Question: Harley-Davidson: Preparing for the Next Century There are very few products that are so exciting that people will tattoo your logo on their body. Richard

Harley-Davidson: Preparing for the Next Century

There are very few products that are so exciting that people will tattoo your logo on their body. — Richard Teerlink, Retired CEO, Harley-Davidson

In 2003 Harley-Davidson, under the leadership of Jeffery Bluestein, celebrated its 100th birthday. The company, which almost went bankrupt in 1970, had successfully shed its product and marketing doldrums and was once again the market leader of the U.S. heavyweight motorcycle industry. For the last 18 years the company had led the industry in retail sales with a commanding lead of 50% market share in the United States and 32% globally. Noted Fortune: “Harley . . . ranks among America’s top growth stocks since its 1989 IPO [initial public offering]. Its 37% average annual gain runs just behind the 42% pace of another ‘86 debutante: Microsoft.”1

While the company’s successful history was in his thoughts, Bluestein was aware of the formidable issues facing him and his top management team. The company’s customer base had grayed considerably since the early 1990s, and the average age of Harley riders rose from 35 to 47 years in the past decade. Younger Americans (25- to 34-year-old men) seemed to prefer the light sports bikes offered by Suzuki, Honda, Yamaha, and Kawasaki. Bluestein recognized these concerns by noting: “The only thing that can stop us is if we get complacent. Even though we’ve been successful, we can’t stand still.”

On April 25, 2005, the company’s stock price declined 17%, despite an increase in first-quarter profits and company sales. The steep decline was in response to the company’s revised estimates for planned 2005 sales; the company lowered its sales estimate by 10,000 units and noted that it planned to make 329,000 units for the year. The need to reexamine or change strategy became more urgent.

1 “Will Harley-Davidson hit the wall?” Fortune, August 12, 2002.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Professor Richard L. Nolan, William Barclay Harding Professor of Business Administration (Emeritus), Harvard Business School and Philip M. Condit Endowed Chair, University of Washington Business School, and Professor Suresh Kotha, Oleson/Battelle Endowed Chair, University of Washington, prepared this case. HBS cases are developed solely as the basis for class discussion. Cases are not intended to serve as endorsements, sources of primary data, or illustrations of effective or ineffective management

Copyright © 2006 President and Fellows of Harvard College. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, call 1-800-545-7685, write Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston, MA 02163, or go to http://www.hbsp.harvard.edu. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the permission of Harvard Business School.

The Early Years[1]

Arthur and Walter Davidson and William Harley founded Harley-Davidson in 1903 to build motorcycles in a garage. Having sold 50 motorcycles, the company filed for incorporation in 1907 with one full-time employee. During these early years, the reputation of the company was linked to Walter Davidson’s riding a Harley motorcycle to victory in a 1908 race and innovations such as the Vtwin engine, clutch, internal expanding rear brake, and three-speed transmission that the company pioneered. This race was one of many that Harley would eventually go on to win as it transformed itself into the world’s leading producer of motorcycles.

By 1918 Harley-Davidson became the world’s largest motorcycle company by producing 28,000 motorcycles. During the 1920s, despite a sagging economy, Harley-Davidson invested in research and development (R&D), experimented with its now famous V-twin design, built a new four-cylinder engine, and focused on improving the reliability of its machines. With the addition of the firmdeveloped electric starter, balloon tires, front brakes, and standardized parts, product quality also improved. With such innovations, consumers chose Harley motorcycles, 2 to 1, over those of the firm’s archrival, the Indian, the only other U.S. motorcycle manufacturer.

Post World War II, the company’s sales declined, and Harley-Davidson experienced pressure from imports from Europe.[2] However, Harley managed to remain profitable by introducing larger, more powerful motorcycles and, by the mid-1950s, became the undisputed leader of the market with over 60% market share.

The Harley-Davidson Mystique

Throughout its early history, Harley-Davidson established an image of “raw power,” which became its major selling point. The most distinctive feature of Harley was the V-twin engine. Introduced in 1909, the V-twin engine derived its name from its cylinders, which were set opposite one another at a 45-degree angle. It gave Harley motorcycles an aggressive appearance of raw power and the ability to deliver broad but low-torque power. The V-twin engine’s simple design allowed owners to tinker with their engines—a necessity at that time, since motorcycle mechanics were virtually nonexistent. Harley’s heavy use of chrome, its low-profile appearance, the styled tail fenders, and the chop of the front fork (i.e., the extension of the fork beyond plumb) also highlighted the firm’s unique image. The Harley motorcycle not only looked different, it sounded different. The growl of the Harley engine was, and still is, described as “a voice: a bassoprofundo thump that makes other motorcycles sound like sewing machines.”[3]

With the addition of new colors, decals, and stylized designs in the late 1930s, Harley adopted an “image and lifestyle” approach to marketing. (Prior to the 1930s, advertisements marketed the motorcycles as utilitarian vehicles.) Its motorcycles were advertised in “biker” magazines and promoted mainly by word of mouth. Harley motorcycles were used by the U.S. military, highway patrol officers, the Hell’s Angels, and Hollywood rebels, including actors James Dean and Marlon

2

Brando. In the late 1950s, this roster expanded to include young “Elvis types” attracting dates with their Harley motorcycles. Given this customer base, the firm’s advertisements often depicted leatherclad riders, military dispatch riders, or police officers on motorcycles. These advertisements cultivated an image of Harley motorcycles as tough because they were often associated with people who were willing to break the traditional mold or willing to live on the edge. The image reflected rugged individuality and the frontier spirit of the United States. Over time, the Harley motorcycle became a part of American iconography and was associated with the U.S. flag and the bald eagle, America’s national symbol. This association resulted in unprecedented brand loyalty, especially among U.S. customers, that continues to this day. A typical Harley motorcycle owner cites its American manufacture and character as its most attractive and distinguishable feature.

The Japanese Enter the U.S. Market

During the late 1950s, the U.S. market attracted Japanese motorcycle manufacturers, beginning with Honda. In 1959, Honda accidentally uncovered a large untapped customer base of older males and younger women—a segment not well suited to the “tough” Harley motorcycles. To capture this segment, Honda established a more benign, family-oriented approach in advertising motorcycles. Its ad campaign, “You meet the nicest people on a Honda,” was communal, sweet, and family oriented. Honda focused on smaller, faster, quieter, and less-expensive motorcycles. It entered one geographic region at a time with lightweight motorcycles (50 cc) and then introduced powerful 250-cc motorcycles before targeting another region. By 1965, Honda had made substantial inroads; one out of every two motorcycles sold during that year in the United States was a Honda.

Other Japanese firms, Yamaha, Suzuki, and Kawasaki, soon followed. Similar to Honda, they marketed smaller, quieter, and more fuel-efficient motorcycles that required little or no maintenance and were easier to handle compared to Harley bikes (Harley motorcycles weighed between 450 and 800 pounds). These characteristics attracted younger riders, women, and older riders; riders who could not afford the more expensive Harley motorcycles; bikers who did not want to tinker with the motorcycles; and those who could not muscle them around steep curves.

With the Japanese manufacturers’ entry, the size and demographics of the U.S. motorcycle industry changed significantly. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the demand for motorcycles grew rapidly. For example, 80% of motorcycle sales in the early 1960s were to first-time buyers, and between 1963 and 1973 motorcycle sales increased at an annual rate of 33%. Soon Japanese manufacturers accounted for more than 85% of U.S. motorcycle sales.

Led by Honda, the Japanese manufacturers were skilled at mass-producing motorcycles efficiently. They constantly improved and redesigned their products to counter potential market threats, and they reduced the time it took to introduce newer models. Their ability to rely on internally generated funding, sourced primarily from Keiretsu banks, created a long-term profit orientation. Prices were set to increase market share with little regard to short-term profits, and advertising expenditures were many multiples of competitor companies. Consumers preferring the technical advances being offered by the Japanese motorcycle manufacturers flocked to them. During this time, few, if any, technological improvements were made to Harley motorcycles.

Despite increasing sales, Harley’s overall market share declined, and it was transformed into a “niche” player. In 1965, to raise capital for new products and expand production, the firm went public after 60 years of private ownership. But unable to attract enough capital, the firm continued to face severe pressures. Shortly after going public, Harley-Davidson was acquired in a friendly takeover by AMF, a heavy-industrial conglomerate looking to diversify into leisure products.

Imitating the Japanese

Upon acquiring Harley-Davidson, AMF’s CEO, Rodney Gott, noted: “There was a motorcycle craze. You could sell anything you could produce. We wanted to meet [this] demand.”[4] The influx of new capital from AMF allowed Harley-Davidson to expand production from 15,475 units in 1969 to 70,000 units in 1973. Less-skilled workers were added to the production lines. In AMF’s zeal to increase production, many quality issues were overlooked. Product quality decreased to an all-time low. Richard Teerlink, the firm’s CFO during that time, commented on this process of decline: “In the early ‘80s, Harley’s reputation for reliability and quality had fallen as steeply as its market share, which had dropped from 100% of the domestic market to a low of 23%. Brand new Harleys sitting on the dealership floor had to have cardboard put down beneath them to sop up the leaking oil.”[5]

The Harley product that AMF had acquired was essentially a handcrafted machine. Production drawings used to build motorcycles were not exact and tolerances for the various components and processes not well specified. However, a skilled workforce was able to produce a small volume of quality products using craft methods of production. Rather than reevaluate their approach to manufacturing and product quality, AMF managers added new features in an effort to attract customers from new market segments.[6]

On the marketing side, AMF hired Benton & Bowles, a respected firm, to create advertising for all of AMF’s leisure products including Harley motorcycles. Benton & Bowles was interested in expanding Harley-Davidson’s share of the nontraditional market dominated by the Japanese. To change its image, AMF’s top management removed Harley’s advertisements from certain previously successful, but less “high-tone,” advertising outlets such as Easy Rider. This change in advertising tactics alienated Harley’s traditional customers—riders who were most likely to work on their own motorcycles, a necessity during this time as Harley’s quality declined.

The Japanese Target Harley-Davidson

In 1975, Honda introduced the Goldwing, a 1000-cc motorcycle. Industry reports during that time described this motorcycle as the most technologically sophisticated and complex heavyweight motorcycle available on the market. Soon Kawasaki followed suit with the introduction of its own heavyweight motorcycle. To Harley-Davidson’s horror, its share of the heavyweight segment began to decline. Harley-Davidson was now faced with a situation in which it was ceding ridership to the Japanese in the traditional biker segment and not attracting customers in nontraditional segments. By the late 1970s, due to the economic downturn, motorcycle demand dropped, forcing all manufacturers to compete for a bigger share of a stagnant market. Japanese manufacturers continued to pressure Harley-Davidson by introducing newer and larger motorcycles. Between 1970 and 1980, Harley-Davidson’s share declined by over 80%.

4

Transforming Harley

By 1980, with Harley’s profitability down, AMF began looking for a buyer. Vaughn Beals, the then CEO, orchestrated a highly leveraged buyout with the help of a small group of Harley-Davidson managers. Able to raise only a small fraction of the $81 million buyback price, Harley-Davidson’s top management took the rest on as debt. This debt forced Harley’s new owners to pare down costs and cut back motorcycle production. Their goal was simple: survival.

Benchmarking Honda

To benchmark the company against Honda, senior managers visited Honda’s Ohio plant in the United States. After touring the plant, Tom Gelb, the senior vice president for operations, recalled: “The [Honda] assembly line was neat and uncluttered—unlike our operation, where the line was always littered with parts and material. There was minimum paperwork and things flowed very smoothly.”[7] In the Honda plant, inventory was controlled through a just-in-time (JIT) system that used no computers or automation. Moreover, motorcycles were built to order rather than for inventory. This shocked Harley-Davidson executives, whose multimillion-dollar computerized inventory system at their York, Pennsylvania assembly plant required far greater amounts of buffer inventory for both work-in-process (WIP) and finished motorcycles. The computer-controlled inventory system Harley used had cost $2 million and moved inventory from storage to production via conveyors, which snaked over two miles within the plant.

Jeffrey Bleustein, the senior vice president for parts and accessories, acknowledged: “[The Japanese] . . . were just better managers . . . and they understood how to do manufacturing a hell of a lot better, with less inventory and much higher quality.”[8] Beals concurred: “Harley-Davidson’s production system was basically flawed. In this system, we gave the worker responsibility for quantity, not quality. Then we set up a whole police force for quality and a battalion of accountants to measure errors made in production.”[9]

The differences between Harley-Davidson and Honda were striking. For example, only 5% of Honda’s motorcycles failed to pass final quality inspection; over 50% of Harley’s failed during the same test. According to Harley-Davidson’s internal estimates, overall Japanese productivity was over 30% greater than at Harley-Davidson. According to a report by the Boston Consulting Group, Honda’s value-added per employee was even better, on the order of two to three times that of its Japanese competitors, Suzuki and Yamaha.

The Productivity Triad

Beals and his management team realized that Harley’s entire manufacturing system needed to be modified, and fast. Using Japanese production methods as a blueprint, top management teams formulated and implemented what they termed the productivity triad. This new approach involved

(a) employee involvement, (b) use of JIT inventory practices, and (c) statistical operator control (SOC).

First, line workers were encouraged to contribute to the decision-making process. Workers were required to participate in the newly formed quality circles that were made directly responsible for improving motorcycle quality. Second, a materials-as-needed (MAN) program, the company’s version of Honda’s JIT inventory control practices, was implemented to free up much-needed cash by reducing WIP inventory. It was hoped that lowering the inventory levels would make quality problems more apparent and force employees to take action. Third, under SOC, employees were taught to see how quality problems developed and how they could be traced and corrected during the production process. Harley’s top management hoped that process improvements utilizing tools that track conformance to specifications, coupled with employee incentive programs, would result in greatly improved product quality. Finally, in 1983, to gain time and protect itself from the Japanese inroads in the heavyweight segment, Harley-Davidson sought tariff protection from the U.S.

government. It was granted a five-year, self-liquidating tariff by then U.S. President Ronald Reagan.

These changes and the renewed R&D expenditures impacted the competitive capability of HarleyDavidson. For example, prior to the introduction of MAN, Harley-Davidson turned its inventory twice a year. Under the new system, inventory turn increased to 17 times a year. Additionally, productivity improvement went up by over 50%, work-in-process inventory was reduced by 75%, scrap and rework went down by 68%, U.S. revenues increased by over 80%, international revenues went up by 1.7 times, and operating profits increased by $59 million. Market share in the heavyweight segment, which had dropped earlier, now increased by 97%. The firm petitioned the U.S. government to lift the import tariff protection in 1987, a year ahead of schedule.[10]

During this time, Willie G. Davidson, the grandson of one of the founders, was responsible for product design and for keeping the company’s loyal and hard-core customers informed about the struggles, challenges, and changes at the company. In 1989, the firm went public through a wellreceived IPO. Teerlink, the firm’s CFO for six years, became CEO and chairman. Management and motorcycle enthusiasts attended the listing of Harley-Davidson on the New York Stock Exchange with a ceremony, replete with a motorcycle parade down Wall Street.

Continuing the Transformation

After the IPO, under Teerlink’s leadership, the company began to transform itself from an informal to a formal organization by emphasizing organizational and individual learning at all levels through a program it termed the Leadership Institute. Noted Teerlink:

The senior staff consists of me, my secretary, the CFO and our vice president of continuous improvement. The company eliminated the positions of senior vice president in marketing and in operations. We eliminated those jobs because they didn’t add value to our products. The people were auditors. They were checkers. Now we have teams—a create-demand team, a team that is in charge of producing our products, and a product-support team. Before Harley established these teams, people would go up to one boss and that boss would go over to another boss and he would go to still another boss. And we wondered why the Japanese beat us on the issue of time.[11]

6

To complement the organizational changes, new rewards and incentive systems were introduced. Noted Teerlink:

We are changing our pay system to pay for performance. We needed our people to understand empowerment. An employee must make the decision that he or she wants more training—no one will tap you on the shoulder—but once you are there, we will help you. The executive committee was the first group to go through the [Leadership] institute. We didn’t want anyone to get the attitude that the executive committee doesn’t have anything to learn. I’m a big believer in learning.[12]

Line workers were exposed to the interrelation among products, sales, and profitability. The company also prepared nontechnical explanations of how cash flows and flexible production affected financial success. Harley made substantial changes in worker job descriptions, responsibilities, and production processes to increase job enrichment and worker empowerment.[13]

In 1993 Harley-Davidson acquired a minority interest in the Buell Motorcycle Company, a manufacturer of performance motorcycles. Through this investment Harley hoped to enter select niches within the “performance” motorcycle market, which several top executives thought would return Harley to its heritage of product innovation and development through lessons from the racetrack.

Emergence of Harley Ownership Group

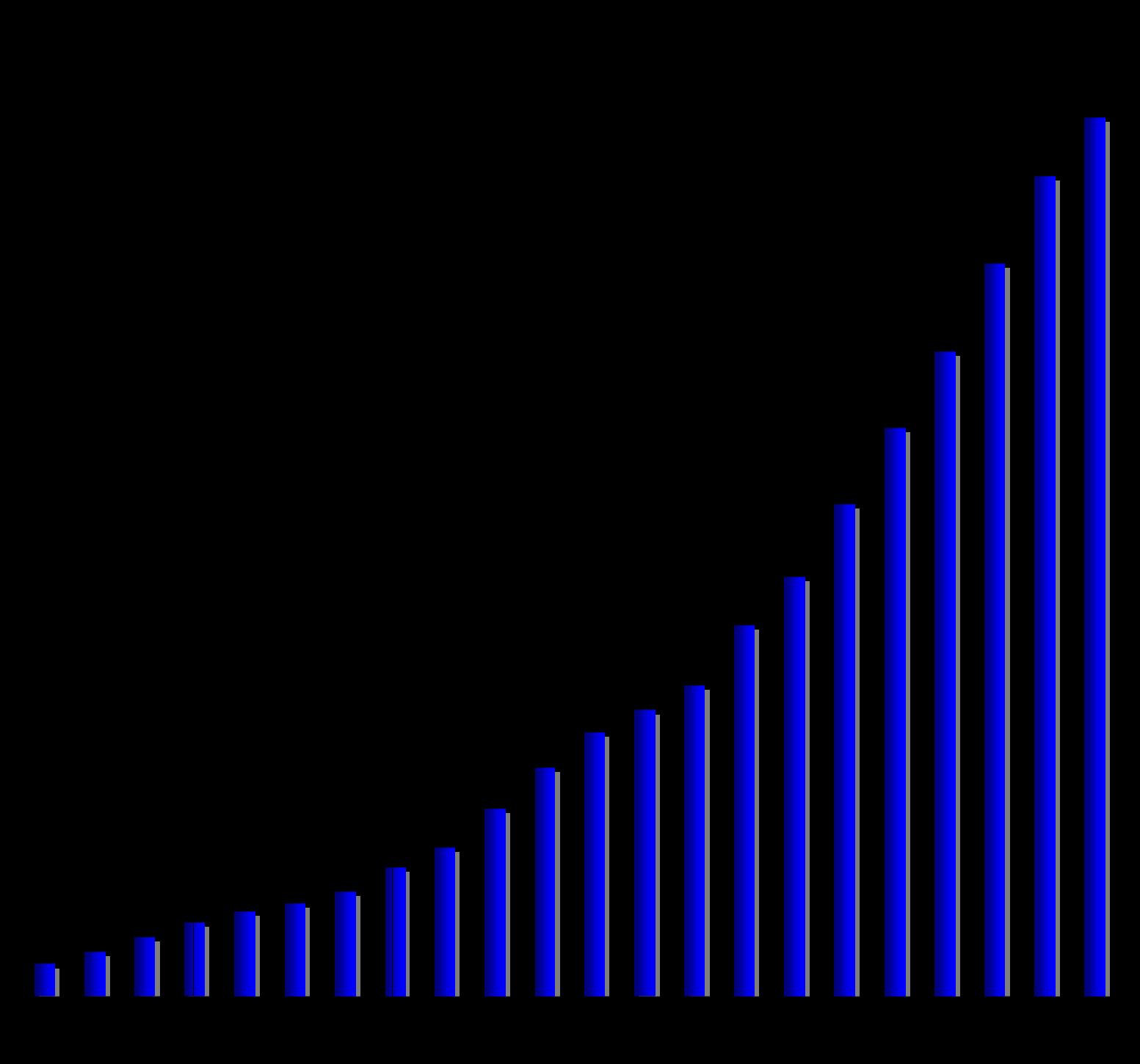

Harley differentiated itself from its Japanese manufacturers by offering support to various enthusiast and social groups. For example, the Harley-Davidson Owners Group (HOG), which was formed in 1983 to encourage Harley-Davidson owners to become more actively involved in the sport of motorcycling, received renewed support and was gradually becoming the industry’s largest company-sponsored motorcycle enthusiast organization. The HOG worldwide membership had grown to 900,000 at the end of 2004 (see Exhibit 1). (In contrast, Honda’s Gold Wing Road Riders Association had 75,000 members.) In highlighting the impact of HOG on the Harley brand, an article in BusinessWeek noted:

[T]he real buzz comes from the 886,000 members of the company-sponsored Harley Owners Group. They are the ones who organize rides, training courses, social events, and charity fund-raisers. They pore through motorcycle magazines and wear the Harley-branded gear to feel more like rugged individualists and outlaws when they take to the road on weekends. A quarter of a million of them descended on Milwaukee last Labor Day to celebrate the brand’s centennial. No wonder more than half of new Harley sales are to current customers who are trading up. The brand is self-reinforcing.[14]

Interest among women riders was (and continued to be) cultivated through “The Ladies of Harley,” a group that aimed to increase interest among young women motorcyclists.

When Teerlink retired in 1997, Jeffrey Bleustein became CEO and a year later added the title of chairman. He continued Harley’s transformation through “new product development, upgraded manufacturing technology, capacity and processes, a modernized and strengthened dealer network, and ‘close to the customer’ marketing—conceived and implemented through employees empowered to operate to their full potential.”[15] Under his leadership, Harley-Davidson’s annual revenues grew from $1.5 billion in 1996 to $5 billion in 2004, and the net income grew from $143 million to $890 million over the same period (see Exhibit 2). In April 2005, Bleustein retired as CEO but agreed to stay on as chairman. James L. Ziemer, who had been with the company for 33 years, was appointed president and CEO. Bleustein pushed Harley “into places it has never gone, creating new generations of hogheads with its first small, cheap bike in more than 20 years and grabbing riders from rival brands and abroad with a radical new motorcycle, the V-Rod, that is Harley’s biggest break from tradition in 65 years.”[16]

Preparing for the Next Century

Despite the company’s record growth and earnings during the last decade, a few analysts began to question whether Harley could maintain such an impressive track record over the next decade. First, analysts following the company were concerned about Harley’s slowing sales in important segments. Noted John Moran, an analyst with Ryan Beck & Co:

Driven by the popularity of the Harley-Davidson brand, heavyweight motorcycle registrations exhibited robust growth from 1996 to 2000. However, growth in the touring and cruising market slowed considerably in the second half of 2002 and throughout 2003 and 2004. The company believes that global demand for heavyweight motorcycles grows at an average core rate of 7% to 9% per year, having averaged 8.6% since 1991. However, we believe that core growth may be somewhat below that figure (5% to 8%). For 2005 we estimate total wholesale shipment growth (excluding Buell units) of just 3.4%. This (slowing) trend suggests that the market for Harley-Davidson’s products may be maturing.[17]

Second, but related to the first, a few analysts were concerned that baby boomers, who formed a majority of Harley’s customer base, were aging. The median age of the Harley customer, which was 35 years in 1987, was now closer to 47 (see Exhibit 3). Reports indicated that over 60% of motorcycle riders were between the ages of 35 and 54. Thus, many were baby boomers born between 1946 and 1964.

According to Donald Brown, a consultant to the industry, the prime age for motorcycle customers was 35 to 44. He noted, “This age group’s numbers began to decline in 1999 and will continue to do so through 2016. Since Harley can’t replace all its boomer customers from a limited pool of boomers, it must reach deeper than before into the youth market. The result . . . it will have to compete more head on with the Japanese.”[18]

Customers who bought Japanese bikes tended to be younger and favor sleek, high-revving sports bikes. For instance, the median age of customers who bought Sukuzi’s sports bikes was 33. Also, sports bikes with smaller engines typically sold for under $10,000, while most Harleys, which were

8

priced higher ($14,000 to $18,000), were beyond the reach of younger riders. Worse, argued marketing consultant Al Ries:

Harley’s close association with boomers could make the brand harder to sell to younger customers when they have cash to splurge. Kids want something different. . . . It’s almost universal that the younger generation rebels against the older generation, whether it’s music, fashion or the toys they buy. . . . The stronger the brand is with the older generation, the weaker it is with the younger generation.[19]

Ries went on to point to Buick in the automotive world and Levi’s in apparel as examples of companies that forged a strong link with an older generation but then had trouble winning over younger customers. Counted Bob Klein, a Harley spokesman:

If you look at our largest buyer group, men in the 35 to 54 age range, that population segment remains essentially constant through at least 2020. . . . There are 41 million U.S. men in the segment currently that actually goes up slightly in 2010, just a tad over 41 million in 2020. So, that group of our largest rider base is basically constant over the next 15 to 20 years. [Moreover] as boomers get older, they’re determined not to age. They lead more active and adventurous lifestyles.[20]

Echoed Moran, the analyst with Ryan Beck & Co:

The oldest of the estimated 80 million Baby Boomers are now entering their late 50s while the youngest Boomers are just entering the earlier part of their 40s. As a generation, Boomers are more affluent and active than any American generation preceding them. . . .We believe that as Boomers age, they are likely to continue riding (indeed, as they retire they may very well ride more). . . . Assuming the company’s demographic target ages somewhat and that Boomers remain active riders into their early 60s . . . Harley-Davidson’s addressable market expands to 107.1 million Americans between the ages of 35 and 64 in 2000. This larger demographic is expected to grow to 122.7 million people in 2010 and to approximately 124.2 million people in 2020 before moderating. This noted, we think it somewhat optimistic to expect Boomers to ride well into their mid/late 60s and 70s, and it will, therefore, become increasingly important for Harley-Davidson to address shifting demographics.[21]

A detailed look at the company’s strategy suggested that it was taking measures to reach younger customers, as well as finding new ways to maintain its growth in its traditional segments.

Buell Acquisition

Since the company did not offer a sports model with a smaller engine, in 1998 it acquired 100% of Buell, in which it held a minority investment. Buell was founded by a former Harley employee, Erik Buell, who left the company to create a line of racing bikes powered by Harley engines mounted on modified Harley frames. The VR-1000 motorcycles that Buell produced had successfully competed on the international racing circuit. Buell motorcycles such as the Blast 500-cc model started at $4,595, but prices for the larger models could reach $10,000. These bikes catered to younger buyers with smaller budgets. In 2004, the company shipped about 9,000 Buell motorcycles to dealers, 60% of which went overseas. About 250 of Harley’s 659 dealers sold Buell motorcycles, and growth in yearto-year sales was slow; in the case of Japan and Australia, sales were declining (see Exhibit 4 for more details).

The V-Rod and New Sportster Line

Inspired by the VR-1000 racing motorcycles, in 2001 Harley-Davidson introduced the V-Rod, the company’s first motorcycle to combine fuel injection, overhead cams, and liquid cooling. The V-Rod represented Harley’s try at high-performance motorcycles. The V-Rod was a 600-pound motorcycle made of chrome and brushed aluminum and cost over $17,000. It boasted 110 horsepower, nearly twice the muscle of a typical hog. Noted Forbes:

It [the V-Rod] was designed to appeal to two audiences Harley has struggled to delight: young, hip Americans who would rather ride a sexy Ducati, and Europeans, who swoon for the Teutonic oomph of BMWs. To get to them, the company teamed up with Porsche to build a liquid-cooled engine. Liquid cooling allows riders to rev a little higher and hotter in each gear, boosting acceleration. It doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it was a giant step for a company so stubbornly conservative that it has made only air-cooled engines for 100 years; its designers just couldn’t bear the idea of hanging a radiator on the front of the bike. The move was such a shock that Motorcyclist put the V-Rod on its October 2001 cover with the headline “Cold Day in Hell.”[22]

However, warned Fortune: “Making changes is tricky for a company with Harley’s cult following: They risk alienating current customers. The V-Rod’s water-cooled engine is a big departure from Harley’s traditional air-cooled one, and to some uneasy riders a portent of additional unwelcome change to come.”[23]

In early 2005, Harley launched a second bike as part of the V-Rod family, which it named the “Street-Rod.” However, a recent article in The New York Times noted, “The V-Rod was intended to give Harley’s a mechanically sophisticated all-American model that would attract riders who might otherwise gravitate to muscle-bound cruisers from Japan and Italy. . . . Fact is, the V-Rod has not been the success Harley had hoped for. Nor has the Street-Rod sizzled since its February (2005) debut.”[24] The company disagreed, noting that 50,000 new motorcycles had been sold since 2001 and this new line had been a fantastic sales success story.

The company also redesigned its sportster family of entry-level, lower-priced bikes in 2004 to appeal to younger riders and women riders. With prices starting at $6,500, the company was attempting to position the new sportster within the grasp of a younger group of riders it hoped would grow loyal to the Harley-Davidson brand. The line also targeted women riders, who now accounted for 10% of total Harley sales in 2004, up from 2% a decade earlier. Noted an analyst’s report:

In terms of marketing, Harley-Davidson continues to target events and media that are of interest to the key constituents in its emerging customer segments. For example, in 2004 the company held two events for leading national women’s media, an event for journalists

10

representing African-American media, and an event for key Hispanic media. The company also hosted its first-ever new motorcycle launch dedicated solely to female motor-journalists and continued its support of various bike rallies focused on minorities.[25]

Further, some Harley enthusiasts were also purchasing the sportster as a second bike. While early sales were brisk, it was too early to tell what the final impact of the redesigned sportster line was likely to be in the long run.

The Rider’s Edge and Rental Programs

In 1999, Harley launched a rental program to hook customers and entice them to buy a Harley. This rental program, offered by 250 dealers, was available in 52 countries such as Italy, Australia, Canada, France, and Mexico. In 1999 the number of days motorcycles were rented was 401, but in 2004 the number was 224,134. Harley claimed that its survey of rental customers showed that 32% bought a bike or placed an order and another 37% planned to buy one within a year. Also, 50% of the renters spent over $100 on accessories.[26] While most analysts following the company believed that this program helped sales, they were unclear about the magnitude of its impact.

In 2000 Harley initiated the Rider’s Edge program through a few participating dealers. This program offered motorcycle-riding lessons that lasted for four days and cost students $350.[27] Noted one analyst’s report: “In 2004, 18,427 people took the Rider’s Edge New Rider Course, up 30% from 2003. Historically, approximately 70% of Rider’s Edge participants purchase a motorcycle within 18 months . . . [and] that approximately 40% of Rider’s Edge participants are women (compared to 10% of total sales) and 30% are under the age of 35 (compared to 15% to 18% of total sales).”[28] However, another report noted: “So far, the program has graduated more than 45,000 [in 2005], but it has yet to revolutionize Harley. In fact, the median age of Harley buyers has increased slightly since the course began. And only 96 of Harley’s 700 or so dealers have agreed to offer the program—in part because of licensing restrictions in some states and the hefty costs of operating the program.”[29]

According to one dealer, it cost him $250,000 to gear up for the Rider’s Edge program. The amount the students paid allowed him only to break even. The real payoff to the dealer was when students bought motorcycles after the training sessions. This dealer noted that he tracked $4.5 million in sales to people who took the course, an average of two bikes per class plus revenues from helmet sales from those who took the course.[30]

Harley Revises Sales Estimates

As noted earlier, at the end of April 2005, the company’s stock price declined 17% in a single day, despite an 11% increase in first-quarter profits and 6% increase in sales. The decline reflected the company’s revised estimates for planned 2005 sales; the company lowered its sales estimate by 10,000 units and noted that it planned to make 329,000 units for the year. It also revised its financial forecast for 2005 by noting that earnings would rise 5% to 8%, down from a previous forecast of about 15%. But it did not change the company’s long-range forecasted sales of 400,000 motorcycles in 2007 and projected annual earnings growth in the mid-teens. Nor did it mention anything about its belief that global demand for heavyweight motorcycles would grow at an average core rate of 7% to 9% per year, having averaged 8.6% since 1991.[31]

A few analysts feared a bike glut and began to question whether: (1) Harley could meet its longrange goal of selling 400,000 motorcycles by 2007 given the slowdown in cruiser segments; (2) it could continue to achieve annual earnings growth in the mid-teens; and (3) it could make greater inroads in attracting younger riders and women riders in the performance segment of the industry

Exhibit 1 The Growth of Harley Owners Group, 1983–2004 (worldwide membership in 000s)

Source: Harley Corporation, membership at the end of the year and 10-K report.

Harley-Davidson: Preparing for the Next Century 906-410

Exhibit 4 Motorcycle Industry Registration Statistics and Harley-Davidson Market Share (units)

1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | |

U.S. and Canada 651+cc Volume | 178,521 | 205,407 | 246,214 | 297,849 | 366,247 | 422,787 | 474,955 | 495,436 | 530,769 |

H-D Volume | 85,063 | 99,298 | 116,110 | 142,042 | 163,984 | 185,571 | 220,143 | 238,243 | 255,795 |

Buell Volume | 1,740 | 1,912 | 3,333 | 4,022 | 4,306 | 2,695 | 3,023 | 3,719 | 3,823 |

HDI Total Volume | 86,803 | 101,210 | 119,443 | 146,064 | 168,290 | 188,266 | 223,166 | 241,962 | 259,618 |

% Change 651+cc Volume | 9.5% | 15.1% | 19.9% | 21.0% | 23.0% | 15.4% | 12.3% | 4.3% |

Step by Step Solution

3.50 Rating (147 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

HarleyDavidson has maintained its strong presence in the global motorcycle industry over time The companys name HARLEY DAVIDSON was derived from its founders Arthur Walter Davidson and William Harley ... View full answer

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Document Format (1 attachment)

6555ec43c8ed2_545886.docx

120 KBs Word File