Question

Fannie, Freddie, Wall Street, Main Street, and the Subprime Mortgage Market: Of Moral Hazards Background on Fannie Mae Fannie Mae was created as a different

Fannie, Freddie, Wall Street, Main Street, and the Subprime

Mortgage Market: Of Moral Hazards

Background on Fannie Mae

Fannie Mae was created as a different sort of business entity, a shareholder-owned corporation with a federal charter. The federal government created Fannie Mae in 1938 during the Roosevelt administration to increase affordable housing availability and to attract investment into the housing market. The charge to Fannie Mae was to be sure that there was a stable mortgage market with consistent availability of mortgage funds for consumers to purchase homes. Initially, Fannie Mae was federally funded, but in 1968, it was rechartered as a shareholder-owned corporation with the responsibility of obtaining all of its capital from the private market, not the federal government. On its website, Fannie Mae describes its commitment and mission as follows:

Expand access to homeownership for first-time home buyers and help raise the minority homeownership rate with the ultimate goal of closing the homeownership gap entirely;

Make homeownership and rental housing a success for families at risk of losing their homes;

Expand the supply of affordable housing where it is needed most, which includes initiatives for workforce housing and supportive housing for the chronically homeless; and

Transform targeted communities, including urban, rural, and Native American, by channeling all the companys tools and resources and aligning efforts with partners in these areas.

A Model Corporate Citizen

In 2004, Business Ethics magazine named Fannie Mae the most ethical company in the United States. It had been in the top ten corporate citizens for several years (number 9 in 2000 and number 3 in 2001 and 2002).54 Marjorie Kelly, the editor-in-chief of the magazine (see Reading 3.6), described the standards for the award, which was created in 1996, as follows:

Just what does it mean to be a good corporate citizen today? To our minds, it means simply this: treating a mix of stakeholders well. And by stakeholders, we mean those who have a stake in the firmbecause they have risked financial, social, human, and knowledge capital in the corporation, or because they are impacted by its activities. While lists of stakeholders can be long, we focus on four groups: employees, customers, stockholders, and the community. Being a good citizen means attending to the companys impact on all these groups.55

In 2001, the magazine explained why Fannie Mae was one of the countrys top corporate citizens:

ranked near the top of everyones best list, including Fortunes Best Companies for Minorities, Working Mothers Best Companies for Working Mothers, and The American Benefactors Americas Most Generous Companies. Franklin D. Raines, an African American, is CEO, and there are two women and two minorities among the companies eight senior line executives.56

In 2002, Business Ethics described third-ranked Fannie Mae as follows: The purpose of Fannie Mae, a private company with an unusual federal charter, is to spread home ownership among Americans. Its ten-year, $2 trillion programthe American Dream Commitmentaims to increase home ownership rates for minorities, new immigrants, young families, and those in low-income communities.

In 2001, over 51 percent of Fannie Maes financing went to low- and moderateincome households. A great deal of our work serves populations that are underserved, typically, and weve shown that its an imminently bankable proposition, said Barry Zigas, senior vice president in Fannie Maes National Community Lending Center. It is our goal to keep expanding our reach to impaired borrowers and to help lower their costs.

That represents a striking contrast to other financial firms, many of which prey upon rather than help low-income borrowers. To aid the victims of predatory lenders, Fannie Mae allows additional flexibility in underwriting new loans for people trapped in abusive loans, if they could have initially qualified for conventional financing. In January

the company committed $31 million to purchasing these type of loans. 5

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) is a federal statute that established a government program to get people who would otherwise not qualify (i.e., no credit history and no down payment) into homes with the goals of helping these folks and thereby revitalizing blighted areas. Banks and lenders were evaluated for their commitment to these loans, and no bank or lender wanted a bad rating.

Simultaneously, the federal government anticipated push-back from lenders who would point out that these were high-risk loans and required greater returns. However, lenders were evaluated for their CRA commitment, which included their creativity in granting the loans. In addition, lenders faced prosecution by the Justice Department for discrimination in lending if their loan portfolios did not include a sufficient number of CRA loans. All the while, Fannie Mae served as the purchaser for these loans, eventually packaging them and selling them as securitized mortgage pools. The CRA loans had borrowers with less equity, higher default rates, and more foreclosures. There was also an exacerbating effect of this false sense of security on the part of the high-risk borrowers about their mortgages. Because these risky borrowers were not really anteing up the actual cost of their homes (and remember, these were folks who had never had a mortgage before, had bad credit histories, and may not have had much in the way of financial literacy), they overextended and overspent in other areas. In short, they were maxed out in all areas because they were lulled into a false sense of financial security with such a low mortgage payment. Because Fannie Mae owned or guaranteed half of the $12 trillion mortgage debt in the United States, any problems with those mortgages could and did lead to a financial crisis for Fannie, the U.S. stock market, and the economy. 58 Then Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan warned of the looming problems at Fannie Mae in 2005. He testified before Congress, The Federal Reserve Board has been unable to find any credible purpose for the huge balance sheets built by Fannie and Freddie other than profit.59 Others, including the St. Louis Federal Reserve chairman, William Poole, warned that the huge debt load rendered Fannie and Freddie insolvent.

The Darker Side of Corporate Citizen Fannie

Even as the mortgage issues were evolving under the radar and Fannie was being recognized

for its corporate citizenship, there were issues in Fannies operations that went undetected

for nearly a decade.

Fannie Mae: The Super-Achiever with an EPS Goal

Fannie Mae was a company driven to earnings targets through a compensation system tied to those results. And Fannie Mae had a phenomenal run based on those incentives in terms of its financial performance:

For more than a decade, Fannie Mae achieved consistent, double-digit growth in earnings.60

In that same decade, Fannie Maes mortgage portfolio grew by five times to $895 billion.61

From 2001 to 2004, its profits totaled $24 billion.62

Through 2004, Fannie Maes shares were trading at over $80.63

Fannie Mae was able to smooth earnings through decisions on the recording of interest costs, and used questionable discretion in determining the accounting treatment for buying and selling its mortgage assets. Those decisions allowed executives at the company to smooth earnings growth with a resulting guaranteed payout to them under the incentive plans.64

Those incentive plans were based on earnings per share targets (EPS) that had to be reached in order for the officers to earn their annual bonuses. The incentive plans began in 1995, with a kick-up in 1998 as Franklin Raines, then chairman and CEO, set a goal of doubling the companys earnings per share (EPS) from $3.23 to $6.46 in five years.65 Raines, the former budget director for the Clinton administration, was able to make the EPS goal a part of Fannie Maes culture. Mr. Raines said, The future is so bright that I

am willing to set a goal that our EPS will double over the next five years.66 Sampath Rajappa, Fannie Maes senior vice president of operations risk (akin to the Office of Auditing), gave the following pep talk to his team in 2000, as the EPS goals continued:

By now every one of you must have a 6.46 branded in your brains. You must be able to say it in your sleep, you must be able to recite it forwards and backwards, you must have a raging fire in your belly that burns away all doubts, you must live, breathe and dream 6.46, you must be obsessed on 6.46. . . . After all, thanks to Frank, we all have a lot of money riding on it. . . . We must do this with a fiery determination, not on some days, not on most days but day in and day out, give it your best, not 50%, not 75%, not 100%, but 150%. Remember Frank has given us an opportunity to earn not just our salaries, benefits, raises . . . but substantially over and above if we make 6.46.

So it is our moral obligation to give well above our 100% and if we do this, we would have made tangible contributions toward Franks goals.67

For 1998, the size of the annual bonus payout pool was linked to specific EPS targets:

Earnings Per Share (EPS) Range for 1998 AIP Corporate Goals

$3.13 minimum payout $3.18 target payout $3.23 maximum payout68

For Fannie Mae to pay out the maximum amount in incentives in 1998, EPS would have to come in at $3.23. If EPS was below the $3.13 minimum, there would be no incentive payout. The 1998 EPS was $3.2309. The maximum payout goal was met, as the OFHEO report noted, right down to the penny. The final OFHEO report concluded that the executive team at Fannie Mae determined what number it needed to get to the maximum EPS level and then worked backwards to achieve that result. One series of e-mails finds the executives agreeing on what number they were comfortable with as using for the volatility adjustment.69

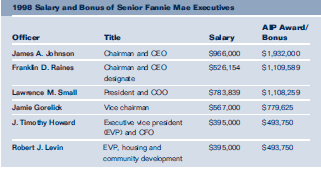

The following table shows the difference between salary (what would have been paid if the minimum target were not met) and the award under the Incentive Plan (AIP).

Right down to the penny was not a serendipitous achievement. For example, Fannie Maes gains and losses on risky derivatives were kept off the books by treating them as hedges, a decision that was made without determining whether such treatment qualified under the accounting rules for exemptions from earnings statements. These losses were eventually brought back into earnings with a multibillion impact when these types of improprieties were uncovered in 2005.70

Fannie Mae and Volatility

Fannie Maes policies on amortization, a critical accounting area for a company buying and holding mortgage loans, were developed by the chief financial officer (CFO) with no input from the companys controller. Fannie Maes amortization policies were not in compliance with GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles).71 The amortization policies relied on a computer model that would shorten the amortization of the life of a loan in order to peak earnings performance with higher yields. Fascinatingly, the amortization policies were developed because of a mantra within the company of no more surprises.72 The philosophy was that in order to attract funding for the mortgage market, there needed to be stability that would attract investors. The officers at the company reasoned that volatility was a barrier to accomplishing its goals of a stable and available source of mortgage funds for homes. When the computer model was developed, the officers reasoned that they were simply adjusting for what was arbitrary volatility. However, arbitrary volatility turned out to be a difficult-to-grasp concept for those outside Fannie Mae.73 Further, the volatility measures and adjustments appeared to have a direct correlation with the EPS goals that resulted in the awards to the officers. Even those within Fannie Mae struggled to explain to investigators what was really happening with their adjustments.

In the OFHEO report, an investigator asked Janet Pennewell, Fannie Maes vice president of resource and planning, What is arbitrary volatility in earnings? Ms. Pennewell responded,

Arbitrary volatility, in our view, was introduced whenI can give you an example of what would cause, in our view, arbitrary volatility. If your constant effective yield was dramatically different between one quarter and the next quarter because of an arbitrary decision you had or viewchanging your view of long-term interest rates that caused a dramatic change in the constant effective yield that you were reporting, you could therefore be in a position where you might be booking 300 million of income in one quarter and 200 million of expense in the next quarter, introduced merely by what your assumption about future interest rates was. And to us that was arbitrary volatility because it really just literally because of your view, your expectation of interest rate and the way that you were modeling your premium and discount constant effective yield, you would introduce something into your financial statements that, again, wasnt very reflective of how you really expect that mortgage to perform over its entire expected life, and was not very representative of the fundamental financial performance of the company.74

The operative words to us appeared to have fueled accounting decisions. But, there was an overriding problem with Fannie Maes reliance on arbitrary volatility. Fannie Mae had fixed-rate mortgages in its portfolio. Market fluctuations on interest rates were irrelevant for most of its portfolio.75

Fannie Maes Accounting

and others met with the SEC to discuss the agencys demand for a restatement in 2005, the SEC told Raines that Fannies financial reports were inaccurate in material respects. When pressed for specifics, Donald Nicolaisen, head of the SECs accounting division, held up a piece of paper that represented the four corners of what was permissible under GAAP and told Raines, You werent even on the page.76 The OFHEO report on Fannie Maes accounting practices paints an ugly picture of a company tottering under the weight of baleful misdeeds that have marked the corporate scandals of the past three years: dishonest accounting, lax internal controls, insufficient capital, and me-first managers who only care that earnings are high enough to get fat bonuses and stock options.77

When Franklin Raines and Fannie Mae CFO J. Timothy Howard were removed by the board at the end of 2005, Daniel H. Mudd, the former chief operating officer during the time frame in which the accounting issues arose, was appointed CEO.78 When congressional hearings were held following the OFHEO report, Mudd testified that he was as shocked as anyone about the accounting scandals at the company at which he had served as a senior officer.79 He added, I was shocked and stunned, when Senator Chuck Hagel confronted Mudd with Im astounded that you would stay with this institution.80

There were other issues that exacerbated the accounting decisions at Fannie Mae. Mr. Howard, as CFO, had two functions: to set the targets for Fannies financial performance and make the calls on the financial reports that determined whether those targets (and hence his incentive pay and bonuses) would be met.81 In effect, the function of targets and determination of how to meet those targets rested with one officer in the company. The internal control structure at Fannie Mae was weak even by the most lax internal control standards.82

In 1998, when Fannie Mae CEO Raines set the EPS goals, the charge spread throughout the company, and the OFHEO report concluded that the result was a culture that improperly stressed stable earnings growth.83 Also in 1998, Armando Falcone of the OFHEO issued a warning report that challenged Fannie Maes accounting and stunning lack of internal controls. The report was buried until the 2004 report, readily dismissed by Fannie Mae executives and members of Congress who were enamored of Fannies financial performance, as the work of pencil brains who did not understand a model that was working.84

The Unraveling of the Fannie Mae Mystique

Employees within Fannie Mae did begin to raise questions. In November 2003, a full year before Fannie Maes issues would become public, Roger Barnes, then an employee in the Controllers Office at the company, left Fannie Mae because of his frustration with the lack of response from the Office of Auditing at Fannie. He had provided a detailed concern about the companys accounting policy that internal audit did not investigate in an appropriate manner.85 No one at Fannie Mae took any steps to investigate Barness warnings about the flaws in the computer models for amortization. Worse, in one instance, Mr. Barnes notified the head of the Office of Auditing that at least one on-top adjustment had been made in order to make Fannies results meet those that had been forecasted.86 At the time Barnes raised his concern, Fannie Mae had an Ethics and Compliance Office, but it was housed within the companys litigation division and was headed by a lawyer whose primary responsibility was defending the company against allegations and suits by employees.

When those in charge of the Office of Auditing (Mr. Rajappa, of EPS 6.46 pep talk fame, was the person who handled the allegations and investigation) investigated Barness allegations, they were not given access to the necessary information and the investigation was dropped.87 Many of the officers at Fannie disclosed in interviews that they were aware of the Barnes allegation of an intentional act related to financial reporting, but none of them followed up on the issue or required an investigation.88 Barnes was

correct, but was ignored, and he left Fannie Mae. He would later be vindicated by the OFHEO report, but the report was not issued until after he had left Fannie Mae.89 Fannie Mae settled with Barnes before any suit for wrongful termination was filed. In 2002, at about the same time Barnes was raising his concerns internally, the Wall Street Journal began raising questions about Fannie Maes accounting practices.90 Those concerns were reported and editorialized in that newspaper for two years. No action was

taken, however, until the OFEHO interim report was released.

The final OFHEO report noted that Fannie Maes then CEO, Daniel Mudd, listened in 2003 as employees expressed concerns about the companys accounting policies. However, Mr. Mudd took no steps to follow up on either the questions or concerns that the employees had raised in the meeting that also subsequently turned out to accurately reflect the financial reporting missteps and misdeeds at Fannie Mae.91 The special report done for Fannie Maes board indicates that the Legal Department at Fannie Mae was aware of the Barnes allegations, but it deferred to internal audit for making any decisions

about the merits of the allegations.92

ThenNew York Attorney General Eliot Spitzers (Mr. Spitzer became governor in 2007 and resigned in 2008 because of a sex scandal) investigation into insurance companies added an aside to the Fannie Mae scandal and revealed yet another red flag from a Fannie Mae employee. In 2002, Fannie Mae bought a finite-risk policy from Radian Insurance to shift $40 million in income from 2003 to 2004. Radian booked the transaction as a loan, but Fannie called it an insurance policy on its books. In a January 9, 2002, email, Louis Hoyes, Fannie Maes chief for residential mortgages, wrote about the Radian deal, I would like to express an extremely strong no vote. . . . Should we be exposing Fannie Mae to this type of political risk to move $40 million of income? I believe not.93 No further action was taken on the question raised; the deal went through as planned, and the income was shifted to another year.

The Fallout at Fannie Mae

part of that settlement, Fannie Maes board agreed to new officers, new systems of internal control, and the presence of outside consultants to monitor the companys progress. The agency concluded that it would take years for Fannie Mae to work through all of the accounting issues and corrective actions needed to prevent similar accounting missteps in the future.95 Fannie Mae settled charges of accounting issues with the SEC for $400 million. 96 Investigations into the role of third parties and their relationships to Fannie Mae and actions and inactions with them are pending.97 Former head of the SEC Harvey Pitt commented, When a company has engaged in wrongful conduct, the inquiry [inevitably turns to] who knew about it, who could have prevented it, who facilitated it.98

The head of the OFHEO, upon release of the Fannie Mae report, said of the companys operations, More than any other case Ive seen, its all there.99

When he was serving as the CEO of Fannie Mae as well as the chair of the Business Roundtable, Franklin Raines testified before Congress in March 2002 in favor of passage of SarbanesOxley. The following are excerpts from his testimony, which began with a reference to the tone at the top:

The success of the American free enterprise system obtains from the merger of corporate responsibility with individual responsibility, and The Business Roundtable believes that responsibility starts at the top.

We understand why the American people are stunned and outraged by the failure of corporate leadership and governance at Enron. It is wholly irresponsible and unacceptable for corporate leaders to say they did not knowor suggest it was not their duty to knowabout the operations and activities of their company, particularly when it comes to risks that threaten the fundamental viability of their company.

First, the paramount duty of the board of directors of a public corporation is to select and oversee competent and ethical management to run the company on a day-to-day basis.

Second, it is the responsibility of management to operate the company in a competent and ethical manner. Senior management is expected to know how the company earns its income and what risks the company is undertaking in the course of carrying out its business. Management should never put personal interests ahead of or in conflict with the interests of the company.10

The final Fannie Mae report was issued in May 2006 with no new surprises or altered conclusions beyond what appeared in the interim report.101

Fannie Mae concluded the financial statement questions and issues with, among other things, a $6.3 billion restatement of revenue for the period from 1998 through 2004. Mr. Raines earned $90 million in bonuses for this period. The report also concluded that management had created an unethical and arrogant culture with bonus targets that were achieved through the use of cookie jar reserves that manipulated earnings.102 OFHEO filed 101 civil charges against Mr. Raines, former Fannie Mae CFO J.

Timothy Howard, and former Controller Leanne G. Spencer. The suits asked for the return of $115 million in incentive plan payouts to the three.103 The suit also asked for $100 million in penalties. The three settled the case by agreeing to pay $31.4 million. Mr. Raines issued the following statement when the case was settled, While I long ago accepted managerial accountability for any errors committed by subordinates while I was CEO, it is a very different matter to suggest that I was legally culpable in any way, Raines said in a statement. I was not. This settlement is not an acknowledgment of wrongdoing on my part, because I did not break any laws or rules while leading Fannie Mae. At most, this is an agreement to disagree.104

The Evolving Financial Meltdown and the Conflicts

Once the restatement was completed, Fannie Mae returned to increasing its mortgage portfolio. But, Fannie also built relationships. Through its foundation, the Fannie Mae Foundation, Fannie (subsequently investigated by the IRS for violating the use of a charitable foundation for political purposes) made donations to charities on the basis of the political contacts they were able to list on their applications for funding.105 Bruce Marks, the CEO of Neighborhood Assistance Corporation, a recipient of Fannie Foundation funds explained, Many institutions rely on Fannie Mae and understand that those funds are contingent on public support for its policies. Fannie Mae has intimidated virtually all of them into remaining silent.106 Donations went to those groups that supported CRA loans, including the annual fundraisers for several congressional groups. In exchange, when regulatory or legislative action was pending that was unfavorable to Fannie, those members of Congress would come out in support of Fannie, what one member of Congress called, a gorilla that has outgrown its cage.107 When the SEC wanted to push to have Fannie Mae register its securities as other companies did, at least six members of Congress wrote letters of support for Fannie and the SEC backed down from its demand.

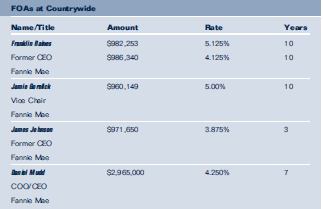

Fannies board members also stood to benefit from continuing Fannies growth and mortgage policies. Lenders, seeking to curry favor with Fannie in having it purchase their mortgages, offered special loan terms to Fannie executives and board members, as well as to members of Congress. The following chart lists those loans that were given by Countrywide under a special program that was nicknamed, FOA, for

Friends of Angelo.108 Angelo Mozilo was the CEO of Countrywide, a company that collapsed under the weight of its subprime mortgages, nearly all of which were purchased by Fannie Mae.

Between 2005 and 2008, Fannie Mae guaranteed $270 billion in risky loans, an amount that was three times the amount of risky loans it had guaranteed in all of its existence (since 1938, when it was created during the Roosevelt administration). The mortgage loans were risky because the income of the borrowers had not been verified, the borrowers had little or no equity in the property, the real level of payments that would be due under the loans did not take effect until three to five years after, and most of the borrowers had little or a poor credit history.

When employees expressed concerns that there were too many mortgages being evaluated, that the computer system was not effective in determining risk, and that Fannies exposure was too great, Mr. Mudd, then-CEO, instructed them, Get aggressive on risktaking or get out of the company.109 During the years from 2004 to 2006, the company operated without a permanent chief risk officer. When a permanent risk officer was hired in 2006, he advised Mr. Mudd to scale back on risk. Mr. Mudd rebuffed the suggestion because he explained that Congress and shareholders wanted him to take more risks. In September 2008, the federal government had to pay $200 billion in order to restore Fannie to solvency and prevent the quake that would have shaken other firms if Fannie had defaulted on its guarantees.

3. What observations can you make about incentive plans and earnings management? Incentive plans and internal controls?

4. Why was dealing with the volatility not the issue? Why were the changes in the numbers necessary?

1998 Salary and Bonus of Senior Fannie Mae Executives AP Award Salary James A. Johnson Chaiman and CEO Franklin D. Raines Chaiman and CEO $1932,000 $526,154 $1,109,589 designate ST83839 $1.108.259 Lawrence M. Small President and COO Jamie Gorelidk $56 T000 J. Tramoty Howard Eecutve vice president $493 T50 (EVP) and CFO Robert J. Levin EVP, housing and $493 T50 community developmentStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started