesia. Harlem also offered a 10-year product guaranteeithe longest in the industryias well as a wide range of televisions, water heaters, air conditioners, wine cellars, washing machines, water heaters, and deep freezers. However, it had yet to rmly establish its brand image in Indonesia. The Harlem branch operation was set up in Bali in 2011, modelled after Fairdeal's branch operations. Yet unlike Fairdeal, Harlem sold only through distributors, which supplied dealers. Its sales force had direct interaction with some key dealers. The company had maintained a steady share in the market for the past few years. It leveraged its television sales and greater discounts to drive its air conditioner sales. KEY DEALERS IN THE DENPASAR MARKET Indonesia United Appliances (lnduapp) Induapp was a large retail chain in Eastern Indonesia and Denpasar's largest retailer in terms of appliance sales. It had three retail outlets strategically located in all three major markets in Denpasar (see Exhibit 2). The owner of Induapp, a management graduate from a reputed institute in Indonesia, ensured that the organization was professionally run. A central team located in Jakarta decided on which brands to stock. This team had often claimed that it did not nd Fairdeal's business terms to be attractive, It was unlikely that Induapp would deal with Fairdeal within the next two years. Induapp acquired new customers through innovative customer schemes that it regularly ran, at the regional level. Its promotions were supported by huge advertising budgets and were normally well accepted in the market. The company provided prompt and professional services, which helped it retain a loyal customer base. lnduapp's strength was marketing, and it also had tremendous nancial backing. Vision Electronics Vision had a showroom located in a prime location in the Santa Modern Market. It was a major seller of GOLDY and Technica air conditioners, and of televisions, washing machines, and refrigerators. Because of its location, Vision found itself in direct competition with Abdul and Induapp. Its more limited nancial clout forced it to undercut these competitors (i.e., sell its products at lower rates). Thus, the company operated on smaller margins and high turnover. However, it made up for its nancial limitations with its aggressive selling orientation, displays, and promotion of brands that did not compete with brands represented by Abdul and Induapp. Vision was often behind in its accounts payable. Hence, companies would not extend additional credit to Vision unless they were extremely hard pressed for sales. Although Vision did not have a clear case of bad debt, the sales team often required much follow-up to release payments. Northeast Electronics Northeast, located in Baru Market, was the premium appliance retailer in Denpasar. It had a wealthy and loyal client base. The company stocked all of the top brands in all product categories. It did not provide high sales volume to any of the brands but helped enhance the image of these brands in the Denpasar market. Northeast offered attractive displays and an enjoyable ambience in addition to giving customers the opportunity to negotiate prices. The company did not push any particular brand and sold at prices that were consistently higher than any other appliance retailer in Denpasar. Adequate sales support was available for consumers who wanted to know about product features and compare across brands. Northeast's customer base was less price sensitive than others and was typically looking for premium products. The rm's sales mix included the higherend models of the various product categories. Rahman Sales Established in 2001, Rahman was one of Denpasar's best-managed retailers. Its owners were two brothers, Hashim and Jalal. One of them was always present at the counter to provide personal attention to customers. The brothers gave tremendous importance to customer care and also offered lower prices compared with others in Beringharjo Market. Because of the company's customer-centric policies and competent sales team, it had developed a large and loyal client base. Rahman's owners were offended when Fairdeal opened a new dealership with MS Tauq, which was located nearby, in 2014. Rahman retaliated by shifting its focus away from Fairdeal; however, it did not \fAIR CONDITIONER BUSINESS TRADE PRACTICES Discounts All of the air conditioner manufacturers in Indonesia paid a standard cash discount of 577 per cent of the retail price to its dealers. Additional payment discounts were available in the range of 2 per cent for immediate payment to l per cent for payment within 15 days. The cash discount was an annual policy and did not change within the year for any of the companies. The manufacturers typically had an annual deal with every important dealer, which was in the range of $10 to $15 per unit on achievement of an agreed-upon target. The manufacturers also offered monthly schemes to manage temporary imbalances in their product mix or to counter targeted competitive actions. Monthly schemes usually depended on the volume of monthly purchases, and were typically in the range of $5 to $15 per unit, depending on volume of business, the specic models sold, and other similar factors. Because of the discount differentials, dealers tried to maximize their bonus earnings so that they could buy products at cheaper prices than the rest of the competition. The key to this strategy was being able to negotiate with a manufacturer's branch sales team, which had some level of exibility in giving higher monthly schemes to dealers on a casetocase basis. However, the ability to sell the additional products purchased in a scheme to retail consumers was important for realizing the real benefits of such schemes. Social Networks The respective owners of Rahman and Abdul were cousins who competed in the market, often for the same consumers, but also cooperated in terms of sharing stock in the case of a shortage. It was common knowledge in the trade circle that the cousins usually decided on which brands to support based on joint consultation. These two dealerships often followed each other's successrl strategies. Further, the owner of Northeast was a personal friend of the owners of Abdul and Rahman. Together, the owners of these three outlets formed an informal cartel to put pressure on manufacturers and other dealers in the market. The respective owners of Vision and Spectrum formed another team. They usually kept a low prole as dealers but were known to start the price competition in the market. In addition to having been classmates in school, they had become business friends because of the market situation; they needed to compete with the cartel of Abdul, Rahman, and Northeast on one side and the giant Induapp on the other. Although Induapp operated independently, its strengths were signicant: sound business strategy, nancial muscle, and marketing acumen. An undercurrent of competition existed between Induapp and the other appliance players in the Denpasar market, as every appliance rm aspired to become as successful as Induapp. Other players in the Denpasar appliance market were essentially independent businesses focusing on their individual prot maximization. They did not have much clout in the market to inuence company policies, and conducted their business without much fuss. Consumer and Channel Behavior Prospective air conditioner customers in Indonesia typically visited a retailer's counter and selected the brand and the model they wanted to buy. Then the price negotiations began. After knowing the best offer price from the retail counter, customers conducted a price comparison across other counters. For example, if 100 customers went to Beringharjo to buy an air conditioner from Rahman, 15 of them did not visit any other counter and purchased from Rahman after price negotiations; 60 customers went to other counters in Beringharjo and enquired about the price; and the balance of 25 customers went to counters in all the three markets (Beringharjo, Baru, and Santa Modern) before making their final purchase decision. The 85 customers who compared prices across counters usually bought from the dealer who had offered the lowest price for the model of theirchoice. The dealer's motivation to sell a particular brand of air conditioner was directly proportional to the margin the dealer would make. The margin was typically less if there was another nearby counter selling the same brand. If any dealer did not have a competitor in its vicinity, then it could be sure that the customer would not nd a better price on the specic brand; hence, the dealer could charge a higher price. The air conditioner business showed characteristics that were typical of the consumer durables segment, where dealers were able to inuence the brand preference of some customers at the point of sale. On average, dealers were able to convert 3540 per cent of their air conditioner customers to the brand of the dealer's choice. THE PROBLEM AT HAND In a repeat of the events in 2010, Abdul started stocking Technica products on January 6, 2018; however, this time, Abdul did not inform the Fairdeal team. When Ajmal J affer, the Fairdeal sales executive, visited the Abdul counter in Santa Modern Market on January 7, 2018, he found Technica's large sign board in front. When he went inside, he found a display of Technica products and noticed a distinct reduction in the display of products from Fairdeal and all other brands. Jaffer was not at all happy with this development and demanded to know the reason for taking up the Technica dealership. Rashid, who was working at the counter, coolly explained that Abdul was losing customers who wanted to see Technica air conditioners and washing machines for comparison. Since Abdul was not stocking Technica, it was losing not only the air conditioner sales but also the associated television, washing machine, and refrigerator sales that could have accrued from that customer. However, Rashid emphasized that Abdul would still meet the sales volume for the 201713 commitment to Fairdeal and, in any case, would sell Technica products only to customers who would not buy Fairdeal products. Rashid also shared his strong belief that stockng Technica products would lead to an increase in the counter's volume sales and Fairdeal would benet from this increased trafc. Yet, he made it clear that if Fairdeal wanted to reconsider any decision regarding its dealer network and its business with Abdul in future, then it was free to do so; Abdul would make its own decisions, which would be driven by its own business interests. J affer immediately called Umar to report this conversation. On Fairdeal's behalf, Umar had been dealing with Abdul in various capacities for more than 20 years. Umar's rst reaction was that this move would help Abdul grow bigger as an air conditioner counter but at the same time, Abdul's air conditioner margins would be reduced. He also noted that the timing of this decision seemed highly strategic: if Umar did not take proper measures, Fairdeal might lose its share of sales from this counter in both the short and long terms. Because Abdul represented a large and prestigious selling counter for Fairdeal, any loss of share in this counter could send the wrong signal in the market. From experience, Umar knew that if Fairdeal decided to take a rm stance and sever ties with Abdul, it could create greater obstacles to success in the future. He wanted to take a considered approach because whatever happened in the Denpasar market would indirectly affect the rest of Bali and the nearby islands. Umar had been actively involved as Fairdeal's branch manager when Fairdeal managed to change Abdul's decision about taking on the Technica dealership in 2010. Now, Umar was unsure how the current Fairdeal branch manager, Asim Shameem, would see the situation. The power dynamics in the \f\f