Question: Please help with coming up with an introduction for this case. Can be put into bullet points on items to discuss. Thank you! Use the

Please help with coming up with an introduction for this case. Can be put into bullet points on items to discuss. Thank you!

Use the introduction to identify the company to be analyzed. In addition, tell us enough about the key facts in the case so that we can follow your analysis. These facts would be the ones that have affected the companys strategic direction and performance. Include a brief statement that lists the conceptual models that will be employed in your analysis.

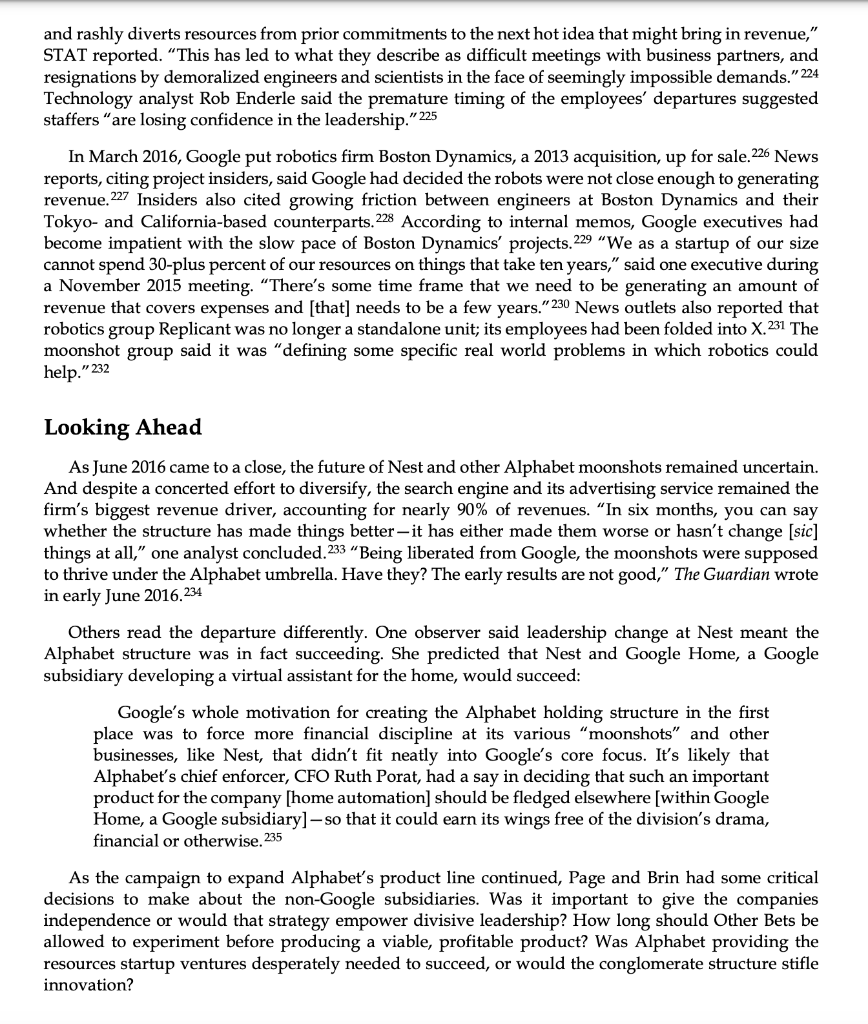

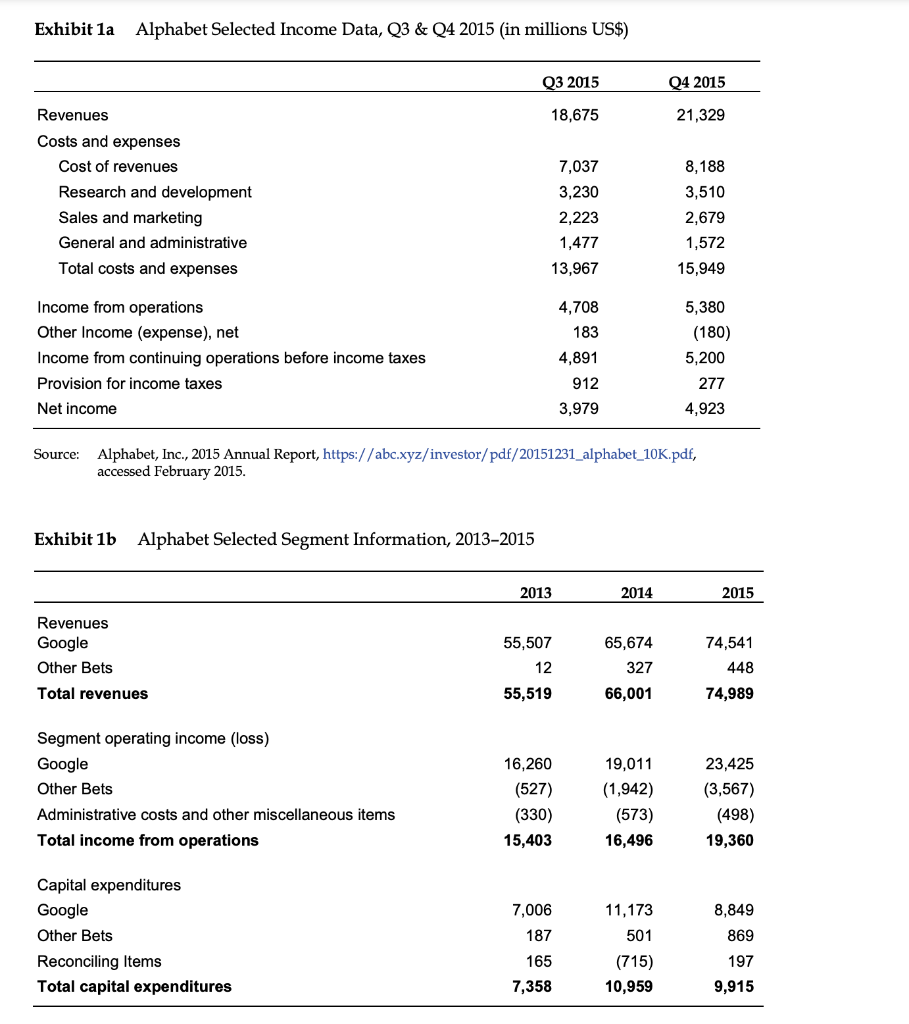

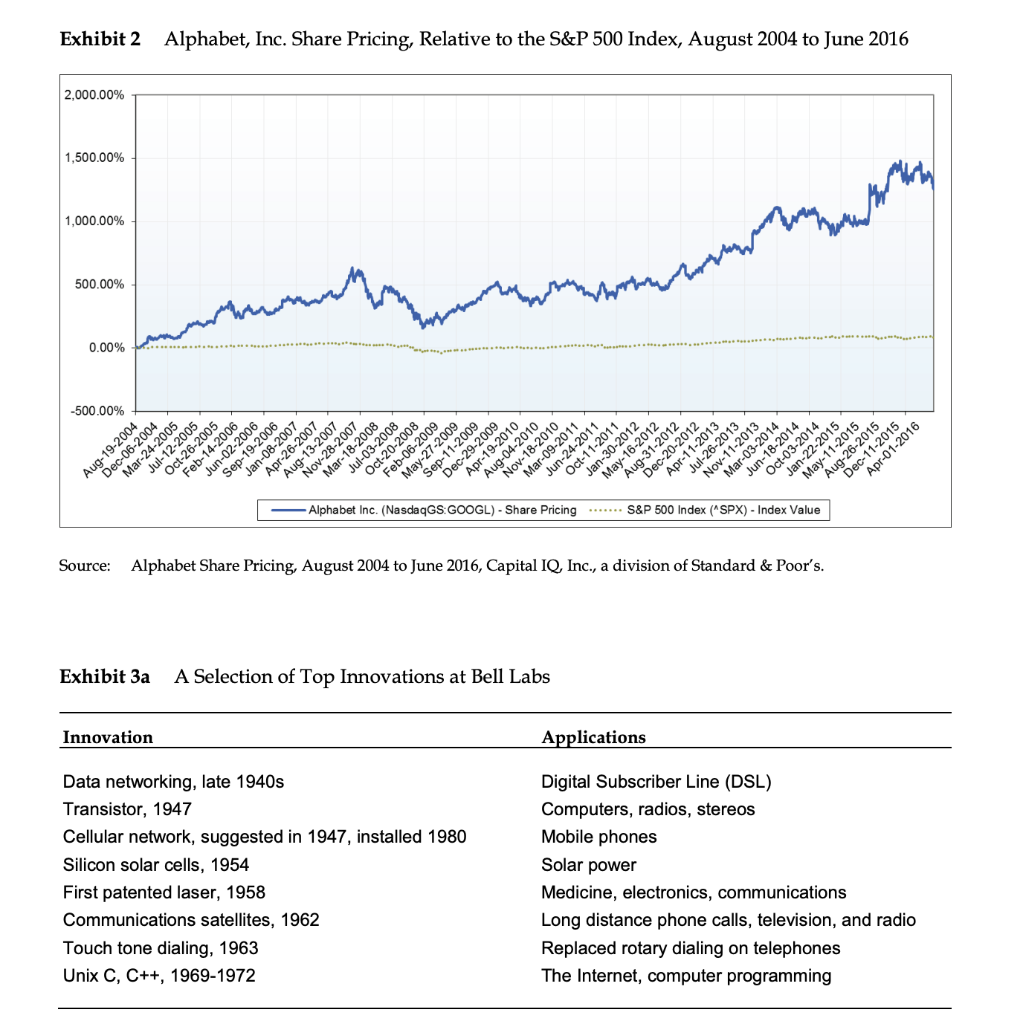

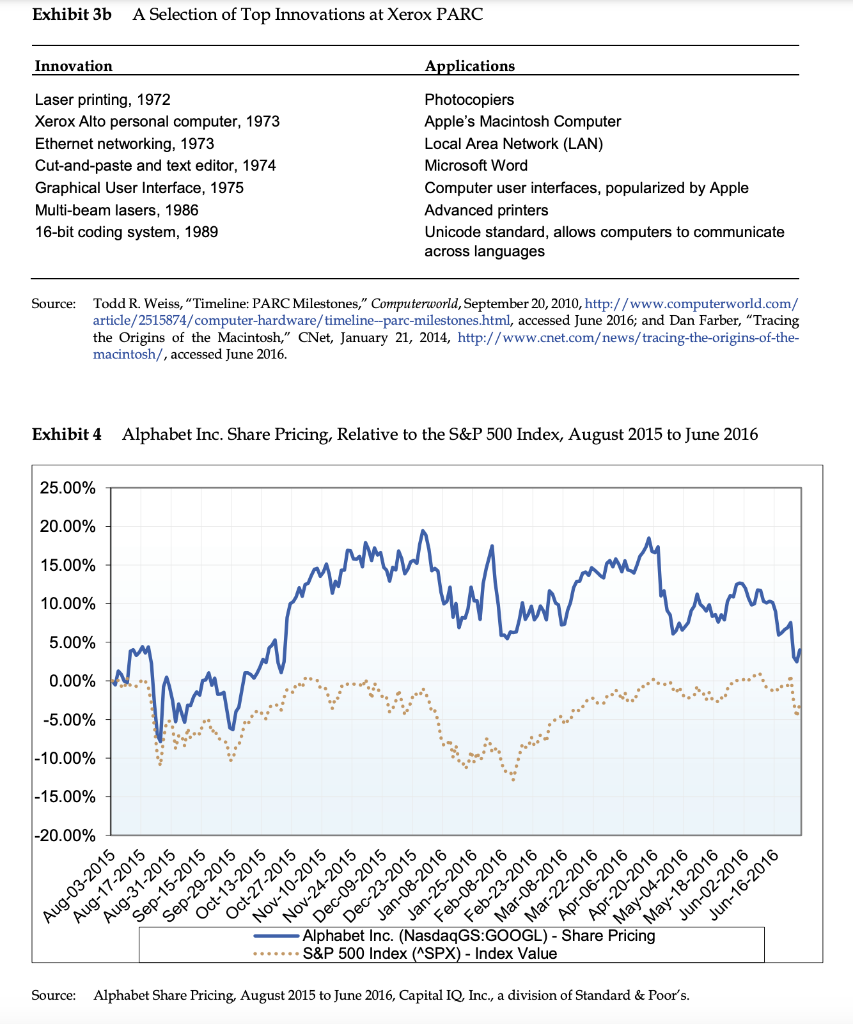

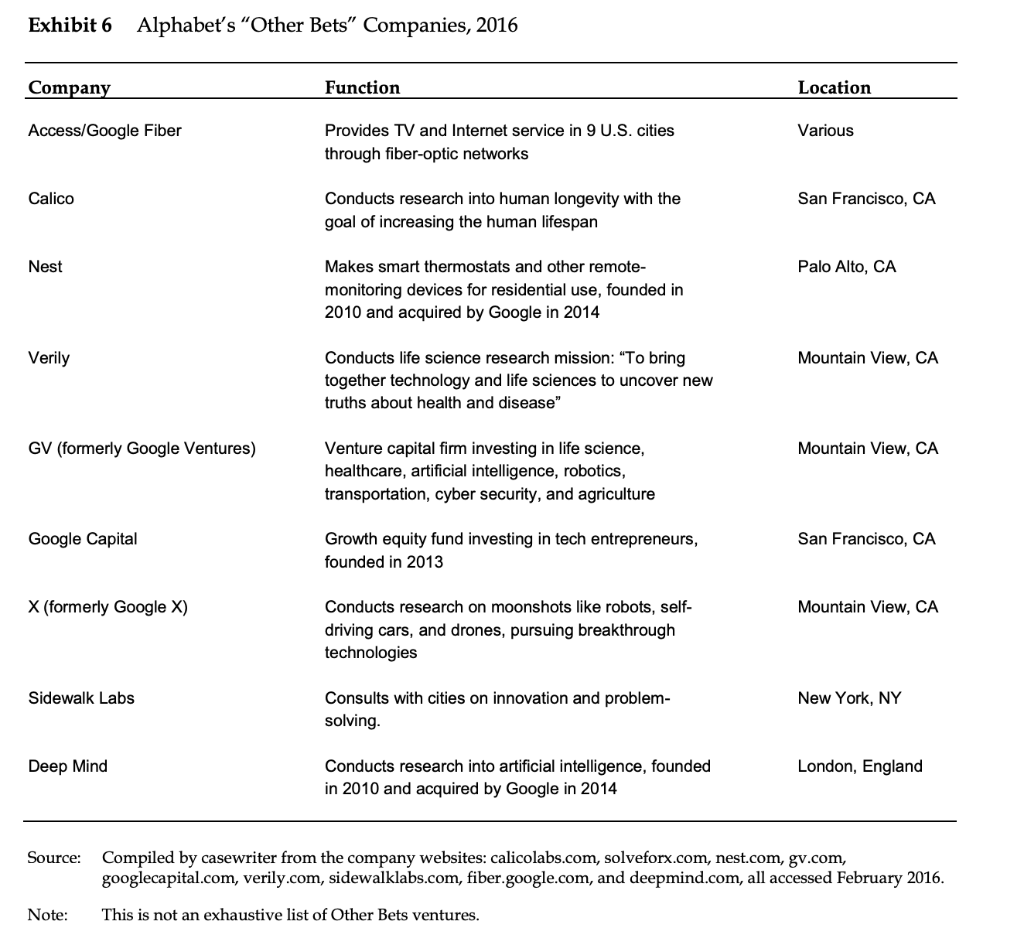

Alphabet Eyes New Frontiers We'd like to have a bigger impact on the world by doing more things. - Larry Page, Cofounder and CEO of Alphabet 1 In June 2016, Tony Fadell announced that he was "leaving the nest" after six years at the helm of Nest Labs, an Alphabet subsidiary that made smart household appliances. "I'm a guy who's at the beginning of things," he told the New York Times. "I don't like to do maintenance mode. It's not what gets me out of bed." 2 The news followed press reports that revealed turmoil at Nest and raised questions about Google's recent decision to restructure into Alphabet, a holding company. When the reorganization had first been announced in August 2015, experts said Nest would be among the main beneficiaries. "Nest and the rest gain more freedom to spend money, acquire other companies, etc. without having to try to explain how such costs are benefiting the core ad business when they clearly were not," one analyst noted. 3 "[Alphabet's] new stand-alone companies will have more freedom to take risks," another observer commented. 4 But when internal problems at Nest and other subsidiaries surfaced in the press, observers began to fault the reorganization. "Google cofounders, now Alphabet honchos, really want to replicate their search engine's success across a range of industries with operations run like startups," one observer wrote. "To do that, though, they have to face a dilemma inherent in their structure. That is, they must find execs willing to work within Alphabet's corporate umbrella, and teams willing to work with their chosen execs." 5 The makeup and management of Alphabet's diverse collection of subsidiaries had been in flux since the restructuring announcement. In August 2015, a day after Google announced that it would reorganize, gaming subsidiary Niantic, an early "autonomous business unit" under Google, 6 said it would become an independent company. 7 In December 2015, life sciences subsidiary Verily announced the creation of a new surgical solutions venture that would also spin off. 8 Also that month, Bloomberg reported that Alphabet would soon create a separate subsidiary to house the company's self-driving car project, which had been the founding project of Google's X lab. 9 News outlets reported on a growing culture of fiscal discipline at Alphabet, where subsidiaries were now being asked to pay the parent company for shared services. 10 And in March 2016, Alphabet's robotics subsidiary, Boston Dynamics, was reportedly put up for sale. 11 Against this backdrop of change, long-time Google observers wondered, were Nest's problems evidence that the new corporate form was incompatible with the ambitious innovation agenda set out by Google's founders, or would it in fact make it easier to deliver breakthrough innovations to market? And did it make sense to host such a large and diverse set of "moonshots" under a single corporate owner? Google's Rise Founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin met at Stanford University in 1995. At first, they called their search engine "BackRub," but in 1997, they registered the domain Google.com. The name referred to the number googol, which is equivalent to 110100. In 1998 , Google, Inc. filed for incorporation in California, with headquarters based in a garage in Menlo Park, California. By 2000, Google had become the largest search engine in the world, with an index of 1 billion pages, 12 and in 2006, "google" became a verb in the Oxford English Dictionary. 13 In 2015, Google had 64% of the U.S. market share of search; no other competitor had even 20%14 That year, revenues came in just under $75 billion, with total assets of $147 billion by December 2015. 15 (Exhibits 1a and 1b provide information on Alphabet's financials.) Eric Schmidt came to Google as chairman in March 2001 and became CEO a few months later. He shared management responsibilities with the two founders. Schmidt had risen to prominence during his successful tenure at Sun Microsystems and had been running Novell since 1997. Brin and Page were impressed by Schmidt and felt he would be the right fit to round out the professionalism and management expertise of their youthful leadership team. Schmidt oversaw the company's IPO in 2004 and, in his first few years at the company, saw Google through its expansion into several new products and services, including Google News, Blogger, Google Books, Gmail, Google Earth, Google Maps, and the acquisitions of YouTube and DoubleClick. Investor Relations In August 2004, Google became a publicly traded company in a controversial initial public offering (IPO) that lagged many investors' expectations. 16 Both the initial share price of $85 and demand for the stock were lower than Google expected. 17 The IPO was unusual for two reasons. First, the founders opted to run the IPO in a rare auction format, which precluded the underwriters from setting an opening price, marketing the IPO on behalf of Google, and earning high fees on the transaction. 18In marketing its own IPO, Google faced criticism for failing to answer investors' questions, such as how the company planned to spend the money it raised. 19 Some felt that Google had alienated investors and investment banks by eschewing the standard Wall Street IPO process. 20 "Their mantra was "Trust us,'" said one hedge fund manager. "That doesn't work for a company with a high price if you have no idea what the future will bring." 21 Also unconventional was Google's election of a dual stock structure, in which Class A shares carried one vote each while Class B shares, reserved for Google insiders, carried 10 votes. 22 In a letter to prospective investors, Page and Brin explained that choice: [The] standard structure of public ownership may jeopardize the independence and focused objectivity that have been most important in Google's past success and that we consider most fundamental for its future. Therefore, we have implemented a corporate structure that is designed to protect Google's ability to innovate and retain its most distinctive characteristics. We are confident that, in the long run, this will benefit Google and its shareholders, old and new. 23 On the first day of trading following the auction, Google stock climbed above $100 per share. 24 The stock jumped 1,294% over the next 10 years, outperforming all but 10 other stocks during the same period. 25 (See Exhibit 2 for Alphabet share pricing since the IPO.) By many accounts, Google's relationship with investors had two sore spots: its approach to corporate governance and its large, opaque research budget. Shortly after Google's IPO, the Institutional Shareholder Services, which advised institutional investors, gave the company a lower corporate governance rating than all the Fortune 500 firms. 26 Corporate governance experts said the dual class structure was "problematic" and amounted to "benevolent despotism." 27 In the 2004 prospectus, Google itself admitted that the structure "will make it harder for outside parties to take over or influence Google." 28 The structure made it difficult if not impossible for activist investors to gain traction. 29 "The attitude Google has toward outside investors is worth watching," one analyst said. "But in the end, you are basically buying management. You either think they are capable or you don't. If Sergey and Page don't make it here, there won't be anything left." 30 In early 2011, Schmidt brought Page back as CEO of Google after a 10-year hiatus, announcing via Twitter, "Day-to-day adult supervision no longer needed!" 31 Schmidt became executive chairman, announcing he would focus "externally on deals, partnerships, customers and broader business relationships." 32 That April, Page moved to increase capital expenditures and significantly expand Google's workforce. 33 Some predicted that these investments would make shareholders impatient. "Having a Google that's a little more willing to invest in what they have, in order to build out beyond search, will ultimately create shareholder value," 34 one analyst commented. "But that's not going to make the next few quarters look how they'd like." 35 In March 2014, Google introduced a new share class, Class C, which carried no voting power. 36 Shareholders tried to prevent the change with a resolution that would have ensured equal voting rights, but a resolution introduced by Brin and Page defeated it. 37 Some thought the shift would create future problems for shareholders. "What comes out of Google ten years from now is probably dysfunctional," one technology investor said. 38 Unlike other technology companies, Google did not pay dividends to shareholders. 39 Innovation at Google Google embraced unconventional human resources practices in the interest of fueling innovation. One of its most famous employee perks was known as " 20% time." In their 2004 letter, the founders explained, "We encourage our employees, in addition to their regular projects, to spend 20% of their time working on what they think will most benefit Google." 40 Several successful Google products had been invented during 20% time, including Google's autocomplete system, AdSense, 41 the advertising technology behind Gmail (Ad Sense); Google News; Gmail; and even the buses that transported Googlers to work..42 Ad Sense alone brought in about one-fourth of Google's annual revenues. 43 There was no shortage of ideas at Google; projects born during 20% time numbered in the thousands. 44 In 2011, Page began an annual campaign to offload the projects that had failed to catch on or had been made redundant by other products on the market. 45 "There were so many interesting projects going on that almost nothing had enough investment to be truly great," said CEO of People Operations Laszlo Bock. 46 In addition to 20% time, Googlers were offered five-month maternity leave, on-site laundry, free meals, and even death benefits. 47 "At times Google's largesse can sound excessive-noble but wasteful from a bottom-line perspective," an observer noted. 48 Work spaces at the "Googleplex" in Mountain View were designed to promote what Bock termed "casual collisions" between coworkers. 49 The inspiration for this choice came from Bell Labs, the historic research arm of AT\&T. Bock explained: When they built the buildings that Bell Labs were in, they set up the buildings where there's a long corridor down this long building, and all the offices were off to the sides. And the thesis was people would kind of stumble out of their offices and bump into each other and have interesting conversations. There's a direct line from that to the way, for example, at Google we run our cafes, where we have these round tables and long tables where you end up sitting next to strangers and bumping into them. And we try to manufacture these moments of serendipity in much the way Bell Labs did. 50 To encourage risk-taking, Google leadership embraced failure. One of the company's public failures was Google Wave, a live messaging platform that allowed users to collaborate on documents in real time. Less than six months after introducing the service in March 2010, Google pulled the project due to low user adoption. 51 Bock explained, "The team ... took a massive, calculated risk. And failed. So we rewarded them," with bonuses. 52 He added, "The biggest lesson was that rewarding smart failure was vital to support a culture of risk-taking." 53 Page gave one project manager some advice when he was hired: "It's O.K. if you fail, I just want you to fail quickly." 54 In March 2015, the Wall Street Journal reported that Google was investing more resources in Advanced Technology and Projects (ATAP), the research lab that limited projects to two years, while scaling back support for other innovative projects. 55 "One week of their time is one percent of their entire duration in ATAP," said ATAP's founder. "That makes them impatient with bureaucracy and process. And with a small enough group, you can start to strip away those things and go really fast." 16 Investors were pleased. "If Google can make research projects shorter and with less investment, that's positive," one analyst said. "It's going to be less worrying if projects fail." 57 Loving the Googleplex Each year more than 2 million people applied to work for Google. 58A 2015 survey found that Google was the preferred employer of both engineering students and business students. 59 "Millennials want to truly understand a company's purpose, align with it, and work with others to propel the organization's performance," the study's authors commented. "Millennials are highly attracted to entrepreneurial energy in the workplace." 60 About 89% of Googlers gave their employer a high satisfaction rating in 2015, according to PayScale. 61 "Google works from the bottom up," explained one Google engineer. "If you have a great technical idea, you don't have your V.P. send out a memo telling everybody to use it. Instead, you take it to your fellow engineers and convince them that it's good." 62 Google leadership sought to establish a culture where employees felt comfortable speaking up. 63 "People with vision were given the opportunity to create their own Google," Bock wrote in his 2015 book, Work Rules! 64 Leaving the Googleplex Despite an effort to create what one spokesman called "the happiest, most productive workplace in the world," 65 large numbers of Googlers left after short tenures. Between July 2012 and July 2013, Google was ranked fourth in a list of Fortune 500 firms with highest employee turnover. 66 Though employees enjoyed a median pay of $107,000, they only stuck around for a median of 1.1 years 67 Part of this, experts explained, was a function of Google's exponential growth; between 2007 and 2013, Google added 19,000 employees. 68 One engineer who left the company in 2012 said the former "innovation factory" had become preoccupied with beating rival Facebook in advertising. 69 "The Google I was passionate about was a technology company that empowered its employees to innovate," he wrote. "The Google I left was an advertising company with a single, corporate-mandated focus."70 Another cited "creeping bureaucracy" as the reason she left Google. 71A third said she wanted to run her own show: "Google is a great training ground for how to build an amazing culture and an amazing product. But Google is not that good at teaching you how to build a business."72 An eight-year Google veteran felt too sheltered from failure at Google: "Google teaches you so much, but it also buffers and protects you."73 Some executives left to start their own firms, many of which Google funded through its venture capital department, Google Ventures (GV). 74 One ex-Googler who went on to start a company commented, "Google has always wanted to have a major impact on the world. Having us go to other companies is an extension of that." 75 Investing Outside the Core From the beginning, Google's founders vowed to take the long-term view. "Despite the quickly changing business and technology landscape, we try to look at three to five year scenarios in order to decide what to do now," the founders wrote in 2004.76 They warned investors that the company would "place major bets on promising new opportunities," incurring substantial risk. 77 "We will not shy away from high-risk, high-reward projects because of short term earnings pressure," they wrote. 78 And, although online advertising accounted for the vast majority of Google's total revenues ( 95% in 2012), the company also showed a strong interest for the pursuit of new opportunities beyond search. Page appeared to believe that Google had a significant margin for expansion. "You know, we always have these debates: We have all this money, we have all these people, why aren't we doing more stuff?" he said in 2013. 79 "You may say that Apple only does a very, very small number of things, and that's working pretty well for them. But I find that unsatisfying. I feel like there are all these opportunities in the world to use technology to make people's lives better." 80 He pointed to a tension between investors and taking risks: "Investors always worry, ' Oh, you guys are going to spend too much money on these crazy things.' But those are now the things they are most excited about ...."81 Some argued that Google had no choice but to diversify to ensure future growth. "If you think historically, go back 30 or 35 years, the organizations with big R\&D [Research and Development] divisions were AT\&T, IBM, and Xerox," said one academic. 82 "Notice that each of those companies had a de facto monopoly." 83 But others noted that these very companies had poured large sums of money into R\&D, but often failed to profit directly from new discoveries. 84 (Exhibits 3a and 3b show innovations at Bell Labs and PARC.) Early Investments In a 2005 discrete transaction, Google acquired Android, a small software company, at an estimated price of up to $50 million. 85 "The bet that Larry, Sergey, and Eric made at the time was that smartphones are going to be a thing, there's going to be Internet on it, so let's make sure there's a great smartphone platform out there that people can use to, among other things, access Google services," said Hiroshi Lockheimer, Google's Vice President for Engineering at Android. 86 By 2015, Android had become the most popular mobile operating system in the world. 87 Increasingly, however, cell phone makers were altering the operating system to disengage Google's apps. "About 30 percent of Android smartphones shipped in the last quarter of 2014 were actually modified, or forked, versions of the OS that may not be very hospitable to Google's services, according to the firm ABI Research," the New York Times reported. 8 In October 2006, Google agreed to buy the popular online video site YouTube for $1.65 billion in stock. (Eric) Schmidt called it "the beginning of an Internet video revolution." 89 At the time, there was significant doubt as to whether user-generated content sites would attract top advertisers. YouTube was considered an unproven entity, and many were perplexed by the high price Google paid for a company with a string of losses and no clear path to profitability. 90 In 2016, this acquisition was generally viewed as successful, with YouTube's annual ad revenues estimated at several times the 2006 purchase price and growing. However, the unit's overall contribution to Alphabet remained unclear. Less than a year later, in A pril 2007, Google announced that it would acquire the online advertising company DoubleClick for $3.1 billion in cash. This purchase price, over 20 times revenue, was even more perplexing.91 Wall Street analysts viewed it as a sign that Google was willing to spend anything to keep Microsoft off its online advertising turf. 92 Schmidt said the purchase would improve the enduser experience, but the press and shareholders felt his explanation was light and his rationale was vague. Moonshots In 2010, Google X became the home of Google's riskiest projects, called "moonshots." 93 The secretive lab pursued futuristic ideas like driverless cars, Wi-Fi balloons, and smart eyeglasses. 94 Google X projects were chosen if they had potential to affect millions of lives and employed existing technologies. 95 Research activities at Google X were closed off from the rest of Google; other Google employees were denied entry to the building. 96 The 1X " was originally just a stand-in for a better name, 97 but some Googlers said it indicated that X was willing to invest in projects that were 10 years away from large-scale implementation. 98 Within Google X, projects could fail as long as the group was commercially viable. 99 "The portfolio has to make money," said Obi Felten, whose title at Google was "Head of Getting Moonshots Ready for Contact with the Real World." She added, "Some of these will be better businesses than others, if you want to measure in terms of dollars. Others might make a huge impact on the world, but it's not a massive market." 100 In February 2016, Astro Teller, the head of X, gave a speech titled "The Unexpected Benefit of Celebrating Failure," in which he described several X projects that had been discontinued in recent years, including a project to automate vertical farming that failed to grow staple crops and a lightweight cargo ship that would have cost $200 million to prototype. 101"WeworkhardatX to make it safe to fail," Teller said. "Teams kill their ideas as soon as the evidence is on the table because they're rewarded for it. They get applause from their peers. Hugs and high fives from their manager, me in particular. They get promoted for it. We have bonused every single person on teams that ended their projects, from teams as small as two to teams of more than 30. "102 Also in 2010, Page began secretly funding a startup based near Google's Mountain View, California, campus that was working to invent the flying car. 103 "Page is using his personal fortune to build the future of his childhood dreams," Bloomberg reported. 104 Some said Google's ambitious research activities made it easy to recruit talent. "These fantastical ideas create a growing halo around the company, fostering the perception that Alphabet [Google] is a place where magic happens, where the most innovative minds from iPod creator Tony Fadell to life sciences' chief Andy Conrad, come to tinker," a Fast Company contributor wrote. 105 For every 100 ideas that fail at Google's X division, "an army of new fans gets minted." 106 But investors continued to voice concerns about the reporting of internal investments. 107 "There are some investors who have been looking at Google and saying, 'They spend like crazy and I have zero recourse to change the direction, so I don't want to be involved with them, '" said one analyst. 108 In September 2013, Page introduced Calico, a lab probing human longevity. He assured investors that the project was in line with the company's mission, stating: You're probably thinking wow! That's a lot different from what Google does today. And you're right. But as we explained in our first letter to shareholders, there's tremendous potential for technology more generally to improve people's lives. So don't be surprised if we invest in projects that seem strange or speculative compared with our existing Internet businesses. And please remember that new investments like this are very small by comparison to our core business. 109 In June 2014, analysts called for greater transparency in Google's expense line, noting that while revenues went up 22-fold between 2004 and 2014, expenses increased 23-fold. 110 Pointing to a decline in capital expenditure efficiency, the analysts contrasted investments like Android, DoubleClick (the advertising subsidiary), and YouTube with the company's new investments like the self-driving car and the smart home, projects with less "transparent monetization potential." 111 Google's then-CFO emphasized a conservative approach to research spending. "I just want to kind of reaffirm to you that we do it in a smart way and a disciplined manner," he said in a call with investors. "We're driving forward to make sure we don't waste our shareholders' money." 112 The thenhead of Google X defended his division. He compared expectations for X to those of a venture capitalist who invests in a young company. "Because risk abounds, we owe a very strong return," he said. 113 In 2014, Google spent 12% of its revenues on research and development, the highest percentage since the company's 2004 IPO. 114 In all, the company spent $9.8 billion on R\&D, up 38\% from 2013. 115 Meanwhile, online advertising continued to dominate, generating nearly 90% of total revenues in 2015. 116 Some of those profits had been funding the company's moonshots, but consolidated reporting made it difficult for investors to evaluate the performance of these riskier endeavors. Other Moonshot Factories Though perhaps less extravagant than Google's big bets, other technology companies had their own moonshot factories. In addition to its core business, an online retail store, Amazon contained several other ventures, including drone, data storage, video streaming, publishing, and tablet units under its umbrella. 117 "Most large organizations embrace the idea of invention, but are not willing to suffer the string of failed experiments necessary to get there," noted CEO Jeff Bezos. 118 Similarly, Facebook operated WhatsApp, virtual reality company Oculus Rift, Instagram, drone company Ascenta, and an artificial intelligence initiative, in addition to its core social media platform and ad tech businesses, all of which furthered Facebook's business goals. 119 "We like problems that have very low business risk and very high technical risk," said CTO Mike Schroepfer. "Meaning, we know what we will use this for, but we have no idea whether you can actually get it done." 120 Apple, the largest public corporation in the world by market value, spent less on R\&D than other top technology firms as a portion of revenue. In fiscal year 2015, Apple spent only 3.5% of its revenue on R\&D, compared with Facebook's 21% and Alphabet's 15\%. 121 In 1998, Apple founder Steve Jobs said, "Innovation has nothing to do with how many R\&D dollars you have."122 Still, Apple was reportedly pursuing some ambitious projects, including a self-driving car and a pay TV project. 123 Trends in Technology In 2015, McKinsey consultants counted 146 private tech companies worth $1 billion or more (known as "unicorns"), 14 of which were valued above $10 billion. 124 (See Exhibit 8a for a graph showing U.S.listed tech IPOs, 1995-2015, and Exhibit 8b for all U.S. IPOs since 1980.) Meanwhile, an estimated 40\% of such firms saw their valuations drop between 2011 and 2015.125 "There is demand, too-just not at the valuations VCs have given the startups," said one analyst. 126 Said another, "Many of the jazzier companies found they could raise virtually infinite amounts of money while staying private. Had Google and Facebook had the option, they probably would have stayed private longer."127 Ruth Porat In March 2015, Google hired Wall Street banker Ruth Porat to serve as CFO. "We're tremendously fortunate to have found such a creative, experienced and operationally strong executive," Page said. "I look forward to learning from Ruth as we continue to innovate in our core from search and ads, to Android, Chrome and YouTube as well as invest in a thoughtful, disciplined way in our next generation of big bets." 128 Porat came to Google from financial-services firm Morgan Stanley, where she was CFO and had advised technology clients like Amazon and eBay. 129 Analysts interpreted the hire as a shift in priorities toward expense reduction. "The perception has long been that they throw money at things," one analyst said. "That's not going to change because of one earnings report, but with her there and showing a serious commitment to some discipline, it becomes part of a story line. People are saying there's probably a lot more that could be cut. If so, Google could be a very strongperforming stock." 130 On her first call with investors as Google CFO, she presented the second-quarter earnings report, indicating she would in fact move to keep expenses in check. "A key focus is on the levers within our control to manage the pace of expenses while still ensuring and supporting our growth," Porat said. 131 Investors responded enthusiastically to the earnings report, which exceeded their expectations, 132 and Porat's commitment to fiscal discipline; the next day Google stock climbed 16.3%, boosting the company's market value by nearly $65 billion. 133 "She gave a lot more qualitative and directional information than her predecessors and she seems to be more in-tune with the investor community," one analyst noted. 134 Google Announces Restructuring On August 10, 2015, Google announced that it would restructure and create a new holding company named Alphabet. Page, the CEO of Google since 2011, announced that he would become the CEO of Alphabet, 135 and would promote Sundar Pichai, former Senior Vice President of Google-branded products, 136 to CEO of Google. 137 Page and Brin would run Alphabet, along with Porat. Schmidt would remain executive chairman. The Google subsidiary included its Internet-related businesses, such as search, advertising, maps, YouTube, and Android phones. The non-Google subsidiaries included DeepMind, an artificial intelligence company; 138 Nest, a smart home thermostat system; Fiber, an Internet service; Calico, a longevity research lab; X, the moonshot incubator; Sidewalk, an urban technology project; and two investment arms, GV and Google Capital. 139 (Exhibits 5 and 6 provide a selection of Google and non-Google subsidiaries, with brief descriptions of each.) Under the restructuring, existing shares of Google would convert to Alphabet shares and trade under the same stock tickers as before, GOOG and GOOGL. 140 The change had implications for the way Google reported earnings to investors; Google planned to introduce segment reporting so that Google earnings could be viewed separately from the other business segments at Alphabet. 141 In August 2015, Page and Brin held more than 50% of the voting stock in the company.. 142 Larry "Warren Buffett" Page? "In general, our model is to have a strong CEO who runs each business, with Sergey and me in service to them as needed," Page wrote in a public post on the Alphabet website (abc.xyz). 143 Reorganization would allow the company more management scale, Page wrote, adding, "We can run things independently that aren't very related." 144 Google's founders had long drawn inspiration from businessman Warren Buffett, the CEO of Nebraska-based holding company Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Page and Brin cited Buffett's writing as a major influence for their Google's 2004 Founders' IPO Letter, 145 and often praised him publicly. 146In creating Alphabet, Page said Google leadership borrowed "aspects" 147 of the Berkshire Hathaway model. "I think there's things that they do really well," he said. 148 In 2015, Berkshire Hathaway was the 14th largest company in the world by revenue. 149 Since Buffett bought failing textile company Berkshire Hathaway in 1965 , the stock price had increased 1,826,163\%, growing 21.6% on average each year. 150 Google's move to restructure inspired further comparison between the two companies. Like Alphabet, Berkshire Hathaway had a diverse array of subsidiaries, including Geico insurance, See's Candies, Helzberg Diamonds, and Heinz Ketchup, which were all run independently. 151 "Google's Alphabet sounds like a 21st century Berkshire Hathaway," LinkedIn CEO Jeff Weiner wrote on Twitter when Google's plans to restructure were announced. 152 Though Buffett controlled a large portion of Berkshire Hathaway shares, his companies operated more or less independently. 153 "We will continue to operate with extreme - indeed, almost unheard of - decentralization at Berkshire," Buffett wrote in his 2016 letter to shareholders. 154 Like Alphabet, Buffett's holding company had a dual share class structure, with B shares trading at lower prices. 155 In 2014, when Buffett held a 20% stake in his company, shareholders rejected a dividend proposal. 156 "Now, you may think that I stuffed the ballot box," Buffett said at the time. "I did." 157 Porat said the Google founders shared Buffett's commitment to "long-term value creation" 158 and "backing great leaders." 159 Some observers were less convinced. They pointed out that unlike Alphabet's founders, Buffett had not historically invested in technology. 160 In addition, Berkshire Hathaway's subsidiaries were generally added to the portfolio via acquisition, while Alphabet's ventures were commonly developed internally. 161 Investors Relations Investors cheered the new structure. When the news broke on August 10, Google's shares-which lagged during the first two quarters of 2015 - climbed 6.2% in late trading. 162 Analysts viewed the new corporate structure as evidence that Google's attitude toward investors had improved. "We continue to think an era of more disclosure and cost consciousness ... is positive for Google," said one analyst. 163 Another analyst called it a "positive surprise" 164 from Porat, a "Wall Street veteran known for complex financial engineering." 165 On October 2, 2015, Alphabet, Inc. became officially incorporated in the state of Delaware. 166 That day, Alphabet shares surged 2.3\% to $657 apiece. 167 (Exhibit 4 shows the Google (Alphabet) stock price between August 2015 and June 2016.) During the fourth quarter of 2015, Alphabet had a higher percentage of institutional fund ownership (31\%) than any other stock. 168 "Alphabet has a best-possible 99 IBD Composite Rating, meaning it's outperformed 99% of all stocks on key metrics such as sales and profit growth in recent quarters," one observer commented. 169 In October 2015, Porat announced Alphabet's first-ever share buyback (a $5.1 billion purchase). 170 By February 2016, Alphabet stock was nearly 50\% above share prices in summer of 2015.171 (See Exhibit 7 for a chart showing the major institutional investors in March 2016.) Innovation Following the restructuring announcement, Alphabet leadership also reiterated a commitment to nurturing long-term projects. In November 2015, Page indicated that the incubation period for a moonshot was generally longer than a venture capitalist's investment. "I think a lot of the things we are doing we have a lot of conviction about them working over time, but I think a lot of them have the characteristic of taking longer than an average venture capital bet," Page said. 172 In October 2015, Porat described Alphabet's approach of monitoring spending while optimizing value: "[The restructuring] wasn't about cost cutting our way to greatness, it was about ensuring that we have the same very detailed, disciplined approach to looking at the growth and expenses, making choices in order to optimize while still supporting revenue growth."173 Porat went on to outline Alphabet's "70:20:10 system" in which 70% of the company's resources were spent on the core, 20% on adjacent projects, and 10% on research. 174 For some, the creation of Alphabet marked a cultural shift. "It is such a large company now and with all large companies, politics and bureaucracy gets [sic] in the way of moving fast, from being able to launch an idea and set up a TV campaign it became layers and layers of management," said one ex-Googler. 175 Others noted that the "bet" companies a now controlled more of their own business, adopting hiring and marketing functions. "It gets a little faster, more efficient and a little more independent," said Andy Conrad, CEO of Verily (formerly Google Life Sciences). "I act as a CEO of an independent company instead of a senior executive within a large company." 176 He added, "Sundar [Pichai] will act in the best interests of Google Inc. I will act in the best interests of Google Life Sciences." 177 In support of this view, Porat said the new structure would enable the company to be "an accelerant for entrepreneurship. 178 She added: A lot of that is about giving them the autonomy to operate within this larger family of Alphabet. So what's been very valuable is creating a structure that allows us on the one hand to have maniacal focuses within businesses and at the same time, to continue to plant the seeds and really nurture in a smart way those next engines of growth so that we're not dealing with this question of incrementalism leading to irrelevance. 179 Google insiders commented that the creation of separate bet companies would reduce competition for talent and funds between units. 180 In November 2015, the Wall Street Journal reported that Alphabet would charge Other Bets subsidiaries for corporation-wide services such as computing, recruiting, and marketing. "The people familiar with the matter said executives hope to make the bet companies more accountable for their costs, which may lead to more caution on spending," the newspaper reported. 181 The Economist offered a summary: "Alphabet is grappling with a problem that has already troubled many other big tech firms: how much freedom, money and time to give internal startups." 182 Alphabet Spells a New Google Q4 Earnings Released Alphabet's 2015 fourth-quarter earnings were strong. Total revenue was $21.3 billion, an increase of 18% over the previous year and 14% above the previous quarter (refer to Exhibit 1a). 183 Porat credited mobile search, YouTube, and programmatic advertising for revenue gains. "The primary driver was the increased use of Mobile Search by consumers, benefiting from our ongoing efforts to enhance the efficiency of Mobile Search, as well as from the holiday season," she said. 184 Alphabet was now reporting along two segments: Google and Other Bets, which included "an aggregation of businesses, many of which operate in distinct sectors with different business models," Porat said. Due to certain "idiosyncrasies with respect to the timing of revenue, expenses and CapEx resulting from milestones, partnerships, and other factors," Porat said it would likely be more instructive to evaluate the performance of the Other Bets segment on a 12-month basis. 185 In the Google segment, revenues were $21.2 billion, up 18% over 2014.186 Other Bets, which were grouped together, reported revenues of $448 million, 37% higher than in 2014.187 Porat noted that Nest, Fiber, and Verily generated the majority of Other Bets revenues, adding, "The majority of efforts within Other Bets are pre-revenue." 188 As a whole, Other Bets revenues, sourced from Nest hardware sales, Internet and TV services, and revenues from licensing and R\&D services, made up 0.6% of Alphabet's consolidated revenues. 189 Alphabet reported an operating loss of $3.6 billion in the Other Bets segment for 2015, excluding stock-based compensation, which, Porat said, reflected "the impact of project milestones established several years ago." 190 Looking ahead, she expected Alphabet to continue to pursue "longer-term opportunities both within Google and Other Bets, consistent with our emphasis on pushing the frontier to adjacent areas and moonshots." 191 Nest Nest Labs made Internet-connected thermostats and smoke alarms for what Fadell called "the conscious home." 192 Founded in 2010 by Fadell, a former Apple executive who helped design the iPod, and Matt Rogers, another Apple engineer, Nest released its first smart thermostat in October 2011. 193 The device was an "innovative reimagining of a product category," the New York Times quipped, "a stylish piece of hardware, a circle of brushed stainless steel, reflective polymer and a crystal-sharp color display." 194 In late 2013, Fadell said the thermostat hung in "almost 1\% of U.S. homes." 195 In January 2014, Google acquired Nest for $3.2 billion in the second-largest purchase in the company's history. 196 Fadell said Google would provide Nest financial, legal, and administrative resources that would help them grow. 197 "I was spending so much time in my days just worrying about infrastructure and not worrying about product," Fadell said when the deal was announced. 198 "This allows us to concentrate on the stuff that differentiates us." 199 Roughly six months later, Nest bought Dropcam, a security-camera startup, for $555 million. 200 Between 2011 and 2015, annual revenue growth at Nest surpassed 50%.201 When Alphabet announced plans to restructure, Nest was seen as a beneficiary. As a subsidiary separate from Google, observers said the business would enjoy independence and financial support. 202 During 2015, Nest's revenues totaled $340 million, lagging expectations, according to reports from Recode. 203 By 2016, Nest had 1,100 employees and offered a smart thermostat, a smoke detector, and a security camera. 204 But in March 2016, Fadell told tech news outlet The Information that Alphabet was pressuring noncore divisions to tighten their belts. 205 In his words, Alphabet leadership told its Other Bets subsidiaries, "Show us your business plan for the year. We're going to hold you to those numbers." 206 The Information also reported that 70 employees had left Nest between spring and fall of 2015. 207 Current and former employees complained about Fadell's strict management style and blamed him for product delays. 208 Later that month, Dropcam founder Greg Duffy, who left the company in 2015, expressed his frustration in a public blog post, declaring that it was a "mistake to sell" his startup, which was in the "middle of a record year of sales" when Google acquired it. 209 He faulted Nest for moving slowly. "All of us have worked at big companies before, where it is harder to move fast. But this is something different, as evidenced by the continued lack of output from the currently 1,200person team and its virtually unlimited budget," Duffy wrote. 210 In April, news outlets reported that Nest would be closing Revolv, a company it acquired in 2014. 211 Revolv made devices that could control several smart appliances. 212 "Unfortunately, that means we can't allocate resources to Revolv anymore and we have to shut down the service," Revolv's founders wrote in a blog post. "As of May 15, 2016, your Revolv hub and app will no longer work." 213 Nest said it bought Revolv for the talent, not the products. "We are not fans of yet another hub that people should have to worry about," Rogers said. 214 On June3, 2016, Alphabet said Fadell would leave Nest and move into an advisory role at Google. 215 Observers speculated that Fadell was being let go in light of the complaints lodged against him, but he said the departure had been planned since late 2015. 216 "I don't know of any regrets that I have," he said. "To do what we do at the level we do it, no one's done it before. So you're bound to make mistakes." 217 One observer said a cultural mismatch had ended Fadell's reign. "Nest, with its Apple DNA, was very much a top-down company, where only one person was in charge-Fadell," he wrote. "Google, on the other hand, has an engineer-driven, bottom-up culture." 218 Alphabet chose Marwan Fawaz to replace Fadell. A former Motorola executive, Fawaz was known for his people skills and team-oriented approach. Page said Fawaz would "deepen Nest's partnerships, expand within enterprise channels, and bring Nest products to even more homes." 219 Other Moonshots The creation of Alphabet preceded widespread change also among other divisions formerly operated by Google, including Nest. On August 12, 2015, Google startup Niantic Labs, a game company, announced its independence from Google: "We'll be taking our unique blend of exploration and fun to even bigger audiences with some amazing new partners joining Google as collaborators and backers." 220 In October, Niantic, best known for video game Ingress, announced that it had raised $20 million in backing from Pokmon, Nintendo, and Google. "That's kind of a theme at Google, to take businesses that are not search and give them more independence," said Niantic's founder. "We're kind of at the vanguard of that." 221 In December 2015, Bloomberg reported on Alphabet's plans to turn its self-driving cars unit, which had been contained in X, into a standalone business. 222 In the same month, Verily announced it would create a new company, Verb Surgical Inc., reportedly backed by Johnson \& Johnson and Ethicon, to pursue advances in surgical technology. 223 STAT reported that a dozen senior staff members had left Verily since 2014 amid complaints about the CEO, Andy Conrad. "They said he exaggerates what Verily can deliver, launches big projects on a whim, and rashly diverts resources from prior commitments to the next hot idea that might bring in revenue," STAT reported. "This has led to what they describe as difficult meetings with business partners, and resignations by demoralized engineers and scientists in the face of seemingly impossible demands." 224 Technology analyst Rob Enderle said the premature timing of the employees' departures suggested staffers "are losing confidence in the leadership." 225 In March 2016, Google put robotics firm Boston Dynamics, a 2013 acquisition, up for sale. 226 News reports, citing project insiders, said Google had decided the robots were not close enough to generating revenue. 227 Insiders also cited growing friction between engineers at Boston Dynamics and their Tokyo- and California-based counterparts. 228 According to internal memos, Google executives had become impatient with the slow pace of Boston Dynamics' projects. 229 "We as a startup of our size cannot spend 30-plus percent of our resources on things that take ten years," said one executive during a November 2015 meeting. "There's some time frame that we need to be generating an amount of revenue that covers expenses and [that] needs to be a few years." 230 News outlets also reported that robotics group Replicant was no longer a standalone unit; its employees had been folded into X.231 The moonshot group said it was "defining some specific real world problems in which robotics could help." 232 Looking Ahead As June 2016 came to a close, the future of Nest and other Alphabet moonshots remained uncertain. And despite a concerted effort to diversify, the search engine and its advertising service remained the firm's biggest revenue driver, accounting for nearly 90% of revenues. "In six months, you can say whether the structure has made things better -it has either made them worse or hasn't change [sic] things at all," one analyst concluded. 233 "Being liberated from Google, the moonshots were supposed to thrive under the Alphabet umbrella. Have they? The early results are not good," The Guardian wrote in early June 2016. 234 Others read the departure differently. One observer said leadership change at Nest meant the Alphabet structure was in fact succeeding. She predicted that Nest and Google Home, a Google subsidiary developing a virtual assistant for the home, would succeed: Google's whole motivation for creating the Alphabet holding structure in the first place was to force more financial discipline at its various "moonshots" and other businesses, like Nest, that didn't fit neatly into Google's core focus. It's likely that Alphabet's chief enforcer, CFO Ruth Porat, had a say in deciding that such an important product for the company [home automation] should be fledged elsewhere [within Google Home, a Google subsidiary] - so that it could earn its wings free of the division's drama, financial or otherwise. 235 As the campaign to expand Alphabet's product line continued, Page and Brin had some critical decisions to make about the non-Google subsidiaries. Was it important to give the companies independence or would that strategy empower divisive leadership? How long should Other Bets be allowed to experiment before producing a viable, profitable product? Was Alphabet providing the resources startup ventures desperately needed to succeed, or would the conglomerate structure stifle innovation? Exhibit 1a Alphabet Selected Income Data, Q3 \& Q4 2015 (in millions US\$) Source: Alphabet, Inc., 2015 Annual Report, https:/ / abc.xyz/investor/pdf/20151231_alphabet_10K.pdf, accessed February 2015. Exhibit 1b Alphabet Selected Segment Information, 2013-2015 Exhibit 2 Alphabet, Inc. Share Pricing, Relative to the S\&P 500 Index, August 2004 to June 2016 Source: Alphabet Share Pricing, August 2004 to June 2016, Capital IQ Inc., a division of Standard \& Poor's. Exhibit 3a A Selection of Top Innovations at Bell Labs Exhibit 3b A Selection of Top Innovations at Xerox PARC Source: Todd R. Weiss, "Timeline: PARC Milestones," Computerworld, September 20, 2010, http:/ / www.computerworld.com/ article/2515874/computer-hardware/timeline--parc-milestones.html, accessed June 2016; and Dan Farber, "Tracing the Origins of the Macintosh," CNet, January 21, 2014, http://www.cnet.comews/tracing-the-origins-of-themacintosh/, accessed June 2016. Exhibit 4 Alphabet Inc. Share Pricing, Relative to the S\&P 500 Index, August 2015 to June 2016 Source: Alphabet Share Pricing, August 2015 to June 2016, Capital IQ, Inc., a division of Standard \& Poor's. Exhibit 6 Alphabet's "Other Bets" Companies, 2016 Company Access/Google Fiber Calico Nest Verily GV (formerly Google Ventures) Google Capital X (formerly Google X) Sidewalk Labs Deep Mind Source: Compiled by casewriter from the company websites: calicolabs.com, solvetorx.com, nest.com, gv.com, googlecapital.com, verily.com, sidewalklabs.com, fiber.google.com, and deepmind.com, all accessed February 2016. Note: This is not an exhaustive list of Ot ther Bets ventures

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts