I am reposting the same question because the previous respondent failed to comprehend the question and provided completely incorrect answers. It is an accounting assignment. I have compiled the expenses and am seeking assistance in calculating the breakeven point along with some recommendations. Please see through the case and let me know if I have anything wrong. I appreciate your help.

Questions:

- Based on a 50 percent markup, how many solar kits must be sold to break even in the first year?

- Make a recommendation to Drumond regarding whether or not Insolar should proceed with this venture.

I have compiled these on my own but not sure how to calculate the break-even point.

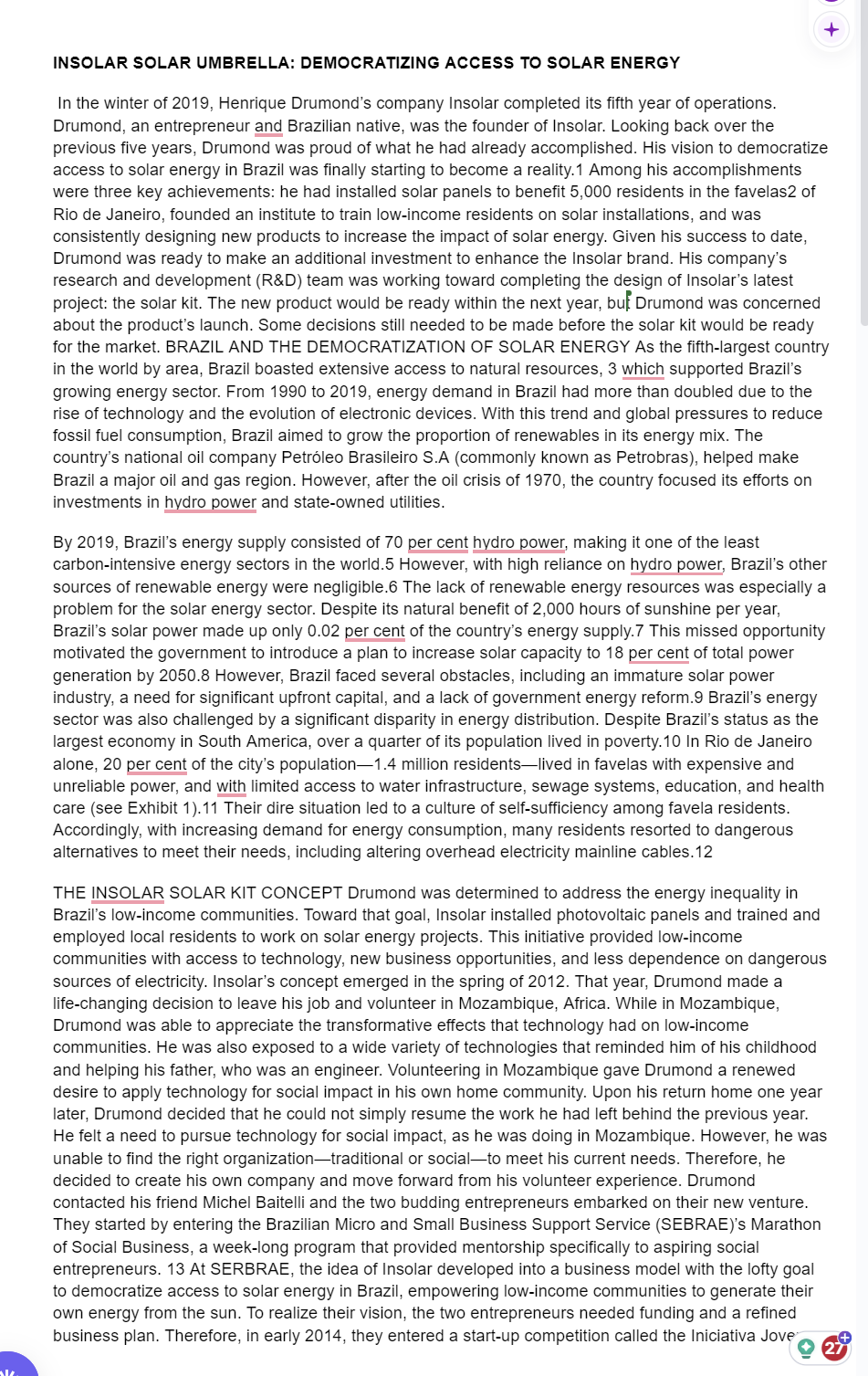

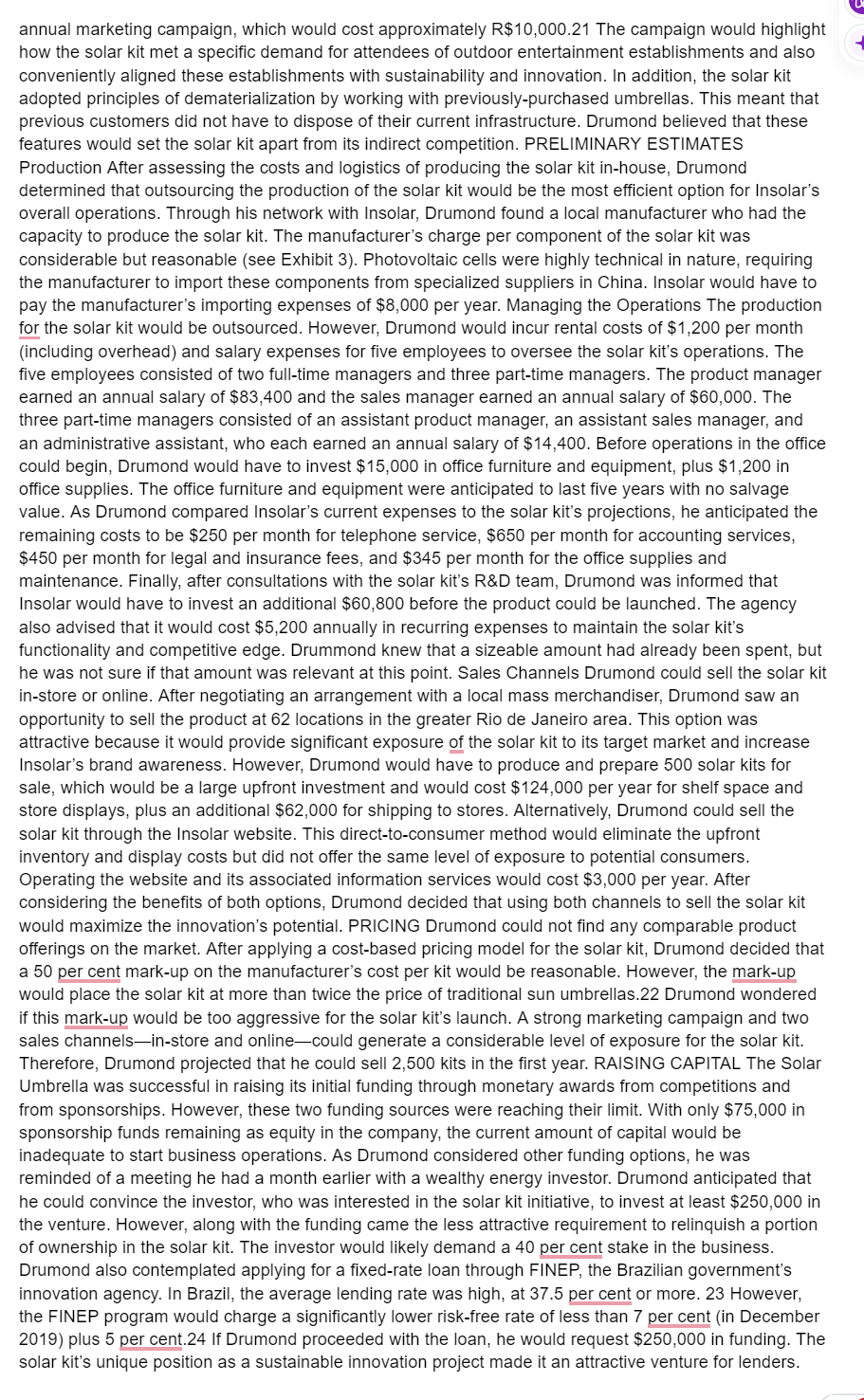

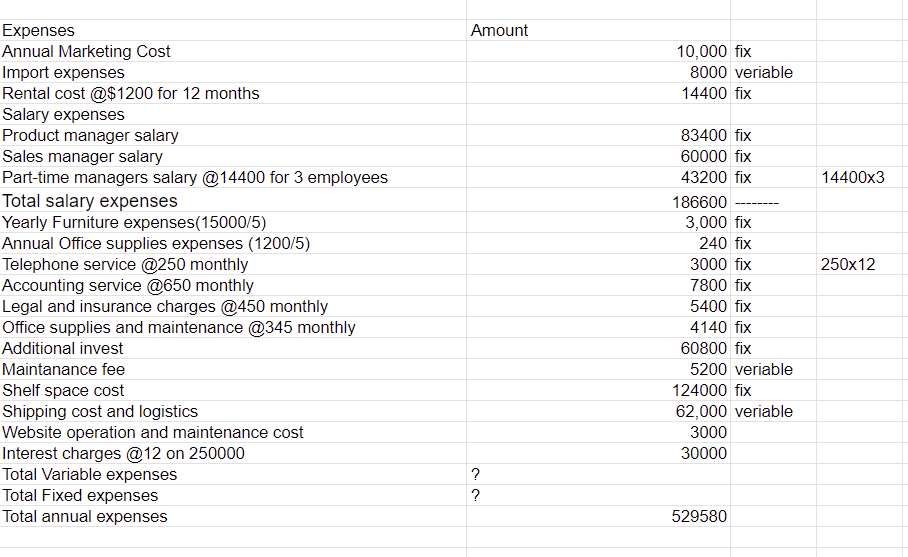

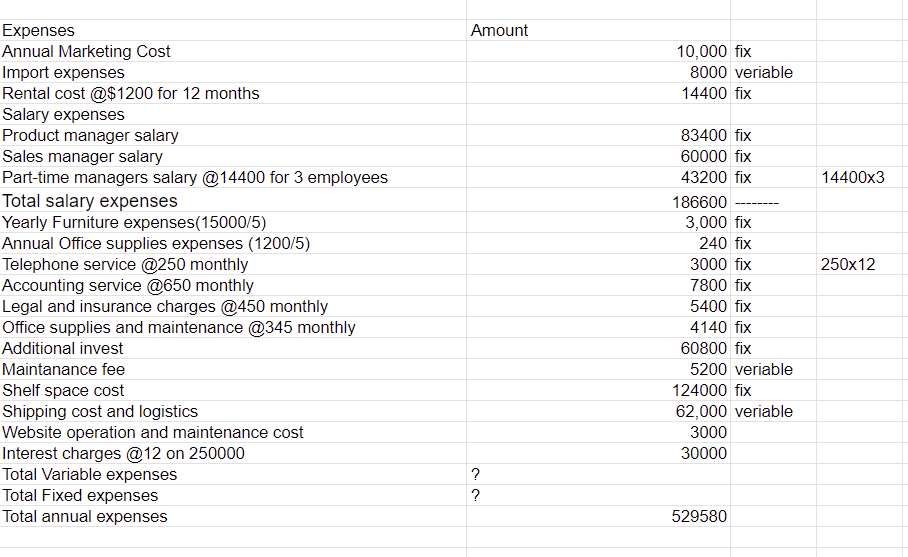

INSOLAR SOLAR UMBRELLA: DEMOCRATIZING ACCESS TO SOLAR ENERGY In the winter of 2019, Henrique Drumond's company Insolar completed its fifth year of operations. Drumond, an entrepreneur and Brazilian native, was the founder of Insolar. Looking back over the previous five years, Drumond was proud of what he had already accomplished. His vision to democratize access to solar energy in Brazil was finally starting to become a reality. 1 Among his accomplishments were three key achievements: he had installed solar panels to benefit 5,000 residents in the favelas 2 of Rio de Janeiro, founded an institute to train low-income residents on solar installations, and was consistently designing new products to increase the impact of solar energy. Given his success to date, Drumond was ready to make an additional investment to enhance the Insolar brand. His company's research and development (R\&D) team was working toward completing the design of Insolar's latest project: the solar kit. The new product would be ready within the next year, buf Drumond was concerned about the product's launch. Some decisions still needed to be made before the solar kit would be ready for the market. BRAZIL AND THE DEMOCRATIZATION OF SOLAR ENERGY As the fifth-largest country in the world by area, Brazil boasted extensive access to natural resources, 3 which supported Brazil's growing energy sector. From 1990 to 2019, energy demand in Brazil had more than doubled due to the rise of technology and the evolution of electronic devices. With this trend and global pressures to reduce fossil fuel consumption, Brazil aimed to grow the proportion of renewables in its energy mix. The country's national oil company Petrleo Brasileiro S.A (commonly known as Petrobras), helped make Brazil a major oil and gas region. However, after the oil crisis of 1970 , the country focused its efforts on investments in hydro power and state-owned utilities. By 2019, Brazil's energy supply consisted of 70 per cent hydro power, making it one of the least carbon-intensive energy sectors in the world. 5 However, with high reliance on hydro power, Brazil's other sources of renewable energy were negligible. 6 The lack of renewable energy resources was especially a problem for the solar energy sector. Despite its natural benefit of 2,000 hours of sunshine per year, Brazil's solar power made up only 0.02 per cent of the country's energy supply. 7 This missed opportunity motivated the government to introduce a plan to increase solar capacity to 18 per cent of total power generation by 2050.8 However, Brazil faced several obstacles, including an immature solar power industry, a need for significant upfront capital, and a lack of government energy reform. 9 Brazil's energy sector was also challenged by a significant disparity in energy distribution. Despite Brazil's status as the largest economy in South America, over a quarter of its population lived in poverty. 10 In Rio de Janeiro alone, 20 per cent of the city's population-1.4 million residents-lived in favelas with expensive and unreliable power, and with limited access to water infrastructure, sewage systems, education, and health care (see Exhibit 1).11 Their dire situation led to a culture of self-sufficiency among favela residents. Accordingly, with increasing demand for energy consumption, many residents resorted to dangerous alternatives to meet their needs, including altering overhead electricity mainline cables. 12 THE INSOLAR SOLAR KIT CONCEPT Drumond was determined to address the energy inequality in Brazil's low-income communities. Toward that goal, Insolar installed photovoltaic panels and trained and employed local residents to work on solar energy projects. This initiative provided low-income communities with access to technology, new business opportunities, and less dependence on dangerous sources of electricity. Insolar's concept emerged in the spring of 2012. That year, Drumond made a life-changing decision to leave his job and volunteer in Mozambique, Africa. While in Mozambique, Drumond was able to appreciate the transformative effects that technology had on low-income communities. He was also exposed to a wide variety of technologies that reminded him of his childhood and helping his father, who was an engineer. Volunteering in Mozambique gave Drumond a renewed desire to apply technology for social impact in his own home community. Upon his return home one year later, Drumond decided that he could not simply resume the work he had left behind the previous year. He felt a need to pursue technology for social impact, as he was doing in Mozambique. However, he was unable to find the right organizationtraditional or social-to meet his current needs. Therefore, he decided to create his own company and move forward from his volunteer experience. Drumond contacted his friend Michel Baitelli and the two budding entrepreneurs embarked on their new venture. They started by entering the Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service (SEBRAE)'s Marathon of Social Business, a week-long program that provided mentorship specifically to aspiring social entrepreneurs. 13 At SERBRAE, the idea of Insolar developed into a business model with the lofty goal to democratize access to solar energy in Brazil, empowering low-income communities to generate their own energy from the sun. To realize their vision, the two entrepreneurs needed funding and a refined business plan. Therefore, in early 2014, they entered a start-up competition called the Iniciativa Jove annual marketing campaign, which would cost approximately R$10,000.21 The campaign would highlight how the solar kit met a specific demand for attendees of outdoor entertainment establishments and also conveniently aligned these establishments with sustainability and innovation. In addition, the solar kit adopted principles of dematerialization by working with previously-purchased umbrellas. This meant that previous customers did not have to dispose of their current infrastructure. Drumond believed that these features would set the solar kit apart from its indirect competition. PRELIMINARY ESTIMATES Production After assessing the costs and logistics of producing the solar kit in-house, Drumond determined that outsourcing the production of the solar kit would be the most efficient option for Insolar's overall operations. Through his network with Insolar, Drumond found a local manufacturer who had the capacity to produce the solar kit. The manufacturer's charge per component of the solar kit was considerable but reasonable (see Exhibit 3). Photovoltaic cells were highly technical in nature, requiring the manufacturer to import these components from specialized suppliers in China. Insolar would have to pay the manufacturer's importing expenses of $8,000 per year. Managing the Operations The production for the solar kit would be outsourced. However, Drumond would incur rental costs of $1,200 per month (including overhead) and salary expenses for five employees to oversee the solar kit's operations. The five employees consisted of two full-time managers and three part-time managers. The product manager earned an annual salary of $83,400 and the sales manager earned an annual salary of $60,000. The three part-time managers consisted of an assistant product manager, an assistant sales manager, and an administrative assistant, who each earned an annual salary of $14,400. Before operations in the office could begin, Drumond would have to invest $15,000 in office furniture and equipment, plus $1,200 in office supplies. The office furniture and equipment were anticipated to last five years with no salvage value. As Drumond compared Insolar's current expenses to the solar kit's projections, he anticipated the remaining costs to be $250 per month for telephone service, $650 per month for accounting services, $450 per month for legal and insurance fees, and $345 per month for the office supplies and maintenance. Finally, after consultations with the solar kit's R\&D team, Drumond was informed that Insolar would have to invest an additional $60,800 before the product could be launched. The agency also advised that it would cost $5,200 annually in recurring expenses to maintain the solar kit's functionality and competitive edge. Drummond knew that a sizeable amount had already been spent, but he was not sure if that amount was relevant at this point. Sales Channels Drumond could sell the solar kit in-store or online. After negotiating an arrangement with a local mass merchandiser, Drumond saw an opportunity to sell the product at 62 locations in the greater Rio de Janeiro area. This option was attractive because it would provide significant exposure of the solar kit to its target market and increase Insolar's brand awareness. However, Drumond would have to produce and prepare 500 solar kits for sale, which would be a large upfront investment and would cost $124,000 per year for shelf space and store displays, plus an additional $62,000 for shipping to stores. Alternatively, Drumond could sell the solar kit through the Insolar website. This direct-to-consumer method would eliminate the upfront inventory and display costs but did not offer the same level of exposure to potential consumers. Operating the website and its associated information services would cost $3,000 per year. After considering the benefits of both options, Drumond decided that using both channels to sell the solar kit would maximize the innovation's potential. PRICING Drumond could not find any comparable product offerings on the market. After applying a cost-based pricing model for the solar kit, Drumond decided that a 50 per cent mark-up on the manufacturer's cost per kit would be reasonable. However, the mark-up would place the solar kit at more than twice the price of traditional sun umbrellas.22 Drumond wondered if this mark-up would be too aggressive for the solar kit's launch. A strong marketing campaign and two sales channels-in-store and online-could generate a considerable level of exposure for the solar kit. Therefore, Drumond projected that he could sell 2,500 kits in the first year. RAISING CAPITAL The Solar Umbrella was successful in raising its initial funding through monetary awards from competitions and from sponsorships. However, these two funding sources were reaching their limit. With only $75,000 in sponsorship funds remaining as equity in the company, the current amount of capital would be inadequate to start business operations. As Drumond considered other funding options, he was reminded of a meeting he had a month earlier with a wealthy energy investor. Drumond anticipated that he could convince the investor, who was interested in the solar kit initiative, to invest at least $250,000 in the venture. However, along with the funding came the less attractive requirement to relinquish a portion of ownership in the solar kit. The investor would likely demand a 40 per cent stake in the business. Drumond also contemplated applying for a fixed-rate loan through FINEP, the Brazilian government's innovation agency. In Brazil, the average lending rate was high, at 37.5 per cent or more. 23 However, the FINEP program would charge a significantly lower risk-free rate of less than 7 per cent (in December 2019) plus 5 per cent.24 If Drumond proceeded with the loan, he would request $250,000 in funding. The solar kit's unique position as a sustainable innovation project made it an attractive venture for lenders. INSOLAR SOLAR UMBRELLA: DEMOCRATIZING ACCESS TO SOLAR ENERGY In the winter of 2019, Henrique Drumond's company Insolar completed its fifth year of operations. Drumond, an entrepreneur and Brazilian native, was the founder of Insolar. Looking back over the previous five years, Drumond was proud of what he had already accomplished. His vision to democratize access to solar energy in Brazil was finally starting to become a reality. 1 Among his accomplishments were three key achievements: he had installed solar panels to benefit 5,000 residents in the favelas 2 of Rio de Janeiro, founded an institute to train low-income residents on solar installations, and was consistently designing new products to increase the impact of solar energy. Given his success to date, Drumond was ready to make an additional investment to enhance the Insolar brand. His company's research and development (R\&D) team was working toward completing the design of Insolar's latest project: the solar kit. The new product would be ready within the next year, buf Drumond was concerned about the product's launch. Some decisions still needed to be made before the solar kit would be ready for the market. BRAZIL AND THE DEMOCRATIZATION OF SOLAR ENERGY As the fifth-largest country in the world by area, Brazil boasted extensive access to natural resources, 3 which supported Brazil's growing energy sector. From 1990 to 2019, energy demand in Brazil had more than doubled due to the rise of technology and the evolution of electronic devices. With this trend and global pressures to reduce fossil fuel consumption, Brazil aimed to grow the proportion of renewables in its energy mix. The country's national oil company Petrleo Brasileiro S.A (commonly known as Petrobras), helped make Brazil a major oil and gas region. However, after the oil crisis of 1970 , the country focused its efforts on investments in hydro power and state-owned utilities. By 2019, Brazil's energy supply consisted of 70 per cent hydro power, making it one of the least carbon-intensive energy sectors in the world. 5 However, with high reliance on hydro power, Brazil's other sources of renewable energy were negligible. 6 The lack of renewable energy resources was especially a problem for the solar energy sector. Despite its natural benefit of 2,000 hours of sunshine per year, Brazil's solar power made up only 0.02 per cent of the country's energy supply. 7 This missed opportunity motivated the government to introduce a plan to increase solar capacity to 18 per cent of total power generation by 2050.8 However, Brazil faced several obstacles, including an immature solar power industry, a need for significant upfront capital, and a lack of government energy reform. 9 Brazil's energy sector was also challenged by a significant disparity in energy distribution. Despite Brazil's status as the largest economy in South America, over a quarter of its population lived in poverty. 10 In Rio de Janeiro alone, 20 per cent of the city's population-1.4 million residents-lived in favelas with expensive and unreliable power, and with limited access to water infrastructure, sewage systems, education, and health care (see Exhibit 1).11 Their dire situation led to a culture of self-sufficiency among favela residents. Accordingly, with increasing demand for energy consumption, many residents resorted to dangerous alternatives to meet their needs, including altering overhead electricity mainline cables. 12 THE INSOLAR SOLAR KIT CONCEPT Drumond was determined to address the energy inequality in Brazil's low-income communities. Toward that goal, Insolar installed photovoltaic panels and trained and employed local residents to work on solar energy projects. This initiative provided low-income communities with access to technology, new business opportunities, and less dependence on dangerous sources of electricity. Insolar's concept emerged in the spring of 2012. That year, Drumond made a life-changing decision to leave his job and volunteer in Mozambique, Africa. While in Mozambique, Drumond was able to appreciate the transformative effects that technology had on low-income communities. He was also exposed to a wide variety of technologies that reminded him of his childhood and helping his father, who was an engineer. Volunteering in Mozambique gave Drumond a renewed desire to apply technology for social impact in his own home community. Upon his return home one year later, Drumond decided that he could not simply resume the work he had left behind the previous year. He felt a need to pursue technology for social impact, as he was doing in Mozambique. However, he was unable to find the right organizationtraditional or social-to meet his current needs. Therefore, he decided to create his own company and move forward from his volunteer experience. Drumond contacted his friend Michel Baitelli and the two budding entrepreneurs embarked on their new venture. They started by entering the Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service (SEBRAE)'s Marathon of Social Business, a week-long program that provided mentorship specifically to aspiring social entrepreneurs. 13 At SERBRAE, the idea of Insolar developed into a business model with the lofty goal to democratize access to solar energy in Brazil, empowering low-income communities to generate their own energy from the sun. To realize their vision, the two entrepreneurs needed funding and a refined business plan. Therefore, in early 2014, they entered a start-up competition called the Iniciativa Jove annual marketing campaign, which would cost approximately R$10,000.21 The campaign would highlight how the solar kit met a specific demand for attendees of outdoor entertainment establishments and also conveniently aligned these establishments with sustainability and innovation. In addition, the solar kit adopted principles of dematerialization by working with previously-purchased umbrellas. This meant that previous customers did not have to dispose of their current infrastructure. Drumond believed that these features would set the solar kit apart from its indirect competition. PRELIMINARY ESTIMATES Production After assessing the costs and logistics of producing the solar kit in-house, Drumond determined that outsourcing the production of the solar kit would be the most efficient option for Insolar's overall operations. Through his network with Insolar, Drumond found a local manufacturer who had the capacity to produce the solar kit. The manufacturer's charge per component of the solar kit was considerable but reasonable (see Exhibit 3). Photovoltaic cells were highly technical in nature, requiring the manufacturer to import these components from specialized suppliers in China. Insolar would have to pay the manufacturer's importing expenses of $8,000 per year. Managing the Operations The production for the solar kit would be outsourced. However, Drumond would incur rental costs of $1,200 per month (including overhead) and salary expenses for five employees to oversee the solar kit's operations. The five employees consisted of two full-time managers and three part-time managers. The product manager earned an annual salary of $83,400 and the sales manager earned an annual salary of $60,000. The three part-time managers consisted of an assistant product manager, an assistant sales manager, and an administrative assistant, who each earned an annual salary of $14,400. Before operations in the office could begin, Drumond would have to invest $15,000 in office furniture and equipment, plus $1,200 in office supplies. The office furniture and equipment were anticipated to last five years with no salvage value. As Drumond compared Insolar's current expenses to the solar kit's projections, he anticipated the remaining costs to be $250 per month for telephone service, $650 per month for accounting services, $450 per month for legal and insurance fees, and $345 per month for the office supplies and maintenance. Finally, after consultations with the solar kit's R\&D team, Drumond was informed that Insolar would have to invest an additional $60,800 before the product could be launched. The agency also advised that it would cost $5,200 annually in recurring expenses to maintain the solar kit's functionality and competitive edge. Drummond knew that a sizeable amount had already been spent, but he was not sure if that amount was relevant at this point. Sales Channels Drumond could sell the solar kit in-store or online. After negotiating an arrangement with a local mass merchandiser, Drumond saw an opportunity to sell the product at 62 locations in the greater Rio de Janeiro area. This option was attractive because it would provide significant exposure of the solar kit to its target market and increase Insolar's brand awareness. However, Drumond would have to produce and prepare 500 solar kits for sale, which would be a large upfront investment and would cost $124,000 per year for shelf space and store displays, plus an additional $62,000 for shipping to stores. Alternatively, Drumond could sell the solar kit through the Insolar website. This direct-to-consumer method would eliminate the upfront inventory and display costs but did not offer the same level of exposure to potential consumers. Operating the website and its associated information services would cost $3,000 per year. After considering the benefits of both options, Drumond decided that using both channels to sell the solar kit would maximize the innovation's potential. PRICING Drumond could not find any comparable product offerings on the market. After applying a cost-based pricing model for the solar kit, Drumond decided that a 50 per cent mark-up on the manufacturer's cost per kit would be reasonable. However, the mark-up would place the solar kit at more than twice the price of traditional sun umbrellas.22 Drumond wondered if this mark-up would be too aggressive for the solar kit's launch. A strong marketing campaign and two sales channels-in-store and online-could generate a considerable level of exposure for the solar kit. Therefore, Drumond projected that he could sell 2,500 kits in the first year. RAISING CAPITAL The Solar Umbrella was successful in raising its initial funding through monetary awards from competitions and from sponsorships. However, these two funding sources were reaching their limit. With only $75,000 in sponsorship funds remaining as equity in the company, the current amount of capital would be inadequate to start business operations. As Drumond considered other funding options, he was reminded of a meeting he had a month earlier with a wealthy energy investor. Drumond anticipated that he could convince the investor, who was interested in the solar kit initiative, to invest at least $250,000 in the venture. However, along with the funding came the less attractive requirement to relinquish a portion of ownership in the solar kit. The investor would likely demand a 40 per cent stake in the business. Drumond also contemplated applying for a fixed-rate loan through FINEP, the Brazilian government's innovation agency. In Brazil, the average lending rate was high, at 37.5 per cent or more. 23 However, the FINEP program would charge a significantly lower risk-free rate of less than 7 per cent (in December 2019) plus 5 per cent.24 If Drumond proceeded with the loan, he would request $250,000 in funding. The solar kit's unique position as a sustainable innovation project made it an attractive venture for lenders