GUARANTEED LIKE

THIS SHOULD BE BETTER

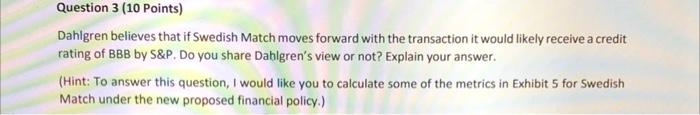

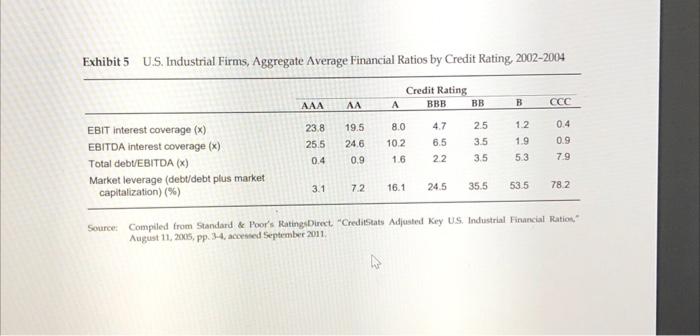

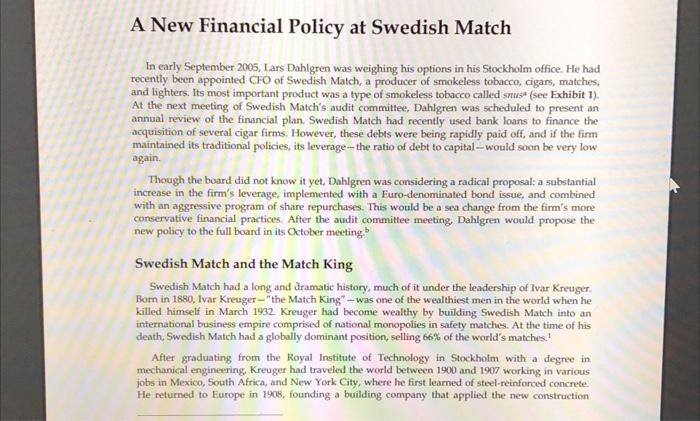

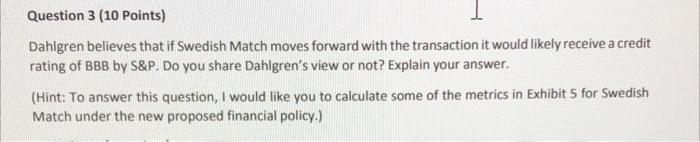

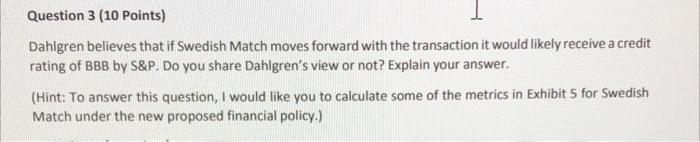

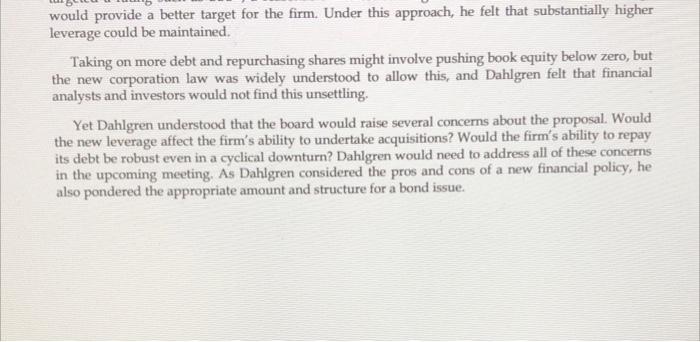

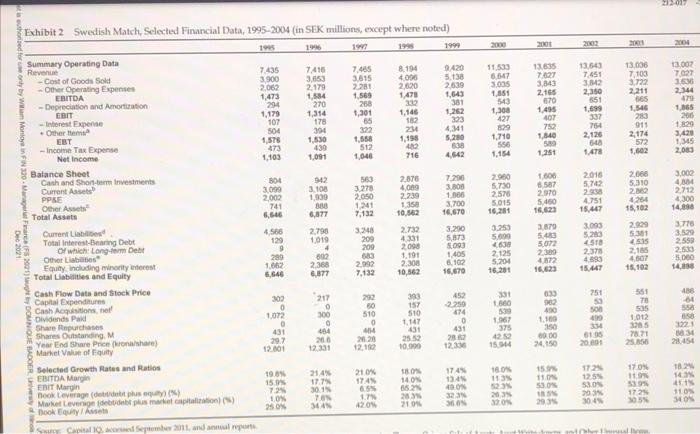

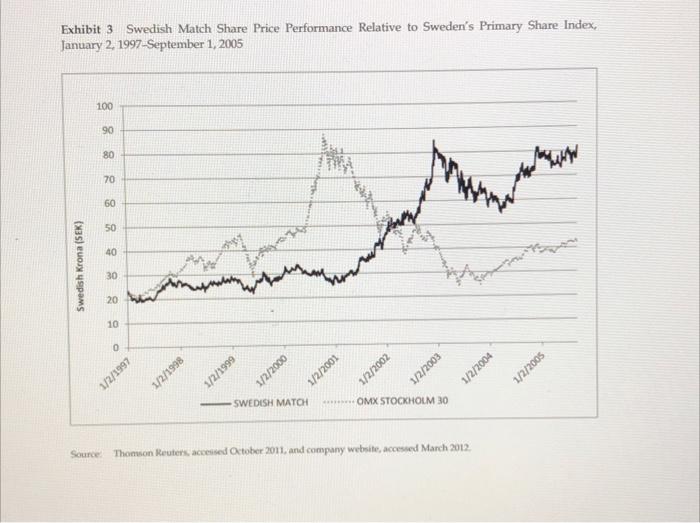

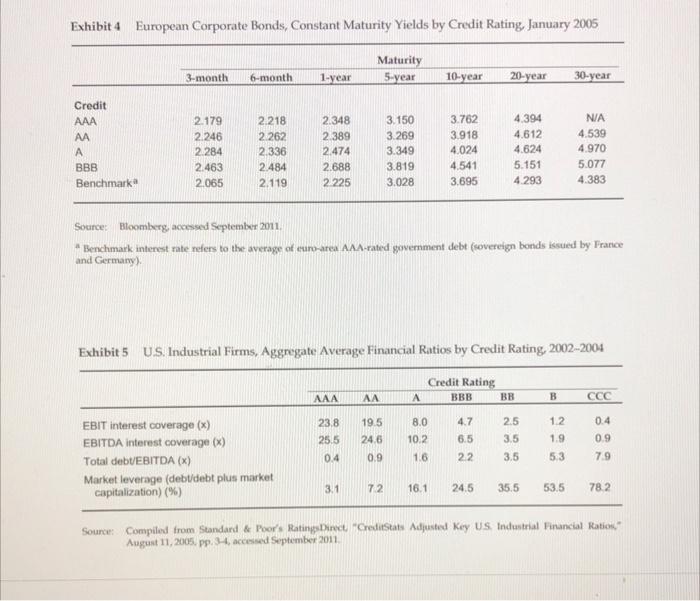

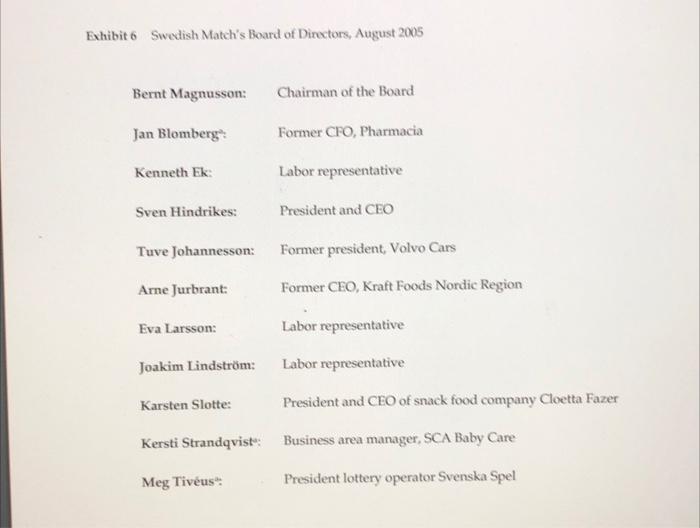

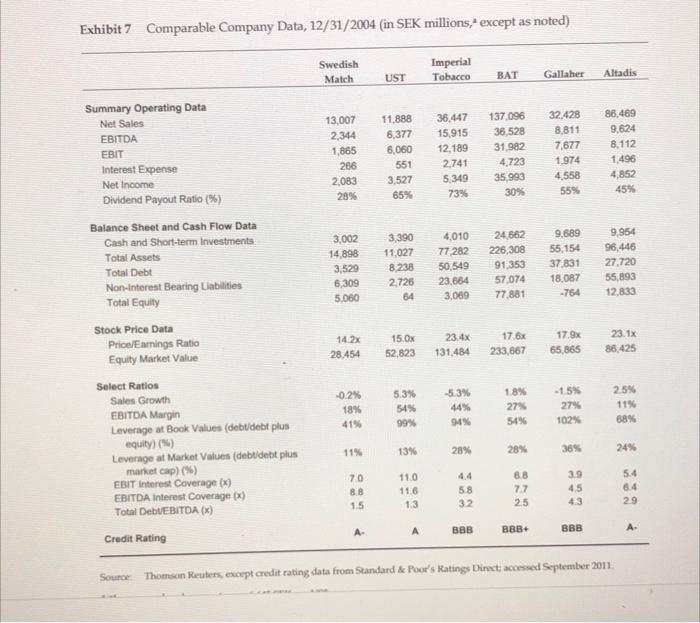

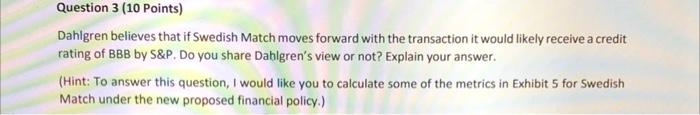

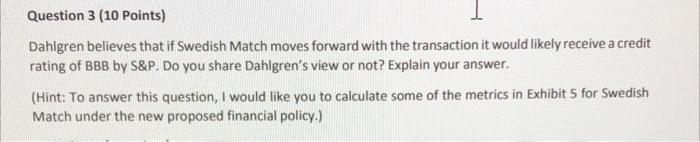

Question 3 (10 Points) Dahlgren believes that if Swedish Match moves forward with the transaction it would likely receive a credit rating of BBB by S&P. Do you share Dahlgren's view or not? Explain your answer. (Hint: To answer this question, I would like you to calculate some of the metrics in Exhibit 5 for Swedish Match under the new proposed financial policy.) Exhibit 5 U.S. Industrial Firms, Aggregate Average Financial Ratios by Credit Rating, 2002-2004 Credit Rating BBB BB AAA AA A B 238 1.2 19.5 24.6 0.9 25.5 0.4 EBIT interest coverage (x) EBITDA interest coverage (*) Total debUEBITDA (X) Market leverage (debt/debt plus market capitalization) (%) 8.0 10.2 1.6 4.7 6.5 22 1.9 25 3.5 3.5 0.4 0.9 7.9 5.3 3.1 7.2 16.1 24.5 35.5 53.5 782 Source: Compiled from Standard & Poor's Rating Direct "CreditStats Adjusted Key US. Industrial Financial Ration" August 11, 2005, pp. 3-4 accessed September 2011 A New Financial Policy at Swedish Match In early September 2005, Lars Dahlgren was weighing his options in his Stockholm office. He had recently been appointed CFO of Swedish Match, a producer of smokeless tobacco, cigars, matches, and lighters. Its most important product was a type of smokeless tobacco called smus* (see Exhibit 1). At the next meeting of Swedish Match's audit committee, Dahlgren was scheduled to present an annual review of the financial plan. Swedish Match had recently used bank loans to finance the acquisition of several cigar firms. However, these debts were being rapidly paid off, and if the firm maintained its traditional policies, its leverage--the ratio of debt to capital --would soon be very low again. Though the board did not know it yet, Dahlgren was considering a radical proposals a substantial increase in the firm's leverage, implemented with a Furo-denominated bond issue, and combined with an aggressive program of share repurchases. This would be a sea change from the firm's more conservative financial practices. After the audit committee meeting, Dahlgren would propose the new policy to the full board in its October meeting Swedish Match and the Match King Swedish Match had a long and dramatic history, much of it under the leadership of Ivar Kreuger, Bom in 1880, Ivar Kreuger - "the Match King" - was one of the wealthiest men in the world when he killed himself in March 1932. Kreuger had become wealthy by building Swedish Match into an international business empire comprised of national monopolies in safety matches. At the time of his death, Swedish Match had a globally dominant position, selling 66% of the world's matches! After graduating from the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm with a degree in mechanical engineering, Kreuger had traveled the world between 1900 and 1907 working in various jobs in Mexico, South Africa, and New York City, where he first learned of steel-reinforced concrete He returned to Europe in 1908, founding a building company that applied the new construction the Swedish Match name. The firm's owner spun off Swedish Match in an IPO in 1996. At that time, the business consisted of matches and lighters, cigarettes, and niche tobacco products (cigars, pipe tobacco, and smokeless tobacco). In 1999, the company divested its remaining cigarette operations to concentrate on niche tobacco products. The firm made acquisitions in cigars, notably of General Cigars, headquartered in Virginia, in 1999. The divestment of cigarettes was a strategic move. In the Swedish market more and more people felt there were advantages to snus, a more socially accepted tobacco product, and Swedish Match was uniquely positioned to take advantage of this growth (Exhibit 2 shows summary financial data for the decade ending in 2004.) Swedish Match in 2005 By 2005, Swedish Match was a worldwide leader in smokeless tobacco products including snuff. snus, and chewing tobacco. The tobacco was sourced from carefully selected suppliers and manufactured in Sweden. These business segments accounted for 32% of 2004 sales and 72% of operating income. These products were most popular in Scandinavia and the United States Snus had been banned in the EU since 1992, but it remained legal in Sweden. Its sale was also allowed in Norway, which remained outside the EU. The EU debated the regulatory status of snus, and a general trend emerged of increased tobacco restrictions as well as concern about possible future regulatory restrictions. However, some analysts argued that snus faced lower regulatory risks than cigarettes because the health risks were different In Sweden and Norway, about one million people used snus in 2004, and Swedish Match controlled 96% of the market in Scandinavia, popular snus brands such as General, Goteborgs Rape Ettan, and Catch held a dominant market position, Sweden was unique in the EU with its low prevalence of cigarette smoking Among Swedish men, the use of snus was more common than smoking cigarettes Growth was also stimulated by the fact that the EU decided to remove the cancer warning from the snus can in 2002. With attractive margins and strong growth prospects, several competitors surfaced during this time on the Swedish market The United States was the biggest growth market for smokeless tobacco products, with over 900 million cans of snuff and snus sold in the US in 2004. In the United States, Swedish Match offered moist snuff brands Longhom and Timberwolf and the snus brand General. The primary brands competing in the US market included Grizzly. Hawken, and Kodiak, all produced by American Snuff Company, and Red Seal, Copenhagen, Rooster, and Skoal, produced by US, Smokeless In addition to snus, snuff, chewing tobacco, and cigars, Swedish Match also produced pipe tobacco, although this was a declining market (it shrunk 14% in US, sales volume in 2004, for example). Pipe tobacco accounted for about 9% of the company's operating income. Swedish Match maintained a 16% market share in the US and profitability for pipe tobacco remained strong." Finally, matches accounted for just 11% of the company's sales in 2004 and 1% of operating income. Overall, Scandinavia, the US and the rest of the world each represented approximately one-third of company sales. Costs matched revenues fairly well, so the net currency exposure of Swedish Match was low Swedish Match had a conservative policy in all financial matters. At the time of the firm's IPO in 1996, management had decided to target book equity of at least 30% of assets (corresponding to interest-bearing debt over assets of 20%-40%, depending on the amount of non-interest-bearing liabilities). The firm paid high dividends and made some share repurchases. For a period, leverage had increased due to acquisitions in the cigar area. The company had an international short-term bond program (the "Global Medium Term Note Program") and a small Swedish bond program, both started in the late 1990s and by then largely paid off. The firm had a credit rating of A- from rating agency S&P" (see Exhibit 5 for data on ratings) A New Financial Policy Swedish Match's financial policy was set by the board of directors (see Exhibit 6 for a list of members). In accordance with Swedish law, two labor representatives were voting members on the board. Swedish Match's president and CEO, Sven Hindrikes, appointed in 2004, was also a member of the board. Hindrikes had asked Dahlgren to propose a detailed financial policy first to the board's audit committee and then to the full board in its October 25 meeting. The board would decide on a financial policy, including how to measure leverage and what targets to apply. Several factors played into Dahlgren's sense that this was a good time to reconsider the company's financial policies. First, Sweden had recently instituted a new corporation law that allowed firms to repurchase shares even if it resulted in negative consolidated book equity for the group. Second, a continuation of the current policy would reduce leverage in the next few years. In Dahlgren's view, Swedish Match faced several potential benefits of taking on more debt. Leverage reduced the corporate income tax bill. As in the United States and many other countries, interest expenses were deductible from corporate income under Swedish tax law. The corporate income tax rate was 28% also expose the firm to bond market conditions when needing to refinance. Additionally, taking on more debt would reduce financial flexibility going forward. Dahlgren also had to consider the risk to the firm's business. If the smokeless tobacco products faced more competition, the ability to pay interest payments or principal could be in doubt. A forced sale of assets, or even bankruptcy, was a possibility. Credit rating agencies would lower Swedish Match's credit rating accordingly. Dahlgren and finance vice president Joakim Tilly discussed a bond issue in the European market, given the modest size of the Swedish bond market. Based on conversations with bankers in London, they felt that bond issues below 300 million, or approximately SEK 3 billion, would be impractical and expensive to issue. Such a bond would have interest and principal repayments in euros, but it would be fairly easy to swap those payments with a bank so that Swedish Match could pay interest in SEK. The effective interest rate after swapping was expected to be similar to euro rates. Analysts expected EBITDA to be around SEK 3 billion per year in the next few years. Given this, Dahlgren and Tilly thought that a BBB+ rating would be sustainable under as much as SEK 4 billion of additional debt. Swedish Match's board wanted to be conservative, and thought that it was important to be prepared for a worst-case scenario where profitability dropped by as much as half. Dahlgren and Tilly thus felt it was prudent to consider a temporary drop in EBITDA to as low as SEK 15 billion Swedish Match shares were currently trading at SEK 80 in Stockholm, slightly up over the year to date. Decision Dahlgren and Tilly believed that sensitivity analyses, theoretical valuation impacts, signaling considerations, and the availability of financing should be key inputs into the decision. Dahlgren elaborated: "Financial risk can ultimately be defined as the risk for a company of either failing to pay the interest on its loans or failing to pay back the entire principal at maturity... traditional solvency ratios such as equity over total assets poorly reflect these risks." Instead, he felt that a policy that targeted a rating such as BBB+, a reasonable interest coverage ratio, and suitable market leverage would provide a better target for the firm. Under this approach, he felt that substantially higher leverage could be maintained. Taking on more debt and repurchasing shares might involve pushing book equity below zero, but the new corporation law was widely understood to allow this, and Dahlgren felt that financial analysts and investors would not find this unsettling Yet Dahlgren understood that the board would raise several concerns about the proposal. Would a considerations, and the availability of financing should be key inputs into the decision. Dahlgren elaborated: "Financial risk can ultimately be defined as the risk for a company of either failing to pay the interest on its loans or failing to pay back the entire principal at maturity traditional solvency ratios such as equity over total assets poorly reflect these risks." Instead, he felt that a policy that targeted a rating such as BBB+, a reasonable interest coverage ratio, and suitable market leverage would provide a better target for the firm. Under this approach, he felt that substantially higher leverage could be maintained. Taking on more debt and repurchasing shares might involve pushing book equity below zero, but the new corporation law was widely understood to allow this, and Dahlgren felt that financial analysts and investors would not find this unsettling Yet Dahlgren understood that the board would raise several concerns about the proposal. Would the new leverage affect the firm's ability to undertake acquisitions? Would the firm's ability to repay its debt be robust even in a cyclical downturn? Dahlgren would need to address all of these concerns in the upcoming meeting. As Dahlgren considered the pros and cons of a new financial policy, he also pondered the appropriate amount and structure for a bond issue Learning Objectives & Instructions In this assignment you will analyze the proposed change in the financial policy of Swedish Match. The case is set around September 2005. During this time period Lars Dahlgren, the CFO of Swedish Match, is considering a radical change in the firm's financial policy. Specifically, Dahlgren is considering whether to increase the leverage of the firm through a bond issuance, and using the money raised from the bond issuance to repurchase shares. As part of this assignment you will analyze whether this transaction will ultimately be to the benefit of Swedish Match's shareholders. Additionally, this assignment asks you to discuss the benefits and costs associated with debt financing. This case study is slightly more qualitative in nature compare to the last one. Therefore, it is especially important that you read the entire case study in the course packet carefully before attempting to answer the questions below. You might have to read the case study several times to make sure you have all the information that you need. All of the information you require to solve this assignment is in the course packet (see syllabus) You may work on this case study independently or in groups of up to four students. If you work in groups, please only hand in one copy of your write-up per group and make sure to list the full names of all your group members. You will hand in a type written copy of your write-up at the beginning of class on the due date. The first page should have the title "FIN 320 - Swedish Match Case" and list your full namels). I will not accept late submissions or hand written submissions, or submissions by email Please follow the following additional instructions when completing the assignment Assume a corporate tax rate of 28% for Swedish Match Assume that Swedish Match has no excess cash Assume that if Swedish Match completes the transaction it will issue a perpetual bond with a face value of SEK 4 billion Assume that the yield on a perpetual bond equals the yield on a 30 year bond Question 3 (10 Points) Dahlgren believes that if Swedish Match moves forward with the transaction it would likely receive a credit rating of BBB by S&P. Do you share Dahlgren's view or not? Explain your answer. (Hint: To answer this question, I would like you to calculate some of the metrics in Exhibit 5 for Swedish Match under the new proposed financial policy.) A New Financial Policy at Swedish Match In early September 2005, Lars Dahlgren was weighing his options in his Stockholm office. He had recently been appointed CFO of Swedish Match, a producer of smokeless tobacco, cigars, matches, and lighters. Its most important product was a type of smokeless tobacco called snus" (see Exhibit 1). At the next meeting of Swedish Match's audit committee, Dahlgren was scheduled to present an annual review of the financial plan. Swedish Match had recently used bank loans to finance the acquisition of several cigar firms. However, these debts were being rapidly paid off, and if the firm maintained its traditional policies, its leverage- the ratio of debt to capital - would soon be very low again Though the board did not know it yet, Dahlgren was considering a radical proposal: a substantial increase in the firm's leverage, implemented with a Euro-denominated bond issue, and combined with an aggressive program of share repurchases. This would be a sea change from the firm's more conservative financial practices . After the audit committee meeting, Dahlgren would propose the new policy to the full board in its October meeting a Swedish Match and the Match King Swedish Match had a long and dramatic history, much of it under the leadership of Ivar Kreuger. Born in 1880, Ivar Kreuger-"the Match King" - was one of the wealthiest men in the world when he killed himself in March 1932. Kreuger had become wealthy by building Swedish Match into an international business empire comprised of national monopolies in safety matches. At the time of his death, Swedish Match had a globally dominant position, selling 66% of the world's matches.! After graduating from the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm with a degree in mechanical engineering, Kreuger had traveled the world between 1900 and 1907 working in various jobs in Mexico, South Africa, and New York City, where he first learned of steel-reinforced concrete. He retumed to Europe in 1908, founding a building company that applied the new construction . technique. The firm, Kreuger & Toll, grew to be worth SEK 1 million by 1911. Matches were the Kreuger family business, however, and Kreuger soon turned his attention there. In 1903, Sweden had 15 match companies. Six of these merged to form Jnkping och Vulcans Tndsticksfabriks AB (J&V). controlling 80% of the Swedish match market and threatening the Kreuger family company. Using contacts in the banking industry and his construction profits, Ivar Kreuger was able to raise debt to finance an expansion of the family's company. He used bank loans to merge Sweden's nine remaining match companies in 1913 into AB Frenade Svenska Tndsticksfabriks (Frenade), with Kreuger in control. During World War 1. J&V sold matches to both sides of the conflict. When the Allies initially Britain, France, and Russia) suspended J&V import licenses, Frenade, which had sold matches only to the Allied side, benefitted. In 1916, J&V was forced to merge with Frenade, forming Swedish Match. Ivar Kreuger had gained complete control over the Swedish market for matches The monopoly in Sweden proved highly profitable, and Kreuger set out to replicate it elsewhere. As a first step, in 1917, Swedish Match acquired majority holdings in Denmark's three match companies, but this tested Kreuger's ability to borrow in Sweden to the limit. To continue expanding Kreuger needed funding beyond the capacity of Swedish banks. In 1923, Kreuger set up the International Match Company (IMCO) in New York City as a way to raise money from American investors Raising equity abroad threatened to put Kreuger in violation of Swedish laws that forbade foreign majority ownership of Swedish companies. To avoid this, Kreuger invented "A" and "B" share classes: B shares gave investors only a small percentage of the voting rights of an A share, allowing investors to buy stock in Kreuger's companies without violating Swedish law. Dual share classes of this type are still in common use around the world. Kreuger also pioneered the use of convertible securities-loans that could be repaid in cash or converted to company stock? By 1925, Swedish Match controlled significant portions of the match industries of Austria. Belgium, Finland, Hungary, Norway, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, and soon thereafter made acquisitions in Japan and the US. Creating national monopolies often required permission from national governments. Beginning in 1925, Kreuger began lending money to governments in exchange for monopoly control of their match markets, Ecuador, France, Germany Greece Hungary, Latvia, Peru, Poland, and Yugoslavia all borrowed money from Kreuger, Swedish Match, IMCO, and the other companies in Kreuger's empire. Kreuger raised ever larger sums in New York. Investors were willing to supply funds for two reasons the high and stable dividends paid to investors, and the national monopolies that sustained these payouts. Kreuger became world famous. The stock market crash in 1929 and the worsening business cycle made things harder for Kreuger, Profitability at Swedish Match faltered as the Great Depression deepened. However, Kreuger's national governments. Beginning in 1925, Kreuger Beyan for monopoly control of their match markets, Ecuador, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Peru, Poland, and Yugoslavia all borrowed money from Kreuger, Swedish Match, IMCO, and the other companies in Kreuger's empire. Kreuger raised ever larger sums in New York. Investors were willing to supply funds for two reasons: the high and stable dividends paid to investors, and the national monopolies that sustained these payouts. Kreuger became world famous. The stock market crash in 1929 and the worsening business cycle made things harder for Kreuger. Profitability at Swedish Match faltered as the Great Depression deepened. However, Kreuger's companies continued paying high dividends to attract new investors. As money ran out, Kreuger paid dividends to his earlier investors with money received from new investors. He covered this up with fraudulent accounting practices and counterfeit documents. This worked for a while, but when Kreuger tried to sell his majority stake in the telecommunications giant Ericsson, an audit by the bankers at J.P. Morgan revealed that some assets were missing. The bank blocked the deal in February 1932, initiating one of the largest financial collapses of all time. All sources of debt funding dried up for Kreuger. The Swedish Match share price collapsed. Within a few weeks, Ivar Kreuger shot himself in a Paris hotel, generating worldwide news.? Swedish Match survived. In the wake of the collapse, the company divested several businesses and focused on matches in Sweden. Over the next 50 years, Swedish Match was owned by a succession of Swedish investors and business groups who operated the match business under various names. By 1992, this match business was combined with the largest Swedish tobacco company, under 2 the Swedish Match name. The firm's owner spun off Swedish Match in an IPO in 1996. At that time, the business consisted of matches and lighters, cigarettes, and niche tobacco products (cigars, pipe tobacco, and smokeless tobacco). In 1999, the company divested its remaining cigarette operations to concentrate on niche tobacco products. The firm made acquisitions in cigars, notably of General Cigars, headquartered in Virginia, in 1999. The divestment of cigarettes was a strategic move. In the Swedish market more and more people felt there were advantages to snus, a more socially accepted tobacco product, and Swedish Match was uniquely positioned to take advantage of this growth. (Exhibit 2 shows summary financial data for the decade ending in 2004.) Swedish Match in 2005 By 2005, Swedish Match was a worldwide leader in smokeless tobacco products including snuff, snus, and chewing tobacco. The tobacco was sourced from carefully selected suppliers and manufactured in Sweden. These business segments accounted for 32% of 2004 sales and 72% of operating income. These products were most popular in Scandinavia and the United States. Snus had been banned in the EU since 1992, but it remained legal in Sweden. Its sale was also allowed in Norway, which remained outside the EU. The EU debated the regulatory status of snus, and a general trend emerged of increased tobacco restrictions as well as concern about possible future regulatory restrictions. However, some analysts argued that snus faced lower regulatory risks than cigarettes because the health risks were different In Sweden and Norway, about one million people used snus in 2004, and Swedish Match controlled 96% of the market. In Scandinavia, popular snus brands such as General, Gteborgs Rap, Ettan, and catch held a dominant market position Sweden was unique in the EU with its low prevalence of cigarette smoking. Among Swedish men, the use of snus was more common than smoking cigarettes. Growth was also stimulated by the fact that the EU decided to remove the cancer warning from the snus can in 2002 With attractive margins and strong growth prospects, several competitors surfaced during this time on the Swedish market The United States was the biggest growth market for smokeless tobacco products, with over 900 million cans of snuff and snus sold in the U.S. in 2004. In the United States, Swedish Match offered moist snuff brands Longhorn and Timberwolf and the snus brand General. The primary brands competing in the US market included Grizzly, Hawken, and Kodiak, all produced by American Snuft Company, and Red Seal, Copenhagen, Rooster, and Skoal, produced by US. Smokeless Tobacco Company. Demand for snus and moist snuff was growing in the US in 2004, as more people chose smokeless tobacco over cigarettes. Red Man, Swedish Match's chewing tobacco brand, was sold only in the United States and was the market leader, with a 43% market share in 2004. and After smokeless tobacco, Swedish Match's most important single product was cigars, which comprised 24% of sales and 59% of operating income in 2004. Swedish Match was the world's number two cigar manufacturer, and the global leader in the premium segment of the U.S. market. 11 Swedish Match produced both machine-made and premium cigars. Premium cigars, which were made by hand, mostly in Latin America and the Caribbean, accounted for 24% of Swedish Match's sales volume, and 20% of operating income in 2004. The market for machine-made cigars in the United States and Western Europe was estimated at about 13 billion cigars per year, of which Swedish Match supplied about 7%. Flavored cigars were considered the segment with the largest growth potential. 12 Chewing tobacco, a stagnating product category sold mostly in the US, generated 8% of sales and 13% of operating income in 2004. In addition to snus, snuff, chewing tobacco, and cigars, Swedish Match also produced pipe tobacco, although this was a declining market (it shrunk 14% in US, sales volume in 2004, for example). Pipe tobacco accounted for about 9% of the company's operating income. Swedish Match maintained a 16% market share in the US, and profitability for pipe tobacco remained strong. 13 Finally, matches accounted for just 11% of the company's sales in 2004 and 1% of operating income. Overall, Scandinavia, the U.S., and the rest of the world each represented approximately one-third of company sales. Costs matched revenues fairly well, so the net currency exposure of Swedish Match was low Swedish Match had a conservative policy in all financial matters. At the time of the firm's IPO in 1996, management had decided to target book equity of at least 30% of assets (corresponding to interest-bearing debt over assets of 20%-40%, depending on the amount of non-interest-bearing liabilities). The firm paid high dividends and made some share repurchases. For a period, leverage had increased due to acquisitions in the cigar area. The company had an international short-term bond program (the "Global Medium Term Note Program") and a small Swedish bond program, both started in the late 1990s and by then largely paid off. The firm had a credit rating of A- from rating agency S&P (see Exhibit 5 for data on ratings) A New Financial Policy Swedish Match's financial policy was set by the board of directors (see Exhibit 6 for a list of members). In accordance with Swedish law, two labor representatives were voting members on the board. Swedish Match's president and CEO, Sven Hindrikes, appointed in 2004, was also a member of the board. Hindrikes had asked Dahlgren to propose a detailed financial policy first to the board's audit committee and then to the full board in its October 25 meeting. The board would decide on a financial policy, including how to measure leverage and what targets to apply. Several factors played into Dahlgren's sense that this was a good time to reconsider the company's financial policies. First, Sweden had recently instituted a new corporation law that allowed firms to repurchase shares even if it resulted in negative consolidated book equity for the group. Second, a continuation of the current policy would reduce leverage in the next few years. In Dahlgren's view, Swedish Match faced several potential benefits of taking on more debt. Leverage reduced the corporate income tax bill As in the United States and many other countries, interest expenses were deductible from corporate income under Swedish tax law. The corporate income tax rate was 28%, where it was expected to remain. There were other advantages to higher leverage. Some viewed excess cash or debt capacity negatively, seeing them as potentially leading to waste and inefficiency Further, the act of issuing new debt might be seen as a sign of streneth Institutional investors corporate income tax bill. As in the United States and many other countries, interest expenses were deductible from corporate income under Swedish tax law. The corporate income tax rate was 28%, where it was expected to remain. There were other advantages to higher leverage. Some viewed excess cash or debt capacity negatively, seeing them as potentially leading to waste and inefficiency. Further, the act of issuing new debt might be seen as a sign of strength. Institutional investors seemed to agree with a more aggressive policy. In a survey of some large owners earlier that year, several had expressed support for increased repurchases. A Citibank analyst reported, "we expect the company to buy back SEK 9-12 billion in shares by the end of 2007." Dahlgren also felt that the lack of explicit financial targets created unnecessary uncertainty. Finally, looking to international peers (see Exhibit 7 for selected financials), Dahlgren noticed that many of them maintained high leverage. In contrast, Dahlgren also ticked off the disadvantages of debt in his head. Net income would be lower, because some of the firm's cash flows would go to interest payments. Raising new debt might also expose the firm to bond market conditions when needing to refinance. Additionally, taking on more debt would reduce financial flexibility going forward. Dahlgren also had to consider the risk to the firm's business. If the smokeless tobacco products faced more competition, the ability to pay interest payments or principal could be in doubt. A forced sale of assets, or even bankruptcy, was a possibility. Credit rating agencies would lower Swedish Match's credit rating accordingly. Dahlgren and finance vice president Joakim Tilly discussed a bond issue in the European market, given the modest size of the Swedish bond market. Based on conversations with bankers in London, they felt that bond issues below 300 million, or approximately SEK 3 billion, would be impractical and expensive to issue. Such a bond would have interest and principal repayments in euros, but it would be fairly easy to swap those payments with a bank so that Swedish Match could pay interest in SEK. The effective interest rate after swapping was expected to be similar to euro rates. Analysts expected EBITDA to be around SEK 3 billion per year in the next few years. Given this, Dahlgren and Tilly thought that a BBB+ rating would be sustainable under as much as SEK 4 billion of additional debt. Swedish Match's board wanted to be conservative, and thought that it was important to be prepared for a worst-case scenario where profitability dropped by as much as half. Dahlgren and Tilly thus felt it was prudent to consider a temporary drop in EBITDA to as low as SEK 1.5 billion. Swedish Match shares were currently trading at SEK 80 in Stockholm, slightly up over the year to date Decision Dahlgren and Tilly believed that sensitivity analyses, theoretical valuation impacts, signaling considerations, and the availability of financing should be key inputs into the decision. Dahlgren elaborated: "Financial risk can ultimately be defined as the risk for a company of either failing to pay the interest on its loans or failing to pay back the entire principal at maturity traditional solvency ratios such as equity over total assets poorly reflect these risks." Instead, he felt that a policy that targeted a rating such as BBB+, a reasonable interest coverage ratio, and suitable market leverage would provide a better target for the firm Under this approach, he felt that substantially higher leverage could be maintained Taking on more debt and repurchasing shares might involve pushing book equity below zero, but the new corporation law was widely understood to allow this, and Dahlgren felt that financial analysts and investors would not find this unsettling would provide a better target for the firm. Under this approach, he felt that substantially higher leverage could be maintained. Taking on more debt and repurchasing shares might involve pushing book equity below zero, but the new corporation law was widely understood to allow this, and Dahlgren felt that financial analysts and investors would not find this unsettling, Yet Dahlgren understood that the board would raise several concerns about the proposal. Would the new leverage affect the firm's ability to undertake acquisitions? Would the firm's ability to repay its debt be robust even in a cyclical downturn? Dahlgren would need to address all of these concerns in the upcoming meeting. As Dahlgren considered the pros and cons of a new financial policy, he also pondered the appropriate amount and structure for a bond issue. 2009 2001 2002 2004 13.036 7,100 11 523 6.647 3.035 1.851 543 1,300 427 13.007 7027 1630 2.344 1.569 1201 270 13.635 7627 3.843 2.165 670 1.495 407 752 1,540 580 1.251 13543 7.451 3.ME 2.350 551 1,699 337 754 2.126 648 1.478 303 3.722 2211 365 1.540 200 911 2,174 572 1.602 309 1.NGS 200 1620 3,421 1.345 2.000 1.710 556 1.154 authored for by Wan Montoy in FIN 20.2025 y DOMNIOUEMADOER Dec 2021 2.960 5.730 2570 5015 16.261 1.600 8.587 2.970 5450 16.623 2006 5,310 22 254 15,102 3.000 4 MM 2.712 4300 14.80 Exhibit 2 Swedish Match. Selected Financial Data, 1995-2004 (in SEK millions, except where noted) 19 Summary Operating Data Revenue 7.435 7415 7.455 8.194 9420 - Cost of Goods Sold 3.900 3.63 Other Operating Expenses 3615 4006 5.130 2.062 2.179 EBITDA 2.6.20 2.280 2.639 1.473 1,584 1,643 1473 -Depreciation and Amortation 294 268 ERIT 332 381 -Interest Expense 1,179 1.314 1,146 1,262 107 178 132 Other Theme 504 394 302 234 EBT 4.341 1,576 - Income Tax Expense 1.530 1.558 1,198 5,280 473 439 512 630 Net Income 1,103 1,091 1,046 716 4.642 Balance Sheet Cash and Short-term investments 304 942 560 2,878 7.200 Current Assets 3.000 3.108 3.278 4,000 3.800 PPSE 2002 Other Assets 1.030 2.050 2.239 1.566 761 Total Assets 1.21 1.350 3.700 6.646 6,877 7.132 10.562 16,670 Current 4.566 2.790 3.248 2.732 3,200 Total Interest-Bang Debt 129 1019 209 5.873 4331 of which: Long-term Debt 9 209 2098 5093 Other Lab 289 890 63 1.191 1.405 Equity Including minority interest 1.682 2.368 2.992 2.300 6.102 Total Liabilities and Equity 6,640 8.877 7,132 10,562 16,670 Cash Flow Date and Stock Price Capital Expenditures 303 292 300 452 Cash Acquisitions et 0 50 157 2250 Dividends Pad 1,072 300 510 510 174 Share purchase 0 0 1.147 0 Share Outstanding 431 454 431 Year End Share Price (kronshare) 29.7 200 25.52 28 Market Value of Equity 12.001 12.331 12,180 10.990 12.30 Selected Growth Rates and Ratios EBITDA Morg 190 21.4% 21.0% 180W 1745 EBIT Margin 1594 177 174 14 ON 13:45 Book Leverage (det plus) 7.24 30.1% 052 400 Mark Levenge et plus matapital (1) TON 70 17 28 323 book Equity Amet 250 4201 2191 ON Catalowed September 2011 and malepon 2010 5.742 2.938 4.751 15.447 3.093 5.200 4518 2.378 400 15.47 3.778 3.10 2.559 3.79 5.43 5072 2100 472 16.623 5.000 618 2.125 5.204 16.281 2009 5351 4535 2,105 4607 16.102 5.000 14.30 331 033 751 217 150 92 539 1967 375 42 15.944 400 1.100 350 80.00 son 490 6105 20801 64 588 68 1221 78 535 1.012 2005 7871 25.05 350 34 229 24.150 170 16.0 11 52 203 20 15 110 53.09 1 293 172 125 SON 30 30.45 11 53 172 1829 143 4115 11 SON + Exhibit 3 Swedish Match Share Price Performance Relative to Sweden's Primary Share Index, January 2, 1997-September 1, 2005 100 90 80 mweny 70 60 ve 50 40 Swedish Krona (SEK) wo 30 Batam 20 10 1/2/1997 1/2/1998 6561/2/ 1/2/2001 1/2/2002 1/2/2003 1/2/2004 1/2/2005 1/2/2000 SWEDISH MATOS OMX STOCKHOLM 30 Source Thomson Reuters accessed October 2011 and company website, accessed March 2012 Exhibit 4 European Corporate Bonds, Constant Maturity Yields by Credit Rating January 2005 Maturity 5 year 3-month 6-month 1-year 10-year 20-year 30-year Credit AAA AA A BBB Benchmark 2.179 2.246 2.284 2.463 2.065 2.218 2.262 2.336 2.484 2.119 2.348 2.389 2.474 2.688 2 225 3.150 3.269 3.349 3.819 3.028 3.762 3.918 4,024 4.541 3.695 4.394 4.612 4.624 5.151 4.293 N/A 4.539 4.970 5.077 4.383 Source Bloomberg, accessed September 2011 Benchmark interest rate refers to the average of euro-area AAA-rated government debt (sovereign bonds issued by France and Germany) Exhibit 5 U.S. Industrial Firms, Aggregate Average Financial Ratios by Credit Rating, 2002-2004 Credit Rating BBB BR AAA AA A B 23.8 25.5 19.5 24.6 8.0 10.2 1.6 4.7 6.5 EBIT interest coverage (x) EBITDA interest coverage (*) Total debUEBITDA (x) Market leverage (debt/debt plus market capitalization) (%) 2.5 3.5 3.5 1.2 1.9 0.4 0.9 0.4 0.9 22 53 79 3.1 72 16.1 24.5 35.5 53.5 782 Source Compiled from Standard & Poor's Rating Direct "CreditStats Adjusted Key US Industrial Financial Ration." August 11, 2005, pp. 3-4, accessed September 2011 Exhibit 6 Swedish Match's Board of Directors, August 2005 Bernt Magnusson: Chairman of the Board Jan Blomberg: Former CFO, Pharmacia Kenneth Ek Labor representative Sven Hindrikes: President and CEO Tuve Johannesson: Former president, Volvo Cars Arne Jurbrant: Former CEO, Kraft Foods Nordic Region Eva Larsson: Labor representative Joakim Lindstrm: Labor representative Karsten Slotte: President and CEO of snack food company Cloetta Fazer Kersti Strandqvist: Business area manager, SCA Baby Care Meg Tivus: President lottery operator Svenska Spel Exhibit 7 Comparable Company Data, 12/31/2004 (in SEK millions, except as noted) Swedish Match Imperial Tobacco UST BAT Gallaher Altadis 13,007 2344 1.865 286 2.083 28% 11,888 6,377 6,060 551 3,527 65% 38.447 15.915 12.189 2.741 5,349 73% 137.096 36,528 31,982 4.723 35 993 30% 32.428 8,811 7,677 1,974 4,558 55% 86,469 9,624 8.112 1,496 4,852 45% 3.002 14.898 3,529 6,309 5,060 3,390 11.027 8.238 2726 64 4.010 77,282 50,549 23,664 3,069 24.662 226,308 91,353 57,074 77.881 9,689 55,154 37831 18.087 -754 9,954 96.446 27.720 55,893 12.833 Summary Operating Data Net Sales EBITDA EBIT Interest Expense Net Income Dividend Payout Ratio (%) Balance Sheet and Cash Flow Data Cash and Short-term Investments Total Assets Total Debt Non-Interest Bearing Liabilities Total Equity Stock Price Data Price/Earnings Ratio Equity Market Value Select Ratios Sales Growth EBITDA Margin Leverage at Book Values (debt debt plus equity) () Leverage at Market Values (debt/debt plus market cap) ( EBIT interest Coverage (x) EBITDA Interest Coverage (x) Total DebUEBITDA (*) Credit Rating 14.2x 28.454 15. Ox 52,823 23. 4x 131.484 17.6% 233,667 17.9% 65,865 23.1x 86,425 -0.2% 5.3% 54% 99% 18% -53% 44% 94% 1.8% 27% 54% -15% 27% 102% 2.5% 11% 68% 41% 11% 13% 28% 28% 36% 24% 5.4 70 88 15 110 11.6 1.3 58 32 68 77 25 39 4.5 4.3 29 BBB A- BBB A BBB Source Thomson Reuters, except credit rating data from Standard & Poor's Ratings Direct accessed September 2011 Question 3 (10 Points) Dahlgren believes that if Swedish Match moves forward with the transaction it would likely receive a credit rating of BBB by S&P. Do you share Dahlgren's view or not? Explain your answer. (Hint: To answer this question, I would like you to calculate some of the metrics in Exhibit 5 for Swedish Match under the new proposed financial policy.) Exhibit 5 U.S. Industrial Firms, Aggregate Average Financial Ratios by Credit Rating, 2002-2004 Credit Rating BBB BB AAA AA A B 238 1.2 19.5 24.6 0.9 25.5 0.4 EBIT interest coverage (x) EBITDA interest coverage (*) Total debUEBITDA (X) Market leverage (debt/debt plus market capitalization) (%) 8.0 10.2 1.6 4.7 6.5 22 1.9 25 3.5 3.5 0.4 0.9 7.9 5.3 3.1 7.2 16.1 24.5 35.5 53.5 782 Source: Compiled from Standard & Poor's Rating Direct "CreditStats Adjusted Key US. Industrial Financial Ration" August 11, 2005, pp. 3-4 accessed September 2011 A New Financial Policy at Swedish Match In early September 2005, Lars Dahlgren was weighing his options in his Stockholm office. He had recently been appointed CFO of Swedish Match, a producer of smokeless tobacco, cigars, matches, and lighters. Its most important product was a type of smokeless tobacco called smus* (see Exhibit 1). At the next meeting of Swedish Match's audit committee, Dahlgren was scheduled to present an annual review of the financial plan. Swedish Match had recently used bank loans to finance the acquisition of several cigar firms. However, these debts were being rapidly paid off, and if the firm maintained its traditional policies, its leverage--the ratio of debt to capital --would soon be very low again. Though the board did not know it yet, Dahlgren was considering a radical proposals a substantial increase in the firm's leverage, implemented with a Furo-denominated bond issue, and combined with an aggressive program of share repurchases. This would be a sea change from the firm's more conservative financial practices. After the audit committee meeting, Dahlgren would propose the new policy to the full board in its October meeting Swedish Match and the Match King Swedish Match had a long and dramatic history, much of it under the leadership of Ivar Kreuger, Bom in 1880, Ivar Kreuger - "the Match King" - was one of the wealthiest men in the world when he killed himself in March 1932. Kreuger had become wealthy by building Swedish Match into an international business empire comprised of national monopolies in safety matches. At the time of his death, Swedish Match had a globally dominant position, selling 66% of the world's matches! After graduating from the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm with a degree in mechanical engineering, Kreuger had traveled the world between 1900 and 1907 working in various jobs in Mexico, South Africa, and New York City, where he first learned of steel-reinforced concrete He returned to Europe in 1908, founding a building company that applied the new construction the Swedish Match name. The firm's owner spun off Swedish Match in an IPO in 1996. At that time, the business consisted of matches and lighters, cigarettes, and niche tobacco products (cigars, pipe tobacco, and smokeless tobacco). In 1999, the company divested its remaining cigarette operations to concentrate on niche tobacco products. The firm made acquisitions in cigars, notably of General Cigars, headquartered in Virginia, in 1999. The divestment of cigarettes was a strategic move. In the Swedish market more and more people felt there were advantages to snus, a more socially accepted tobacco product, and Swedish Match was uniquely positioned to take advantage of this growth (Exhibit 2 shows summary financial data for the decade ending in 2004.) Swedish Match in 2005 By 2005, Swedish Match was a worldwide leader in smokeless tobacco products including snuff. snus, and chewing tobacco. The tobacco was sourced from carefully selected suppliers and manufactured in Sweden. These business segments accounted for 32% of 2004 sales and 72% of operating income. These products were most popular in Scandinavia and the United States Snus had been banned in the EU since 1992, but it remained legal in Sweden. Its sale was also allowed in Norway, which remained outside the EU. The EU debated the regulatory status of snus, and a general trend emerged of increased tobacco restrictions as well as concern about possible future regulatory restrictions. However, some analysts argued that snus faced lower regulatory risks than cigarettes because the health risks were different In Sweden and Norway, about one million people used snus in 2004, and Swedish Match controlled 96% of the market in Scandinavia, popular snus brands such as General, Goteborgs Rape Ettan, and Catch held a dominant market position, Sweden was unique in the EU with its low prevalence of cigarette smoking Among Swedish men, the use of snus was more common than smoking cigarettes Growth was also stimulated by the fact that the EU decided to remove the cancer warning from the snus can in 2002. With attractive margins and strong growth prospects, several competitors surfaced during this time on the Swedish market The United States was the biggest growth market for smokeless tobacco products, with over 900 million cans of snuff and snus sold in the US in 2004. In the United States, Swedish Match offered moist snuff brands Longhom and Timberwolf and the snus brand General. The primary brands competing in the US market included Grizzly. Hawken, and Kodiak, all produced by American Snuff Company, and Red Seal, Copenhagen, Rooster, and Skoal, produced by US, Smokeless In addition to snus, snuff, chewing tobacco, and cigars, Swedish Match also produced pipe tobacco, although this was a declining market (it shrunk 14% in US, sales volume in 2004, for example). Pipe tobacco accounted for about 9% of the company's operating income. Swedish Match maintained a 16% market share in the US and profitability for pipe tobacco remained strong." Finally, matches accounted for just 11% of the company's sales in 2004 and 1% of operating income. Overall, Scandinavia, the US and the rest of the world each represented approximately one-third of company sales. Costs matched revenues fairly well, so the net currency exposure of Swedish Match was low Swedish Match had a conservative policy in all financial matters. At the time of the firm's IPO in 1996, management had decided to target book equity of at least 30% of assets (corresponding to interest-bearing debt over assets of 20%-40%, depending on the amount of non-interest-bearing liabilities). The firm paid high dividends and made some share repurchases. For a period, leverage had increased due to acquisitions in the cigar area. The company had an international short-term bond program (the "Global Medium Term Note Program") and a small Swedish bond program, both started in the late 1990s and by then largely paid off. The firm had a credit rating of A- from rating agency S&P" (see Exhibit 5 for data on ratings) A New Financial Policy Swedish Match's financial policy was set by the board of directors (see Exhibit 6 for a list of members). In accordance with Swedish law, two labor representatives were voting members on the board. Swedish Match's president and CEO, Sven Hindrikes, appointed in 2004, was also a member of the board. Hindrikes had asked Dahlgren to propose a detailed financial policy first to the board's audit committee and then to the full board in its October 25 meeting. The board would decide on a financial policy, including how to measure leverage and what targets to apply. Several factors played into Dahlgren's sense that this was a good time to reconsider the company's financial policies. First, Sweden had recently instituted a new corporation law that allowed firms to repurchase shares even if it resulted in negative consolidated book equity for the group. Second, a continuation of the current policy would reduce leverage in the next few years. In Dahlgren's view, Swedish Match faced several potential benefits of taking on more debt. Leverage reduced the corporate income tax bill. As in the United States and many other countries, interest expenses were deductible from corporate income under Swedish tax law. The corporate income tax rate was 28% also expose the firm to bond market conditions when needing to refinance. Additionally, taking on more debt would reduce financial flexibility going forward. Dahlgren also had to consider the risk to the firm's business. If the smokeless tobacco products faced more competition, the ability to pay interest payments or principal could be in doubt. A forced sale of assets, or even bankruptcy, was a possibility. Credit rating agencies would lower Swedish Match's credit rating accordingly. Dahlgren and finance vice president Joakim Tilly discussed a bond issue in the European market, given the modest size of the Swedish bond market. Based on conversations with bankers in London, they felt that bond issues below 300 million, or approximately SEK 3 billion, would be impractical and expensive to issue. Such a bond would have interest and principal repayments in euros, but it would be fairly easy to swap those payments with a bank so that Swedish Match could pay interest in SEK. The effective interest rate after swapping was expected to be similar to euro rates. Analysts expected EBITDA to be around SEK 3 billion per year in the next few years. Given this, Dahlgren and Tilly thought that a BBB+ rating would be sustainable under as much as SEK 4 billion of additional debt. Swedish Match's board wanted to be conservative, and thought that it was important to be prepared for a worst-case scenario where profitability dropped by as much as half. Dahlgren and Tilly thus felt it was prudent to consider a temporary drop in EBITDA to as low as SEK 15 billion Swedish Match shares were currently trading at SEK 80 in Stockholm, slightly up over the year to date. Decision Dahlgren and Tilly believed that sensitivity analyses, theoretical valuation impacts, signaling considerations, and the availability of financing should be key inputs into the decision. Dahlgren elaborated: "Financial risk can ultimately be defined as the risk for a company of either failing to pay the interest on its loans or failing to pay back the entire principal at maturity... traditional solvency ratios such as equity over total assets poorly reflect these risks." Instead, he felt that a policy that targeted a rating such as BBB+, a reasonable interest coverage ratio, and suitable market leverage would provide a better target for the firm. Under this approach, he felt that substantially higher leverage could be maintained. Taking on more debt and repurchasing shares might involve pushing book equity below zero, but the new corporation law was widely understood to allow this, and Dahlgren felt that financial analysts and investors would not find this unsettling Yet Dahlgren understood that the board would raise several concerns about the proposal. Would a considerations, and the availability of financing should be key inputs into the decision. Dahlgren elaborated: "Financial risk can ultimately be defined as the risk for a company of either failing to pay the interest on its loans or failing to pay back the entire principal at maturity traditional solvency ratios such as equity over total assets poorly reflect these risks." Instead, he felt that a policy that targeted a rating such as BBB+, a reasonable interest coverage ratio, and suitable market leverage would provide a better target for the firm. Under this approach, he felt that substantially higher leverage could be maintained. Taking on more debt and repurchasing shares might involve pushing book equity below zero, but the new corporation law was widely understood to allow this, and Dahlgren felt that financial analysts and investors would not find this unsettling Yet Dahlgren understood that the board would raise several concerns about the proposal. Would the new leverage affect the firm's ability to undertake acquisitions? Would the firm's ability to repay its debt be robust even in a cyclical downturn? Dahlgren would need to address all of these concerns in the upcoming meeting. As Dahlgren considered the pros and cons of a new financial policy, he also pondered the appropriate amount and structure for a bond issue Learning Objectives & Instructions In this assignment you will analyze the proposed change in the financial policy of Swedish Match. The case is set around September 2005. During this time period Lars Dahlgren, the CFO of Swedish Match, is considering a radical change in the firm's financial policy. Specifically, Dahlgren is considering whether to increase the leverage of the firm through a bond issuance, and using the money raised from the bond issuance to repurchase shares. As part of this assignment you will analyze whether this transaction will ultimately be to the benefit of Swedish Match's shareholders. Additionally, this assignment asks you to discuss the benefits and costs associated with debt financing. This case study is slightly more qualitative in nature compare to the last one. Therefore, it is especially important that you read the entire case study in the course packet carefully before attempting to answer the questions below. You might have to read the case study several times to make sure you have all the information that you need. All of the information you require to solve this assignment is in the course packet (see syllabus) You may work on this case study independently or in groups of up to four students. If you work in groups, please only hand in one copy of your write-up per group and make sure to list the full names of all your group members. You will hand in a type written copy of your write-up at the beginning of class on the due date. The first page should have the title "FIN 320 - Swedish Match Case" and list your full namels). I will not accept late submissions or hand written submissions, or submissions by email Please follow the following additional instructions when completing the assignment Assume a corporate tax rate of 28% for Swedish Match Assume that Swedish Match has no excess cash Assume that if Swedish Match completes the transaction it will issue a perpetual bond with a face value of SEK 4 billion Assume that the yield on a perpetual bond equals the yield on a 30 year bond Question 3 (10 Points) Dahlgren believes that if Swedish Match moves forward with the transaction it would likely receive a credit rating of BBB by S&P. Do you share Dahlgren's view or not? Explain your answer. (Hint: To answer this question, I would like you to calculate some of the metrics in Exhibit 5 for Swedish Match under the new proposed financial policy.) A New Financial Policy at Swedish Match In early September 2005, Lars Dahlgren was weighing his options in his Stockholm office. He had recently been appointed CFO of Swedish Match, a producer of smokeless tobacco, cigars, matches, and lighters. Its most important product was a type of smokeless tobacco called snus" (see Exhibit 1). At the next meeting of Swedish Match's audit committee, Dahlgren was scheduled to present an annual review of the financial plan. Swedish Match had recently used bank loans to finance the acquisition of several cigar firms. However, these debts were being rapidly paid off, and if the firm maintained its traditional policies, its leverage- the ratio of debt to capital - would soon be very low again Though the board did not know it yet, Dahlgren was considering a radical proposal: a substantial increase in the firm's leverage, implemented with a Euro-denominated bond issue, and combined with an aggressive program of share repurchases. This would be a sea change from the firm's more conservative financial practices . After the audit committee meeting, Dahlgren would propose the new policy to the full board in its October meeting a Swedish Match and the Match King Swedish Match had a long and dramatic history, much of it under the leadership of Ivar Kreuger. Born in 1880, Ivar Kreuger-"the Match King" - was one of the wealthiest men in the world when he killed himself in March 1932. Kreuger had become wealthy by building Swedish Match into an international business empire comprised of national monopolies in safety matches. At the time of his death, Swedish Match had a globally dominant position, selling 66% of the world's matches.! After graduating from the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm with a degree in mechanical engineering, Kreuger had traveled the world between 1900 and 1907 working in various jobs in Mexico, South Africa, and New York City, where he first learned of steel-reinforced concrete. He retumed to Europe in 1908, founding a building company that applied the new construction . technique. The firm, Kreuger & Toll, grew to be worth SEK 1 million by 1911. Matches were the Kreuger family business, however, and Kreuger soon turned his attention there. In 1903, Sweden had 15 match companies. Six of these merged to form Jnkping och Vulcans Tndsticksfabriks AB (J&V). controlling 80% of the Swedish match market and threatening the Kreuger family company. Using contacts in the banking industry and his construction profits, Ivar Kreuger was able to raise debt to finance an expansion of the family's company. He used bank loans to merge Sweden's nine remaining match companies in 1913 into AB Frenade Svenska Tndsticksfabriks (Frenade), with Kreuger in control. During World War 1. J&V sold matches to both sides of the conflict. When the Allies initially Britain, France, and Russia) suspended J&V import licenses, Frenade, which had sold matches only to the Allied side, benefitted. In 1916, J&V was forced to merge with Frenade, forming Swedish Match. Ivar Kreuger had gained complete control over the Swedish market for matches The monopoly in Sweden proved highly profitable, and Kreuger set out to replicate it elsewhere. As a first step, in 1917, Swedish Match acquired majority holdings in Denmark's three match companies, but this tested Kreuger's ability to borrow in Sweden to the limit. To continue expanding Kreuger needed funding beyond the capacity of Swedish banks. In 1923, Kreuger set up the International Match Company (IMCO) in New York City as a way to raise money from American investors Raising equity abroad threatened to put Kreuger in violation of Swedish laws that forbade foreign majority ownership of Swedish companies. To avoid this, Kreuger invented "A" and "B" share classes: B shares gave investors only a small percentage of the voting rights of an A share, allowing investors to buy stock in Kreuger's companies without violating Swedish law. Dual share classes of this type are still in common use around the world. Kreuger also pioneered the use of convertible securities-loans that could be repaid in cash or converted to company stock? By 1925, Swedish Match controlled significant portions of the match industries of Austria. Belgium, Finland, Hungary, Norway, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, and soon thereafter made acquisitions in Japan and the US. Creating national monopolies often required permission from national governments. Beginning in 1925, Kreuger began lending money to governments in exchange for monopoly control of their match markets, Ecuador, France, Germany Greece Hungary, Latvia, Peru, Poland, and Yugoslavia all borrowed money from Kreuger, Swedish Match, IMCO, and the other companies in Kreuger's empire. Kreuger raised ever larger sums in New York. Investors were willing to supply funds for two reasons the high and stable dividends paid to investors, and the national monopolies that sustained these payouts. Kreuger became world famous. The stock market crash in 1929 and the worsening business cycle made things harder for Kreuger, Profitability at Swedish Match faltered as the Great Depression deepened. However, Kreuger's national governments. Beginning in 1925, Kreuger Beyan for monopoly control of their match markets, Ecuador, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Peru, Poland, and Yugoslavia all borrowed money from Kreuger, Swedish Match, IMCO, and the other companies in Kreuger's empire. Kreuger raised ever larger sums in New York. Investors were willing to supply funds for two reasons: the high and stable dividends paid to investors, and the national monopolies that sustained these payouts. Kreuger became world famous. The stock market crash in 1929 and the worsening business cycle made things harder for Kreuger. Profitability at Swedish Match faltered as the Great Depression deepened. However, Kreuger's companies continued paying high dividends to attract new investors. As money ran out, Kreuger paid dividends to his earlier investors with money received from new investors. He covered this up with fraudulent accounting practices and counterfeit documents. This worked for a while, but when Kreuger tried to sell his majority stake in the telecommunications giant Ericsson, an audit by the bankers at J.P. Morgan revealed that some assets were missing. The bank blocked the deal in February 1932, initiating one of the largest financial collapses of all time. All sources of debt funding dried up for Kreuger. The Swedish Match share price collapsed. Within a few weeks, Ivar Kreuger shot himself in a Paris hotel, generating worldwide news.? Swedish Match survived. In the wake of the collapse, the company divested several businesses and focused on matches in Sweden. Over the next 50 years, Swedish Match was owned by a succession of Swedish investors and business groups who operated the match business under various names. By 1992, this match business was combined with the largest Swed