Question

Q1. What are the advantages of an IPO rather than continuing with VC funding or entering a collaborative agreement with a major pharmaceutical company? Be

Q1. What are the advantages of an IPO rather than continuing with VC funding or entering a collaborative agreement with a major pharmaceutical company? Be specific to this case, not a general list. Be sure to address the advantages relative to VC and collaborative agreements.

Q2. Should ImmuLogic Pharmaceutical Corporation go public? Now or should it wait for 1 or 2 years?

Q3. What is the valuation of ImmuLogic in an IPO? Use the data in Table A7, and assume that the firm is planning to sell primary shares for $80m. Assume also that the yield on long term Government bonds is 7% and the risk premium on the market portfolio is 8%. Please see the accompanying excel sheet for additional tables on market comparables.

Q3 Current Event Alternative: What connections/comparisons can be made to IPOs of recent biotech firms? Through a mini-case of one firm or evidence of systemic shift/similarities across early funding of biotechs generally

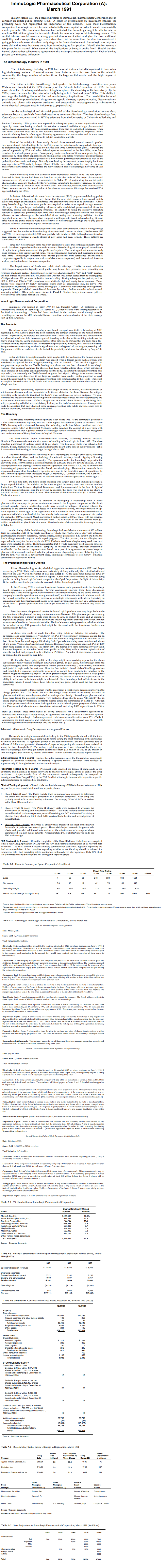

ImmuLogic Pharmaceutical Corporation (A): March 1991 In early March 1991, the board of directors of ImmuLogic Pharmaceutical Corporation met to consider an initial public offering (IPO). A series of presentations by investment bankers the preceding week had highlighted the importance of this decision. Like most biotechnology companies, ImmuLogic needed to raise substantially more capital in order to create commercially viable products. The investment bankers had indicated that ImmuLogic might be able to raise as much as $80 million, given the favorable climate for new offerings of biotechnology shares. This capital infusion would assure a strong product development effort and give the firm additional credibility and a competitive edge over a rival firm. At the same time, the directors wondered if going public made sense at such an early stage in the firm's development: ImmuLogic was only four years old and at least four years away from introducing its first product. Would the firm receive a fair price for its shares? What were all the implications of being a public firm? Should the firm instead sign another collaborative agreement with a major pharmaceutical company? Each of the key players saw the issues differently. The Biotechnology Industry in 1991 The biotechnology industry in 1991 had several features that distinguished it from other high-technology sectors. Foremost among these features were its close links to the scientific community, the large number of active firms, its large capital needs, and the high degree of uncertainty. The initial scientific breakthrough that sparked the biotechnology revolution was James Watson and Francis Crick's 1953 discovery of the "double helix" structure of DNA, the basic molecule of life. In subsequent decades, biologists explored the chemistry of life intensively. By the 1970s, researchers reached the point of actually being able to "cut and paste" DNA. This ability to rearrange the building blocks of life had revolutionary implications. The possibilities included production of computer-designed drugs to cure age-old diseases; super-productive, disease-resistant animals and plants with superior attributes; and custom-built microorganisms as substitutes for many chemical processes used in industry (e.g., papermaking). As the technological and financial potential of the biotechnology revolution became clear, scientists began to establish firms dedicated to its commercialization. The first biotechnology firm, Cetus Corporation, was started in 1971 by scientists from the University of California at Berkeley and Stanford University. This pattern was repeated in subsequent years, as new organizations were begun by researchers leaving academic laboratories or research facilities at large pharmaceutical firms, often in conjunction with nontechnical managers from new or established companies. These new firms cultivated close ties to the academic community. They typically employed formal scientific advisory boards, often signed licensing agreements with universities, and in some cases even encouraged researchers to continue to publish in scientific journals. Most of the activity in these newly formed firms centered around research, product development, and clinical testing. In the first 15 years of the industry, only two products developed by biotechnology firms were approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Although the pace of approvals by FDA and other federal agencies accelerated in the late 1980s, most firms remained in a development phase. Consequently, major emphases of firms were protecting their discoveries by filing patent applications and raising capital long before revenues or profits appeared. Table 1 summarizes the approval process for a new human pharmaceutical product as well as the probability of success in each stage. Not only was the drug development process lengthy but it was very expensive: a 1991 study by Joseph DiMasi of Tufts University's Center for Drug Development and several other authors had estimated the fully expensed cost of developing a new drug at $231 million. Many of the early firms had claimed in their promotional material to be "the next Syntex." Founded in 1946, Syntex had been the last firm to join the ranks of the major pharmaceutical manufacturers. (Syntex's history is summarized in Table 2.) A major drug for an integrated pharmaceutical company (such as Syntex's Naprosyn, SmithKline Beecham's Tagament, or Glaxo's Zantac) could yield $1 billion or more in annual sales. Not all drugs, however, were that successful. Chart 1 summarizes the discounted value of the after-tax revenues for 100 drugs that received FDA approval during the 1970s. In the face of the setbacks in research and development (R&D) programs and the long path to regulatory approval, however, the early dream that the new biotechnology firms would rapidly evolve into major pharmaceutical companies was gradually understood to be unrealistic. Almost every biotechnology firm that went public was required to raise more capital through seasoned offerings. Start-ups began undertaking alliances with established pharmaceutical firms for marketing, testing, and manufacturing products. In addition to using the extensive marketing network of established pharmaceutical firms, new biotechnology companies entered into strategic alliances to take advantage of the established firms' testing and screening facilities. Another important factor was the pharmaceutical companies' willingness to invest in biotechnology firms at times when the public markets were not receptive to biotechnology offerings and to pay greater prices in reflection of the rights implicit in deal structures. While a shakeout of biotechnology firms had often been predicted, Ernst & Young surveys suggested that the number of biotechnology firms remained constant at about 1,100 between 1987 and 1991. Of these, approximately 200 were publicly held in March 1991. Although many firms had been acquired or merged, a steady stream of new firms had been formed. These patterns are summarized in Chart 2 Since few biotechnology firms had been profitable to date, this continued industry activity would have been impossible without outside investors. Biotechnology firms employed several forms of capital from private sources and the public marketplace. The most significant source for early stage companies was venture capital funds, which specialized in financing and overseeing privately held firms. Increasingly important were private placements from established pharmaceutical companies (typically in conjunction with a collaborative arrangement) and institutional investors such as pension funds and insurance companies. The largest source of funds was public stock offerings. Unlike in most industries, biotechnology companies typically went public long before their products were generating any revenues, much less profits. Biotechnology stocks were characterized by "hot" and "cold" periods. The first of these followed the IPO of Genentech in October 1980, which soared from its offering price of $35 per share to $89 per share in the first hour of trading. During subsequent hot periods, such as 1982 to 1983 and 1986 to 1987, valuations were relatively high and equity issues common. These periods were triggered by highly publicized events such as acquisitions (e.g., Eli Lilly's 1986 acquisition of Hybritech), successful public offerings (i.e., Genentech's 1980 offering), and regulatory approvals. These periods had been followed, however, by a sharp decline in market valuations and in offering activity. (These patterns are shown in Chart 3. Similar, though less extreme, patterns were observed in the stock market as a whole.) ImmuLogic Pharmaceutical Corporation ImmuLogic was formed in early 1987 by Dr. Malcolm Gefter. A professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) since 1977, Gefter was one of the leading researchers in the field of immunology. Gefter had been involved in the business world through outside consulting, service on the MIT industrial liaison committee, and as a director of the biotechnology start-up firm Angenics. The Products The science upon which ImmuLogic was based emerged from Gefter's laboratory at MIT. Beginning in 1980, Gefter's group had been exploring the complex workings of the human immune system. In particular, he explored the question of how T-cells the white blood cells that identified and directed attacks on infections-recognized invading molecules while avoiding attacks on the body's own products. Along with researchers at other schools, he showed that the body had a fail- safe mechanism to prevent mistakes. No matter how provoked by invaders, the T-cells did not attack foreign molecules unless they received a signal from a second type of cell, an antigen-presenting cell. The presence of this second class of cells limited the possibility of destructive attacks by "rogue" T- cells. Gefter identified two applications for these insights into the workings of the human immune system. The first was allergies. An allergy was caused when a foreign agent, such as pollen, was mistakenly recognized by the antigen-presenting cells as harmful. This mistake triggered an inappropriate response by the T-cells, leading to a chain reaction that culminated in an allergic reaction. The standard treatment for allergies had been repeated allergy shots, which introduced small amounts of the allergy-causing substance into the body. Each time the antigen-presenting cells responded, but eventually the T-cells learned to ignore their signal. Allergy shots were expensive, time-consuming, and dangerous if too large an injection were made. Gefter proposed to inject instead the compound by which the antigen-presenting cells communicated to the T-cells. This could accomplish the reeducation of the T-cells with many fewer treatments and without the danger of an allergic reaction. The second opportunity, expected to take longer to come to fruition, was the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes. In these diseases, the antigen- presenting cells mistakenly identified the body's own substances as foreign antigens. To date, therapies had focused on either addressing only the consequences of these attacks or suppressing the body's entire immune system. Gefter's insight was to address these diseases by disabling those antigen-presenting cells that were mistakenly looking for the body's own substances. If compounds could be identified that only disabled those antigen-presenting cells while allowing other cells to continue their work, these diseases would be cured. The Company The first steps in forming ImmuLogic were taken in late 1986. As the commercial potential of Gefter's research became apparent, MIT and Gefter applied for a series of patents on his work. While MIT's licensing office discussed licensing the technology with Jess Belser, president and chief executive officer (CEO) of Rothschild Ventures, Gefter broached the concept of a new firm with James Bochnowski, then a general partner at Technology Venture Investors. Bochnowski brought the deal to the attention of Henry McCance of Greylock Ventures. The three venture capital firms--Rothschild Ventures, Technology Venture Investors, Greylock Ventures--undertook the first round of funding of ImmuLogic in June 1987. The three investors purchased 1.7 million shares at $2 per share. The firm as a whole was valued at $5.5 million. Belser, Bochnowski, and McCance all joined the board at the time of the investment. Table 3 summarizes the financing of ImmuLogic through March 1991. The firm addressed several key issues in 1987, including the leasing of office space, the hiring of a chief financial officer, and the building of a scientific advisory board. Signing a licensing agreement with MIT was another necessity. The agreement called for ImmuLogic to provide the university with 185,000 shares, a deferred payment of $750,000, and a 5% royalty on sales. A final accomplishment was signing a contract research agreement with Merck & Co., Inc. to enhance the immunological properties of a vaccine that Merck was developing. These contract research funds represented almost all of ImmuLogic's operating revenues in the firm's first years of operations. In 1988, ImmuLogic joined with Professors Hugh O. McDevitt, C. Garrison Fathman, and Kenneth L. Melmon of Stanford University, who had all realized a similar scientific approach to ImmuLogic's. By mid-June 1988, the firm's initial financing was largely gone, and ImmuLogic sought a larger capital infusion. In addition to the three original investors, four new venture funds- Institutional Venture Partners, Mayfield, Bessemmer, and Sprout-invested in the firm. In light of the firm's accomplishments over the previous 12 months, the price was fixed at $6 per share, a threefold increase over the original price. The valuation of the firm climbed to $31.4 million. (See Table 3 for terms.) Management next shifted its attention to developing a relationship with a major pharmaceutical company to pursue autoimmune research, the long-run component of the firm's research agenda. Such a relationship would have several advantages: it would enhance the credibility of the start-up firm, bring access to major research facility, and might include an up- front payment to ImmuLogic. After negotiations with a number of firms, ImmuLogic entered into an agreement with Merck, with which the firm already had a contract research arrangement. As part of the September 1989 agreement, Merck purchased 1 million shares at $10 per share, with the previous investors purchasing 200,000 shares between them. The valuation of the firm climbed from $31 million to $65 million. (See Table 3 for terms. The distribution of shares after this financing is shown in Table 4.) At the closing of this third financing, ImmuLogic had a cash balance in excess of $20 million. With an expanded staff of 72, nearly one-third of which had Ph.Ds., and a CEO with extensive pharmaceutical industry experience, Richard Bagley, former president of E.R. Squibb and Sons, the firm's allergy research program made rapid progress. The first product, for cat allergies, was expected to be ready for the marketplace in 1995. Products to address allergies to ragweed, dust, and grass were expected to follow. The firm anticipated that it would eventually need a second strategic alliance with a major pharmaceutical company to market its allergy products successfully worldwide. In the interim, payments from Merck as a part of its agreement to pursue long-run pharmaceutical research continued to be the primary source of operating revenue. Reflecting the fact that the firm was still in a development stage, ImmuLogic continued to lose money. Financial statements are reported in Table 5. The Proposed Initial Public Offering Prices of biotechnology stocks, which had lagged the market ever since the 1987 crash, began recovering in 1990. Their performance was particularly striking in the rally that coincided with and followed the Gulf War in the winter of 1991 (see Chart 4). At the same time, filings for IPOs by biotechnology firms increased, as Table 6 depicts. Other firms were rumored to consider going public, including ImmuLogic's closest competitor, the Cytel Corporation. In light of this activity, Gefter and his investors began seriously to consider taking ImmuLogic public. In late February 1991, a series of investment bankers made presentations to the ImmuLogic board concerning a public offering. Several conclusions emerged from these discussions. ImmuLogic, it was widely agreed, would be seen as an attractive offering by the public market. The company's scientific specialization, strong research staff, and influential scientific advisors would all be viewed favorably, as would the presence of a strategic relationship with Merck (especially in conjunction with the pharmaceutical giant's large equity investment in the start-up). Although none of the firm's 11 patent applications had been as yet awarded, the firm was confident they would be shortly. Most important, the potential market for ImmuLogic's products was very large, both in the medium term (allergies) and the long run (autoimmune diseases). Allergies were pervasive among the U.S. population: 5 million people were allergic to cats, 15 million to dust, and 25 million to ragweed and grasses. Some 1 million people were insulin-dependent diabetics, while over 2 million Americans suffered from rheumatoid arthritis. The firm's internal sales projections, which would not be included in any IPO prospectus but might be discussed with the investment bankers, are summarized in Table 7. A strong case could be made for either going public or delaying the offering. The appearance and disappearance of "windows" for IPOs by biotechnology companies argued for an immediate offering. The market was "hot" now, but there was no guarantee this condition would last. Some firms that tried to go public during "cold" periods found they were unable to sell shares at any price: Verax, MicroGeneSys, and Immune Response Corporation had canceled IPOs in 1989 after being unable to sell shares. (In March 1991, the former two firms remained privately held. Immune Response, on the other hand, went public in May 1990, with a market capitalization of roughly one-half that proposed in its withdrawn IPO filing. An index of biotechnology stocks had appreciated in the interim by over 25%.) On the other hand, going public at this stage might mean receiving a price for the shares substantially below what an offering in 1992 would garner. In past years, biotechnology firms had typically not gone public until their products were in preliminary (Phase I) human trials, which were anticipated to begin early the next year. Once the firm initiated clinical trials of its allergy vaccines and established a corporate partnership agreement to market these products, its valuation by the market might be substantially higher. An even greater concern was the possibility of a failed public offering. If ImmuLogic were unable to sell its shares, the impact on the firm's reputation and its ability to sell shares in the future might be substantial. Since ImmuLogic had sufficient cash for the immediate future, it could reduce these risks by delaying going public until the firm was more established. Lending weight to this argument was the prospect of a collaborative agreement involving the allergy product line. The board felt that the allergy drugs would be extremely attractive to pharmaceutical firms, since they comprised an entire product family. Several major pharmaceutical firms were facing the prospect of having very profitable drugs shortly going "off patent," that is, losing their monopoly protection as patents expired (these are summarized in Table 8). Although the major pharmaceutical companies had significant product development programs of their own- the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association estimated total drug R&D expenditures in 1990 about $8.1 billion-these firms would be strong candidates for a collaborative agreement to commercialize Immulogic's allergy drugs, an agreement that might involve a substantial up-front cash payment to ImmuLogic. Such an agreement could serve as an alternative to an IPO. (Table 9 summarizes the joint ventures and collaborative research agreements entered into by new U.S. biotechnology firms between September 1990 and March 1991.) Table A-1 Milestones in Drug Development and Approval Process The search for a single commercializable drug in the 1980s typically started with the trial- and-error screening of some 10,000 compounds before testing the most promising of the substances in animals and humans. A significant portion of the total investment-one that consumed tens of millions of dollars and generated thousands of pages of supporting documentation-consisted of taking the drug through the FDA's exacting regulatory process. It was estimated that the average cost of developing a new drug (in current dollars) rose from $1.3 million in 1960 to $50 million in 1979 and topped $230 million by the end of the 1980s. A brief outline of the process appears below. Initial screening (1 to 2 years) During the initial screening stage, the thousands of compounds regarded as potential candidates for treating a specific medical condition were reduced to approximately 20 through chemical and structural analysis. Preclinical Testing (2 to 3 years) Preclinical trials involved the testing of compounds in the laboratory and in animals to assess safety and to analyze the biological effects of each of the drug candidates. Approximately five of the compounds would subsequently be accepted as Investigational New Drugs (INDS) by the FDA for clinical testing in humans with respect to a specific indication (disease or other medical condition). Clinical Testing (6 years) Clinical trials involved the testing of INDs in human volunteers. This stage of the process was divided into three separate phases: Phase I Trials (1 year) The Phase I safety trials in humans were designed to determine the safety and pharmacological properties of a chemical compound. Each drug was typically tested in 20 or more healthy volunteers. On average, 70% of all INDs moved on to the Phase II human trials. Phase II Trials (2 years) The Phase II efficacy trials were designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the drug and to isolate side effects. Tests were typically conducted with several hundred (volunteer) patients, one-half receiving the IND and one-half receiving a placebo. Only about one-third of all INDs survived both the first and second phases of clinical testing. Phase III Trials (3 years) The Phase III efficacy trials measured the effect of the IND on thousands of patients over several years. These trials helped ascertain long-term side effects and provided additional information on the effectiveness of a range of doses administered to a rich mix of patients. Approximately 27% of all INDs moved on to the FDA review stage. FDA Review (2 to 3 years) Upon the completion of the Phase III clinical trials, firms were required to file a New Drug Application (NDA) with the FDA and submit documentation of all relevant data for review. The FDA created a special advisory committee for each NDA, typically approving the final recommendation of the committee regarding whether or not the drug should be released for commercial sale. Post-marketing safety monitoring continued even after approval. Only 20% of all INDs ultimately made it through the full testing and approval stages. Table A-2 Financial Summary of Syntex Corporation' ($ millions) Fiscal Year Ending 7/31/60 7/31/65 7/31/70 7/31/75 7/31/80 7/31/85 7/31/90 3/15/91 Sales 7 36 90 246 580 949 1521 Net income 0.3 10 12 42 75 150 342 Operating margin 3% 26% 14% 17% 19% 23% 30% Market capitalization (at fiscal year end) 43 408 256 681 716 1994 6911 8513 Source: Compiled from Moody's Industrial Guide, various years; Daily Stock Price Guide, various years; Value Line Guide, various years. "Syntex went public through a rights offering to the shareholders of the Ogden Corporation in April 1958. Ogden had acquired the assets of Syntex's predecessor firm, which had been a development stage firm throughout most of the 1950s. "Syntex's initial market capitalization in 1958 was approximately $10 million. Table A-3 Financing of ImmuLogic Pharmaceutical Corporation, 1987 to March 1991 Date: May 21, 1987. Series A Convertible Preferred Stock Agreement Shares Sold: 1,675,000, at $2.00 per share. Total Valuation: $5.5 million. Dividends: Series A shareholders are entitled to receive a dividend of $0.20 per share, beginning on June 1, 1990, if declared by the Board. This dividend is non-cumulative. No dividend can be paid to holders of common stock until the Series A dividend for the fiscal year is paid. Holders of Series A stock must obtain the share of any dividends paid to the common stock equivalent to the amount they would have received had they converted all their shares to common stock. Liquidation: If the company is liquidated, the company will pay $2.00 for each share of Series A stock, plus any dividends declared but unpaid, before any payments are made to the common stockholders. The remaining amount will be then split equally between the Series A and common shareholders. If the net assets of the company after liquidation are insufficient to pay $2.00 per share of Series A stock, the net assets of the company will be split among the preferred shareholders. Conversion: Each Series A share is convertible into one share f common stock. If the company goes public at a price exceeding $10.00 per share (adjusted for any stock splits) in an offering which raises at least $10 million dollars, the Series A shares will be automatically converted into common stock. Voting Rights: Each Series A share is entitled to one vote in any matter submitted to the vote of the shareholders. Holders of three-quarters of the Series A shares must authorize the issue of any shares which are senior or equal to the Series A in dividend or liquidation rights. Holders of three-quarters of the Series A shares must also approve any merger, liquidation or sale of the firm or an increase in the number of the directors of the firm beyond five. Board Seats: Series A shareholders are entitled to elect four directors of the company. The Board will meet at least six times a year. Each owner of 450,000 shares can send an observer to the meetings. Redemption: The company must liquidate one-third of the Series A shares outstanding on December 31, 1995, one- half of those outstanding on December 31, 1996, and all remaining shares on December 31, 1997. In each case, the holders of liquidated Series A shares will receive a payment of $2.00. The redemption can only be waived on the vote of two-thirds of the Series A shareholders. Registration Rights: Series A shareholders can demand that the company include their shares in any registration statement for the public sale of stock that the company files. Series A shareholders can also demand that the company register their securities after December 31, 1992. In the former case, the Series A shareholders will bear their share of the cost of the offering; in the latter case, the company shall bear the full expense of filing the registration statement, legal and accounting fees and other underwriting costs. Preemptive Rights: Series shareholders have the right to purchase any class of shares, bonds, options or other securities that the company proposes to sell. This does not includes shares sold to the company's employee benefit plan. Covenants and Adjustments: The company agrees to pay all taxes and fees, keep accurate accounting records, and other covenants. All restrictions will be adjusted for any stock splits. Series B Convertible Preferred Stock Agreement [Modifications Only] Date: July 11, 1988. Shares Sold: 2,129,167, at $6.00 per share. Total Valuation: $31.4 million. Dividends: Series B shareholders are entitled to receive a dividend $0.45 per share, beginning on June 1, 1993, if declared by the Board as above. [Series A dividends are changed to $0.15 per share, also beginning on June 1, 1993.] Neither Series A and Series B shareholders can receive dividends without the other. Liquidation: If the company is liquidated, the company will pay $2.00 for each share of Series A stock and $6.00 for each share of Series B stock as above. The maximum additional payout to Series A and B shareholders is capped at $6.00 per share. Conversion: Each Series B share is initially convertible into one share of common stock. This conversion ratio may be adjusted upward if the company issues additional shares of common stock. If the company goes public at a price exceeding $15.00 per share in an offering which raises at least $10 million dollars, the Series B shares will be automatically converted into common stock. [The automatic conversion price of Series A shares is similarly adjusted.] Voting Rights: Each Series B share is entitled to one vote in any matter submitted to the vote of the shareholders. Holders of two-thirds of the Series B shares must authorize the issue of any shares which are senior or equal to the Series B in dividend or liquidation rights. [The required majority for Series A shareholders is similarly changed to two- thirds.] Holders of two-thirds of the Series A and B shares must jointly approve any merger, liquidation or sale of the firm. Board Seats and Redemption: [Board seat and redemption provisions for Series A shares canceled.] Registration Rights: Series A and B shareholders can demand that the company include their shares in any registration statement for the public sale of stock that the company files. 30% of all Series A and B shareholders (as converted) can also demand that the company register their securities after December 31, 1992, providing the offering price of their equity will exceed $10 million. [Additional registration rights of Series A shareholders canceled.] Underwriting costs as above. Series C Convertible Preferred Stock Agreement [Modifications Only] Date: October 4, 1989. Shares Sold: 1,200,000, at $10.00 per share. Total Valuation: $63.3 million. Dividends: Series C shareholders are entitled to receive a dividend $0.75 per share, beginning on June 1, 1993, if declared by the Board as above. Liquidation: If the company is liquidated, the company will pay $2.00 for each share of Series A stock, $6.00 for each share of Series B stock, and $10.00 for each share of Series C stock as above. Conversion: Each Series C share is initially convertible into one share of common stock. This conversion ratio may be adjusted upward if the company issues additional shares of common stock. If the company goes public at a price $15.00 per share in an offering which raises at least $10 million dollars, the Series C shares will be automatically converted into common stock. exceeding Voting Rights: Each Series C share is entitled to one vote in any matter submitted to the vote of the shareholders. Holders of two-thirds of the Series C shares must authorize the issue of any shares which are senior or equal to the Series C in dividend or liquidation rights. Holders of two-thirds of the Series A, B and C shares must jointly approve any merger, liquidation or sale of the firm. Registration Rights: Series A, B and C shareholders can demand registration as above. Table A-4 5% Shareholders of ImmuLogic Pharmaceutical Corporation Shares Beneficially Owned Number 1,150,000 Percent 17.9% 14.6 Name Merck & Co., Inc. Arrow Partners (Rothschild, Inc.) Greylock Partnerships Technology Venture Investors Institutional Venture Partners Mayfield Funds Malcolm L. Gefter Other officers and directors Other venture funds, consultants and employees Source: Corporate documents 941,451 705,732 11.0 628,333 9.8 557,663 8.7 371,437 5.8 500,000 7.8 314,125 4.6 1,267,024 19.8 A-5 Financial Statements of ImmuLogic Pharmaceutical Corporation: Balance Sheets, 1988 to Table 1990 ($ 000s) Sponsored research revenues Operating expenses: Research and development General and administrative Total expenses Operating loss Interest income, net Net loss 1988 1989 1990 $ 1,426 $ 3,230 $ 3,265 2,721 5,181 7,236 1,982 2,227 3.367 4,702 7,409 10,602 (3,276) (4,179) (7,337) 565 1,034 $(2.711) $(3.145) 1,294 $(6,043) Table A-5 (continued) Consolidated Balance Sheets, December 31, 1989 and 1990 ($000s) ASSETS Current assets: Cash and cash equivalents Prepaid expenses and other current assets Interest receivable Total current assets Property and equipment, net Other assets Total assets LIABILITIES Current liabilities: Accounts payable Accrued expenses Note payable Current portion of capital lease Total current liabilities Other noncurrent liabilities Capital lease obligation Total liabilities STOCKHOLDERS' EQUITY Convertible preferred stock: Series A, $.01 par value; 1,675,000 shares authorized; 1,675,000 shares 12/31/89 12/31/90 $20,084 $14,786 199 258 183 98 20,466 15,142 3,461 3,266 201 195 $24.128 $18.604 $ 271 $ 282 239 363 150 218 245 877 890 750 1,105 859 1,982 2,499 issued and outstanding at December 31, 1989 and 1990 17 17 Series B, $.01 par value; 2,129,167 shares authorized, 2,129,167 shares issued and outstanding at December 31, 1989 and 1990 Series C, $.01 par value; 1,200,000 shares authorized, 1,200,000 shares issued and outstanding at December 31, 1989 and 1990 Common stock, $.01 par value; 8,100,000 shares authorized; 1,523,288 and 1,324,098 shares issued and outstanding at December 31, 1989 and 1990 Additional paid-in capital Less note receivable Accumulated deficit Total stockholder's equity Total liabilities and stockholders' equity Source: Corporate documents. 21 12 15 13 28,745 28,749 (81) (81) (6,584) (12,627) 22,146 16,104 $24,128 $18,604 Table A-6 Biotechnology Initial Public Offerings in Registration, March 1991 Shares % of Company Market Filing Filed Represented by Filing Capitalization Company Date (millions) These Shares Range ($0) ($ millions) Applied Immune Sciences, Inc. 3/22/91 2.3 33.8 10-12 75 Cephalon, Inc. 3/15/91 2.3 30.3 17-19 137 Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 2/20/91 3.0 21.6 16-19 243 Book Other Managing Other Issuer's Managing Legal Issuer's Manager Underwriter (1) Underwriter (2) Counsel Montgomery Securities Furman Selz Hambrecht & Quist Cowen & Co. Morgan, Lewis & Latham & Watkins Auditor Emst & Young Arthur Andersen Bockius Merrill Lynch Smith Barney S.G. Warburg Skadden, Arps Coopers & Lybrand Source: Corporate documents. aMarket capitalizations calculated using midpoint of filing range. Table A-7 Sales Projections for ImmuLogic Pharmaceutical Corporation, March 1991 ($ millions) 1994E 1995E 1996E 1997E 1998E AllerVax sales Cat 0.00 15.00 40.00 60.00 75.00 Ragweed 25.00 65.00 120.00 Mite 40.00 85.00 Grasses 20.00 Allervax royalties 1.50 6.50 16.50 30.00 Allergic rhinitis 20.00 20.00 Asthma Total 0.00 16.50 71.50 181.50 370.00

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Q1 Advantages of an IPO over VC funding and collaborative agreements 1 Control and autonomy An IPO allows ImmuLogic to maintain control and autonomy over its business operations whereas VC funding can ...

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started