Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Executive Function You have probably noticed that a key component of cognitive development in middle childhood is the increasing ability to control and monitor

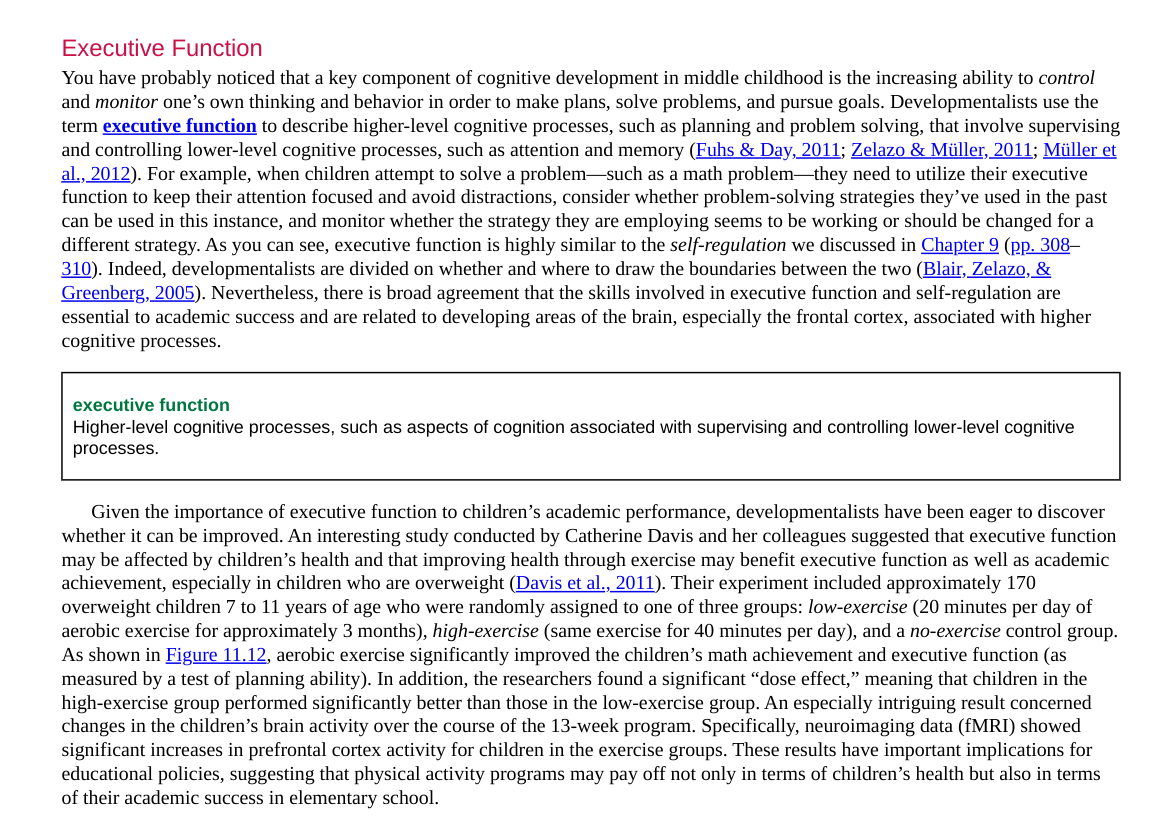

Executive Function You have probably noticed that a key component of cognitive development in middle childhood is the increasing ability to control and monitor one's own thinking and behavior in order to make plans, solve problems, and pursue goals. Developmentalists use the term executive function to describe higher-level cognitive processes, such as planning and problem solving, that involve supervising and controlling lower-level cognitive processes, such as attention and memory (Fuhs & Day, 2011; Zelazo & Mller, 2011; Mller et al., 2012). For example, when children attempt to solve a problem-such as a math problem-they need to utilize their executive function to keep their attention focused and avoid distractions, consider whether problem-solving strategies they've used in the past can be used in this instance, and monitor whether the strategy they are employing seems to be working or should be changed for a different strategy. As you can see, executive function is highly similar to the self-regulation we discussed in Chapter 9 (pp. 308- 310). Indeed, developmentalists are divided on whether and where to draw the boundaries between the two (Blair, Zelazo, & Greenberg, 2005). Nevertheless, there is broad agreement that the skills involved in executive function and self-regulation are essential to academic success and are related to developing areas of the brain, especially the frontal cortex, associated with higher cognitive processes. executive function Higher-level cognitive processes, such as aspects of cognition associated with supervising and controlling lower-level cognitive processes. Given the importance of executive function to children's academic performance, developmentalists have been eager to discover whether it can be improved. An interesting study conducted by Catherine Davis and her colleagues suggested that executive function may be affected by children's health and that improving health through exercise may benefit executive function as well as academic achievement, especially in children who are overweight (Davis et al., 2011). Their experiment included approximately 170 overweight children 7 to 11 years of age who were randomly assigned to one of three groups: low-exercise (20 minutes per day of aerobic exercise for approximately 3 months), high-exercise (same exercise for 40 minutes per day), and a no-exercise control group. As shown in Figure 11.12, aerobic exercise significantly improved the children's math achievement and executive function (as measured by a test of planning ability). In addition, the researchers found a significant "dose effect," meaning that children in the high-exercise group performed significantly better than those in the low-exercise group. An especially intriguing result concerned changes in the children's brain activity over the course of the 13-week program. Specifically, neuroimaging data (fMRI) showed significant increases in prefrontal cortex activity for children in the exercise groups. These results have important implications for educational policies, suggesting that physical activity programs may pay off not only in terms of children's health but also in terms of their academic success in elementary school. A vast variety of biological and environmental factors are known to contribute to childhood overweight and obesity. In an effort to organize these factors into a "big picture," Kristen Harrison and her colleagues proposed the Six-Cs developmental ecological model (Harrison et al., 2011; Dev et al., 2013). As indicated in the following list, the six Cs range from the microscopic level of genes to the most general level of culture. Cell: Biological and genetic characteristics, such as the inheritance of genes that contribute to fat storage . Child: Behaviors, attitudes, and knowledge relevant to weight gain, including eating patterns, exercise, and the ability to control behavior (self-regulation) Clan: Family characteristics, such as parents' encouragement to exercise and eat healthy foods, family media use, and whether the child was fed breast or artificial milk during infancy Community: Factors in the local community, including school meal programs and vending-machine options, availability of grocery stores, and access to recreational activities Country: State and national characteristics such as government funding for nutrition programs, healthy-eating media campaigns, and state or federal dietary guidelines Culture: Cultural and social beliefs and practices, including gender-role expectations concerning eating and activity, cultural standards for beauty, and norms regarding portion sizes served in restaurants Given that the risk of childhood obesity resides at multiple levels, Harrison and her colleagues are not surprised that most intervention efforts to reduce overweight and obesity have been unsuccessful; they say that such efforts are narrowly focused at a single level. For example, one approach may target the child level by engaging children in physical activity programs, whereas another may target the community level by introducing healthier lunch menus at schools. Ecological models such as the Six-Cs underscore the importance of comprehensive interventions that tackle childhood overweight and obesity at multiple levels simultaneously. Motor Development Walking along the beach one day, we saw a girl about 7 years old and her little brother, who was about 4 years old, following their father and their older brother, who was 10 or 11 years old. The father and older brother were tossing a ball back and forth as they walked. The girl was hopping along the sand on one foot, and her younger brother scrambled to keep up with her. Suddenly the little girl threw her arms up in the air, leaned over, threw her feet up, and did a cartwheel. She then did another cartwheel. Her younger brother stopped to watch her. Then he tried one. He fell in a heap in the sand, and she continued doing one perfect cartwheel after another. In such everyday scenes, you can see the increases in motor development that occur over the course of middle childhood (see Figure 11.1, p. 376). Children become stronger and more agile, and their balance improves. They run faster; they throw balls farther and with greater efficiency and are more likely to catch them. They also jump farther and higher than they did when they were younger, and they learn to skate, ride bikes, dance, swim, and climb trees as well as acquire a host of other physical skills during this period.

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started