Question

Merrill Lynch developed a strategy to convince MoGen, Inc. to place their convertible bond issue through them. MoGen will raise capital through the issuance of

Merrill Lynch developed a strategy to convince MoGen, Inc. to place their convertible bond issue through them. MoGen will raise capital through the issuance of Convertible Bonds. In this assignment you are to critique the financial strategy developed by the underwriter, Merrill Lynch. Be certain to consider the marketing of the issue, cost of the issue, and the pricing of the bonds in your evaluation of Merrill Lynchs strategy

MoGen Inc.

On January 10, 2006, the managing director of Merrill Lynchs Equity-Linked Capital Markets Group, Dar Maanavi, was reviewing the final drafts of a proposal for a convertible debt offering by MoGen, Inc. As a leading biotechnology company in the United States, MoGen had become an important client for Merrill Lynch over the years. In fact, if this deal were to be approved by MoGen at $5 billion, it would represent Merrill Lynchs third financing for MoGen in four years with proceeds raised totaling $10 billion. Moreover, this convert would be the largest such single offering in history. The proceeds were earmarked to fund a variety of capital expenditures, research and development (R&D) expenses, working capital needs, as well as a share repurchase program. The Merrill Lynch team had been working with MoGens senior management to find the right tradeoff between the conversion feature and the coupon rate for the bond. Maanavi knew from experience that there was no free lunch, when structuring the pricing of a convertible. Issuing companies wanted the conversion price to be as high as possible and the coupon rate to be as low as possible; whereas investors wanted the opposite: a low conversion price and a high coupon rate. Thus, the challenge was to structure the convert to make it attractive to the issuing company in terms of its cost of capital, while at the same time selling for full price in the market. Maanavi was confident that the right balance in the terms of the convert could be found, and he was also confident that the convert would serve MoGens financing needs better than a straight bond or equity issuance. But, he needed to make a decision about the final terms of the issue in the next few hours, as the meeting with MoGen was scheduled for early the next morning.

Company History

Founded in 1985 as MoGen (Molecular Genetics) the company was among the first in the biotechnology industry to deliver on the commercial promises of emerging sciences, such as recombinant DNA and molecular biology. After years of research, MoGen emerged with two of the first biologically derived human therapeutic drugs, RENGEN and MENGEN, both of which helped to offset the damaging effects from chemotherapy for cancer patients undergoing treatment. Those two MoGen products were among the first blockbuster drugs to emerge from the nascent biotechnology industry.

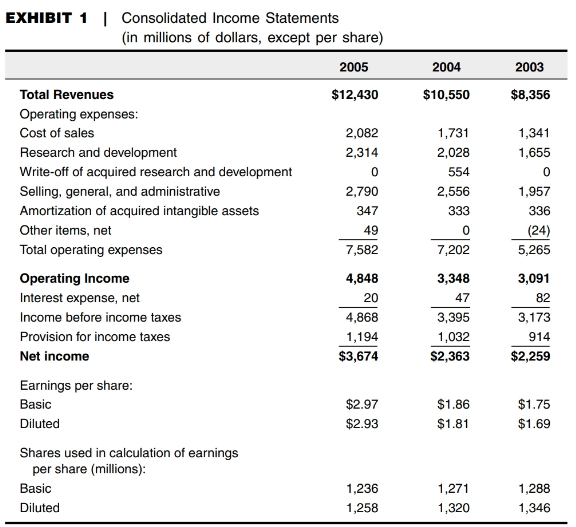

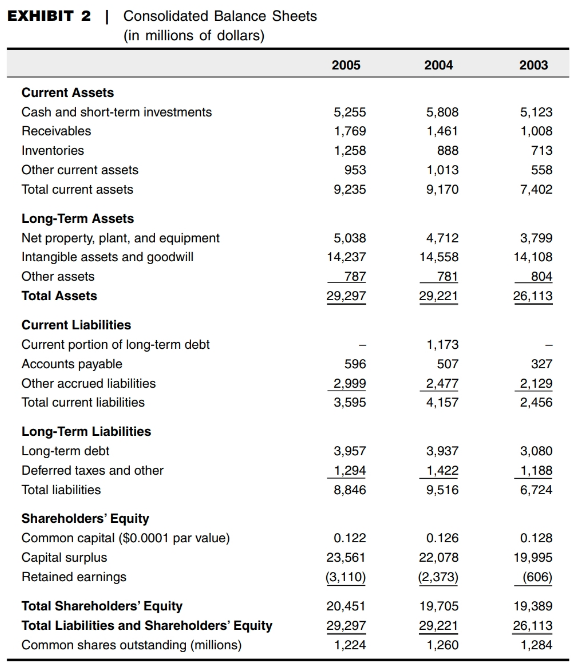

By 2006, MoGen was one of the leading biotech companies in an industry that included firms such as Genentech, Amgen, Gilead Sciences, Celgene, and Genzyme. The keys to success for all biotech companies were finding new drugs through research and then getting the drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). MoGens strategy for drug development was to determine the best mode for attacking a patients issue and then focusing on creating solutions via that mode. Under that approach, MoGen had been able to produce drugs with the highest likelihood of both successfully treating the patient as well as making the company a competitive leader in drug quality. In January 2006, MoGens extensive R&D expenditures had resulted in a portfolio of five core products that focused on supportive cancer care. The success of that portfolio had been strong enough to offset other R&D write-offs so that MoGen was able to report $3.7 billion in profits in 2005 on $12.4 billion in sales. Sales had grown at an annual rate of 29% over the previous five years, and earnings per share had improved to $2.93 for 2005, compared with $1.81 and $1.69 for 2004 and 2003, respectively (Exhibits 1 and 2).

The FDA served as the regulating authority to safeguard the public from dangerous drugs and required extensive testing before it would allow a drug to enter the U.S. marketplace. The multiple hurdles and long lead-times required by the FDA created a constant tension with the biotech firms who wanted quick approval to maximize the return on their large investments in R&D. Moreover, there was always the risk that a drug would not be approved or that after it was approved, it would be pulled from the market due to unexpected adverse reactions by patients. Over the years, the industry had made progress in shortening the approval time and improving the predictability of the approval process. At the same time, industry R&D expenditures had increased 12.6% over 2003 in the continuing race to find the next big break- through product.

Like all biotech companies, MoGen faced uncertainty regarding new product creation as well as challenges involved with sustaining a pipeline of future products. Now a competitive threat of follow-on biologics or biosimilars began emerging. As drugs neared the end of their patent protection, competitors would produce similar drugs as substitutes. Competitors could not produce the drug exactly, because they did not have access to the original manufacturers molecular clone or purification process. Thus, biosimilars required their own approval to ensure they performed as safely as the original drugs. For MoGen, this threat was particularly significant in Europe, where several patents were approaching expiration.

Funding Needs

MoGen needed to ensure a consistent supply of cash to fund R&D and to maintain financial flexibility in the face of uncertain challenges and opportunities. MoGen had cited several key areas that would require approximately $10 billion in funding for 2006:

1. Expanding manufacturing and formulation, and fill and finish capacity: Recently, the company had not been able to scale up production to match increases in demand for certain core products. The reason for the problem was that MoGen outsourced most of its formulation and fill and finish manufacturing processes, and these off- shore companies had not been able to expand their operations quickly enough. Therefore, MoGen wanted to remove such supply risks by increasing both its internal manufacturing capacity in its two existing facilities in Puerto Rico as well as new construction in Ireland. These projects represented a majority of MoGens total capital expenditures that were projected to exceed $1 billion in 2006.

2. Expanding investment in R&D and late-stage trials: Late-stage trials were particularly expensive, but were also critical as they represented the last big hurdle before a drug could be approved by the FDA. With 11 late-stage mega-site trials expected to commence in 2006, management knew that successful outcomes were critical for MoGens ability to maintain momentum behind its new drug development pipeline. The trials would likely cost $500 million. MoGen had also decided to diversify its product line by significantly increasing R&D to approximately $3 billion for 2006, which was an increase of 30% over 2005.

3. Acquisition and licensing: MoGen had completed several acquisition and licensing deals that had helped it achieve the strong growth in revenues and earnings per share (EPS). The company expected to continue this strategy and had projected to complete a purchase of Genix, Inc., in 2006 for approximately $2 billion in cash. This acquisition was designed to help MoGen capitalize on Genixs expertise in the discovery, development, and manufacture of human therapeutic antibodies.

4. The stock repurchase program: Due to the highly uncertain nature of its operations, MoGen had never issued dividends to shareholders but instead had chosen to pursue a stock repurchase program. Senior management felt that this demonstrated a strong belief in the companys future and was an effective way to return cash to shareholders without being held to the expectation of having a regular dividend payout. Due to strong operational and financial performance over the past several years, MoGen had executed several billion dollars worth of stock repurchases, and it was managements intent to continue repurchases over the next few years. In 2005, MoGen purchased a total of 63.2 million shares for an aggregate $4.4 billion.1 As of December 31, 2005, MoGen had $6.5 billion remaining in the authorized share repurchase plan, of which management expected to spend $3.5 billion in 2006.

With internally generated sources of funds expected to be $5 billion (net income plus depreciation), MoGen would fall well below the $10 billion expected uses of funds for 2006. Thus, management estimated that an offering size of about $5 billion would cover MoGens needs for the coming year.

Convertible Debt

A convertible bond was considered a hybrid security, because it had attributes of both debt and equity. From an investors point of view, a convert provided the safety of a bond plus the upside potential of equity. The safety came from receiving a fixed income stream in the form of the bonds coupon payments plus the return of principal. The upside potential came from the ability to convert the bond into shares of common stock. Thus, if the stock price should rise above the conversion price, the investor could convert and receive more than the principal amount. Because of the potential to realize capital appreciation via the conversion feature, a converts coupon rate was always set lower than what the issuing company would pay for straight debt. Thus, when investors bought a convertible bond, they received less income than from a comparable straight bond, but they gained the chance of receiving more than the face value if the bonds conversion value exceeded the face value.

To illustrate, consider a convertible bond issued by BIO, Inc., with a face value of $1,000 and a maturity of five years. Assume that the convert carries a coupon rate of 4% and a conversion price of $50 per share and that BIOs stock was selling for $37.50 per share at the time of issuance. The coupon payment gives an investor $40 per year in interest (4% ?? $1,000), and the conversion feature gives investors the opportunity to exchange the bond for 20 shares (underlying shares) of BIOs common stock ($1,000 ?? $50). Because BIOs stock was selling at $37.50 at issuance, the stock price would need to appreciate by 33% (conversion premium) to reach the conversion price of $50. For example, if BIOs stock price were to appreciate to $60 per share, investors could convert each bond into 20 shares to realize the bonds conversion value of $1,200. On the other hand, if BIOs stock price failed to reach $50 within the five-year life of the bond, the investors would not convert, but rather would choose to receive the bonds $1,000 face value in cash.

Because the conversion feature represented a right, rather than an obligation, investors would postpone conversion as long as possible even if the bond was well in the money. Suppose, for example, that after three years BIOs stock had risen to $60. Investors would then be holding a bond with a conversion value of $1,200; which is to say, if converted they would receive the 20 underlying shares worth $60 each. With two years left until maturity, however, investors would find that they could realize a higher value by selling the bond on the open market, rather than converting it. For example, the bond might be selling for $1,250; $50 higher than the conversion value. Such a premium over conversion value is typical, because the market recognizes that convertibles have unlimited upside potential, but protected downside. Unlike owning BIO stock directly, the price of the convertible bond cannot fall lower than its bond valuethe value of the coupon payments and principal paymentbut its conversion value could rise as high as the stock price will take it. Thus, as long as more upside potential is possible, the premium price will exist, and investors will have the incentive to sell their bonds, rather than convert them prior to maturity.

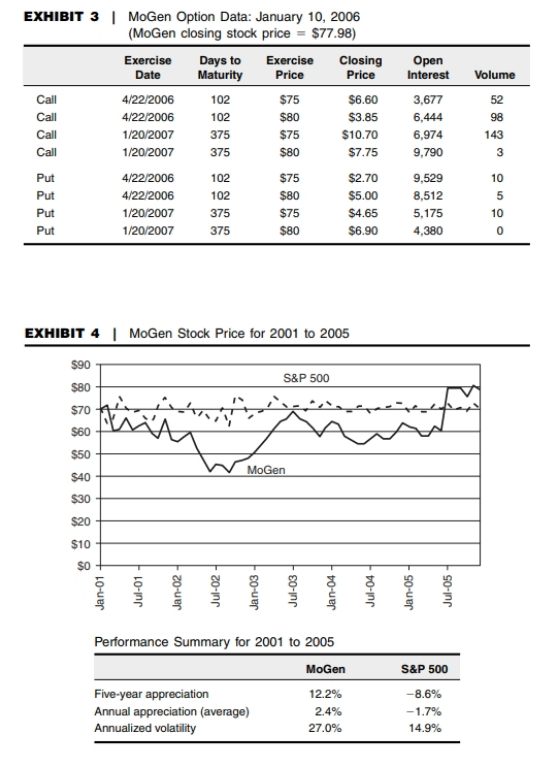

Academics modeled the value of a convertible as the sum of the straight bond value plus the value of the conversion feature. This was equivalent to valuing a convert as a bond plus a call option or a warrant. Although MoGen did not have any warrants outstanding, there was an active market in MoGen options (Exhibit 3). Over the past five years, MoGens stock price had experienced modest appreciation with considerable variation (Exhibit 4).

MoGens Financial Strategy

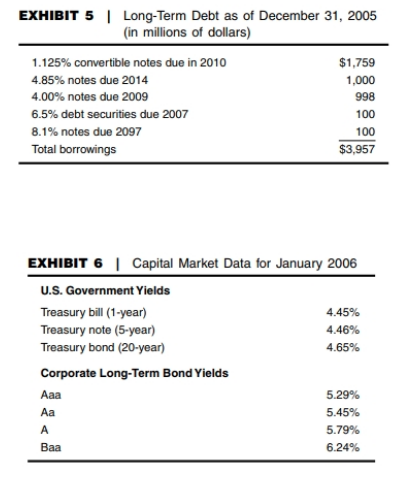

As of December 31, 2005, the company had approximately $4 billion of long-term debt on the books (Exhibit 5). About $2 billion of the debt was in the form of straight debt with the remaining $1.8 billion as seven-year convertible notes. The combination of industry and company-specific risks had led MoGen to keep its long-term debt at or below 20% of total capitalization. There was a common belief that because of the industry risks, credit-rating agencies tended to penalize biotech firms by placing a ceiling on their credit ratings. MoGens relatively low leverage, however, allowed it to command a Standard and Poors (S&P) rating of A??, which was the highest rating within the industry. Based on discussions with S&P, MoGen management was confident that the company would be able to maintain its rating for the $5 billion new straight debt or convertible issuance. For the current market conditions, Merrill Lynch had estimated a cost to MoGen of 5.75%, if it issued straight five-year bonds. (See Exhibit 6 for capital market data.)

MoGens seven-year convertible notes had been issued in 2003 and carried a con- version price of $90.000 per share. Because the stock price was currently at $77.98 per share, the bondholders had not yet had the opportunity to exercise the conversion option.3 Thus, the convertibles had proven to be a low-cost funding source for MoGen, as it was paying a coupon of only 1.125%. If the stock price continued to remain below the conversion price, the issue would not be converted and MoGen would simply retire the bonds in 2010 (or earlier, if called) at an all-in annual cost of 1.125%.

On the other hand, if the stock price appreciated substantially by 2010, then the bond- holders would convert and MoGen would need to issue 11.1 shares per bond out- standing or approximately 20 million new shares. Issuing the shares would not necessarily be a bad outcome, because it would amount to issuing shares at $90 rather than at $61, the stock price at the time of issuance.

Since its initial public offering (IPO), MoGen had avoided issuing new equity, except for the small amounts of new shares issued each year as part of managements incentive compensation plan. The addition of these shares had been more than offset, however, by MoGens share repurchase program, so that shares outstanding had fallen from 1,280 million in 2004, to 1,224 million in 2005. Repurchasing shares served two purposes for MoGen: (1) It had a favorable impact upon EPS by reducing the shares outstanding; and (2) It served as a method for distributing cash to shareholders. Although MoGen could pay dividends, management preferred the flexibility of repurchasing shares. If MoGen were to institute a dividend, there was always the risk that the dividend might need to be decreased or eliminated during hard times which, when announced, would likely result in a significant drop of the stock price.

Merrill Lynch Equity-Linked Origination Team

The U.S. Equity-Linked Origination Team was part of Merrill Lynchs Equity Capital Markets Division that resided in the Investment Banking Division. The team was the product group that focused on convertible, corporate derivative, and special equity transaction origination for Merrill Lynchs U.S. corporate clients. As product experts, members worked with the industry bankers to educate clients on the benefits of utilizing equity-linked instruments. They also worked closely with derivatives and convertible traders, the equity and equity-linked sales teams, and institutional investors including hedge funds, to determine the market demand for various strategies and securities. Members had a high level of expertise in tax, accounting, and legal issues. The technical aspects of equity-linked securities were rigorous, requiring significant financial modeling skills, including the use of option pricing models, such as Black- Scholes and other proprietary versions of the model used to price convertible bonds. Within the equities division and investment banking, the team was considered one of the most technically capable and had proven to be among the most profitable businesses at Merrill Lynch.

Pricing Decision

Dar Maanavi was excited by the prospect that Merrill Lynch would be the lead book runner of the largest convertible offering in history. At $5 billion, MoGens issue would represent more than 12% of the total proceeds for convertible debt in the United States during 2005. Although the convert market was quite liquid and the Merrill Lynch team was confident that the issue would be well received, the unprecedented

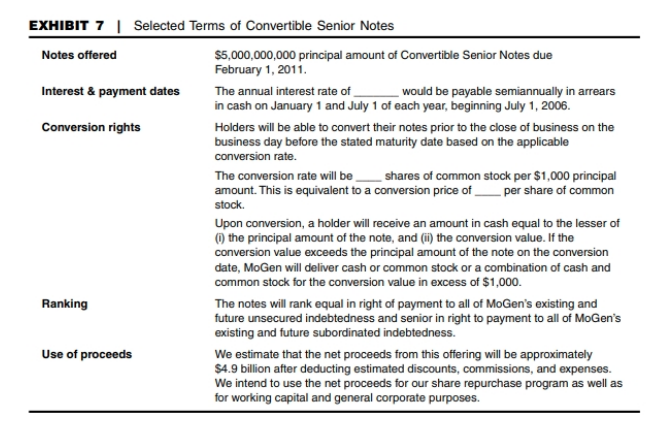

size heightened the need to make it as marketable as possible. Maanavi knew that MoGen wanted a maturity of five years, but was less certain as to what he should propose regarding the conversion premium and coupon rate. These two terms needed to be satisfactory to MoGens senior management team while at the same time being attractive to potential investors in the marketplace. Exhibit 7 shows the terms of the offering that had already been determined.

Most convertibles carried conversion premiums in the range of 10% to 40%. The coupon rates for a convertible depended upon many factors, including the conversion premium, maturity, credit rating, and the markets perception of the volatility of the issuing companys stock. Issuing companies wanted low coupon rates and high con- version premiums, whereas investors wanted the opposite: high coupons and low con- version premiums. Companies liked a high conversion premium, because it effectively set the price at which its shares would be issued in the future. For example, if MoGens bond was issued with a conversion price of $109, it would represent a 40% conversion premium over its current stock price of $77.98. Thus, if the issue were eventually converted, the number of MoGen shares issued would be 40% less than what MoGen would have issued at the current stock price. Of course, a high conversion premium also carried with it a lower probability that the stock would ever reach the conversion price. To compensate investors for this reduced upside potential, MoGen would need to offer a higher coupon rate. Thus, the challenge for Maanavi was to find the right combination of conversion premium and coupon rate that would be acceptable to MoGen management as well as desirable to investors.

There were two types of investor groups for convertibles: fundamental investors and hedge funds. Fundamental investors liked convertibles, because they viewed them as a safer form of equity investment. Hedge fund investors viewed convertibles as an opportunity to engage in an arbitrage trading strategy that typically involved holding long positions of the convertible and short positions of the common stock. Companies preferred to have fundamental investors, because they took a longer-term view of their investment than hedge funds. If the conversion premium was set above 40%, fundamental investors tended to lose interest because the convertible became a more speculative investment with less upside potential. Thus, if the conversion premium were set at 40% or higher, it could be necessary to offer an abnormally high coupon rate for a convertible. In either case, Maanavi thought a high conversion premium was not appropriate for such a large offering. It could work for a smaller, more volatile stock, but not for MoGen and not for a $5 billion offering.

Early in his conversations with MoGen, Maanavi had discussed the accounting treatment required for convertibles. Recently, most convertibles were being structured to use the treasury stock method, which was desirable because it reduced the impact upon the reported fully diluted EPS. To qualify for the treasury stock method the convertible needed to be structured as a net settled security. This meant that investors would always receive cash for the principal amount of $1,000 per bond, but could receive either cash or shares for the excess over $1,000 upon conversion. The alternative method of accounting was the if-converted method, which would require MoGen to compute fully diluted EPS, as if investors received shares for the full amount of the bond when they converted; which is to say the new shares equaled the principal amount divided by the conversion price per share. The treasury stock method, however, would allow MoGen to report far fewer fully diluted shares for EPS purposes because it only included shares representing the excess of the bonds con- version value over the principal amount. Because much of the issues proceeds would be used to fund the stock repurchase program, MoGens management felt that using the treasury stock method would be a better representation to the market of MoGens likely EPS, and therefore agreed to structure the issue accordingly (see conversion rights in Exhibit 7).

In light of MoGen managements objectives, Maanavi decided to propose a con- version premium of 25%, which was equivalent to conversion price of $97.000.6 MoGen management would appreciate that the conversion premium would appeal to a broad segment of the market, which was important for a $5 billion offering. On the other hand, Maanavi knew that management would be disappointed that the conversion premium was not higher. Management felt that the stock was selling at a depressed price and represented an excellent buy. In fact, part of the rationale for having the stock repurchase program was to take advantage of the stock price being low. Maanavi suspected that management would express concern that a 25% premium would be sending a bad signal to the market: a low conversion premium could be interpreted as managements lack of confidence in the upside potential of the stock. For a five-year issue, the stock would only need to rise by 5% per year to reach the conversion price by maturity. If management truly believed the stock had strong appreciation potential, then the conversion premium should be set much higher.

If Maanavi could convince MoGen to accept the 25% conversion premium, then choosing the coupon rate was the last piece of the pricing puzzle to solve. Because he was proposing a mid-range conversion premium, investors would be satisfied with a modest coupon. Based on MoGens bond rating, the company would be able to issue straight five-year bonds with a 5.75% yield. Therefore, Maanavi knew that the convertible should carry a coupon rate noticeably lower than 5.75%. The challenge was to estimate the coupon rate that would result in the debt being issued at exactly the face value of $1000 per bond.

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started