Question: From the above answer the below questions ( Case 8 Eastman Kodak's Quest for a Digital Future ) What was the nature and sources of

From the above answer the below questions (Case 8 Eastman Kodak's Quest for a Digital Future)

- What was the nature and sources of organizational inertia in this case?

- Explain disruptive technology and architectural innovation as it relates to this case.

- What general lessons for the management of strategic change did you gain from this case and how do they apply to the current state of this industry?

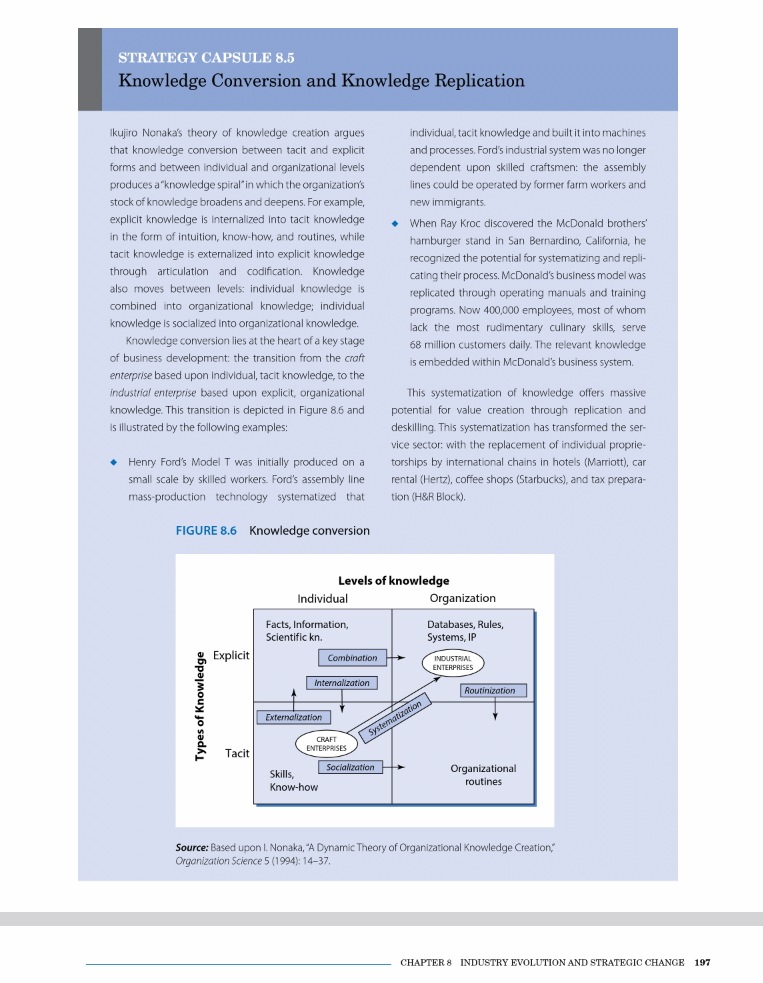

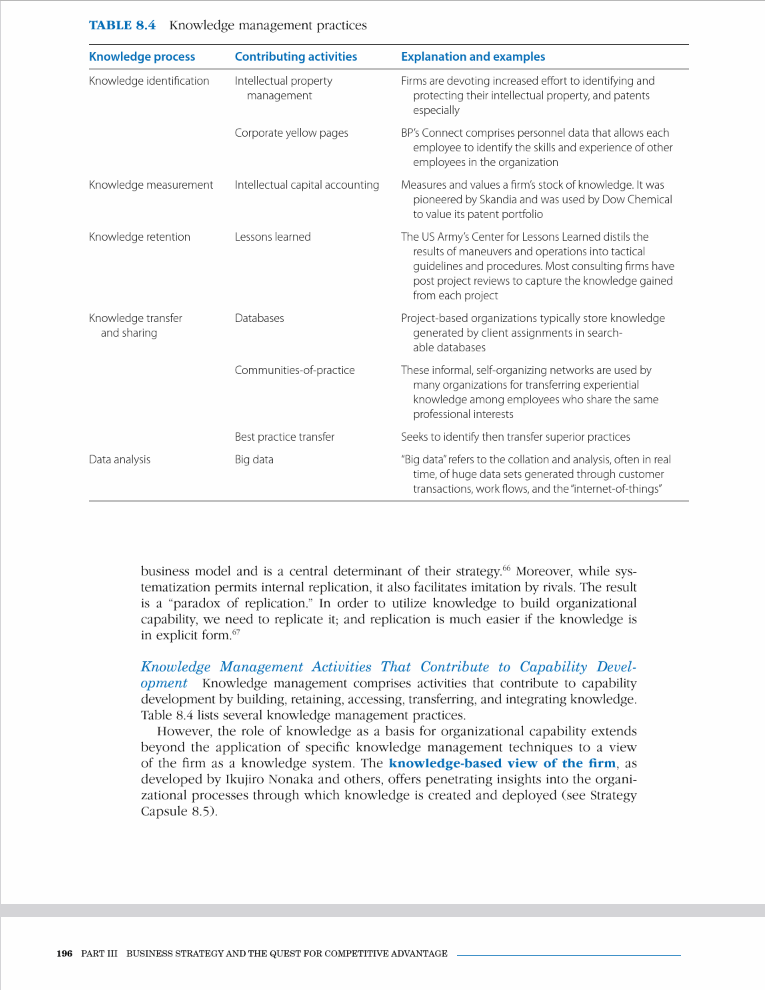

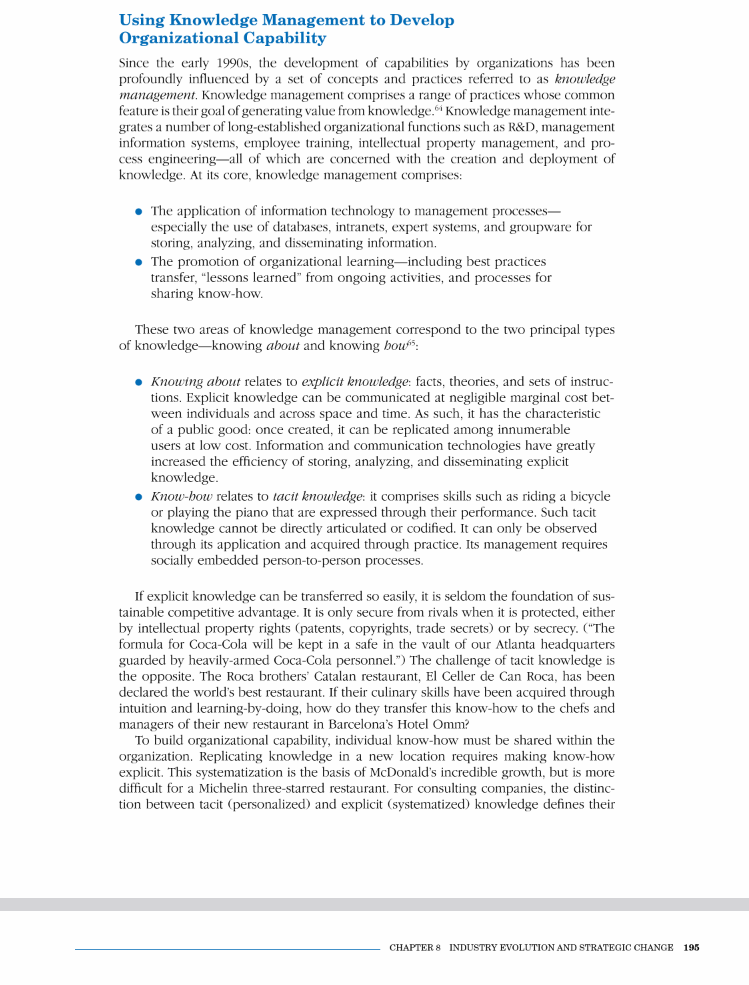

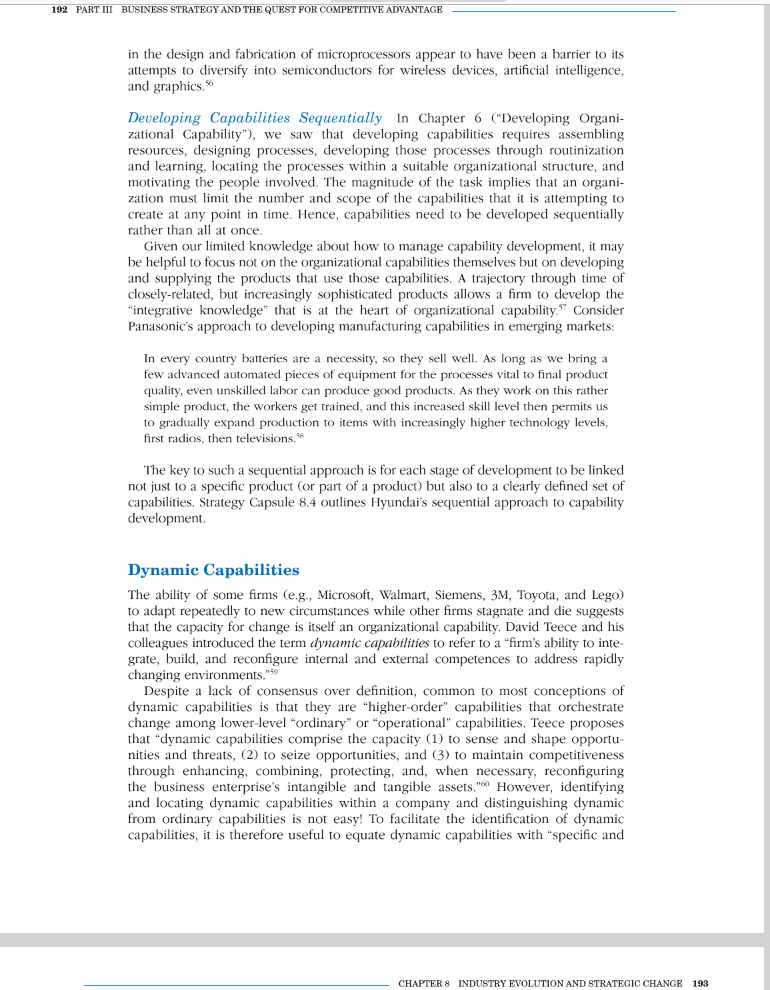

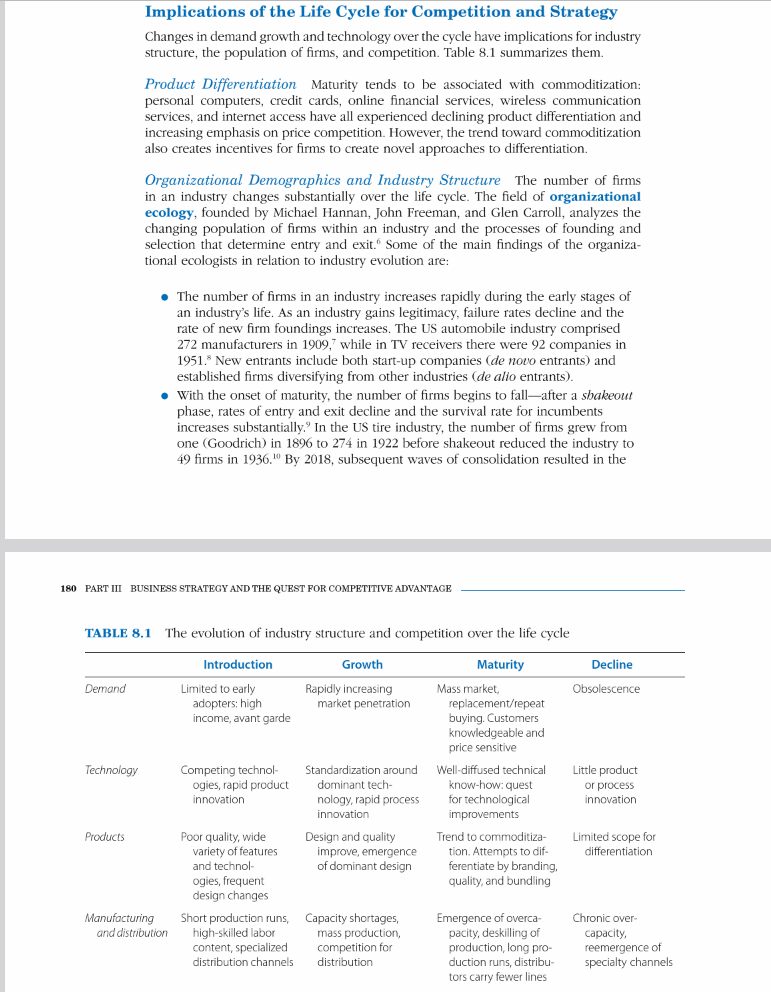

Source: Based upon I. Nonaka, "A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation," Organization Science 5 (1994): 14-37. CHAPTER 8 INDUSTRY EVOLUTION AND STRATEGIC CHANC Summary A vital task of strategic management is to navigate the crosscurrents of change. But predicting and adapting to change are huge challenges for businesses and their leaders. The life-cycle model allows us to understand the forces driving industry evolution and to anticipate their impact on industry structure and the basis of competitive advantage. But, identifying regularities in the patterns of industry evolution is of little use if firms are unable to adapt to these changes. The challenge of adaptation is huge: the presence of organizational inertia means that industry evolution occurs more through the birth of new firms and the death of old ones rather than through adaptation by established firms. Even flexible, innovative companies experience problems in coping with new technologies-especially those that are "competence destroying: "disruptive," or embody"architectural innovation." Managing change requires managers to operate in two time zones: they must optimize for today while preparing the organization for the future. The concept of the ambidextrous organization is an approach to resolving this dilemma. Other tools for managing strategic change include: creating perceptions of crisis, establishing stretch targets, corporate-wide initiatives, recruiting external managerial talent, dynamic capabilities, and scenario planning. Whatever approach or tools are adopted to manage change, strategic change requires building new capabilities. To the extent that an organization's capabilities are a product of its entire history, building new capabilities is a formidable challenge. To understand how organizations build capability, we need to understand how resources are integrated into capability-in particular, the role of processes, structure, motivation, and alignment. The complexities of capability development and our limited understanding of how capabilities are built point to the advantages of sequential approaches to developing capabilities. Ultimately, capability building is about harnessing the knowledge which exists within the organization. For this purpose, knowledge management offers considerable potential for increasing the effectiveness of capability development. In addition to specific techniques for identifying, retaining, sharing, and replicating knowledge, the knowledge-based view of the firm offers penetrating insights into the challenges of-and potential for-the creation and exploitation of knowledge by firms. In the next two chapters, we discuss strategy formulation and strategy implementation in industries at different stages of their development: emerging industries, which are characterized by rapid change and technology-based competition, and mature industries. STRATEGY CAPSULE 8.5 Knowledge Conversion and Knowledge Replication Ikujiro Nonaka's theory of knowledge creation argues that knowledge conversion between tacit and explicit forms and between individual and organizational levels produces a "knowledge spiral" in which the organization's stock of knowledge broadens and deepens. For example, explicit knowledge is internalized into tacit knowledge in the form of intuition, know-how, and routines, while tacit knowledge is externalized into explicit knowledge through articulation and codification. Knowledge also moves between levels: individual knowledge is combined into organizational knowledge; individual knowledge is socialized into organizational knowledge. Knowledge conversion lies at the heart of a key stage of business development: the transition from the croft enterprise based upon ind ividual, tacit knowledge, to the industrial enterprise based upon explicit, organizational knowledge. This transition is depicted in Figure 8.6 and is illustrated by the following examples: - Henry Ford's Model T was initially produced on a small scale by skilled workers. Ford's assembly line mass-production technology systematized that individual, tacit knowledge and built it into machines and processes. Ford's industrial system was no longer dependent upon skilled craftsmen: the assembly lines could be operated by former farm workers and new immigrants. - When Ray Kroc discovered the McDonald brothers' hamburger stand in San Bernardino, California, he recognized the potential for systematizing and replicating their process. McDonald's business model was replicated through operating manuals and training programs. Now 400,000 employees, most of whom lack the most rudimentary culinary skills, serve 68 million customers daily. The relevant knowledge is embedded within McDonald's business system. This systematization of knowledge offers massive potential for value creation through replication and deskilling. This systematization has transformed the service sector: with the replacement of individual proprietorships by international chains in hotels (Marriott), car rental (Hertz), coffee shops (Starbucks), and tax preparation (H\&R Block). FIGURE 8.6 Knowledge conversion Source: Based upon I. Nonaka, "A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation," Orgonization Science 5 (1994): 14-37. CHAPTER 8 INDUSTRY EVOLUTIONAND STRATEGIC CHANGE 197 TABLE 8.4 Knowledge management practices business model and is a central determinant of their strategy 66 Moreover, while systematization permits internal replication, it also facilitates imitation by rivals. The result is a "paradox of replication." In order to utilize knowledge to build organizational capability, we need to replicate it; and replication is much easier if the knowledge is in explicit form. 67 Knowledge Management Activities That Contribute to Capability Development Knowledge management comprises activities that contribute to capability development by building, retaining, accessing, transferring, and integrating knowledge. Table 8.4 lists several knowledge management practices. However, the role of knowledge as a basis for organizational capability extends beyond the application of specific knowledge management techniques to a view of the firm as a knowledge system. The knowledge-based view of the firm, as developed by Ikujiro Nonaka and others, offers penetrating insights into the organizational processes through which knowledge is created and deployed (see Strategy Capsule 8.5). 196 PART III BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE QUEST FOR COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE Organizational Capability Since the early 1990s, the development of capabilities by organizations has been profoundly influenced by a set of concepts and practices referred to as knowledge management. Knowledge management comprises a range of practices whose common feature is their goal of generating value from knowledge. 6i Knowledge management integrates a number of long-established organizational functions such as R\&D, management information systems, employee training, intellectual property management, and process engineering-all of which are concerned with the creation and deployment of knowledge. At its core, knowledge management comprises: - The application of information technology to management processesespecially the use of databases, intranets, expert systems, and groupware for storing, analyzing, and disseminating information. - The promotion of organizational learning-including best practices transfer, "lessons learned" from ongoing activities, and processes for sharing know-how. These two areas of knowledge management correspond to the two principal types of knowledge-knowing about and knowing bow 15 : - Knowing about relates to explicit knowledge: facts, theories, and sets of instructions. Explicit knowledge can be communicated at negligible marginal cost between individuals and across space and time. As such, it has the characteristic of a public good: once created, it can be replicated among innumerable users at low cost. Information and communication technologies have greatly increased the efficiency of storing, analyzing, and disseminating explicit knowledge. - Know-bow relates to tacit knowledge: it comprises skills such as riding a bicycle or playing the piano that are expressed through their performance. Such tacit knowledge cannot be directly articulated or codified. It can only be observed through its application and acquired through practice. Its management requires socially embedded person-to-person processes. If explicit knowledge can be transferred so easily, it is seldom the foundation of sustainable competitive advantage. It is only secure from rivals when it is protected, either by intellectual property rights (patents, copyrights, trade secrets) or by secrecy. ("The formula for Coca-Cola will be kept in a safe in the vault of our Atlanta headquarters guarded by heavily-armed Coca-Cola personnel.") The challenge of tacit knowledge is the opposite. The Roca brothers' Catalan restaurant, El Celler de Can Roca, has been declared the world's best restaurant. If their culinary skills have been acquired through intuition and learning-by-doing, how do they transfer this know-how to the chefs and managers of their new restaurant in Barcelona's Hotel Omm? To build organizational capability, individual know-how must be shared within the organization. Replicating knowledge in a new location requires making know-how explicit. This systematization is the basis of McDonald's incredible growth, but is more difficult for a Michelin three-starred restaurant. For consulting companies, the distinction between tacit (personalized) and explicit (systematized) knowledge defines their CHAPTER 8 INDUSTRY EVOLUTION AND STRATEGIC CHANGE 195 STRATEGY CAPSULE 8.4 Hyundai Motor: Developing Capabilities through Product Sequencing Hyundai's emergence as a world-class automobile producer is a remarkable example of capability development over a sequence of compressed phases (Figure 8.5). Each phase of the development process was characterized by a clear objective in terms of product outcome, a tight time deadline, an empowered development team, a clear recognition of the capabilities that needed to be developed in each phase, and an atmosphere of impending crisis should the project not succeed. The first phase was the construction of an assembly plant in the unprecedented time of 18 months in order to build Hyundal's first carma Ford Cortina imported in semi-knocked down (SKD) form. Subsequent phases involved products of increasing sophistication and the development of more advanced capabilities. FIGURE 8.5 Phased development at Hyundai Motor, 1968-1995 Source: Based on L. Km, 'Crisis Construction and Organizational Learning: Capability Building and Catching up at Hyundai Motor, Organizotional Science 9 (1998): 505-521. identifiable processes"61 and "patterned and routine" 62 behavior (as opposed to ad hoc problem solving). IBM offers an example of how management processes can build higher-level dynamic capabilities. Since 1999, IBM's Strategic Leadership Model comprises a system for identifying new business opportunities then developing them into new business initiatives (see Strategy Capsule 13.4 in Chapter 13), 63 194 PART III BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE QUEST FOR COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE I BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE QUEST FOR COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE in the design and fabrication of microprocessors appear to have been a barrier to its attempts to diversify into semiconductors for wireless devices, artificial intelligence, and graphics. 56 Developing Capabilities Sequentially In Chapter 6 ("Developing Organizational Capability"), we saw that developing capabilities requires assembling resources, designing processes, developing those processes through routinization and learning, locating the processes within a suitable organizational structure, and motivating the people involved. The magnitude of the task implies that an organization must limit the number and scope of the capabilities that it is attempting to create at any point in time. Hence, capabilities need to be developed sequentially rather than all at once. Given our limited knowledge about how to manage capability development, it may be helpful to focus not on the organizational capabilities themselves but on developing and supplying the products that use those capabilities. A trajectory through time of closely-related, but increasingly sophisticated products allows a firm to develop the "integrative knowledge" that is at the heart of organizational capability. 57 Consider Panasonic's approach to developing manufacturing capabilities in emerging markets: In every country batteries are a necessity, so they sell well. As long as we bring a few advanced automated pieces of equipment for the processes vital to final product quality, even unskilled labor can produce good products. As they work on this rather simple product, the workers get trained, and this increased skill level then permits us to gradually expand production to items with increasingly higher technology levels, first radios, then televisions, 58 The key to such a sequential approach is for each stage of development to be linked not just to a specific product (or part of a product) but also to a clearly defined set of capabilities. Strategy Capsule 8.4 outlines Hyundai's sequential approach to capability development. Dynamic Capabilities The ability of some firms (e.g., Microsoft, Walmart, Siemens, 3M, Toyota, and Lego) to adapt repeatedly to new circumstances while other firms stagnate and die suggests that the capacity for change is itself an organizational capability. David Teece and his colleagues introduced the term dynamic capabilities to refer to a "firm's ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments." 39 Despite a lack of consensus over definition, common to most conceptions of dynamic capabilities is that they are "higher-order" capabilities that orchestrate change among lower-level "ordinary" or "operational" capabilities. Teece proposes that "dynamic capabilities comprise the capacity (1) to sense and shape opportunities and threats, (2) to seize opportunities, and (3) to maintain competitiveness through enhancing, combining, protecting, and, when necessary, reconfiguring the business enterprise's intangible and tangible assets." 60 However, identifying and locating dynamic capabilities within a company and distinguishing dynamic from ordinary capabilities is not easy! To facilitate the identification of dynamic capabilities, it is therefore useful to equate dynamic capabilities with "specific and Multiple-Scenario Development at Shell Royal Dutch Shell has used scenarios as a basis for long-term strategic planning since 1967. Mike Pocock, Shell's former chairman, observed: "We believe in basing planning not on single forecasts, but on deep thought that identifies a coherent pattern of economic, political, and social development." Shell's scenarios are critical to the transition of its planning function from producing plans to leading a process of dialogue and learning, the outcome of which is improved decision making by managers. This involves continually challenging current thinking within the group, encouraging a wider look at external influences on the business, and forging coordination among Shell's 200+ subsidiaries. Shell's global scenarios are prepared every four or five years by a team comprising corporate planning staff, executives, and outside experts. Economic, political, technological, and demographic trends are analyzed up to 50 years into the future. In 2014, Shell identified two global scenarios for the period to 2060: - Mountains. A world where current elites retain their power, manage for stability, and "unlock resources steadily and cautiously, not solely dictated by immediate market forces. The resulting rigidity within the system dampens economic dynamism and stifles social mobility. - Oceans: A world of devolved power where "competing interests are accommodated and compromise is king. Economic productivity surges on a huge wave of reforms, yet social cohesion is sometimes eroded and politics destabilized... giving immediate market forces greater prominence. Once approved by top management, the scenarios are disseminated by reports, presentations, and workshops, where they form the basis for long-term strategy discussion by business sectors and operating companies Shell is adamant that its scenarios are not forecasts. They represent carefully thought-out storles of how the various forces shaping the global energy environment of the future might play out. Their value is in stimulating the social and cognitive processes through which managers envisage the future: "They are designed to stretch management to consider even events that may be only remotely possible: According to former CEO Jeroen van der veer: "the imperative is to use this tool to gain deeper insights into our global business environment and to achieve the cultural change that is at the heart of our group strategy. Sources: A. de Geus, "Planning as Learning." Harvard Business Review (March/April 1988): 70-74: P. Schoemacher, "Multiple Scenario Development: Its Conceptual and Behavioral Foundation," Strategic Management Journal 14 (1993): 193-214; Royal Dutch Shell, New Lens Scenarios: A Shift in Perspective for a Worid in Transition (2014). CHAPTER 8 INDUSTRY EVOLUTION AND STRATEGIC CHANGE 191 TABLE 8.3 Childhood experiences shape distinctive capabilities Combatting Organizational Inertia If organizational change follows a pattern of punctuated equilibrium in which periods of stability are interspersed by periods of intense upheaval, what precipitates these episodes of transformational change? Typically, corporate restructuring, involving simultaneous changes in strategy, structure, management systems, and top management personnel, is triggered by declining performance. For example, the oil and gas majors underwent far-reaching restructuring during 1986-1992 following the oil price decline of 1986.46 During 2017, consumer goods giants Unilever, Procter \& Gamble, and Nestl all initiated major restructuring programs in response to sluggish sales, declining profitability, and takeover threats. A challenge for top management is to undertake large-scale change before being pressured by declining performance. This may require managers to let go of the beliefs that wed them to the prevailing strategy. Polaroid's failure to exploit its many digital-imaging innovations can be attributed to top management's commitment to its traditional business model, 47 Creating Perceptions of Crisis Crises create the conditions for strategic change by loosening the organization's attachment to the status quo. The problem is that by the time the organization is engulfed in crisis it may already be too late. Hence, leaders may foster the perception of impending crisis so that necessary changes can be implemented well before a real crisis emerges. At General Electric, even when the company was reporting record profits, Jack Welch was able to convince employees of the need for change in order to defend against emerging threats. As CEO of Intel, Andy Grove's dictum "Only the paranoid survive" galvanized a continual striving for improvement and development despite its dominance of the microprocessor market. Establishing Stretch Targets Ambitious performance targets can help counteract organizational inertia. Stretch goals can motivate creativity and initiative while attacking complacency. Such goals are usually quantitative and short term; however, they can also be long-term qualitative goals. A key role of vision statements and strategic intent is to create a sustained sense of ambition and shared purpose. These ideas are exemplified by Collins and Porras' notion of "Big Hairy Ambitious Goals" that I discussed in Chapter 1. Apple's success in introducing "insanely great" new products owes much to Steve Jobs setting lofty goals for his product development teams. For the iPod, he insisted that it should store thousands of songs, have a battery life exceeding four hours, and be smaller and thinner than any existing MP3 player. 48 CHAPTER 8 INDUSTRY EVOLUTION AND STRATEGIC CHANGE Corporate-Wide Initiatives as Catalysts of Change By combining authoritative and charismatic leadership, CEOs can pioneer specific change initiatives with a surprisingly extensive impact. At General Electric, Jack Welch was an especially effective exponent of using corporate initiatives to drive organizational change. These were built around communicable and compelling slogans such as "Be number 1 or number 2 in your industry," "boundarylessness," "six-sigma quality," and "destroy-your-businessdot-com." Leaders can also have a profound impact through symbolic actions, A key incident in the transformation of the Qingdao Refrigerator Plant into Haier, one of the world's biggest appliance companies, was CEO, Zhang Ruimin, using a sledgehammer to destroy defective refrigerators in front of the assembled workforce., +9 Reorganizing Company Structure Corporate reorganization permits redistribution of power, reshuffling of top management, and introduction of new blood. One of the last major actions of CEO Steve Ballmer before retiring in August 2013 was to reorganize Microsoft's divisional structure in order to break down established power centers and facilitate the transition to a more integrated company, Activist investor, Managing Strategic Change Given the many barriers to organizational change and the difficulties that companies experience in coping with disruptive technologies and architectural innovation, how can companies adapt to changes in their environment? Just as the sources of organizational inertia are many, so too are the theories and methods of organizational change. Early approaches to organizational change included socio-technical systems theory, which addressed the need for social systems to adapt to the requirements of new technologies, 36 and organizational development (OD), which emphasized group dynamics and the role of "change agents." 37 Subsequently, managing change has become a central topic within strategic management. In this section, we review five approaches to managing strategic change. We begin with the challenge of managing for today while preparing for tomorrow and discuss the potential for organizational ambidexterity. Second, we examine management tools for counteracting organizational inertia. Third, we explore the means by which companies develop new capabilities. Fourth, we address the role and nature of dynamic capabilities. Finally, we examine the contribution of knowledge management. Dual Strategies and Organizational Ambidexterity In Chapter 1 , we learned that strategy has two major dimensions: positioning for the present and adapting to the future. Reconciling the two is difficult. Derek Abell argued that "managing with dual strategies"-in terms of "lavishing attention on those factors that are critical to short-term success" while "changing a business in anticipation of the future"-is the most challenging dilemma that senior managers face. 38 This challenge of reconciling "competing for today" with "preparing for tomorrow" is closely related to the tradeoff between exploitation and exploration that we discussed in relation to organizational inertia. Charles O'Reilly and Michael Tushman use the term "organizational ambidexterity" to refer to the capacity to reconcile exploration with exploitation. The ambidextrous firm is "capable of simultaneously exploiting existing competences and exploring new opportunities." 19 There are two approaches to creating organizational ambidexterity: structural and contextual. Structural Ambidexterity involves creating organizational units for exploration activities that are separate from the core operational activities of the company. to For example: - IBM developed its PC in a separate unit in Florida-far from IBM's corporate headquarters in New York. Its leader, Bill Lowe, claimed that this separation was critical to creating a business system that was radically different from IBM's vertically integrated mainframe business. i1 - Shell's GameChanger program was established as a separate unit to develop new avenues for growth by exploiting innovations and entrepreneurial initiatives that would otherwise be stifled by Shell's financial system and organizational structure, 12 188 PART III BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE QUEST FOR COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE The key challenge is to ensure that the initiatives fostered within the "exploration" unit Coping with Technological Change Competition between new start-ups and established firms is not restricted to the early phases of an industry's life cycle: it is ongoing. Technological change can greatly assist newcomers to unseat incumbent firms. The strategy literature suggests that new technology is especially threatening when it is "competence destroying," "architectural," or "disruptive." Competence Enhancing and Competence Destroying Technological Change Some technological changes undermine the resources and capabilities of established firms; they are "competence destroying." Other changes are "competence enhancing" they preserve, even strengthen, the resources and capabilities of incumbent firms.." The quartz watch radically undermined the competence base of mechanical watchmakers. Conversely, the turbofan, a major advance in jet engine technology, reinforced the capability base of existing aero engine manufacturers. Architectural and Component Innovation The ease with which established firms adapt to technological change depends upon whether the innovation occurs at the component or the arcbitectural level. Innovations that change the overall architecture of a product create great difficulties for established firms because they require reconfiguration of a company's entire business system. 31 In automobiles, the hybrid engine was an important innovation but did not require a major reconfiguration of car design and engineering. The plug-in electric motor is an architectural innovation-it requires redesign of the entire car and networks of charging stations. In grocery retailing, e-commerce provides an additional channel for distributing existing products, without requiring a complete reconfiguration of supply chains. Hence, e-commerce represents a component rather than an architectural innovation and, to date, existing supermarket chains with their "clicks and bricks" business models are dominating online groceries. 32 Disruptive Technologies Clay Christiansen distinguishes between new technology that is sustaining - it augments existing performance attributes-and new technology that is disruptive-it incorporates different performance attributes than the existing technology. 33 These disruptive technologies are ignored by established firms because they are initially inferior. However, their rate of improvement is faster than for the established technology; as a result, the new firms that pioneer them can overtake the incumbents. Steam-powered ships were introduced at the beginning of the 19 th century, but were initially slower, more expensive, and less reliable than sailing ships. The leading shipbuilders did not adopt steam power because their leading customers, the transoceanic shipping companies, remained loyal to sail until the 1880 s. Steam power was used mainly for inland waters, which lacked constant winds. After several decades of development, steam-powered ships were able to outperform sailing ships on ocean routes, 31 Similarly, minimills initially produced inferior-quality steel to integrated steel plants; digital images were much lower resolution than film images; solar and wind power were more expensive than gas and coal generation. Yet, over time, the new technologies overtook the older technologies 35 Sources: L. Hannah, "Marshall's 'Trees' and the Global 'Forest': Were 'Glant Redwoods' Different?' in N. Lamoreaux, D. Raff, and P. Temin (eds.), Leaming by Doing in Markets, Firms and Nations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999): 253-294; Financial Times (March 5, 2021). and these established incumbents offer the financial resources and functional capabilities needed to grow start-ups. In plant biotechnology, the pioneers were start-ups such as Calgene, Cetus Corporation, DNA Plant Technologies, and Mycogen; by 2020, the leading suppliers of genetically modified seeds were Bayer (which acquired Monsanto) and ChemChina (which acquired Syngenta)_both long-established chemical firms. Of course, some start-ups do survive and become industry leaders: Google, Cisco Systems, and Facebook are examples. Geoffrey Moore describes the transition from a start-up serving early adopters to an established business serving mainstream customers as "crossing the chasm." 26 In most new industries, we find a mixture of start-up companies (de novo entrants) and established companies that have diversified from other sectors (de alio entrants). Which is more successful depends upon whether the flexibility and entrepreneurial advantages of start-ups outweigh the superior resources and capabilities of established firms. This further depends upon whether the resources and capabilities required in the new industry are similar to those present in an existing industry. Where these linkages are close, de alio entrants are at an advantage. In automobiles, former bicycle, carriage, and engine manufacturers tended to be the best performers 27 Production of television sets in the US became dominated by former producers of radios. 28 Many start-up ventures are established by former employees of established firms within the same sector. In Silicon Valley, most of the leading semiconductor firms, including Intel, trace their origins to Shockley Semiconductor Laboratories, the pioneer of integrated circuits. 29 Established companies are important investors in new ventures. Some of the world's biggest venture capitalists are technology giants such as Alphabet, SoftBank, Salesforce, Baidu, and Intel. 186 PART III BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE QUEST FOR COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE Coping with Technological Change Thinking about industrial and organizational change has been strongly influenced by ideas from evolutionary biology. Evolutionary change is an adaptive process that involves variation, selection, and retention, 21 Evolution occurs at the level of both the industry and the firm: - Organizational ecology has been discussed in relation to changes in the number of firms in an industry over time. However, organizational ecology is a broader theory of economic change. Organizational inertia implies that industry evolution occurs through changes in the population of firms rather than by adaptation of firms themselves. The competitive process is a selection mechanism, in which organizations whose characteristics match the requirements of their environment can attract resources; those that do not are eliminated. Successful firms are then replicated through imitation, 22 - Evolutionary economics emphasizes change within individual firms. The processes of variation, selection, and retention take place at the level of the organizational routine - unsuccessful routines are abandoned; successful routines are retained and replicated within the organization. 23 As we discussed in Chapter 5 , these patterns of coordinated activity are the basis for organizational capability. Firms evolve through searching for new routines, replicating successful routines, and abandoning unsuccessful routines. While the membership of most industries changes dramatically over time, some firms show a remarkable capacity for adaptation. BASF has been one of the world's leading chemical companies since it began producing synthetic dyes in 1865. Exxon and Shell have led the world's petroleum industry since the late 19 th century. 24 Mitsui Group, a Japanese conglomerate, is even older-its first business, a retail store, was established in 1673. Yet these companies are exceptions. Among the companies forming the original Dow Jones Industrial Average in 1896, only General Electric remained in the index until it was dropped in 2018. Of the world's 12 biggest companies in 1912, none remained in the top 12 by 2020 (Table 8.2). And life spans are shortening: the average period in which companies remained in the S\&P 500 was 90 years in 1935 ; in 1958 it was 61 years; by 2020 it was down to 15 years. The demise of great companies partly reflects the rise of new industries-notably the information and communications technology (ICT) sector, but also the failure of established firms to adapt successfully to the life cycles of their own industries. Even if the pattern of industry evolution can be predicted, different stages of the life cycle require different resources and capabilities. The innovators that pioneer the creation of a new industry are typically different companies from the "consolidators" that develop it: The skills, mind-sets, and competences needed for discovery and invention are not only different from those needed for commercialization; they conflict with the needed characteristics. This means that the firms good at invention are unlikely to be good at commercialization and vice versa, 25 The typical pattern is that technology-based start-ups that pioneer new areas of business are acquired by companies that are well established in closely related industries, CHAPTER 8 INDUSTRY EVOLUTION AND STRATEGIC CHANGE 185 We have established that industries change. But what about the companies within them? Let us turn our attention to business enterprises and consider both the impediments to change and the means by which change takes place. Why Is Change So Difficult? The Sources of Organizational Inertia At the heart of all approaches to change management is the recognition that organizations find change difficult. Why is this so? Different theories of organizational and industrial change emphasize different barriers to change: - Organizational routines: Evolutionary economists emphasize the fact that capabilities are based on organizational routines-patterns of coordinated interaction among organizational members that develop through continual repetition. The more highly developed are an organization's routines, the more difficult it is to develop new routines. Hence, organizations get caught in competency traps 12 where "core capabilities become core rigidities."13 - Social and political structures: Organizations are both social systems and political systems. As social systems, organizations develop patterns of interaction that make organizational change stressful and disruptive. 14 As political systems, organizations develop stable distributions of power; change represents a threat to the power of those in positions of authority. Hence, both as social systems and political systems, organizations resist change. - Conformity: Institutional sociologists emphasize the propensity of firms to imitate one another in order to gain legitimacy. This process of institutional isomorphism locks organizations into common structures and strategies that resist change. 15 Such imitation is a form of risk aversion. 16 External actorsgovernments, investment analysts, banks, and other resource providers-also encourage conformity of strategies and structures. - Limited searcb: The Carnegie School of organizational theory (associated with Herbert Simon, Jim March, and Richard Cyert) views search as the primary source of organizational change. Organizations tend to limit search to areas close to their existing activities-they prefer exploitation of existing knowledge over exploration for new opportunities 17 Limited search is reinforced, first, by bounded rationality_human beings have limited information processing capacity, which constrains the set of choices they can consider and, second, by satisficing - the propensity for individuals (and organizations) to terminate the search for better solutions when they reach a satisfactory level of performance rather than to pursue optimal performance. Hence, crisis tends to be a prerequisite for major organizational change. - Complementarities between strategy, structure, and systems: We encountered the notion of strategic fit in Chapter 1. A firm's strategy must fit its external CHAPTER 8 INDUSTRY EVOLUTION AND STRATEGIC CHANGF environment and its internal resources and capabilities. Moreover, all the components of a firm's strategy must fit together: we observed that strategy is manifest as an activity system. Ultimately, all the features of an organization-strategy, structure, systems, culture, goals, and employee skills-are complementary. 18 Organizations establish combinations of strategy, processes, structures, and management styles during their early phases of development that are shaped by the cir- Implications of the Life Cycle for Competition and Strategy Changes in demand growth and technology over the cycle have implications for industry structure, the population of firms, and competition. Table 8.1 summarizes them. Product Differentiation Maturity tends to be associated with commoditization: personal computers, credit cards, online financial services, wireless communication services, and internet access have all experienced declining product differentiation and increasing emphasis on price competition. However, the trend toward commoditization also creates incentives for firms to create novel approaches to differentiation. Organizational Demographics and Industry Structure The number of firms in an industry changes substantially over the life cycle. The field of organizational ecology, founded by Michael Hannan, John Freeman, and Glen Carroll, analyzes the changing population of firms within an industry and the processes of founding and selection that determine entry and exit. 6 Some of the main findings of the organizational ecologists in relation to industry evolution are: - The number of firms in an industry increases rapidly during the early stages of an industry's life. As an industry gains legitimacy, failure rates decline and the rate of new firm foundings increases. The US automobile industry comprised 272 manufacturers in 19099,while in TV receivers there were 92 companies in 1951.8 New entrants include both start-up companies (de novo entrants) and established firms diversifying from other industries (de alio entrants). - With the onset of maturity, the number of firms begins to fall-after a sbakeout phase, rates of entry and exit decline and the survival rate for incumbents increases substantially. In the US tire industry, the number of firms grew from one (Goodrich) in 1896 to 274 in 1922 before shakeout reduced the industry to 49 firms in 1936. 10 By 2018 , subsequent waves of consolidation resulted in the 180 PART III BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE QUEST FOR COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE TABLE 8.1 The evolution of industry structure and competition over the life cycle The Industry Life Cycle One of the best-known and most enduring marketing concepts is the product life cycle. 1 Products are born, their sales grow, they reach maturity, they go into decline, and they ultimately die. If products have life cycles, so the industries that produce them experience an industry life cycle. To the extent that an industry produces multiple generations of a product, the industry life cycle is likely to be of longer duration than that of a single product. The life cycle comprises four phases: introduction (or emergence), growth, maturity, and decline (Figure 8.1). Let us first examine the forces that drive industry evolution, and then look at the features of each of these stages. Two forces are fundamental: demand growth and the production and diffusion of knowledge. Demand Growth The life cycle and the stages within it are defined primarily by changes in an industry's growth rate over time. The characteristic profile is an S-shaped growth curve. - In the introduction stage, sales are small and the rate of market penetration is low because the industry's products are little known and customers are few. The novelty of the technology, small scale of production, and lack of experience mean high costs and low quality. Customers for new products tend to be affluent, tech-savvy, and risk-tolerant. - The growth stage is characterized by accelerating market penetration as technical improvements and increased efficiency open up the mass market. - Increasing market saturation causes the onset of the maturity stage. Once saturation is reached, demand is wholly for replacement. - Finally, as new substitute products appear, the industry enters its decline stage. Creation and Diffusion of Knowledge The second driver of the industry life cycle is knowledge. New knowledge, in the form of innovation, is responsible for an industry's birth, and the dual processes of knowledge creation and knowledge diffusion propel industry evolution. FIGURE 8.1 The industry life cycle

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts