Question: Please read the questions Question: 1. ) Share a time when you witnessed or experienced deficit model thinking in the classroom AND/OR share an example

Please read the questions

Question: 1. ) Share a time when you witnessed or experienced deficit model thinking in the classroom AND/OR share an example of a time when you witnessed or experienced an asset or strength-based approach in the classroom. What happened? How did you or other students react? How did it make you feel about learning or school?

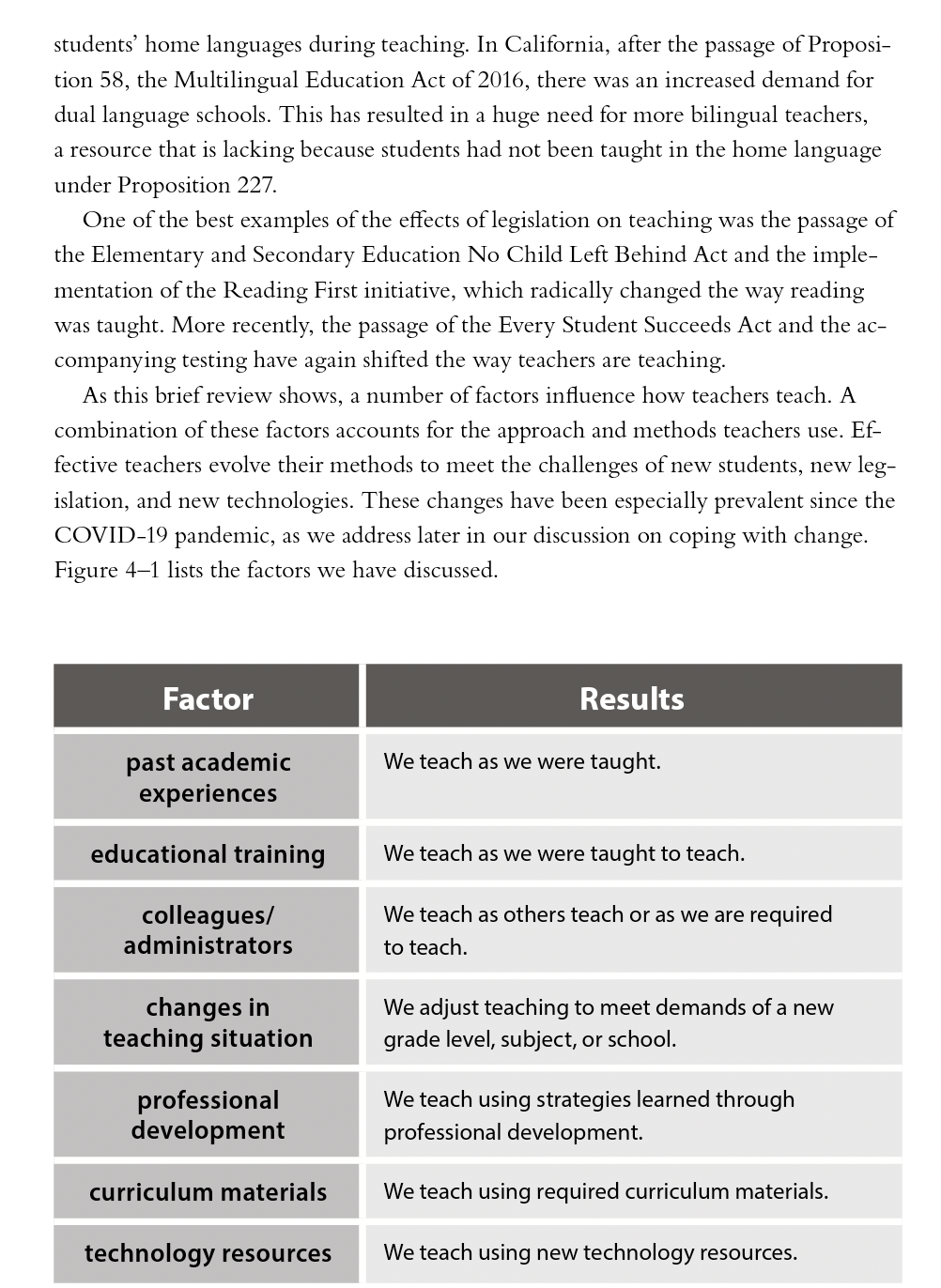

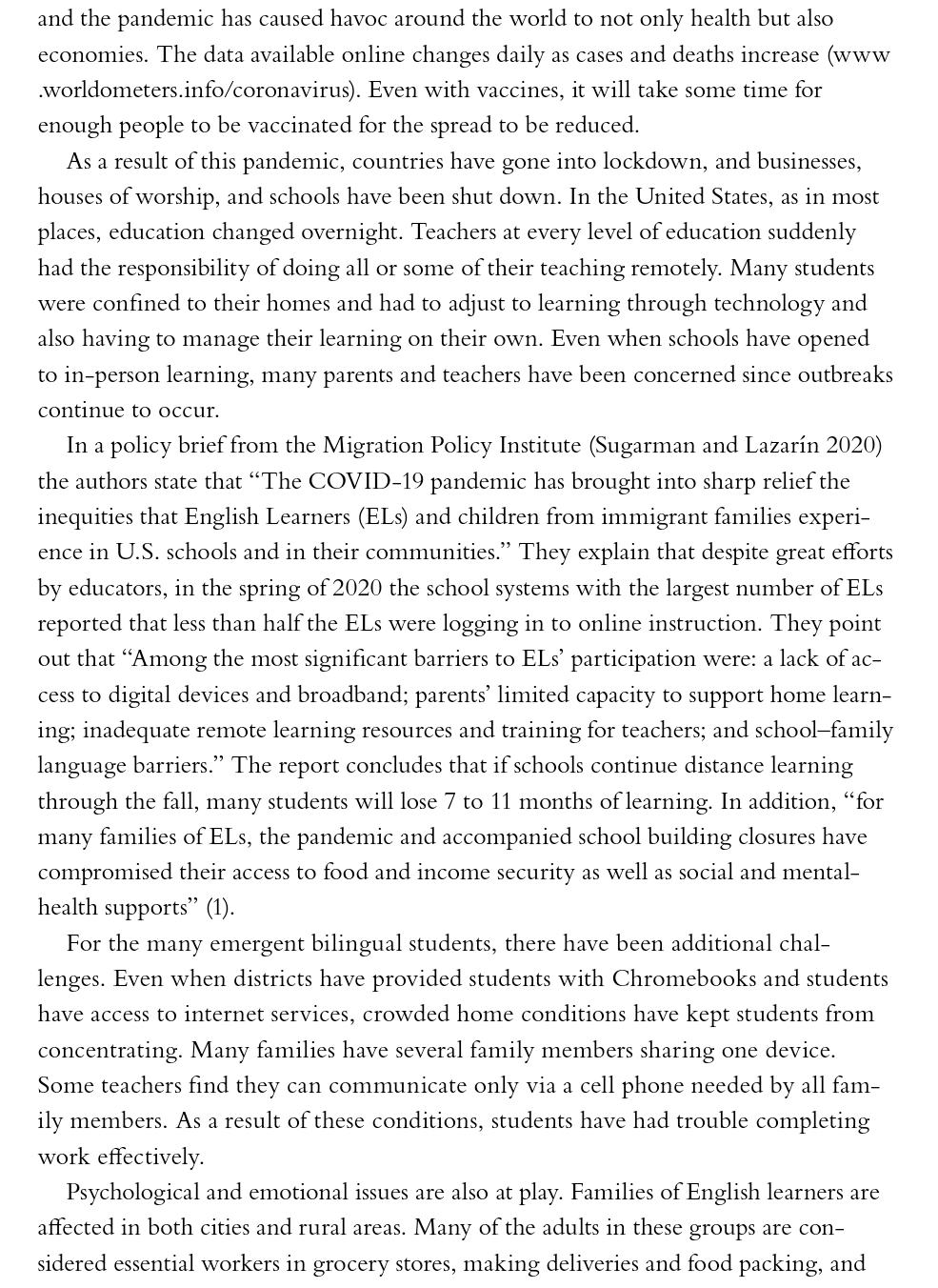

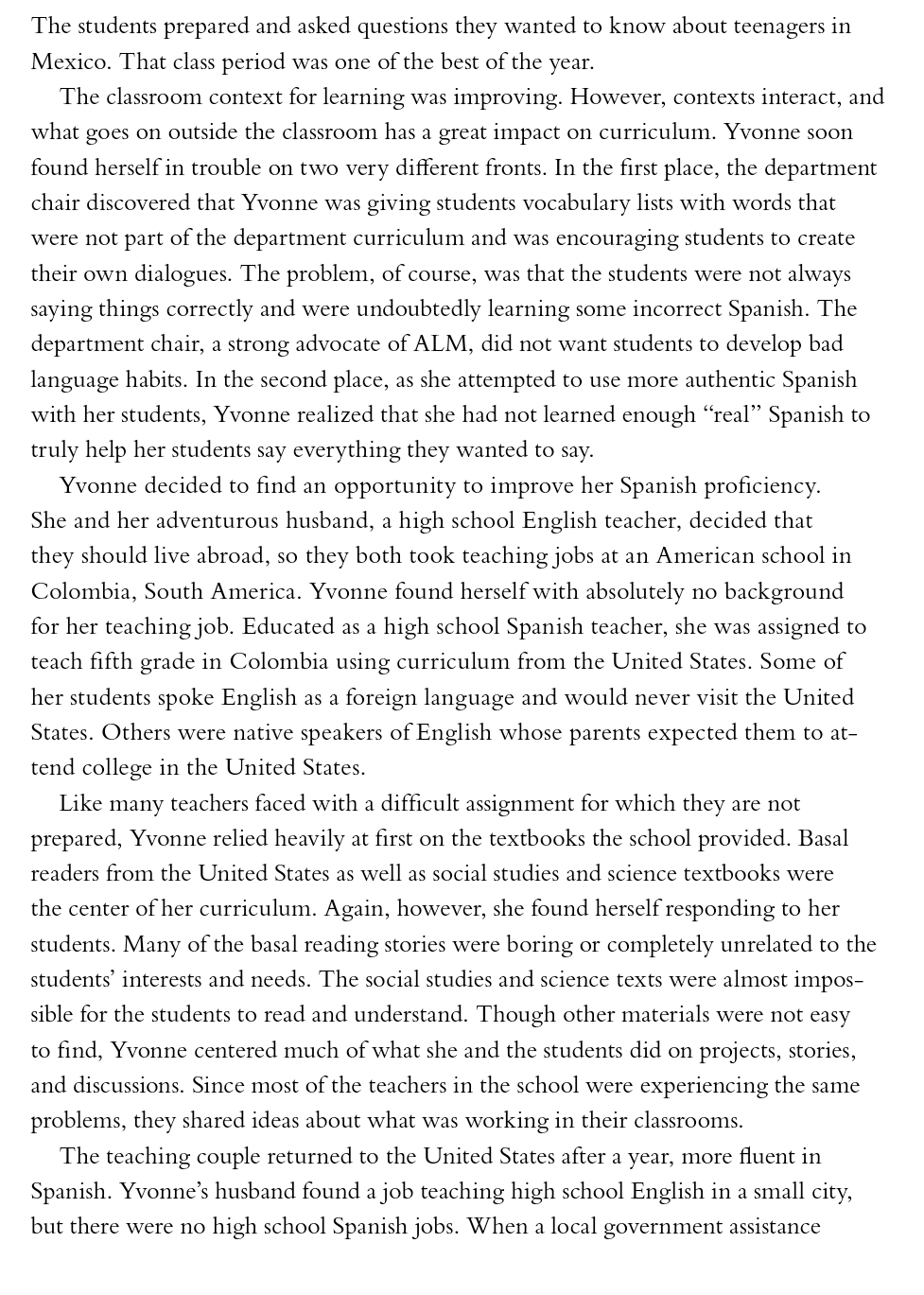

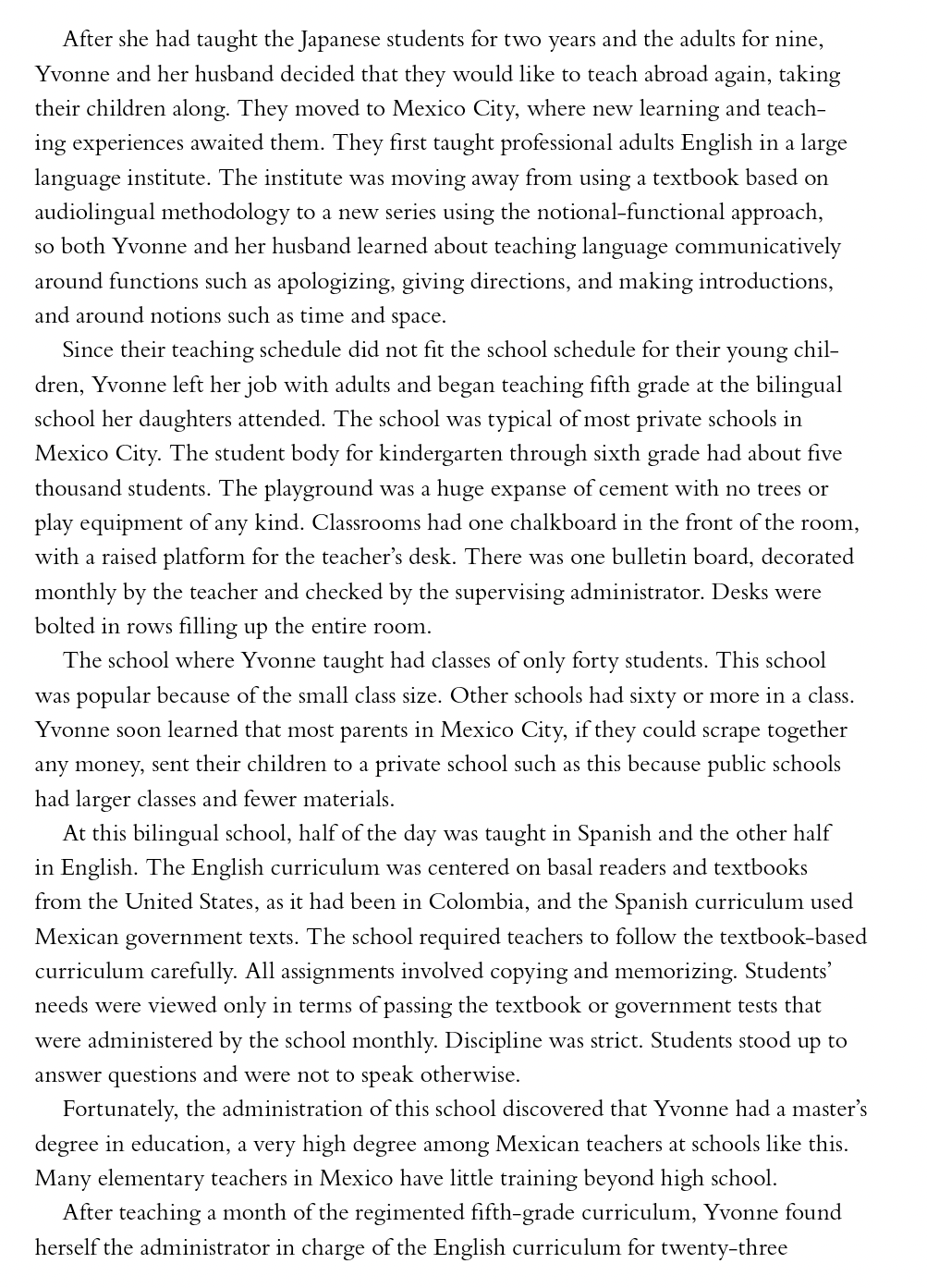

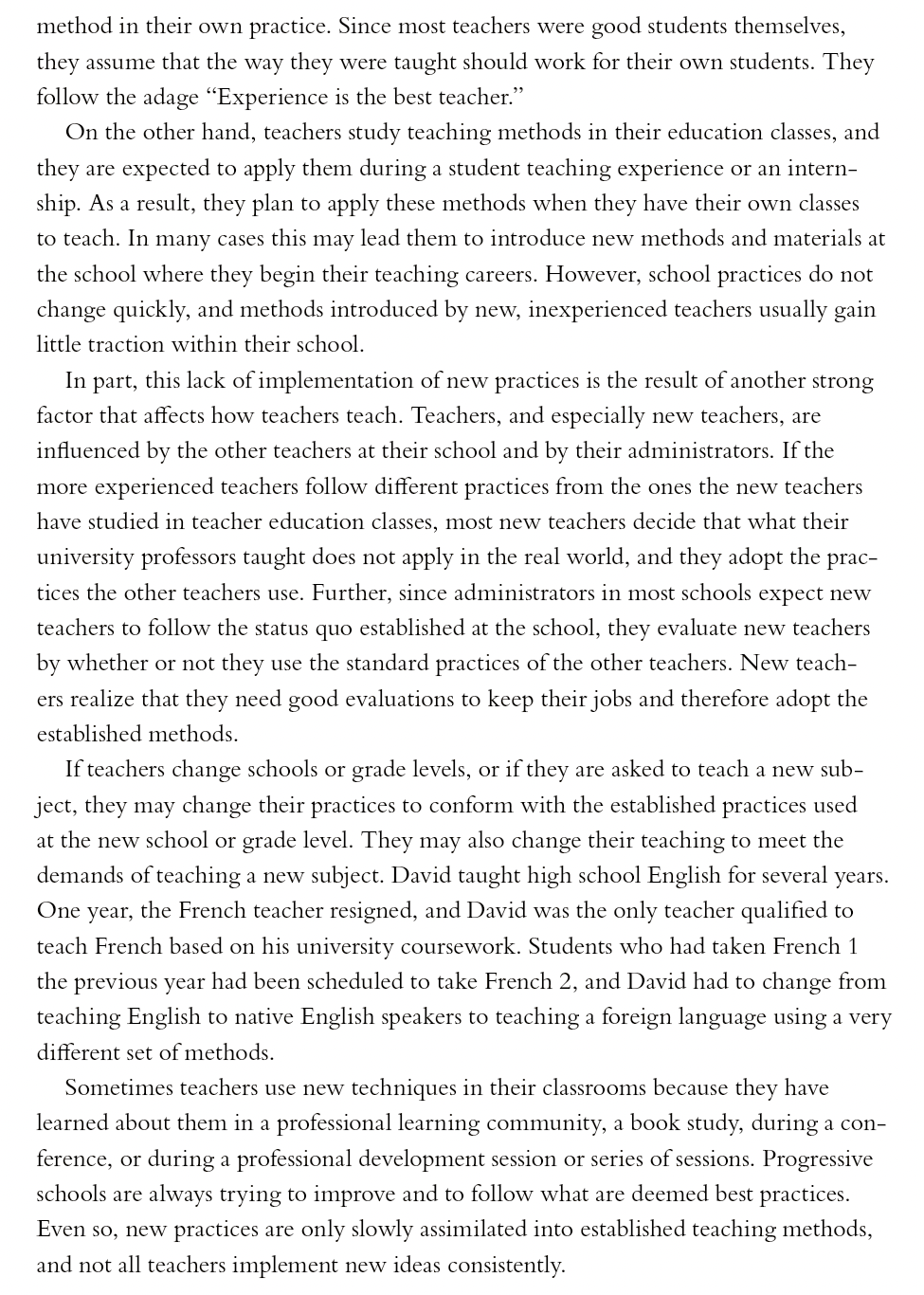

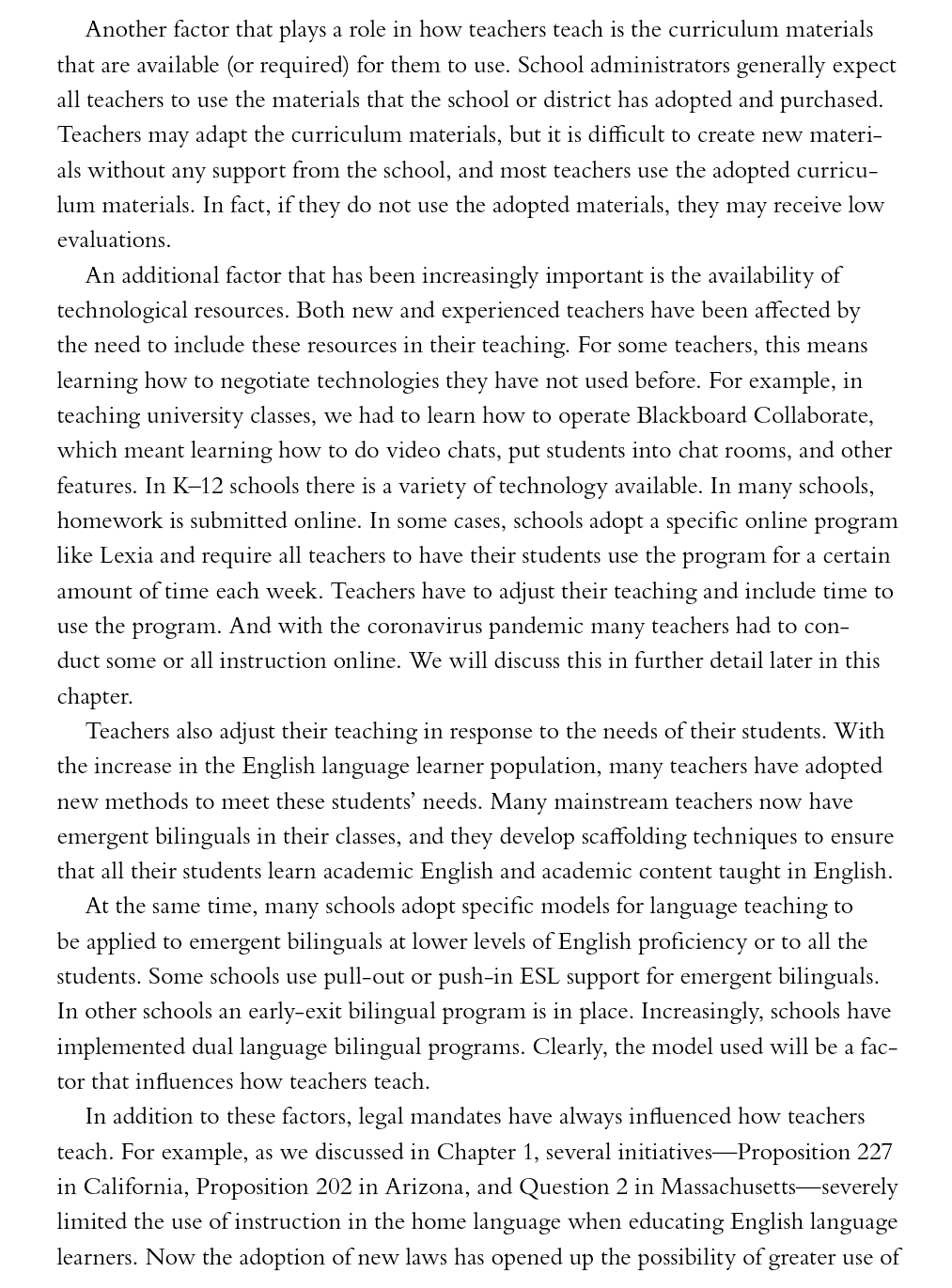

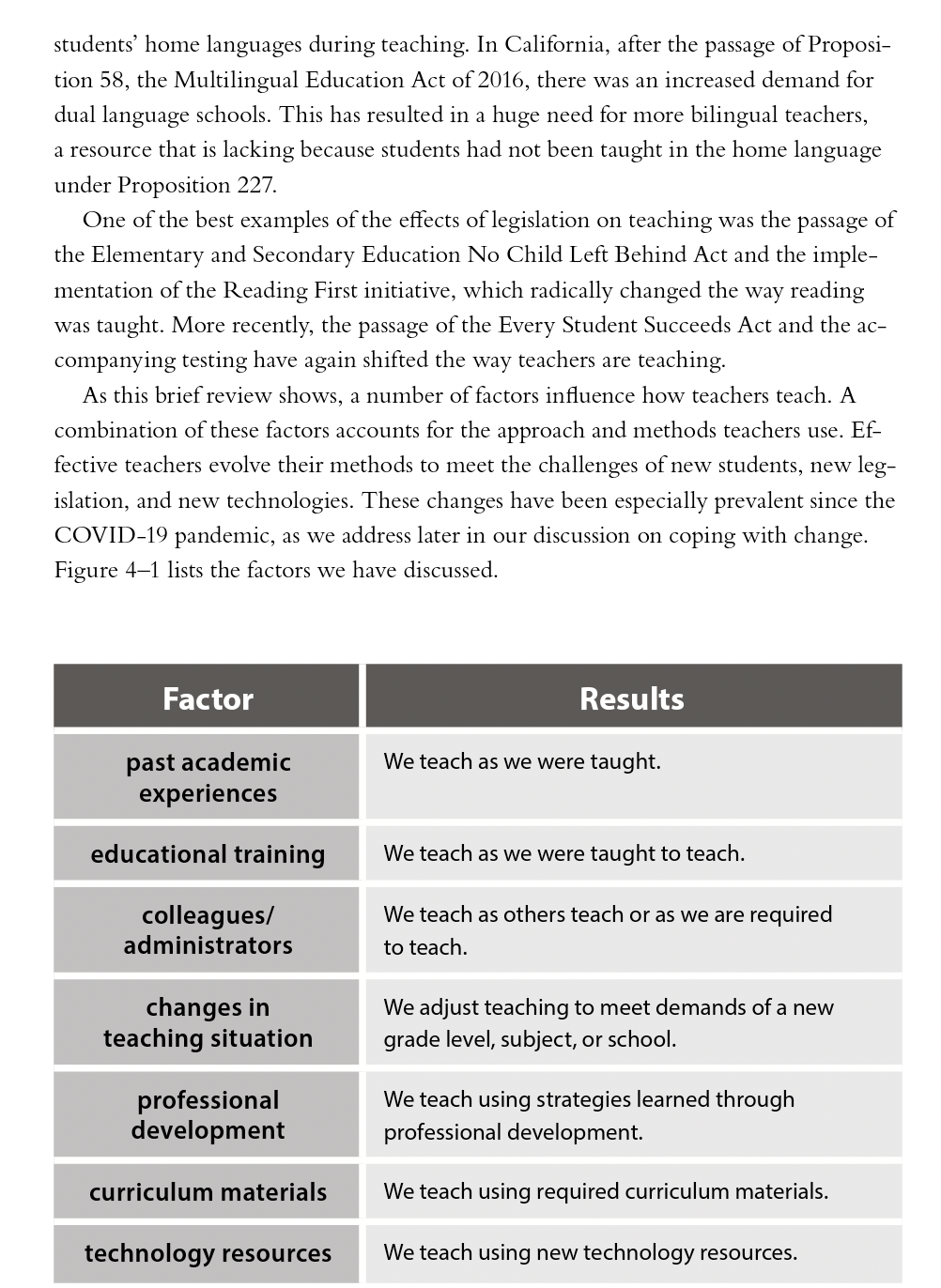

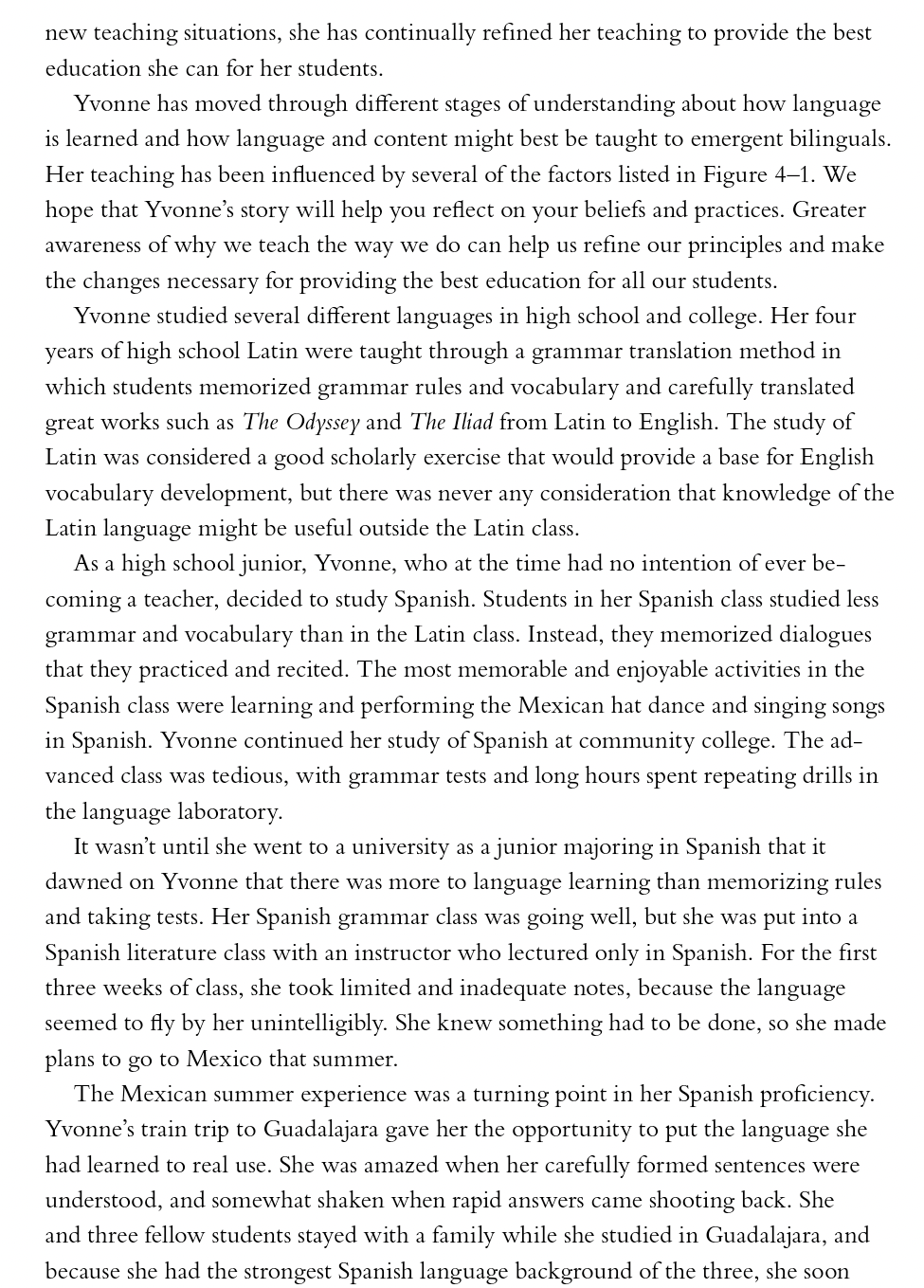

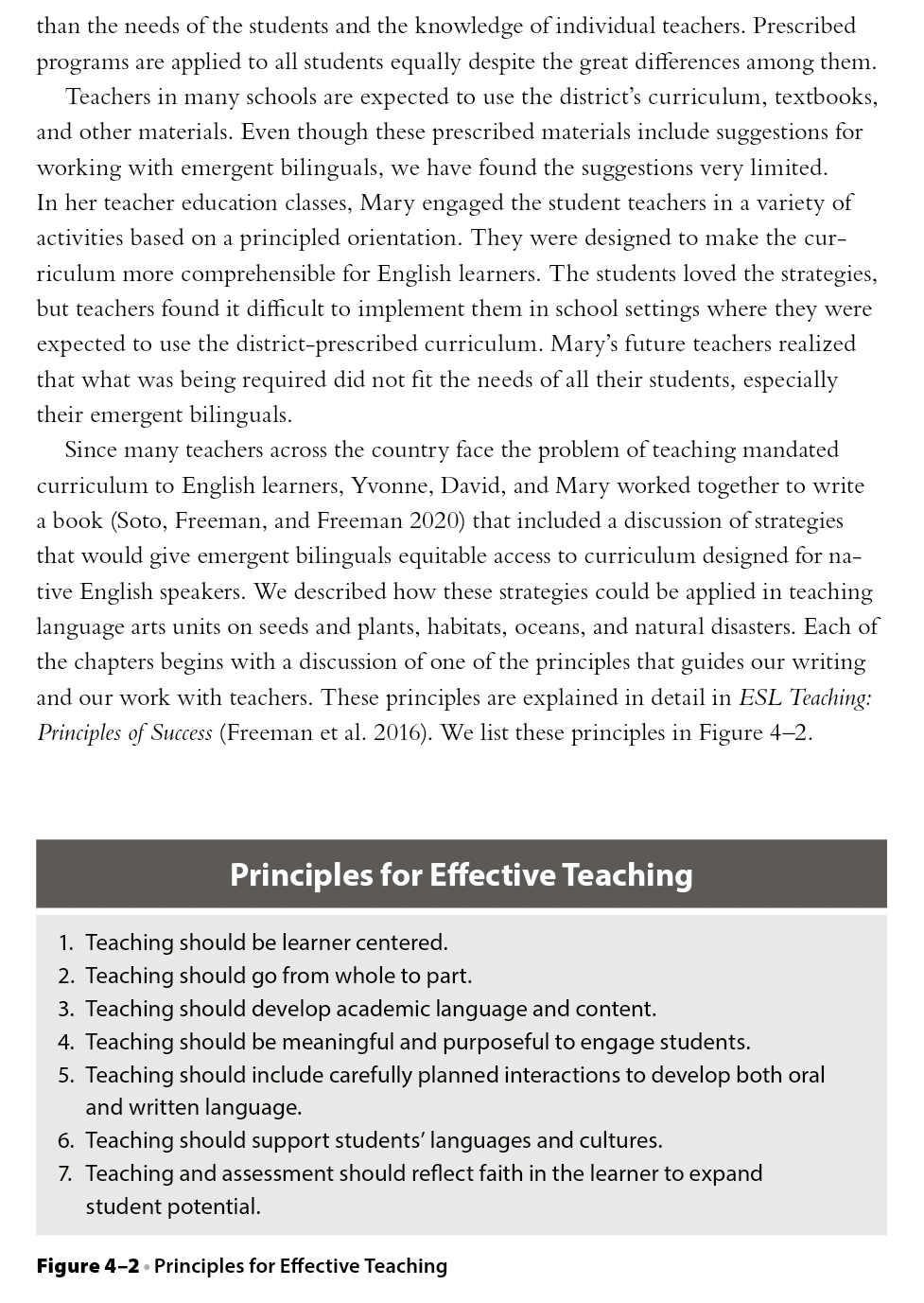

4 What Influences How Teachers Teach? Key Points Factors That Affect How Teachers Teach A variety of factors influence how teachers teach. Changes in legislative requirements such as the change from NCLB to ESSA have had a great impact on teachers of emergent bilinguals. Over time people's orientations toward English learners have changed, from viewing their home language as a handicap to seeing it as a civil right to more recently viewing it as a resource, and these shifts in orientation have resulted in different programs for teaching emergent bilinguals. Teachers' attitudes toward teaching emergent bilinguals have a strong influence on student success. Coping with the changes in student population and changes in legal requirements for teaching and testing is stressful for teachers. Coping with change during the COVID-19 pandemic will result in a new normal, and teaching online will become something that most teachers will need to adjust to in some form. When we visit classes, we see teachers using a variety of techniques and methods to help their students learn English and academic content. This variation is not surprising. In fact, even within the same school and at the same grade level with a similar student population, teachers differ consider- ably in how they teach. Why is this? In this chapter the basic question we wish to explore is, What influences how teachers teach? A number of factors seem to be at work, and these help to account for the variation in classroom practices we have observed. For one thing, teachers have been students themselves, and often the way they teach reflects the way that they were taught. If they were taught a second or foreign language using drills and dialogues based on the grammatical structure of the language, then they would naturally adopt a similar Yvonne's story shows how teachers can become principled by reflecting on their teaching and increasing their understanding of current research and theory. a method in their own practice. Since most teachers were good students themselves, they assume that the way they were taught should work for their own students. They follow the adage Experience is the best teacher. On the other hand, teachers study teaching methods in their education classes, and they are expected to apply them during a student teaching experience or an intern- ship. As a result, they plan to apply these methods when they have their own classes to teach. In many cases this may lead them to introduce new methods and materials at the school where they begin their teaching careers. However, school practices do not change quickly, and methods introduced by new, inexperienced teachers usually gain little traction within their school. In part, this lack of implementation of new practices is the result of another strong factor that affects how teachers teach. Teachers, and especially new teachers, are influenced by the other teachers at their school and by their administrators. If the more experienced teachers follow different practices from the ones the new teachers have studied in teacher education classes, most new teachers decide that what their university professors taught does not apply in the real world, and they adopt the prac- tices the other teachers use. Further, since administrators in most schools expect new teachers to follow the status quo established at the school, they evaluate new teachers by whether or not they use the standard practices of the other teachers. New teach- ers realize that they need good evaluations to keep their jobs and therefore adopt the established methods. If teachers change schools or grade levels, or if they are asked to teach a new sub- ject, they may change their practices to conform with the established practices used at the new school or grade level. They may also change their teaching to meet the demands of teaching a new subject. David taught high school English for several years. One year, the French teacher resigned, and David was the only teacher qualified to teach French based on his university coursework. Students who had taken French 1 the previous year had been scheduled to take French 2, and David had to change from teaching English to native English speakers to teaching a foreign language using a very different set of methods. Sometimes teachers use new techniques in their classrooms because they have learned about them in a professional learning community, a book study, during a con- ference, or during a professional development session or series of sessions. Progressive schools are always trying to improve and to follow what are deemed best practices. Even so, new practices are only slowly assimilated into established teaching methods, and not all teachers implement new ideas consistently. Another factor that plays a role in how teachers teach is the curriculum materials that are available (or required) for them to use. School administrators generally expect all teachers to use the materials that the school or district has adopted and purchased. Teachers may adapt the curriculum materials, but it is difficult to create new materi- als without any support from the school, and most teachers use the adopted curricu- lum materials. In fact, if they do not use the adopted materials, they may receive low evaluations. An additional factor that has been increasingly important is the availability of technological resources. Both new and experienced teachers have been affected by the need to include these resources in their teaching. For some teachers, this means learning how to negotiate technologies they have not used before. For example, in teaching university classes, we had to learn how to operate Blackboard Collaborate, which meant learning how to do video chats, put students into chat rooms, and other features. In K12 schools there is a variety of technology available. In many schools, homework is submitted online. In some cases, schools adopt a specific online program like Lexia and require all teachers to have their students use the program for a certain amount of time each week. Teachers have to adjust their teaching and include time to use the program. And with the coronavirus pandemic many teachers had to con- duct some or all instruction online. We will discuss this in further detail later in this chapter. Teachers also adjust their teaching in response to the needs of their students. With the increase in the English language learner population, many teachers have adopted new methods to meet these students' needs. Many mainstream teachers now have emergent bilinguals in their classes, and they develop scaffolding techniques to ensure that all their students learn academic English and academic content taught in English. At the same time, many schools adopt specific models for language teaching to be applied to emergent bilinguals at lower levels of English proficiency or to all the students. Some schools use pull-out or push-in ESL support for emergent bilinguals. In other schools an early-exit bilingual program is in place. Increasingly, schools have implemented dual language bilingual programs. Clearly, the model used will be a fac- tor that influences how teachers teach. In addition to these factors, legal mandates have always influenced how teachers teach. For example, as we discussed in Chapter 1, several initiativesProposition 227 in California, Proposition 202 in Arizona, and Question 2 in Massachusettsseverely limited the use of instruction in the home language when educating English language learners. Now the adoption of new laws has opened up the possibility of greater use of students' home languages during teaching. In California, after the passage of Proposi- tion 58, the Multilingual Education Act of 2016, there was an increased demand for dual language schools. This has resulted in a huge need for more bilingual teachers, a resource that is lacking because students had not been taught in the home language under Proposition 227. One of the best examples of the effects of legislation on teaching was the passage of the Elementary and Secondary Education No Child Left Behind Act and the imple- mentation of the Reading First initiative, which radically changed the way reading was taught. More recently, the passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act and the ac- companying testing have again shifted the way teachers are teaching. As this brief review shows, a number of factors influence how teachers teach. A combination of these factors accounts for the approach and methods teachers use. Ef- fective teachers evolve their methods to meet the challenges of new students, new leg- islation, and new technologies. These changes have been especially prevalent since the COVID-19 pandemic, as we address later in our discussion on coping with change. Figure 41 lists the factors we have discussed. Factor Results We teach as we were taught. past academic experiences educational training We teach as we were taught to teach. colleagues/ administrators We teach as others teach or as we are required to teach. changes in teaching situation We adjust teaching to meet demands of a new grade level, subject, or school. professional development We teach using strategies learned through professional development. curriculum materials We teach using required curriculum materials. technology resources We teach using new technology resources. Factor Results students We teach in response to our students' needs. legislation We teach to ensure that students meet the requirements. Figure 4-1. Factors That Influence How Teachers Teach Orientations Toward Language Legal mandates, such as the shift from NCLB to ESSA that we described earlier, reflect the ways people view effective educational practices. These changing views strongly affect how teachers teach, especially the way they teach emergent bilinguals. The programs and materials that are developed reflect current views. The shifting atti- tudes toward speakers of non-English languages are reflected in the kinds of programs for English language learners that have been offered in US schools during the last half of the twentieth century and now in the twenty-first century. Ruz (1984) has described these changes by tracing the historical development of three different orientations toward students' home languages: language as a handicap, language as a right, and language as a resource. He defines an orientation as a com- plex of dispositions toward language and its role, and toward languages and their role in society (16). During the fifties and sixties, language as a handicap was the prevalent orientation. Ruz points out that at this time, educators saw English language learners as having a problem, so that teaching English, even at the expense of the first language, became the objective of school programs (19). In other words, educators with this orientation believed that to overcome the handicap they had, English learners had to transition to English as quickly as possible. This orientation resulted in the establishment of ESL and transitional bilingual programs. These programs were designed to compensate for the language handicap these students were thought to have had. Ruz explains that in the seventies, the language-as-a-right orientation emerged. As a part of the civil rights movement, bilingual educators called for the rights of nonnative English speakers (NNES) to bilingual education. In many districts instruc- tion given in English excluded some students from access to a meaningful education. This began to change in 1974 when Chinese parents in San Francisco sued the school district for violation of the civil rights of their children. The school district claimed that the Chinese students were given an equal educa- tion because they were provided the same materials and taught the same content as native English speakers. The Chinese parents argued that by teaching non-English speakers in English, a language they did not understand, the district was denying them an equal opportunity to learn and discriminating against them under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Supreme Court sided with the parents in the Lau v. Nichols case. Although it did not require a specific program for English learners, the Supreme Court did is- sue guidelines for districts to follow. These guidelines called for schools to identify students with limited English proficiency and to provide special services that would give them access to the core curriculum. According to the Lau decision, schools could meet these requirements in different ways, including providing bilingual instruction or ESL. Students could be given some instruction in their home language or be placed in ESL classes. ESL teachers could pull out groups of students or work with main- stream teachers by providing extra support in the classes. In 1981 a second civil rights case provided clearer guidelines for the kinds of pro- grams that schools are required to implement in educating emergent bilinguals. In the case of Castaeda v. Pickard, the Fifth Circuit Court ruled that a school district in Texas had not provided an appropriate program for their English learners. Because of their low proficiency in English, the students could not participate equally in the school's instructional program. This case was important because the court established three criteria for any pro- gram serving English learners. The program must (1) be based on a sound educational theory, (2) be implemented effectively with adequate resources and personnel, and (3) after a trial period, be evaluated as effective in overcoming "language handicaps. Although the ruling still used the negative terminology of a language-as-a-handicap orientation, it established guidelines for programs for which English learners had a legal right. These three criteria have often been used by states and districts in evaluat- ing programs for English learners. Ruz (1984) also identifies a third orientation: language as a resource. He sees this orientation as a better approach to language planning for several reasons: It can have a direct impact on enhancing the language status of subordinate languages; it can help to ease tensions between majority and minority communities; it can serve as a more consistent way of viewing the role of non-English languages in U.S. society; and it highlights the importance of cooperative language planning. (2526) Dual language bilingual programs are all based on the language-as-a-resource orientation. These programs have raised the status and importance of languages other than English in many communities across the United States. They raise the status of non-English languages, in part, because as native English-speaking children become bilingual, parents and students alike see the value of knowing more than one lan- guage. In some communities dual language programs have eased tensions between groups who speak different languages. The programs have helped build cross-cultural communities and cross-cultural friendships among students and parents, relationships that probably would not have developed without the programs. Dual language programs benefit both native speakers of English and native speak- ers of languages other than English (LOTE). These programs serve English language learners in a unique way because the English learners become proficient in English and, at the same time, develop and preserve their home language. Because their peers are also learning their language, they maintain pride in their home language and cul- ture. Native English speakers add proficiency in an additional language and increase their cross-cultural understanding. These benefits are the direct result of viewing all languages as valuable community resources. Another important trend in working with emergent bilinguals is the use of trans- languaging in ESL, bilingual, and dual language classrooms. Although we will discuss translanguaging in detail in Chapter 5, it is important to point out that when teachers use well-planned translanguaging strategies, they are drawing on their students' rich linguistic repertoires, which include home-language knowledge. They are using the linguistic repertoire as a resource. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK Think about your own teaching. What factors have influenced your methods? How has your teaching changed over time? Share your reflections. Consider your own orientations toward students' home languages. Have you seen their home languages as a handicap, right, or resource? Teacher Attitudes All the factors listed in Figure 41 may influence how a teacher teaches. In addition, teachers are also influenced by specific experiences they have. Loretta, a Mexican American who was teaching high school classes when we worked with her, reflected on her student teaching experience: During my student teaching experience, I had the opportunity to work with ESL classes in math, history, and English. In one of these classes the teacher was trying to give me some of her educational insight. She told me that the Asian students (Lao, Hmong, etc.) were much better students than the Mexican students. She went on to say that these [Asian] children wanted to learn and were not a behavioral problem like the others. I do not think she knew that I was Mexican. Needless to say, I was extremely bothered by her remarks, and I immediately went home and shared this experience with my parents. They were both angered by her false statements. They felt that this new wave of immigrants is being treated much better than they were when they were in school. The teacher Loretta worked with during her student teaching reflected an attitude that teachers working in schools with large numbers of immigrant students sometimes develop. As we mentioned earlier, teachers' opinions about students have an important influence on how they teach. We believe that some teachers may need to develop new attitudes toward the new students in their schools (Freeman and Freeman 1990). Based on their research in a number of schools, Surez-Orozco and Marks state, In schools that serve immigrant students we commonly find cultures of low teacher expectations; what is sought and valued by teachers is student compliance rather than curiosity or cognitive engagement (2016, 116). They found that the teacher expecta- tions were often based on teachers' stereotypical impressions of groups of students. This was the case for the teacher that Loretta worked with. Low expectations gener- ally result in teachers holding students to less challenging standards when what the students need is to be both challenged and supported. Almost every state now has a significant number of emergent bilinguals in schools at every grade level. Working with these students is both challenging and rewarding. Teachers have responded to changes in the school population in different ways. We have seen four common responses from teachers in schools with high populations of English learners. In describing these responses we will use hypothetical situations that represent what we have observed. In each scenario, teacher attitudes and perceptions, developed in response to the influences listed in Figure 41, play an important role in how teachers teach. We briefly analyze each scenario and then offer some possible positive responses. The scenarios we describe represent only a small proportion of the teachers we have worked with. The vast majority of teachers adjust to working with new student populations and report that they enjoy working with them. "Teaching Isn't Like It Used to Be" Mrs. Brown has taught kindergarten at Baker School in the south end of town for fifteen years. When she first began teaching there, the neighborhood was made up mostly of middle-class whites, but over the years large numbers of Blacks, Latinx, and Southeast Asians have moved into the area, causing a "white flight to the north. The majority of her present students arrive with limited English proficiency. Mrs. Brown complains that these new students cannot do what her students in the past could. She remembers the past fondly. On the first day of school, children arrived eager to learn, holding the hands of parents who offered support. Now, she complains, the students, especially the Southeast Asian children, enter the classroom reluctantly. They are either alone or with parents who don't speak English and seem eager to escape as quickly as possible. Though she has an English-only rule for the classroom, she constantly has to remind students not to speak their native languages. Her biggest complaints are that the children don't seem motivated and the parents don't care. ANALYSIS There are several reasons that Mrs. Brown may be responding as she is. In the earlier days, most of her students spoke English and came from a background similar to hers. She now finds herself trying to teach students who not only do not speak the same language literally but also do not understand her customs and values any more than she does theirs. Previously, Mrs. Brown had strong parent support, but now she is not sure how to communicate with the parents. Mrs. Brown does not know how to change her teaching to help students, and she responds by blaming them and their families. POSITIVE RESPONSES Many teachers who suddenly find themselves with large numbers of English lan- guage learners make it a point to inform themselves about their new students. They read and discuss books and articles about other teachers working with emergent bilinguals. They talk with their fellow teachers and share materials and ideas that have been successful. They attend workshops offered by school districts and local universities. They join professional organizations for teachers of bilingual and second language learners. Once they learn more about emergent bilinguals, they become advocates for them. They seek people and materials that can provide home-language support, and they promote school events that highlight different cultural traditions. In addition, they make an effort to include the parents of their new students, not only at special events but in the regular classroom day. Even if parents do not speak English, teachers invite them to class to read a book in their first language, cook, or do crafts. Though all of these things require extra effort, they make these teachers' classrooms exciting places where all their students learn. "English Learners Make Me Look Like a Failure" Ms. Franklin is a second-year, second-grade teacher. Like most nontenured teachers in the district, she has been assigned to a classroom of diverse students, mostly Latinx, but also including a Somali refugee, two students from Iraq, and one student from China. Many of her students are classified as LEP. Ms. Franklin's teacher education program included some coursework in second language acquisition, ESL methodol- ogy, and diversity. As soon as she began to work with her emergent bilinguals last year, she fell in love with them. She read with the children, encouraged them to write often, and, in general, created activities that drew on their interests and background knowledge. The children responded well to this type of program, and she could see tremendous growth in their English. Despite this success, Ms. Franklin has encountered problems. She teaches in a school that has not met the state goals for annual yearly progress. The test scores for her students have remained low, and the principal has talked about this with Ms. Franklin. Even though he did not threaten her directly, Ms. Franklin now feels her job is on the line. From the coursework she has taken and her own experiences, she realizes that standardized tests do not chart the progress of her bilingual students fairly. Still, she is tempted to try this year to teach to the test, despite the fact that she does not feel that worksheets and drills are meaningful to her students, espe- cially to her second language learners. She is beginning to view her students as hav- ing deficitsdeficits that could have direct consequences for her career. She is also beginning to wish that she could transfer to a school in another part of town with fewer English learners. ANALYSIS Ms. Franklin began her teaching with enthusiasm and caring. Her college coursework prepared her to work effectively with English learners. However, Ms. Franklin is a new teacher and not really experienced enough to defend her curriculum. The emphasis on test scores has begun to erode her confidence in doing what is best for her students. She is beginning to view the students she once was trying to help as the source of her problems. Her solution is to try to get away from her present teaching situation. POSITIVE RESPONSES Many of the teachers who take our graduate courses are like Ms. Franklin. They are new teachers who want to help their students and are studying second language acquisition. However, they are concerned because they feel pressure from standardized testing and do not want to be judged by the poor performance of emergent bilinguals. After taking further graduate coursework, these teachers begin to understand how long it takes to speak, read, and write a second language with near-native proficiency and how critical home-language support is for content learning. Even when teachers use effective practices, emergent bilinguals need about five years to meet state norms on standardized tests (Collier 1989; Cummins 1981; Hakuta, Butler, and Whitt 2000). It is important for administrators to understand this research. In addition, schools should use formative assessments (MacDonald et al. 2015) to monitor and document their emergent bilinguals' progress. If the emergent bilinguals can be shown to be making consistent progress, then state agencies should not penal- ize schools, and this is happening in many states. The key is for schools to adjust their programs to ensure that all their student popu ions are succeeding. In many districts schools have instituted dual language bilingual programs, since these programs have been shown to be the most effective programs for emergent bilinguals, and native English speakers also improve (Freeman, Freeman, and Mercuri 2018). "It's Not Fair to the Rest of My Class to Give Those Students Special Attention" Mr. Martin teaches in a farming community where he has lived since he was a child. At the beginning of the year, his sixth-grade class included a group of Latinx children who were all fairly proficient in English and all reasonably successful learners. At the end of the first month of school, the principal called Mr. Martin in to explain that five sixth-grade migrant children had just arrived from Mexico and that they would be placed in Mr. Martin's class. Mr. Martin wasn't sure what to do with these new students, whose English was extremely limited. The district paid him to take training to learn new techniques, but he resented the idea that he had to attend extra classes and learn new ways to teach, es- pecially when he had been successful for a number of years. Why should he be the one to change? If these students couldn't meet the expectations for his class, maybe they weren't ready for it. Nevertheless, the students were in his class, and the principal was not about to transfer them out. Since he was a good teacher, Mr. Martin knew he should be doing something for them, and he felt guilty that they just sat quietly in the back of his class- room. On the other hand, it seemed to him that giving those students special attention wasn't fair to the rest of the students, who were doing just fine with his traditional in- struction. At the same time, the extra training he was receiving made him feel guilty because it stressed that teachers should not simply give students busywork; they should engage students in meaningful activities with other students in the classroom. How- ever, Mr. Martin's teaching style did not include much student interaction. He became doubly frustrated, as he felt that he was being asked not only to deal with new students but also to change his way of teaching. ANALYSIS Mr. Martin, like Mrs. Brown, is a conscientious teacher in a school system that is changing. He has succeeded in the past and resents the fact that he has been desig- nated to deal with the new students. It is probable that the principal chose Mr. Martin because he was an experienced teacher, and she believed he could handle the new challenge. However, Mr. Martin feels singled out and resentful of the extra time and training necessary to work with emergent bilinguals. In addition, he believes that giving them special instruction is actually going to be detrimental to his other stu- dents. At this point, Mr. Martin does not understand that what is good instruction for emergent bilinguals is beneficial for all students. a POSITIVE RESPONSES Teachers we have worked with have come to realize that it is impossible to use a traditional teacher-centered model of teaching to reach a very diverse student body. In addition, as they try interactive activities in which heterogeneous groups of stu- dents work on projects together, they see that all their students, including their native English-speaking students, learn more. Several teachers who entered our graduate classes determined never to change their teaching styles later gave enthusiastic testimo- nials of how exciting teaching can be when it is organized around units of inquiry and includes literature studies, creative writing, and projects involving art, science, music, and drama. At the same time, it is important for schools to provide appropriate education for all their students. Placement for older students with limited formal schooling is difficult unless the school has developed specific programs to educate its students with limited formal education who also have low levels of English proficiency. More resources are now available to guide schools in working with this group of students, such as texts by Custodio and O'Loughlin (2017) and Samway, Pease-Alvarez, and Alvarez (2020); see also the CUNY-NYSIEB website (Carpenter, Espinet, and Pratt n.d.). a Who Wants to Be the Bilingual Teacher? Mr. Gonzlez went into bilingual education because he himself had come to the United States as a non-English-speaking child, and he knew how difficult it was to succeed in school as an emergent bilingual. His education classes had taught him that instruction in the home language helps children academically and actually speeds their success in English. He is a certified bilingual teacher. During his first two years of teaching, he enthusiastically worked with his fourth graders, supporting their home language and helping them succeed in their new language. By the end of the third year, when he was tenured, his enthusiasm began to wane. Mr. Gonzlez was troubled by the subtle way his fellow teachers treated him. The bilingual program was considered remedial, and constant remarks in the teachers' lounge showed him that fellow teachers did not really believe emergent bilinguals were capable of the kind of success other students could achieve. In addition, he had not been given good-quality materials for teaching in Spanish, and he had to spend extra time creating or finding resources. Further, the principal asked him to translate school documents going out to parents, and even for someone with high levels of pro- ficiency in a language, translation takes considerable time. In addition, Mr. Gonzlez soon discovered that Latinx children who were disci- pline problems were being transferred into his class throughout the year even though they were not English learners. When he objected, the principal explained that since he was Latinx, he could understand those children better. Mr. Gonzlez's attempts to explain that his program was geared to work with Spanish speakers to help them succeed academically, not th discipline problems, fell on deaf ears. He began to feel that his expertise was not respected and that his classroom was becoming a dumping ground. He put in a request to be taken out of the bilingual program. ANALYSIS Mr. Gonzlez's situation is one that has repeated itself many times in different school districts. When there is little understanding of what bilingual education really is and why it is important, bilingual teachers feel isolated and misunderstood. Often, unin- formed teachers make assumptions about emergent bilinguals and do not hesitate to express their opinions about the limited potential of that group of students. Some administrators who have heard about the importance of ethnic and cultural role models but do not really know the theory behind bilingual education try to find quick and easy solutions to problems of students from diverse backgrounds. In this case all Latinx were lumped together, and Mr. Gonzlez was asked to solve all the problems of the Latinx students at the school. Given these factors, it is no wonder that some bilingual teachers ask to be placed in nonbilingual classes. POSITIVE RESPONSES A bright spot in the area of bilingual education is the changing attitudes toward bilin- gual education and the continued increase in the number of dual language bilingual programs. These programs have had positive results for native English speakers and those learning English, as both groups become bilingual and biliterate. Nevertheless, dual language is difficult in contexts where not enough bilingual teachers are available, or where the emergent bilinguals speak multiple languages. For many languages there are not enough students speaking one language in a school to justify dual language programs. In schools that have a mix of emergent bilinguals with different home languages, teachers have experienced success using translanguaging when given instruction and guidance in using translanguaging effectively (Freeman, Soto, and Freeman 2016; Fu, Hadjioannou, and Zhou 2019; Garca, Ibarra Johnson, and Seltzer 2017; Garca and Kleyn 2016). a REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK Looking back at the scenarios of different teachers, which one(s) have you observed? Think of one or two specific examples of teachers whose attitudes affect their teaching, positively or negatively. Jot down some notes and share your example (without identifying the teacher). Coping with Changes in Student Populations Despite the positive changes that are taking place in some schools, there is still much to be done to improve the education of emergent bilinguals. Although many teach- ers and administrators are learning about English learners and are implementing effective programs in their schools, some schools have not adjusted to the changes in the school population. In their extensive study of immigrant youth in high schools, Surez-Orozco, Surez-Orozco, and Todorova (2008) found that only 10 percent of the students named a teacher as someone they would go to for help, 21 percent named a teacher as someone who respected them, and only 3 percent named a teacher as someone who was proud of them. When the researchers talked to the teachers and administrators about the students, they responded that they were happy to have new immigrants who had a desire to learn, [were] more disciplined, and value[d] education (Surez-Orozco, Surez- Orozco, and Todorova 2008, 134), but for long-term English learners there was less enthusiasm. In a teachers' lounge in a largely Dominican and Puerto Rican high school, the researchers heard a teacher ask her colleagues, who nodded as she spoke, "What do you expect me to do with these kids? Within the next few years, most of the girls will be pregnant and the boys are going to be in jail (Surez-Orozco, Surez-Orozco, and Todorova 2008, 137). In an interview with a superintendent of a highly diverse district with a large number of immigrants, the researchers asked, What is the hardest thing about your job?" He responded, To get the teachers to believe these children can learn (137). With the growing number of second lan- guage students, the process of developing the skills, knowledge, and positive attitudes for teaching the changing school population effectively becomes more critical daily. Change is stressful, but a number of teachers are not only coping with it but learning how to celebrate the growing diversity in their classrooms. Coping with Change During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic In 2019 in Wuhan, China, a novel coronavirus, COVID-19, spread rapidly. Unfortunately, it wasn't contained in China, and because of international travel, the virus spread throughout the world. By February 2021, there were almost 28 million cases reported in the US and more than 500 thousand deaths. The figures grow daily and the pandemic has caused havoc around the world to not only health but also economies. The data available online changes daily as cases and deaths increase (www .worldometers.info/coronavirus). Even with vaccines, it will take some time for enough people to be vaccinated for the spread to be reduced. As a result of this pandemic, countries have gone into lockdown, and businesses, houses of worship, and schools have been shut down. In the United States, as in most places, education changed overnight. Teachers at every level of education suddenly had the responsibility of doing all or some of their teaching remotely. Many students were confined to their homes and had to adjust to learning through technology and also having to manage their learning on their own. Even when schools have opened to in-person learning, many parents and teachers have been concerned since outbreaks continue to occur. In a policy brief from the Migration Policy Institute (Sugarman and Lazarn 2020) the authors state that The COVID-19 pandemic has brought into sharp relief the inequities that English Learners (ELs) and children from immigrant families experi- ence in U.S. schools and in their communities. They explain that despite great efforts by educators, in the spring of 2020 the school systems with the largest number of ELS reported that less than half the ELs were logging in to online instruction. They point out that Among the most significant barriers to ELs' participation were: a lack of ac- cess to digital devices and broadband; parents' limited capacity to support home learn- ing; inadequate remote learning resources and training for teachers; and school-family language barriers. The report concludes that if schools continue distance learning through the fall, many students will lose 7 to 11 months of learning. In addition, for many families of ELs, the pandemic and accompanied school building closures have compromised their access to food and income security as well as social and mental- health supports (1). For the many emergent bilingual students, there have been additional chal- lenges. Even when districts have provided students with Chromebooks and students have access to internet services, crowded home conditions have kept students from concentrating. Many families have several family members sharing one device. Some teachers find they can communicate only via a cell phone needed by all fam- ily members. As a result of these conditions, students have had trouble completing work effectively. Psychological and emotional issues are also at play. Families of English learners are affected in both cities and rural areas. Many of the adults in these groups are con- sidered essential workers in grocery stores, making deliveries and food packing, and as a result, they are exposed to the virus daily. Members of EL communities have above-average infection and death rates. Other immigrants have lost jobs because they worked in service industries that closed, like restaurants and hotels. Hunger has become an issue too, because children are no longer fed at school and parents some- times have no money for food to feed families. The stress on students and the families is immense. In all of this change, teachers have tried to use the resources they have to teach their students. Some teachers are more comfortable than others using online platforms that allow them to interact with students remotely, but all have noticed problems with students' attention spans and the stress students are experiencing. While many online resources have become available, the sudden inundation of possibilities is overwhelm- ing to many teachers trying to simply teach some key ideas each day. Students and teachers all want things to go back to normal. Schools have tried different ways to get students back into classrooms. That has meant creating smaller classes to provide physical distancing and having students wear masks. Some schools have had to remodel their ventilation systems. By making these changes, many schools have been able to offer a blend of teaching in person and online. All of these changes in settings where teachers had emergent bilingual students only made teaching more complex. Teachers ask themselves how they need to teach emergent bilinguals content using proven techniques and strategies in limited time frames. At this point, teachers are being creative and trying to find new ways to sup- port their English learners in person and remotely. Yvonne's Story A teacher's practice changes over time in response to new experiences and challenges, new studies, new materials, new types of students, new legal mandates, a new empha- sis on standards and accountability, and new environmental conditions. While teachers can learn from all their experiences, effective teachers develop a set of principles that guide their teaching. These principles are based on their understanding of research and theory in second language acquisition and second language teaching. They help teach- ers choose methods and techniques for working with their second language students. Yvonne's story provides a good example of a teacher who has developed principles that guide her teaching. As she has read theory and research and as she has experienced a new teaching situations, she has continually refined her teaching to provide the best education she can for her students. Yvonne has moved through different stages of understanding about how language is learned and how language and content might best be taught to emergent bilinguals. Her teaching has been influenced by several of the factors listed in Figure 41. We hope that Yvonne's story will help you reflect on your beliefs and practices. Greater awareness of why we teach the way we do can help us refine our principles and make the changes necessary for providing the best education for all our students. Yvonne studied several different languages in high school and college. Her four years of high school Latin were taught through a grammar translation method in which students memorized grammar rules and vocabulary and carefully translated great works such as The Odyssey and The Iliad from Latin to English. The study of Latin was considered a good scholarly exercise that would provide a base for English vocabulary development, but there was never any consideration that knowledge of the Latin language might be useful outside the Latin class. As a high school junior, Yvonne, who at the time had no intention of ever be- coming a teacher, decided to study Spanish. Students in her Spanish class studied less grammar and vocabulary than in the Latin class. Instead, they memorized dialogues that they practiced and recited. The most memorable and enjoyable activities in the Spanish class were learning and performing the Mexican hat dance and singing songs in Spanish. Yvonne continued her study of Spanish at community college. The ad- vanced class was tedious, with grammar tests and long hours spent repeating drills in the language laboratory. It wasn't until she went to a university as a junior majoring in Spanish that it dawned on Yvonne that there was more to language learning than memorizing rules and taking tests. Her Spanish grammar class was going well, but she was put into a Spanish literature class with an instructor who lectured only in Spanish. For the first three weeks of class, she took limited and inadequate notes, because the language seemed to fly by her unintelligibly. She knew something had to be done, so she made plans to go to Mexico that summer. The Mexican summer experience was a turning point in her Spanish proficiency. Yvonnes train trip to Guadalajara gave her the opportunity to put the language she had learned to real use. She was amazed when her carefully formed sentences were understood, and somewhat shaken when rapid answers came shooting back. She and three fellow students stayed with a family while she studied in Guadalajara, and because she had the strongest Spanish language background of the three, she soon found herself in the role of language negotiator. Her success with the family, a brief romantic interlude, and exciting weekend travel excursions convinced Yvonne that she had found her niche. Her interest in the Spanish language and the Latinx culture led naturally to her decision to become a Spanish teacher. Back in the United States, Yvonne enrolled in a cutting-edge teacher education program. In just one year, students in this program got both a teaching credential and a master's degree in education. Teacher training included videotaped micro teaching sessions that allowed student teachers to view their performance and critique their own lessons. Methodology classes presented the latest techniques of leading different kinds of audiolingual drills. These techniques were based on a behaviorist view of learning. In fact, one of her education-methods professors was considered an interna- tional expert on teaching language. Yvonne accepted the idea that learning, and espe- cially language learning, consisted of forming habits. All her own language instruction had assumed that kind of a model. In her classes, students had memorized dialogues, and teachers had corrected errors quickly. Yvonne and her classmates had repeated their lines as their cheerleading teachers led them rapidly through carefully selected language-pattern exercises. Yvonne's teacher education classes prepared her to teach as she had been taught. She received her credential and took a job in an inner-city high school. Despite all her preparation, her first teaching position was a real eye-opener. She was teach- ing five classes a day of Spanish 1. Her audiolingual method (ALM) Spanish 1 book included lesson after lesson of dialogues and drills. Her students hated what they called the boring repetition and stupid dialogues. Yvonne was devastated. She wanted her students to love speaking Spanish as much as she did. She remembered her posi- tive experiences in Mexico but had forgotten how bored she had been when forced through similar drills. Faced with 150 resisting and restless high school students each day, Yvonne be- gan to look closely at the lines from the dialogues that the students were repeating. Instinctively, without really knowing what she was doing, she began to change the dialogues to make them more relevant. A mi no me gustan las albndigas (I don't like meatballs) became A mi no me gustan las hamburguesas con cebolla (I don't like hamburg- ers with onion), and she encouraged the students to expand the talk to include other things they did not like. She even gave them choice in the dialogues they practiced. Yvonne wanted her students to realize that Spanish is a language that real people use for real purposes. She invited some friends visiting from Mexico to her class. The students prepared and asked questions they wanted to know about teenagers in Mexico. That class period was one of the best of the year. The classroom context for learning was improving. However, contexts interact, and what goes on outside the classroom has a great impact on curriculum. Yvonne soon found herself in trouble on two very different fronts. In the first place, the department chair discovered that Yvonne was giving students vocabulary lists with words that were not part of the department curriculum and was encouraging students to create their own dialogues. The problem, of course, was that the students were not always saying things correctly and were undoubtedly learning some incorrect Spanish. The department chair, a strong advocate of ALM, did not want students to develop bad language habits. In the second place, as she attempted to use more authentic Spanish with her students, Yvonne realized that she had not learned enough real Spanish to truly help her students say everything they wanted to say. Yvonne decided to find an opportunity to improve her Spanish proficiency. She and her adventurous husband, a high school English teacher, decided that they should live abroad, so they both took teaching jobs at an American school in Colombia, South America. Yvonne found herself with absolutely no background for her teaching job. Educated as a high school Spanish teacher, she was assigned to teach fifth grade in Colombia using curriculum from the United States. Some of her students spoke English as a foreign language and would never visit the United States. Others were native speakers of English whose parents expected them to at- tend college in the United States. Like many teachers faced with a difficult assignment for which they are not prepared, Yvonne relied heavily at first on the textbooks the school provided. Basal readers from the United States as well as social studies and science textbooks were the center of her curriculum. Again, however, she found herself responding to her students. Many of the basal reading stories were boring or completely unrelated to the students' interests and needs. The social studies and science texts were almost impos- sible for the students to read and understand. Though other materials were not easy to find, Yvonne centered much of what she and the students did on projects, stories, and discussions. Since most of the teachers in the school were experiencing the same problems, they shared ideas about what was working in their classrooms. The teaching couple returned to the United States after a year, more fluent in Spanish. Yvonne's husband found a job teaching high school English in a small city, but there were no high school Spanish jobs. When a local government assistance agency in their new town called to ask if she would volunteer to teach English to Spanish-speaking adults, Yvonne decided to try it. Her first class of students included two Mexican women with no previous schooling and a college-educated couple from Bolivia. With no materials, not even paper or pencils, and diverse students, Yvonne, in desperation, asked the students what English they wanted and needed to learn. Start- ing with any materials she could get, including props, maps, pamphlets, and resource guides, Yvonne soon found herself teaching a class that had grown to forty adults on a variety of topics including nutrition, shopping, community services, childcare, and geography. Yvonne's class became a part of the public school's adult education program, and Yvonne began teaming with another teacher who also loved teaching adult ESL. The two collaborated daily, making up skits, writing songs, organizing around themes, and creating a community with students who came from Mexico, Central America, South America, Northern and Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Japan, Korea, and South- east Asia. Though Yvonne had come a long way from having students memorize dialogues and do drills, she was still uncomfortable about what she should be doing to teach language. She and her team teacher, a former high school English teacher, often would pull out traditional grammar sheets and do a part of their daily lesson with some of those exercises to be sure the students understood the structure of the language. When those lessons seemed to go nowhere, especially with adults who had had little previous schooling, the teachers dropped the grammar books in favor of books with stories and discussion questions. However, the readings were seldom related to student needs and experiences, so the two teachers kept returning to skits, songs, and projects created around relevant themes. Yvonne and her partner had an additional experience that stretched them in new directions and strengthened their conviction that language learning was more than memorizing grammatical rules and repeating pattern drills. The two were asked to teach as adjunct instructors in an intensive English program at the local university. A large group of Japanese college students had arrived, and although these students had extensive background in English grammar and vocabulary, they understood and spoke little English. Initially, the Japanese students resisted classroom activities that were not carefully organized around grammar exercises, but Yvonne and her partner worked hard to get the students to take the risk to speak English in class and in the community. Several of the Japanese students came to appreciate the emphasis on using English for real purposes and began to attend the adult ESL classes as well as the university classes. After she had taught the Japanese students for two years and the adults for nine, Yvonne and her husband decided that they would like to teach abroad again, taking their children along. They moved to Mexico City, where new learning and teach- ing experiences awaited them. They first taught professional adults English in a large language institute. The institute was moving away from using a textbook based on audiolingual methodology to a new series using the notional-functional approach, so both Yvonne and her husband learned about teaching language communicatively around functions such as apologizing, giving directions, and making introductions, and around notions such as time and space. Since their teaching schedule did not fit the school schedule for their young chil- dren, Yvonne left her job with adults and began teaching fifth grade at the bilingual school her daughters attended. The school was typical of most private schools in Mexico City. The student body for kindergarten through sixth grade had about five thousand students. The playground was a huge expanse of cement with no trees or play equipment of any kind. Classrooms had one chalkboard in the front of the room, with a raised platform for the teacher's desk. There was one bulletin board, decorated monthly by the teacher and checked by the supervising administrator. Desks were bolted in rows filling up the entire room. The school where Yvonne taught had classes of only forty students. This school was popular because of the small class size. Other schools had sixty or more in a class. Yvonne soon learned that most parents in Mexico City, if they could scrape together any money, sent their children to a private school such as this because public schools had larger classes and fewer materials. At this bilingual school, half of the day was taught in Spanish and the other half in English. The English curriculum was centered on basal readers and textbooks from the United States, as it had been in Colombia, and the Spanish curriculum used Mexican government texts. The school required teachers to follow the textbook-based curriculum carefully. All assignments involved copying and memorizing. Students' needs were viewed only in terms of passing the textbook or government tests that were administered by the school monthly. Discipline was strict. Students stood up to answer questions and were not to speak otherwise. Fortunately, the administration of this school discovered that Yvonne had a master's degree in education, a very high degree among Mexican teachers at schools like this. Many elementary teachers in Mexico have little training beyond high school. After teaching a month of the regimented fifth-grade curriculum, Yvonne found herself the administrator in charge of the English curriculum for twenty-three teachers. She began to reflect on how many times she had found herself in positions she was unprepared for and yet how similar her conclusions were each time. Again, she wondered how meaningful the curriculum was for the students. If the Mexican students were studying at a bilingual school so that they could learn to read, write, and speak English, were the US textbooks appropriate? Should they be reading in basal readers about blond, blue-eyed Americans going to an American birthday party or go- ing ice-skating in snowy weather? Would they really learn English when their teachers rarely allowed them to speak English, or any language, in class, and when the teachers rarely spoke to them in either English or Spanish? Yvonne encouraged the teachers to center their curriculum on themes of interest to children of various ages. She collected stories and information related to celebra- tions, science topics, and biographies of famous people that seemed to lend themselves to language use and content learning. She encouraged teachers to involve students in drama and music using English songs and plays. She helped teachers write plays for their students and tried to encourage conversation activities. However, all of this was done on a limited basis, as the school requirements were stringent, and any activities beyond preparing students for tests were considered frills. After two years of teaching in Mexico City, Yvonne and her husband moved back to the United States, where her husband began graduate study and she took a posi- tion teaching senior composition and freshman English at a private high school. The composition class was organized around a packet of materials that students were to fol- low carefully, completing assignments at their own pace with no class discussion. The freshman English class curriculum included short stories, a library unit, the play Romeo and Juliet, and study of a grammar book written in England. Again, Yvonne looked at her students, this time all native speakers of English, and wondered about teaching to their interests and needs. In this situation, unlike the Mexico and the high school Spanish experiences, the English department chairperson was flexible and sympathetic to deviations from the set curriculum. Before the year was over, Yvonne had students in the composition class meeting in groups, having whole-class discussions, writing joint compositions, and sharing their writing. She largely ignored the grammar book for the freshmen, had them write and edit their own compositions, and encouraged discussion of their reading. Before teaching Romeo and Juliet, Yvonne planned with another freshman English teacher to have their stu- dents view the movie West Side Story, which provided them with valuable background for the Shakespeare play. a However, Yvonne did not feel that her previous experiences were best utilized by teaching English to high school students, so the following year, she went back to graduate school and worked as a graduate teaching assistant in the Spanish department. Her graduate work included both a second master's degree, this time in English as a second language, and doctoral work in education. In her ESL program she studied SLA theory and second language teaching methods. Many of the writers advocated a communicative approach to teaching language. She was especially impressed by the work of Krashen (1982), who differentiated between acquisition and learning, a distinction that made sense to Yvonne because of her own language learning and teaching experiences. While her ESL classes were interesting, it was her doctoral studies that really chal- lenged Yvonne to think seriously about learning and teaching and the relationship between the two. She majored in language and literacy and minored in bilingual education. This combination seemed to fit her interests and her experiences. She began studying about language learning with a focus on the development of second language literacy. As she read the work of Ferreiro and Teberosky (1982), Goodman (1986), Goodman et al. (1987), Halliday (1975), Halliday and Hasan (1989), Graves (1983), Heath (1983), Lindfors (1987), Piaget (1955), Smith (1988), and Vygotsky (1962, 1978), Yvonne began to make connect