MIPS, java

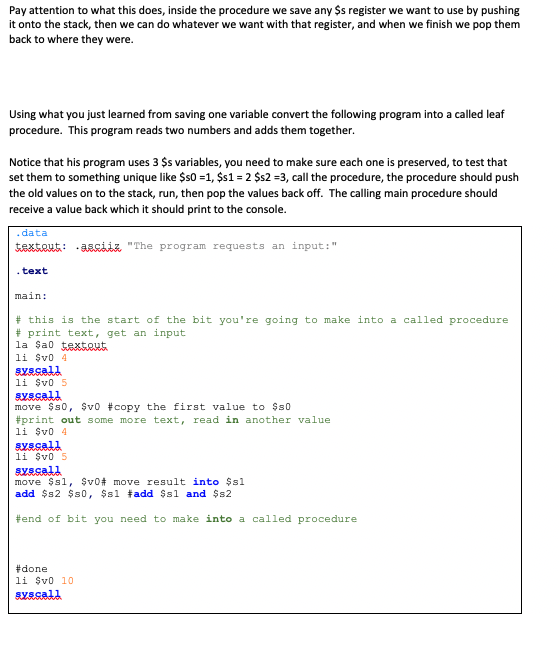

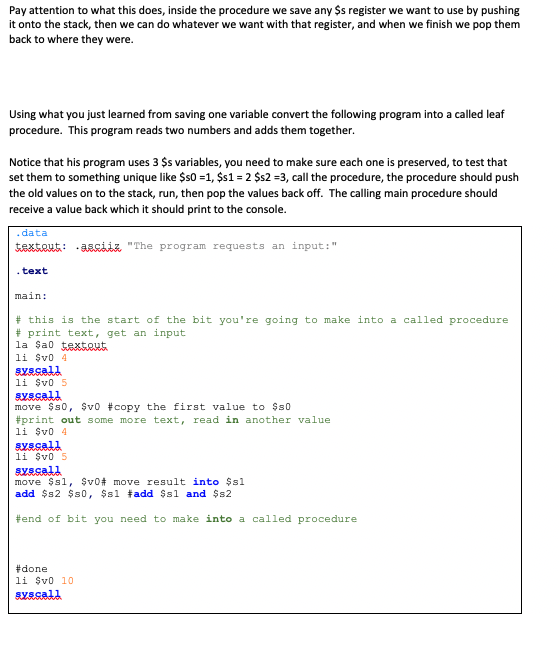

- Make the relevant portion above into a called procedure. This relevant portion reads in two values ($s0 and $s1), and adds them up ($s2). So this procedure needs to push $s0, $s1 and $s2 onto the stack, read in two values, add them up, and then restore those $s0, $s1, and $s2 back to their original values).

To store values you need to get the stack pointer, then use sw to store the word

To restore values you need to get the stack pointer, and load the value, in the correct order, into the right location

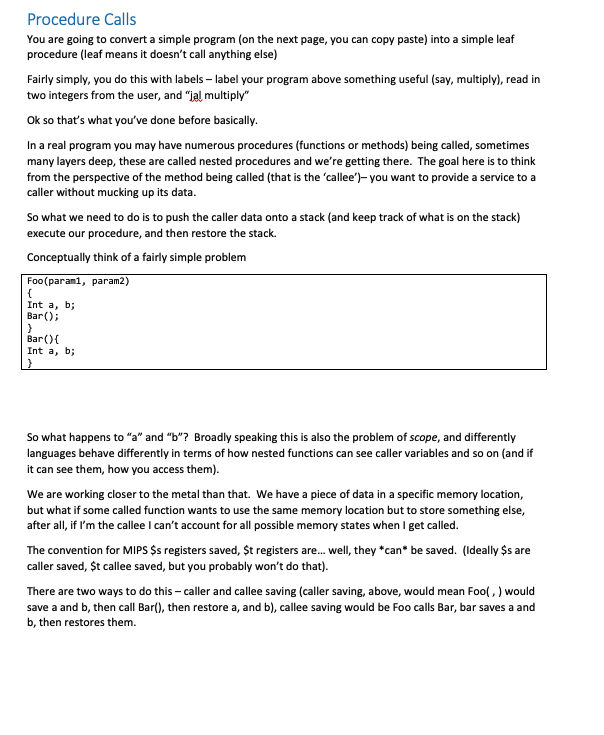

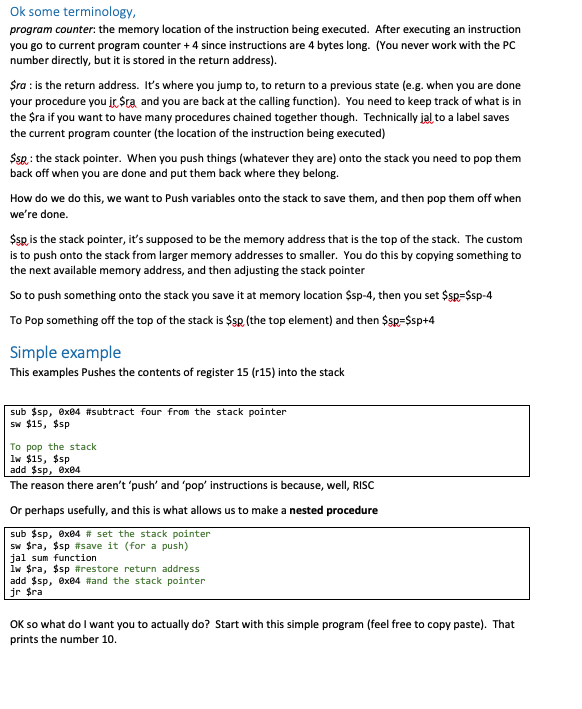

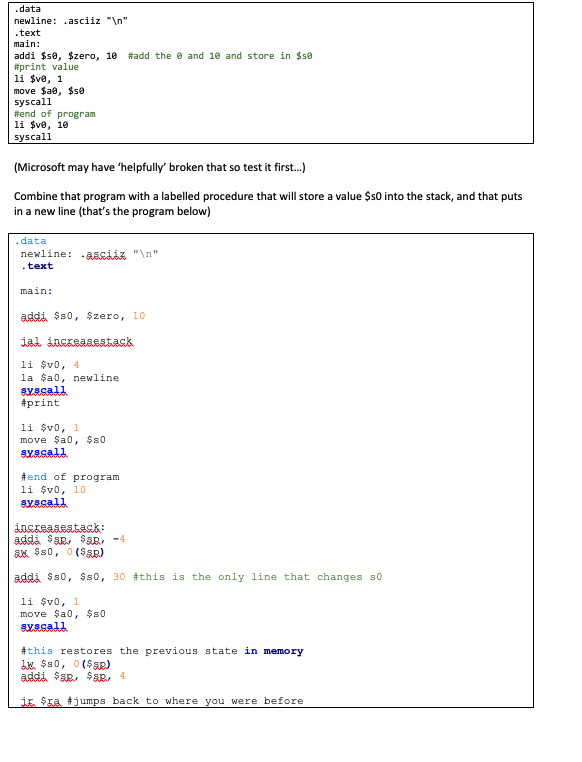

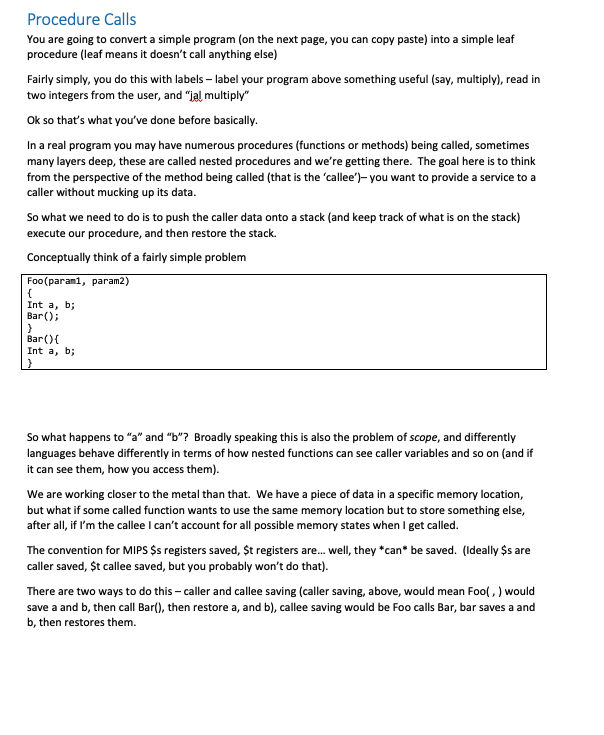

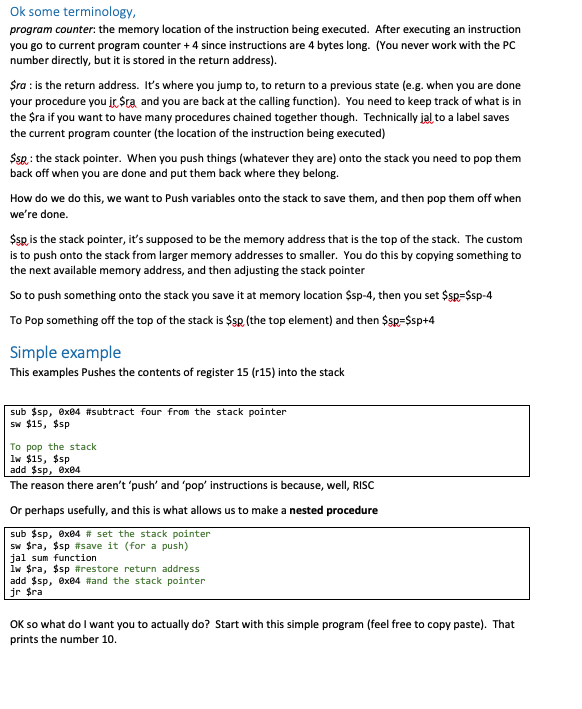

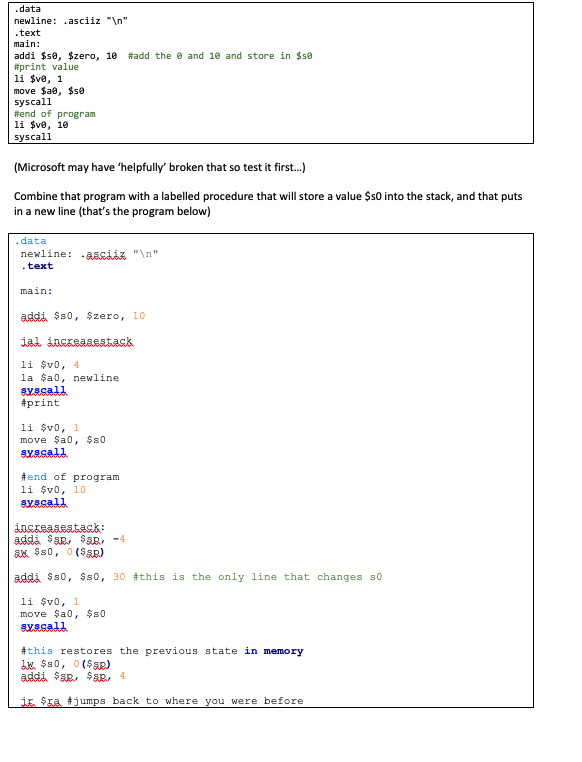

Procedure Calls You are going to convert a simple program (on the next page, you can copy paste) into a simple leaf procedure (leaf means it doesn't call anything else) Fairly simply, you do this with labels label your program above something useful (say, multiply), read in two integers from the user, and "jal multiply" Ok so that's what you've done before basically. In a real program you may have numerous procedures (functions or methods) being called, sometimes many layers deep, these are called nested procedures and we're getting there. The goal here is to think from the perspective of the method being called (that is the 'callee')- you want to provide a service to a caller without mucking up its data. So what we need to do is to push the caller data onto a stack (and keep track of what is on the stack) execute our procedure, and then restore the stack. Conceptually think of a fairly simple problem Foo (param1, param2) { Int a, b; Bar(); } Bar() { Int a, b; } So what happens to "a" and "b"? Broadly speaking this is also the problem of scope, and differently languages behave differently in terms of how nested functions can see caller variables and so on (and if it can see them, how you access them). We are working closer to the metal than that. We have a piece of data in a specific memory location, but what if some called function wants to use the same memory location but to store something else, after all, if I'm the callee I can't account for all possible memory states when I get called. The convention for MIPS $s registers saved, St registers are... well, they can be saved. (Ideally $s are caller saved, $t callee saved, but you probably won't do that). There are two ways to do this - caller and callee saving (caller saving, above, would mean Foo(,) would save a and b, then call Bar(), then restore a, and b), callee saving would be Foo calls Bar, bar saves a and b, then restores them. Ok some terminology, program counter the memory location of the instruction being executed. After executing an instruction you go to current program counter + 4 since instructions are 4 bytes long. (You never work with the PC number directly, but it is stored in the return address). $ra: is the return address. It's where you jump to, to return to a previous state (e.g. when you are done your procedure you ic Sra and you are back at the calling function). You need to keep track of what is in the $ra if you want to have many procedures chained together though. Technically jal to a label saves the current program counter (the location of the instruction being executed) $sp: the stack pointer. When you push things (whatever they are) onto the stack you need to pop them back off when you are done and put them back where they belong. How do we do this, we want to Push variables onto the stack to save them, and then pop them off when we're done. $sp, is the stack pointer, it's supposed to be the memory address that is the top of the stack. The custom is to push onto the stack from larger memory addresses to smaller. You do this by copying something to the next available memory address, and then adjusting the stack pointer So to push something onto the stack you save it at memory location $sp-4, then you set $sp=$sp-4 To Pop something off the top of the stack is $sp (the top element) and then $sp=$sp+4 Simple example This examples Pushes the contents of register 15 (r15) into the stack sub $sp, x64 #subtract four from the stack pointer sw $15, $sp To pop the stack lw $15, $sp add $sp, x64 The reason there aren't 'push' and 'pop' instructions is because, well, RISC Or perhaps usefully, and this is what allows us to make a nested procedure sub $sp, 6x04 # set the stack pointer sw $ra, $sp #save it (for a push) jal sum function iw $ra, $sp #restore return address add $sp, exe4 #and the stack pointer jr fra OK so what do I want you to actually do? Start with this simple program (feel free to copy paste). That prints the number 10. .data newline: .asciiz " " .text main: addi $se, $zero, 10 #add the @ and 10 and store in $se #print value li $va, 1 move $ae, $se syscall #end of program li $ve, 10 syscall (Microsoft may have 'helpfully' broken that so test it first...) Combine that program with a labelled procedure that will store a value $s into the stack, and that puts in a new line (that's the program below) .data newline: asciiz " " .text main: addi $80, $zero, 10 jat increascatask. li $v0, 4 la $a0, newline syssall #print li $v0, 1 move $a0, $80 syssali #end of program li $v0, 10 syssada increasestask: addi. SSR, SSR-4 sw $80, (SR) addi $50, $50, 30 #this is the only line that changes so li $v0, 1 move $a0, $80 syasall #this restores the previous state in memory Iw $50, ($) addi. $sp,$sp,4 ir $58. #jumps back to where you were before Pay attention to what this does, inside the procedure we save any $s register we want to use by pushing it onto the stack, then we can do whatever we want with that register, and when we finish we pop them back to where they were Using what you just learned from saving one variable convert the following program into a called leaf procedure. This program reads two numbers and adds them together. Notice that his program uses 3 $s variables, you need to make sure each one is preserved, to test that set them to something unique like $50 =1, $s1 = 2 $s2 =3, call the procedure, the procedure should push the old values on to the stack, run, then pop the values back off. The calling main procedure should receive a value back which it should print to the console. .data texteut: asciiz "The program requests an input." .text main: # this is the start of the bit you're going to make into a called procedure # print text, get an input la Sal textout li $v0 4 syssala li $v0 5 syssall move $so, $vo #copy the first value to $50 #print out some more text, read in another value li $v0 4 syssall li $v05 syssalt move $si, $v0# move result into $81 add $s2 $50, $sl #add $sl and $s2 #end of bit you need to make into a called procedure #done li $v0 10 syscall Procedure Calls You are going to convert a simple program (on the next page, you can copy paste) into a simple leaf procedure (leaf means it doesn't call anything else) Fairly simply, you do this with labels label your program above something useful (say, multiply), read in two integers from the user, and "jal multiply" Ok so that's what you've done before basically. In a real program you may have numerous procedures (functions or methods) being called, sometimes many layers deep, these are called nested procedures and we're getting there. The goal here is to think from the perspective of the method being called (that is the 'callee')- you want to provide a service to a caller without mucking up its data. So what we need to do is to push the caller data onto a stack (and keep track of what is on the stack) execute our procedure, and then restore the stack. Conceptually think of a fairly simple problem Foo (param1, param2) { Int a, b; Bar(); } Bar() { Int a, b; } So what happens to "a" and "b"? Broadly speaking this is also the problem of scope, and differently languages behave differently in terms of how nested functions can see caller variables and so on (and if it can see them, how you access them). We are working closer to the metal than that. We have a piece of data in a specific memory location, but what if some called function wants to use the same memory location but to store something else, after all, if I'm the callee I can't account for all possible memory states when I get called. The convention for MIPS $s registers saved, St registers are... well, they can be saved. (Ideally $s are caller saved, $t callee saved, but you probably won't do that). There are two ways to do this - caller and callee saving (caller saving, above, would mean Foo(,) would save a and b, then call Bar(), then restore a, and b), callee saving would be Foo calls Bar, bar saves a and b, then restores them. Ok some terminology, program counter the memory location of the instruction being executed. After executing an instruction you go to current program counter + 4 since instructions are 4 bytes long. (You never work with the PC number directly, but it is stored in the return address). $ra: is the return address. It's where you jump to, to return to a previous state (e.g. when you are done your procedure you ic Sra and you are back at the calling function). You need to keep track of what is in the $ra if you want to have many procedures chained together though. Technically jal to a label saves the current program counter (the location of the instruction being executed) $sp: the stack pointer. When you push things (whatever they are) onto the stack you need to pop them back off when you are done and put them back where they belong. How do we do this, we want to Push variables onto the stack to save them, and then pop them off when we're done. $sp, is the stack pointer, it's supposed to be the memory address that is the top of the stack. The custom is to push onto the stack from larger memory addresses to smaller. You do this by copying something to the next available memory address, and then adjusting the stack pointer So to push something onto the stack you save it at memory location $sp-4, then you set $sp=$sp-4 To Pop something off the top of the stack is $sp (the top element) and then $sp=$sp+4 Simple example This examples Pushes the contents of register 15 (r15) into the stack sub $sp, x64 #subtract four from the stack pointer sw $15, $sp To pop the stack lw $15, $sp add $sp, x64 The reason there aren't 'push' and 'pop' instructions is because, well, RISC Or perhaps usefully, and this is what allows us to make a nested procedure sub $sp, 6x04 # set the stack pointer sw $ra, $sp #save it (for a push) jal sum function iw $ra, $sp #restore return address add $sp, exe4 #and the stack pointer jr fra OK so what do I want you to actually do? Start with this simple program (feel free to copy paste). That prints the number 10. .data newline: .asciiz " " .text main: addi $se, $zero, 10 #add the @ and 10 and store in $se #print value li $va, 1 move $ae, $se syscall #end of program li $ve, 10 syscall (Microsoft may have 'helpfully' broken that so test it first...) Combine that program with a labelled procedure that will store a value $s into the stack, and that puts in a new line (that's the program below) .data newline: asciiz " " .text main: addi $80, $zero, 10 jat increascatask. li $v0, 4 la $a0, newline syssall #print li $v0, 1 move $a0, $80 syssali #end of program li $v0, 10 syssada increasestask: addi. SSR, SSR-4 sw $80, (SR) addi $50, $50, 30 #this is the only line that changes so li $v0, 1 move $a0, $80 syasall #this restores the previous state in memory Iw $50, ($) addi. $sp,$sp,4 ir $58. #jumps back to where you were before Pay attention to what this does, inside the procedure we save any $s register we want to use by pushing it onto the stack, then we can do whatever we want with that register, and when we finish we pop them back to where they were Using what you just learned from saving one variable convert the following program into a called leaf procedure. This program reads two numbers and adds them together. Notice that his program uses 3 $s variables, you need to make sure each one is preserved, to test that set them to something unique like $50 =1, $s1 = 2 $s2 =3, call the procedure, the procedure should push the old values on to the stack, run, then pop the values back off. The calling main procedure should receive a value back which it should print to the console. .data texteut: asciiz "The program requests an input." .text main: # this is the start of the bit you're going to make into a called procedure # print text, get an input la Sal textout li $v0 4 syssala li $v0 5 syssall move $so, $vo #copy the first value to $50 #print out some more text, read in another value li $v0 4 syssall li $v05 syssalt move $si, $v0# move result into $81 add $s2 $50, $sl #add $sl and $s2 #end of bit you need to make into a called procedure #done li $v0 10 syscall