Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

NEEDED: - NPV and IRR for each process. - Recommendation to the CFO and explain MINI-CASE Vegetron's CFO Calls Again (The first episode of this

NEEDED:

- NPV and IRR for each process.

- Recommendation to the CFO and explain

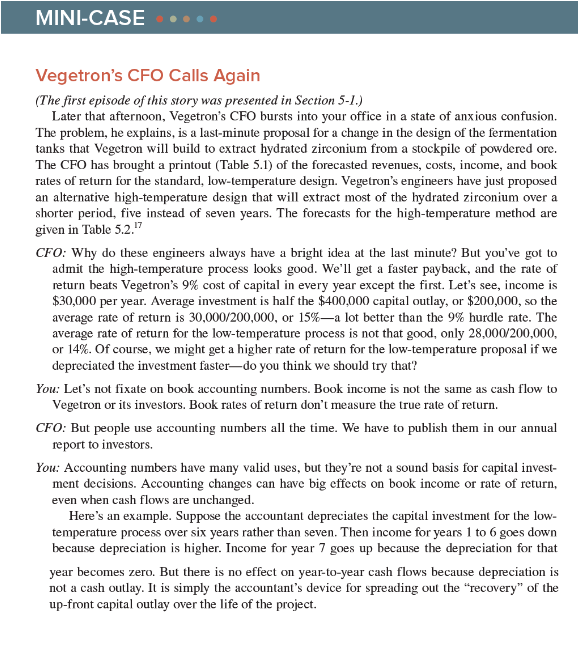

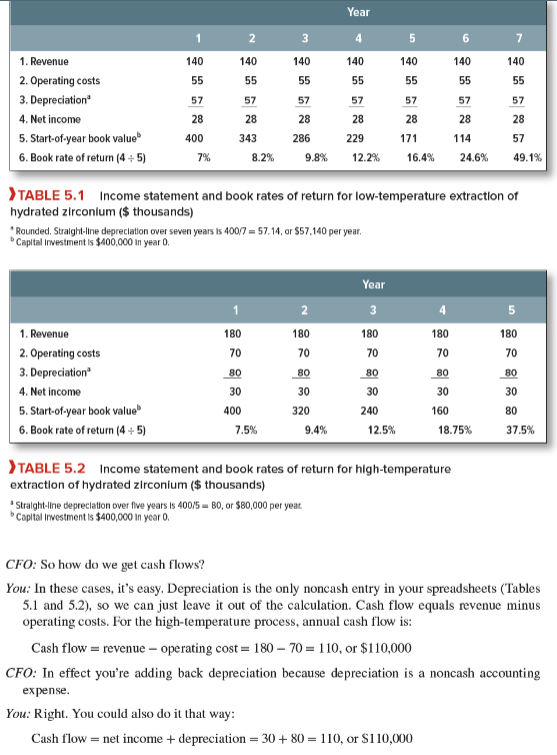

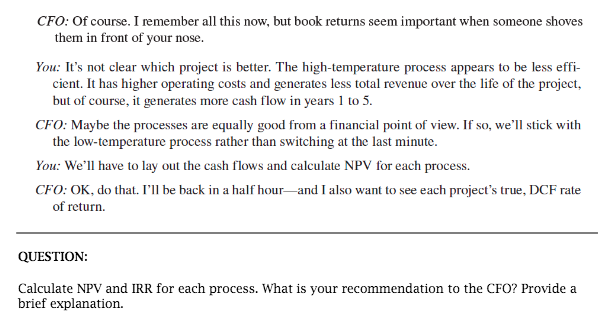

MINI-CASE Vegetron's CFO Calls Again (The first episode of this story was presented in Section 5-1.) Later that afternoon, Vegetron's CFO bursts into your office in a state of anxious confusion. The problem, he explains, is a last-minute proposal for a change in the design of the fermentation tanks that Vegetron will build to extract hydrated zirconium from a stockpile of powdered ore. The CFO has brought a printout (Table 5.1) of the forecasted revenues, costs, income, and book rates of return for the standard, low-temperature design. Vegetron's engineers have just proposed an alternative high-temperature design that will extract most of the hydrated zirconium over a shorter period, five instead of seven years. The forecasts for the high-temperature method are given in Table 5.2.17 CFO: Why do these engineers always have a bright idea at the last minute? But you've got to admit the high-temperature process looks good. We'll get a faster payback, and the rate of return beats Vegetron's 9% cost of capital in every year except the first. Let's see, income is $30,000 per year. Average investment is half the $400,000 capital outlay, or $200,000, so the average rate of return is 30,000/200,000, or 15%a lot better than the 9% hurdle rate. The average rate of return for the low-temperature process is not that good, only 28,000/200,000, or 14%. Of course, we might get a higher rate of return for the low-temperature proposal if we depreciated the investment faster, do you think we should try that? You: Let's not fixate on book accounting numbers. Book income is not the same as cash flow to Vegetron or its investors. Book rates of return don't measure the true rate of return. CFO: But people use accounting numbers all the time. We have to publish them in our annual report to investors. You: Accounting numbers have many valid uses, but they're not a sound basis for capital invest- ment decisions. Accounting changes can have big effects on book income or rate of return, even when cash flows are unchanged. Here's an example. Suppose the accountant depreciates the capital investment for the low- temperature process over six years rather than seven. Then income for years 1 to 6 goes down because depreciation is higher. Income for year 7 goes up because the depreciation for that year becomes zero. But there is no effect on year-to-year cash flows because depreciation is not a cash outlay. It is simply the accountant's device for spreading out the recovery" of the up-front capital outlay over the life of the project. Year 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1. Revenue 140 140 140 140 140 140 140 55 55 55 55 55 55 55 57 57 57 57 57 57 57 2. Operating costs 3. Depreciation 4. Net income 5. Start-of-year book value 6. Book rate of return (4-5) 28 28 28 28 28 28 400 7% 28 286 9.8% 229 114 343 8.2% 57 171 16.4% 12.2% 24.6% 49.1% > TABLE 5.1 Income statement and book rates of return for low-temperature extraction of hydrated zirconium ($ thousands) Rounded, Straight-line depreciation over seven years Is 400/7 = 57.14, or $57,140 per year, Capital investment is $400,000 in year O. 2 5 180 70 180 Year 3 180 70 80 180 180 70 70 70 80 80 80 80 1. Revenue 2. Operating costs 3. Depreciation 4. Net income 5. Start-of-year book value 6. Book rate of return (4+5) 30 30 30 30 30 400 7.5% 320 240 160 80 9.4% 12.5% 18.75% 37.5% > TABLE 5.2 Income statement and book rates of return for high-temperature extraction of hydrated zirconium ($ thousands) Straight-line depreciation over five years is 400/5 = BO, or $80,000 per year Capital Investment is $400,000 in year o CFO: So how do we get cash flows? You: In these cases, it's easy. Depreciation is the only noncash entry in your spreadsheets (Tables 5.1 and 5.2), so we can just leave it out of the calculation. Cash flow equals revenue minus operating costs. For the high-temperature process, annual cash flow is: Cash flow = revenue - operating cost = 180 - 70 = 110, or $110,000 CFO: In effect you're adding back depreciation because depreciation is a noncash accounting expense. You: Right. You could also do it that way: Cash flow = net income + depreciation = 30 + 80 = 110, or $110,000 CFO: Of course. I remember all this now, but book returns seem important when someone shoves them in front of your nose. You: It's not clear which project is better. The high-temperature process appears to be less effi- cient. It has higher operating costs and generates less total revenue over the life of the project, but of course, it generates more cash flow in years 1 to 5. CFO: Maybe the processes are equally good from a financial point of view. If so, we'll stick with the low-temperature process rather than switching at the last minute. You: We'll have to lay out the cash flows and calculate NPV for each process. CFO: OK, do that. I'll be back in a half hour and I also want to see each project's true, DCF rate of return. QUESTION: Calculate NPV and IRR for each process. What is your recommendation to the CFO? Provide a brief explanation

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started