- Explain the process of balancing efficiency of cross-border integration with the responsiveness required by national differences in developing global product strategy.

- Explain the organizational implications of global strategic choices, including the implications for the assignment of roles and responsibilities to managers.

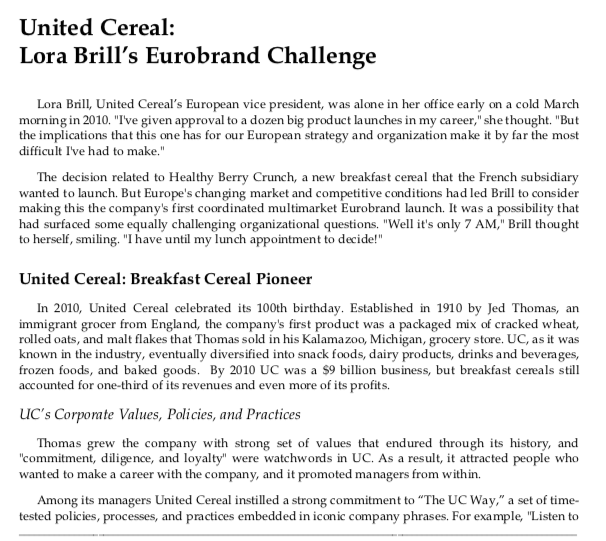

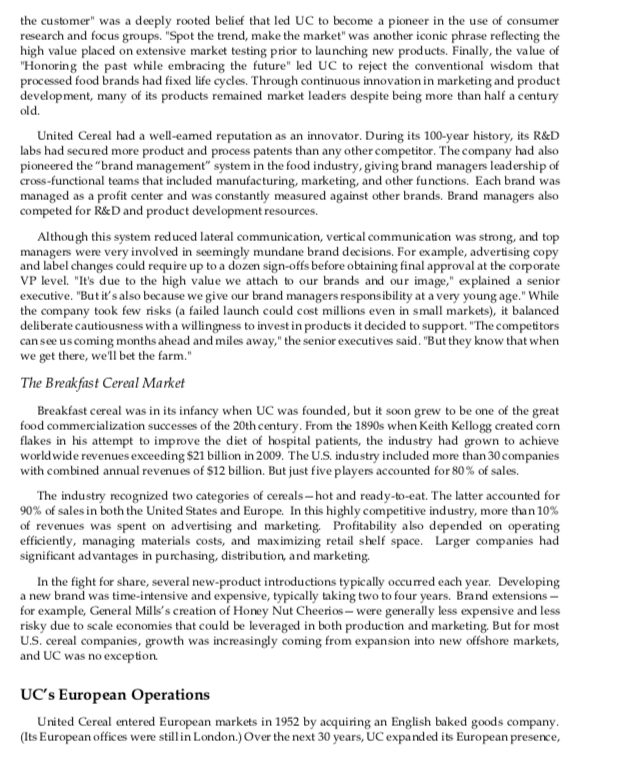

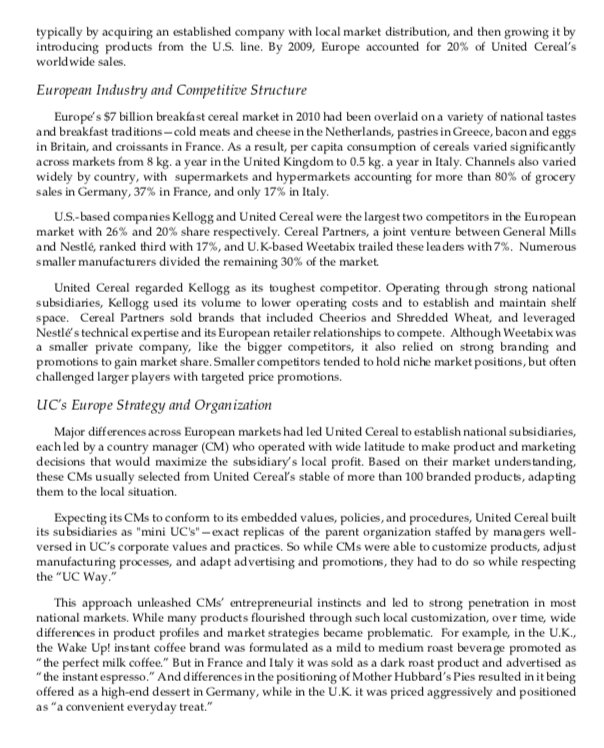

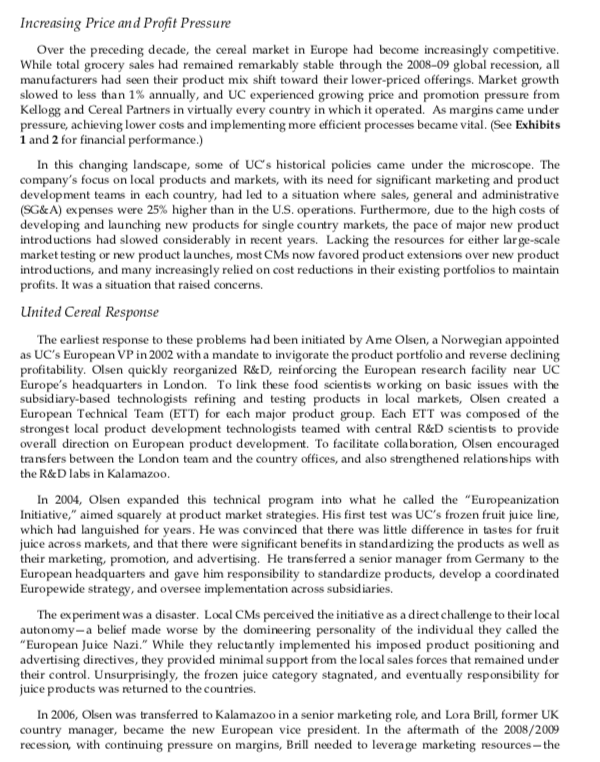

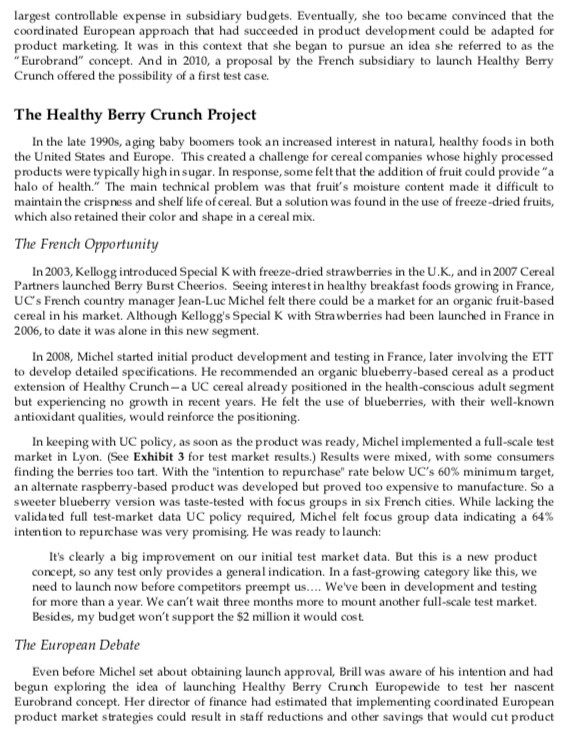

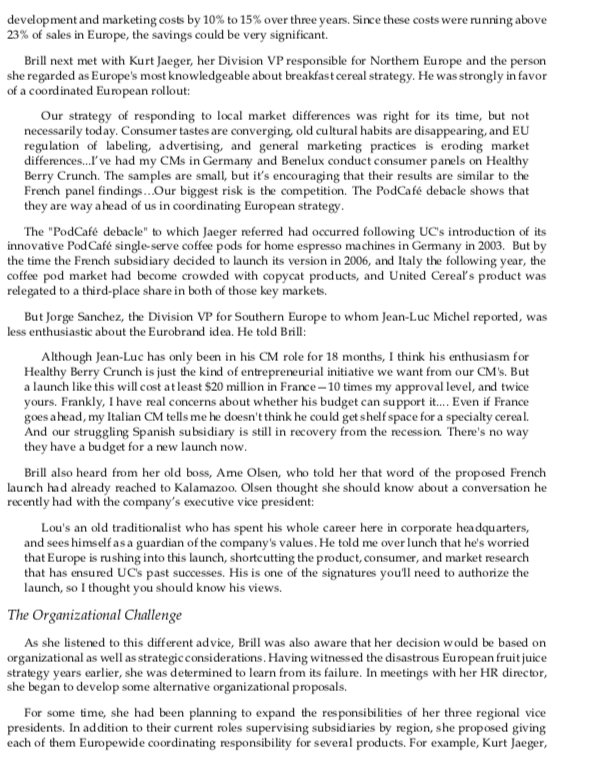

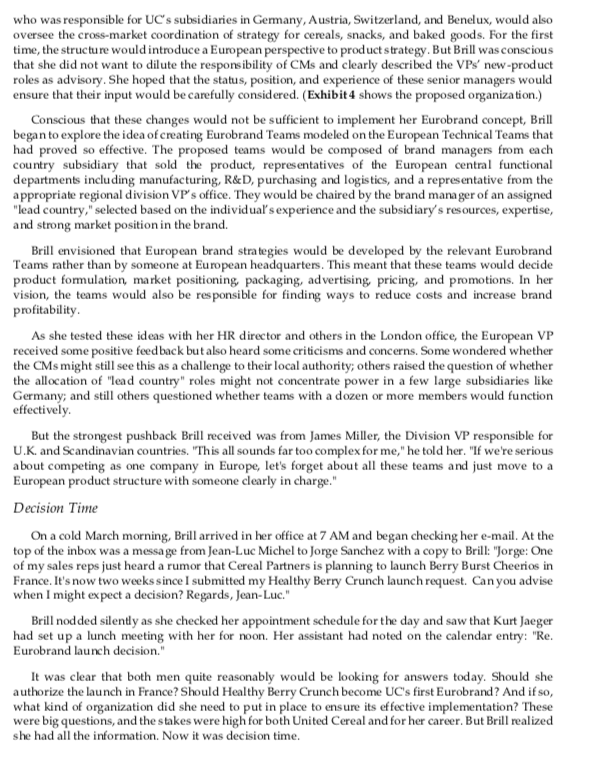

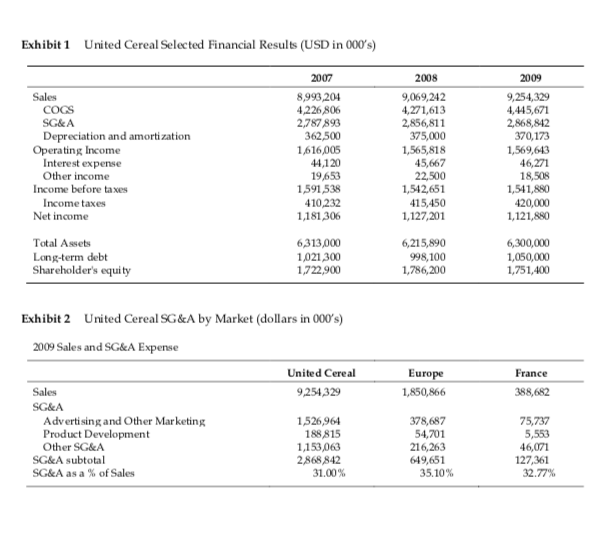

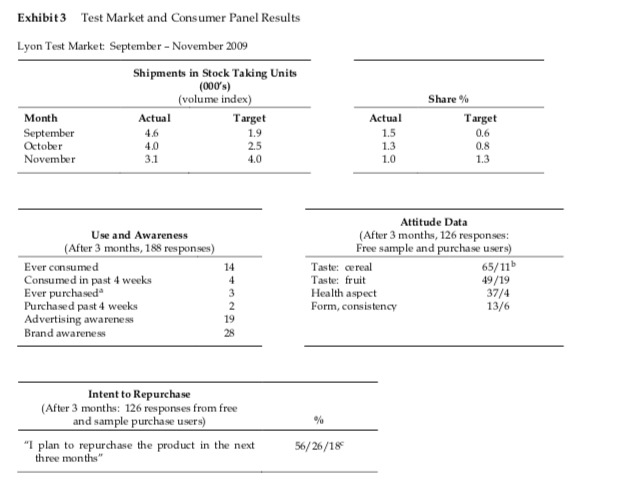

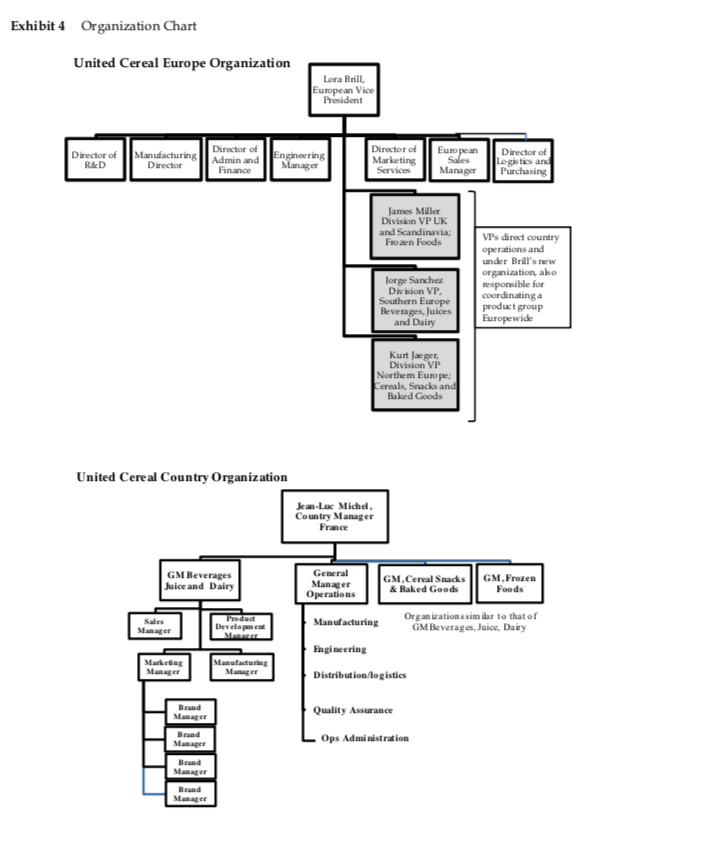

United Cereal: Lora Brill's Eurobrand Challenge Lora Brill, United Cereal's European vice president, was alone in her office early on a cold March morning in 2010. "I've given approval to a dozen big product launches in my career," she thought. "But the implications that this one has for our European strategy and organization make it by far the most difficult I've had to make." The decision related to Healthy Berry Crunch, a new breakfast cereal that the French subsidiary wanted to launch. But Europe's changing market and competitive conditions had led Brill to consider making this the company's first coordinated multimarket Eurobrand launch. It was a possibility that had surfaced some equally challenging organizational questions. "Well it's only 7 AM," Brill thought to herself, smiling. "I have until my lunch appointment to decide!" United Cereal: Breakfast Cereal Pioneer In 2010, United Cereal celebrated its 100th birthday. Established in 1910 by Jed Thomas, an immigrant grocer from England, the company's first product was a packaged mix of cracked wheat, rolled oats, and malt flakes that Thomas sold in his Kalamazoo, Michigan, grocery store. UC, as it was known in the industry, eventually diversified into snack foods, dairy products, drinks and beverages, frozen foods, and baked goods. By 2010 UC was a $9 billion business, but breakfast cereals still accounted for one-third of its revenues and even more of its profits. UC's Corporate Values, Policies, and Practices Thomas grew the company with strong set of values that endured through its history, and "commitment, diligence, and loyalty" were watchwords in UC. As a result, it attracted people who wanted to make a career with the company, and it promoted managers from within. Among its managers United Cereal instilled a strong commitment to "The UC Way," a set of time- tested policies, processes, and practices embedded in iconic company phrases. For example, "Listen tothe customer" was a deeply rooted belief that led UC to become a pioneer in the use of consumer research and focus groups. "Spot the trend, make the market" was another iconic phrase reflecting the high value placed on extensive market testing prior to launching new products. Finally, the value of "Honoring the past while embracing the future" led UC to reject the conventional wisdom that processed food brands had fixed life cycles. Through continuous innovation in marketing and product development, many of its products remained market leaders despite being more than half a century old. United Cereal had a well-earned reputation as an innovator. During its 100-year history, its R&D labs had secured more product and process patents than any other competitor. The company had also pioneered the "brand management" system in the food industry, giving brand managers leadership of cross-functional teams that included manufacturing, marketing, and other functions. Each brand was managed as a profit center and was constantly measured against other brands. Brand managers also competed for R&D and product development resources. Although this system reduced lateral communication, vertical communication was strong, and top managers were very involved in seemingly mundane brand decisions. For example, advertising copy and label changes could require up to a dozen sign-offs before obtaining final approval at the corporate VP level. "It's due to the high value we attach to our brands and our image," explained a senior executive. "But it's also because we give our brand managers responsibility at a very young age." While the company took few risks (a failed launch could cost millions even in small markets), it balanced deliberate cautiousness with a willingness to invest in products it decided to support. "The competitors can see us coming months ahead and miles away," the senior executives said. "But they know that when we get there, we'll bet the farm." The Breakfast Cereal Market Breakfast cereal was in its infancy when UC was founded, but it soon grew to be one of the great food commercialization successes of the 20th century. From the 1890s when Keith Kellogg created corn flakes in his attempt to improve the diet of hospital patients, the industry had grown to achieve world wide revenues exceeding $21 billion in 2009. The U.S. industry included more than 30 companies with combined annual revenues of $12 billion. But just five players accounted for 80% of sales. The industry recognized two categories of cereals- hot and ready-to-eat. The latter accounted for 90% of sales in both the United States and Europe. In this highly competitive industry, more than 10% of revenues was spent on advertising and marketing. Profitability also depended on operating efficiently, managing materials costs, and maximizing retail shelf space. Larger companies had significant advantages in purchasing, distribution, and marketing. In the fight for share, several new-product introductions typically occurred each year. Developing a new brand was time-intensive and expensive, typically taking two to four years. Brand extensions - for example, General Mills's creation of Honey Nut Cheerios- were generally less expensive and less risky due to scale economies that could be leveraged in both production and marketing. But for most U.S. cereal companies, growth was increasingly coming from expansion into new offshore markets, and UC was no exception. UC's European Operations United Cereal entered European markets in 1952 by acquiring an English baked goods company. (Its European offices were still in London.) Over the next 30 years, UC expanded its European presence,typically by acquiring an established company with local market distribution, and then growing it by introducing products from the U.S. line. By 2009, Europe accounted for 20% of United Cereal's world wide sales. European Industry and Competitive Structure Europe's $7 billion breakfast cereal market in 2010 had been overlaid on a variety of national tastes and breakfast traditions-cold meats and cheese in the Netherlands, pastries in Greece, bacon and eggs in Britain, and croissants in France. As a result, per capita consumption of cereals varied significantly across markets from 8 kg. a year in the United Kingdom to 0.5 kg. a year in Italy. Channels also varied widely by country, with supermarkets and hypermarkets accounting for more than 80% of grocery sales in Germany, 37% in France, and only 17% in Italy. U.S.-based companies Kellogg and United Cereal were the largest two competitors in the European market with 26% and 20% share respectively. Cereal Partners, a joint venture between General Mills and Nestle, ranked third with 17%, and U. K-based Weetabix trailed these leaders with 7%. Numerous smaller manufacturers divided the remaining 30% of the market. United Cereal regarded Kellogg as its toughest competitor. Operating through strong national subsidiaries, Kellogg used its volume to lower operating costs and to establish and maintain shelf space. Cereal Partners sold brands that included Cheerios and Shredded Wheat, and leveraged Nestle's technical expertise and its European retailer relationships to compete. Although Weetabix was a smaller private company, like the bigger competitors, it also relied on strong branding and promotions to gain market share. Smaller competitors tended to hold niche market positions, but often challenged larger players with targeted price promotions. UC's Europe Strategy and Organization Major differences across European markets had led United Cereal to establish national subsidiaries, each led by a country manager (CM) who operated with wide latitude to make product and marketing decisions that would maximize the subsidiary's local profit. Based on their market understanding, these CMs usually selected from United Cereal's stable of more than 100 branded products, adapting them to the local situation. Expecting its CMs to conform to its embedded values, policies, and procedures, United Cereal built its subsidiaries as "mini UC's" - exact replicas of the parent organization staffed by managers well- versed in UC's corporate values and practices. So while CMs were able to customize products, adjust manufacturing processes, and adapt advertising and promotions, they had to do so while respecting the "UC Way." This approach unleashed CMs' entrepreneurial instincts and led to strong penetration in most national markets. While many products flourished through such local customization, over time, wide differences in product profiles and market strategies became problematic. For example, in the U.K., the Wake Up! instant coffee brand was formulated as a mild to medium roast beverage promoted as "the perfect milk coffee." But in France and Italy it was sold as a dark roast product and advertised as "the instant espresso." And differences in the positioning of Mother Hubbard's Pies resulted in it being offered as a high-end dessert in Germany, while in the U.K. it was priced aggressively and positioned as "a convenient everyday treat."Increasing Price and Profit Pressure Over the preceding decade, the cereal market in Europe had become increasingly competitive. While total grocery sales had remained remarkably stable through the 2008-09 global recession, all manufacturers had seen their product mix shift toward their lower-priced offerings. Market growth slowed to less than 1% annually, and UC experienced growing price and promotion pressure from Kellogg and Cereal Partners in virtually every country in which it operated. As margins came under pressure, achieving lower costs and implementing more efficient processes became vital. (See Exhibits 1 and 2 for financial performance.) In this changing landscape, some of UC's historical policies came under the microscope. The company's focus on local products and markets, with its need for significant marketing and product development teams in each country, had led to a situation where sales, general and administrative (SG&A) expenses were 25% higher than in the U.S. operations. Furthermore, due to the high costs of developing and launching new products for single country markets, the pace of major new product introductions had slowed considerably in recent years. Lacking the resources for either large-scale market testing or new product launches, most CMs now favored product extensions over new product introductions, and many increasingly relied on cost reductions in their existing portfolios to maintain profits. It was a situation that raised concerns. United Cereal Response The earliest response to these problems had been initiated by Ame Olsen, a Norwegian appointed as UC's European VP in 2002 with a mandate to invigorate the product portfolio and reverse declining profitability. Olsen quickly reorganized R&D, reinforcing the European research facility near UC Europe's headquarters in London. To link these food scientists working on basic issues with the subsidiary-based technologists refining and testing products in local markets, Olsen created a European Technical Team (ETT) for each major product group. Each ETT was composed of the strongest local product development technologists teamed with central R&D scientists to provide overall direction on European product development. To facilitate collaboration, Olsen encouraged transfers between the London team and the country offices, and also strengthened relationships with the R&D labs in Kalamazoo. In 2004, Olsen expanded this technical program into what he called the "Europeanization Initiative," aimed squarely at product market strategies. His first test was UC's frozen fruit juice line, which had languished for years. He was convinced that there was little difference in tastes for fruit juice across markets, and that there were significant benefits in standardizing the products as well as their marketing, promotion, and advertising. He transferred a senior manager from Germany to the European headquarters and gave him responsibility to standardize products, develop a coordinated Europewide strategy, and oversee implementation across subsidiaries. The experiment was a disaster. Local CMs perceived the initiative as a direct challenge to their local autonomy-a belief made worse by the domineering personality of the individual they called the "European Juice Nazi." While they reluctantly implemented his imposed product positioning and advertising directives, they provided minimal support from the local sales forces that remained under their control. Unsurprisingly, the frozen juice category stagnated, and eventually responsibility for juice products was returned to the countries. In 2006, Olsen was transferred to Kalamazoo in a senior marketing role, and Lora Brill, former UK country manager, became the new European vice president. In the aftermath of the 2008/2009 recession, with continuing pressure on margins, Brill needed to leverage marketing resources- thelargest controllable expense in subsidiary budgets. Eventually, she too became convinced that the coordinated European approach that had succeeded in product development could be adapted for product marketing. It was in this context that she began to pursue an idea she referred to as the "Eurobrand" concept. And in 2010, a proposal by the French subsidiary to launch Healthy Berry Crunch offered the possibility of a first test case. The Healthy Berry Crunch Project In the late 1990s, aging baby boomers took an increased interest in natural, healthy foods in both the United States and Europe. This created a challenge for cereal companies whose highly processed products were typically high in sugar. In response, some felt that the addition of fruit could provide "a halo of health." The main technical problem was that fruit's moisture content made it difficult to maintain the crispness and shelf life of cereal. But a solution was found in the use of freeze-dried fruits, which also retained their color and shape in a cereal mix. The French Opportunity In 2003, Kellogg introduced Special K with freeze-dried strawberries in the U.K., and in 2007 Cereal Partners launched Berry Burst Cheerios. Seeing interest in healthy breakfast foods growing in France, UC's French country manager Jean-Luc Michel felt there could be a market for an organic fruit-based cereal in his market. Although Kellogg's Special K with Strawberries had been launched in France in 2006, to date it was alone in this new segment. In 2008, Michel started initial product development and testing in France, later involving the ETT to develop detailed specifications. He recommended an organic blueberry-based cereal as a product extension of Healthy Crunch-a UC cereal already positioned in the health-conscious adult segment but experiencing no growth in recent years. He felt the use of blueberries, with their well-known antioxidant qualities, would reinforce the positioning. In keeping with UC policy, as soon as the product was ready, Michel implemented a full-scale test market in Lyon. (See Exhibit 3 for test market results.) Results were mixed, with some consumers finding the berries too tart. With the "intention to repurchase" rate below UC's 60% minimum target, an alternate raspberry-based product was developed but proved too expensive to manufacture. So a sweeter blueberry version was taste-tested with focus groups in six French cities. While lacking the validated full test-market data UC policy required, Michel felt focus group data indicating a 64% intention to repurchase was very promising. He was ready to launch: It's clearly a big improvement on our initial test market data. But this is a new product concept, so any test only provides a general indication. In a fast-growing category like this, we need to launch now before competitors preempt us.... We've been in development and testing for more than a year. We can't wait three months more to mount another full-scale test market. Besides, my budget won't support the $2 million it would cost. The European Debate Even before Michel set about obtaining launch approval, Brill was aware of his intention and had begun exploring the idea of launching Healthy Berry Crunch Europewide to test her nascent Eurobrand concept. Her director of finance had estimated that implementing coordinated European product market strategies could result in staff reductions and other savings that would cut productdevelopment and marketing costs by 10% to 15% over three years. Since these costs were running above 23% of sales in Europe, the savings could be very significant. Brill next met with Kurt Jaeger, her Division VP responsible for Northern Europe and the person she regarded as Europe's most knowledgeable about breakfast cereal strategy. He was strongly in favor of a coordinated European rollout: Our strategy of responding to local market differences was right for its time, but not necessarily today. Consumer tastes are converging, old cultural habits are disappearing, and EU regulation of labeling, advertising, and general marketing practices is eroding market differences..I've had my CMs in Germany and Benelux conduct consumer panels on Healthy Berry Crunch. The samples are small, but it's encouraging that their results are similar to the French panel findings..Our biggest risk is the competition. The PodCafe debacle shows that they are way ahead of us in coordinating European strategy. The "PodCafe debacle" to which Jaeger referred had occurred following UC's introduction of its innovative Pod Cafe single-serve coffee pods for home espresso machines in Germany in 2003. But by the time the French subsidiary decided to launch its version in 2006, and Italy the following year, the coffee pod market had become crowded with copycat products, and United Cereal's product was relegated to a third-place share in both of those key markets. But Jorge Sanchez, the Division VP for Southern Europe to whom Jean-Luc Michel reported, was less enthusiastic about the Eurobrand idea. He told Brill: Although Jean-Luc has only been in his CM role for 18 months, I think his enthusiasm for Healthy Berry Crunch is just the kind of entrepreneurial initiative we want from our CM's. But a launch like this will cost at least $20 million in France -10 times my approval level, and twice yours. Frankly, I have real concerns about whether his budget can support it.... Even if France goes ahead, my Italian CM tells me he doesn't think he could get shelf space for a specialty cereal. And our struggling Spanish subsidiary is still in recovery from the recession. There's no way they have a budget for a new launch now. Brill also heard from her old boss, Ame Olsen, who told her that word of the proposed French launch had already reached to Kalamazoo. Olsen thought she should know about a conversation he recently had with the company's executive vice president: Lou's an old traditionalist who has spent his whole career here in corporate headquarters, and sees himself as a guardian of the company's values. He told me over lunch that he's worried that Europe is rushing into this launch, shortcutting the product, consumer, and market research that has ensured UC's past successes. His is one of the signatures you'll need to authorize the launch, so I thought you should know his views. The Organizational Challenge As she listened to this different advice, Brill was also aware that her decision would be based on organizational as well as strategic considerations. Having witnessed the disastrous European fruit juice strategy years earlier, she was determined to learn from its failure. In meetings with her HR director, she began to develop some alternative organizational proposals. For some time, she had been planning to expand the responsibilities of her three regional vice presidents. In addition to their current roles supervising subsidiaries by region, she proposed giving each of them Europewide coordinating responsibility for several products. For example, Kurt Jaeger,who was responsible for UC's subsidiaries in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Benelux, would also oversee the cross-market coordination of strategy for cereals, snacks, and baked goods. For the first time, the structure would introduce a European perspective to product strategy. But Brill was conscious that she did not want to dilute the responsibility of CMs and clearly described the VPs' new-product roles as advisory. She hoped that the status, position, and experience of these senior managers would ensure that their input would be carefully considered. ( Exhibit 4 shows the proposed organization.) Conscious that these changes would not be sufficient to implement her Eurobrand concept, Brill began to explore the idea of creating Eurobrand Teams modeled on the European Technical Teams that had proved so effective. The proposed teams would be composed of brand managers from each country subsidiary that sold the product, representatives of the European central functional departments including manufacturing, R&D, purchasing and logistics, and a representative from the appropriate regional division VP's office. They would be chaired by the brand manager of an assigned "lead country," selected based on the individual's experience and the subsidiary's resources, expertise, and strong market position in the brand. Brill envisioned that European brand strategies would be developed by the relevant Eurobrand Teams rather than by someone at European headquarters. This meant that these teams would decide product formulation, market positioning packaging, advertising pricing, and promotions. In her vision, the teams would also be responsible for finding ways to reduce costs and increase brand profitability. As she tested these ideas with her HR director and others in the London office, the European VP received some positive feedback but also heard some criticisms and concerns. Some wondered whether the CMs might still see this as a challenge to their local authority; others raised the question of whether the allocation of "lead country" roles might not concentrate power in a few large subsidiaries like Germany; and still others questioned whether teams with a dozen or more members would function effectively. But the strongest pushback Brill received was from James Miller, the Division VP responsible for U.K. and Scandinavian countries. "This all sounds far too complex for me," he told her. "If we're serious about competing as one company in Europe, let's forget about all these teams and just move to a European product structure with someone clearly in charge." Decision Time On a cold March morning, Brill arrived in her office at 7 AM and began checking her e-mail. At the top of the inbox was a message from Jean-Luc Michel to Jorge Sanchez with a copy to Brill: "Jorge: One of my sales reps just heard a rumor that Cereal Partners is planning to launch Berry Burst Cheerios in France. It's now two weeks since I submitted my Healthy Berry Crunch launch request. Can you advise when I might expect a decision? Regards, Jean-Luc." Brill nodded silently as she checked her appointment schedule for the day and saw that Kurt Jaeger had set up a lunch meeting with her for noon. Her assistant had noted on the calendar entry: "Re. Eurobrand launch decision." It was clear that both men quite reasonably would be looking for answers today. Should she authorize the launch in France? Should Healthy Berry Crunch become UC's first Eurobrand? And if so, what kind of organization did she need to put in place to ensure its effective implementation? These were big questions, and the stakes were high for both United Cereal and for her career. But Brill realized she had all the information. Now it was decision time.Exhibit 1 United Cereal Selected Financial Results (USD in 000's) 20 07 2005 20 09 Sales 8,993,204 9,069,242 9,254,329 COGS 4,226,806 4,271,613 4,445,671 SG&A 2,787 893 2,856,811 2,868,842 Depreciation and amortization 362,500 375,000 370,173 Operating Income 1,616,005 1,565,818 1,569,643 Interest expense 44,120 45,667 46,271 Other income 19,653 22,500 18,508 Income before taxes 1,591,538 1,542,651 1,541,850 Income taxes 410,232 415,450 420,000 Net income 1,181,306 1,127,201 1,121,850 Total Assets 6,313,000 6,215,890 6,300,000 Long-term debt 1,021,300 998,100 1,050,000 Shareholder's equity 1,722,900 1,786,200 1,751,400 Exhibit 2 United Cereal SG&A by Market (dollars in 000's) 2009 Sales and SG&A Expense United Cereal Europe France Sales 9,254,329 1,850,866 388,652 SG&A Advertising and Other Marketing 1,526,964 378,687 75,737 Product Development 188,815 54,701 5.553 Other SG&A 1,153,063 216,263 46,071 SG&A subtotal 2,868,842 649,651 127,361 SG&A as a % of Sales 31.00% 35.10% 32.77%Exhibit3 Test Market and Consumer Panel Results Lyon Test Market: September - November 2009 Shipments in Stock Taking Units (000's) (volume index) Share % Month Actual Target Actual Target September 4.6 1.9 1.5 0.6 October 4.0 2.5 1.3 0.8 November 3.1 4.0 1,0 1.3 Attitude Data Use and Awareness (After 3 months, 126 responses: (After 3 months, 185 responses) Free sample and purchase users) Ever consumed 14 Taste: cereal 65/11b Consumed in past 4 weeks Taste: fruit 49/19 Ever purchased* Health aspect 37/4 Purchased past 4 weeks Form, consistency 13/6 Advertising awareness 19 Brand awareness 28 Intent to Repurchase (After 3 months: 126 responses from free and sample purchase users) "I plan to repurchase the product in the next 56/26/185 three months"Exhibit 4 Organization Chart United Cereal Europe Organization Lora Brill, European Vice President Director of Engineering Director of Manufacturing Director of European Director of R&D Admin and Manager Marketing Director Sales Logetes and Finance Services Manager Purchasing James Miller Division VP UK and Scandinavia; Frozen Foods VP's direct country operations and under Brill's new organization, abo forge Sanchez responsible for Division VP, Southern Europe coordinating a Beverages, Juices product group and Dairy Europewide Kurt Jaeger, Division VP Northem Europe: Cereals, Snacks and Baked Goods United Cereal Country Organization Jean-Luc Michel Country Manager France GM Beverages General GM, Cereal Snacks GM, Frozen Juice and Dairy Manager & Baked Goods Foods Operations Organizationssim ibar to that of Developucn Manufacturing Manager GM Beverages, Juice, Dairy Engineering Marketing Amulecturing Manager Manager Distribution/logistics Brand Quality Assurance Manager Brand Ops Administration Manager Brand Brand