Hirschheim and Klein's (1989) paper describes the four paradigms. Please help to answer the following questions based on the readings attatched below. The reading is a functionalist in nature.

What is the argument presented by the author?

What is the method - how do the author(s) convince their readers?

Analyse the assumptions made in the paper.

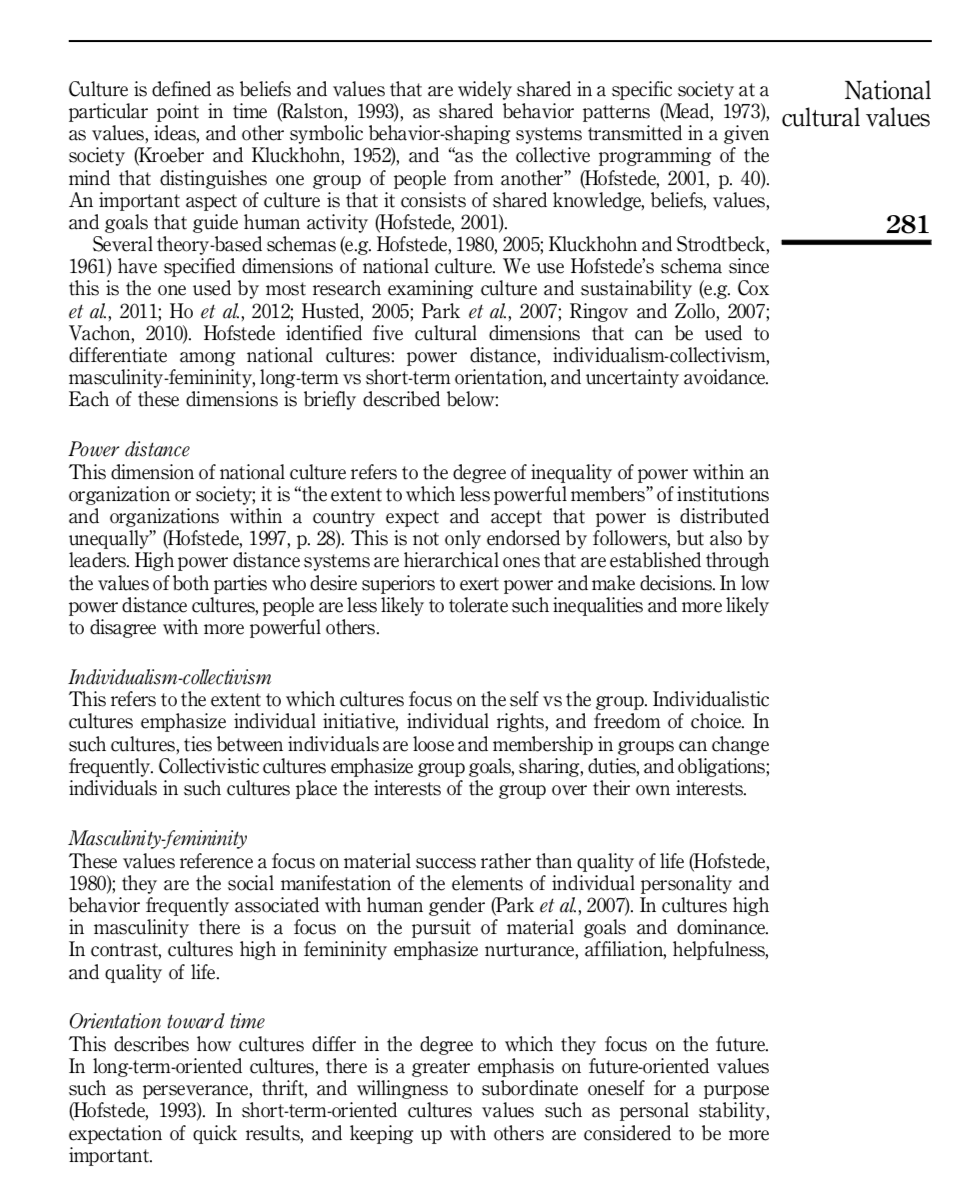

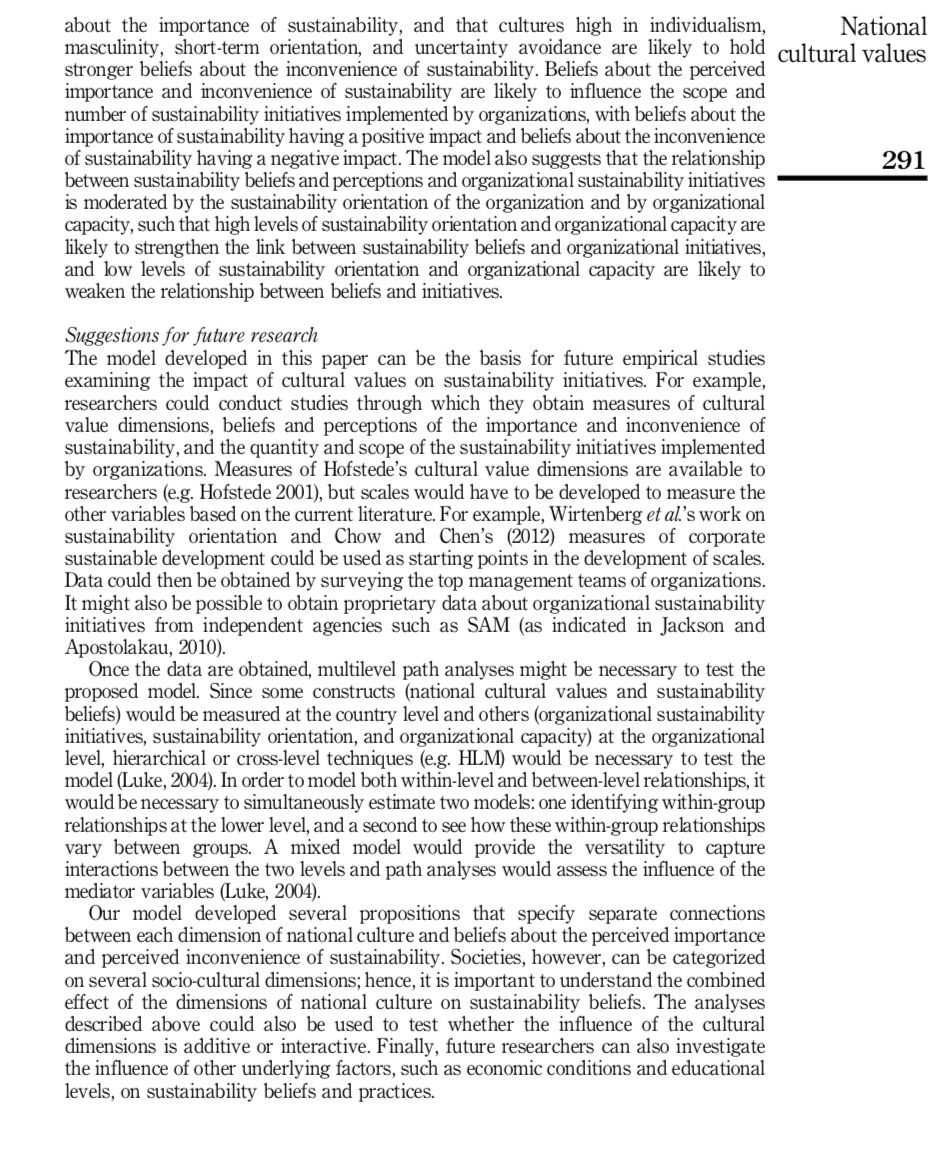

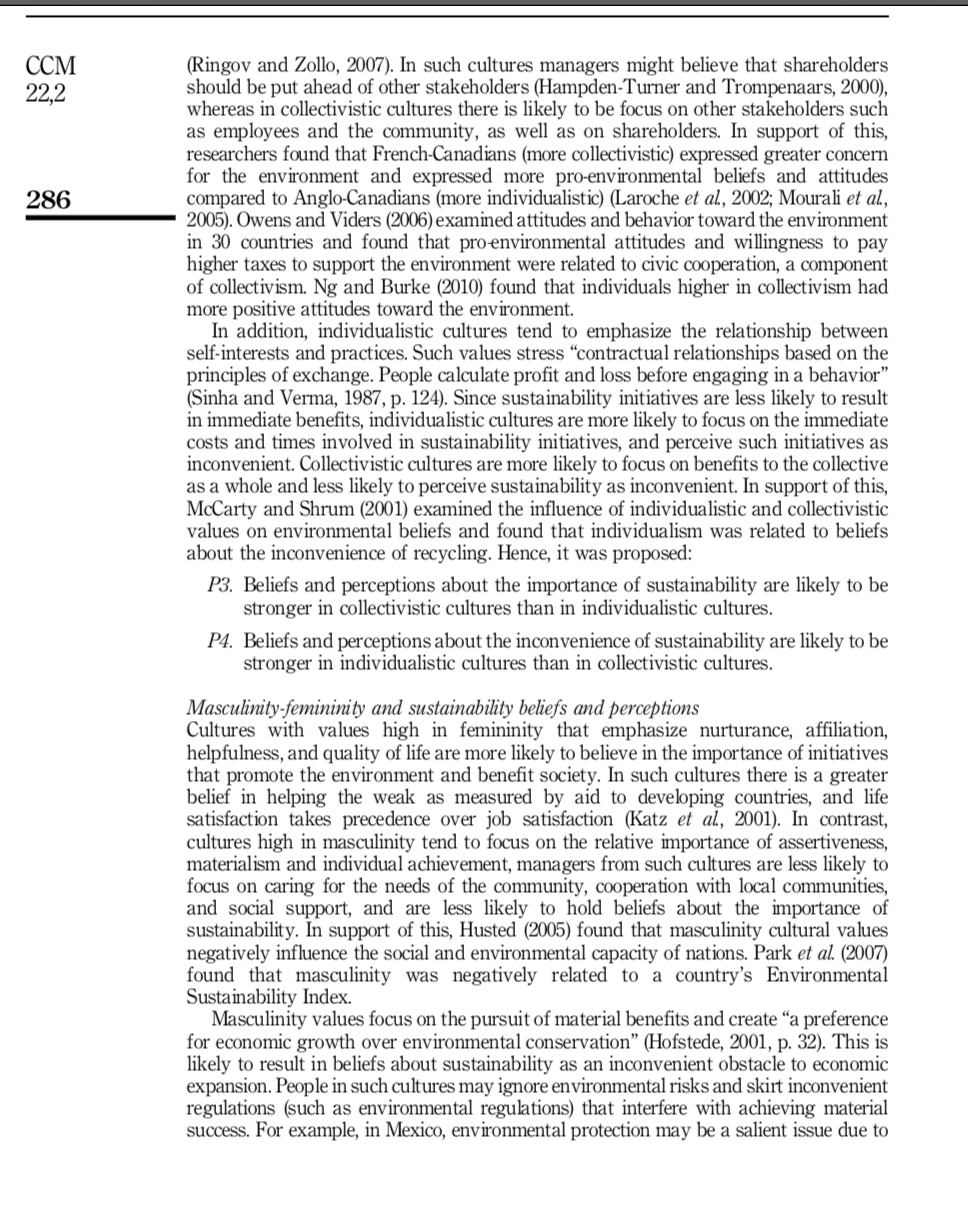

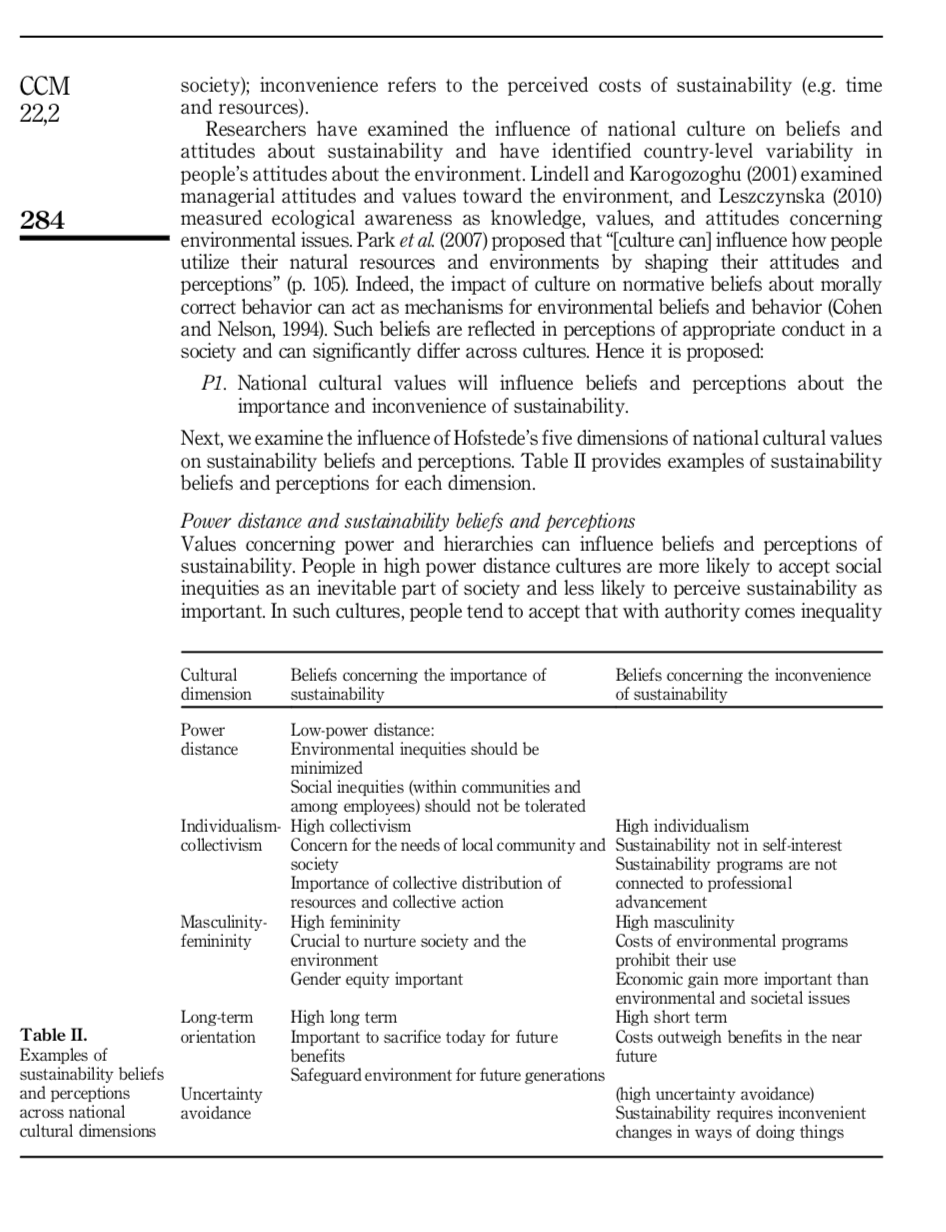

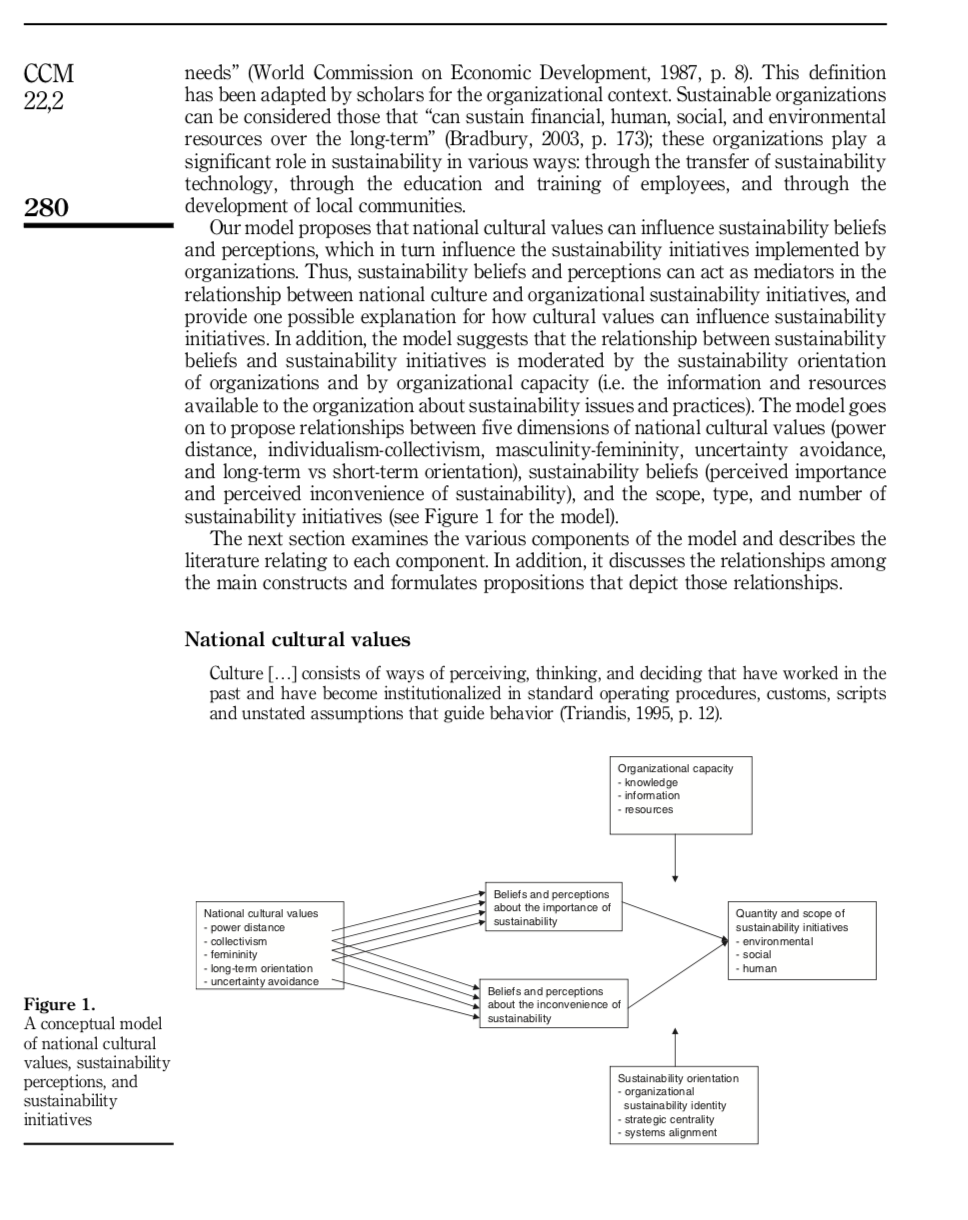

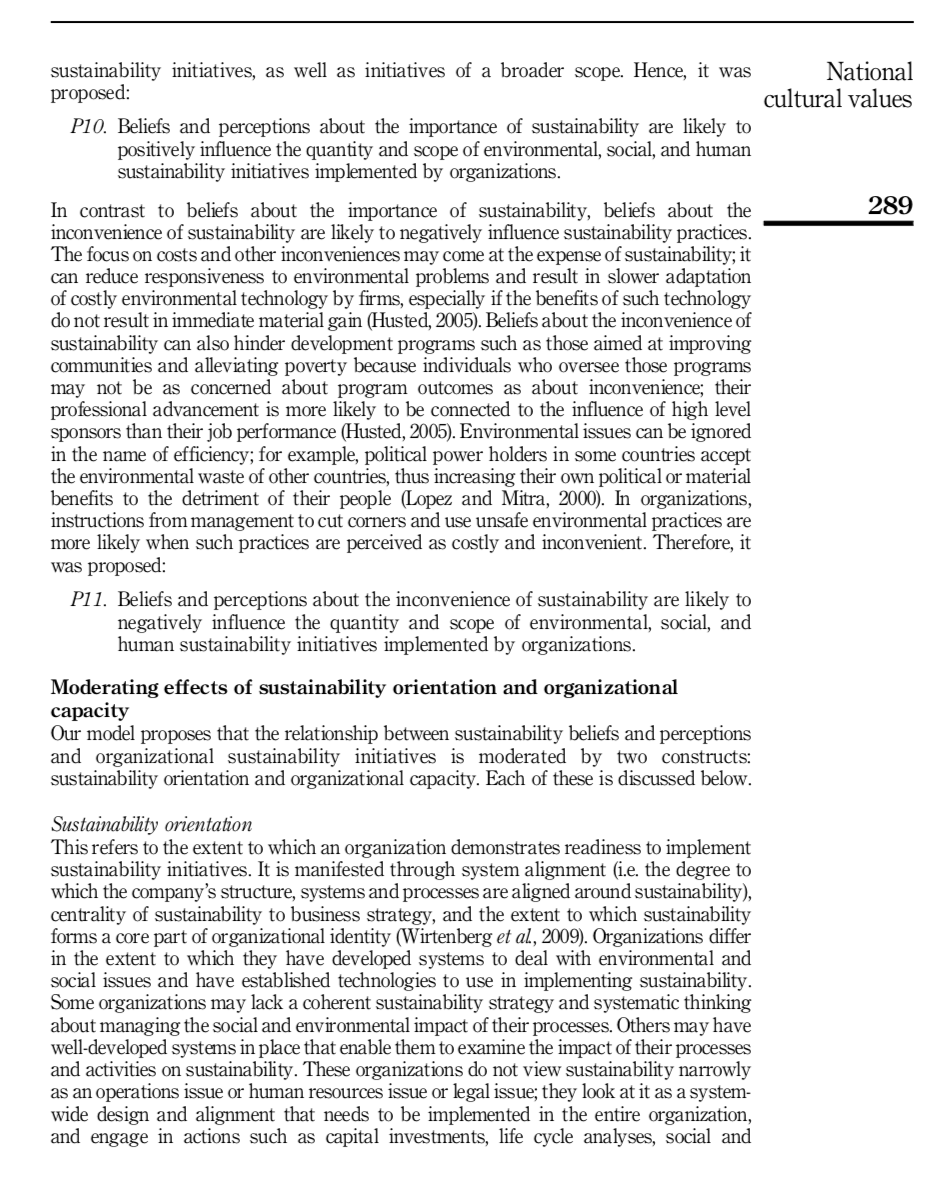

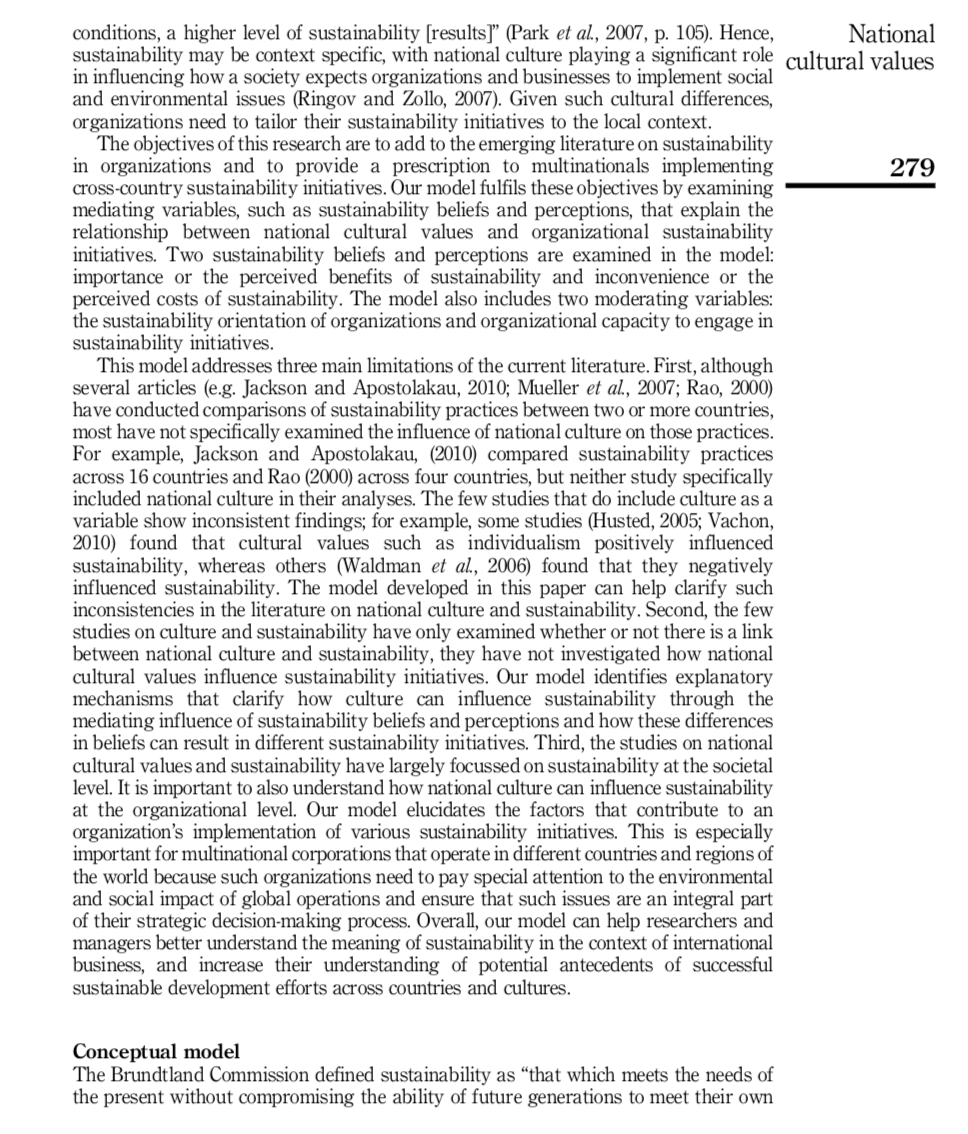

and are more willing to put up with inequality (William and Zinkin. 2MB}. Power distance values indicate that those in positions of power are. by their very position1 more equal than others and thus entitled to unique privileges according to their rank and status (Waldman at at. 2005). High power distance societies are likely to be \"prone to the manipulative use of power. a lack of equal opportunities for minorities and women. a lack of personal or professional development within the organization" (Waldman at at, 2006, p. 835}. These values are likely to result in high level managers in position of power who lack concern for the communities in which they operate (Carl at of. 3004) as well as the welfare of employees. and are less likely to perceive sustainability as an important issue. Societies with high power distance are more likely to accept poor working conditions which can lead to social inequity in organizations (Scholtens and Dam, 2007). Such societies are characterized by organizations that are highly structured and hierarchical, with organizational decisions based on favoritism and loyalty rather than merit. Therefore such cultures are less likely to perceive human rights or employee equity as important. Katz at a}. (2W1) argued that \"a higher level of power distance suggests less concern about the environment than the opposing case Historically. cultures with higher levels of power distance have not emphasized human intervention in the natural environment" (p. 158). Hence1 the respect for authority embedded in high power distance cultures can result in less capacity for debate and weaker business responses to environmental and social problems (Katz at at. 2001}. as opposed to low power distance cultures. In support of this, empirical research has found that societies with higher levels of power distance present a greater degree of acceptance of polluted environments. Power distance has also been negatively linked to environmental performance as measured by the Environmental Sustainability Index developed by the World Economic Forum (Cox at of, 2011; Husted1 21135; Park at of, 2W7). Similarly, Vachon {2010} found that higher power distance was linked to fewer corporate environmental practices. In contrast, in low power distance cultures social and human sustainability initiatives are more likely to be openly discussed and perceived as important. Such cultures stress egalitarianism and put social pressure on managers to minimize inequities1 whether in terms of society or the environment. In such cultures sustainability is more likely to be perceived as important. Therefore1 it was proposed: P2. Beliefs and perceptions about the importance of sustainability are likely to be stronger in low power distance cultures than in high power distance cultures. Indidualsm-coecm'sm and sustainabity b35213 and perceptions The relationship between individualism-collectivism and sustainability beliefs and practices is a complex one Managing the environment for sustainability is a collective enterprise in which benefits to the collective should outweigh costs to the few. Collectivists. who place the interests of the group first, are more likely to believe in the importance of sustainability. Collectivists' beliefs and attitudes promote a willingness to share scarce resources. support what is best for society as a whole and are more consistent with protection of the environment and development of society {McCarty and Shrum. 3131). Thus, individuals in collectivistic cultures are more likely to perceive sustainability as an important goal for society. In contrast, the self-interest emphasis in individualistic cultures is less likely to be consistent with beliefs that support sustainability. Managers from individualistic cultures are less likely to demonstrate concern about the impact of their firm on society National cultural values CCM 222 found that uncertainty avoidance was negatively linked to environmental. human. and social sustainability. We posit that these mixed ndings may be due to differences in the perceived inconvenience of sustainability in high and low uncertainty avoidance cultures. Perhaps managers from high uncertainty avoidance cultures examine the risks inherent in either implementing or not implementing sustainability initiatives and implement sustainability programs based on their sustainability beliefs. Thus. it was proposed: P9. Beliefs and perceptions about the inconvenience of sustainability are likely to be stronger in high uncertainty avoidance cultures than in low uncertainty avoidance cultures. The inuence of sustainability beliefs and perceptions on organizational sustainability initiatives Sustainability beliefs and perceptions, in turn. inuence how people in different cultures interpret the meaning of sustainability and implement those practices. Hence. national cultural values can inuence organizational sustainability initiatives through the mediating inuence of beliefs and perceptions about the importance and inconvenience of sustainability. Next. we discuss three categories of sustainability initiatives (environmental. social. and human) which can be inuenced by beliefs and perceptions. Environmental sustainability includes corporate environmental management. It emphasizes operating within the carrying capacity of the ecosystem by reducing environmental pollution. resource consumption. and the ecological footprint (Lindgreen emf. 21339}. and consists ofpracticesengagedinby an organizationthatminimizeitsharm to the land. water. and air. Organizations may reduce the risk of environmental accidents by training employees on processes. and engage in monitoring the environmental impact of products. services and processes. or they can develop new. alternate processes that reduce waste and emissions by using nm-traditional materials (Lindgreen at at. 2009: Chow and Chen. 2012). Social sustainability can be thought of as enhancing social welfare and promoting healthier societies. This domain of sustainability consists of reducing social inequalities and improving quality of life; it includes a concern for the common good It consists of practices that improve the health and safety of communities. and focus on social impact and human rights (Bansal. 2005). Human sustainability has been identied as a separate domain by a few scholars. This refers to how organizational processes inuence the physical and mental well-being of organizational members. Pfeffer (2010) argued that \"the health status of the workforce is a particularly relevant indicator of human sustainability and well- being because there is evidence that many organizational decisions about how they reward and manage their employees have profound effects on human health and mortality" (p. 36}. Human sustainability consists of practices such as working conditions. working hours. and the provision of benets such as health insurance (Pfeffer. 2010). Beliefs and perceptions about sustainability inuence the propensity to engage in sustainability behaviors. Hence. beliefs about the importance of sustainability are likely to result in a higher level of implementation of environmental. social. and human sustainability initiatives that safeguard the environment for the future and help local communities. Such organizations are more likely to implement a larger number of CCM Implications for practice 22,2 Our model suggests that business practices need to be aligned with prevailing cultural norms. Managers should anticipate and minimize potential conflicts arising because of cultural differences, and multinational organizations can adapt their approaches to sustainability based on host country expectations. Since multinational corporations operate in different countries, they engage in relations with partners, suppliers, and 292 distributors in those countries. These relationships, however, are not without conflict. Multinationals and their partners may have conflicting ideas about various issues, including sustainability initiatives and programs. These conflicts and differences often arise due to cultural incongruence. Because of differing cultural backgrounds, people may perceive and evaluate the world differently, and react to sustainability issues in a manner that is often incomprehensible to those from another culture. Hence, the cultural background of business partners, suppliers, and consumers will influence their sustainability beliefs and their evaluation of the sustainability initiatives engaged in by the organization. Therefore, it is important to identify and understand the influence of cultural values on sustainability beliefs as well as the effectiveness of sustainability initiatives. A multinational operating in a country with strong beliefs about the inconvenience of sustainability will have to behave in a manner that does not jeopardize its reputation and formulate appropriate sustainability strategies that allow the company to conduct its operations in a manner acceptable to the host country, as well as its global stakeholders. The same multinational, when operating in a country with strong beliefs about the importance of sustainability will have to recognize that standards for environmental, social, and human sustainability are well recognized and respect them. Hence, the ability of multinationals to implement global sustainability programs and standards depends on cultural values, and it is important for managers, especially those in multinationals, to understand how national culture can influence sustainability in different countries. International aid agencies have been plowing vast resources in order to ensure better environmental, social and human outcomes in developing countries. As they venture into new projects, the aid agencies need to be cognizant of local beliefs and perceptions of the importance and inconvenience of sustainability. These agencies will need to rely on local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to delivery environment, social, and human services. However, the international aid agencies will have to assess the local NGOs' capacity (knowledge, information, resources) to effectively deliver the proposed services. In addition, they need to assess the NGOs' organizational identity, strategic centrality, and systems alignment toward sustainability. Since many NGOs in the developing world might lack such sophistication, international development agencies might need to first invest in training programs to help local NGOs build their organizational capacity and have the proper sustainability orientation. Implications for policy As countries enter into free-trade pacts, sustainability is often a core issue of contention among the different countries, reflecting the variance in culture and hence beliefs and perceptions of the importance and inconvenience of sustainability. Since sustainability policies and programs are most likely to be effective if they are tailored to the national culture, it may be necessary for free-trade agreements to allow a degree of flexibility in allowing countries to adapt sustainability initiatives to the appropriate cultural context. For example, sustainability education programs in collectivist countries could be allowed toUnceamty avoidance This dimension of national culture is dened as the \"extent to which members of a culture feel threatened by uncertainty and unknown situations\" (Hofstede, 1997, p. 113): it refers to the degree to which a culture tolerates ambiguity and situational demands. In high uncertainty avoidance cultures people prefer to avoid ambiguous situations and feel uncomfortable without the structure of rules and regulations; low uncertainty avoidance cultures reflect openness to change and propensity to take risks. Researchers have examined country-level differences in aspects of sustainability such as environmental innovation. environmental management. social involvement. and fair labor practices. For example. Rao (2000) found differences in environmental management systems between the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia. and Thailand, and Jackson and Apostolakau (2010} found differences in environmental and social sustainability practices across 16 countries. In contrast. Lindell and Karagozoghu (2001) found no differences in the degree of environmental orientation between the USA and Nordic countries. and Mueller at of. (2007) found no signicant differences in sustainability practices between German and New Zealand companies. Other researchers have investigated country-level variability in people's attitudes about the environment and conservation For example, Kellert (1996} found that people in Japan were less interested in ecological processes and wildlife conservation. whereas those in Germany were more interested in the protection of wildlife. The research discussed above, however. did not measure cultural values nor did it connect sustainability practices to national culture. A few scholars have examined the relationship between national cultural values and sustainability. The results of these studies. however, show inconsistent findings (see Table I for a summary). For example, Husted (2005} measured social and institutional capacity for environmental sustainability with gross national product per capita (GNPC) and population growth as control variables. He found individualism. masculinity and power distance to be related to institutional capacity and concluded that \"egalitarianism. individualism and feminine values appear to constitute \"green" or \"sustainable\" values\" (p. 356). Park at at (2007) examined the inuence of culture on the relationship between GNPC and environmental sustainability. They found that cultures high in femininity and low in power distance had higher levels of environmental sustainability. but did not nd any influence of individualism Similarly, Cox er a1 (2011) found a relationship between power distance and the interaction of gross domestic product per capita (GDPC) and environmental sustainability. and but did not identify any relationships with uncertainty avoidance or masculinity. As indicated in Table I. the current literature does not provide a clear picture of how national cultural values inuence sustainability practices. For example, Husted (2W5) and Vachon (2010} found a positive relationship between individualistic values and sustainability, whereas Waldman at of (2006} found a negative relationship. Further. Park at of. (2037} and Ringov and Zollo (2007} found no significant relationship between individualism and sustainability. Similarly. Ho at of (2012) found a positive relationship between masculinity cultural values and environmental sustainability. whereas Park at at (2007) and Ringov and Zollo (2007) found a negative relationship; Vachon (2010} found no signicant relationship. We suggest that these inconsistent findings might be better understood by examining how national cultural values inuence sustainability initiatives through the mechanism of sustainability beliefs and perceptions. Culture is dened as beliefs and values that are widely shared in a specic society at a National particular point in time (Ralston. 1993}. as shared behavior patterns (Mead. 1973). cultural values as values. ideas. and other symbolic behavior-shaping systems transmitted in a given society {Kroeber and Kluckhohn. 1952}. and \"as the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes one group of people from another\" [l-Iofstede. 2001. p. 40). An important aspect of culture is that it consists of shared knowledge beliefs. values. and goals that guide human activity (l-[ofstede. 20m). 281 Several theory-based schemas [e.g. Hofstede. 1980. 2005; Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck. 1961} have specied dimensions of national culture. We use Hofstede's schema since this is the one used by most research examining culture and sustainability (e.g. Cox et all. 2011; H0 at all. 2012; Husted. 2005: Park at all. 2807; Ringov and Zollo. 2337; Vachon. 2010}. Hofstede identied five cultural dimensions that can be used to differentiate among national cultures: power distance. individualism-colledivisnL masculinity-femininity. long-term vs short-term orientation. and uncertainty avoidance. Each of these dimensions is briey described below: Power dt'stmce This dimension of national culture refers to the degree of inequality of power within an organization or society: it is \"the extent to which less powerful members" of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally\" {I-Iofstede. 1997. p. 28). This is not only endorsed by followers. but also by leaders. High power distance systems are hierarchical ones that are established through the values of both parties who desire superiors to exert power and make decisions. In low power distance cultures. people are less likely to tolerate such inequalities and more likely to disagree with more powerful others. Individuasmcoecvism This refers to the extent to which cultures focus on the self vs the group. Individualistic cultures emphasize individual initiative, individual rights. and freedom of choice. In such cultures. ties between individuals are loose and membership in groups can change frequently. Collectivistic cultures emphasize group goals. sharing. duties. and obligations; individuals in such cultures place the interests of the group over their own interests. Masmrdwfmimnib' These values reference a focus on material success rather than quality of life [Hofstede. 1980): they are the social manifestation of the elements of individual personality and behavior frequently associated with human gender (Park at all. 2007}. In cultures high in masculinity there is a focus on the pursuit of material goals and dominance. In contrast. cultures high in femininity emphasize nurturance. afliation. helpfulness. and quality of life. Orimtation toward time This describes how cultures differ in the degree to which they focus on the future. In long-term-oriented cultures. there is a greater emphasis on futurecriented values such as perseverance. thrift. and willingness to subordinate oneself for a purpose (Hofstede. 1993). In short-term-criented cultures values such as personal stability. expectation of quick results. and keeping up with others are considered to be more important. about the importance of sustainability. and that cultures high in individualism. masculinity. short -term orientation. and uncertainty avoidance are likely to hold stronger beliefs about the inconvenience of sustainability. Beliefs about the perceived importance and inconvenience of sustainability are likely to inuence the scope and number of sustainability initiatives implemented by organizations. with beliefs about the importance of sustainability having a positive impact and beliefs about the inconvenience of sustainability having a negative impact. The model aho suggtts that the relationship between sustainability beliefs and perceptions and organizational sustainability initiatives is moderated by the sustainability orientation of the organization and by organizational capacity. such that high levels of sustainability orientation and organizational capacity are likely to strengthen the link between sustainability beliefs and organizational initiatives. and low levels of sustainability orientation and organizational capacity are likely to weaken the relationship between beliefs and initiatives. Suggestions for tture research The model developed in this paper can be the basis for future empirical studies examining the impact of cultural values on sustainability initiatives. For example. researchers could conduct studies through which they obtain measures of cultural value dimensions. beliefs and perceptions of the importance and inconvenience of sustainability. and the quantity and scope of the sustainability initiatives implemented by organizations. Measures of Hofstede's cultural value dimensions are available to researchers (e.g. Hofstede 2001}. but scales would have to be developed to measure the other variables based on the current literature. For example. Wirtenberg et (11's work on sustainability orientation and Chow and Chen's (2012) measures of corporate sustainable development could be used as starting points in the development of scales. Data could then be obtained by surveying the top management teams of organizations. It might also be possible to obtain proprietary data about organizational sustainability initiatives from independent agencies such as SAM (as indicated in Jackson and Apostolakau. 2010}. Once the data are obtained multilevel path analyses might be necessary to test the proposed model. Since some constructs (national cultural values and sustainability beliefs} would be measured at the country level and others (organizational sustainability initiatives. sustainability orientation. and organizational capacity) at the organizational level. hierarchical or cross-level techniques (e.g. HLM) would be necessary to test the model (Luke. 2W4}. In order to model both within-level and between-level relationships. it would be necessary to simultaneously estimate two modeh: one identifying within-group relationships at the lower level. and a second to see how these within-group relationships vary between groups. A mixed model would provide the versatility to capture interactions between the two levels and path analyses would assess the inuence of the mediator variables (Luke. 2004). Our model developed several propositions that specify separate connections between each dimension of national culture and beliefs about the perceived importance and perceived inconvenience of sustainability. Societies. however. can be categorized on several socio-cultural dimensions; hence. it is important to understand the combined effect of the dimensions of national culture on sustainability beliefs. The analyses described above could also be used to test whether the inuence of the cultural dimensions is additive or interactive. Finally. future researchers can also investigate the inuence of other underlying factors. such as economic conditions and educational levels. on sustainability beliefs and practices. National cultural values 291 CCM 22.2 (Ringov and Zollo. 2307}. In such cultures managers might believe that shareholders should be put ahead of other stakeholders (Hampden-Turner and Trompenaars. 2030). whereas in collectivistic cultures there is likely to be focus on other stakeholders such as employees and the community. as well as on shareholders. In support of this. researchers found that French-Canad'ans (more collectivistic) expressed greater concern for the environment and expressed more pro-environmental beliefs and attitudes compared to Anglo-Canadians (more individualistic) I[Laroche at of. 2002.- Mourali at of. 2005). Owens and Viders (23%) examined attitudes and behavior toward the environment in 30 countries and found that proenvironmental attitudes and willingness to pay higher taxes to support the environment were related to civic cooperation. a component of collectivism Ng and Burke (2)10) found that individuals higher in collectivism had more positive attitudes toward the environment. In addition. individualistic cultures tend to emphasize the relationship between self-interests and practices. Such values stress \"contractual relationships based on the principles of exchange. People calculate prot and loss before engaging in a behavior" (Sinha and Verma. 1987. p. 124). Since sustainability initiatives are less likely to result in immediate benets. individualistic cultures are more likely to focus on the immediate costs and times involved in sustainability initiatives. and perceive such initiatives as inconvenient. Collectivistic cultures are more likely to focus on benets to the collective as a whole and less likely to perceive sustainability as inconvenient. In support of this. McCarty and Shrum (2001} examined the influence of individualistic and collectivistic values on environmental beliefs and found that individualism was related to beliefs about the inconvenience of recycling. Hence. it was proposed: P3. Beliefs and perceptions about the importance of sustainability are likely to be stronger in collectivistic cultures than in individualistic cultures. P4. Beliefs and perceptions about the inconvenience of sustainability are likely to be stronger in individualistic cultures than in collectivistic cultures. Moscum'tyfemininity and sustainability beliefs and perceptions Cultures with values high in femininity that emphasize nurturance1 afliation. helpfulness. and quality of life are more likely to believe in the importance of initiatives that promote the environment and benet society. In such cultures there is a greater belief in helping the weak as measured by aid to developing countries. and life satisfaction takes precedence over job satisfaction (Katz at of. 2301). In contrast. cultures high in masculinity tend to focus on the relative importance of assertiveness. materialism and individual achievement. managers from such cultures are less likely to focus on {raring for the needs of the community. cooperation with local communities. and social support. and are less likely to hold beliefs about the importance of sustainability. In support of this. Husted (M) found that masculinity cultural values negatively influence the social and environmental capacity of nations. Park at a}. (3)07) found that masculinity was negatively related to a country's Environmental Sustainability Index. Masculinity values focus on the pursuit of material benets and create \"a preference for economic growth over environmental conservation\" (l-Iofstede1 ZJOI. p. 32). This is likely to result in beliefs about sustainability as an inconvenient obstacle to economic expansion. People in such cultures may ignore environmental risks and skirt inconvenient regulations (such as environmental regulations) that interfere with achieving material success. For example. in Mexico. environmental protection may be a salient issue due to CCM society); inconvenience refers to the perceived costs of sustainability (e.g. time 22,2 and resources). Researchers have examined the influence of national culture on beliefs and attitudes about sustainability and have identified country-level variability in people's attitudes about the environment. Lindell and Karogozoghu (2001) examined managerial attitudes and values toward the environment, and Leszczynska (2010) 284 measured ecological awareness as knowledge, values, and attitudes concerning environmental issues. Park et al. (2007) proposed that "[culture can] influence how people utilize their natural resources and environments by shaping their attitudes and perceptions" (p. 105). Indeed, the impact of culture on normative beliefs about morally correct behavior can act as mechanisms for environmental beliefs and behavior (Cohen and Nelson, 1994). Such beliefs are reflected in perceptions of appropriate conduct in a society and can significantly differ across cultures. Hence it is proposed: P1. National cultural values will influence beliefs and perceptions about the importance and inconvenience of sustainability. Next, we examine the influence of Hofstede's five dimensions of national cultural values on sustainability beliefs and perceptions. Table II provides examples of sustainability beliefs and perceptions for each dimension. Power distance and sustainability beliefs and perceptions Values concerning power and hierarchies can influence beliefs and perceptions of sustainability. People in high power distance cultures are more likely to accept social inequities as an inevitable part of society and less likely to perceive sustainability as important. In such cultures, people tend to accept that with authority comes inequality Cultural Beliefs concerning the importance of Beliefs concerning the inconvenience dimension sustainability of sustainability Power Low-power distance: distance Environmental inequities should be minimized Social inequities (within communities and among employees) should not be tolerated Individualism- High collectivism High individualism collectivism Concern for the needs of local community and Sustainability not in self-interest society Sustainability programs are not Importance of collective distribution of connected to professional resources and collective action advancement Masculinity- High femininity High masculinity femininity Crucial to nurture society and the Costs of environmental programs environment prohibit their use Gender equity important Economic gain more important than environmental and societal issues Long-term High long term High short term Table II. orientation Important to sacrifice today for future Costs outweigh benefits in the near Examples of benefits future sustainability beliefs Safeguard environment for future generations and perceptions Uncertainty (high uncertainty avoidance) across national avoidance Sustainability requires inconvenient cultural dimensions changes in ways of doing thingsNational Power Uncertainty Long-term Authors Sustainability issues measured distance Individualism Masculinity avoidance orientation cultural values Cox et al. Environmental Sustainability ns ns ns (2011) Index x Gross domestic product per capita Ho et al. Intangible value asset - + + + 283 (2012) environmental Intangible value asset - human/social Husted Societal and institutional capacity + ns (2005) for environmental sustainability Parboteeah Environmental behavioral ns et al. (2012) intentions from World Values Survey Park et al. Environmental Sustainability Index ns - ns (2007 Ringov and Intangible value asset - ns I ns Zollo (2007) environmental and human/social Vachon Green corporatism + ns (2010) Environmental innovation ns ns IIII Fair labor practices ns ns Social involvement + ns Waldman Importance in decision making et al. (2006) assigned to environment and employee well-being Importance in decision making Table I. assigned to welfare of community Summary of findings Notes: -, Significant negative relationship; +, significant positive relationship; ns, no significant relationship in the literature The influence of national cultural values on sustainability beliefs and perceptions The values inherent in national cultural systems can influence beliefs and perceptions, and provide guidelines as to what constitutes acceptable and unacceptable behavior and practice (Rokeach, 1973). Values are broad based, whereas beliefs, attitudes and perceptions are oriented toward specific objects and situations (Ajzen, 1991). Behaviors can be considered manifestations of values and attitudes. The literature suggests that specific beliefs and attitudes often mediate the relationship between values and behavior (Alwitt and Ritts, 1996). Thus, national cultural values held by members of a society can influence more beliefs specific to the functioning of organizations (Waldman et al., 2006). National culture consists of fundamental values that people have about the world around them. These influence the formation of their beliefs and perceptions about sustainability, along with their propensity to engage in sustainable behavior and practices. Broad constructs such as national cultural values are unlikely to directly influence organizational sustainability practices; rather, national culture is more likely to affect specific constructs such as beliefs and attitudes, which in turn influence behavior and practices (Mccarty and Shrum, 2001). Similar to Mccarty and Shrum, we propose that two sustainability beliefs and perceptions (importance and inconvenience) will act as mediators of the relationship between national cultural values and sustainability initiatives. Importance refers to the perceived benefits of engaging in sustainability initiatives (e.g. long-term benefits to the environment andportray environmental degradation as a threat to the interests of the collective whole as well National as to family and the close community. Social conformation is important is such cultures, cultural values therefore environmental and social sustainability programs may need to be presented as socially-accepted and normative practices. In high power distance cultures, sustainability may need to be connected to the interests of those in power such as business leaders, whereas in high masculinity societies sustainability will have to be linked to material gain and economic prosperity. After all, sustainability initiatives are successful only to "the 293 extent that they can be integrated into the local cognition" (Ho et al, 2012, p. 437). Conclusion As multinationals attempt to implement sustainability initiatives across countries and cultures, they lack a prescriptive model to tap from the literature. The current literature does not present a clear picture of the relationship between national culture and organizational sustainability. Most studies have not yet investigated the specific impact of culture on sustainability practices, nor have they identified mechanisms that can explain how national cultural values influence sustainability initiatives. Our research bridges this gap in the literature by developing a conceptual model that explains the relationships between national culture and organizational sustainability initiatives through the mediating influence of sustainability beliefs and perceptions. In addition, the influence of organizational capacity and sustainability orientation is included in the model. The model adds to the emerging literature on sustainability and culture, helps researchers and organizations understand how socio-cultural values can impact sustainability, and guides multinationals in the implementation of their sustainability initiatives across the world.the number of multinationals, but economic issues often take priority (Katz et at, 2001}, perhaps because of high masculinity cultural values. Thus, it was proposed; P5. Beliefs and perceptions about the importance of sustainability are likely to be stronger in cultures high in femininity than in cultures high in masculinity. P6. Beliefs and perceptions about the inconvenience of sustainability are likely to be stronger in cultures high in masculinity than in cultures high in femininity. long-tom as short-term orientation mid sustainabiaity been and perceptions In long-term-oriented cultures, managers believe in the importance of making sacrices that bring in future benets to the organization and to society: in short-term cultures managers may be more likely to believe in the here and now and focus on immediate returns, even at the expense of future gains. Sustainability, by its very denition, is inherently long-term oriented, and managers in such cultures are more likely to believe in giving up immediate benefits so as to achieve environmental protection for the benet of future generations. Societies with high long-term orientations also value long- term commitment and respect for tradition, and believe in the importance of future benets over immediate gratification In such cultures, greater attention is paid to developing employees and communities, building relationships, and maintaining bonds. Hence, such cultures are likely to hold beliefs about the importance of social and environmental sustainability. In contrast, short-term-oriented cultures may underscore short-term gratication and immediate returns on time and effort. People in such cultures are likely to prefer immediate economic gains at the expense of future environmental benets. Since the costs of sustainability are more likely to be immediate, and the benets may not be realized until well into the future, short-term-oriented cultures, with their focus on the here and now, are likely to hold beliefs about the inconvenience of sustainability. Therefore, it was proposed; PZ Beliefs and perceptions about the importance of sustainability are likely to be stronger in long-term-oriented cultures than in short-term-oriented cultures. P8. Beliefs and perceptions about the inconvenience of sustainability are likely to be stronger in short-term-oriented cultures than in long-term-oriented cultures. Lhoertointy avoidance and amatoinobititj.l beiiefs and perceptions High uncertainty avoidance cultures are likely to desire predictability which can result in less likelihood of deviating from societal norms and a greater likelihood of conforming to those norms. Such cultures are likely to have organizational barriers to innovation (Ringov and Zollo, 2007}. Since sustainability is likely to result in significant changes to organizational procedures, the thought of implementing sustainability may bring to mind the large number of inconveniences associated with new ways of doing things and changes in protocol. Hence, sustainability is likely to be perceived as risky, costly, and inconvenient in high uncertainty avoidance cultures. Empirical studies examining sustainability in the context of uncertainty avoidance show mixed results. Some have found no signicant link between uncertainty avoidance and environmental activities (Hewett et at, 2006; Husted, 2005; Park et at, 2007}. Other studies have found a few signicant results: for example, Scholtens and Dams, (2007} determined that uncertainty avoidance was positively linked to human rights practices but negatively linked to environmental innovation, and Vachon (2010} National cultural values 287 CCM environmental audits, employee training, labor practices, community outreach, supplier 22,2 certifications, public reporting, and risk management (Epstein, 2008). An organization's sustainability orientation is also manifested through the extent to which sustainability is a core part of its identity. Organizational identity involves facets that describe the enduring characteristics of an organization (Albert and Whetten, 1985) and plays an important role in the success of the organization. For some organizations, 290 sustainability is a core characteristic of organizational identity and consists of key facets of environmental, social, and human sustainability. Because sustainability orientation can influence the ways in which sustainability issues and actions within organizations are defined and interpreted, this can constrain or motivate organizational actions and decision-making processes. Thus, a strong sustainability orientation, as manifested through organizational systems alignment, and the centrality of sustainability to organizational strategy and identity, can enhance the influence of the importance of sustainability on organizational sustainability initiatives. Similarly, a weak sustainability orientation can attenuate this relationship. Therefore, it was proposed: P12. Sustainability orientation is likely to moderate the relationship between beliefs and perceptions about the importance and inconvenience of sustainability and the quantity and scope of environmental, social, and human sustainability initiatives implemented by organizations. Organizational capacity Organizations also differ in the extent to which they have the ability to implement sustainability initiatives. A number of factors are essential to be able to implement such initiatives: human capacity, availability of information, cooperation, and collaboration from the various groups and individuals who are essential to the initiative, as well as the finances to implement the initiatives (Wirtenberg et al., 2009). Organizations need to have management and employees knowledgeable in sustainability issues, suppliers certified to sustainability standards, as well as funds available for developing and implementing effective sustainability programs. Some organizations have the ability to analyze the risks, costs, and benefits of environmental and social issues and make well- informed decisions about current and future operations and current and future risks. Other organizations struggle with developing measures and metrics of sustainability (Epstein, 2008). Added to this, the benefits of sustainability can often be only measured over a long timeframe which makes it difficult for organizations to be able to measure the impact of social and environmental programs and to quantify the benefits of such programs. Hence, the degree to which an organization has the informational and analytical capacity to evaluate these issues may influence the relationship between sustainability beliefs and perceptions and implementation of sustainability initiatives. Thus, it was proposed: P13. Organizational capacity is likely to moderate the relationship between beliefs and perceptions about the importance and inconvenience of sustainability and the quantity and scope of environmental, social, and human sustainability initiatives implemented by organizations. Discussion This paper presents a model of the relationships between national cultural values, beliefs and perceptions about sustainability, and organizational sustainability initiatives. The model suggests that cultures low in power distance and high in collectivism, femininity, and long-term orientation are likely to hold stronger beliefsCCM needs" (World Commission on Economic Development, 1987, p. 8). This definition 22.2 has been adapted by scholars for the organizational context. Sustainable organizations can be considered those that "can sustain financial, human, social, and environmental resources over the long-term" (Bradbury, 2003, p. 173); these organizations play a significant role in sustainability in various ways: through the transfer of sustainability technology, through the education and training of employees, and through the 280 development of local communities. Our model proposes that national cultural values can influence sustainability beliefs and perceptions, which in turn influence the sustainability initiatives implemented by organizations. Thus, sustainability beliefs and perceptions can act as mediators in the relationship between national culture and organizational sustainability initiatives, and provide one possible explanation for how cultural values can influence sustainability initiatives. In addition, the model suggests that the relationship between sustainability beliefs and sustainability initiatives is moderated by the sustainability orientation of organizations and by organizational capacity (i.e. the information and resources available to the organization about sustainability issues and practices). The model goes on to propose relationships between five dimensions of national cultural values (power distance, individualism-collectivism, masculinity-femininity, uncertainty avoidance, and long-term vs short-term orientation), sustainability beliefs (perceived importance and perceived inconvenience of sustainability), and the scope, type, and number of sustainability initiatives (see Figure 1 for the model). The next section examines the various components of the model and describes the literature relating to each component. In addition, it discusses the relationships among the main constructs and formulates propositions that depict those relationships. National cultural values Culture [...] consists of ways of perceiving, thinking, and deciding that have worked in the past and have become institutionalized in standard operating procedures, customs, scripts and unstated assumptions that guide behavior (Triandis, 1995, p. 12). Organizational capacity - knowledge information - resources Beliefs and perceptions National cultural values about the importance of sustainability Quantity and scope of power distance sustainability initiatives - collectivism - environmental femininity - social long-term orientation human - uncertainty avoidance Beliefs and perceptions Figure 1. about the inconvenience of A conceptual model sustainability of national cultural values, sustainability perceptions, and Sustainability orientation organizational sustainability sustainability identity initiatives - strategic centrality systems alignmentsustainability initiatives. as well as initiatives of a broader scope. Hence. it was proposed: P10. Beliefs and perceptions about the importance of sustainability are likely to positively inuence the quantity and scope of environmental. social. and human sustainability initiatives implemented by organizations. In contrast to beliefs about the importance of sustainability. beliefs about the inconvenience of sustainability are likely to negatively inuence sustainability practices. The focus on costs and other inconveniences may come at the expense of sustainability; it can reduce responsiveness to environmental problems and result in slower adaptation of costly environmental technology by rms, especially if the benets of such technology do not result in immediate material gain (ushed. 3305). Beliefs about the inconvenience of sustainability can also hinder development programs such as those aimed at improving communities and alleviating poverty because individuals who oversee those programs may not be as concerned about program outcomes as about inconvenience: their professional advancement is more likely to be connected to the inuence of high level sponsors than their job performance (Husted. 2005}. Environmental issues can be ignored in the name of efciency; for example. political power holders in some countries accept the environmental waste of other countries. thus increasing their own political or material benets to the detriment of their people {Lopez and Mitra. 2000). In organizations. instructions from management to cut corners and use unsafe environmental practices are more likely when such practices are perceived as costly and inconvenient. Therefore, it was proposed: P11. Beliefs and perceptions about the inconvenience of sustainability are likely to negatively inuence the quantity and scope of environmental. social. and human sustainability initiatives implemented by organizations. Moderating effects of sustainability orientation and organizational capacity Our model proposes that the relationship between sustainability beliefs and perceptions and organizational sustainability initiatives is moderated by two constructs: sustainability orientation and organizational capacity. Each of these is discussed below. Sustaimbtty orientation This refers to the extent to which an organization demonstrates readiness to implement sustainability initiatives. It is manifested through system alignment {i.e. the degree to which the company's structure. systems and processes are aligned around sustainability). centrality of sustainability to business strategy. and the extent to which sustainability forms a core part of organizational identity {Wirtenberg at al. am}. Organizations differ in the extent to which they have developed systems to deal with environmental and social issues and have established technologies to use in implementing sustainability. Some organizathns may lack a coherent sustainability strategy and systematic thinking about managing the social and environmental impact of their processes. Others may have well-developed systems in place that enable them to examine the impact of their processes and activities on sustainability. These organizathns do not view sustainability narrowly as an operations issue or human resources issue or legal issue: they look at it as a system- wide design and alignment that needs to be implemented in the entire organization. and engage in actions such as capital investments. life cycle analyses. social and National cultural values 289 conditions, a higher level of sustainability [results]" (Park et cl, 2007, p. 105). Hence, sustainability may be context specific, with national culture playing a signicant role in inuencing how a society expects organizations and businesses to implement social and environmental issues (Ringov and Zollo, 2007}. Given such cultural differences, organizations need to tailor their sustainability initiatives to the local context. The objectives of this research are to add to the emerging literature on sustainability in organizations and to provide a prescription to multinationals implementing cross-country sustainability initiatives. Our model fulls these objectives by examining mediating variables. such as sustainability beliefs and perceptions, that explain the relationship between national cultural values and organizational sustainability initiatives. Two sustainability beliefs and perceptions are examined in the model: importance or the perceived benefits of sustainability and inconvenience or the perceived costs of sustainability. The model also includes two moderating variables: the sustainability orientation of organizations and organizational capacity to engage in sustainability initiatives. This model addresses three main limitations of the current literature. First, although several articles (e.g. Jackson and Apostolakau, 2010; Mueller at all, 2007; Rao, 2000} have conducted comparisons of sustainability practices between two or more countries, most have not specically examined the inuence of national culture on those practices. For example Jackson and Apostolakau, (2010) compared sustainability practices across 16 countries and Rao (2030) across four countries, but neither study specifically included national culture in their analyses. The few studies that do include culture as a variable show inconsistent findings; for example. some studies (Husted, 2005; Vachon, 2010} found that cultural values such as individualism positively inuenced sustainability, whereas others (Waldman ct cl, 2005} found that they negatively inuenced sustainability. The model developed in this paper can help clarify such inconsistencies in the literature on national culture and sustainability. Second, the few studies on culture and sustainability have only examined whether or not there is a link between national culture and sustainability, they have not investigated how national cultural values inuence sustainability initiatives. Our model identifies explanatory mechanisms that clarify how culture can inuence sustainability through the mediating inuence of sustainability beliefs and perceptions and how these differences in beliefs can result in different sustainability initiatives. Third, the studies on national cultural values and sustainability have largely focussed on sustainability at the societal level. It is important to also understand how national culture can inuence sustainability at the organizational level. Our model elucidates the factors that contribute to an organization' s implementation of various sustainability initiatives. This is especially important for multinational corporations that operate in different countries and regions of the world because such organizations need to pay special attention to the environmental and social impact of global operations and ensure that such issues are an integral part of their strategic decision-making process. Overall, our model can help researchers and managers better understand the meaning of sustainability in the context of international business, and increase their understanding of potential antecedents of successful sustainable development efforts across countries and cultures. Conceptual model The Brundtland Commission dened sustainability as \"that which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own National cultural values 279