Please read the below case and answer the below questions:

1. If the probability distribution of expected future interest rates was "tight" as opposed to "flat", i.e., if it had a small standard deviation, would this have any effect on the decision to refund now versus waiting? Assume the same expected interest rate in either case. Also, would a skew to the right or a skew to the left, from the same expected rate, make you more likely to recommend an immediate refunding?

2. Suppose the major bond rating agencies downgraded TEI's credit rating from Ba to triple B before the firm could initiate the refunding, and this caused the following changes to data given in the case:

a. The coupon rate on the new bond would be 10.25%

b. The flotation cost on the new bonds would be $1,500,000.

How would these factors affect the refunding decision?

3. What recommendation should george Ramos make to the board?

Thanks!

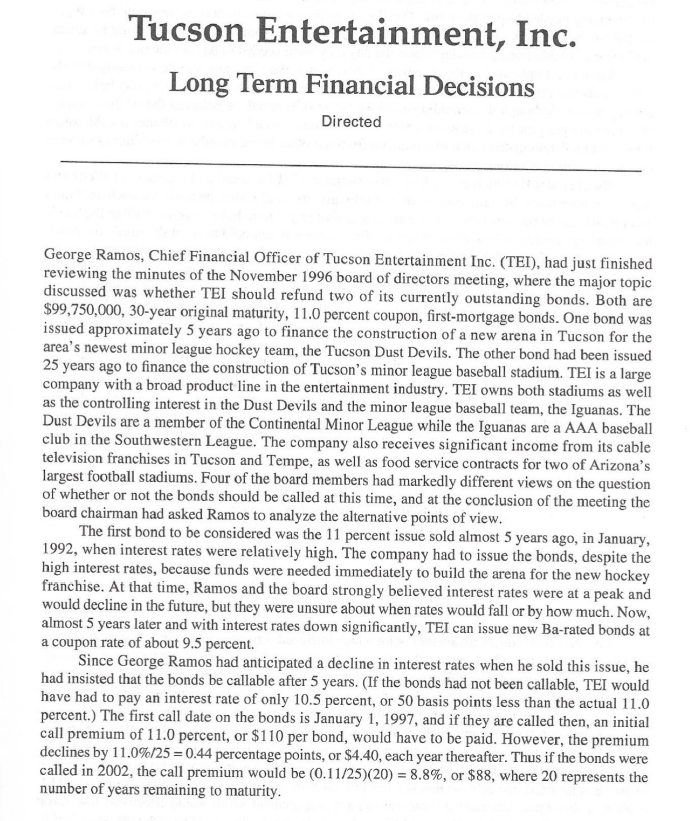

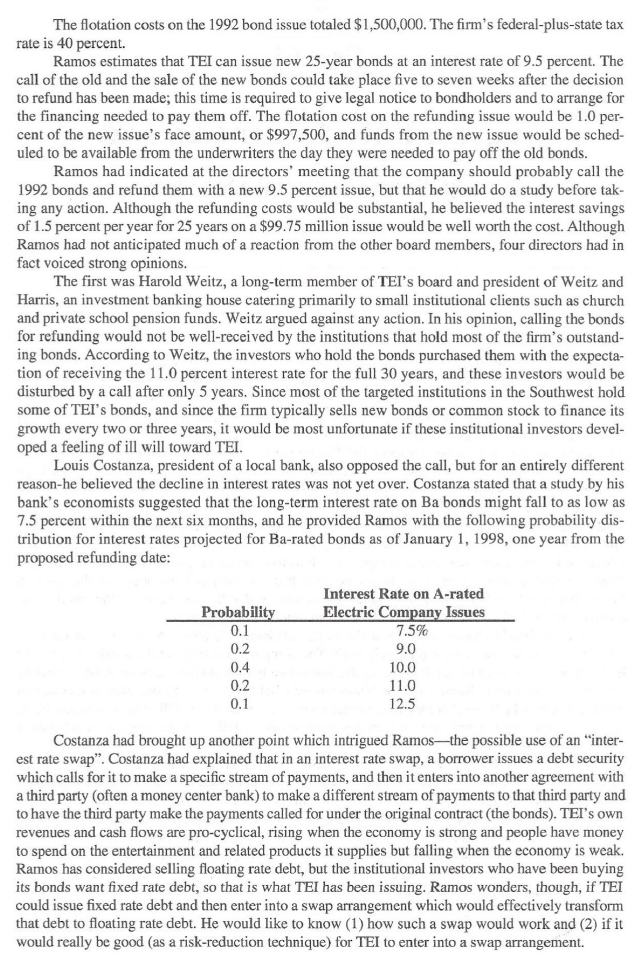

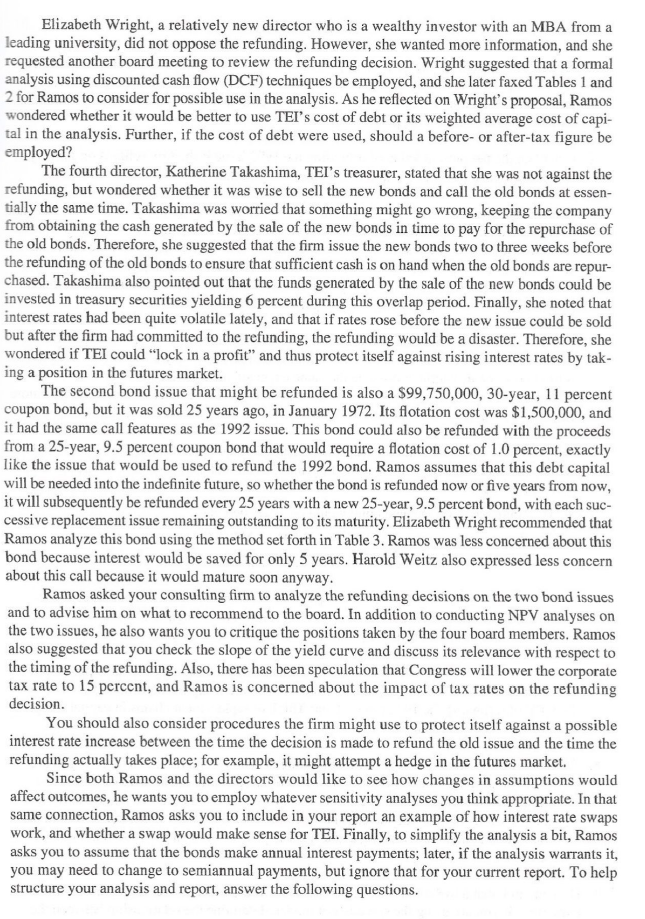

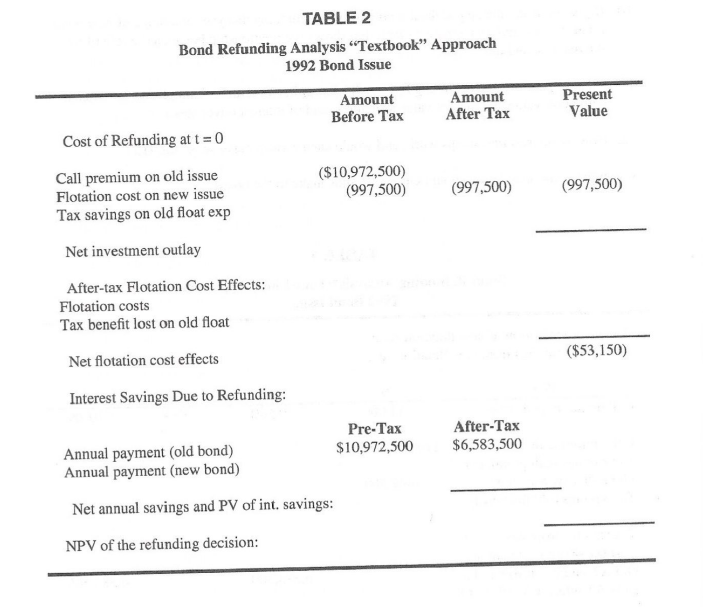

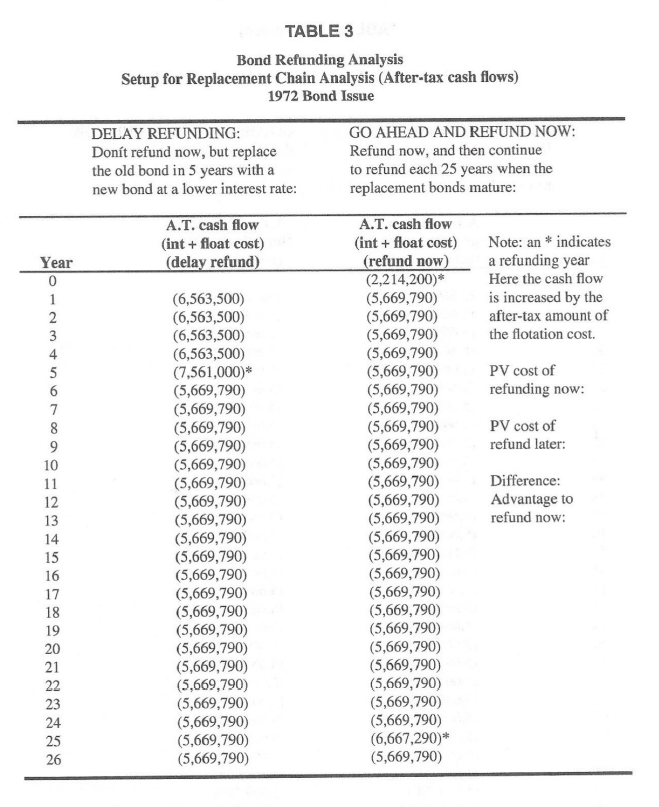

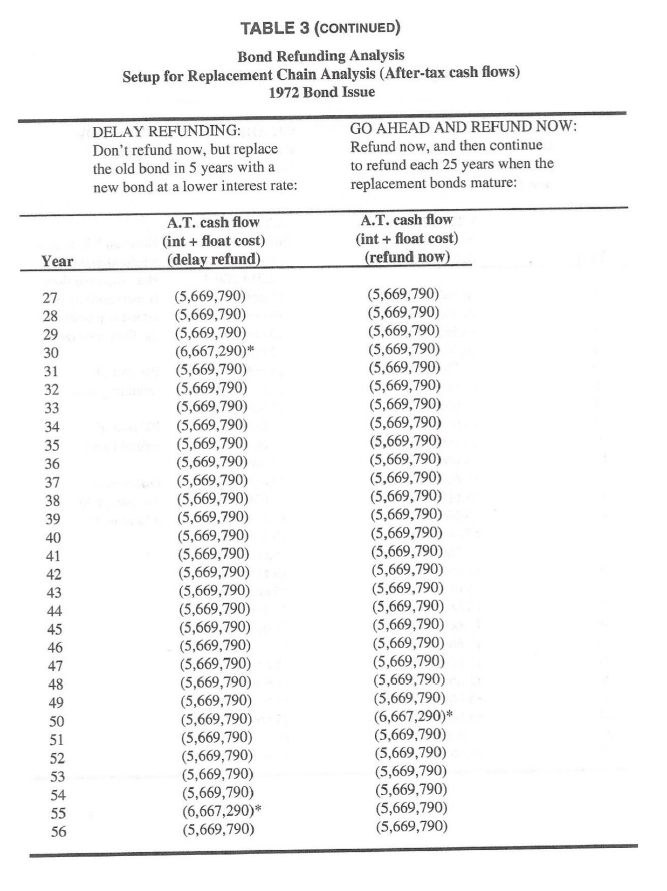

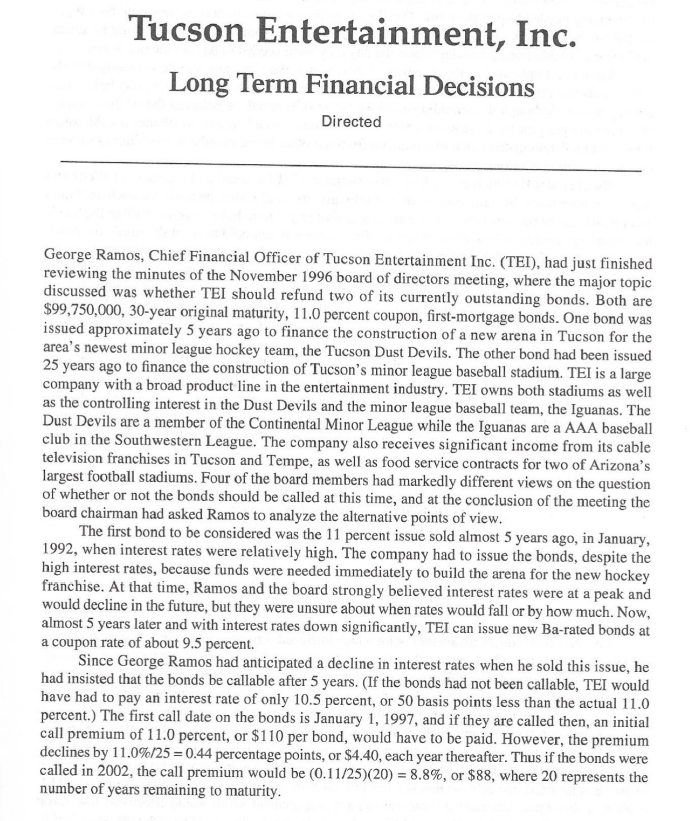

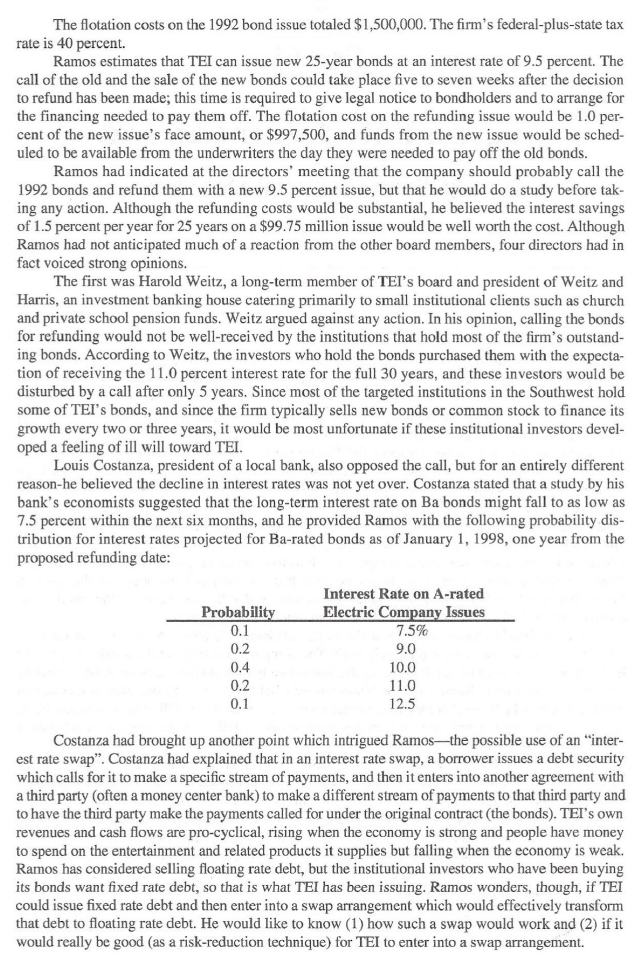

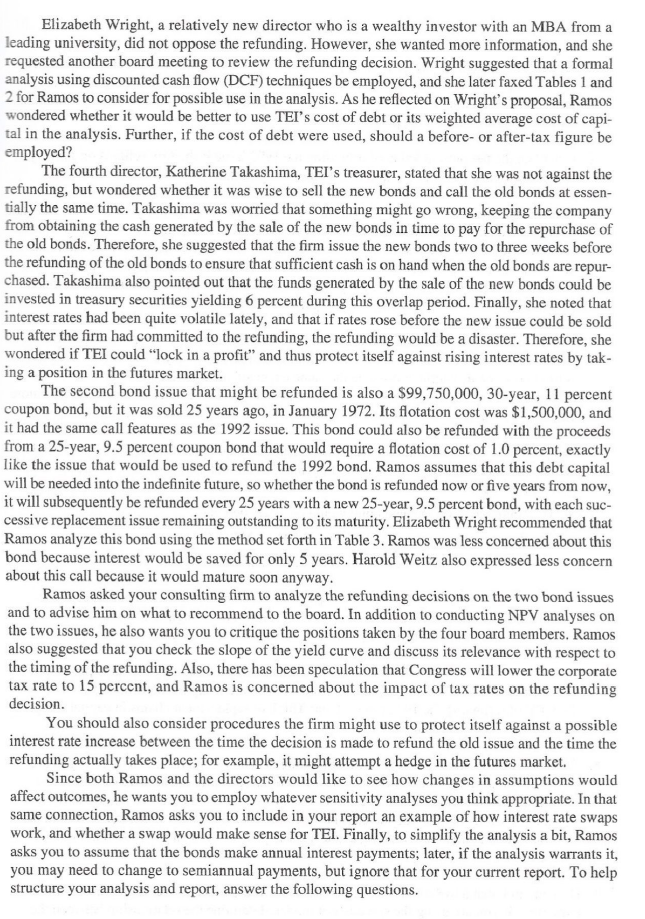

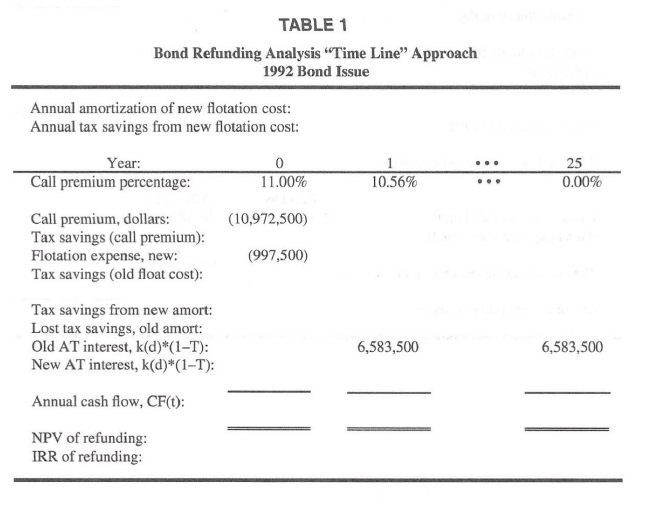

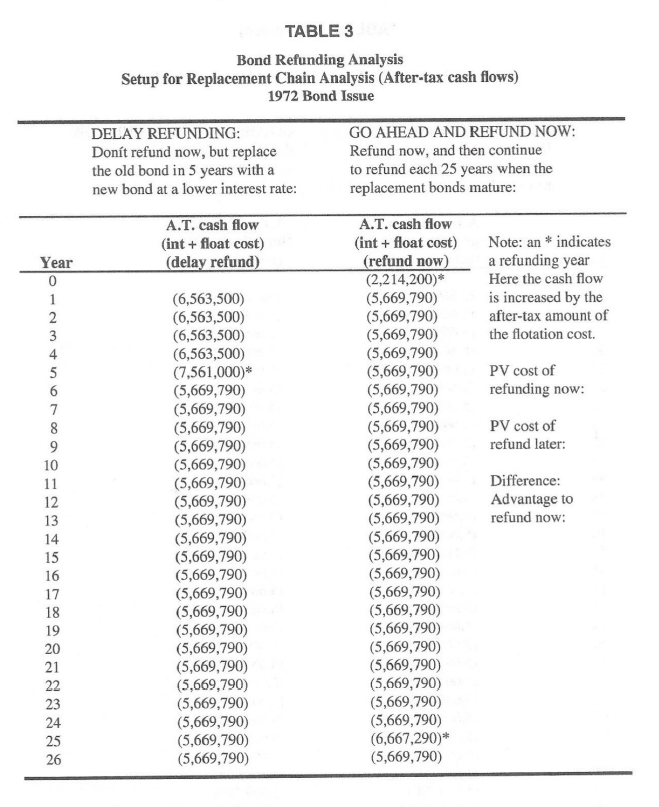

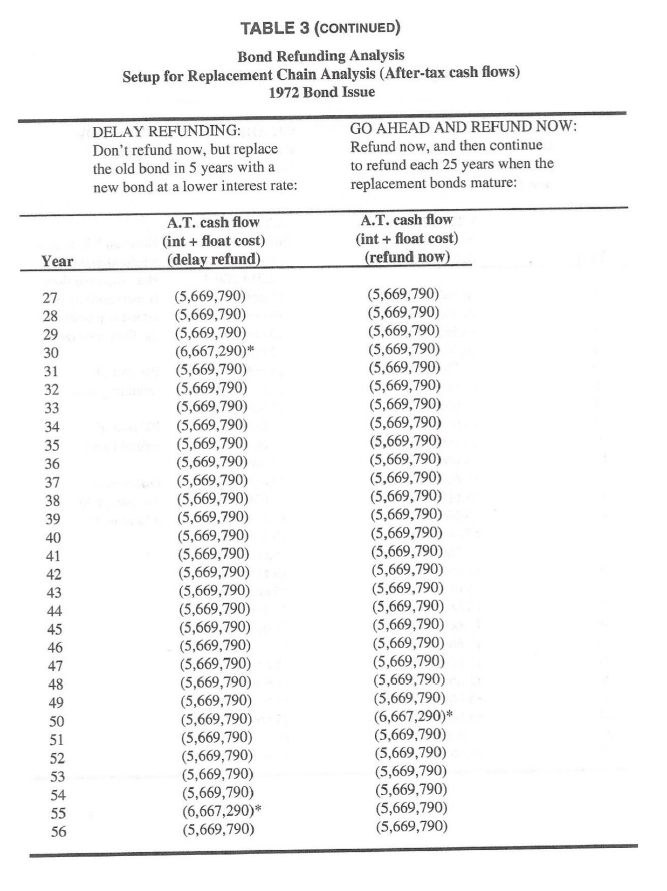

Tucson Entertainment, Inc. Long Term Financial Decisions Directed George Ramos, Chief Financial Officer of Tucson Entertainment Inc. (TEI), had just finished reviewing the minutes of the November 1996 board of directors meeting, where the major topic discussed was whether TEI should refund two of its currently outstanding bonds. Both are $99,750,000, 30-year original maturity, 11.0 percent coupon, first-mortgage bonds. One bond was issued approximately 5 years ago to finance the construction of a new arena in Tucson for the area's newest minor league hockey team, the Tucson Dust Devils. The other bond had been issued 25 years ago to finance the construction of Tucson's minor league baseball stadium. TEI is a large company with a broad product line in the entertainment industry. TEI owns both stadiums as well as the controlling interest in the Dust Devils and the minor league baseball team, the Iguanas. The Dust Devils are a member of the Continental Minor League while the Iguanas are a AAA baseball club in the Southwestern League. The company also receives significant income from its cable television franchises in Tucson and Tempe, as well as food service contracts for two of Arizona's largest football stadiums. Four of the board members had markedly different views on the question of whether or not the bonds should be called at this time, and at the conclusion of the meeting the board chairman had asked Ramos to analyze the alternative points of view. The first bond to be considered was the 11 percent issue sold almost 5 years ago, in January, 1992, when interest rates were relatively high. The company had to issue the bonds, despite the high interest rates, because funds were needed immediately to build the arena for the new hockey franchise. At that time, Ramos and the board strongly believed interest rates were at a peak and would decline in the future, but they were unsure about when rates would fall or by how much. Now, almost 5 years later and with interest rates down significantly, TEI can issue new Ba-rated bonds at a coupon rate of about 9.5 percent. Since George Ramos had anticipated a decline in interest rates when he sold this issue, he had insisted that the bonds be callable after 5 years. (If the bonds had not been callable, TEI would have had to pay an interest rate of only 10.5 percent, or 50 basis points less than the actual 11.0 percent.) The first call date on the bonds is January 1, 1997, and if they are called then, an initial call premium of 11.0 percent, or $110 per bond, would have to be paid. However, the premium declines by 11.0%/25 = 0.44 percentage points, or $4.40, each year thereafter. Thus if the bonds were called in 2002, the call premium would be (0.11/25)(20) = 8.8%, or $88, where 20 represents the number of years remaining to maturity. The flotation costs on the 1992 bond issue totaled $1,500,000. The firm's federal-plus-state tax rate is 40 percent. Ramos estimates that TEI can issue new 25-year bonds at an interest rate of 9.5 percent. The call of the old and the sale of the new bonds could take place five to seven weeks after the decision to refund has been made; this time is required to give legal notice to bondholders and to arrange for the financing needed to pay them off. The flotation cost on the refunding issue would be 1.0 per- cent of the new issue's face amount, or $997,500, and funds from the new issue would be sched- uled to be available from the underwriters the day they were needed to pay off the old bonds. Ramos had indicated at the directors' meeting that the company should probably call the 1992 bonds and refund them with a new 9.5 percent issue, but that he would do a study before tak- ing any action. Although the refunding costs would be substantial, he believed the interest savings of 1.5 percent per year for 25 years on a $99.75 million issue would be well worth the cost. Although Ramos had not anticipated much of a reaction from the other board members, four directors had in fact voiced strong opinions. The first was Harold Weitz, a long-term member of TEI's board and president of Weitz and Harris, an investment banking house catering primarily to small institutional clients such as church and private school pension funds. Weitz argued against any action. In his opinion, calling the bonds for refunding would not be well-received by the institutions that hold most of the firm's outstand- ing bonds. According to Weitz, the investors who hold the bonds purchased them with the expecta- tion of receiving the 11.0 percent interest rate for the full 30 years, and these investors would be disturbed by a call after only 5 years. Since most of the targeted institutions in the Southwest hold some of TEI's bonds, and since the firm typically sells new bonds or common stock to finance its growth every two or three years, it would be most unfortunate if these institutional investors devel- oped a feeling of ill will toward TEI. Louis Costanza, president of a local bank, also opposed the call, but for an entirely different reason he believed the decline in interest rates was not yet over. Costanza stated that a study by his bank's economists suggested that the long-term interest rate on Ba bonds might fall to as low as 7.5 percent within the next six months, and he provided Ramos with the following probability dis- tribution for interest rates projected for Ba-rated bonds as of January 1, 1998, one year from the proposed refunding date: Probability 0.1 0.2 0.4 0.2 0.1 Interest Rate on A-rated Electric Company Issues 7.5% 9.0 10.0 11.0 12.5 Costanza had brought up another point which intrigued Ramosthe possible use of an inter- est rate swap". Costanza had explained that in an interest rate swap, a borrower issues a debt security which calls for it to make a specific stream of payments, and then it enters into another agreement with a third party (often a money center bank) to make a different stream of payments to that third party and to have the third party make the payments called for under the original contract (the bonds). TEI's own revenues and cash flows are pro-cyclical, rising when the economy is strong and people have money to spend on the entertainment and related products it supplies but falling when the economy is weak. Ramos has considered selling floating rate debt, but the institutional investors who have been buying its bonds want fixed rate debt, so that is what TEI has been issuing. Ramos wonders, though, if TEI could issue fixed rate debt and then enter into a swap arrangement which would effectively transform that debt to floating rate debt. He would like to know (1) how such a swap would work and (2) if it would really be good (as a risk-reduction technique) for TEI to enter into a swap arrangement. Elizabeth Wright, a relatively new director who is a wealthy investor with an MBA from a leading university, did not oppose the refunding. However, she wanted more information, and she requested another board meeting to review the refunding decision. Wright suggested that a formal analysis using discounted cash flow (DCF) techniques be employed, and she later faxed Tables 1 and 2 for Ramos to consider for possible use in the analysis. As he reflected on Wright's proposal, Ramos wondered whether it would be better to use TEI's cost of debt or its weighted average cost of capi- tal in the analysis. Further, if the cost of debt were used, should a before- or after-tax figure be employed? The fourth director, Katherine Takashima, TEI's treasurer, stated that she was not against the refunding, but wondered whether it was wise to sell the new bonds and call the old bonds at essen- tially the same time. Takashima was worried that something might go wrong, keeping the company from obtaining the cash generated by the sale of the new bonds in time to pay for the repurchase of the old bonds. Therefore, she suggested that the firm issue the new bonds two to three weeks before the refunding of the old bonds to ensure that sufficient cash is on hand when the old bonds are repur- chased. Takashima also pointed out that the funds generated by the sale of the new bonds could be invested in treasury securities yielding 6 percent during this overlap period. Finally, she noted that interest rates had been quite volatile lately, and that if rates rose before the new issue could be sold but after the firm had committed to the refunding, the refunding would be a disaster. Therefore, she wondered if TEI could "lock in a profit" and thus protect itself against rising interest rates by tak- ing a position in the futures market. The second bond issue that might be refunded is also a $99,750,000, 30-year, 11 percent coupon bond, but it was sold 25 years ago, in January 1972. Its flotation cost was $1,500,000, and it had the same call features as the 1992 issue. This bond could also be refunded with the proceeds from a 25-year, 9.5 percent coupon bond that would require a flotation cost of 1.0 percent, exactly like the issue that would be used to refund the 1992 bond. Ramos assumes that this debt capital will be needed into the indefinite future, so whether the bond is refunded now or five years from now, it will subsequently be refunded every 25 years with a new 25-year, 9.5 percent bond, with each suc- cessive replacement issue remaining outstanding to its maturity. Elizabeth Wright recommended that Ramos analyze this bond using the method set forth in Table 3. Ramos was less concerned about this bond because interest would be saved for only 5 years. Harold Weitz also expressed less concern about this call because it would mature soon anyway. Ramos asked your consulting firm to analyze the refunding decisions on the two bond issues and to advise him on what to recommend to the board. In addition to conducting NPV analyses on the two issues, he also wants you to critique the positions taken by the four board members. Ramos also suggested that you check the slope of the yield curve and discuss its relevance with respect to the timing of the refunding. Also, there has been speculation that Congress will lower the corporate tax rate to 15 percent, and Ramos is concerned about the impact of tax rates on the refunding decision. You should also consider procedures the firm might use to protect itself against a possible interest rate increase between the time the decision is made to refund the old issue and the time the refunding actually takes place; for example, it might attempt a hedge in the futures market. Since both Ramos and the directors would like to see how changes in assumptions would affect outcomes, he wants you to employ whatever sensitivity analyses you think appropriate. In that same connection, Ramos asks you to include in your report an example of how interest rate swaps work, and whether a swap would make sense for TEI. Finally, to simplify the analysis a bit, Ramos asks you to assume that the bonds make annual interest payments; later, if the analysis warrants it, you may need to change to semiannual payments, but ignore that for your current report. To help structure your analysis and report, answer the following questions. TABLE 1 Bond Refunding Analysis "Time Line" Approach 1992 Bond Issue Annual amortization of new flotation cost: Annual tax savings from new flotation cost: Year: Call premium percentage: 25 2600 11.00% 10.56% 10.56% 0.00% (10,972,500) Call premium, dollars: Tax savings (call premium): Flotation expense, new: Tax savings (old float cost): (997,500) Tax savings from new amort: Lost tax savings, old amort: Old AT interest, k(d)*(1-T): New AT interest, k(d)*(1-T): 6,583,500 6,583,500 Annual cash flow, CF(t): NPV of refunding: IRR of refunding: TABLE 2 Bond Refunding Analysis Textbook Approach 1992 Bond Issue Amount Before Tax Amount After Tax Present Value Cost of Refunding at t = 0 Call premium on old issue Flotation cost on new issue Tax savings on old float exp ($10,972,500) (997,500) (997,500) (997,500) Net investment outlay After-tax Flotation Cost Effects: Flotation costs Tax benefit lost on old float Net flotation cost effects ($53,150) Interest Savings Due to Refunding: Pre-Tax $10,972,500 After-Tax $6,583,500 Annual payment (old bond) Annual payment (new bond) Net annual savings and PV of int. savings: NPV of the refunding decision: TABLE 3 Bond Refunding Analysis Setup for Replacement Chain Analysis (After-tax cash flows) 1972 Bond Issue DELAY REFUNDING: Dont refund now, but replace the old bond in 5 years with a new bond at a lower interest rate: GO AHEAD AND REFUND NOW: Refund now, and then continue to refund each 25 years when the replacement bonds mature: A.T. cash flow (int + float cost) (delay refund) Year Note: an * indicates a refunding year Here the cash flow is increased by the after-tax amount of the flotation cost. PV cost of refunding now: PV cost of refund later: A.T. cash flow (int + float cost) (refund now) (2,214,200) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (6,667,290)* (5,669,790) (6,563,500) (6,563,500) (6,563,500) (6,563,500) (7,561,000)* (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) Difference: Advantage to refund now: TABLE 3 (CONTINUED) Bond Refunding Analysis Setup for Replacement Chain Analysis (After-tax cash flows) 1972 Bond Issue DELAY REFUNDING: Don't refund now, but replace the old bond in 5 years with a new bond at a lower interest rate: GO AHEAD AND REFUND NOW: Refund now, and then continue to refund each 25 years when the replacement bonds mature: A.T. cash flow (int + float cost) (delay refund) A.T. cash flow (int + float cost) (refund now) Year (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (6,667,290)* (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (6,667,290)* (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669, 790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (6,667,290)* (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) Tucson Entertainment, Inc. Long Term Financial Decisions Directed George Ramos, Chief Financial Officer of Tucson Entertainment Inc. (TEI), had just finished reviewing the minutes of the November 1996 board of directors meeting, where the major topic discussed was whether TEI should refund two of its currently outstanding bonds. Both are $99,750,000, 30-year original maturity, 11.0 percent coupon, first-mortgage bonds. One bond was issued approximately 5 years ago to finance the construction of a new arena in Tucson for the area's newest minor league hockey team, the Tucson Dust Devils. The other bond had been issued 25 years ago to finance the construction of Tucson's minor league baseball stadium. TEI is a large company with a broad product line in the entertainment industry. TEI owns both stadiums as well as the controlling interest in the Dust Devils and the minor league baseball team, the Iguanas. The Dust Devils are a member of the Continental Minor League while the Iguanas are a AAA baseball club in the Southwestern League. The company also receives significant income from its cable television franchises in Tucson and Tempe, as well as food service contracts for two of Arizona's largest football stadiums. Four of the board members had markedly different views on the question of whether or not the bonds should be called at this time, and at the conclusion of the meeting the board chairman had asked Ramos to analyze the alternative points of view. The first bond to be considered was the 11 percent issue sold almost 5 years ago, in January, 1992, when interest rates were relatively high. The company had to issue the bonds, despite the high interest rates, because funds were needed immediately to build the arena for the new hockey franchise. At that time, Ramos and the board strongly believed interest rates were at a peak and would decline in the future, but they were unsure about when rates would fall or by how much. Now, almost 5 years later and with interest rates down significantly, TEI can issue new Ba-rated bonds at a coupon rate of about 9.5 percent. Since George Ramos had anticipated a decline in interest rates when he sold this issue, he had insisted that the bonds be callable after 5 years. (If the bonds had not been callable, TEI would have had to pay an interest rate of only 10.5 percent, or 50 basis points less than the actual 11.0 percent.) The first call date on the bonds is January 1, 1997, and if they are called then, an initial call premium of 11.0 percent, or $110 per bond, would have to be paid. However, the premium declines by 11.0%/25 = 0.44 percentage points, or $4.40, each year thereafter. Thus if the bonds were called in 2002, the call premium would be (0.11/25)(20) = 8.8%, or $88, where 20 represents the number of years remaining to maturity. The flotation costs on the 1992 bond issue totaled $1,500,000. The firm's federal-plus-state tax rate is 40 percent. Ramos estimates that TEI can issue new 25-year bonds at an interest rate of 9.5 percent. The call of the old and the sale of the new bonds could take place five to seven weeks after the decision to refund has been made; this time is required to give legal notice to bondholders and to arrange for the financing needed to pay them off. The flotation cost on the refunding issue would be 1.0 per- cent of the new issue's face amount, or $997,500, and funds from the new issue would be sched- uled to be available from the underwriters the day they were needed to pay off the old bonds. Ramos had indicated at the directors' meeting that the company should probably call the 1992 bonds and refund them with a new 9.5 percent issue, but that he would do a study before tak- ing any action. Although the refunding costs would be substantial, he believed the interest savings of 1.5 percent per year for 25 years on a $99.75 million issue would be well worth the cost. Although Ramos had not anticipated much of a reaction from the other board members, four directors had in fact voiced strong opinions. The first was Harold Weitz, a long-term member of TEI's board and president of Weitz and Harris, an investment banking house catering primarily to small institutional clients such as church and private school pension funds. Weitz argued against any action. In his opinion, calling the bonds for refunding would not be well-received by the institutions that hold most of the firm's outstand- ing bonds. According to Weitz, the investors who hold the bonds purchased them with the expecta- tion of receiving the 11.0 percent interest rate for the full 30 years, and these investors would be disturbed by a call after only 5 years. Since most of the targeted institutions in the Southwest hold some of TEI's bonds, and since the firm typically sells new bonds or common stock to finance its growth every two or three years, it would be most unfortunate if these institutional investors devel- oped a feeling of ill will toward TEI. Louis Costanza, president of a local bank, also opposed the call, but for an entirely different reason he believed the decline in interest rates was not yet over. Costanza stated that a study by his bank's economists suggested that the long-term interest rate on Ba bonds might fall to as low as 7.5 percent within the next six months, and he provided Ramos with the following probability dis- tribution for interest rates projected for Ba-rated bonds as of January 1, 1998, one year from the proposed refunding date: Probability 0.1 0.2 0.4 0.2 0.1 Interest Rate on A-rated Electric Company Issues 7.5% 9.0 10.0 11.0 12.5 Costanza had brought up another point which intrigued Ramosthe possible use of an inter- est rate swap". Costanza had explained that in an interest rate swap, a borrower issues a debt security which calls for it to make a specific stream of payments, and then it enters into another agreement with a third party (often a money center bank) to make a different stream of payments to that third party and to have the third party make the payments called for under the original contract (the bonds). TEI's own revenues and cash flows are pro-cyclical, rising when the economy is strong and people have money to spend on the entertainment and related products it supplies but falling when the economy is weak. Ramos has considered selling floating rate debt, but the institutional investors who have been buying its bonds want fixed rate debt, so that is what TEI has been issuing. Ramos wonders, though, if TEI could issue fixed rate debt and then enter into a swap arrangement which would effectively transform that debt to floating rate debt. He would like to know (1) how such a swap would work and (2) if it would really be good (as a risk-reduction technique) for TEI to enter into a swap arrangement. Elizabeth Wright, a relatively new director who is a wealthy investor with an MBA from a leading university, did not oppose the refunding. However, she wanted more information, and she requested another board meeting to review the refunding decision. Wright suggested that a formal analysis using discounted cash flow (DCF) techniques be employed, and she later faxed Tables 1 and 2 for Ramos to consider for possible use in the analysis. As he reflected on Wright's proposal, Ramos wondered whether it would be better to use TEI's cost of debt or its weighted average cost of capi- tal in the analysis. Further, if the cost of debt were used, should a before- or after-tax figure be employed? The fourth director, Katherine Takashima, TEI's treasurer, stated that she was not against the refunding, but wondered whether it was wise to sell the new bonds and call the old bonds at essen- tially the same time. Takashima was worried that something might go wrong, keeping the company from obtaining the cash generated by the sale of the new bonds in time to pay for the repurchase of the old bonds. Therefore, she suggested that the firm issue the new bonds two to three weeks before the refunding of the old bonds to ensure that sufficient cash is on hand when the old bonds are repur- chased. Takashima also pointed out that the funds generated by the sale of the new bonds could be invested in treasury securities yielding 6 percent during this overlap period. Finally, she noted that interest rates had been quite volatile lately, and that if rates rose before the new issue could be sold but after the firm had committed to the refunding, the refunding would be a disaster. Therefore, she wondered if TEI could "lock in a profit" and thus protect itself against rising interest rates by tak- ing a position in the futures market. The second bond issue that might be refunded is also a $99,750,000, 30-year, 11 percent coupon bond, but it was sold 25 years ago, in January 1972. Its flotation cost was $1,500,000, and it had the same call features as the 1992 issue. This bond could also be refunded with the proceeds from a 25-year, 9.5 percent coupon bond that would require a flotation cost of 1.0 percent, exactly like the issue that would be used to refund the 1992 bond. Ramos assumes that this debt capital will be needed into the indefinite future, so whether the bond is refunded now or five years from now, it will subsequently be refunded every 25 years with a new 25-year, 9.5 percent bond, with each suc- cessive replacement issue remaining outstanding to its maturity. Elizabeth Wright recommended that Ramos analyze this bond using the method set forth in Table 3. Ramos was less concerned about this bond because interest would be saved for only 5 years. Harold Weitz also expressed less concern about this call because it would mature soon anyway. Ramos asked your consulting firm to analyze the refunding decisions on the two bond issues and to advise him on what to recommend to the board. In addition to conducting NPV analyses on the two issues, he also wants you to critique the positions taken by the four board members. Ramos also suggested that you check the slope of the yield curve and discuss its relevance with respect to the timing of the refunding. Also, there has been speculation that Congress will lower the corporate tax rate to 15 percent, and Ramos is concerned about the impact of tax rates on the refunding decision. You should also consider procedures the firm might use to protect itself against a possible interest rate increase between the time the decision is made to refund the old issue and the time the refunding actually takes place; for example, it might attempt a hedge in the futures market. Since both Ramos and the directors would like to see how changes in assumptions would affect outcomes, he wants you to employ whatever sensitivity analyses you think appropriate. In that same connection, Ramos asks you to include in your report an example of how interest rate swaps work, and whether a swap would make sense for TEI. Finally, to simplify the analysis a bit, Ramos asks you to assume that the bonds make annual interest payments; later, if the analysis warrants it, you may need to change to semiannual payments, but ignore that for your current report. To help structure your analysis and report, answer the following questions. TABLE 1 Bond Refunding Analysis "Time Line" Approach 1992 Bond Issue Annual amortization of new flotation cost: Annual tax savings from new flotation cost: Year: Call premium percentage: 25 2600 11.00% 10.56% 10.56% 0.00% (10,972,500) Call premium, dollars: Tax savings (call premium): Flotation expense, new: Tax savings (old float cost): (997,500) Tax savings from new amort: Lost tax savings, old amort: Old AT interest, k(d)*(1-T): New AT interest, k(d)*(1-T): 6,583,500 6,583,500 Annual cash flow, CF(t): NPV of refunding: IRR of refunding: TABLE 2 Bond Refunding Analysis Textbook Approach 1992 Bond Issue Amount Before Tax Amount After Tax Present Value Cost of Refunding at t = 0 Call premium on old issue Flotation cost on new issue Tax savings on old float exp ($10,972,500) (997,500) (997,500) (997,500) Net investment outlay After-tax Flotation Cost Effects: Flotation costs Tax benefit lost on old float Net flotation cost effects ($53,150) Interest Savings Due to Refunding: Pre-Tax $10,972,500 After-Tax $6,583,500 Annual payment (old bond) Annual payment (new bond) Net annual savings and PV of int. savings: NPV of the refunding decision: TABLE 3 Bond Refunding Analysis Setup for Replacement Chain Analysis (After-tax cash flows) 1972 Bond Issue DELAY REFUNDING: Dont refund now, but replace the old bond in 5 years with a new bond at a lower interest rate: GO AHEAD AND REFUND NOW: Refund now, and then continue to refund each 25 years when the replacement bonds mature: A.T. cash flow (int + float cost) (delay refund) Year Note: an * indicates a refunding year Here the cash flow is increased by the after-tax amount of the flotation cost. PV cost of refunding now: PV cost of refund later: A.T. cash flow (int + float cost) (refund now) (2,214,200) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (6,667,290)* (5,669,790) (6,563,500) (6,563,500) (6,563,500) (6,563,500) (7,561,000)* (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) Difference: Advantage to refund now: TABLE 3 (CONTINUED) Bond Refunding Analysis Setup for Replacement Chain Analysis (After-tax cash flows) 1972 Bond Issue DELAY REFUNDING: Don't refund now, but replace the old bond in 5 years with a new bond at a lower interest rate: GO AHEAD AND REFUND NOW: Refund now, and then continue to refund each 25 years when the replacement bonds mature: A.T. cash flow (int + float cost) (delay refund) A.T. cash flow (int + float cost) (refund now) Year (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (6,667,290)* (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (6,667,290)* (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669, 790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (6,667,290)* (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790) (5,669,790)