Question

In June of 1987, Charlie Leonard began searching for a small income-producing apartment building in which to invest. Leonard had just graduated from Harvard College,

In June of 1987, Charlie Leonard began searching for a small income-producing apartment building in which to invest. Leonard had just graduated from Harvard College, and he was working for a manufacturing firm in Newton, Massachusetts. He had grown up in Boston and was attracted to the investment potential of the Back Bay-Beacon Hill area, which he considered the best residential section of downtown Boston. Many of his contemporaries were renting apartments or had purchased homes there, and he and his wife had attended many of their parties. He considered paying rent to someone else a waste of a capital building opportunity, since he was building up someone else's equity.

Leonard wanted to gain experience in the real estate field, and build an equity base for future

real estate investments. He hoped to increase his return by managing and operating his property on weekends and after normal working hours. Leonard had recently received an inheritance from a great aunt of $25,000, and he wanted to achieve maximum leverage for this equity. Although he had no real estate experience, he had a working knowledge of carpentry from three years of designing and building sets for Harvard's Hasty Pudding Show.

Beacon Hill Properties

Leonard began to spend all his free evenings and weekends becoming familiar with the area.

He obtained a copy of the U.S. Census Tract, Boston Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA) to check the demographic data on age breakdowns, education, employment, marital status, income, length of stay, and ethnic background of present Beacon Hill residents. Most were transient, and either single or newly married. He checked maps for distances to the city's office, shopping, cultural, and entertainment centers, and found that Beacon Hill was close to all of these urban amenities.

He studied the real estate sections of newspapers for brokers' names and to get an

idea of the types of offerings and range of prices available. He found that the Sunday papers had by far the largest real estate advertising sections. He answered some advertisements in order to meet real estate brokers, and learn about the available properties. He specifically attempted to visit those offices that did the most advertising (or that appeared to do the most business in the area). Many were located around Charles Street, the major commercial street of Beacon Hill. Normally, the brokers wanted to know the type of property in which he was interested, the amount of cash he had to invest, and whether he would live in the building. Leonard was quite disappointed in the offerings that were shown to him. Although the income and expense statements of one building on Myrtle Street had made it seem quite attractive, the situation was very different when he actually visited the building. It was in a rundown state, and the apartments, occupied by groups of students, were in deplorable condition. The income statement of another property on Myrtle Street showed a 20% return on the cash investment; however, this made no allowance for repairs, vacancies, or management expenses. When considered, these costs reduced the return to 3%. Rentals in another building seemed too high. When Leonard spoke with one of the tenants, he found that the landlord had asked a rental of $810 per month for the apartment, but, when offered $675 per month, accepted on the condition that there be a one-year lease with no rent the first two months and then $810 rent per month for the remainder of the term. This arrangement would enable the landlord to show a higher monthly income after the initial two months.

Most properties sold for $270,000 and higher, and required an investment of more than $25,000. Leonard expected to obtain a bank loan for part of the purchase price through a mortgage (a legal instrument by which property is hypothecated to secure the payment of a debt or obligation).

But institutional lenders were reluctant to lend more than 60-80% of the capitalized value of the property. Additional money might be raised by placing a second or junior mortgage on the property, but interest rates on this type of secondary financing were higher, and the personal credit of the borrower was often required as additional collateral. However, sellers were often willing to take a purchase money mortgage to facilitate the sale of the property. Nevertheless, having only $25,000 equity proved a major factor in limiting the building Leonard might purchase.

Leonard became discouraged. Although the real estate brokers were friendly, they never seemed to show him what he considered desirable properties. There rarely appeared to be an opportunity to create value by increasing rents or reducing expenses; if there were, the seller had already taken it into consideration in establishing his price. Leonard soon learned that many of the brokers owned buildings themselves, and were thus, in a sense, competitors of their own customers.

Few properties in the area were sold by the owners themselves. Usually they were listed with several brokers who competed to receive a 5% sales commission by selling the property to one of their customers. Since there was considerable investor interest in the area, and listings were rarely exclusive with one broker, the brokers had to act quickly on the desirable properties to make their commissions. Therefore, most of the brokers had a few favored customers to whom they gave first chance. These customers usually had the necessary resources to act quickly to acquire the most desirable situations.

Factors Affecting Value

The same factors which caused Leonard to want to purchase on Beacon Hill had attracted many doctors, engineers, and businessmen also anxious to own real estate. As a result, the market values of many buildings on the Hill had tripled in the past ten years.

The area's location had considerable natural advantages. To the west was the Charles River;

to the south was the Boston Public Gardens which led to Newbury Street, Boston's best shopping area; and to the east was the State House and Boston's financial district. The West End slums and the undesirable commercial activity of adjacent Scollay Square to the north had restrained values in the 1940s and 1950s. This had been especially true of the northern slope of the Hill, which had become known as the "back slope because of its many lower-rent rooming houses. Under Boston's urban redevelopment program, however, in the 1960s and 1970s, the West End slums were torn down and were replaced by Charles River Park, a luxury apartment house development. Scollay Square was replaced by a new Government Center.

As a result of this redevelopment, values all over Beacon Hill had increased, but most

drastically on the back or north slope. Rentals and condominium values there had increased as real estate operators began to buy and improve the property. Rents now ranged from $675-$800 for one-bedroom apartments and $900-$1100 for two-bedroom apartments. In spite of this, because most purchasers in this section were real estate speculators who expected a high return on their investment, Leonard felt there would be further growth as investors who were accustomed to lower returns from properties on the lower section of the Hill began to buy buildings on the north slope from these real estate speculators. The recent conversion of rental units to condominiums also caused values to increase.

The Massachusetts State Legislature had established the entire Beacon Hill area as an historic district, and set up a commission to preserve the character of the area. The approval of the commission had to be obtained for any changes to the exterior of a structure before the building department would issue a building permit. The commission would not permit the erection of any new buildings in the area. While this protected and enhanced the values of existing buildings, it provided a ceiling on land values, since land could not be reused for a different, more valuable purpose.

Leonard knew that this activity and interest in the area, which had driven prices up and was proving a disadvantage in his attempts to buy a property, would turn into an advantage once he owned a building. Many investors in Beacon Hill appeared to be satisfied with an 8% return on cash, which meant that for every $1,000 of cash flow, which remained after deducting all charges or costs from gross income, he could expect a buyer to pay $12,500. In some areas an investor might look for a 12.5% return, in which case $1,000 of cash flow would be worth only $8,000.

All of these factors led Leonard to believe that there was considerable safety in an investment

in the area. There was little chance of depreciation for functional or economic causes. To obtain maximum capital appreciation, however, he would probably have to narrow his investment search to the back slope of Beacon Hill, where values were still not as high as on the "lower slope." He also realized that he would have to purchase a building that would require considerable renovation.

Otherwise, once the income had become established the owner would ask a high selling price that would preclude much short-term growth in value. He had learned that he would have to act quickly if he did find an attractive opportunity. He would also have to check all figures given him carefully since few small buildings had audited financial statements and he could not rely solely on statements made by real estate brokers. Lastly, he knew that his $25,000 equity would limit him to acquiring a relatively small building.

Anderson Street

In August of 1987, Leonard learned of a 4-unit apartment house on Beacon Hill that was for sale. A local broker with whom he was friendly had called to tell him that a building on Anderson Street had just come on the market, and that if he acted quickly, he might be able to outbid several real estate brokers who were interested in the property. Leonard knew that brokers always attempted to convey a sense of urgency, but since he was aware that desirable properties did sell quickly, he decided to investigate the property at once.

The property was located on the "back slope of the Hill" in an improving neighborhood.

There had already been some increases in property values, and Leonard expected still greater increases as little new housing was being built in Boston. The property was located in the middle of the block, and was set back 100 feet from the road, which would afford an opportunity for creating an attractive entrance way and garden. The property had been built in the mid-1800s, probably as a middle-income town house. After being used as a rooming house for 20 years it had been gutted by a fire in 1986. Only the structural shell remained. An architect had purchased the shell for $120,000, but after spending $45,000 of what looked to be a $100,000 renovation job, he decided the total cost was beyond his cash available and placed the property on the market. Leonard felt that the architect's plans for renovation were in good taste and that thus far the work had been done well.

Each of the first three floors was to have one two-bedroom apartment while the fourth floor would have a large one-bedroom apartment. For the first time, Leonard felt that he had seen a property that met his investment criteria. The property had profit potential; it was aesthetically desirable, in the area he wanted, and, with an asking price of $168,000, was within his price range.

Leonard was told that the $168,000 price was firm because considerable interest had already been shown in the property. A contractor to whom Leonard was referred confirmed that it would cost approximately $55,000 to complete the architect's plans.

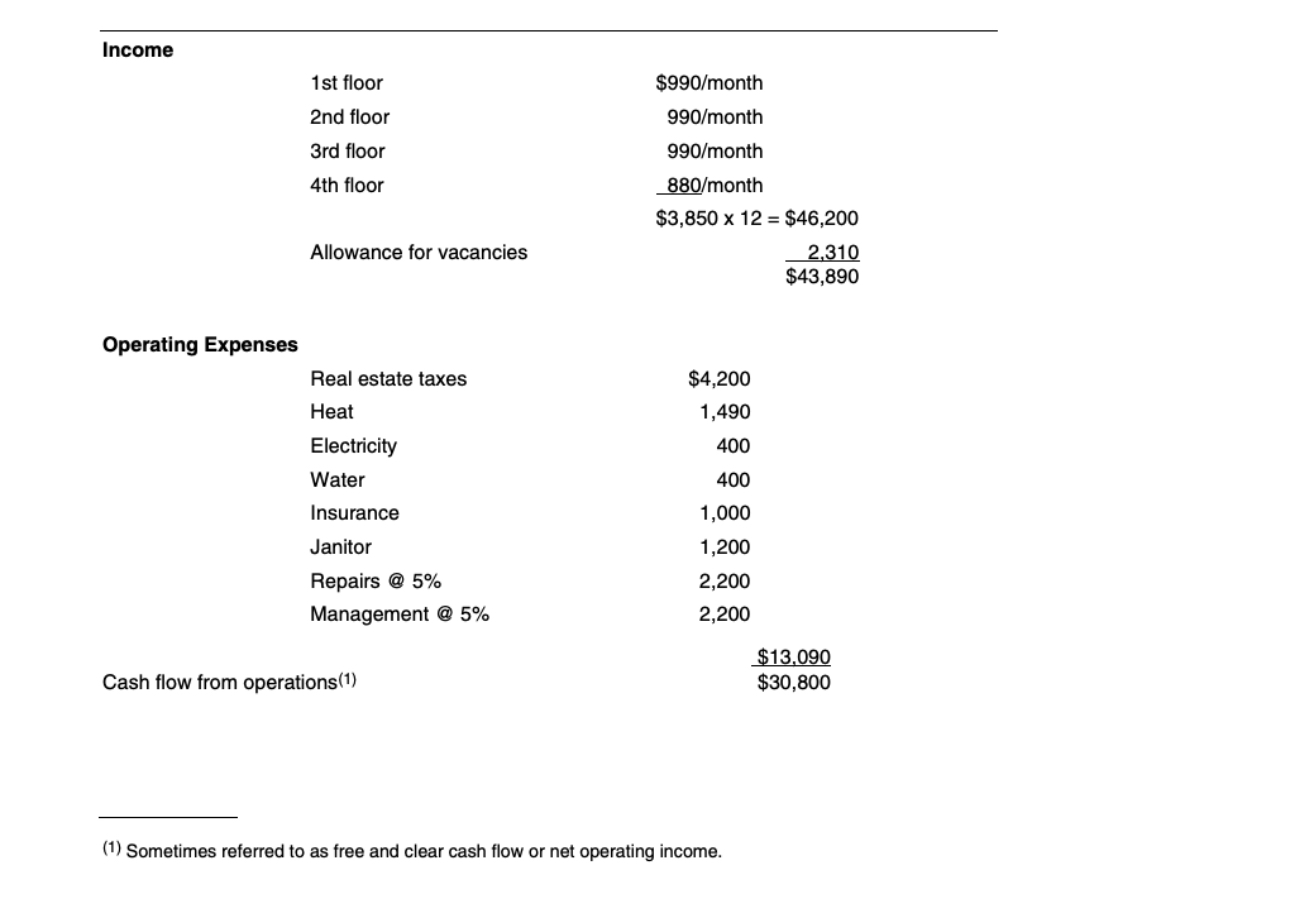

Leonard prepared an income and expense statement to see whether the net income of the property would justify its price (see Exhibit 1). He figured that each of the three two-bedroom apartments could be rented at $990 per month, and the top floor one-bedroom apartment at $880 per month. Rentals would total $46,200 annually. From this figure, he subtracted a 5% vacancy allowance, which would represent two apartments sitting vacant for slightly more than a month.

There was the additional possibility that if he did not rent the apartments himself, he would have to pay a broker's commission of 5% of the annual apartment rental. The broker, licensed by the state, received this commission for showing the property to prospective tenants, from bringing the tenants and landlord together, and helping to negotiate the contract between them.

Leonard estimated real estate taxes at 9.5% of the rental income or $4,200. This represented

an assessed value of $250,000, which was approximately full market value, and $75,000 above the present $175,000 assessment. He obtained a quotation of a $1,000 annual premium from his real estate broker's firm for a package insurance policy providing protection against fire, extended coverage perils, public liability, loss of rents, and boiler explosion. The tenants would pay the electric bills for their own apartments, but the landlord would pay the bill for the public areas. A janitor would keep the public halls clean, change the light bulbs, and take out the trash. There were several services around Beacon Hill that performed this function for an annual fee of $1,200. Leonard had expected to do some of the repair work and all of the management work himself to increase his cash return, but his broker told him that since potential mortgage lenders or future purchasers would include these costs in their "setups," Leonard would have to do so, too. Also, if he should leave the area, he would have to hire outside firms to perform these services. Therefore, he included an allowance of 5% for repairs and a similar amount for management. His projections showed a cash flow before financing of $30,800, without any allowance for the work he would do himself. (See Exhibit 1.)

Leonard was very pleased. He told his wife that he had found a building that would be just right. With its skylights, beamed ceiling, and natural brick walls, the top floor apartment was just what they wanted to live in. They could live "rent free," while making money by doing their own managing and renting. They could take out the trash and clean the halls themselves. Although outside management would be more experienced, he would be more attentive and efficient. Rent from the other apartments would pay the other expenses, and he would gain real estate experience.

His wife said that while the apartment seemed very nice, she was not sure she liked the idea of living in a building they owned. They would get tenants' complaints at home. Also, she thought there might be a problem in doing business with their neighbors if they got friendly with them. She doubted that they would be able to charge maximum rents or raise rents.

The real estate broker questioned his decision to act as his own general contractor because of his lack of experience and time. He said that it was difficult, particularly on a part-time basis, to coordinate several subcontractors who never showed up when they said they would. The work might take longer than Leonard anticipated. Also, the Boston Building Department had a maze of rules and many inspectors; his renovation could be quite costly if he were forced to comply exactly with every regulation. Experienced contractors usually found ways of getting around these requirements. He would have to be careful however, to minimize changes and avoid extras once the job had been started, since most subcontractors would charge a premium for extras, because it would be too late to get competitive quotes on small amounts of work.

Leonard replied that any remodeling job would involve changes in adapting to field conditions. One of the reasons he wanted to do the work himself was to avoid the extra charges by subcontractors. Any outside contractor would carry a heavy contingency allowance in bidding the job. Certainly the contractor who gave him the $55,000 estimate to complete the renovation must have carried at least $5,000 for profit. Leonard reasoned that he had at least that $5,000 to spend before his lesson in remodeling began to cost him money.

Mortgage Financing

Leonard then went to see Jerry Smith, the mortgage officer of the savings bank who had recently given a $180,000 loan on the building for a 20 year period at a 10% interest rate. Smith told him that the existing mortgage was on a constant payment basis of 11.6% or $20,900 per year, which meant that the payments, including amortization and interest, remained the same throughout the entire term of the loan, but that the portion applicable to interest became less as the balance of the mortgage loan decreased. Correspondingly, the portion applicable to amortization increased. The mortgage payment plus a payment of one-twelfth of the estimated real estate taxes were made to the bank monthly. The bank also kept two months' real estate taxes in escrow as additional security. The banker explained that the loan could be paid off at any time, but that it would charge a prepayment penalty of 2% of the unpaid balance.

Leonard explained his plans for finishing the work and gave Smith his projected income and expense statements for the property. Smith noticed that Leonard's rental figures were $5,600 higher than those originally submitted by the present owner. At that time the bank had valued the property at $225,000 and given an 80% mortgage, the maximum permitted by bank policy. He asked whether Leonard knew his total costs. Leonard told him of the contractor's $55,000 bid. Smith told him that he should also consider carrying costs while the renovation work was going on. The bank might waive principal payments on the mortgage for six months during construction, but interest of $9,000 on the $180,000 must be paid, as well as real estate taxes of $1,400 assuming the $175,000 assessment would remain in effect until the renovation was complete. In addition, he still had to pay for six months' insurance at $500 and heat and electricity at $1,100. These costs totalled $12,000. There was also the two-month real estate tax escrow of $1,000, which was a cash outlay even though it would eventually be returned to him. Leonard could but did not need to assume the architect's existing mortgage, thus eliminating the need for new documents and a new title search by the bank's lawyer.

(Assumption of a mortgage occurs when, in purchasing a property, the buyer assumes liability for payment of an existing note secured by a mortgage on the property.)

He asked whether the bank would increase its mortgage to $210,000. He explained that he might live in the building, manage it, and do some of the work himself, which would create more cash flow to serve the debt. The banker replied that he could not take this extra income into account in making his decision, since the bank always had to consider a loan in light of the costs the bank would incur if it had to foreclose and run the property itself. (A foreclosure sale occurs when property pledged as security for a loan is sold to pay the debt in the event of a default in payment or terms.)

Smith doubted that the bank would be interested in increasing its loan at this time since it was not certain that Leonard could get the increased rentals. However, Smith added that if the income level was increased when the building became rented and seasoned, the bank might reexamine his request.

Leonard next visited Sarah Harris, the mortgage loan officer at another local savings bank, to find out whether her bank would be interested in a $210,000 mortgage. Leonard showed her the income and expense projections, told her his costs, and explained his plans. Harris said that because of the 80% policy restriction, her bank would have to appraise the property at $262,500 to justify a $210,000 loan. Appraisals, she told Leonard, could be made on the basis of replacement cost, income, or market value based on recent comparable sales. She said that her bank preferred the income approach as the most realistic. Taking a capitalization rate of 11.6% on the $30,800 projected cash flow, she arrived at an appraised value of $265,500. Harris considered it likely that based on this appraisal she could justify a $210,000 mortgage at 10% interest for 20 years. She believed that the $30,800 annual cash flow from operations would be adequate to carry the $24,300 financing charge.

She added that she was familiar with the area and considered Leonard's projected figures realistic, although she would have to see the property to be certain of her judgment.

She questioned Leonard about his current personal income. Leonard told her that his present salary was $26,000 per year. Harris said she would require credit references and certain other information about Leonard since he would be signing the note personally as additional protection to the bank against loss. Leonard asked why he would have to become personally liable since there was ample value in the property. He knew that his friends who had bought brownstones in New York had not assumed any personal liability. Harris said that this was the policy of virtually all savings banks in the Boston area for smaller buildings, especially when the loan to value ratio was as high as 80%. If Leonard had confidence in the building, he should not worry. Each year his liability declined as a portion of the mortgage loan was amortized.

Leonard asked whether there were other costs in closing the mortgage. Harris replied that Leonard would be responsible for legal and title expenses at closing, amounting to about $1,000, which would cover the cost of the bank's lawyer. The bank's lawyer is responsible for certifying to the bank that the owner has a valid fee simple ownership in the property, which means that the owner has the right to dispose of it, pledge it, or pass it on to his heirs as he sees fit. Also, the lawyer ascertains that there are no liens on the property senior to the bank's interest. Unless the document's conditions specify otherwise, the seniority of a lien depends on the date it was recorded in the County Registry of Deeds Office. When a lien is paid off a discharge is put on record. There are some liens that are a matter of record that a bank will accept as senior to its position. These include zoning or use regulations, building codes, party wall agreements (where two buildings share the same wall) or certain easements where one party has specific rights or privileges on the land of the other. The certification of title is often done through the issuance of an insurance policy written by a title insurance company at a one-time cost paid by the borrower or purchaser. Harris also told him he should not rely on the bank's attorney to represent him. He should budget about $900 for his own attorney and other miscellaneous costs. Lastly, there would be a 1% loan origination fee of $2,100 payable to the bank upon closing.

Legal Advice

Leonard then consulted Josh Guberman, his family's attorney, about the whole transaction.

Leonard was very disturbed about the bank's requirement that he sign the mortgage note personally.

His attorney told him that he did not want to understate the risk, but that this was a customary bank practice in making small mortgage loans in Massachusetts, where banks were often more conservative than in other areas of the country.

Leonard inquired about alternate methods for raising the extra $30,000 besides accepting the new mortgage. Guberman believed that secondary financing could be obtained, but at an interest rate of 15% and only with a personal endorsement. The seller might take back a purchase money second mortgage, but again Leonard would probably have to sign the note personally and repay the entire loan over a 3- to 5-year period. In addition, if the demand for the property were as strong as Leonard indicated an all-cash offer might have a better chance of winning the property than one contingent upon a purchase money second mortgage.

Leonard asked whether he would not be taking a big risk in making an offer for the property without having his financing secured. Guberman explained that while he would have to submit a written offer for the property, together with a deposit to be held by the real estate broker, he could make his offer contingent upon his being permitted to assume the seller's mortgage. This would give him some safety, while still permitting him to attempt to find a higher mortgage.

If Leonard's offer were accepted, a purchase and sales contract would be signed, based on a standard Boston Real Estate Board form (see Exhibit 2). Guberman said that in case of forfeiture as a result of the buyer's failure to perform, the sales deposit, normally 5%-10% of the purchase price, would be kept by the seller as liquidated damages. Therefore, Leonard's risk would be limited to $8,400 if the seller would accept a 5% deposit. Also, if the seller could not deliver a quit-claim deed, relinquishing any interest he held in the property and giving a clear title to the buyer, the buyer would be entitled to a refund of his deposit.

Guberman then asked Leonard whether he had adequate funds to complete the project even with a $210,000 mortgage. The asking price for the property was $168,000; the remodeling cost $55,000; carrying costs during construction were now $13,500 because of the higher mortgage; closing costs $4,000; and escrow funds $1,000. These costs totalled $241,500. The $210,000 mortgage or mortgages and his $25,000 equity would still leave him $6,500 short. Leonard replied that he planned to save money by acting as his own general contractor, and he hoped to remodel and rent the property in four months rather than six months. A $210,000 first mortgage with an annual carrying charge of $24,300, although requiring a personal guarantee, would give him leverage, making the pretax return on his $25,000 cash investment 27.0% versus 13.1% on a free and clear or all-cash basis.

In addition, he would be amortizing a mortgage. The return would be even greater if he lived in the building and managed it himself.

Guberman asked why Leonard was not selling the units as condominiums. He should be able to get about $80,000 per unit, which could net him $60,000 for all four units after sales costs.

Moreover, at a later time a conversion might run into problems given the difficulties of evicting existing tenants. Leonard responded by saying that he wanted to maximize the long-term opportunity of what he considered an excellent market in an excellent area. He was not in it for a short term gain. Rents should increase over time. Although the 1986 tax law reduced the advantages of being able to depreciate real property, he expected that about $8,000 of his income from the property would be sheltered from taxes.

The lawyer said that Leonard's analysis seemed reasonable, but his estimates did not put a dollar value on Leonard's time. He wondered whether this should be considered. Also, he wanted Leonard to realize the seriousness of this time commitment since his full-time job was still his prime responsibility. Finally, he asked him to consider carefully the amount of the offer he was submitting and the risks involved.

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started