Question: From the case above, Explain: - Explain the concept of teamwork and leadership The value of teams Teamwork dilemmas Model of team effectiveness Virtual teams

From the case above, Explain:

- Explain the concept of teamwork and leadership

- The value of teams

- Teamwork dilemmas

- Model of team effectiveness

- Virtual teams

- Teams characteristics

- Team process

- Managing team conflict

- Explain the concept of financial management:

- The meaning of control

- Philosophy of control

- Total quality management

- Budgetary control

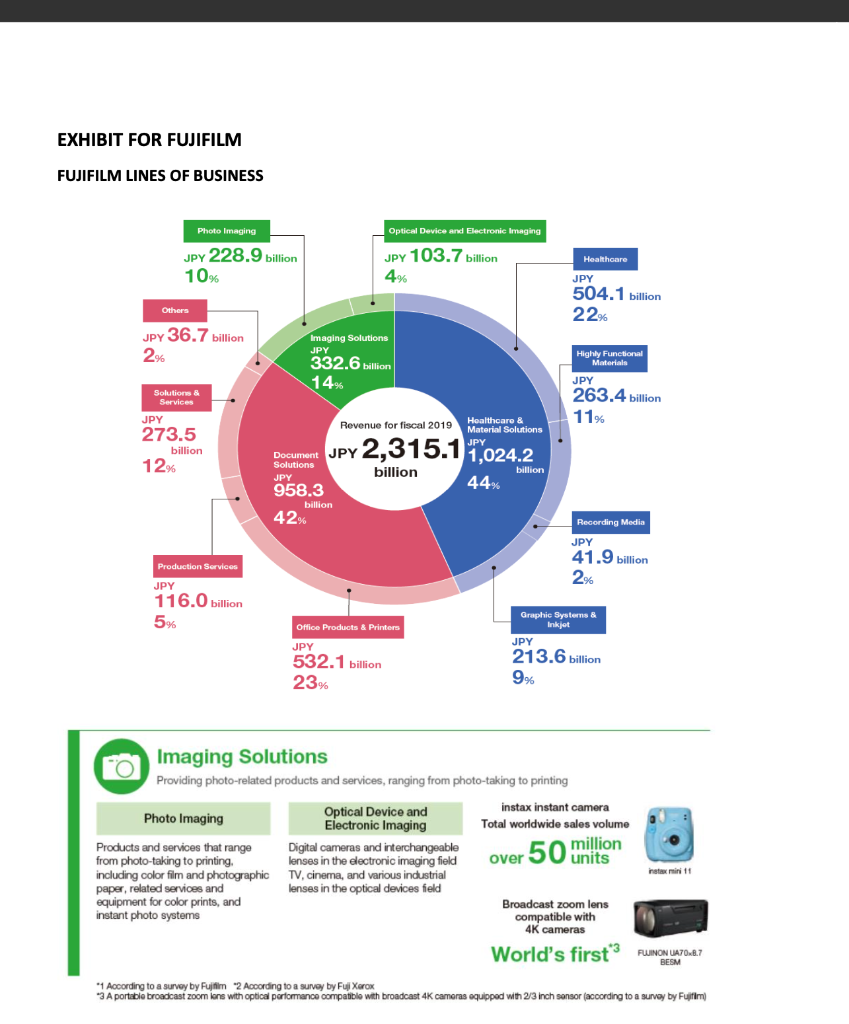

- Financial control

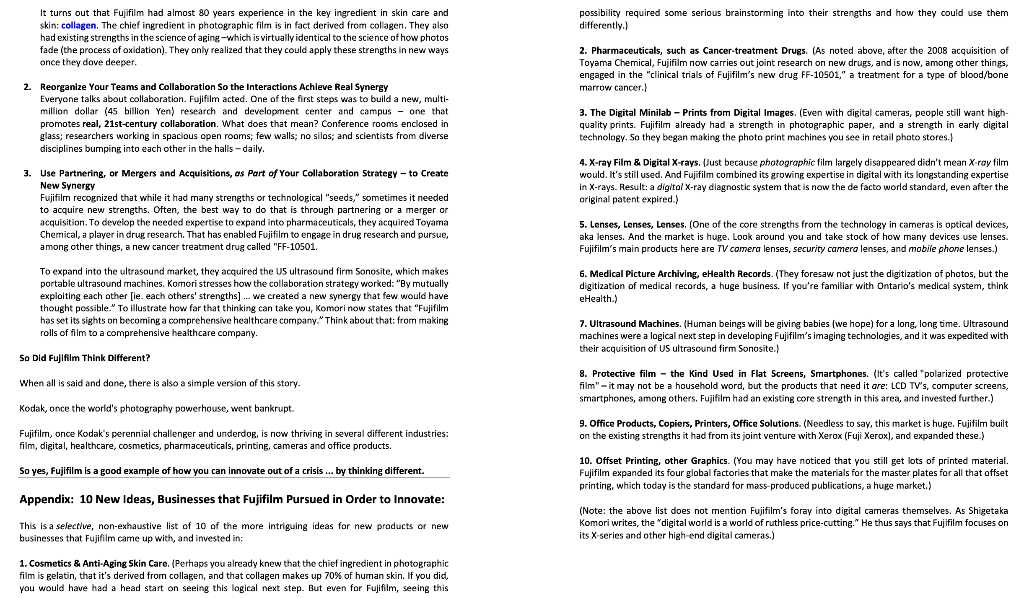

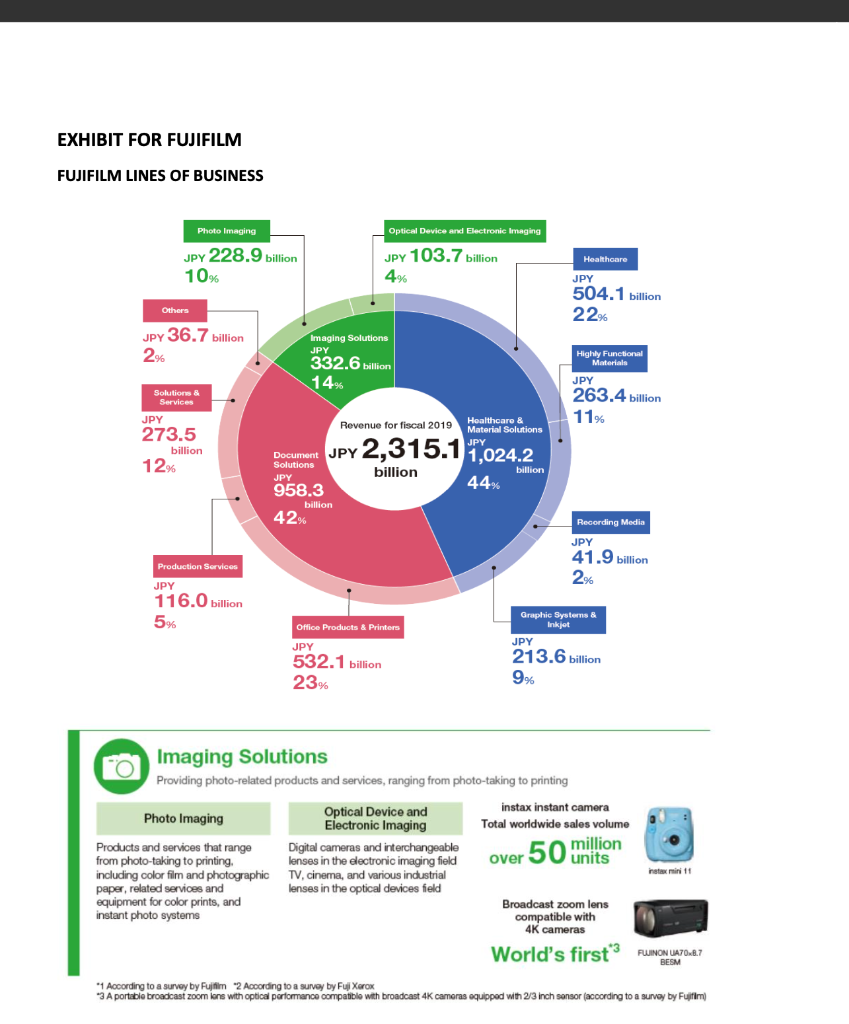

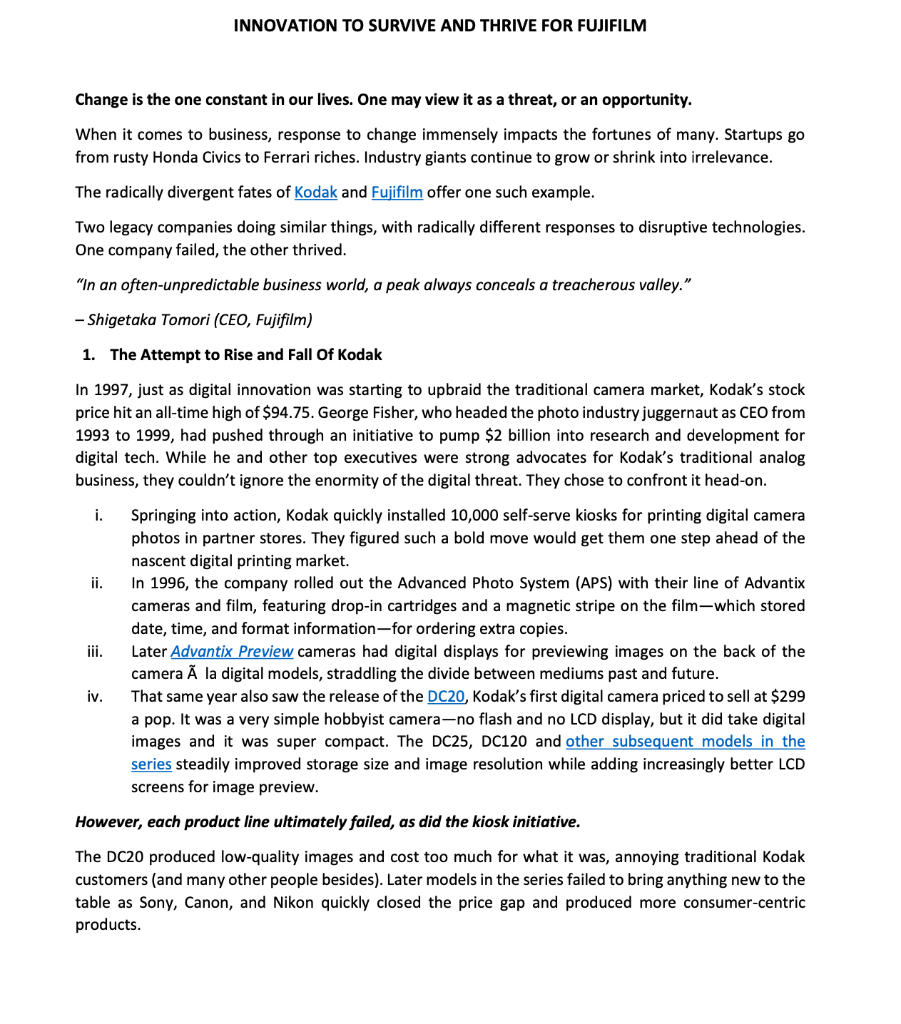

INNOVATION TO SURVIVE AND THRIVE FOR FUJIFILM Change is the one constant in our lives. One may view it as a threat, or an opportunity. When it comes to business, response to change immensely impacts the fortunes of many. Startups go from rusty Honda Civics to Ferrari riches. Industry giants continue to grow or shrink into irrelevance. The radically divergent fates of Kodak and Fujifilm offer one such example. Two legacy companies doing similar things, with radically different responses to disruptive technologies. One company failed, the other thrived. "In an often-unpredictable business world, a peak always conceals a treacherous valley." - Shigetaka Tomori (CEO, Fujifilm) 1. The Attempt to Rise and Fall Of Kodak In 1997, just as digital innovation was starting to upbraid the traditional camera market, Kodak's stock price hit an all-time high of $94.75. George Fisher, who headed the photo industry juggernaut as CEO from 1993 to 1999, had pushed through an initiative to pump $2 billion into research and development for digital tech. While he and other top executives were strong advocates for Kodak's traditional analog business, they couldn't ignore the enormity of the digital threat. They chose to confront it head-on. i. ii. iii. Springing into action, Kodak quickly installed 10,000 self-serve kiosks for printing digital camera photos in partner stores. They figured such a bold move would get them one step ahead of the nascent digital printing market. In 1996, the company rolled out the Advanced Photo System (APS) with their line of Advantix cameras and film, featuring drop-in cartridges and a magnetic stripe on the film-which stored date, time, and format information-for ordering extra copies. Later Advantix Preview cameras had digital displays for previewing images on the back of the camera la digital models, straddling the divide between mediums past and future. That same year also saw the release of the DC20, Kodak's first digital camera priced to sell at $299 a pop. It was a very simple hobbyist camera-no flash and no LCD display, but it did take digital images and it was super compact. The DC25, DC120 and other subsequent models in the series steadily improved storage size and image resolution while adding increasingly better LCD screens for image preview. iv. However, each product line ultimately failed, as did the kiosk initiative. The DC20 produced low-quality images and cost too much for what it was, annoying traditional Kodak customers (and many other people besides). Later models in the series failed to bring anything new to the table as Sony, Canon, and Nikon quickly closed the price gap and produced more consumer-centric products. The Advantix, meanwhile, never really managed to find an audience. It tried to please digital and film advocates alike, and ended up pleasing no one in particular. Case in point, these days a Google search for Advantix is more likely to turn up some exciting dog flea and tick control products. Digital kiosks didn't really jive with what most consumers wanted either, which turned out to be printing at home. That need was filled by a range of ever-cheaper inkjet printers from Hewlett-Packard, Xerox, and others. As the 21st century kicked off, Kodak pumped more and more money into digital research and tried to poach top talent from competitors. Ironically, a lot of the disruptive technologies they were confrontine (at increasing desperation) in the market had actually first been developed in-house, then shelved. They kept trying, but it was simply too late. Kodak was attempting to catch up in every field they tried to compete in-from image storage to inkjet printers to digital cameras and medical imaging technology. In fact, a Kodak engineer in the 1970s named Steve Sassoon actually created the prototype for the first digital camera way back in 1975. However, management failed to see its massive disruptive potential and make coherent long-term plans to capitalize on their innovation. In January 2018, Kodak jumped the shark completely by announcing an ICO (initial coin offering) for their own cryptocurrency, designed to protect digital photographer copyrights on the blockchain. It's called KodakCoin, and designed to work on the KODAKOne platform. As this cringe trailer suggests, it's headed straight to the crypto graveyard. . Over just the last four years, Kodak's stock price has gone into a death spiral, falling from a peak of $36.88 to around $2.70 a share. It's a phenomenal, and frankly quite sad decline for a company that did much to define how we saw the world, and even space, this past century. The edgelord strategy failed. In February 2012, Kodak announced it would stop making cameras, something they'd been doing for a whopping 110 years. They also filed for bankruptcy. 2. What Fujifilm did to save itself, and why it worked "The company's core photographic film market was shrinking at a spectacular rate, and the situation was critical. Fujifilm had good management resources, first-rate technology, a sound financial footing, a reputable brand, and excellence in its diverse workforce. If all these assets could be effectively combined into a successful strategy and applied, I was sure that something could be done to save the day." - Shigetaka Tomori CEO of Fujifilm As America's Kodak dug itself into deeper trouble, across the Pacific, Japan's Fujifilm was reinventing itself and rising to meet the digital challenge in surprising ways. Founded in 1934, Fujifilm had an almost complete monopoly on film in Japan for several decades (aka a 70%+ market share). Then in the 1980s, digital imaging technology began to register as a credible threat to the company's traditional business. They weighed the possibilities and chose to try their best to pivot and embrace change, rather than fight against the tide. Fujifilm quickly released the world's first digital camera in 1988, the FUJIX-DS1P. It was absolutely revolutionary, storing images on a semiconductor memory card. However, it was also prohibitively expensive, and personal computers hadn't yet advanced to the point of letting people do their own photo editing. So the cutting edge camera didn't exactly sell like hot cakes. Moving forward into the 1990s, Fujifilm's conventional film business actually continued to grow. Analog film products were getting better and cheaper while digital tech moved in fits and starts. Case in point, the company's QuickSnap disposable camera, introduced in 1986, became an enduring hit globally. It retailed for about $6 (a steal of a deal relative to all the $200+ USD traditional film cameras out there at the time), weighed next to nothing, and produced decent pictures. As a consequence of traditional photo film's continued, and oddly enough, increasing profitability, management began to discredit the magnitude and speed of the digital threat. By the end of the 20th century, Fujifilm eclipsed Kodak as the market leader in film and 2000 was the year that global demand for film products reached its all-time peak. But despite the milestones, the company's forecasting predicted turbulent times ahead-a contracting market for film and the end of a long era of massive profitability Then all at once, in 2003, the digital tide finally hit hard. Two-thirds of the company's traditional business was wiped out. Once popular film kiosks quickly went from processing 5,000 rolls of a film a day lon average) to 1,000 or less. Fujifilm elected a new CEO, Shigetaka Komori, and went into crisis mode. If they couldn't find their footing in the digital era fast, they were done for. Komori details how the company dramatically retooled in his book, Innovating Out of Crisis: How Fullfilm Survived land Thrived) as its Core Business was Vanishing, To avoid going under in short order, Komori oversaw the difficult decision to shutter most film manufacturing plants and downsize the company. Fujifilm cut 5,000+ jobs and lowered operating costs by $500 million. With a bit of breathing room secured, he resolved to make the business profitable under a new technology-driven direction He decided the company needed to capitalize on its scientific assets. Fujifilm had developed a vast array of chemical compounds (approximately 20,000 of them) over the years. These were now taken out of their original film photography research context and redeployed in other industries, namely pharmaceuticals, healthcare, and cosmetics. When this changeover began, it seemed like madness to some employees. After years working on film products, entire departments now found themselves devoted to beauty products and moisturizer creams. i. Fujifilm launched Astalift a line of anti-aging skincare products that promise to give you "photogenic beauty" (how fitting). All the products are based on anti-color fading technology originally applied to film conservation. Rather ingeniously, the company's lab team discovered these compounds also had similar positive effects on skin, helping to prevent saeeing and fading, Fujifilm's pharmaceutical division, meanwhile, used the company's lab infrastructure to develop new drugs. The company conducts research on cancer, Alzheimer's, and a host of other diseases, while also developing new viral vaccines and gene therapies, In the high-tech field, the company's wide arc of research and development has found unexpectedly diverse medical applications. These include digital x-ray diagnostics systems, mammography, and medical informatics. ii. iii. Healthcare and cosmetics now contribute a significant share of Fujifilm's annual income, about $3.4 Billion USD in all. By contrast, in 2017, less than 1% of Fujifilm's profits came from traditional film photography products. However, Komori states they will never abandon this aspect of their business. Possibly for good reason, as the Fujifilm instax instant camera has been mounting a quiet comeback with a new, aesthetically aware product line. Going against the prevalent wisdom of image sharing in the social media era, the line has found devoted followers among young, savvy social networkers and nostalgic old shutterbugs alike. Fujifilm took a definite risk pushing instant film cameras, especially after rival Polaroid stopped making film products in 2008. Nonetheless, it seems that after digital camera market saturation, people are discovering or re-discovering the joy of soft analog images and tangible, physical media. 2015 saw 5 million instax units sold, while sales in North America and Europe have doubled year after year since 2014. Moreover, according to earnings figures from 2018, Fujifilm's film business is now beating out digital when it comes to increasing the company's bottom line in imaging products. Is digital...over? Currently, the company's overall annual revenues are around $21.4 billion. Not too shabby for a company many had expected to die. 3. The dramatically divergent fates of Kodak and Fujifilm At the start of the 1960s, Kodak had 10 times the revenue of Fujifilm. Half a century later, Kodak is on life support and Fujifilm is doing just fine, thank you very much. The usual comparison story is that Kodak failed to adapt to the late 90s drift into digital, while Fujifilm set a new course, innovated, survived, and thrived. In this framework, the case of Kodak vs. Fujifilm is an example of the latter's ability to overcome the stubbornness of institutional memory, the "this is what we do and why we're great" mentality and aversion to change. Kodak, meanwhile, is seen as the lumbering, arrogant juggernaut; that old man telling the youngsters to shape up and do things the old timey way. But as we've learned, that's really not the whole picture. Exploring new, unexpected applications for technology and products allowed the Japanese company to re-deploy its enormous assets and conquer new markets. One can see that Kodak fought tooth and nail to also try and adapt to the digital changeover. The problem is they fought in exactly the wrong way, committing resources aggressively and too soon. They invested in digital cameras, Inkjet printers, and all the other markets that were a race to the bottom, as new competitors emerged and flooded the market with increasingly low-cost products. Ultimately, the American company failed to understand many things, including the shift away from photo kiosks to printing at home, the move from physical to electronic storage of images on computers, and people's desire to share a lot of their snapshots online-without bothering to create a physical copy of each image. Fujifilm made mistakes too, but the company's management knew when to cut losses and try something else. They released the first consumer digital camera, sure, but when they saw it wasn't selling, they didn't keep releasing it iteration after iteration (as Kodak had done with its DC20 and later models). Later on, in the early 2000s when radically intensified competition saw Sony, Nikon, Canon, and so on getting the leg up in the digital camera market, Fujifilm slowly gave up and pulled out of the fight. As Komori notes in his book, many of Fujifilm's early 2000s spin-off ventures blew up on the launch pad. But rather than try try again each time, they were generally allowed to fail. In other words, Fujifilm displayed a growth mindset that accommodated learning, innovation, and screwing up. In doing so, they cultivated and nurtured the organization's innate talents and found new ways to express them. Kodak, meanwhile, displayed a distinctively fixed mindset. At an institutional level, they kept trying to prove themselves with over-assertive actions, showing they could win big the way they always used to win. The company's organizational inflexibility and lack of careful, iterative decision making may well have been caused by its leadership's inability to overcome a fixed identity of being on top. If you prefer another analogy-Fujifilm acted like the shrewd investor who opens positional trades at different price levels, leveraging risk and the possibility of a further market downturn. Kodak bet the whole farm over a series of risky plays but unfortunately didn't manage to pull off a Hail Mary- Fujifilm may well represent an example of growth hacking at its finest. The legacy company found a way to reinvent its business and find value iteratively, in the manner of a new upstart (albeit one attached to a massive existent infrastructure). Kodak, meanwhile, tried to understand market changes and react, but it did so in broad sweeping gestures, rather than drilling down and exploring new forms of value. The company seemingly couldn't shake the memory of its dominant position in the camera/image market, and in turn, made a series of expensive strategic errors that eventually brought down the company. Change will come and with it new challenges and opportunities for sustainable growth and value delivery. As demonstrated by Fujifilm, a dose of humility and a willingness to adapt are a good starting point for continued survival and success Who would ever have thought that a company making rolls of film would one day be making cancer- treatment drugs? Or how about cosmetics? But those are just two examples of what Fujifilm has done. There are many lessons one can draw from Fujifilm's story and Mr. Komori's chronicle. Here are three big lessons that really stand out - and that we can all benefit from: 1. Look at Your Existing Strengths as the Starting point for New Possibilities You likely have great untapped strengths (both within yourself and in your company that you can probably start applying in new ways. Here's how Komori describes it: 'We needed to ascertain Fujifilm's particular strengths, which he called the company's technological "seeds." He then had his team invest months to "compare these seeds with the demands of the international market and review the results." The result was an elaborate "quadrant map to help blaze new trails." That quadrant map led the company to explore a whole range of new technologies and new markets. In other words, how do you take your existing strengths, and apply them in new ways to meet the new demands of a changing world? In other words, how do you think different? One of the most creative examples is how they moved from photographic film into cosmetics. From film to cosmetics? How do you do that? possibility required some serious brainstorming into their strengths and how they could use them differently.) It turns out that Fujifilm had almost 80 years experience in the key ingredient in skin care and skin: collagen. The chief ingredient in photographic film is in fact derived from collagen. They also had existing strengths in the science of aging-which is virtually identical to the science of how photos fade (the process of oxidation). They only realized that they could apply these strengths in new ways once they dove deeper. 2. Pharmaceuticals, such as Cancer treatment Drugs. (As noted above, after the 2008 acquisition of Toyama Chemical, Fujifilm now carries out joint research on new drugs, and is now, among other things, engaged in the "clinical trials of Fujifilm's new drug FF-10501," a treatment for a type of blood/bone marrow cancer.) 2. Reorganize Your Teams and Collaboration so the Interactions Achieve Real Synergy Everyone talks about collaboration. Fujifilm acted. One of the first steps was to build a new, multi- million dollar (45 billion Yen) research and development center and campus - one that promotes real, 21st century collaboration. What does that mean? Conference rooms enclosed in glass; researchers working in spacious open rooms; few walls; no silos; and scientists from diverse disciplines bumping into each other in the halls-daily. 3. The Digital Minilab - Prints from Digital Images (Even with digital cameras, people still want high- quality prints. Fujifilm already had a strength in photographic paper, and a strength in early digital technology, So they began making the photo print machines you see in retail photo stores.) 4. X-ray Film & Digital X-rays. Just because photographic film largely disappeared didn't mean X-ray film would. It's still used. And Fujifilm combined its growing expertise in digital with its longstanding expertise in X-rays. Result: a digital X-ray diagnostic system that is now the de facto world standard, even after the original patent expired.) 3. Use Partnering, or Mergers and Acquisitions, as part of Your Collaboration Strategy - to Create New Synergy Fujifilm recognized that while it had many strengths or technological "seeds," sometimes it needed to acquire new strengths. Often, the best way to do that is through partnering or a merger or acquisition. To develop the needed expertise to expand into pharmaceuticals, they acquired Toyama Chemical, a player in drug research. That has enabled Fujifilm to engage in drug research and pursue, among other things, a new cancer treatment drug called "FF-10501. 5. Lenses, Lenses, Lenses. (One of the core strengths from the technology in cameras is optical devices, aka lenses. And the market is huge. Look around you and take stock of how many devices use lenses. Fujifilm's main products here are TV camera lenses, security camera lenses, and mobile phone lenses.) To expand into the ultrasound market, they acquired the US ultrasound firm Sonosite, which makes portable ultrasound machines. Komori stresses how the collaboration strategy worked: "By mutually exploiting each other [ie. each others' strengths) ....We created a new synergy that few would have thought possible." To illustrate how far that thinking can take you, Komori now states that "Fujifilm has set its sights on becoming a comprehensive healthcare company." Think about that: from making rolls of film to a comprehensive healthcare company 6. Medical Picture Archiving, eHealth Records. (They foresaw not just the digitization of photos, but the digitization of medical records, a huge business. If you're familiar with Ontario's medical system, think eHealth.) 7. Ultrasound Machines. (Human beings will be giving babies (we hope) for a long, long time. Ultrasound machines were a logical next step in developing Fujifilm's imaging technologies, and it was expedited with their acquisition of US ultrasound firm Sonosite. So Did Fujifilm Think Different? When all is said and done, there is also a simple version of this story Kodak, once the world's photography powerhouse, went bankrupt. 8. Protective film - the kind Used in Flat Screens, Smartphones. (It's called "polarized protective film" - it may not be a household word, but the products that need it are: LCD TV's, computer screens, smartphones, among others. Fujifilm had an existing core strength in this area, and invested further.) 9. Office Products, Copiers, Printers, Office Solutions. (Needless to say, this market is huge. Fujifilm built on the existing strengths it had from its joint venture with Xerox (Fuji Xerox), and expanded these.) Fujifilm, once Kodak's perennial challenger and underdog, is now thriving in several different industries: film, digital, healthcare, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, printing, cameras and office products. So yes, Fujifilm is a good example of how you can innovate out of a crisis ... by thinking different. 10. Offset Printing, other Graphics. (You may have noticed that you still get lots of printed material. Fujifilm expanded its four global factories that make the materials for the master plates for all that offset printing, which today is the standard for mass-produced publications, a huge market.) Appendix: 10 New Ideas, Businesses that Fujifilm Pursued in order to Innovate: This is a selective, non-exhaustive list of 10 of the more intriguing ideas for new products or new businesses that Fujifilm came up with, and invested in: (Note: the above list does not mention Fujifilm's foray into digital cameras themselves. As Shigetaka Komori writes, the "digital world is a world of ruthless price-cutting." He thus says that Fujifilm focuses on its X-series and other high-end digital cameras.) 1. Cosmetics & Anti-Aging Skin Care. (Perhaps you already knew that the chief ingredient in photographic film is gelatin, that it's derived from collagen, and that collagen makes up 70% of human skin. If you did, you would have had a head start on seeing this logical next step. But even for Fujifilm, seeing this EXHIBIT FOR FUJIFILM FUJIFILM LINES OF BUSINESS Photo Imaging Optical Device and Electronic Imaging JPY 228.9 billion 10% JPY 103.7 billion 4% Healthcare JPY 504.1 billion 22% Others JPY 36.7 billion 2% Imaging Solutions JPY 332.6 billion 14% Highly Functional Materials JPY 263.4 billion 11% Solutions & Services Revenue for fiscal 2019 JPY 273.5 billion 12% Healthcare & Material Solutions JPY Solutions JPY billion billion 44% 958.3 billion 42% Recording Media JPY 41.9 billion 2% Production Services JPY 116.0 billion 5% Office Products & Printer JPY Graphic Systerns & Inkjet JPY 213.6 billion 9% 532.1 billion 23% Imaging Solutions Providing photo-related products and services, ranging from photo-taking to printing instax instant camera Total worldwide sales volume million Optical Device and Electronic Imaging Digital cameras and interchangeable lenses in the electronic imaging field , cinema, and various industrial lenses in the optical devices field Photo Imaging Products and services that range from photo taking to printing, including color film and photographic paper, related services and equipment for color prints, and instant photo systems over 50 unitis instax mini 11 Broadcast zoom lens compatible with 4K cameras World's first FUJINON UA70.8.7 BESM *1 According to a survey by Fujifilm 2 According to a survey by Fuji Xerox 3 A portable broadcast zoom ions with optical performance compatible with broadcast 4K cameras equipped with 2/3 inch sonsor (according to a survey by Fulfim