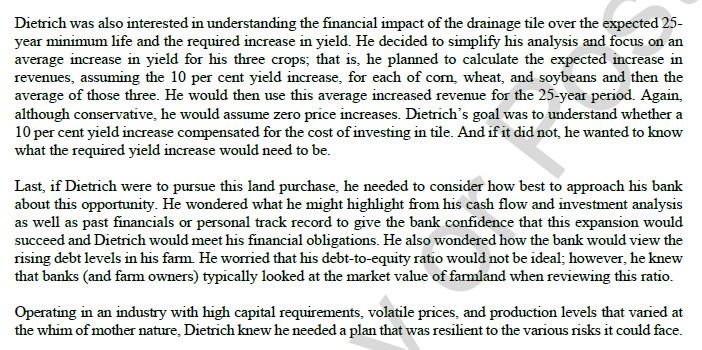

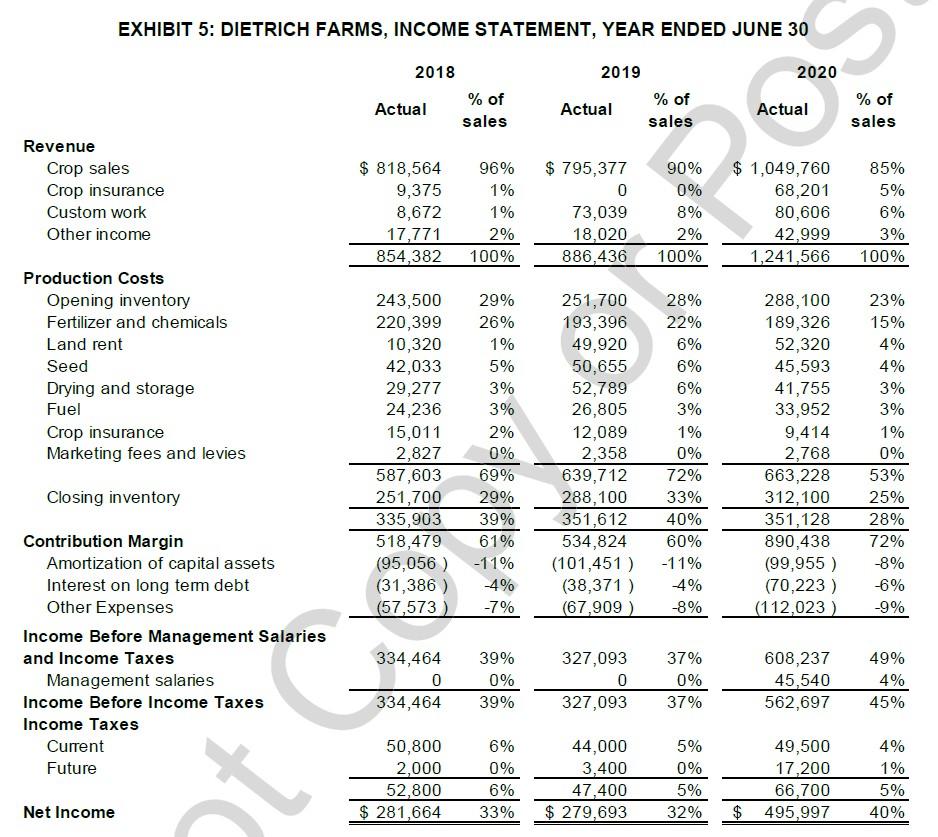

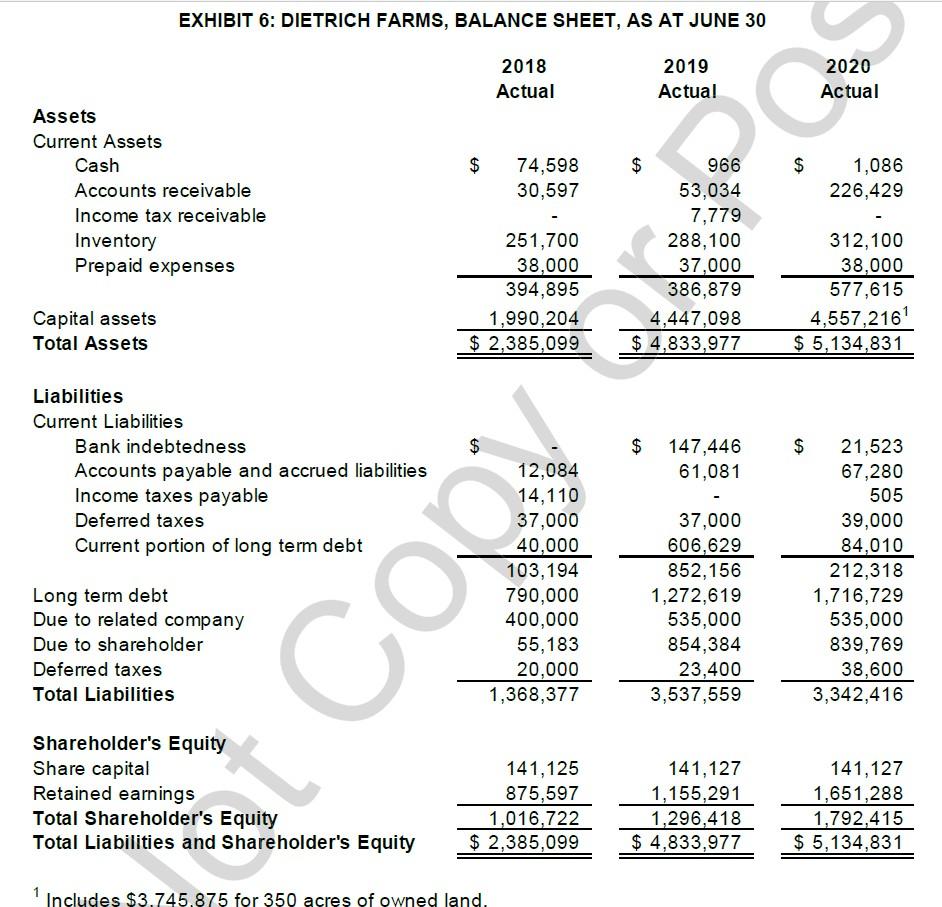

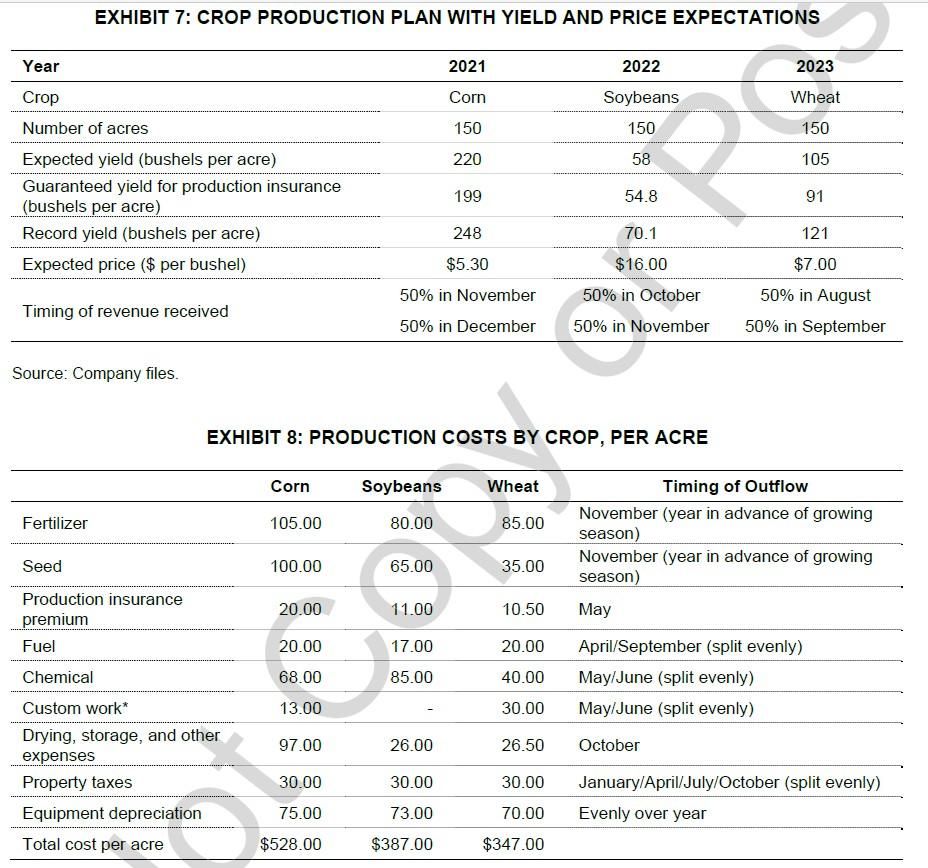

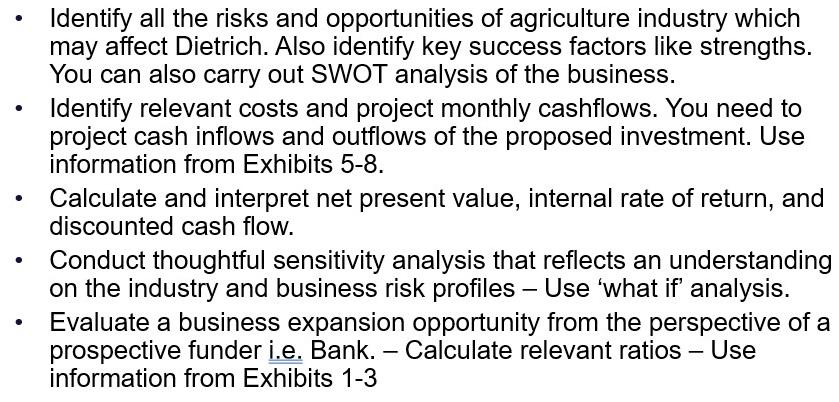

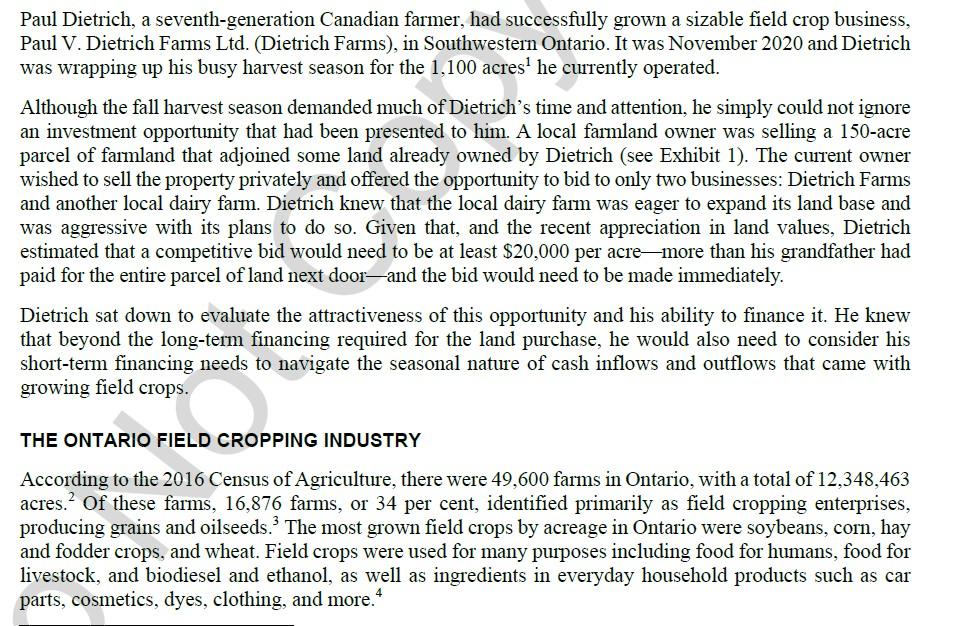

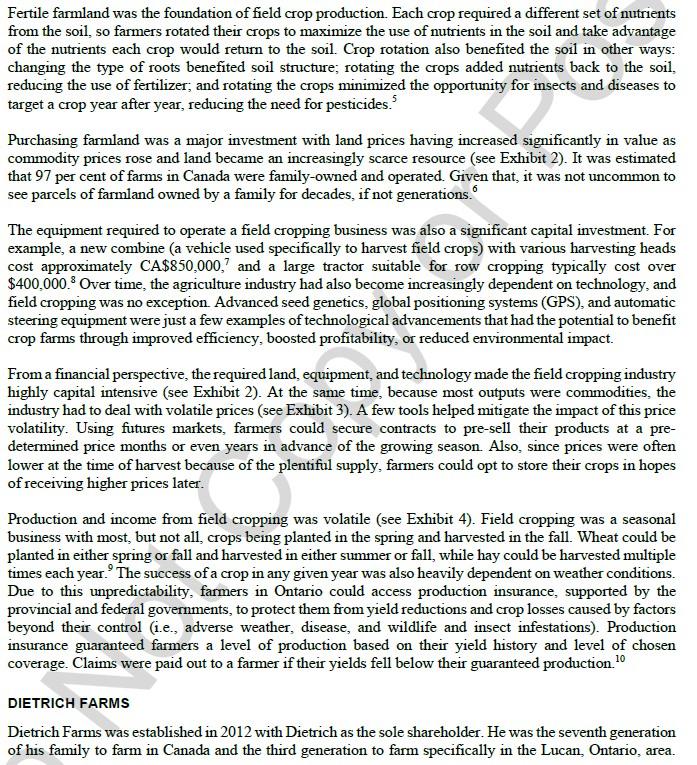

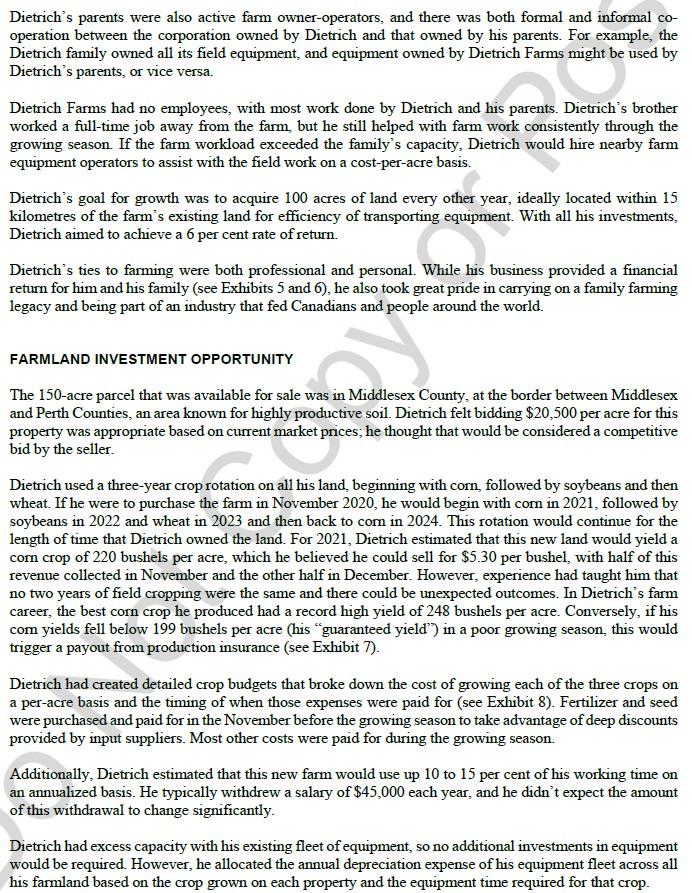

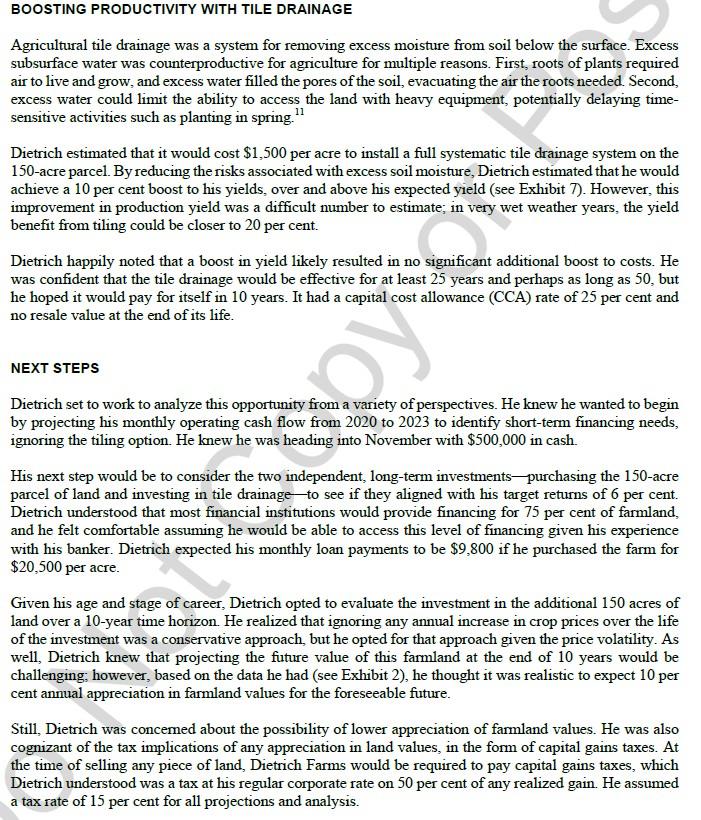

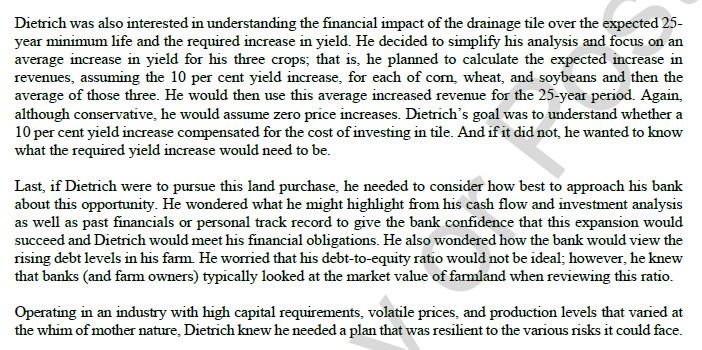

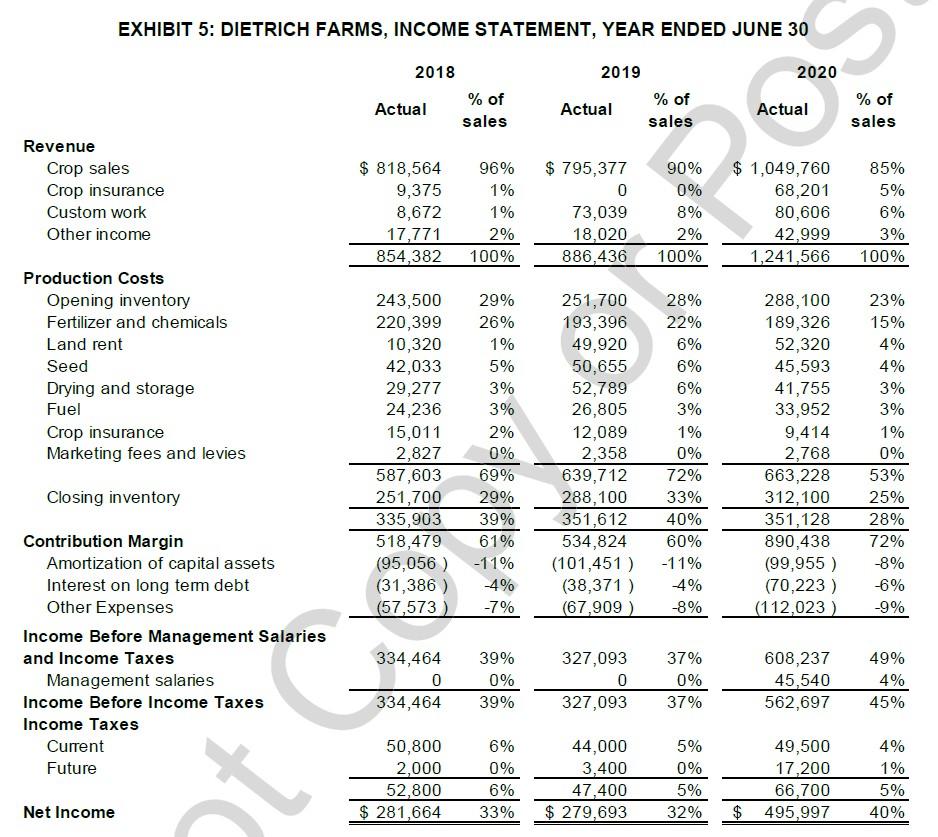

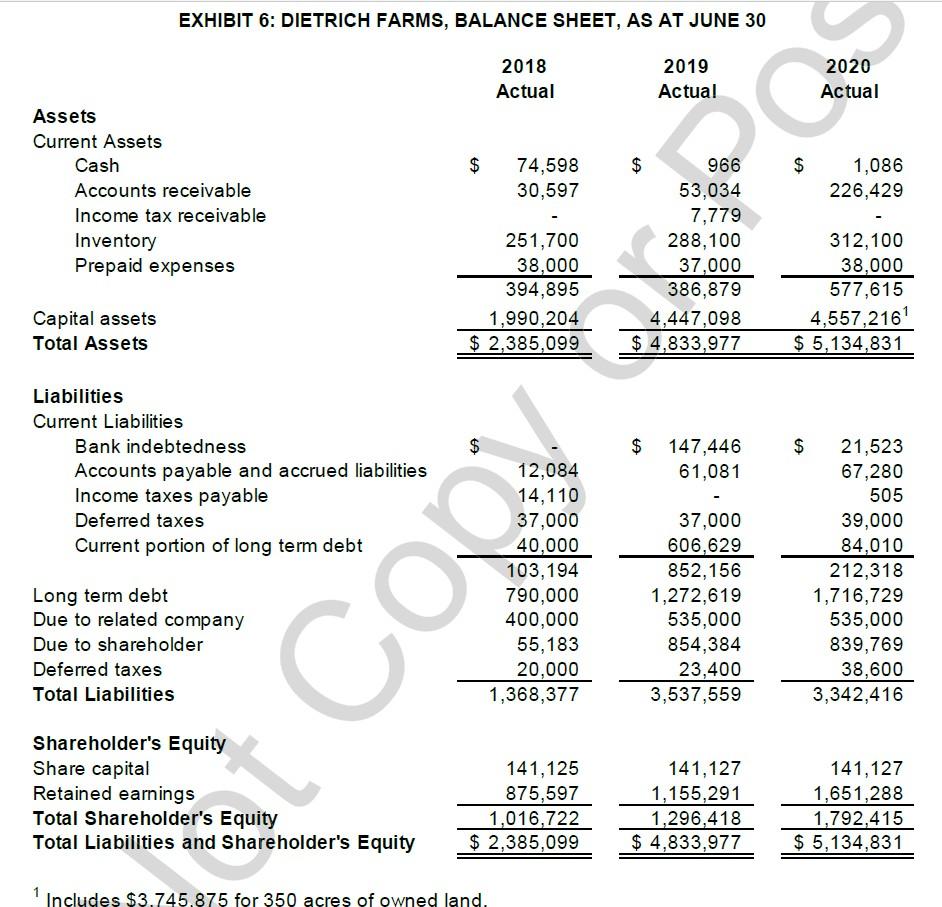

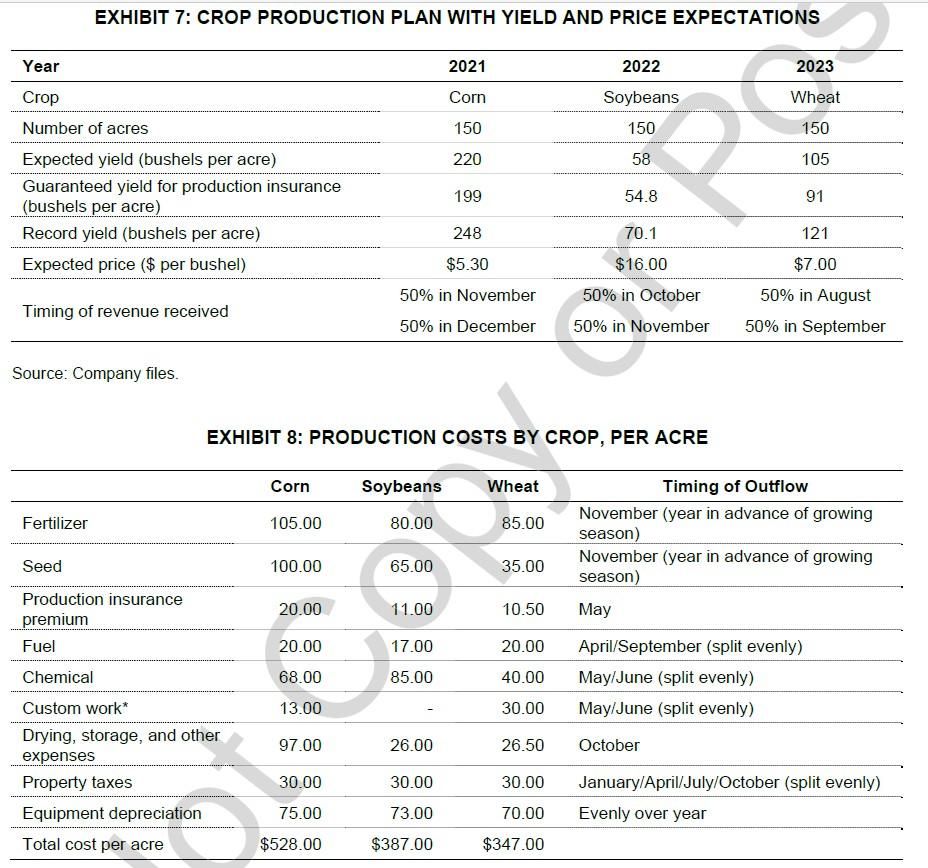

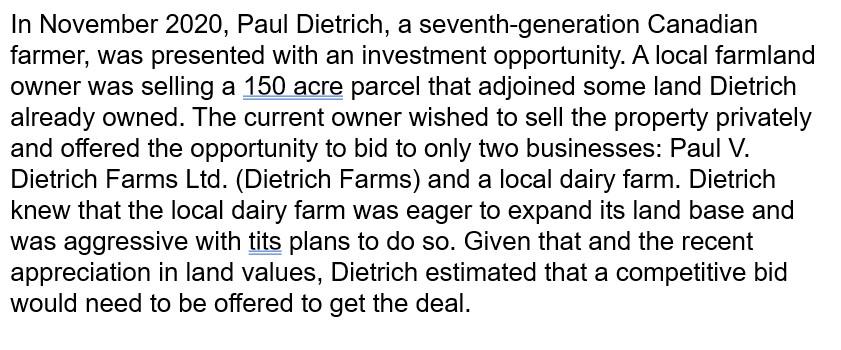

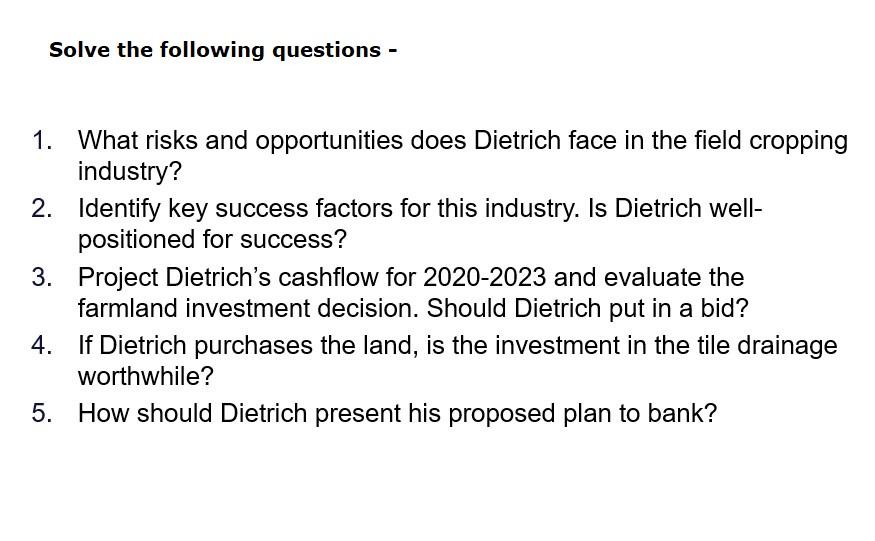

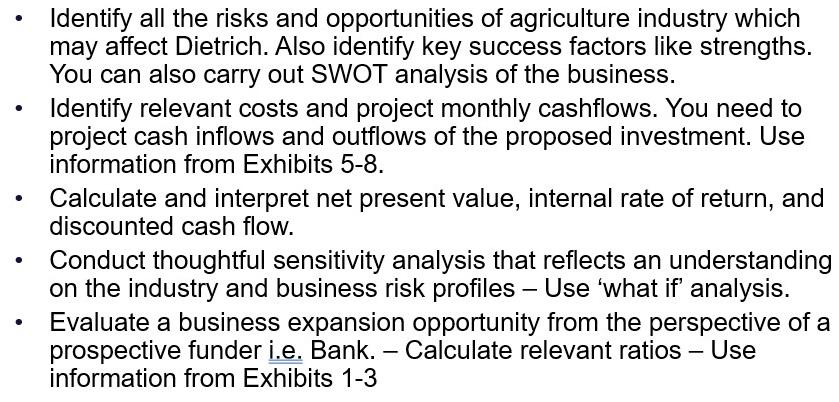

Paul Dietrich, a seventh-generation Canadian farmer, had successfully grown a sizable field crop business, Paul V. Dietrich Farms Ltd. (Dietrich Farms), in Southwestern Ontario. It was November 2020 and Dietrich was wrapping up his busy harvest season for the 1,100 acres 1 he currently operated. Although the fall harvest season demanded much of Dietrich's time and attention, he simply could not ignore an investment opportunity that had been presented to him. A local farmland owner was selling a 150-acre parcel of farmland that adjoined some land already owned by Dietrich (see Exhibit 1). The current owner wished to sell the property privately and offered the opportunity to bid to only two businesses: Dietrich Farms and another local dairy farm. Dietrich knew that the local dairy farm was eager to expand its land base and was aggressive with its plans to do so. Given that, and the recent appreciation in land values, Dietrich estimated that a competitive bid would need to be at least $20,000 per acre-more than his grandfather had paid for the entire parcel of land next door-and the bid would need to be made immediately. Dietrich sat down to evaluate the attractiveness of this opportunity and his ability to finance it. He knew that beyond the long-term financing required for the land purchase, he would also need to consider his short-term financing needs to navigate the seasonal nature of cash inflows and outflows that came with growing field crops. THE ONTARIO FIELD CROPPING INDUSTRY According to the 2016 Census of Agriculture, there were 49,600 farms in Ontario, with a total of 12,348,463 acres. 2 Of these farms, 16,876 farms, or 34 per cent, identified primarily as field cropping enterprises, producing grains and oilseeds. 3 The most grown field crops by acreage in Ontario were soybeans, corn, hay and fodder crops, and wheat. Field crops were used for many purposes including food for humans, food for livestock, and biodiesel and ethanol, as well as ingredients in everyday household products such as car parts, cosmetics, dyes, clothing, and more. 4 Fertile farmland was the foundation of field crop production. Each crop required a different set of nutrients from the soil, so farmers rotated their crops to maximize the use of nutrients in the soil and take advantage of the nutrients each crop would return to the soil. Crop rotation also benefited the soil in other ways: changing the type of roots benefited soil structure; rotating the crops added nutrients back to the soil, reducing the use of fertilizer; and rotating the crops minimized the opportunity for insects and diseases to target a crop year after year, reducing the need for pesticides. 5 Purchasing farmland was a major investment with land prices having increased significantly in value as commodity prices rose and land became an increasingly scarce resource (see Exhibit 2). It was estimated that 97 per cent of farms in Canada were family-owned and operated. Given that, it was not uncommon to see parcels of farmland owned by a family for decades, if not generations. 6 The equipment required to operate a field cropping business was also a significant capital investment. For example, a new combine (a vehicle used specifically to harvest field crops) with various harvesting heads cost approximately CA $850,0007 and a large tractor suitable for row cropping typically cost over $400,000.8 Over time, the agriculture industry had also become increasingly dependent on technology, and field cropping was no exception. Advanced seed genetics, global positioning systems (GPS), and automatic steering equipment were just a few examples of technological advancements that had the potential to benefit crop farms through improved efficiency, boosted profitability, or reduced environmental impact. From a financial perspective, the required land, equipment, and technology made the field cropping industry highly capital intensive (see Exhibit 2). At the same time, because most outputs were commodities, the industry had to deal with volatile prices (see Exhibit 3). A few tools helped mitigate the impact of this price volatility. Using futures markets, farmers could secure contracts to pre-sell their products at a predetermined price months or even years in advance of the growing season. Also, since prices were often lower at the time of harvest because of the plentiful supply, farmers could opt to store their crops in hopes of receiving higher prices later. Production and income from field cropping was volatile (see Exhibit 4). Field cropping was a seasonal business with most, but not all, crops being planted in the spring and harvested in the fall. Wheat could be planted in either spring or fall and harvested in either summer or fall, while hay could be harvested multiple times each year. 9 The success of a crop in any given year was also heavily dependent on weather conditions. Due to this unpredictability, farmers in Ontario could access production insurance, supported by the provincial and federal governments, to protect them from yield reductions and crop losses caused by factors beyond their control (i.e., adverse weather, disease, and wildlife and insect infestations). Production insurance guaranteed farmers a level of production based on their yield history and level of chosen coverage. Claims were paid out to a farmer if their yields fell below their guaranteed production. 10 DIETRICH FARMS Dietrich Farms was established in 2012 with Dietrich as the sole shareholder. He was the seventh generation of his family to farm in Canada and the third generation to farm specifically in the Lucan, Ontario, area. Dietrich's parents were also active farm owner-operators, and there was both formal and informal cooperation between the corporation owned by Dietrich and that owned by his parents. For example, the Dietrich family owned all its field equipment, and equipment owned by Dietrich Farms might be used by Dietrich's parents, or vice versa. Dietrich Farms had no employees, with most work done by Dietrich and his parents. Dietrich's brother worked a full-time job away from the farm, but he still helped with farm work consistently through the growing season. If the farm workload exceeded the family's capacity, Dietrich would hire nearby farm equipment operators to assist with the field work on a cost-per-acre basis. Dietrich's goal for growth was to acquire 100 acres of land every other year, ideally located within 15 kilometres of the farm's existing land for efficiency of transporting equipment. With all his investments, Dietrich aimed to achieve a 6 per cent rate of return. Dietrich's ties to farming were both professional and personal. While his business provided a financial return for him and his family (see Exhibits 5 and 6), he also took great pride in carrying on a family farming legacy and being part of an industry that fed Canadians and people around the world. FARMLAND INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY The 150-acre parcel that was available for sale was in Middlesex County, at the border between Middlesex and Perth Counties, an area known for highly productive soil. Dietrich felt bidding $20,500 per acre for this property was appropriate based on current market prices; he thought that would be considered a competitive bid by the seller. Dietrich used a three-year crop rotation on all his land, beginning with corn, followed by soybeans and then wheat. If he were to purchase the farm in November 2020, he would begin with corn in 2021 , followed by soybeans in 2022 and wheat in 2023 and then back to corn in 2024. This rotation would continue for the length of time that Dietrich owned the land. For 2021, Dietrich estimated that this new land would yield a corn crop of 220 bushels per acre, which he believed he could sell for $5.30 per bushel, with half of this revenue collected in November and the other half in December. However, experience had taught him that no two years of field cropping were the same and there could be unexpected outcomes. In Dietrich's farm career, the best corn crop he produced had a record high yield of 248 bushels per acre. Conversely, if his corn yields fell below 199 bushels per acre (his "guaranteed yield") in a poor growing season, this would trigger a payout from production insurance (see Exhibit 7 ). Dietrich had created detailed crop budgets that broke down the cost of growing each of the three crops on a per-acre basis and the timing of when those expenses were paid for (see Exhibit 8). Fertilizer and seed were purchased and paid for in the November before the growing season to take advantage of deep discounts provided by input suppliers. Most other costs were paid for during the growing season. Additionally, Dietrich estimated that this new farm would use up 10 to 15 per cent of his working time on an annualized basis. He typically withdrew a salary of $45,000 each year, and he didn't expect the amount of this withdrawal to change significantly. Dietrich had excess capacity with his existing fleet of equipment, so no additional investments in equipment would be required. However, he allocated the annual depreciation expense of his equipment fleet across all his farmland based on the crop grown on each property and the equipment time required for that crop. BOOSTING PRODUCTIVITY WITH TILE DRAINAGE Agricultural tile drainage was a system for removing excess moisture from soil below the surface. Excess subsurface water was counterproductive for agriculture for multiple reasons. First, roots of plants required air to live and grow, and excess water filled the pores of the soil, evacuating the air the roots needed. Second, excess water could limit the ability to access the land with heavy equipment, potentially delaying timesensitive activities such as planting in spring. 11 Dietrich estimated that it would cost $1,500 per acre to install a full systematic tile drainage system on the 150 -acre parcel. By reducing the risks associated with excess soil moisture, Dietrich estimated that he would achieve a 10 per cent boost to his yields, over and above his expected yield (see Exhibit 7 ). However, this improvement in production yield was a difficult number to estimate; in very wet weather years, the yield benefit from tiling could be closer to 20 per cent. Dietrich happily noted that a boost in yield likely resulted in no significant additional boost to costs. He was confident that the tile drainage would be effective for at least 25 years and perhaps as long as 50 , but he hoped it would pay for itself in 10 years. It had a capital cost allowance (CCA) rate of 25 per cent and no resale value at the end of its life. NEXT STEPS Dietrich set to work to analyze this opportunity from a variety of perspectives. He knew he wanted to begin by projecting his monthly operating cash flow from 2020 to 2023 to identify short-term financing needs, ignoring the tiling option. He knew he was heading into November with $500,000 in cash. His next step would be to consider the two independent, long-term investments-purchasing the 150 -acre parcel of land and investing in tile drainage - to see if they aligned with his target returns of 6 per cent. Dietrich understood that most financial institutions would provide financing for 75 per cent of farmland, and he felt comfortable assuming he would be able to access this level of financing given his experience with his banker. Dietrich expected his monthly loan payments to be $9,800 if he purchased the farm for $20,500 per acre. Given his age and stage of career, Dietrich opted to evaluate the investment in the additional 150 acres of land over a 10-year time horizon. He realized that ignoring any annual increase in crop prices over the life of the investment was a conservative approach, but he opted for that approach given the price volatility. As well, Dietrich knew that projecting the future value of this farmland at the end of 10 years would be challenging; however, based on the data he had (see Exhibit 2), he thought it was realistic to expect 10 per cent annual appreciation in farmland values for the foreseeable future. Still, Dietrich was concemed about the possibility of lower appreciation of farmland values. He was also cognizant of the tax implications of any appreciation in land values, in the form of capital gains taxes. At the time of selling any piece of land, Dietrich Farms would be required to pay capital gains taxes, which Dietrich understood was a tax at his regular corporate rate on 50 per cent of any realized gain. He assumed a tax rate of 15 per cent for all projections and analysis. Dietrich was also interested in understanding the financial impact of the drainage tile over the expected 25year minimum life and the required increase in yield. He decided to simplify his analysis and focus on an average increase in yield for his three crops; that is, he planned to calculate the expected increase in revenues, assuming the 10 per cent yield increase, for each of corn, wheat, and soybeans and then the average of those three. He would then use this average increased revenue for the 25-year period. Again, although conservative, he would assume zero price increases. Dietrich's goal was to understand whether a 10 per cent yield increase compensated for the cost of investing in tile. And if it did not, he wanted to know what the required yield increase would need to be. Last, if Dietrich were to pursue this land purchase, he needed to consider how best to approach his bank about this opportunity. He wondered what he might highlight from his cash flow and investment analysis as well as past financials or personal track record to give the bank confidence that this expansion would succeed and Dietrich would meet his financial obligations. He also wondered how the bank would view the rising debt levels in his farm. He worried that his debt-to-equity ratio would not be ideal; however, he knew that banks (and farm owners) typically looked at the market value of farmland when reviewing this ratio. Operating in an industry with high capital requirements, volatile prices, and production levels that varied at the whim of mother nature, Dietrich knew he needed a plan that was resilient to the various risks it could face. EXHIBIT 5: DIETRICH FARMS, INCOME STATEMENT, YEAR ENDED JUNE 30 EXHIBIT 6: DIETRICH FARMS, BALANCE SHEET, AS AT JUNE 30 2018Actual2019Actual2020Actual Assets Current Assets Cash Accounts receivable Income tax receivable Inventory Prepaid expenses Capital assets Total Assets Liabilities Current Liabilities Shareholder's Equity Share capital Retained earnings Total Shareholder's Equity Total Liabilities and Shareholder's Equity EXHIBIT 7: CROP PRODUCTION PLAN WITH YIELD AND PRICE EXPECTATIONS e: Company files. EXHIBIT 8: PRODUCTION COSTS BY CROP, PER ACRE In November 2020, Paul Dietrich, a seventh-generation Canadian farmer, was presented with an investment opportunity. A local farmland owner was selling a 150 acre parcel that adjoined some land Dietrich already owned. The current owner wished to sell the property privately and offered the opportunity to bid to only two businesses: Paul V. Dietrich Farms Ltd. (Dietrich Farms) and a local dairy farm. Dietrich knew that the local dairy farm was eager to expand its land base and was aggressive with tits plans to do so. Given that and the recent appreciation in land values, Dietrich estimated that a competitive bid would need to be offered to get the deal. Dietrich wanted to evaluate the attractiveness of this opportunity, considering the long-term financing required for a land purchase as well as short-term financing needs to navigate the seasonal nature of cashflows that came with growing field crops. He new it would be imperative to consider both how this opportunity would be perceived by his bank and how best to present this opportunity to his bank. He also wanted to evaluate whether an investment in tile drainage would be worthwhile should he be successful in purchasing the 150-acre parcel. Concepts in Practice 1. Classification of risks: - Business Risk Vs. Financial Risk - Market Risk, Credit Risk, Operational Risk - Leverage and Break Even Analysis 2. Cost of Capital : Financing cost 3. Capital Budgeting: - Discounted Cash flow methods of evaluation : NPV and IRR 4. Risk Analysis in Capital Budgeting - Sensitivity Analysis and Scenario Analysis Solve the following questions - 1. What risks and opportunities does Dietrich face in the field cropping industry? 2. Identify key success factors for this industry. Is Dietrich wellpositioned for success? 3. Project Dietrich's cashflow for 20202023 and evaluate the farmland investment decision. Should Dietrich put in a bid? 4. If Dietrich purchases the land, is the investment in the tile drainage worthwhile? 5. How should Dietrich present his proposed plan to bank? - Identify all the risks and opportunities of agriculture industry which may affect Dietrich. Also identify key success factors like strengths. You can also carry out SWOT analysis of the business. - Identify relevant costs and project monthly cashflows. You need to project cash inflows and outflows of the proposed investment. Use information from Exhibits 5-8. - Calculate and interpret net present value, internal rate of return, and discounted cash flow. - Conduct thoughtful sensitivity analysis that reflects an understanding on the industry and business risk profiles - Use 'what if' analysis. - Evaluate a business expansion opportunity from the perspective of a prospective funder i.e. Bank. - Calculate relevant ratios - Use information from Exhibits 1-3