Question

Gainesboro Machine Tools Corporation answer the following questions: What changes have developed and what are their consequences ? How has this improved or hurt the

Gainesboro Machine Tools Corporation answer the following questions:

What changes have developed and what are their consequences?

How has this improved or hurt the companys financial situation?

What marketplace conditions prompted the changes?

Have those conditions improved? Explain.

Gainesboro Machine Tools Corporation

In mid-September 2005, Ashley Swenson, chief financial officer (CFO) of Gainesboro Machine Tools Corporation, paced the floor of her Minnesota office. She needed to submit a recommendation to Gainesboros board of directors regarding the companys dividend policy, which had been the subject of an ongoing debate among the firms senior managers. Compounding her problem was the uncertainty surrounding the recent impact of Hurricane Katrina, which had caused untold destruction across the southeastern United States. In the weeks after the storm, the stock market had spiraled downward and, along with it, Gainesboros stock, which had fallen 18%, to $22.15. In response to the market shock, a spate of companies had announced plans to buy back stock. While some were motivated by a desire to signal confidence in their companies as well as in the U.S. financial markets, still others had opportunistic reasons. Now, Ashley Swensons dividend-decision problem was compounded by the dilemma of whether to use company funds to pay shareholder dividends or to buy back stock.

Background on the Dividend Question

After years of traditionally strong earnings and predictable dividend growth, Gainesboro had faltered in the past five years. In response, management implemented two extensive restructuring programs, both of which were accompanied by net losses. For three years in a row since 2000, dividends had exceeded earnings. Then, in 2003, dividends were decreased to a level below earnings. Despite extraordinary losses in 2004, the board of directors declared a small dividend. For the first two quarters of 2005, the board declared no dividend. But in a special letter to shareholders, the board committed itself to resuming payment of the dividend as soon as possibleideally, sometime in 2005.

In a related matter, senior management considered embarking on a campaign of corporate-image advertising, together with changing the name of the corporation to Gainesboro Advanced Systems International, Inc. Management believed that the name change would help improve the investment communitys perception of the company.

Overall, managements view was that Gainesboro was a resurgent company that demonstrated great potential for growth and profitability. The restructurings had revitalized the companys operating divisions. In addition, the newly developed machine tools designed on state-of-the-art computers showed signs of being well received in the market, and promised to render the competitors products obsolete. Many within the company viewed 2005 as the dawning of a new era, which, in spite of the companys recent performance, would turn Gainesboro into a growth stock. The company had no Moodys or Standard & Poors rating because it had no bonds out- standing, but Value Line rated it an A company.1

Out of this combination of a troubled past and a bright future arose Swensons dilemma. Did the market view Gainesboro as a company on the wane, a blue-chip stock, or a potential growth stock? How, if at all, could Gainesboro affect that perception? Would a change of name help to positively frame investors views of the firm? Did the companys investors expect capital growth or steady dividends? Would a stock buyback instead of a dividend affect investors perceptions of Gainesboro in any way? And, if those questions could be answered, what were the implications for Gainesboros future dividend policy?

The Company

Gainesboro Corporation was founded in 1923 in Concord, New Hampshire, by two mechanical engineers, James Gaines and David Scarboro. The two men had gone to school together and were disenchanted with their prospects as mechanics at a farm- equipment manufacturer.

In its early years, Gainesboro had designed and manufactured a number of machinery parts, including metal presses, dies, and molds. In the 1940s, the companys large manufacturing plant produced armored-vehicle and tank parts and miscellaneous equipment for the war effort, including riveters and welders. After the war, the company concentrated on the production of industrial presses and molds, for plastics as well as metals. By 1975, the company had developed a reputation as an innovative producer of industrial machinery and machine tools.

In the early 1980s, Gainesboro entered the new field of computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM). Working with a small software company, it developed a line of presses that could manufacture metal parts by responding to computer commands. Gainesboro merged the software company into its operations and, over the next several years, perfected the CAM equipment. At the same time, it developed a superior line of CAD software and equipment that would allow an engineer to design a part to exacting specifications on a computer. The design could then be entered into the companys CAM equipment, and the parts could be manufactured without the use of blueprints or human interference. By the end of 2004, CAD/CAM equipment and software were responsible for about 45% of sales; presses, dies, and molds made up 40% of sales; and miscellaneous machine tools were 15% of sales.

Most press and mold companies were small local or regional firms with limited clientele. For that reason, Gainesboro stood out as a true industry leader. Within the CAD/CAM industry, however, a number of larger firms, including Autodesk, Inc., Cadence Design, and Synopsys, Inc., competed for dominance of the growing market.

Throughout the 1990s, Gainesboro helped set the standard for CAD/CAM, but the aggressive entry of large foreign firms into CAD/CAM and the rise of the U.S. dollar dampened sales. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, technological advances and aggressive venture capitalism fueled the entry of highly specialized, state-of-the-art CAD/CAM firms. Gainesboro fell behind some of its competition in the development of user-friendly software and the integration of design and manufacturing. As a result, revenues slipped from a high of $911 million, in 1998, to $757 million, in 2004.

To combat the decline in revenues and to improve weak profit margins, Gainesboro took a two-pronged approach. First, it devoted a greater share of its research-and- development budget to CAD/CAM in an effort to reestablish its leadership in the field. Second, the company underwent two massive restructurings. In 2002, it sold two unprofitable lines of business with revenues of $51 million, sold two plants, eliminated five leased facilities, and reduced personnel. Restructuring costs totaled $65 million. Then, in 2004, the company began a second round of restructuring by altering its manufacturing strategy, refocusing its sales and marketing approach, and adopting administrative procedures that allowed for a further reduction in staff and facilities. The total cost of the operational restructuring in 2004 was $89 million.

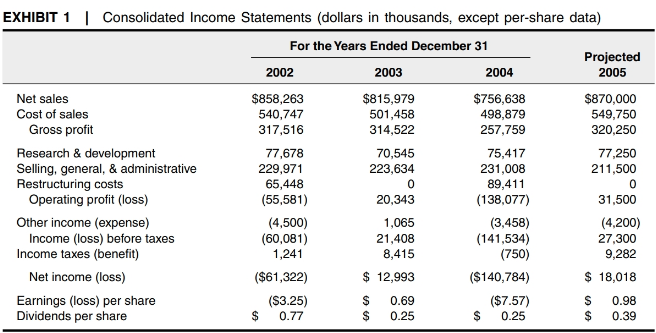

The companys recent consolidated income statements and balance sheets are provided in Exhibits 1 and 2. Although the two restructurings produced losses totaling $202 million in 2002 and 2004, by 2005 the restructurings and the increased emphasis on CAD/CAM research appeared to have launched a turnaround. Not only was the company leaner, but also the research led to the development of a system that Gainesboros management believed would redefine the industry. Known as the Artificial Workforce, the system was an array of advanced control hardware, software, and applications that could distribute information throughout a plant.

Essentially, the Artificial Workforce allowed an engineer to design a part on CAD software and input the data into CAM equipment that could control the mixing of chemicals or the molding of parts from any number of different materials on different machines. The system could also assemble and can, box, or shrink-wrap the finished product. The Artificial Workforce ran on complex circuitry and highly advanced software that allowed the machines to communicate with each other electronically. Thus, a product could be designed, manufactured, and packaged solely by computer no matter how intricate it was.

Gainesboro had developed applications of the product for the chemicals industry and for the oil- and gas-refining industries in 2004 and, by the next year, it had created applications for the trucking, automobile-parts, and airline industries.

By October 2004, when the first Artificial Workforce was shipped, Gainesboro had orders totaling $75 million. By year end, the backlog was $100 million. The future for the product looked bright. Several securities analysts were optimistic about the products impact on the company. The following comments paraphrase their thoughts:

The Artificial Workforce products have compelling advantages over competing entries, which will enable Gainesboro to increase its share of a market that, ignoring periodic growth spurts, will expand at a real annual rate of about 5% over the next several years. The company is producing the Artificial Workforce in a new automated facility, which, when in full swing, will help restore margins to levels not seen in years. The important question now is how quickly Gainesboro will be able to ship in volume. Manufacturing mishaps and missing components delayed production growth through May 2005, putting it about six months beyond the original target date. And start-up costs, which were a significant factor in last years deficits, have continued to penalize earnings. Our estimates assume that production will proceed smoothly from now on and that it will approach the optimum level by years end.

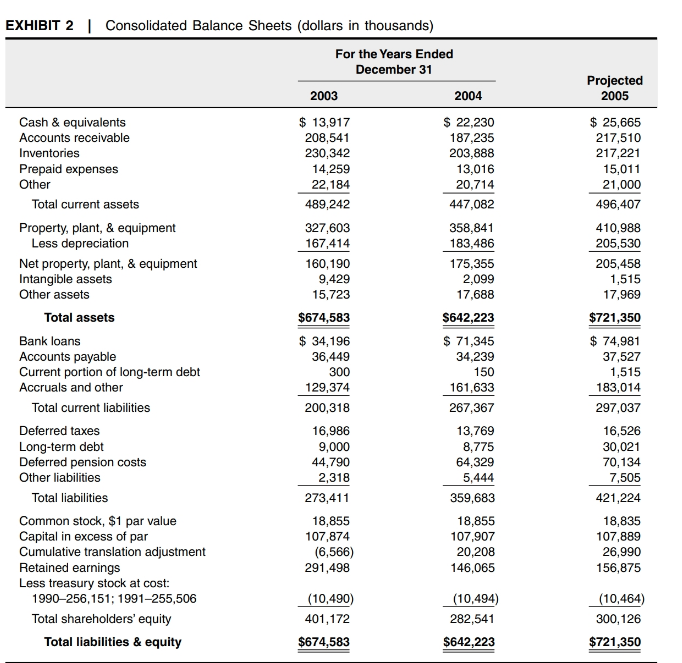

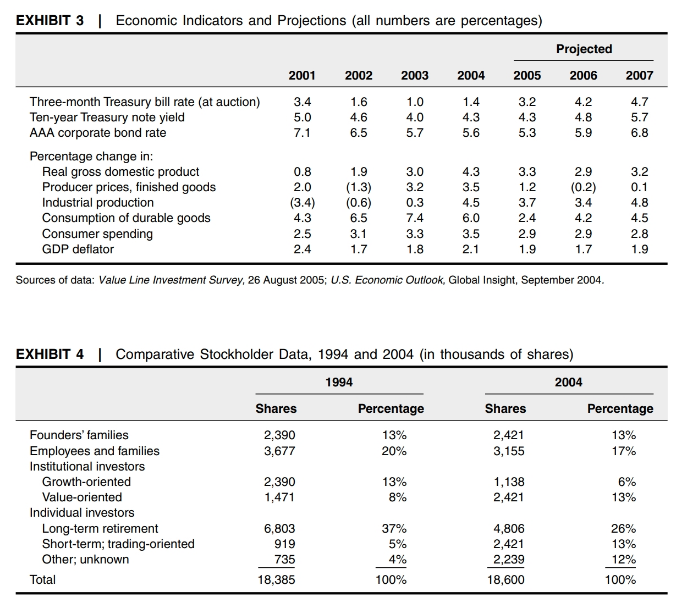

Gainesboros management expected domestic revenues from the Artificial Workforce series to total $90 million in 2005 and $150 million in 2006. Thereafter, growth in sales would depend on the development of more system applications and the creation of system improvements and add-on features. International sales through Gainesboros existing offices in Frankfurt, Germany; London, England; Milan, Italy; and Paris, France; and new offices in Hong Kong, China; Seoul, Korea; Manila, Philippines; and Tokyo, Japan, were expected to provide additional revenues of $150 million by as early as 2007. Currently, international sales accounted for approximately 15% of total corporate revenues. Two factors that could affect sales were of some concern to Gainesboro. First, although the company had successfully patented several of the processes used by the Artificial Workforce system, management had received hints through industry observers that two strong competitors were developing comparable products and would probably introduce them within the next 12 months. Second, sales of molds, presses, machine tools, and CAD/CAM equipment and software were highly cyclical, and current pre- dictions about the strength of the U.S. economy were not encouraging. As shown in Exhibit 3, real GDP (gross domestic product) growth was expected to hover at a steady but unimpressive 3.0% over the next few years. Industrial production, which had improved significantly since 2001, would likely indicate a trend slightly downward next year and the year after that. Despite the macroeconomic environment, Gainesboros management remained optimistic about the companys prospects because of the successful introduction of the Artificial Workforce series.

Corporate Goals

A number of corporate objectives had grown out of the restructurings and recent technological advances. First and foremost, management wanted and expected the firm to grow at an average annual compound rate of 15%. A great deal of corporate planning had been devoted to that goal over the past three years and, indeed, second-quarter financial data suggested that Gainesboro would achieve revenues of about $870 million in 2005, as shown in Exhibit 1. If Gainesboro achieved a 15% compound rate of growth through 2011, the company could reach $2.0 billion in sales and $160 million in net income.

In order to achieve that growth goal, Gainesboro management proposed a strategy relying on three key points. First, the mix of production would shift substantially. CAD/CAM and peripheral products on the cutting edge of industrial technology would account for three-quarters of sales, while the companys traditional presses and molds would account for the remainder. Second, the company would expand aggressively in the international arena, whence it hoped to obtain half of its sales and profits by 2011. This expansion would be achieved through opening new field sales offices around the world. Third, the company would expand through joint ventures and acquisitions of small software companies, which would provide half of the new products through 2011; in-house research would provide the other half.

The company had had an aversion to debt since its inception. Management believed that small amounts of debt, primarily to meet working-capital needs, had their place, but that anything beyond a 40% debt-to-equity ratio was, in the oft-quoted words of Gainesboro cofounder David Scarboro, unthinkable, indicative of sloppy management, and flirting with trouble. Senior management was aware that equity was typically more costly than debt, but took great satisfaction in the companys doing it on its own. Gainesboros highest debt-to-capital ratio in the past 25 years (22%) had occurred in 2004, and was still the subject of conversations among senior managers.

Although eleven members of the Gaines and the Scarboro families owned 13% of the companys stock and three were on the board of directors, management placed the interests of the outside shareholders first. (Shareholder data are provided in Exhibit 4.) Stephen Gaines, board chair and grandson of the cofounder, sought to maximize growth in the market value of the companys stock over time.

At 61, Gaines was actively involved in all aspects of the companys growth. He dealt fluently with a range of technical details of Gainesboros products, and was especially interested in finding ways to improve the companys domestic market share. His retirement was no more than four years away, and he wanted to leave a legacy of corporate financial strength and technological achievement. The Artificial Work- force, a project that he had taken under his wing four years earlier, was finally beginning to bear fruit. Gaines now wanted to ensure that the firm would also soon be able to pay a dividend to its shareholders.

Gaines took particular pride in selecting and developing promising young managers. Ashley Swenson had a bachelors degree in electrical engineering and had been a systems analyst for Motorola before attending graduate school. She had been hired in 1995, fresh out of a well-known MBA program. By 2004, she had risen to the position of CFO.

Dividend Policy

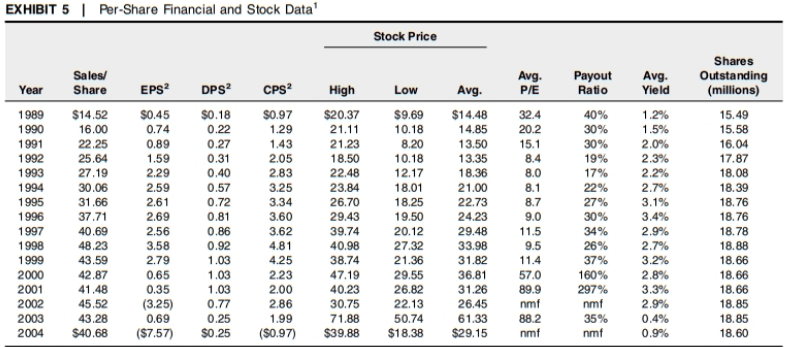

Gainesboros dividend and stock-price histories are presented in Exhibit 5. Before 1999, both earnings and dividends per share had grown at a relatively steady pace, but Gainesboros troubles in the early 2000s had taken their toll on earnings. Consequently, dividends were pared back in 2003 to $0.25 a sharethe lowest dividend since 1990. In 2004, the board of directors declared a payout of $0.25 a share, despite reporting the largest per-share earnings loss in the firms history and despite, in effect, having to borrow to pay that dividend. In the first two quarters of 2005, the directors did not declare a dividend. In a special letter to shareholders, however, the directors declared their intention to continue the annual payout later in 2005.

In August 2005, Swenson contemplated her choices from among the three possible dividend policies to decide which one she should recommend:

Zero-dividend payout: This option could be justified in light of the firms strategic emphasis on advanced technologies and CAD/CAM, and reflected the huge cash requirements of such a move. The proponents of this policy argued that it would signal that the firm now belonged in a class of high-growth and high-technology firms. Some securities analysts wondered whether the market still considered Gainesboro a traditional electrical-equipment manufacturer or a more technologically advanced CAD/CAM company. The latter category would imply that the market expected strong capital appreciation, but perhaps little in the way of dividends. Others cited Gainesboros recent performance problems. One questioned the wisdom of ignoring the financial statements in favor of acting like a blue chip. Was a high dividend in the long-term interests of the company and its stockholders, or would the strategy backfire and make investors skittish?

Swenson recalled a recently published study that found that firms were dis- playing a lower propensity to pay dividends. The study found that the percentage of firms paying cash dividends had dropped from 66.5%, in 1978, to 20.8%, in 1999.2 In that light, perhaps the market would react favorably, if Gainesboro adopted a zero dividend-payout policy.

40% dividend payout or a dividend of around $0.20 a share: This option would restore the firm to an implied annual dividend payment of $0.80 a share, the highest since 2001. Proponents of this policy argued that such an announcement was justified by expected increases in orders and sales. Gainesboros investment banker suggested that the market might reward a strong dividend that would bring the firms payout back in line with the 36% average within the electrical- industrial-equipment industry and with the 26% average in the machine-tool industry. Still others believed that it was important to send a strong signal to shareholders, and that a large dividend (on the order of a 40% payout) would suggest that the company had conquered its problems and that its directors were confident of its future earnings. Supporters of this view argued that borrowing to pay dividends was consistent with the behavior of most firms. Finally, some older managers opined that a growth rate in the range of 10% to 20% should accompany a dividend payout of between 30% and 50%.

Residual-dividend payout: A few members of the finance department argued that Gainesboro should pay dividends only after it had funded all the projects that offered positive net present values (NPV). Their view was that investors paid man- agers to deploy their funds at returns better than they could otherwise achieve, and that, by definition, such investments would yield positive NPVs. By deploying funds into those projects and returning otherwise unused funds to investors in the form of dividends, the firm would build trust with investors and be rewarded through higher valuation multiples.

Another argument in support of that view was that the particular dividend policy was irrelevant in a growing firm: any dividend paid today would be offset by dilution at some future date by the issuance of shares needed to make up for the dividend. This argument reflected the theory of dividends in a perfect market advanced by two finance professors, Merton Miller and Franco Modigliani.3 To Ashley Swenson, the main disadvantage of this policy was that dividend payments would be unpredictable. In some years, dividends could even be cut to zero, possibly imposing negative pressure on the firms share price. Swenson was all too aware of Gainesboros own share-price collapse following its dividend cut. She recalled a study by another finance professor, John Lintner,4 which found that firms dividend payments tended to be sticky upwardthat is, dividends would rise over time and rarely fall, and that mature, slower-growth firms paid higher dividends, while high-growth firms paid lower dividends.

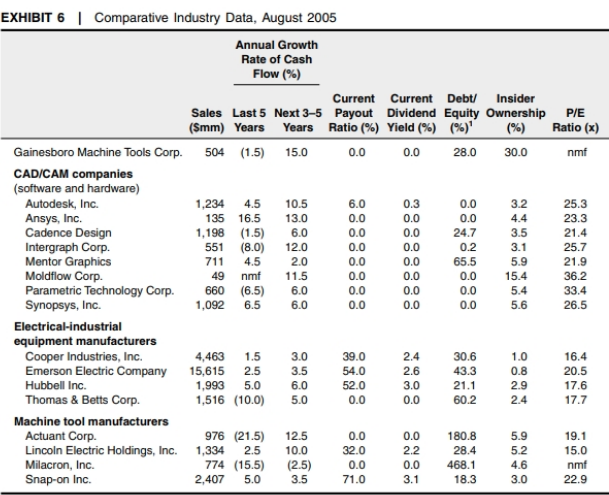

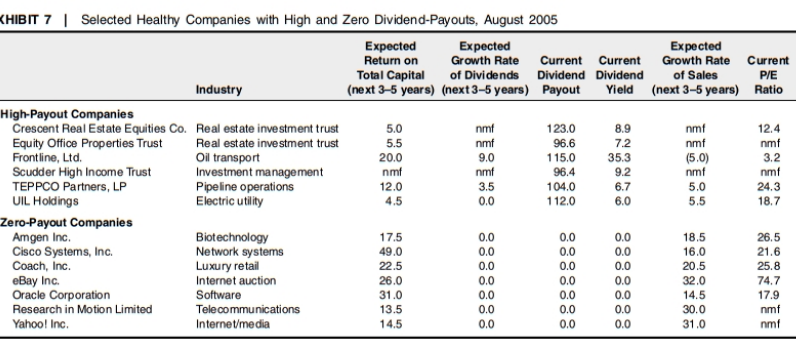

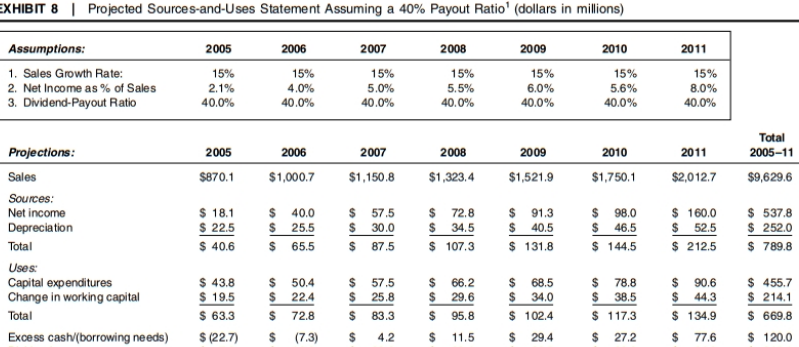

In response to the internal debate, Swensons staff pulled together Exhibits 6 and 7, which present comparative information on companies in three industries CAD/CAM, machine tools, and electrical-industrial equipmentand a sample of high- and low-payout companies. To test the feasibility of a 40% dividend-payout rate, Swenson developed the projected sources-and-uses of cash statement provided in Exhibit 8. She took the boldest approach by assuming that the company would grow at a 15% compound rate, that margins would improve over the next few years to historical levels, and that the firm would pay a dividend of 40% of earnings every year. In particular, the forecast assumed that the firms net margin would hover between 4% and 6% over the next six years, and then increase to 8% in 2011. The firms operating executives believed that this increase in profitability was consistent with economies of scale to be achieved upon the attainment of higher operating output through the Artificial Workforce series.

Image Advertising and Name Change

As part of a general review of the firms standing in the financial markets, Gainesboros director of Investor Relations, Cathy Williams, had concluded that investors misperceived the firms prospects and that the firms current name was more consistent with its historical product mix and markets than with those projected for the future. Williams commissioned surveys of readers of financial magazines, which revealed a relatively low awareness of Gainesboro and its business. Surveys of stockbrokers revealed a higher awareness of the firm, but a low or mediocre outlook on Gainesboros likely returns to shareholders and its growth prospects. Williams retained a consulting firm that recommended a program of corporate-image advertising targeted toward guiding the opinions of institutional and individual investors. The objective was to enhance the firms visibility and image. Through focus groups, the image consultants identified a new name that appeared to suggest the firms promising new strategy: Gainesboro Advanced Systems International, Inc. Williams estimated that the image- advertising campaign and name change would cost approximately $10 million.

Stephen Gaines was mildly skeptical. He said, Do you mean to raise our stock price by marketing our shares? This is a novel approach. Can you sell claims on a company the way Procter & Gamble markets soap? The consultants could give no empirical evidence that stock prices responded positively to corporate-image campaigns or name changes, though they did offer some favorable anecdotes.

Conclusion

Swenson was in a difficult position. Board members and management disagreed on the very nature of Gainesboros future. Some managers saw the company as entering a new stage of rapid growth and thought that a large (or, in the minds of some, any) dividend would be inappropriate. Others thought that it was important to make a strong public gesture showing that management believed that Gainesboro had turned the corner and was about to return to the levels of growth and profitability seen in the 1980s and 90s. This action could only be accomplished through a dividend. Then there was the confounding question about the stock buyback. Should Gainesboro use its funds to repurchase stocks instead of paying out a dividend? As Swenson wrestled with the different points of view, she wondered whether Gainesboros management might be representative of the companys shareholders. Did the majority of public shareholders own stock for the same reason, or were their reasons just as diverse as those of management?

EXHIBIT Consolidated Income Statements (dollars in thousands, except per-share data) For the Years Ended December 31 Projected 2002 2003 2004 2005 $858,263 540,747 317,516 77,678 229,971 65,448 (55,581) (4,500) (60,081) 1,241 ($61,322) Net sales Cost of sales $815,979 501,458 314,522 70,545 223,634 $756,638 498,879 257,759 $870,000 549,750 320,250 Gross profit 75,417 231,008 89,411 (138,077) (3,458) (141,534) (750) ($140,784) Research & development Selling, general, & administrative Restructuring costs 77,250 211,500 20,343 31,500 Operating profit (loss) Other income (expense) (4,200) 27,300 9,282 1,065 21,408 Income (loss) before taxes Income taxes (benefit) 8,415 $ 12,993 18,018 S 0.98 $ 0.39 Net income (loss) Earnings (loss) per share Dividends per share (S3.25) $ 0.77 $ 0.69 $ 0.25 ($7.57) $ 0.25 EXHIBIT Consolidated Income Statements (dollars in thousands, except per-share data) For the Years Ended December 31 Projected 2002 2003 2004 2005 $858,263 540,747 317,516 77,678 229,971 65,448 (55,581) (4,500) (60,081) 1,241 ($61,322) Net sales Cost of sales $815,979 501,458 314,522 70,545 223,634 $756,638 498,879 257,759 $870,000 549,750 320,250 Gross profit 75,417 231,008 89,411 (138,077) (3,458) (141,534) (750) ($140,784) Research & development Selling, general, & administrative Restructuring costs 77,250 211,500 20,343 31,500 Operating profit (loss) Other income (expense) (4,200) 27,300 9,282 1,065 21,408 Income (loss) before taxes Income taxes (benefit) 8,415 $ 12,993 18,018 S 0.98 $ 0.39 Net income (loss) Earnings (loss) per share Dividends per share (S3.25) $ 0.77 $ 0.69 $ 0.25 ($7.57) $ 0.25

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started