Question

May 10, 2022 NTSB/AIR-22-05 Collision into Terrain Safari Aviation Inc. Airbus AS350 B2, N985SA Kekaha, Hawaii December 26, 2019 Abstract: This report discusses the December

May 10, 2022 NTSB/AIR-22-05 Collision into Terrain Safari Aviation Inc. Airbus AS350 B2, N985SA Kekaha, Hawaii December 26, 2019 Abstract: This report discusses the December 26, 2019, accident involving a seven-seat helicopter operated by Safari Aviation Inc. as a commercial air tour flight that encountered instrument meteorological conditions and collided into terrain in a remote, wooded area near Kekaha, Hawaii, on the island of Kauai. The pilot and the six passengers were fatally injured, and the helicopter was destroyed. Safety issues identified in this report include limited ability of existing infrastructure to fully support some aviation safety-related functions needed for the safe operation of low-flying air tour flights, resulting in air tour pilots having to rely on their own in-flight visual weather assessments; absence of safety assurance processes to guide pilot decision-making; and ineffective monitoring and oversight of Hawaii air tour operators by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). As a result of this investigation, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) makes eight new safety recommendations to the FAA, one new safety recommendation to the Vertical Aviation Safety Team, and one new safety recommendation to tour flight operators. NTSB also reiterates nine previously issued recommendations and two previously issued classified recommendations to the FAA.

What Happened

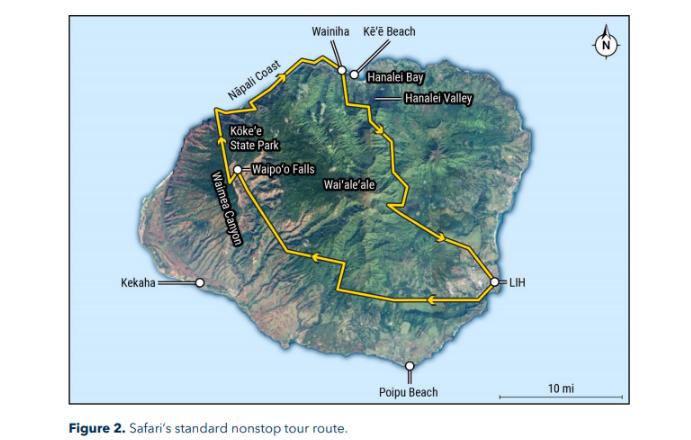

On December 26, 2019, about 1657 Hawaii standard time, a seven-seat helicopter operated by Safari Aviation Inc. as a commercial air tour flight encountered instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) and collided into terrain in a remote, wooded area near Kekaha, Hawaii, on the island of Kauai. The pilot and the six passengers were fatally injured, and the helicopter was destroyed. The weather on Kauai had been favorable for tours for most of the day; however, just before the accident flight departed, low clouds and rain began moving onshore from the northwest (which was an atypical weather pattern for Kauai) and affecting locations on the tour route, including areas where the accident flight was headed. At least three other tour pilots saw the adverse weather and decided to divert their tours away from it. The accident pilot, however, decided to continue his tour into deteriorating weather, eventually losing adequate visual references before the helicopter struck terrain.

What We Found

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) found that the mountainous terrain on Kauai and in other locations in Hawaii limits the ability of the existing infrastructure to fully support certain aviation safety-related functions, especially those needed for the safe operation of low-flying air tour flights. These limitations include sparse weather observation sources and terrain interference with air-to-ground radio communications and flight-tracking technology, which could be used by ground personnel to provide en route support to pilots. As a result of these limitations, air tour pilots in Hawaii rely heavily on their own in-flight visual weather assessments. Although Safari's company policy emphasized adherence to minimum visibility and altitude requirements, the company lacked a documented safety assurance process by which it could determine how effectively its pilots were assessing weather-related risks and adhering to company policy. For the accident pilot, his decision to continue the flight into deteriorating weather was likely influenced by a lack of relevant weather information and an atypical weather pattern, and it is possible that he inaccurately assessed the weather conditions in flight or was overconfident in his abilities

We also found that improvements in the level of oversight of Hawaii air tour operators provided by the Federal Aviation Administration's (FAA) local flight standards district office are needed to decrease the likelihood that operators and pilots will drift toward risky weather-related operating practices, which may have been occurring in the local air tour community. Further, although we recommended 15 years ago that the FAA develop and require cue-based weather training for Hawaii air tour pilots that specifically addresses hazardous aspects of local weather phenomena and in-flight decision-making, the FAA has not yet taken responsive action. As a result, the accident pilot did not receive the training we intended. Due, in part, to the accident helicopter's lack of flight-tracking equipment or flight data or image recorder, it was not possible for us to determine whether the pilot maintained control of the helicopter before it struck terrain. In addition, the accident helicopter (like most helicopters typically used for air tours) was not equipped with features designed to help a pilot maintain orientation and helicopter control in degraded visibility weather conditions. We determined that the probable cause of this accident was the pilot's decision to continue flight under visual flight rules (VFR) into IMC, which resulted in the collision into terrain. Contributing to the accident was Safari Aviation Inc.'s lack of safety management processes to identify hazards and mitigate the risks associated with factors that influence pilots to continue VFR flight into IMC. Also contributing to the accident was the FAA's delayed implementation of a Hawaii aviation weather camera program, its lack of leadership in the development of a cue-based weather training program for Hawaii air tour pilots, and its ineffective monitoring and oversight of Hawaii air tour operators' weather-related operating practices.

What We Recommended

As a result of this investigation, NTSB made safety recommendations to the FAA regarding infrastructure improvements in Hawaii that can enable continuous radio communications and flight position tracking, improvements to the FAA's surveillance of Hawaii air tour operations, and requirements for Hawaii air tour operators to equip their fleets with flight tracking capabilities and to provide active flight monitoring by trained company flight support personnel. We also made safety recommendations to the FAA to take actions that can help all air tour operators and pilots prevent a drift toward risky weather-related operating practices. These actions include developing and distributing guidance on how to scale an effective safety management system (SMS) and encouraging operators to perform routine reviews of onboard video recordings and flight tracking data. We also recommended that the FAA and helicopter industry and air tour safety groups encourage the voluntary adoption of helicopter safety technologies designed to help prevent accidents resulting from inadvertent encounters with IMC. In addition, we reiterated our previously issued safety recommendations to the FAA related to installing aviation weather cameras in Hawaii, training ground support specialists to effectively use imagery from those cameras when providing weather briefings to pilots, developing and requiring cue-based training for Hawaii air tour pilots, and requiring operators to implement flight data monitoring programs and SMS. We also reiterated our previously issued safety recommendations to the FAA related to requiring the installation of crash-resistant flight recorder systems in aircraft like the accident helicopter; requiring air tour operators to install onboard equipment that enables traffic-alerting, flight tracking, and other safety-related services; and developing and requiring the use of simulation technologies in pilot training programs to help prevent accidents involving inadvertent encounters with IMC.

Based on information provided by several local tour pilots, the weather on Kauai was favorable for tours for most of the day, but low clouds and rain began moving onshore from the northwest and affecting that side of the island about the time that the accident flight departed. Two pilots for another helicopter tour operator (referred to as "Company 1" in this report) diverted their tours away from Waimea Canyon (located in northwest Kauai) about 1629 to avoid the adverse weather they saw in that area. (See section 1.4.2 for more information about the weather conditions during the other tours.) Limited information was available about the accident helicopter's flight track. A series of air traffic control (ATC) radar returns showed that a VFR aircraft departed LIH at the time of the accident flight's departure and proceeded south then west and northwest before the returns ceased about 1639 at the expected limits of the radar coverage for low-flying aircraft in that area. 4 Presuming the accident pilot followed the standard tour route as expected, the flight would have continued northwest and north to the Nāpali Coast as part of a clockwise loop around the island

A pilot for another helicopter tour operator (referred to as "Company 2" in this report) estimated that his tour was about 5 minutes behind the accident flight when he heard the accident pilot transmit "upper mic" over the radio. The Company 2 pilot said that, upon hearing the accident pilot's transmission, he could see adverse weather at the north end of Waimea Canyon but presumed that, because the accident flight had continued, there must have been a way through the weather. The Company 2 pilot decided to continue his tour to see whether he could also go that way. Onboard video from this pilot's tour showed that, about 1654, his helicopter was flying in good visibility with an area of visible moisture ahead (see Figure 4), and he told his passengers that the next site would be Waimea Canyon. 8 The video showed

The Company 2 pilot's tour exited the canyon near the upper microwave tower site about 1658. This pilot continued the tour for about 2 minutes but found that the weather (which included reduced visibility and rain) "wasn't as good as [he] thought it would be." He decided to reverse course and divert the tour (rather than continue north to the Nāpali Coast). (See section 1.4.2 for more information about the Company 2 pilot's tour.) A witness who was hiking along the Nuʻalolo Trail (located north of Waimea Canyon) said that heavy rain had fallen there between about 1600 and 1645. He said he was on a ridgeline near the trail's 2-mile marker when he first heard a helicopter about 1645 or 1650. Trail elevation at the witness's location was about 3,100 ft mean sea level (msl). He said very dense fog was present, and he heard the helicopter for about 30 to 50 seconds but didn't see it. He said the helicopter sounded like it was hovering above and beside him, then it sounded like it was turning or moving across the sky. He next heard a strange squealing noise then could no longer hear the helicopter. He ran along the trail to look for the helicopter but never saw it, noting that the fog was so dense he could see only about 20 ft in front of him. The accident flight was expected back at LIH about 1720. According to Safari's president, who also owned the company and served as its director of operations (DO) at the time of the accident, a Safari employee (who was performing flight-locating duties) notified him about 1731 that the flight was overdue, and company flight locating procedures began. The other Safari pilot flying that day had completed his tours but returned to his helicopter about 1800 after he was notified that the accident flight was overdue. He said he departed LIH shortly thereafter, observed adverse weather to the north, and felt certain that the accident pilot had landed his helicopter somewhere to wait it out. The Safari pilot remained south of the weather, climbed his helicopter (to increase radio range), and made several radio calls to try to locate the accident flight but was unsuccessful. The next morning at 0932, a rescue helicopter team spotted the wreckage in wooded, mountainous terrain in Kōkeʻe State Park at an elevation of about 3,000 ft msl. (See section 1.6). The accident site was about 0.5 nautical mile (nm) east of the standard tour route and about 0.27 nm southwest of where the witness on the Nuʻalolo Trail was standing when he heard the helicopter noise stop.

Findings

None of the following safety issues were identified for the accident flight: (1) pilot qualification deficiencies or impairment due to medical condition, alcohol, other drugs, or fatigue; (2) helicopter malfunction or failure; or (3) pressure on the pilot from other Safari Aviation Inc. managers to complete the flight. 2. The accident pilot continued the tour flight into an area of deteriorating weather until he encountered instrument meteorological conditions and lost adequate visual references. 3. Due to the lack of information about the helicopter's flight track or any other parameters, it could not be determined whether the accident pilot maintained controlled flight after encountering instrument meteorological conditions or lost control of the helicopter before it struck terrain. 4. The pilot's decision to continue the flight into deteriorating visibility was likely influenced by a lack of relevant weather information and an atypical weather pattern and may have been influenced by the possibilities that he inadequately assessed the weather conditions in flight or was overconfident in his abilities. 5. Considering that at least three other tour flights entered reduced visibility conditions on the day of the accident, it is possible that procedural drift toward risky weather-related operating practices existed among pilots of the local air tour community. 6. As a result of the Federal Aviation Administration's (FAA) lack of leadership and expert guidance in developing cue-based weather training for air tour operators in Hawaii, Safari Aviation Inc.'s pilot training program, which was approved by the Honolulu flight standards district office, did not provide Safari's pilots with the type of training that the FAA's cue-based training research determined was effective for improving pilots' skills for accurately assessing and avoiding hazardous in-flight weather conditions. 7. Although Safari Aviation Inc. had a policy that defined company expectations for pilot adherence to minimum weather requirements, it did Aviation Investigation Report NTSB/AIR-22-05 94 not have adequate safety assurance processes to assess whether company strategies to reduce pilots' risk of inadvertent encounters with instrument meteorological conditions were effective. 8. The Federal Aviation Administration's full implementation of a Hawaii weather camera system as planned will provide access to continuously updated weather imagery that will support pilots' weather-avoidance decision-making and likely reduce weather-related air tour accidents in the state. 9. Now that the first aviation weather cameras are operational in Hawaii, the ability for en route pilots to obtain essential information from ground support personnel, such as flight service station specialists, based on the cameras' imagery is particularly relevant due to the rapidly changing weather conditions on the islands. 10. Improved air-to-ground radio communications capability between the pilots of low-flying air tour flights in Hawaii and ground support personnel, such as flight service station specialists and company flight support personnel, can enhance the safety of air tour operations. 11. The automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast (ADS-B) infrastructure in Hawaii is insufficient to adequately enable ADS-B Out- and In-supported services, such as real-time flight position tracking and onboard traffic advisories, that are essential for the safety of low-flying air tour aircraft throughout their entire tour routes. 12. Air tour pilots would benefit from real-time decision-making support from trained company flight support personnel who have operational control authority, continuous access to updated weather information, and the ability to actively monitor the progress of the flights and communicate with pilots en route. 13. The safety of all air tour operations, regardless of size, would be enhanced by the implementation of a safety management system. 14. A flight data monitoring program, which can enable an operator to identify and mitigate factors that may influence pilots' deviations from safe operating procedures, can be particularly beneficial for operators like Safari Aviation Inc. that conduct single-pilot operations and have little opportunity to directly observe their pilots. Aviation Investigation Report NTSB/AIR-22-05 95 15. The recording and routine review of onboard videos and automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast data by air tour operators, ideally as part of a safety management system with an integrated flight data monitoring program, could enable them to 1) identify instances where their pilots encountered reduced-visibility weather conditions or descended below Federal Aviation Administration-required minimum altitudes, 2) perform nonpunitive examinations of these events to determine whether they resulted from encounters or near encounters with instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) and to learn about IMC-related hazards, and 3) evaluate the effectiveness of existing risk controls to prevent their pilots from drifting into risky weather-related operating practices. 16. The use of technologies and innovative approaches can help the Honolulu flight standards district office provide increased oversight of Hawaii air tour operating practices, which could decrease the likelihood of a drift toward risky operating practices by local air tour operators and their pilots; these approaches may include but are not limited to comparing automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast flight position data from air tour flights with weather camera imagery for the route and periodically reviewing onboard video recordings to monitor pilots' weather-related decisionmaking during tours. 17. If all commercial air tour aircraft were required to be equipped with crash-resistant recording systems that capture images, flight deck audio, and flight data, improved information about accident circumstances would permit more definitive evaluation of the causes of fatal air tour accidents and identification of more effective measures to prevent these accidents. 18. Although Airbus Helicopters had developed and issued service bulletins for the voluntary retrofit of recording systems on Airbus AS350 helicopters more than 2 years before the accident, Safari Aviation Inc. had not installed such recorders in the accident helicopter or any other helicopter in its fleet. 19. Increased voluntary adoption of helicopter safety technologies designed to help reduce accidents resulting from inadvertent encounters with instrument meteorological conditions can help save lives. 20. The use of simulation technologies in helicopter pilot training has the potential to help reduce accidents involving inadvertent encounters with instrument meteorological conditions by enhancing the weather-related decision-making and assessment aspect of scenario-based training and Aviation Investigation Report NTSB/AIR-22-05 96 providing opportunities for pilots to develop skills to detect and recover from vestibular illusions that could lead to spatial disorientation

Probable Cause

The NTSB determines that the probable cause of this accident was the pilot's decision to continue flight under visual flight rules (VFR) into instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), which resulted in the collision into terrain. Contributing to the accident was Safari Aviation Inc.'s lack of safety management processes to identify hazards and mitigate the risks associated with factors that influence pilots to continue VFR flight into IMC. Also contributing to the accident was the Federal Aviation Administration's delayed implementation of a Hawaii aviation weather camera program, its lack of leadership in the development of a cue-based weather training program for Hawaii air tour pilots, and its ineffective monitoring and oversight of Hawaii air tour operators' weather-related operating practices.

QUESTIONS:

- How airport and aircraft familiarity (or lack thereof!) may have influenced the effectiveness of the emergency response

- How effectively the SAR function was integrated into the emergency response to locate survivors of the accident

- Specific problems/challenges and possible improvements

Kekaha Waimea Canyon Napali Coast Kke'e State Park Wainiha Ke' Beach Waipo'o Falls Hanalei Bay Wai'ale ale Figure 2. Safari's standard nonstop tour route. Hanalei Valley Poipu Beach LIH 10 mi

Step by Step Solution

3.28 Rating (154 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Introduction In the aftermath of the tragic helicopter accident involving Safari Aviation Inc in Kekaha Hawaii on December 26 2019 understanding the effectiveness of the emergency response particularl...

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started