Please read the case and answer to at least 1-2 questions.

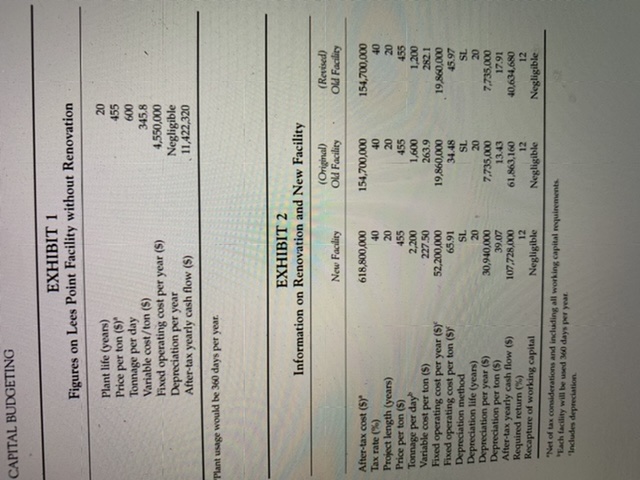

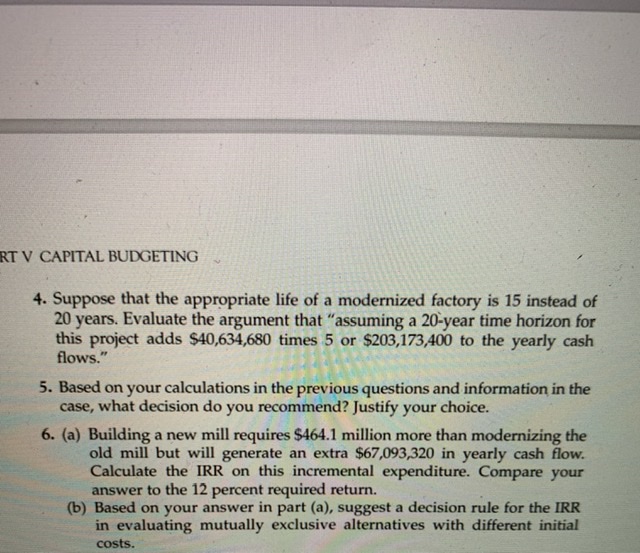

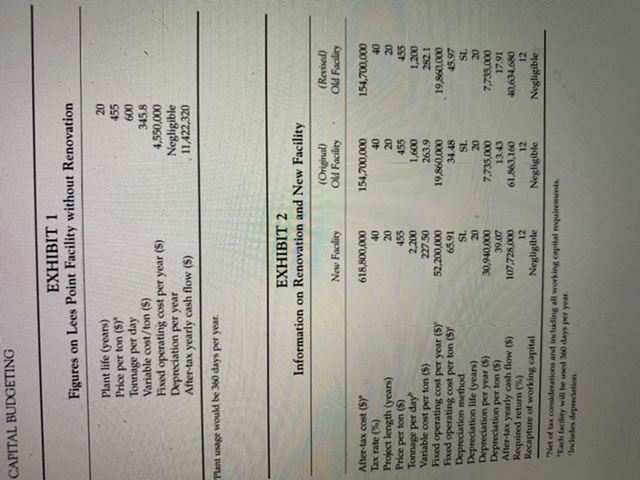

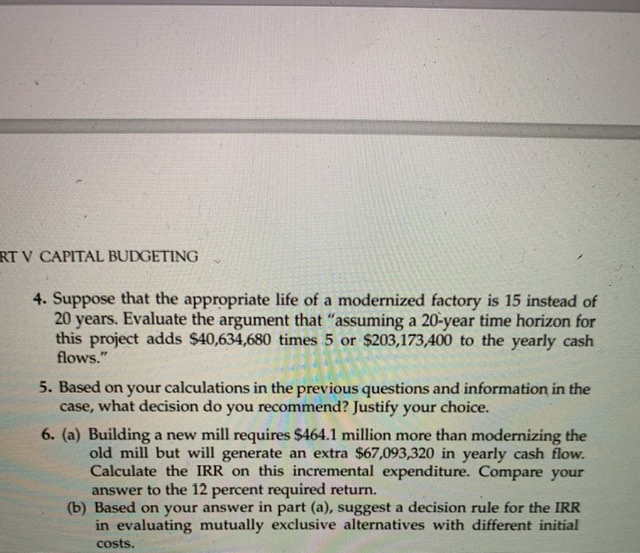

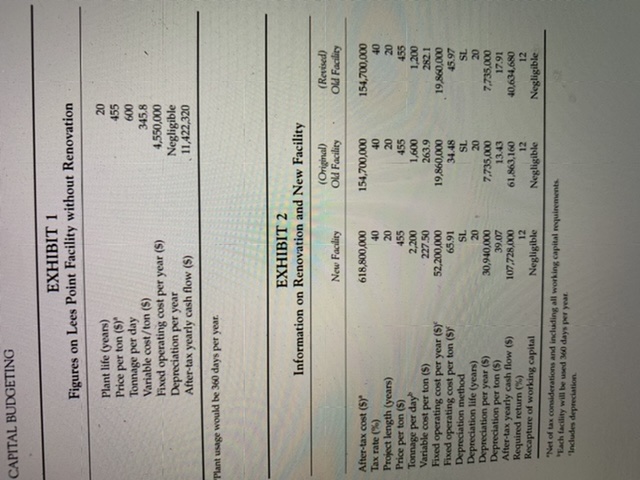

PART V CAPITAL BUDGETING At present (1996) the EC is considering two alternatives for achieving a much-needed increase in the firm's production capacity. One option involves modernizing an existing mill in Lees Point, North Carolina. If the plant is not renovated in the near future, production would drop to 600 tons per day and the yearly cash flow would be $11,422,320. (See Exhibit 1 for more complete information). The other alternative is to build a new mill at Midtown, North Carolina, which is 15 miles from Lees Point. Barbara Wadkins, a member of the EC, was responsible for estimating the cost and yearly cash flows from building the new paper mill at Midtown. She calculated the cost to be $618.8 million net of any tax considerations and include ing working capital, and estimated the yearly after-tax cash flow to be $107,728,000. Exhibit 2 presents the information used to determine these fig- ures. All committee members agree that these numbers are "quite reasonable." CONTROVERSY The figures on modernizing the existing facility at Lees Point are more contro- versial, however. Information on this project was originally sent by the man- agement of the Lees Point plant and is also presented in Exhibit 2. The controversy centers on the estimated tonnage per day of the plant and its per- unit variable cost. Wadkins politely pointed out that it would be "extremely difficult for an old facility like the one at Lees Point to achieve output of 1,600 tons per day." In contrast to Wadkins's mild reaction was Kurzer's angry response. "You can forget it! I'll be the NBA's MVP before that plant puts out that tonnage!" Everyone on the EC knew what the problem was. Management is from Lets Point and is worried that a new facility will reduce jobs. "I don't know why I got so angry. I should expect an estimate like this," said Kurzer. After much discussion the committee unanimously agreed that 1,200 tons per day was much more accurate and, if anything, a bit optimistic. It was also decided that a per-unit variable cost of $282.1 per ton was appropriate instead of the original figure of $263.9 per ton. With these changes the yearly cash flow after taxes was estimated to be $40,634,680; this was considerably lower than the projection of $61,863,160 based on the figures sent by Lees Point management. MORE CONTROVERSY Both projects are assumed to last 20 years, This is a relatively long time horizon for a capital budgeting project, but the company feels a paper mill is unlikely to become technologically obsolete since paper production techniques have changed very little in the last century. At least one EC member, however, thinksRT V CAPITAL BUDGETING 4. Suppose that the appropriate life of a modernized factory is 15 instead of 20 years. Evaluate the argument that "assuming a 20-year time horizon for this project adds $40,634,680 times 5 or $203,173,400 to the yearly cash flows." 5. Based on your calculations in the previous questions and information in the case, what decision do you recommend? Justify your choice. 6. (a) Building a new mill requires $464.1 million more than modernizing the old mill but will generate an extra $67,093,320 in yearly cash flow. Calculate the IRR on this incremental expenditure. Compare your answer to the 12 percent required return. (b) Based on your answer in part (a), suggest a decision rule for the IRR in evaluating mutually exclusive alternatives with different initial costs.CAPITAL BUDGETING EXHIBIT 1 Figures on Lees Point Facility without Renovation Plant life (years) Price per ton (S) 455 Tonnage per day 600 Variable cost/ton (S) 345.8 Fixed operating cost per year ($) 4,550,000 Depreciation per year Negligible After-tax yearly cash flow (S) 11,422,320 Plant usage would be 360 days per year. EXHIBIT 2 Information on Renovation and New Facility (Original) (Revised) New Facility OW Facility Old Facility After-tax cost ($)" 618,800,000 154,700,000 154,700,000 Tax rate ( ) Project length (years) 20 Price per ton (S) 455 455 455 Tonnage per day 2,200 1,600 1,200 Variable cost per ton (S) 227.50 263.9 282.1 Fixed operating cost per year ($) 52,200,000 19,860,000 19,860,000 Fixed operating cost per ton ($) 65.91 34.48 45.97 Depreciation method Depreciation life (years) Depreciation per year ($) Depreciation per ton ($) 30,940,000 7,735,000 7,735,000 After-tax yearly cash flow (S) 39.07 13.43 17.91 Required return (%) 107,728,000 61,863,160 40,634,650 Recapture of working capital Negligible 12 12 Negligible Negligible "Niel of tax coralderations and including all working capital requirements "Each facility will be used Mol days per prat "Includes depreciationCASE 20 FORT GREENWOLD 125 that a 20-year period is too long for the "modernize-the-old" option. Past expe rience, he argues, indicates that revitalizing an existing facility will rarely extend its life that much, and 15 years seems more probable. If so, he wonders if "we aren't being extremely charitable to the Lees Point plant. By my calcula- tions, assuming a 20-year time horizon for this project adds $40,634,680 times 5 or $203,173,400 to the total yearly cash flows. That's some largesse!" The rest of the committee concedes that 20 years may be a bit long, but decides to retain this time period as a working hypothesis. EMPLOYEE CONCERNS Some EC members are worried about the impact on employee morale if the fac- tory is relocated. "Apparently," says Wadkins, "there is considerable opposition to closing down the old factory, judging from the inaccurate figures we received." It is noted, however, that the move will "most certainly" not cost any-one a job, but will, in fact, create new positions, including some.relatively high-paying managerial ones. Nonetheless, it was obvious that the proposed relocation would impose costs on the employees. Many would either have to relocate to Midtown or face a 30-mile round trip daily commute. Wadkins won- dered if it "was fair and appropriate" to ask the employees to bear such costs, especially in light of the remarkable loyalty the Lees Point employees had shown to the company. She notes that a large proportion of the employees have worked for FG for more than 10 years. "One thing is clear," remarks a subdued Kurzer. "If we choose to relocate the plant, it is important that it does not appear to be some type of ivory-tower decision that would be inconsistent with the management philosophy we've promoted all these years. Barbara, I am sensitive to the issues you bring up. Employee morale and employee loyalty are very important considerations. Maybe we could work something out-you know, like some type of moving allowance." Kurzer also reminded the committee that Midtown was the closest suitable site to Lees Point should the company move.CASE 20 FORT GREENWOLD CAPITAL BUDGETING The public image of business in the latter part of the nineteenth century was hardly flattering- The adventures of so-called "Robber Barons" constantly made the headlines and their exploits matched those of their contemporaries in the Wild West. For example, J. P. Morgan hired an army of toughs to literally battle for a section of railroad near Binghamton, New York. And business leaders often expressed their contempt for the public interest, exemplified by such infamous comments as W. H. Vanderbilt's "the public be damned" and J. P. Morgan's "I owe the public nothing." Recent research suggests that these individuals were probably not the villains they were portrayed to be, though it is undeniable that they wielded enormous power. It was precisely during the era of these powerful business leaders that Harold Cole founded Fort Greenwold (FG), a firm that is currently one of the largest producers of paper and pulp with annual sales of $3.5 billion. Cole located his first plant in a rural town in New England, partly to create jobs for the many unemployed workers in the area. "Having a heart does not mean you can't make a buck," Harold was fond of saying. The firm has always been active in the affairs of the community and donates generously to local civic and char- itable organizations. It also takes special pride in promoting a family atmos- phere among its employees. Personnel experts believe that these policies are largely responsible for the enviable productivity record of FG's workers. For its first 80 years FG had an impressive record of growth in earnings and sales. But as the company grew, the willingness of top-level management to decentralize and delegate authority did not. The company stagnated until the appointment of Andy Kurzer as chairman eight years ago in 1988. Kurzer was shocked at the "nickel-and-dime stuff" that reached corporate headquarters, and he moved quickly to decentralize authority. One major change involved the company's capital budgeting procedures. FG actually had no formal mechanism for capital projects. Kurzer changed this and set up a six-person expenditures committee (EC) that would decide projects costing more than $200,000. Smaller expenditures would be decided at the regional and local levels