Question: Please read the questions Question: Please explain in your own words, what transformative pedagogy is. Also, describe the ways in which you can include students'

Please read the questions

Question: Please explain in your own words, what transformative pedagogy is. Also, describe the ways in which you can include students' cultures and languages in a lesson plan . How will you make sure that your plan is equitable to all students

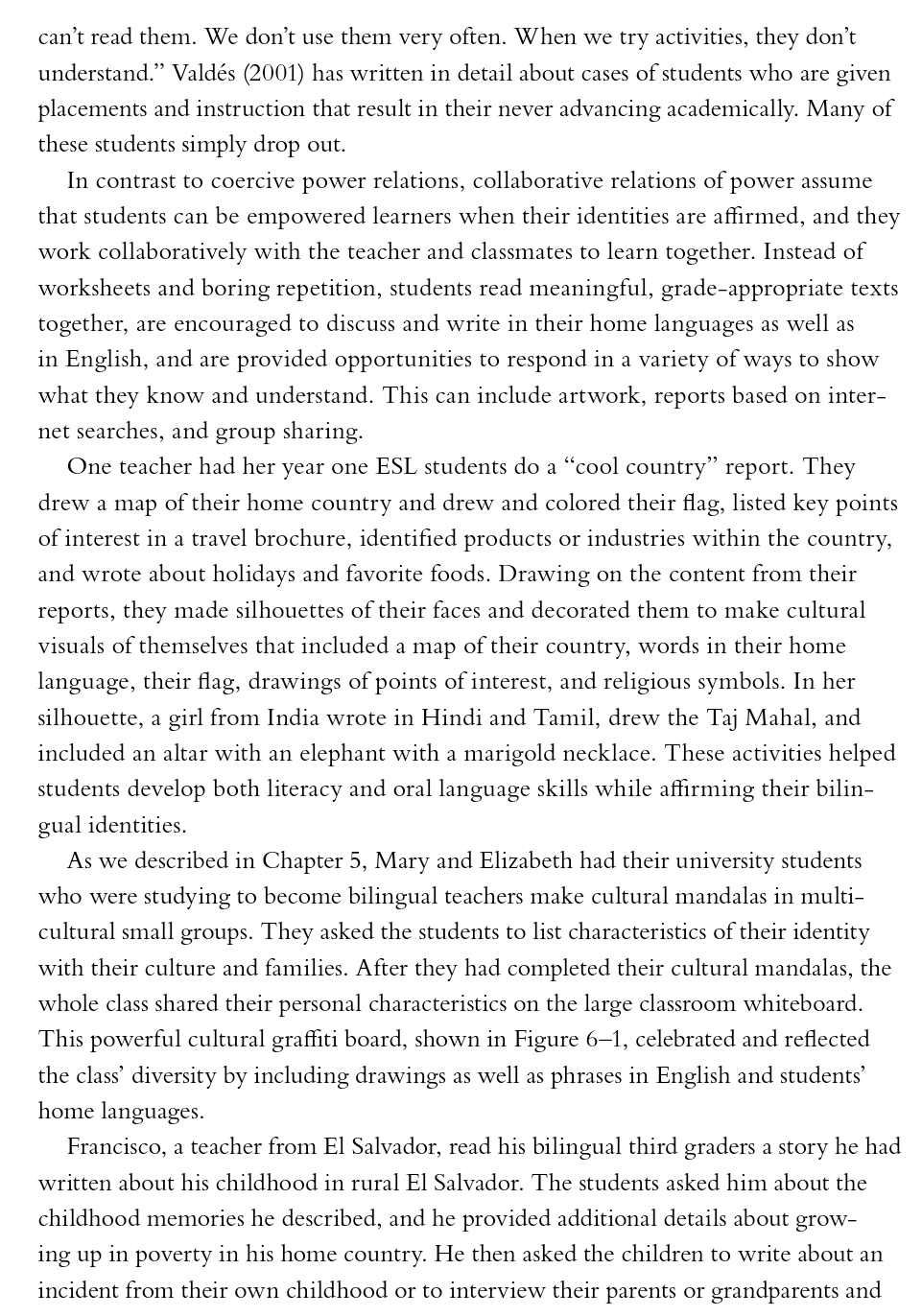

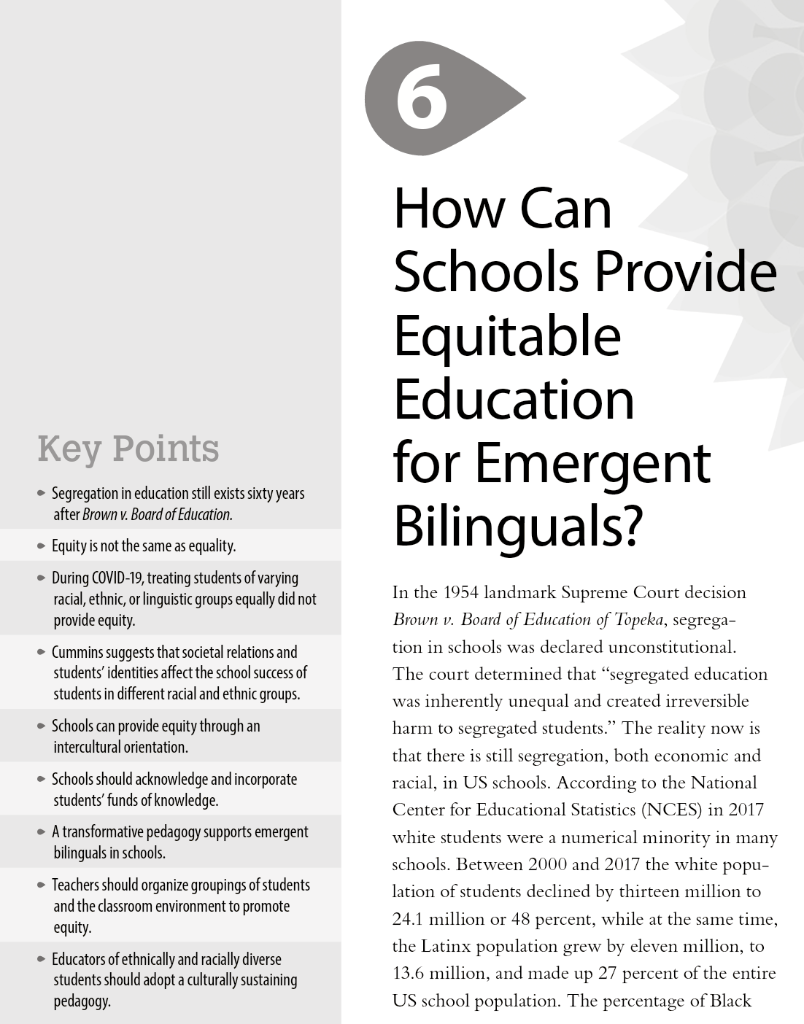

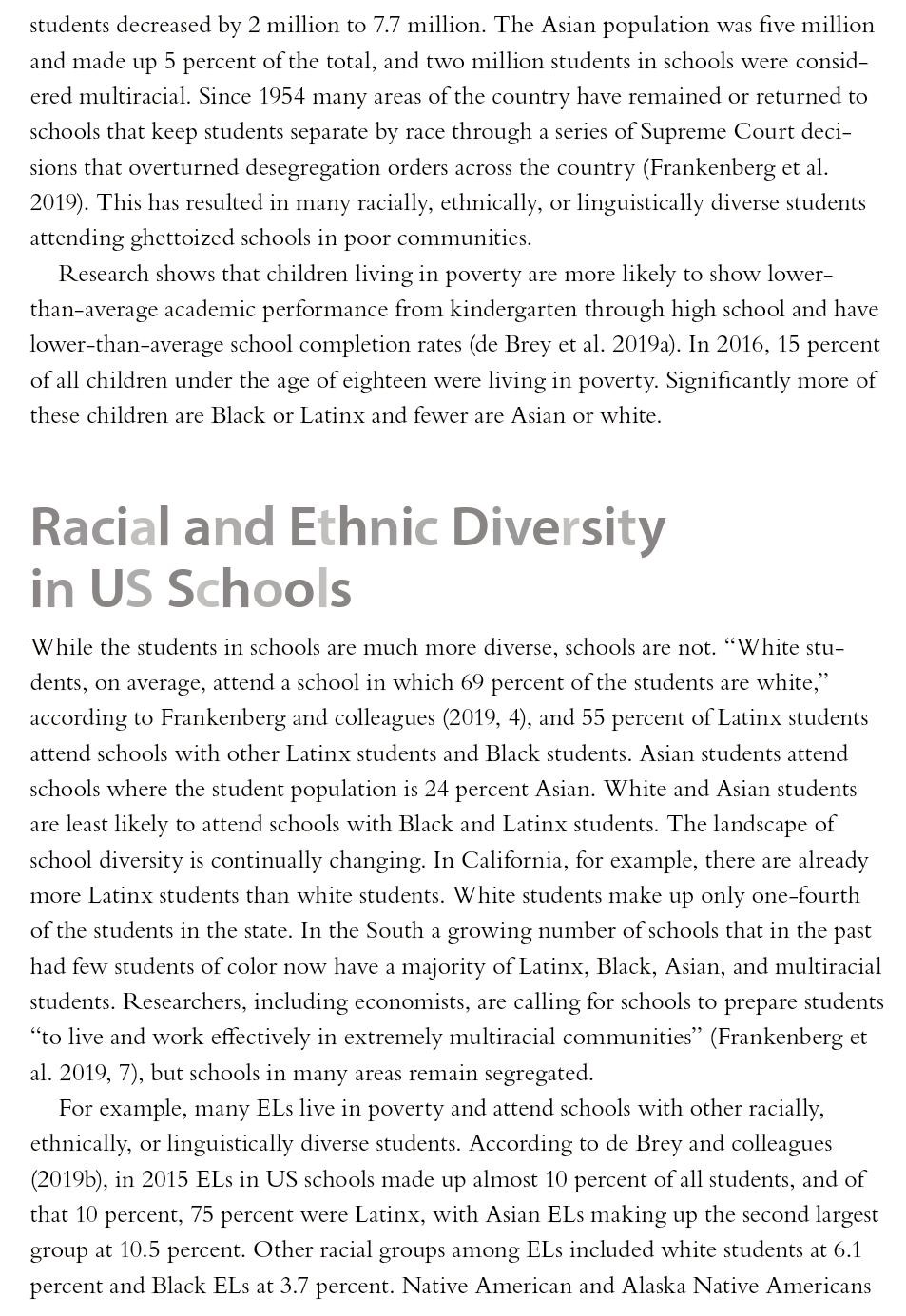

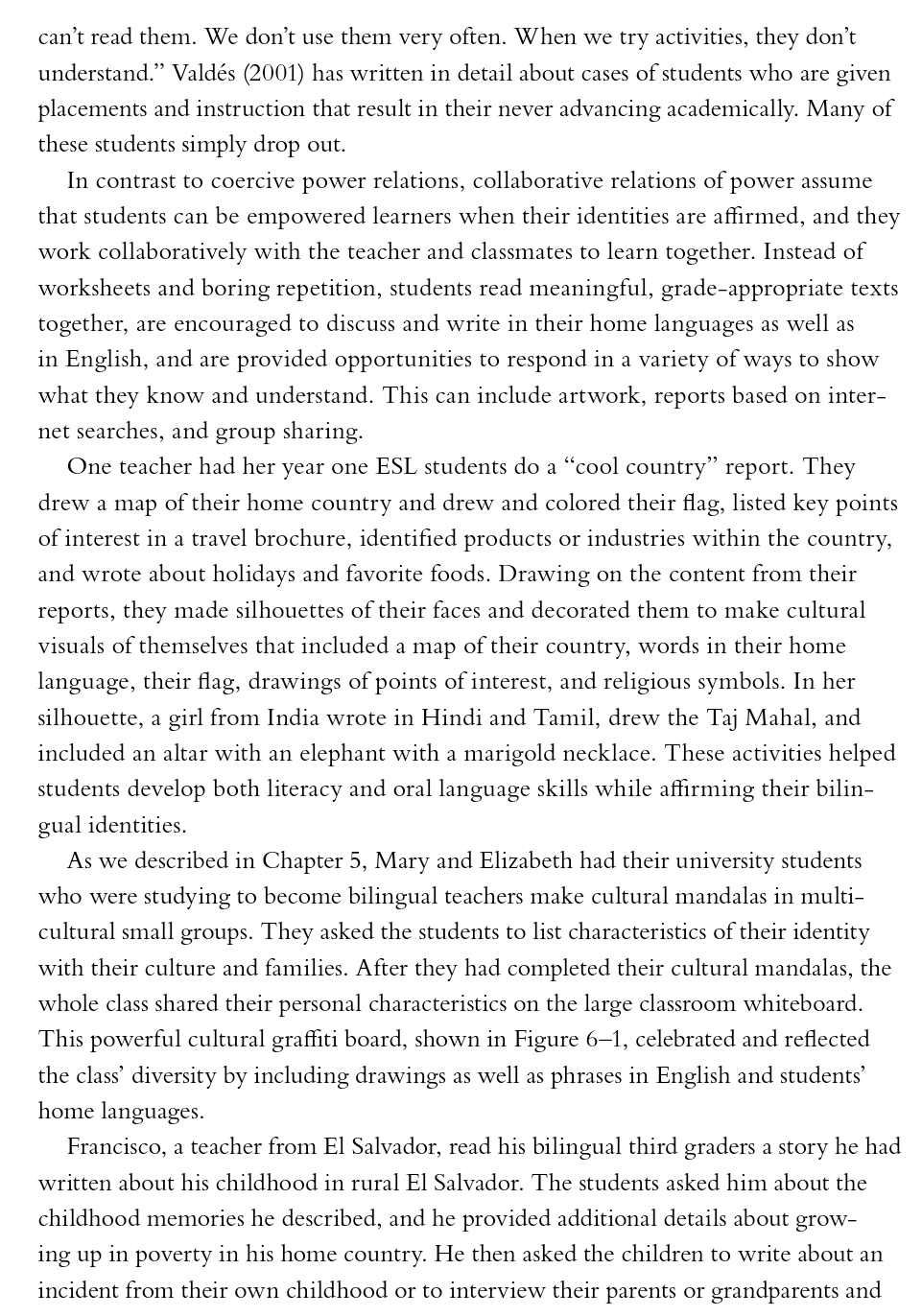

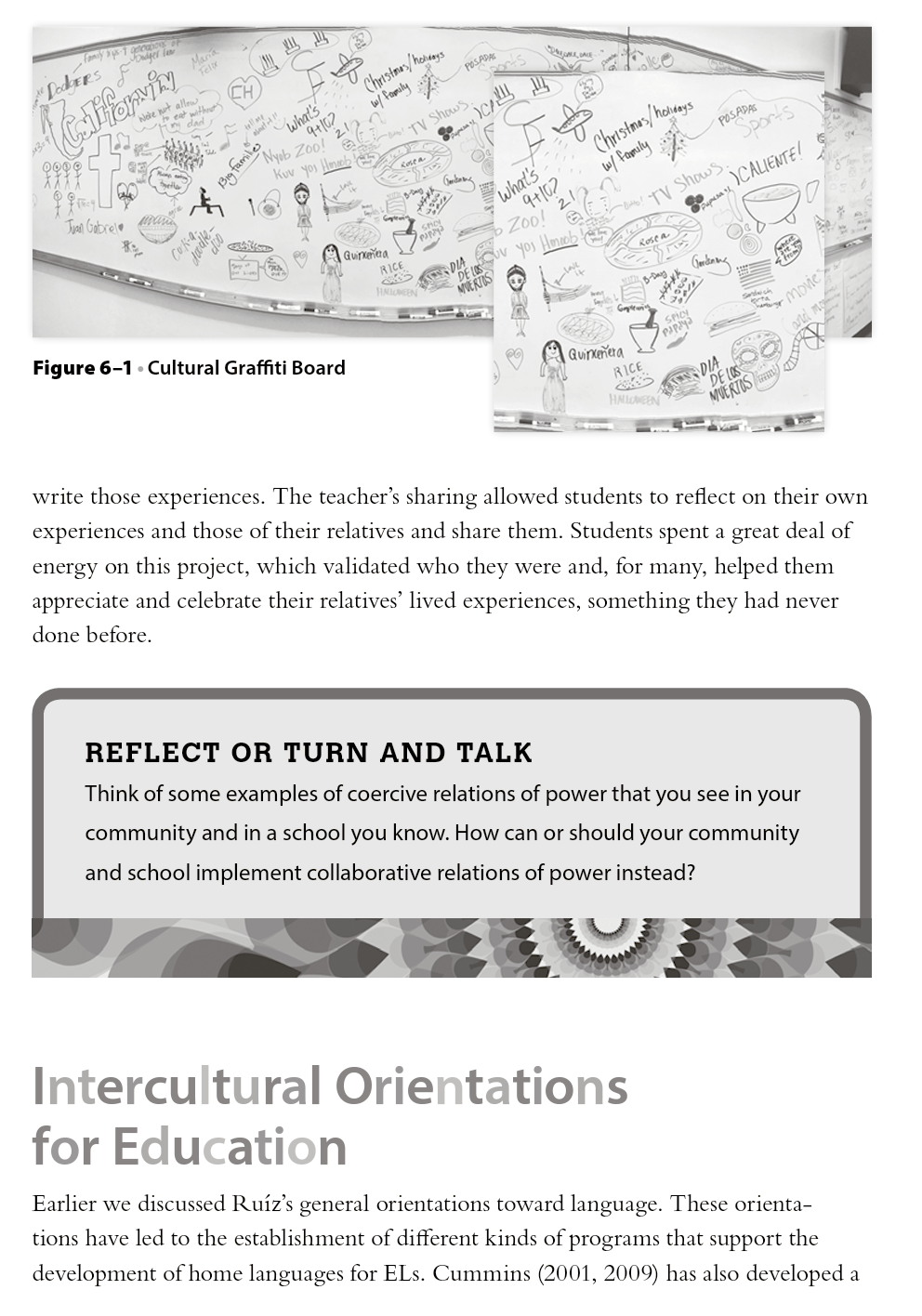

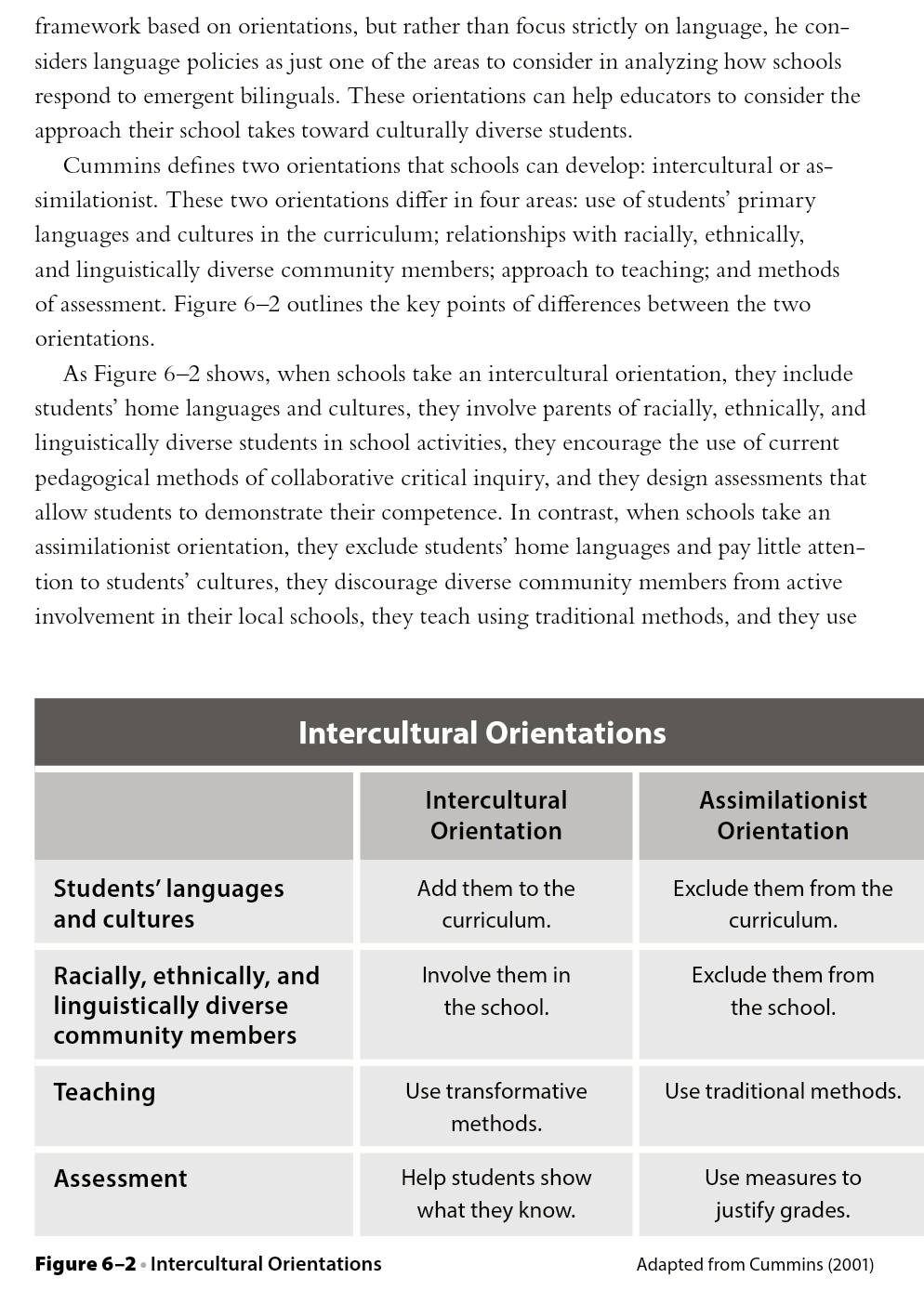

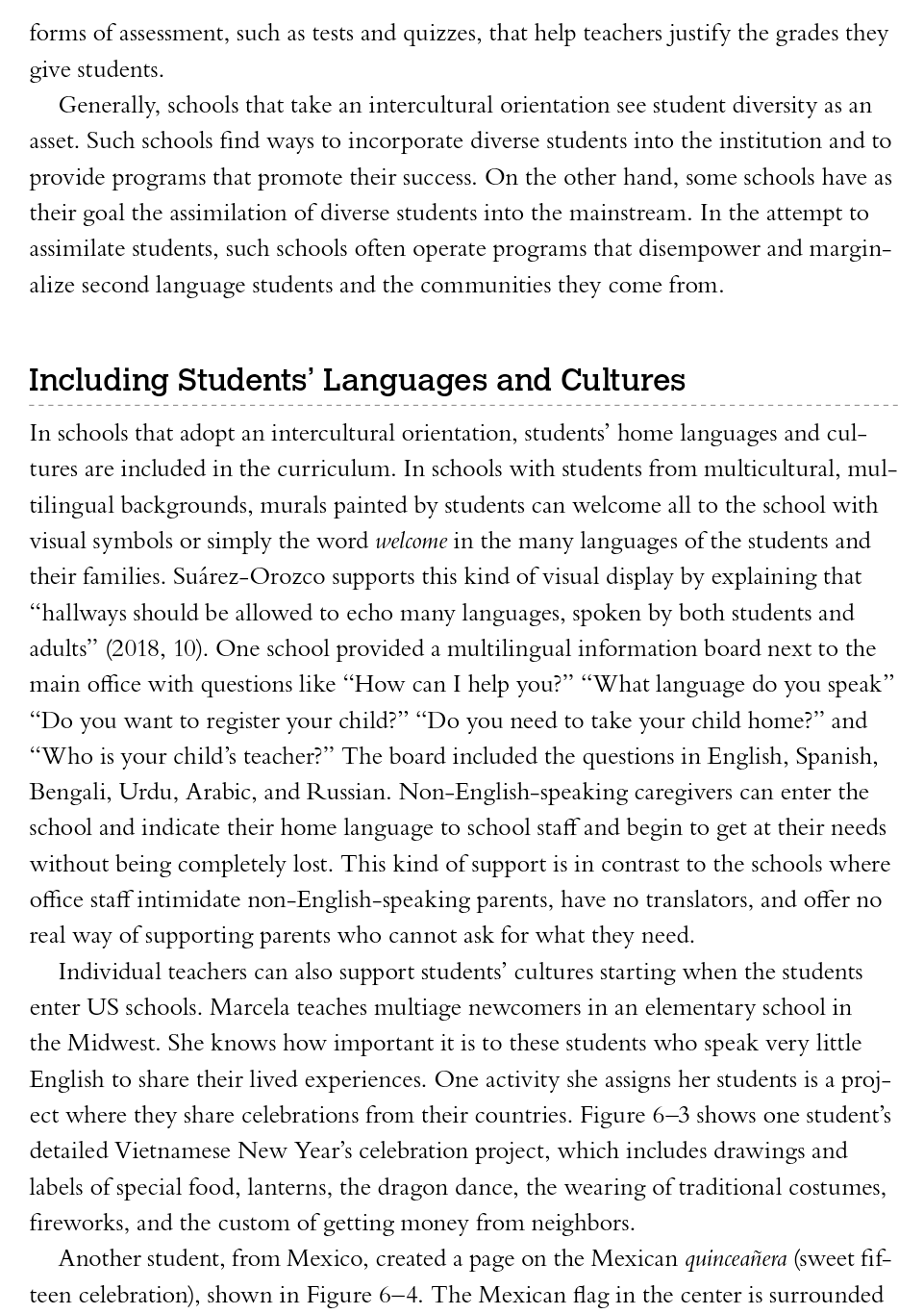

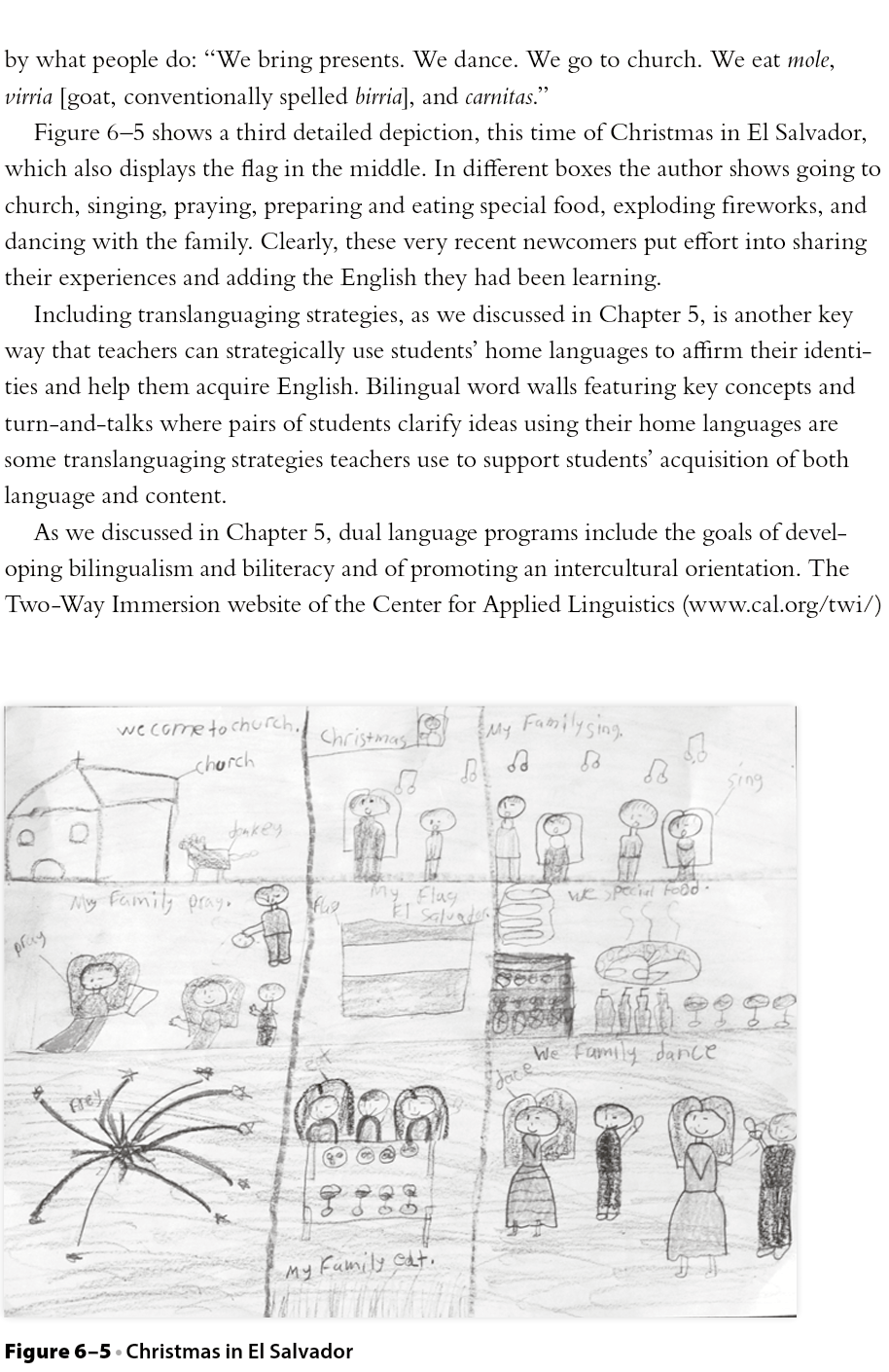

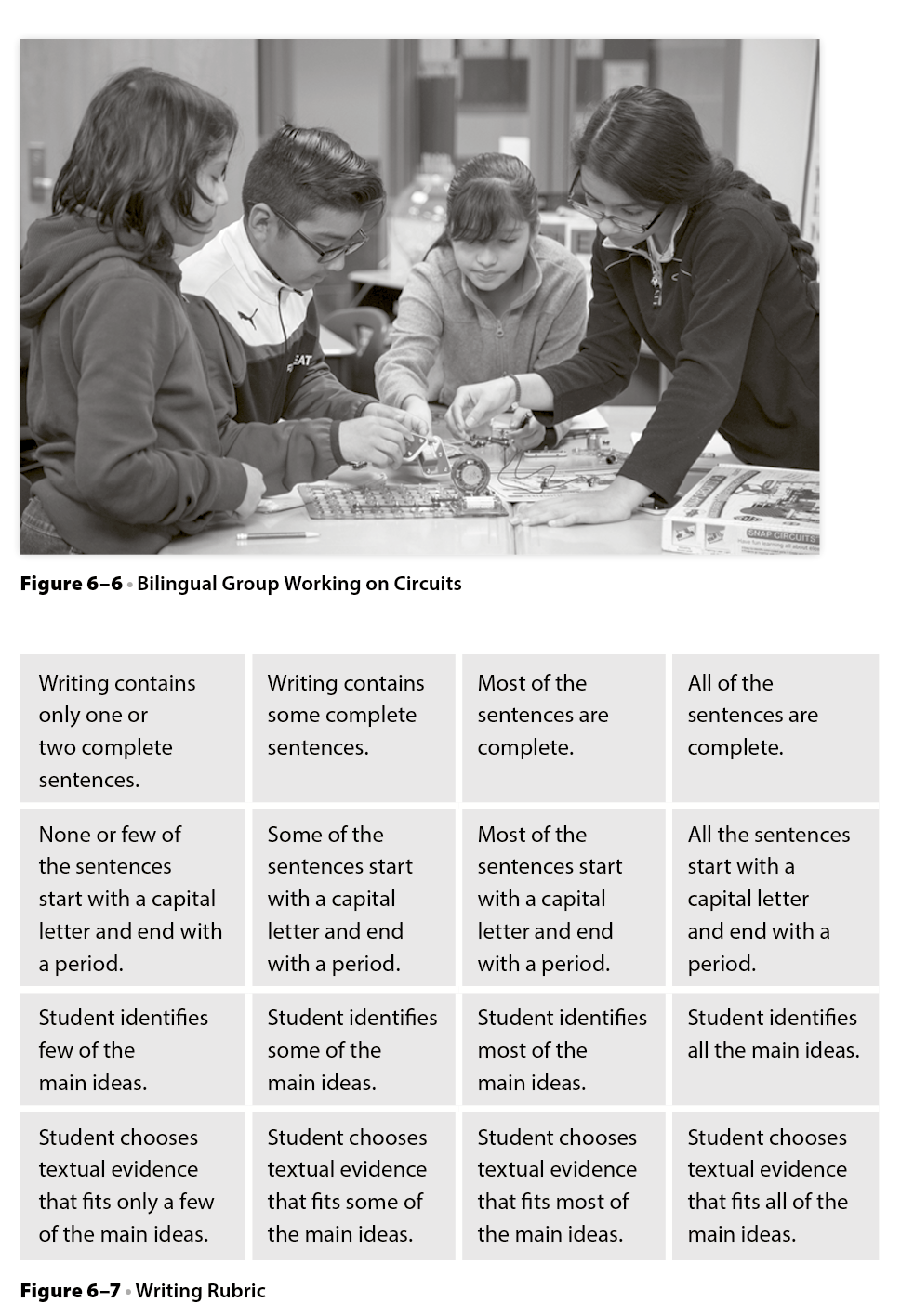

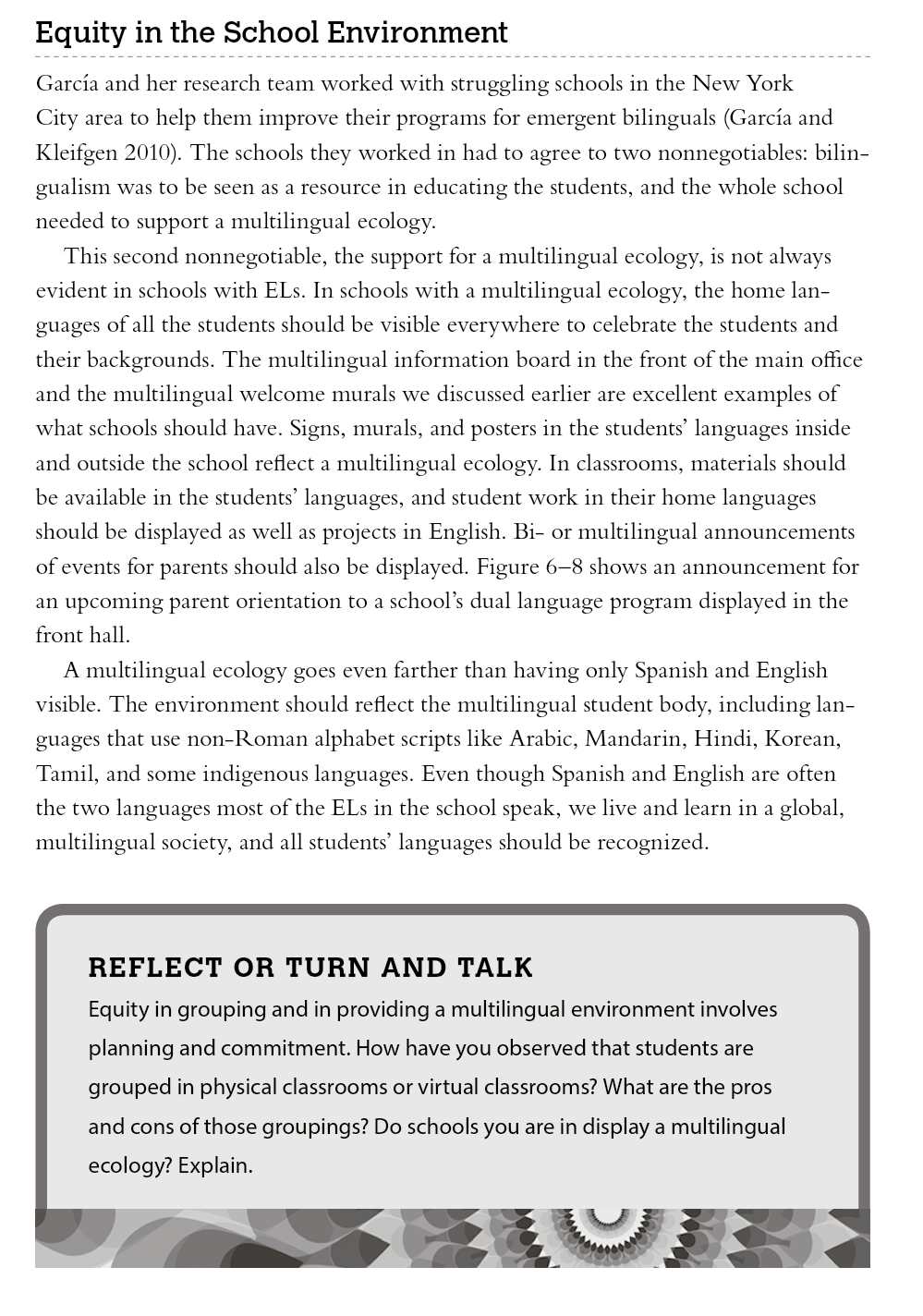

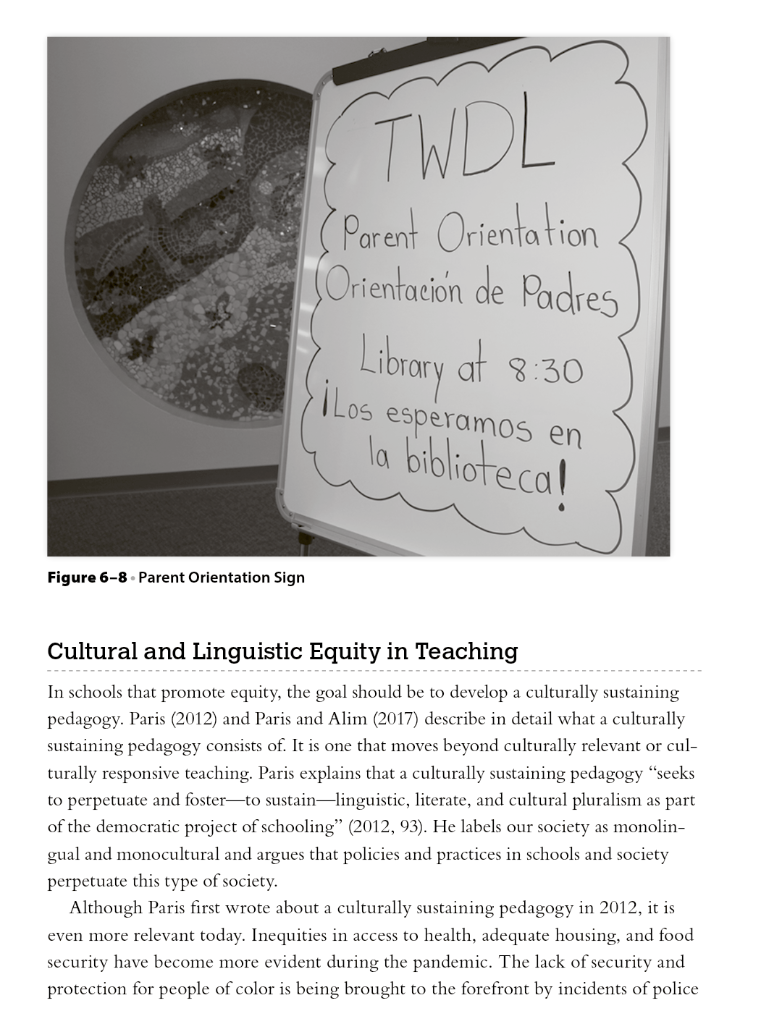

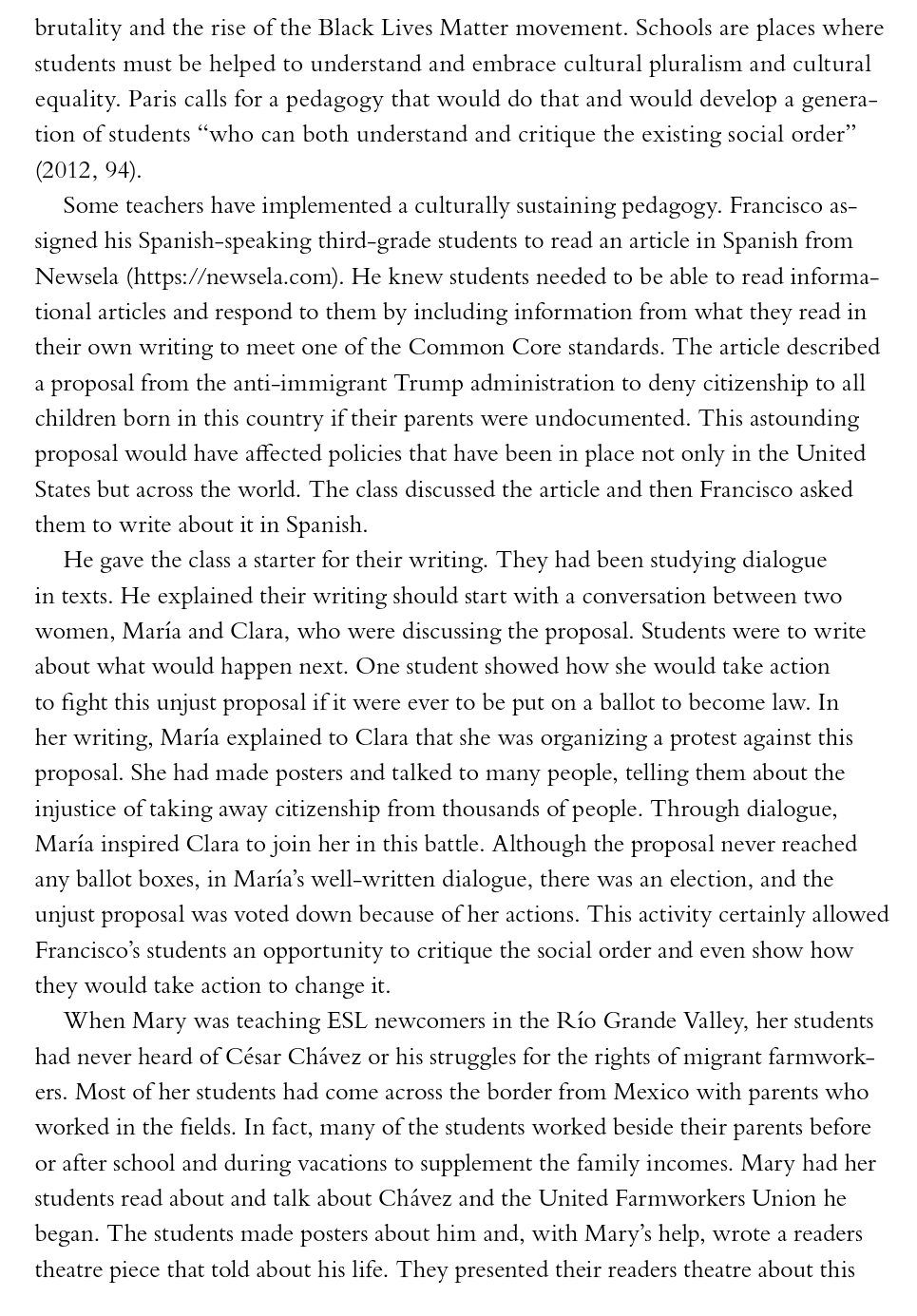

6 How Can Schools Provide Equitable Education for Emergent Bilinguals? Key Points Segregation in education still exists sixty years after Brown v. Board of Education. Equity is not the same as equality. . During COVID-19, treating students of varying racial, ethnic, or linguistic groups equally did not provide equity. Cummins suggests that societal relations and students' identities affect the school success of students in different racial and ethnic groups. Schools can provide equity through an intercultural orientation. Schools should acknowledge and incorporate students' funds of knowledge. A transformative pedagogy supports emergent bilinguals in schools. Teachers should organize groupings of students and the classroom environment to promote equity. Educators of ethnically and racially diverse students should adopt a culturally sustaining pedagogy. In the 1954 landmark Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, segrega- tion in schools was declared unconstitutional. The court determined that segregated education was inherently unequal and created irreversible harm to segregated students. The reality now is that there is still segregation, both economic and racial, in US schools. According to the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) in 2017 white students were a numerical minority in many schools. Between 2000 and 2017 the white popu- lation of students declined by thirteen million to 24.1 million or 48 percent, while at the same time, the Latinx population grew by eleven million, to 13.6 million, and made up 27 percent of the entire US school population. The percentage of Black students decreased by 2 million to 7.7 million. The Asian population was five million and made up 5 percent of the total, and two million students in schools were consid- ered multiracial. Since 1954 many areas the country have remained or returned to schools that keep students separate by race through a series of Supreme Court deci- sions that overturned desegregation orders across the country (Frankenberg et al. 2019). This has resulted in many racially, ethnically, or linguistically diverse students attending ghettoized schools in poor communities. Research shows that children living in poverty are more likely to show lower- than-average academic performance from kindergarten through high school and have lower-than-average school completion rates (de Brey et al. 2019a). In 2016, 15 percent of all children under the age of eighteen were living in poverty. Significantly more of these children are Black or Latinx and fewer are Asian or white. Racial and Ethnic Diversity in US Schools While the students in schools are much more diverse, schools are not. White stu- dents, on average, attend a school in which 69 percent of the students are white," according to Frankenberg and colleagues (2019, 4), and 55 percent of Latinx students attend schools with other Latinx students and Black students. Asian students attend schools where the student population is 24 percent Asian. White and Asian students are least likely to attend schools with Black and Latinx students. The landscape of school diversity is continually changing. In California, for example, there are already more Latinx students than white students. White students make up only one-fourth of the students in the state. In the South a growing number of schools that in the past had few students of color now have a majority of Latinx, Black, Asian, and multiracial students. Researchers, including economists, are calling for schools to prepare students to live and work effectively in extremely multiracial communities (Frankenberg et al. 2019, 7), but schools in many areas remain segregated. For example, many ELs live in poverty and attend schools with other racially, ethnically, or linguistically diverse students. According to de Brey and colleagues (2019b), in 2015 ELs in US schools made up almost 10 percent of all students, and of that 10 percent, 75 percent were Latinx, with Asian ELs making up the second largest percent. Other racial groups among ELs included white students at 6.1 percent and Black ELs at 3.7 percent. Native American and Alaska Native Americans group at 10.5 percent. These and Pacific Islanders were at a smaller percentage, less than 1 groups of students tend to attend inner-city schools with each other and do not have teachers who reflect their backgrounds, which we discuss in the next section. Teachers, Race, and Equity Research has shown that having a teacher of the same race or ethnicity can have a positive impact on a student's attitudes, motivation, and achievement, and racially and ethnically diverse teachers may have more positive expectations for racially, ethni- cally, or linguistically diverse students' achievement than white teachers (Egalite and Kisida 2018). According to de Brey and colleagues (2019c), in public schools in 201516, the percentage of white teachers in US schools was 80 percent while the percentage of Black teachers and Hispanic teachers was 7 and 9 percent, respectively. Only 2 percent of teachers were Asian nationwide, and teachers who were Native Americans, Pacific Islanders, and other related groups made up 1 percent or less of the total teacher population. The percentage of diverse teachers was higher in schools with more diversity, but white teachers were the majority even in most diverse schools, except in schools with very diverse student bodies (de Brey et al. 2019c). Schools with a student body that had 90 percent racial or ethnic diversity had the highest level of diversity among teachers at 55 percent, while in schools with less than 10 percent diverse students, only percent or fewer of their teachers were racially diverse. When teachers are Hispanic, Asian, or from other racial or ethnic groups, they tend to have less experience, some- times fewer than three years, and fewer advanced degrees, according to the report by de Brey and his colleagues. Gndara and Mordechay (2017) discuss the importance of teachers for the large number of Latinx students in US schools. The researchers found that in schools where at least a quarter of the students were Latinx, fewer than 8 percent of the teachers were Latinx. The research showed that the more Latinx teachers young Latinas have, the more likely they are to go to college, and this was related to the comfort they felt in talking to someone who was likely to understand their circumstances and who could talk to their parents (154). Gndara and Mordechay also discuss the teacher shortage in areas with large num- bers of Latinx students. In California, where more than half of the students are Latinx, only about 18 percent of the teachers are of the same ethnic background. While 2 research shows that dual language programs serve many Latinx students well, there is a massive shortage of bilingual teachers for these programs. In fact, Gndara and Mor- dechay report that only 5 percent of the Spanish-speaking bilingual students in the 5 state have teachers who are bilingual, largely because of Proposition 227, which made bilingual education illegal until the 2016 passage of Proposition 58 allowed schools to offer multilingual programs. Many Latinx teacher education candidates do not have the academic Spanish they need to teach beyond kindergarten because their instruc- tion in schools in the state was all in English. Demographic data from a 201516 report (Gndara and Mordechay 2017) shows school location made a difference in the diversity of teachers. For example, city schools had a higher percentage of racial, ethnic, and linguistic groups at 31 percent, compared with town schools at 12 percent and rural schools at 11 percent. Suburban schools, however, did have more diverse teachers. Reports show that 18 percent of their teachers were nonwhite. Overall, across the country, then, the racial and ethnic diversity of students is not reflected in the teaching force. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK Which of the demographics related to diversity in schools surprised you? How do you think these demographics inform schools and teachers? How are the schools that you are familiar with or work in reflected in these demographics? Equality Versus Equity Equity is not the same as equality. The claim is that all people in the US have equal opportunities and equal access. So, for example, a company that advertises itself as an equal opportunity employer should evaluate all who apply to work based on their qualifications, not their sex, sexual orientation, age, or ethnicity. Although this is a goal, it has not yet been realized. Black and women candidates are not hired or promoted equally with white candidates. The recent Black Lives Matter movement is based on the fact that persons of color and whites are not treated equally by the police. Taking into consideration the demographic data we shared earlier, it is clear that not all students have equal educational opportunities. When emergent bilinguals attend schools with a large number of ethnically diverse students in poor neighbor- hoods, and in which teachers do not reflect the ethnicity of their students and are not as experienced as teachers in schools that are less diverse, there is a lack of equal op- portunity. Kozol (1991) has documented the difference in funding for schools and the difference in school facilities and resources in districts based on the wealth of people in the district and the tax base of properties there, even in districts that are not far apart geographically. Even in schools that provide equal resources, English learners may not receive equitable education. While equality aims at providing equal opportunity, the goal of equity is equal outcomes. In the 1974 Lau v. Nichols case, the Chinese-speaking students had the same teachers and used the same textbooks as native English speakers. However, since they did not speak English, they could not access the curriculum or understand the teachers. As a result, they did not achieve equal outcomes. They had equal opportunities, but the instruction did not constitute equitable education. Equity often involves removing institutional barriers that prevent some students from learning even when they are given equal opportunities. In this case, changing the requirements for language of instruction provided the Chinese students an equitable education. Gndara and Mordechay (2017) report that Latinx students are increasingly in places where there is little infrastructure to support their educational needs. The segregation of Latinx students is now the most severe of any group and typically involves a very high concentration of poverty (Frankenberg et al. 2019, 9). For these students and all students from diverse groups, there need to be more socioemotional support systems. For example, explicitly negative statements toward immigrants and certain racial and ethnic groups beginning with Donald Trump's 2016 presidential campaign have had negative consequences (Frankenberg et al. 2019). In 2020, racial and ethnic tensions exploded after the killing of George Floyd, accompanied by the reignition of the pain and fear surrounding the many killings of people of color by the police and others. The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement soon became the Black and Brown Lives Matter movement. In addition, Asian Americans were targeted because Presi- dent Trump blamed China for the spread of COVID-19, and, thus, any Asian was fair game to be blamed and sometimes attacked because of the pandemic. These events al- lowed for xenophobia to become accepted and encouraged in some circles and created fear among ethnically diverse students and their families. Research studies have shown that the current atmosphere has exacerbated racial and ethnic problems in schools, including noticeable changes in school climate. Equality Versus Equity During COVID-19 When states across the country declared that all but essential services should close, that included all schools: elementary-, secondary-, and university-level institutions. That meant that instruction was going to be given online, a decision that gave many educators only a weekend to reorganize and revisualize the curriculum. The clo- sures were applied equally across most communities, and administrators and teachers scrambled to deliver instruction virtually. Most students in middle- and upper- class homes had computers or tablets and internet connections. For the most part, parents were available to support these students. However, although all students in a school or district were given the same curriculum, there was a lack of equity. In many homes of emergent bilinguals, there were no computers and no access to the internet. Teachers soon discovered that some students lived in homes with a single parent and several siblings and many other homes included multigenerational family mem- bers or more than one family sharing a home. In these settings, often the only means of communication with schools was a cell phone shared by several family members. While this situation could not be remedied in some districts, schools in many parts of the country responded by supplying tablets, but then found they needed to also find ways to provide internet access. In some areas hot spots were supplied where needed. However, even these supports did not give many emergent bilinguals access. The LA Times reported that over fifty thousand middle and high school students in Los Angeles did not participate on the school's main platform for virtual classrooms after schools closed in March 2020 (Esquivel and Blume 2020). Black and Latinx students participated between 10 and 20 percentage points lower than white and Asian peers. English learners, students with disabilities, students who are homeless, and students in foster care also had lower participation rates. In a policy brief from the Migration Policy Institute (Sugarman and Lazarn 2020), the authors state the COVID-19 pandemic has brought into sharp relief the inequities that English Learners (ELs) and children from immigrant families expe- rience in U.S. schools and in their communities. They explain that despite great efforts by educators, in spring 2020 the school systems with the largest number of ELs reported that less than half the ELs were logging in to online instruction. They point out among the most significant barriers to ELs' participation were a lack of access to digital devices and broadband; parents' limited capacity to support home learning; inadequate remote learning resources and training for teachers; and school-family language barriers. The report concludes that if schools continue distance learning through the fall, many students will lose 7 to 11 months of learn- ing. In addition, for many families of ELs, the pandemic and accompanied school building closures have compromised their access to food and income security as well as social and mental health supports. There were different issues beyond access for many students. When teachers gave assignments, neither students nor their parents had had enough experience with tech- nology to help students attend meetings online or upload assignments on platforms like Google Classroom. In addition, if there were several children in the family, the tablets had to be shared (LaFave 2020). Parents who might have helped were often absent because they were essential workers, including those working in health care, on farms, in meatpacking plants, in grocery stores, or in delivery services. For immigrant parents there was often the added problem of not reading and writing English profi- ciently enough to be of assistance to their children. Even when parents or relatives in these families could help their children, other issues took priority. Family members got sick or lost jobs or both. One administra- tor in New York City explained in a Zoom meeting that her main priorities were not getting instruction to families but getting food to them and helping them with funeral arrangements. During a recent TESOL presentation an administrator from a school district in Connecticut pointed out that the online plan for the district involved sending home lesson packets for students to complete (Becker 2020). Packets are not generally effec- tive for teaching students and clearly do not provide equity for ELs. In this district, since they had materials only for mainstream students, there were no accommodations for English learners. This created a situation like that of the Lau v. Nichols case in 1974. Beginning-level ELs had a hard time understanding the instructions on the packets, and many parents could not read English, so they could not help. The district was able to translate the packets into Spanish, and this helped many ELs since many of them spoke Spanish, but not all did. The district made many other accommodations, such as having social workers visit homes of students who were not participating in the pro- gram, but it is evident that many challenges face school districts, even as they continue to improve services for emergent bilinguals. Another presentation at this TESOL session involved EL specialists working in Missouri (Hellman et al. 2020). They conducted a survey of teachers with follow- up. In addition to EL families lacking internet access or devices, they found that EL families were not always informed on how to proceed after schools suspended operations. Information was provided on the school website, but it was difficult to find any EL supports. There were problems in connecting with EL families. Only 62 percent of the teachers connected with every EL family, and 43 percent did not connect with every EL student. The district also lacked good translation services for families of ELs who did not speak Spanish, such as their Karen population. Teach- ers made great efforts to support ELs, but many ELs did not participate in instruc- tion because of the problems with communication and the lack of any clear plan by the district. Again, as this example shows, lack of online schooling resources for ELs in many districts across the country results in a lack of equitable education for these students. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK We explained the difference between equality and equity and some examples of lack of equity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consider your present context. Can you think of an example where equality in schools you know does not provide equity for emergent bilinguals? Do your administrators consider equity when they make decisions that affect racially, ethnically, or linguistically diverse students? How? In a climate rife with racial and ethnic tensions and students who are not equita- bly served, educators need some guidance in how to approach the teaching of emer- gent bilinguals. They also need some practical suggestions for what they can do as they teach these students. We present two different frameworks from Cummins that look at how students are viewed and the policies toward them that have led to those views. The first is his societal relations, identity negotiation, and academic achieve- ment framework and the second is his intercultural orientations framework (Cummins 2001, 2009). Societal Relations and Equity for Emergent Bilinguals Cummins (2009) explains that society often exerts negative power over ethnic and racial groups. These powers are evident in experiences such as police violence and frequent racial slurs and threats. These types of events negatively impact the school achievement of racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse students. When immi- grant emergent bilingual children see political figures threatening to deport their rela- tives and hear themselves called derogatory names, children sometimes fear even going to school (Saxon 2018). These societal conditions can influence how teachers interact positively or negatively with linguistically and culturally diverse students. Coercive and Collaborative Relations of Power According to Cummins (2001, 2009), when teachers interact with students, they create interpersonal spaces in which learning happens and students identities are negotiated. What students learn and how teachers either support their identities or negate them is critical to emergent bilingual students. Teachers either reinforce the coercive relations of power that negatively affect their students or promote collabora- tive relations of power. Coercive relations of power develop when the school or teach- ers overtly or covertly view certain students as less capable and even less worthy. Over the years we have heard teachers and administrators talk about those chil- dren who don't have a good home, don't have parents who care, aren't really trying, interact only with other students who don't speak English, or are maana students. One hears things like What can you expect of Pancho? His family doesn't speak English at home. In coercive relations of power, the dominant group defines the subordinated group as inferior and tends to blame the victim (Cummins 2001). Teach- ers have low expectations of these students and provide fewer opportunities for their academic development. We remember observing a high school ESL class where during the entire class pe- riod, the teacher gave students five vocabulary words to work with: first they repeated the words, then copied their definitions, and then completed a fill-in-the-blanks sheet. Students were bored, tended not to pay attention, and knew they were not being challenged. It was painful to sit and watch this class. When asked about readings and other activities, the teacher pointed to some anthologies but explained, They really a can't read them. We don't use them very often. When we try activities, they don't understand. Valds (2001) has written in detail about cases of students who are given placements and instruction that result in their never advancing academically. Many of these students simply drop out. In contrast to coercive power relations, collaborative relations of power assume that students can be empowered learners when their identities are affirmed, and they work collaboratively with the teacher and classmates to learn together. Instead of worksheets and boring repetition, students read meaningful, grade-appropriate texts together, are encouraged to discuss and write in their home languages as well as in English, and are provided opportunities to respond in a variety of ways to show what they know and understand. This can include artwork, reports based on inter- net searches, and group sharing. One teacher had her year one ESL students do a cool country report. They drew a map of their home country and drew and colored their flag, listed key points of interest in a travel brochure, identified products or industries within the country, and wrote about holidays and favorite foods. Drawing on the content from their reports, they made silhouettes of their faces and decorated them to make cultural visuals of themselves that included a map of their country, words in their home language, their flag, drawings of points of interest, and religious symbols. In her silhouette, a girl from India wrote in Hindi and Tamil, drew the Taj Mahal, and included an altar with an elephant with a marigold necklace. These activities helped students develop both literacy and oral language skills while affirming their bilin- gual identities. As we described in Chapter 5, Mary and Elizabeth had their university students who were studying to become bilingual teachers make cultural mandalas in multi- cultural small groups. They asked the students to list characteristics of their identity with their culture and families. After they had completed their cultural mandalas, the whole class shared their personal characteristics on the large classroom whiteboard. This powerful cultural graffiti board, shown in Figure 61, celebrated and reflected the class' diversity by including drawings as well as phrases in English and students' home languages. Francisco, a teacher from El Salvador, read his bilingual third graders a story he had written about his childhood in rural El Salvador. The students asked him about the childhood memories he described, and he provided additional details about grow- ing up in poverty in his home country. He then asked the children to write about an incident from their own childhood or to interview their parents or grandparents and DANAS family and econo Maria Tela "Dodgers Christmas/hondays UPOSADA ALI w/ family "Were not allow a without ang dad ( Califorsving What's - = 0 9+102 21 famikes to! TV Shows Nyob Zoo! Kuv you Hmoob at Costa Big 1 What's Juan Gabriele Menu Christmas/hornys 9+10? 1 ul family of POSADAS Sports Oto! TV Shows . CALIENTE! 70 Cor-a Rosca Quineriera Suv you Hmoob RICE Gordana lak B-day TEEN UN DIA DE LOS MUERTOS movie SPICY papy Quirkeera Figure 6-1 Cultural Graffiti Board RICE DIA DE LOS HALON MUERTOS write those experiences. The teacher's sharing allowed students to reflect on their own experiences and those of their relatives and share them. Students spent a great deal of energy on this project, which validated who they were and, for many, helped them appreciate and celebrate their relatives' lived experiences, something they had never done before. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK Think of some examples of coercive relations of power that you see in your community and in a school you know. How can or should your community and school implement collaborative relations of power instead? Intercultural Orientations for Education Earlier we discussed Ruz's general orientations toward language. These orienta- tions have led to the establishment of different kinds of programs that support the development of home languages for ELs. Cummins (2001, 2009) has also developed a framework based on orientations, but rather than focus strictly on language, he con- siders language policies as just one of the areas to consider in analyzing how schools respond to emergent bilinguals. These orientations can help educators to consider the approach their school takes toward culturally diverse students. Cummins defines two orientations that schools can develop: intercultural or as- similationist. These two orientations differ in four areas: use of students' primary languages and cultures in the curriculum; relationships with racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse community members; approach to teaching; and methods of assessment. Figure 62 outlines the key points of differences between the two orientations. As Figure 62 shows, when schools take an intercultural orientation, they include students' home languages and cultures, they involve parents of racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse students in school activities, they encourage the use of current pedagogical methods of collaborative critical inquiry, and they design assessments that allow students to demonstrate their competence. In contrast, when schools take an assimilationist orientation, they exclude students' home languages and pay little atten- tion to students' cultures, they discourage diverse community members from active involvement in their local schools, they teach using traditional methods, and they use Intercultural Orientations Intercultural Orientation Assimilationist Orientation Students' languages and cultures Add them to the curriculum. Exclude them from the curriculum. Racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse community members Involve them in the school. Exclude them from the school. Teaching Use traditional methods. Use transformative methods. Assessment Help students show what they know. Use measures to justify grades. Figure 6-2 Intercultural Orientations Adapted from Cummins (2001) forms of assessment, such as tests and quizzes, that help teachers justify the grades they give students. Generally, schools that take an intercultural orientation see student diversity as an asset. Such schools find ways to incorporate diverse students into the institution and to provide programs that promote their success. On the other hand, some schools have as their goal the assimilation of diverse students into the mainstream. In the attempt to assimilate students, such schools often operate programs that disempower and margin- alize second language students and the communities they come from. Including Students' Languages and Cultures In schools that adopt an intercultural orientation, students' home languages and cul- tures are included in the curriculum. In schools with students from multicultural, mul- tilingual backgrounds, murals painted by students can welcome all to the school with visual symbols or simply the word welcome in the many languages of the students and their families. Surez-Orozco supports this kind of visual display by explaining that hallways should be allowed to echo many languages, spoken by both students and adults (2018, 10). One school provided a multilingual information board next to the main office with questions like How can I help you? What language do you speak Do you want to register your child? Do you need to take your child home? and Who is your child's teacher? The board included the questions in English, Spanish, Bengali, Urdu, Arabic, and Russian. Non-English-speaking caregivers can enter the school and indicate their home language to school staff and begin to get at their needs without being completely lost. This kind of support is in contrast to the schools where office staff intimidate non-English-speaking parents, have no translators, and offer no real way of supporting parents who cannot ask for what they need. Individual teachers can also support students' cultures starting when the students enter US schools. Marcela teaches multiage newcomers in an elementary school in the Midwest. She knows how important it is to these students who speak very little English to share their lived experiences. One activity she assigns her students is a proj- ect where they share celebrations from their countries. Figure 63 shows one student's detailed Vietnamese New Year's celebration project, which includes drawings and labels of special food, lanterns, the dragon dance, the wearing of traditional costumes, fireworks, and the custom of getting money from neighbors. Another student, from Mexico, created a page on the Mexican quinceaera (sweet fif- teen celebration), shown in Figure 64. The Mexican flag in the center is surrounded by what people do: We bring presents. We dance. We go to church. We eat mole, virria (goat, conventionally spelled birria), and carnitas. Figure 65 shows a third detailed depiction, this time of Christmas in El Salvador, which also displays the flag in the middle. In different boxes the author shows going to church, singing, praying, preparing and eating special food, exploding fireworks, and dancing with the family. Clearly, these very recent newcomers put effort into sharing their experiences and adding the English they had been learning. Including translanguaging strategies, as we discussed in Chapter 5, is another key way that teachers can strategically use students' home languages to affirm their identi- ties and help them acquire English. Bilingual word walls featuring key concepts and turn-and-talks where pairs of students clarify ideas using their home languages are some translanguaging strategies teachers use to support students' acquisition of both language and content. As we discussed in Chapter 5, dual language programs include the goals of devel- oping bilingualism and biliteracy and of promoting an intercultural orientation. The Two-Way Immersion website of the Center for Applied Linguistics (www.cal.org/twi/) we come to church, Christmas les funy Family sing. -church so Jonkey Ning family prayo Flag wpecial Food El Salvador pray See og We Family dance dace fre Qad 211 MY family eat. Figure 6-5 Christmas in El Salvador lists the three goals of dual language programs: develop high levels of language pro- ficiency and literacy in both program languages, demonstrate high levels of academic achievement, and develop an appreciation for and an understanding of diverse cultures (italics added). By their nature, well-conceived bilingual programs promote an intercultural orientation because they promote and celebrate students' home languages and validate their identity. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK What are some ways that your school or a school you know is including students' cultures and languages? Be specific. What are some ideas you have to increase the inclusion of students' cultures and languages? DRAWING ON CULTURAL FUNDS OF KNOWLEDGE In schools that have an intercultural orientation, teachers draw on students' funds of knowledge as they plan their curriculum. Moll and his colleagues (1992) engaged both university researchers and classroom teachers in projects aimed at discovering students' funds of knowledgethe knowledge and skills that are developed in homes and communities. Their research, conducted by teachers, took place in the homes of students, many of whom were immigrants. The research was designed to learn from the students and parents and to discover their funds of knowledge. The researchers discovered the strategies and skills that families develop to function effectively. For example, families know whom to call for medical advice or whom to talk to if their car needs repair. Two clear examples of funds of knowledge that immigrants have come to mind. In teaching about health, teachers should be aware of home remedies and community expertise and practices. Our son-in-law's mother lives in California near relatives and friends who are all from El Salvador or Mexico. She is known as the woman to call for a sobada (massage) when one has aches and pains. She knows how to vary her massages to the condition of the person, what salves to use, and when to use heat. She even knows how to use cupping, originally an ancient therapy developed in Asia. She does the massages, but she turns to others in the community to find who will repair her car or solve her plumbing problem at minimal cost. a Sandra, who was teaching in a farming community in the central valley of Califor- nia, knew how to draw on funds of knowledge in her teaching. She developed a unit on seeds, plants, plant growth, and nutrition. She began the unit by having students bring in seeds their parents used in their work and home gardens. Then, students in- terviewed their parents about how to plant and cultivate the seeds. One mother came to class and talked to the students about her large garden, which included tomatoes, chiles, squash, chayote, and beans. She also talked about herbs she grew to make teas that were used when family members got sick. Bennett (2020) has suggested that teachers can draw on their students' funds of knowledge by making home visits and by having conversations with students about what they and their families do at home, having students bring in artifacts that con- nect to what the class is learning, having students interview family members and write about them, and having students share about their countries of origin. Teachers who do these kinds of activities show they are teaching using an intercultural rather than an assimilationist orientation. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK Explain in your own words what funds of knowledge are and why they are important for teachers. How have you or teachers you know drawn upon your emergent bilinguals' funds of knowledge? Involving Racially, Ethnically, and Linguistically Diverse Community Members in the School A second characteristic of schools that adopt an intercultural orientation is that they involve racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse community members in school activities. These schools develop programs that encourage collaboration between the school and the community. In the United States over 25 percent of the children under eighteen, or 18.7 million children, have a parent who is an immigrant (Surez-Orozco and Marks 2016). With these numbers in mind, schools should take an intercultural orientation and foster strong relationships with all parents, including parents of emer- gent bilinguals. All parents want their children to be successful. However, some parents of English language learners do not appear to show interest in their children's school lives. Francisco provides us with some insights into why teachers and administrators might develop the impression that the parents of emergent bilinguals just don't care. In 1989, at age fourteen, Francisco came to the United States from El Salvador, during its period of civil war. Francisco, like many young men his age, was in danger of being conscripted by the army of either side and forced to fight. Concepcin, his mother, viewed his arrival in Fresno as the end of her long struggle to get him to the United States legally. Concepcin spoke no English and had not been educated in El Salvador. She saw her responsibility as making sure Francisco was safe in the United States, and providing food and shelter for him. Once Francisco was in the United States, his job was to succeed hereto accom- plish the American dream. His mother certainly cared about his schooling, but she was not prepared to approach his teachers to discuss his schoolwork and progress. The large inner-city high school of over three thousand was overwhelming to her. She assumed that the school was educating Francisco, and she believed it was the teacher's job to teach and hers to be sure that Francisco was bien educado, meaning respectful and polite. In Concepcin's worldview, it would have been presumptive for her to interfere. In his first year in college, Francisco found the coursework very difficult and was at the point of giving up when his college soccer coach, who could speak Spanish, came to Francisco's home to talk to Concepcin about Francisco's academic struggles. After this visit, Concepcin talked to her son long and hard about the sacrifices she had made to give him this opportunity for an education. Francisco still remembers thinking, You don't know how hard it is. You have no idea." He did not lack respect for his mother. He was simply living in a world that she was not part of and did not understand. She was not a negligent parent. She was just not able to help him with his academic school subjects. Instead, she saw her role as raising him to be respectful, caring for his physical needs, and providing strong encouragement for him to continue his education. Tou, the Hmong student we described in Chapter 2, came from an immigrant family that had suffered greatly because of the move from Southeast Asia to the United States. Tou's parents had separated, and he lived with his father, who could not find work and who did not speak English. His father only came to school for a confer- ence at the request of school personnel. He would probably not have felt comfortable coming to parent meetings or participating in parent groups. a Jos Luis, Guillermo, and Patricia, the three teens from El Salvador, lived by themselves. Their only relative in the United States was their aunt. Unlike Francisco's mother, she was very well educated, studying for a doctorate. She was a wife, a gradu- ate student, and a teacher of Spanish at both the university where she studied and the local community college. Like Tou's father, she would come to a school meeting, but only if a serious problem arose. She provided the teens with family, love, and shelter. Her niece and nephews knew what they needed to do to succeed, and it was up to them to do it. Even though she was involved in education, she had not attended public schools in the United States. In El Salvador, where she had been educated, parents were not expected to be involved in their children's schooling. As a result, she did not see her role as helping her nephews and niece with their schooling. Parents of English language learners like Francisco, Tou, and the three siblings from El Salvador realize that school may be the only road to success for the young people. Sometimes they do not know how to help their children succeed, especially if they do not speak English and have had very little schooling themselves. Even if they received an education, it may have been in a school system very different from the system in this country, and they might not understand the expectations of their role as parents here. For that reason, in schools with an intercultural orientation, extra efforts are made to involve parents. This includes hiring liaisons who visit the homes and encourage the families to come to parent meetings at the school, conducting parent meetings in the students' home languages, and sending out notices and invitations to meetings in the home languages of all the students. In addition, these schools have a plan for welcoming the parents at the school. Individual teachers make it a point to meet the parents and maintain contact with them. For example, in one school, a second-grade bilingual teacher provided coffee and donuts for parents before school on Mondays. She found that her Spanish-speaking parents came and talked to her and they were able to solve many issues through this dedicated time. RESEARCH ON TEACHER ATTITUDES TOWARD IMMIGRANT PARENTS In many cases, teachers do not realize that parents of emergent bilinguals may not see their role as becoming involved in their children's schooling. In their research, Surez-Orozco, Surez-Orozco, and Todorova (2008) conducted interviews with seventy-five teachers in seven school districts in different areas of the country to deter- mine their perception of the parents of immigrant adolescents. They asked questions such as, How do you expect parents to support their children's education? They found that many teachers felt that most immigrant parents were not as involved as they should be and that they held low expectations for their children's academic future. The researchers summed up their findings by commenting, Parents who came to school and helped with homework were viewed as concerned parents, whereas parents who did neither were thought to be disinterested and parents of poor students. A teacher shared with us: "Only a minimum percentage of parents get involved in their kid's education and usually the parents that are concerned and get involved are the parents of the students that are doing well in school. Parents that have kids with problems prefer to hide and not get involved. (77) While the Surez-Orozco team found that teachers perceived that parents held low expectations for their children, interviews with the students painted a different picture. The researchers wrote: While overall teachers' assessments of immigrant parents were often patronizing at best and hostile at worst, looking into the eyes of immigrant youth, we found a very different perspective. The vast majority of the children had internalized very high parental expectations for their students' performance. (77) The researchers asked students to complete the question, For my parents, getting good grades is .? (77). Seventy-one percent of the students responded very important and another 22 percent responded important." Even though their children's academic success is important for emergent bilinguals, often they do not understand how school works and how to help their chil- dren with school. Gndara and Contreras, in their study of Latinx students, found this to be the case, even with middle or upper class parents: parents of Latino parents also have less access to information about schooling, even when they are ostensibly from the same social class as white parents. And if they are undocumented, they have much less access to social and health services than a similarly low-income white family. (2009, 83) Valds (1996), in her study of ten migrant families over a three-year period, found that the gap between home and school was, indeed, wide. The school did not understand the families, and the families did not understand the school. She explains the problems in communication from the school's perspective: Schools expected a standard family, a family whose members were educated, who were familiar with how schools worked, and who saw their role as complementing the teacher's in developing children's academic abilities. It did not occur to school personnel that parents might not know the appropriate ways to communicate with the teachers, that they might feel embarrassed about writing notes filled with errors, and that they might not even understand how to interpret their children's report cards. (167) REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK What are the attitudes that teachers you know have expressed about emergent bilingual students' families? What did the stories about Francisco's mother, Tou's father, and the Salvadoran students' aunt tell you about immigrant parents? What did the researchers explain about parents of immigrant students? PARENT EDUCATION PROGRAMS Schools have found it difficult to reach out to immigrant parents in particular, in part because of the issues discussed previously and in part because they do not know what to do or how to do it. Yvonne remembers a rural school district with many migrant children that decided to try something different. The school invited her to give a workshop for parents on how to support their children in reading and present it all in Spanish. The response at the parent meeting was overwhelming. So many Spanish-speaking parents showed up that the officials had to move them to a bigger room. White English-speaking parents complained that they didn't get the same information that the Spanish-speaking parents were getting and resented getting moved to a smaller room. One South Texas border dual language school we worked in pro a class- room especially for parents. There was coffee available and parents brought snacks. At tables the parents and young children sometimes helped teachers with art projects and sometimes talked to the bilingual teachers and administrators who stopped by. The school also provided a Spanish-speaking parent liaison who worked with parents, role- playing scenarios for interacting with their children and with the school. At all times, younger children not yet in school were welcome with parents. Marcelo Suarez-Orozco (2018) encourages schools to offer workshops and webi- nars on topics of interest to immigrant parents in particular. He describes how one Spanish-English bilingual school held weekly meetings in Spanish where staff mem- bers discussed with parents adjustments to life in the United States and gave parents tools to help their children navigate their schooling. This could be especially helpful as technology becomes more important in schooling in this country. If parents see that technology is beyond them and something they cannot do, that leaves students completely on their own at home. To combat this challenge, schools could hold dis- cussions and workshops virtually once they've provided families with the technology they need. With home responsibilities, sessions from home might be more possible than attending events in person. Sessions could help parents understand the different platforms their children are using to do their work. HOME VISITS We discussed earlier how teachers conducting home visits discovered the funds of knowledge that families had. Doing home visits can be part of parent involvement in a school's intercultural orientation. The home and the school can really be two different worlds. To bridge that gap, teachers can carry out home visits. Katherine was in her first year of teaching when she visited her students' homes at the end of the first grading period. Before she went, she complained about the time and effort the visits were going to take. Afterward, however, she realized how much she had learned. Her students' homes were modest, located around the small farming community where she taught. She came away from each visit with respect for both the parents and the children. She saw that many parents were struggling to get food on the table for their children. She found out that many of her first-grade children often took on responsibilities at home while parents and older siblings worked extra hours to make ends meet. Perhaps what touched her most, however, were the eagerness and re- spect with which she was received in homes, and the interest, pride, and hope parents showed for their children's futures. Even when it is not a school requirement, several teachers we work with have made home visits because this has helped them understand their students and parents so much better. Two weeks before school starts, Peter sends an introductory letter to all the children in his class and to their parents. He tells them in the letter that he will be a visiting their home to get to know them in the following week. Then he makes short visits to as many homes as possible. Even though he does not speak the first languages of many of his students, he is welcomed into the homes and has a chance to see some- thing of his students' home lives. Peter has found that those visits have a made a big difference for students during their first days of school, and that after meeting their children's teacher, parents are much more comfortable with both him and the school. The visits have often given him ideas about how parents can become involved in his class. One parent, for in- stance, played a musical instrument, and another did wood carving. Peter would never have known this had he not been in the students' homes, and since the parents had met him, they were more responsive to his invitations to come and share their skills. This personal contact, undertaken before school even starts, has made a big difference for Peter in the home-school relationship. In some districts, teachers go out on home visits in pairs to support each other. After the visits they share what they have learned with their partner and other col- leagues. This approach has been quite successful. ACTIVITIES FOR BOOSTING HOME-LANGUAGE LITERACY In the past, some schools have encouraged parents to speak English to their children at home. However, when parents talk to their children and read and write with them in their first language at home, communication is more natural. We discussed translanguaging in Chapter 5. Encouraging translanguaging draws on students' linguistic repertoire and leads to more school success. For example, a good activ- ity to encourage children to do at home is to make books in the home language. Especially as students are doing work virtually from home, making books on differ- ent topics allows students to develop language and at the same time creates home- school connections. Teachers could ask students to notice what people read in their homes. This could include conventional things like magazines and books but also ads, packages, letters, recipes, spice jars and cans, and cell phones. Students could take pictures of people in the household reading those things and create a book to share online with the teacher and classmates. They could make a similar book by taking pictures of places in the neighborhood or parts of an apartment building, labeling the pictures, and assembling them into a book. Yvonne has developed some practical suggestions for what parents can do with their children in their home language, even when parents are not literate in their native lan- guage. These suggestions can be worded in ways that give parents ideas for what they can do with their children at home in the home language to support their children's literacy development in the home language and English. a 1. Talking. Parents who have conversations with their children help them to think and to explore their world. Parents should talk to students as they shop, explaining why they are choosing different products, or they could point out plants in the neighborhood or in the garden. They can discuss a phone conversation with a family member or talk about a job they have. In this process children learn to use language for a variety of purposes. 2. Reading. Parents who read with their children and take them to the library give them experiences with books that they need for school success. If parents are not confident readers, they can ask their children to do the reading, or parents and children can follow a story while listening together to a recorded reading or audiobook. Some websites have read- alouds available in different languages. See, for example, Audible (https:// stories.audible.com/discovery) and click on any of the languages listed across the top. If the children read a book in English to their parents or if the children and parents listen to an English audiobook, the children can then explain the story to the parents, and they can discuss it in their home language as they look at the pictures. A study conducted in six inner-city schools in London (Tizard, Schofield, and Hewison 1982) investigated the benefits of having children from two schools take books home each day to read to their parents. They compared the reading improvement of this group with another group from two different schools that received extra reading support from a well-trained literacy coach and with a third group from two other schools that received no extra help. Many of the parents of the children who took books home were illiterate or did not speak English. Despite this, the children who read to parents at home made greater gains in reading than the other two groups. The gains were greatest among children in the group who were having initial problems with reading. This group also showed greater interest in school and were better behaved. This study clearly demonstrated the benefits of having children take home books to read to their parents. 3. Writing. Parents who encourage their children to draw and write teach them to express themselves in writing. Parents can also make children aware that adults use writing for a variety of purposes every day, including writing letters, making out checks, jotting notes, and making shopping lists. Even if parents do not write frequently themselves, they can have writing materials including paper and marking pens around for children during playtime. a a Educators at schools that take an intercultural orientation try different approaches to involve the parents of emergent bilinguals. A good first step is to listen to the parents and encourage them to voice their concerns and what their needs are either during meetings at school, through check-in phone calls, or through home visits. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK Yvonne had three ideas parents of emergent bilinguals could implement to support their students literacy. Can you suggest other ways parents can support their children's literacy? Do you understand how using the home language will support literacy in English? Explain. Implementing Transformative Pedagogy A third characteristic of schools that take an intercultural orientation is that they implement a transformative pedagogy. As Cummins (2009) explains, there are two main components of transformative pedagogy. The first is identity investment in learning and the second involves negotiation of identity to encourage engagement. In Chapter 5 we discussed Mary's culture mandala and cultural Venn activities. Both encouraged identity investment and engaged her students. Mary's students were older and more proficient, but Marcela engaged her lower-elementary newcomers in similar activities. The drawings of cultural celebrations was one, but she also had students make elaborate posters to display during a whole-school fair. These posters included a world map indicating their home country and the United States. Next to the map, they identified the distance from their home countries to the United States and how they traveled to the United States. They included their flag and wrote why they came to America. In a Venn diagram they compared their home countries with America. They posted a bilingual list of key words of their choice in their home languages and the English translations. On another part of the poster, students drew and listed foods from their countries. In one corner of the poster, they attached a paper doll figure in traditional dress from their country. When Sandra had her multiage fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-grade ESL students study seeds, plants, and nutrition, she was drawing on their experiences and their knowledge as children of families that worked in agriculture. The many books they read about seeds growing into plants and their projects including growing plants and keeping a plant journal all expanded on what her students did know and gave them academic concepts and language. Their identities were validated as they learned. Another project that Sandra used with her students resulted in a transformation for them. The project involved both students and parents. Sandra's students were from Mexico, but Sandra was an immigrant from Argentina. She told her students she did not know how to make tortillas. They were incredulous and asked if they could show her how. Sandra bought materials as directed and the mothers brought in a tortilla press, a mortar and pestle, and even corn kernels and lime to show how corn is pro- cessed and ground into flour and made into tortillas. The students impressed Sandra as they set up two long tables and explained and demonstrated how corn is ground into corn flour and eventually is made into tortillas. This presentation by the students was so impressive that other teachers wanted them to repeat it for their classes. Sandra worked with her students to help them describe the process in English as they made their presentations. It was very empowering for these ESL students, who were usually left out and considered not important in the school. Through this activity they became sought-after presenters for the entire school. This experience gave the students confidence and was truly transformative. Taking an Advocacy Role in Assessment A fourth characteristic of schools that take an intercultural orientation is that they design assessments that allow all their students, including their English language learn- ers, to demonstrate what they have learned. Often, emergent bilinguals have learned much more than they can show on quizzes, tests, and essays written in English. However, they can show what they know when teachers use alternative forms of assessment, including assessment in their home language. When students make books, they show teachers they can organize their thoughts, and they understand how books are organized. They use language that is appropri- ate to talk about the pictures they choose, and they show vocabulary deve