Question 1 Criticallyanalyzethe statement petroleum industry is also highly capital-intensive, so strong returns are critical to attracting low-cost debt and equity capital. In fact, while

Question 1

Criticallyanalyzethe statement petroleum industry is also highly capital-intensive, so strong returns are critical to attracting low-cost debt and equity capital. In fact, while many of the integrated companies have the cash flow and financial wherewithal

to fund capital spending internally, they frequently rely on external debt and new equity

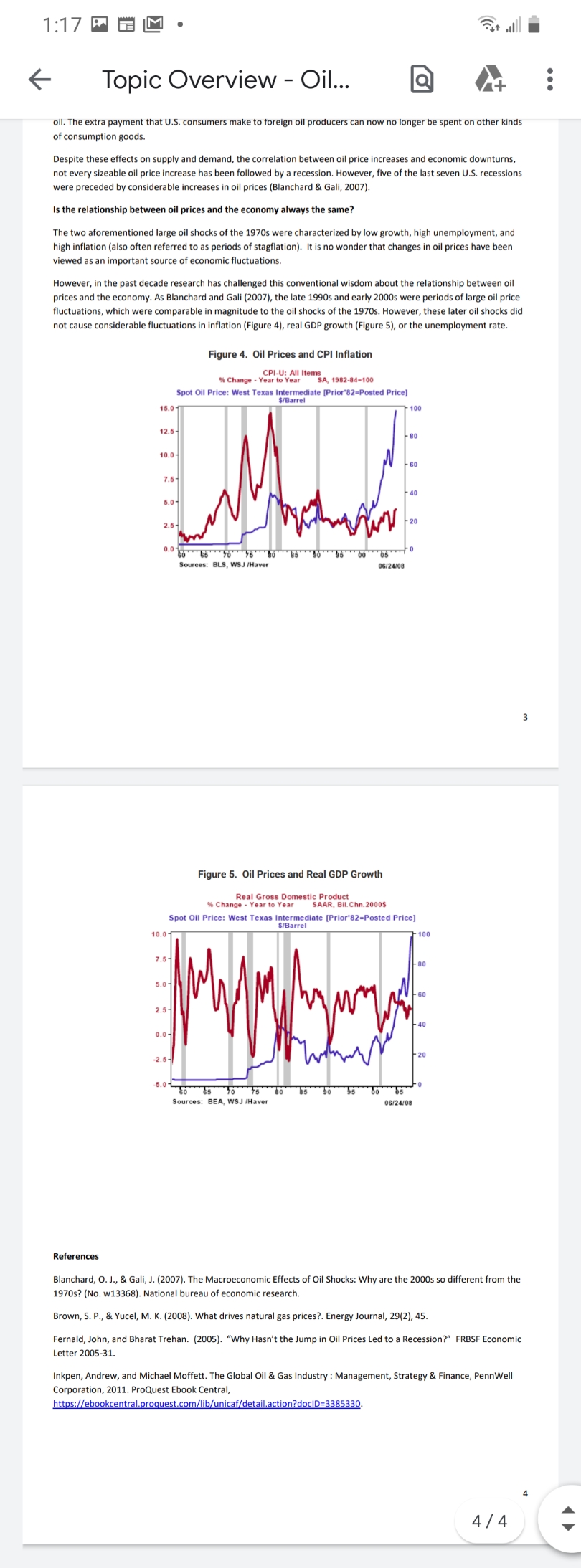

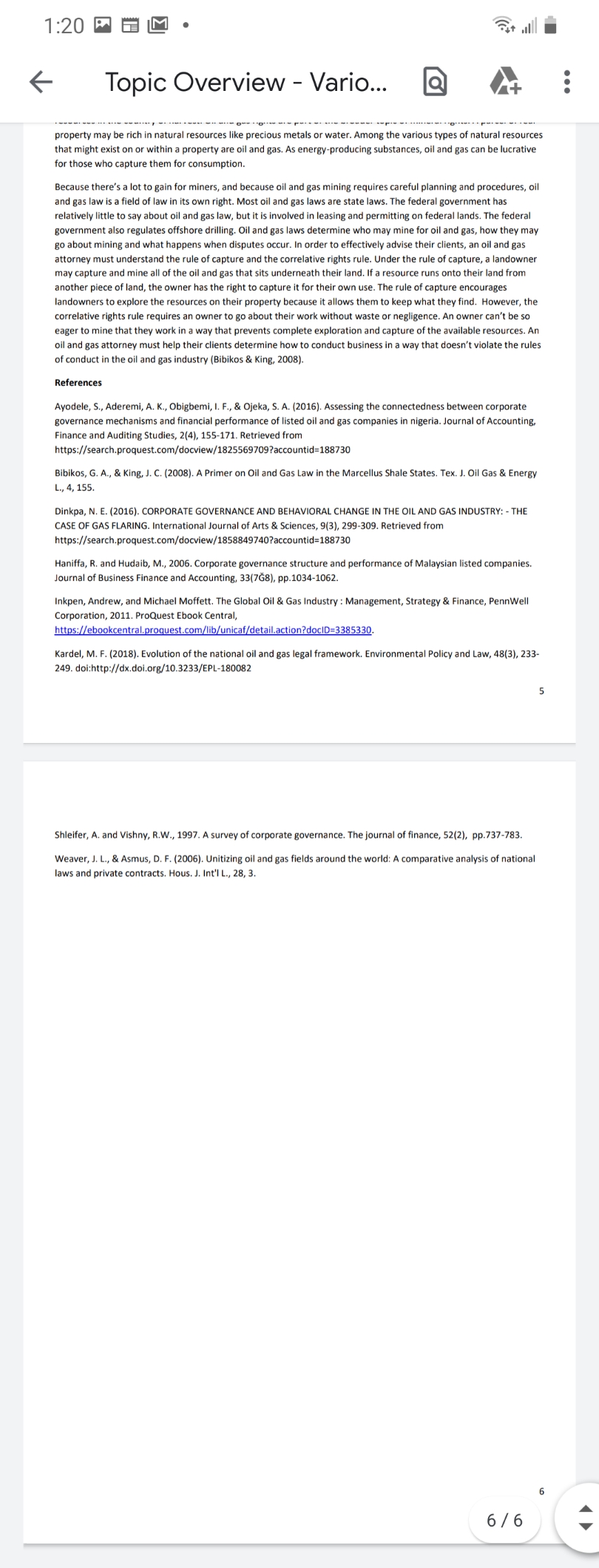

capital, particularly to finance larger acquisitions and mergers'.

support your paper with a minimum of seven (7) resources. In addition to these specified resources, other

appropriate scholarly resources, including older articles of your choice, may be included.

Length: 8 - 9 pages not including title and reference pages. Approximately 3000 - 3500

words. Your pages must be Double spaced with a Font style Times New Roman and 12

Font Size.

Your paper should reflect scholarly writing and APA Referencing standard. Be sure to adhere to

Academic Integrity Policy by avoiding plagiarism through text-citing and acknowledging other

author's work.

Pls see attached material's

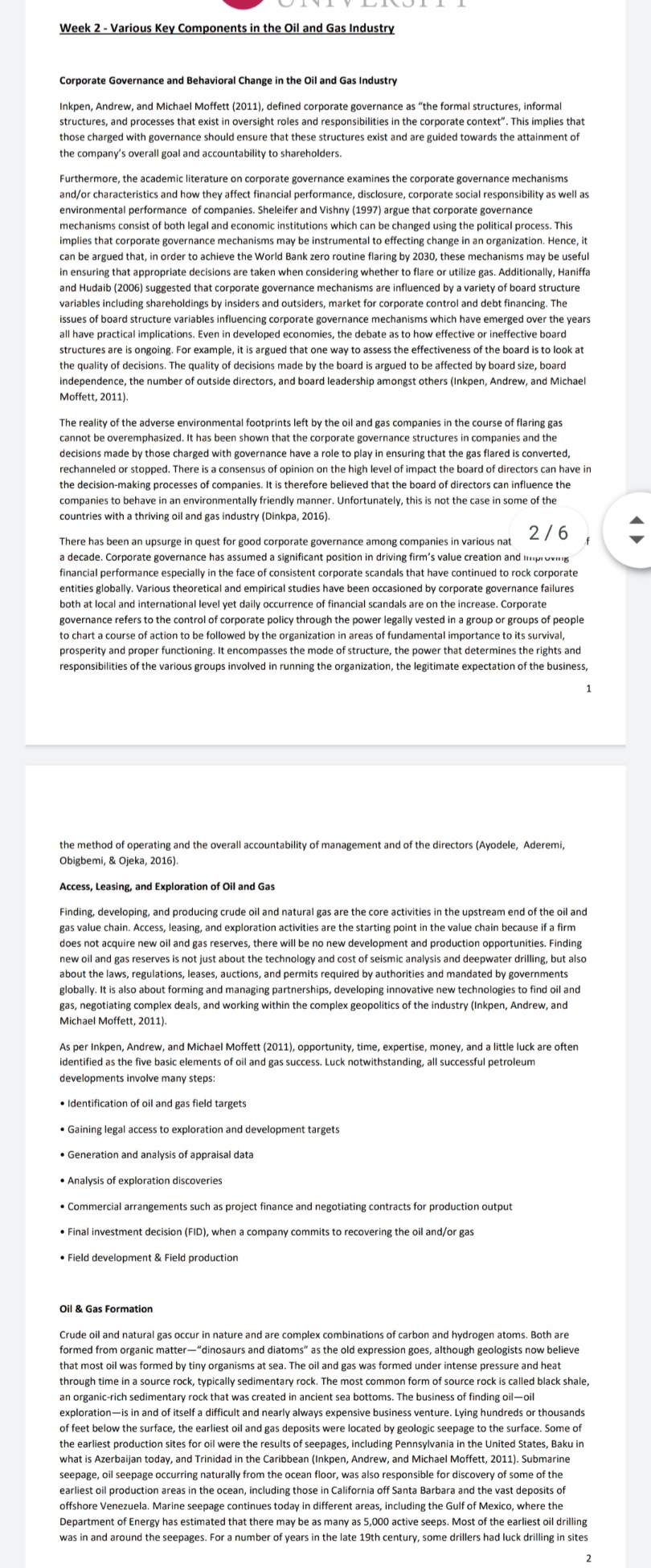

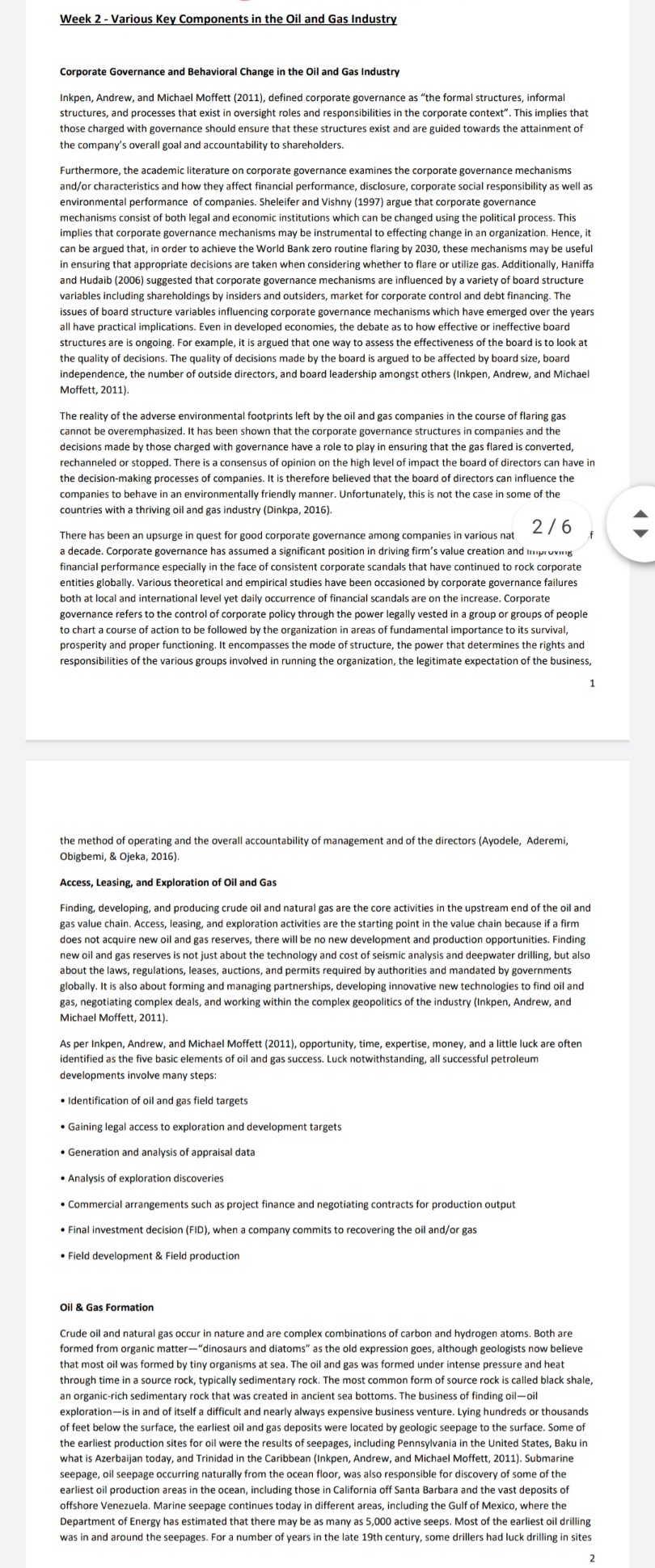

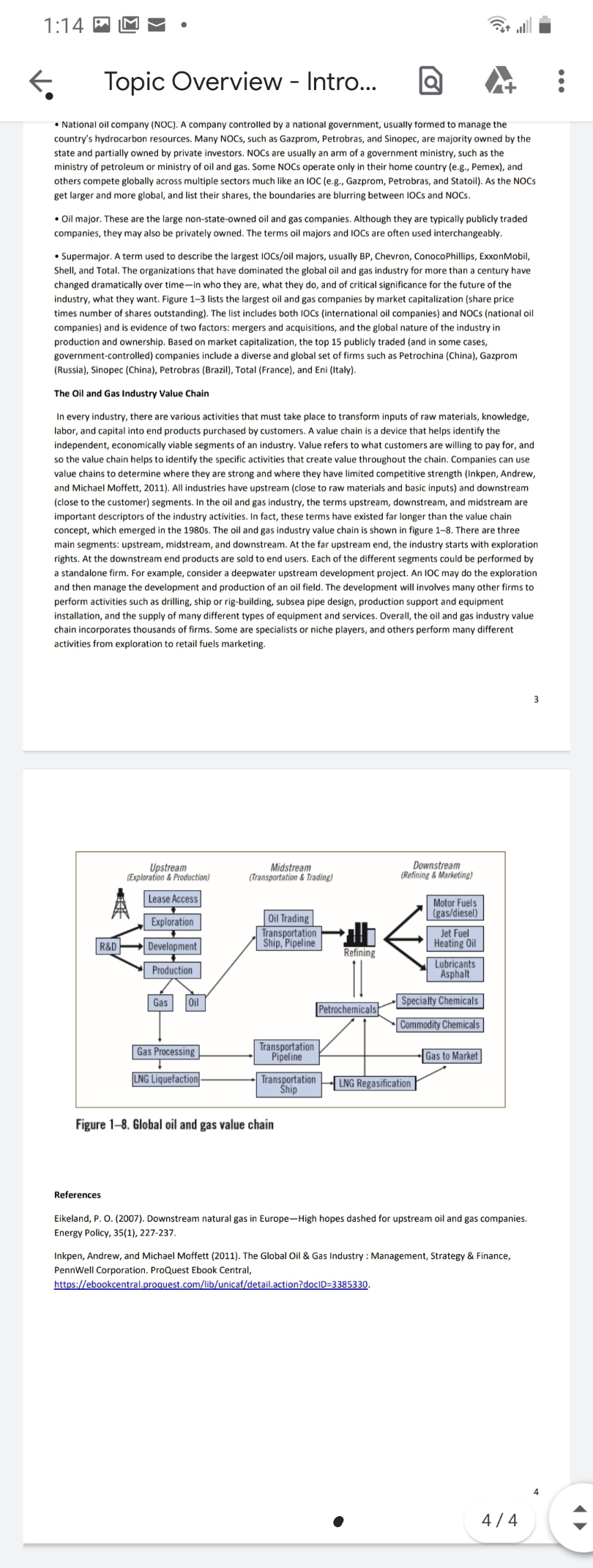

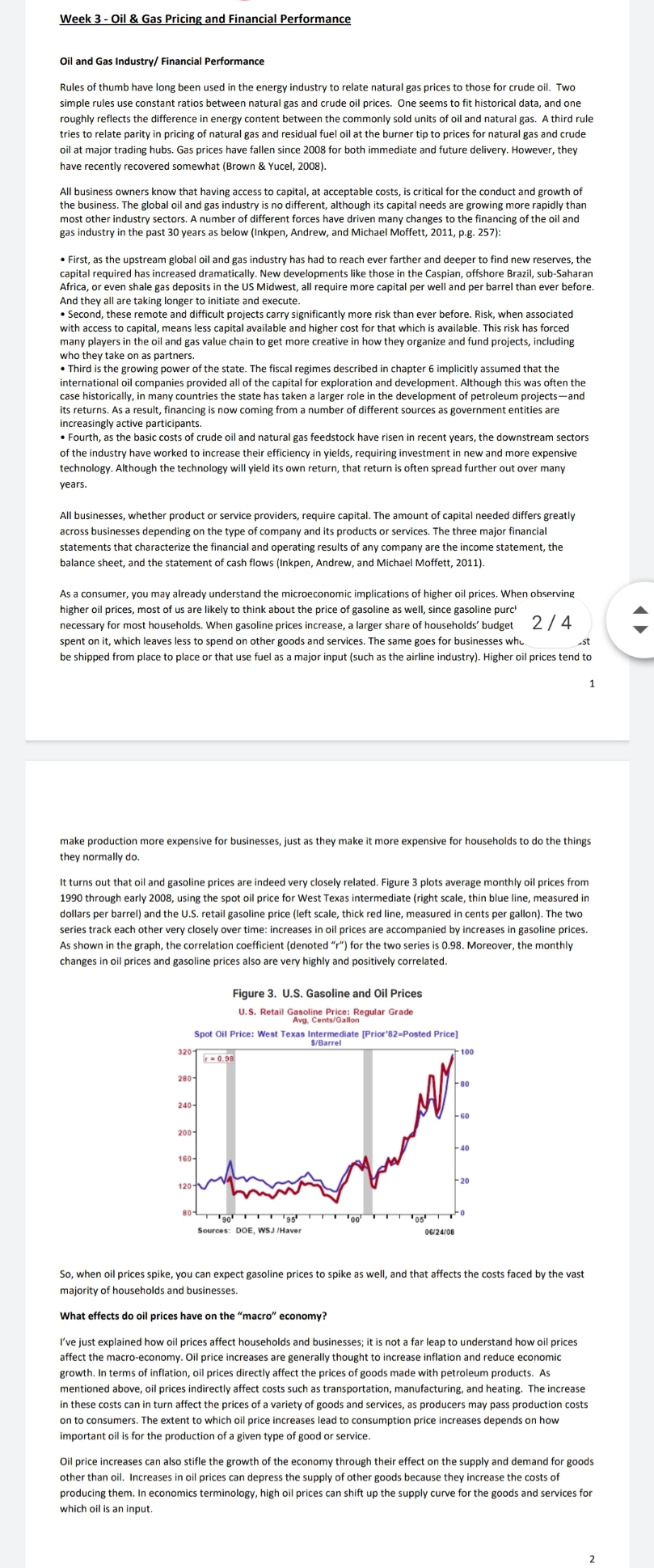

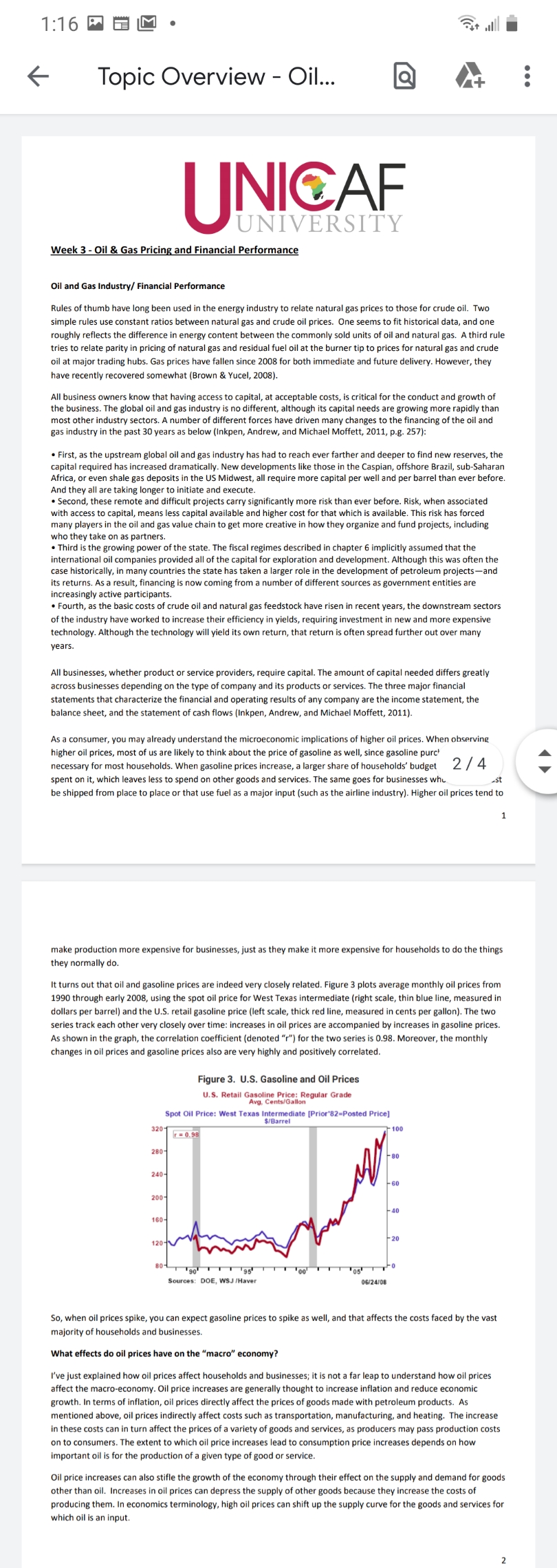

Week 1 - Introduction to Oil and Gas Industry Introduction to Oil and Gas Industry The oil and gas industry is one of the largest, most complex, and important global industries. The industry touches everyone's lives with products such as transportation, heating, and electricity fuels; asphalt; lubricants; propane; and thousands of petrochemical products from carpets to eyeglasses to clothing. The industry impacts national security, elections, geopolitics, and international conflicts. The prices of crude oil and natural gas are probably the two most closely watched commodity prices in the global economy (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). Since the beginning of the oil industry, petroleum producers and consumers have feared that eventually the oil would run out. In 1950, the US Geological Survey estimated that the world's conventional recoverable resource base was about 1 trillion barrels. Fifty years later, that estimate had tripled to 3 trillion barrels. In recent years, the concept of peak oil has been much debated. The peak oil theory is based on the fact that the amount of oil is finite. As per Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett (2011), discovering new oil and gas reserves is the lifeblood of the industry. Without new reserves to replace oil and gas production, the industry would die. However, measuring and valuing reserves is a scientific and business challenge because reserves can only be measured if they have value in the marketplace. The oil and gas industry employs hundreds of thousands of workers worldwide and generates billions of dollars globally each year. It is easy to say that this industry is a global powerhouse. As per Eikeland (2007), the industry is divided into three major stages: Upstream, midstream, and downstream. Upstream is also known as exploration and production stage and involves the search for underwater underground oil and gas deposits. The drilling of exploration wells is the main activity of this stage. 2/4 The second stage, midstream, refers to the collection and transportation of crude oil, natural gas, and refined products, usually via pipeline, oil tanker, barge, truck or rail. This stage also includes the storage of products as well as any wholesale marketing efforts (Eikeland, 2007). Downstream is the filtering of the raw materials obtained during the upstream phase. Long story short, this means refining crude oil and purifying natural gas. The products generated from this section of the process include natural gas, diesel oil, petrol, gasoline, lubricants, kerosene, jet fuel, asphalt, heating oil, LPG, just to name a few. While each stage is different, each plays a critical role in the overall process. Together all three stages help power the world (Eikeland, 2007). The oil and gas industry requires miles and miles of mechanical pipe insulation to maintain low thermal conductivity, reduce heat loss, and insulate against freezing temperatures. Low temperatures and high pressures can quickly form deposits that clog flowlines. Using industrial insulation is a cost-effective solution for maintaining temperature and flow rates, optimizing productivity, and reducing processing costs. The gas and oil industry has been extremely successful since the discovery of oil and will continue to experience growth in the years to come. As this industry continues to grow, the demand for reliable and durable insulation solutions has never been greater (Eikeland, 2007). Oil and Gas in the Global Economy. The Players Oil and gas play a vital role in the global economy. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that energy demand will rise by an average of 1.5% each year through 2030. Demand in 2030 will be about 60% higher than in 2000. Demand in the non-OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) nations will account for approximately 80% of the global increase. Most of the world's growing energy needs through 2030 will continue to be met by oil, gas, and coal. With increased energy efficiency, energy as a percentage of the total gross domestic product (GDP) has fallen and is expected to continue to fall. Oil and gas supply one of the fascinating aspects of the industry is the fact that all countries are consumers of products derived from the oil and gas industry, but only a small set of nations are major producers of oil and gas. Over the past decades, the large developed economies of the world have become net importers of oil and gas, giving rise to challenging geopolitical issues involving a diverse set of oil consumers and producers (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). The global oil and gas industry is made up of thousands of firms of all shapes, sizes, and capabilities. The industry may suffer from an overabundance of terminology when describing these players, so here is some clarification of names and identities (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011, p.g. 11-12): . Independent. A nonintegrated company generating nearly all its revenue from either oil and gas production or downstream activities. The term independent is sometimes used more narrowly to refer only to oil and gas producers and not downstream firms. . Integrated oil company (IOC). A company that competes in the upstream, midstream, downstream, and perhaps petrochemicals. IOC is a term usually used in reference to large oil and gas companies-BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, Shell, and Total-and could also include smaller firms such as Eni and Marathon. International oil company (IOC). An oil and gas company that competes across borders. More generally, the term is used to describe the largest oil and gas companies that compete globally and often operate in partnership with NOCs in the NOC's home country. Because most IOCs are involved in oil and gas, a more appropriate term would be international energy company. Confusingly, international oil companies and integrated oil companies both use theWeek 2 - Various Key Components in the Oil and Gas Industry Corporate Governance and Behavioral Change in the Oil and Gas Industry Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett (2011), defined corporate governance as "the formal structures, informal structures, and processes that exist in oversight roles and responsibilities in the corporate context". This implies that those charged with governance should ensure that these structures exist and are guided towards the attainment of the company's overall goal and accountability to shareholders. Furthermore, the academic literature on corporate governance examines the corporate governance mechanisms and/or characteristics and how they affect financial performance, disclosure, corporate social responsibility as well as environmental performance of companies. Sheleifer and Vishny (1997) argue that corporate governance mechanisms consist of both legal and economic institutions which can be changed using the political process. This implies that corporate governance mechanisms may be instrumental to effecting change in an organization. Hence, it can be argued that, in order to achieve the World Bank zero routine flaring by 2030, these mechanisms may be useful in ensuring that appropriate decisions are taken when considering whether to flare or utilize gas. Additionally, Haniffa and Hudaib (2006) suggested that corporate governance mechanisms are influenced by a variety of board structure variables including shareholdings by insiders and outsiders, market for corporate control and debt financing. The issues of board structure variables influencing corporate governance mechanisms which have emerged over the years all have practical implications. Even in developed economies, the debate as to how effective or ineffective board structures are is ongoing. For example, it is argued that one way to assess the effectiveness of the board is to look at the quality of decisions. The quality of decisions made by the board is argued to be affected by board size, board independence, the number of outside directors, and board leadership amongst others (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). The reality of the adverse environmental footprints left by the oil and gas companies in the course of flaring gas cannot be overemphasized. It has been shown that the corporate governance structures in companies and the decisions made by those charged with governance have a role to play in ensuring that the gas flared is converted, rechanneled or stopped. There is a consensus of opinion on the high level of impact the board of directors can have in the decision-making processes of companies. It is therefore believed that the board of directors can influence the companies to behave in an environmentally friendly manner. Unfortunately, this is not the case in some of the countries with a thriving oil and gas industry (Dinkpa, 2016). There has been an upsurge in quest for good corporate governance among companies in various nat 2/6 a decade. Corporate governance has assumed a significant position in driving firm's value creation and limp uvius financial performance especially in the face of consistent corporate scandals that have continued to rock corporate entities globally. Various theoretical and empirical studies have been occasioned by corporate governance failures both at local and international level yet daily occurrence of financial scandals are on the increase. Corporate governance refers to the control of corporate policy through the power legally vested in a group or groups of people to chart a course of action to be followed by the organization in areas of fundamental importance to its survival, prosperity and proper functioning. It encompasses the mode of structure, the power that determines the rights and responsibilities of the various groups involved in running the organization, the legitimate expectation of the business, the method of operating and the overall accountability of management and of the directors (Ayodele, Aderemi, Obigbemi, & Ojeka, 2016). Access, Leasing, and Exploration of Oil and Gas Finding, developing, and producing crude oil and natural gas are the core activities in the upstream end of the oil and gas value chain. Access, leasing, and exploration activities are the starting point in the value chain because if a firm does not acquire new oil and gas reserves, there will be no new development and production opportunities. Finding new oil and gas reserves is not just about the technology and cost of seismic analysis and deepwater drilling, but also about the laws, regulations, leases, auctions, and permits required by authorities and mandated by governments globally. It is also about forming and managing partnerships, developing innovative new technologies to find oil and gas, negotiating complex deals, and working within the complex geopolitics of the industry (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). As per Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett (2011), opportunity, time, expertise, money, and a little luck are often identified as the five basic elements of oil and gas success. Luck notwithstanding, all successful petroleum developments involve many steps: . Identification of oil and gas field targets . Gaining legal access to exploration and development targets Generation and analysis of appraisal data . Analysis of exploration discoveries . Commercial arrangements such as project finance and negotiating contracts for production output . Final investment decision (FID), when a company commits to recovering the oil and/or gas . Field development & Field production Oil & Gas Formation Crude oil and natural gas occur in nature and are complex combinations of carbon and hydrogen atoms. Both are formed from organic matter-"dinosaurs and diatoms" as the old expression goes, although geologists now believe that most oil was formed by tiny organisms at sea. The oil and gas was formed under intense pressure and heat through time in a source rock, typically sedimentary rock. The most common form of source rock is called black shale, an organic-rich sedimentary rock that was created in ancient sea bottoms. The business of finding oil-oil exploration-is in and of itself a difficult and nearly always expensive business venture. Lying hundreds or thousands of feet below the surface, the earliest oil and gas deposits were located by geologic seepage to the surface. Some of the earliest production sites for oil were the results of seepages, including Pennsylvania in the United States, Baku in what is Azerbaijan today, and Trinidad in the Caribbean (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). Submarine seepage, oil seepage occurring naturally from the ocean floor, was also responsible for discovery of some of the earliest oil production areas in the ocean, including those in California off Santa Barbara and the vast deposits of offshore Venezuela. Marine seepage continues today in different areas, including the Gulf of Mexico, where the Department of Energy has estimated that there may be as many as 5,000 active seeps. Most of the earliest oil drilling was in and around the seepages. For a number of years in the late 19th century, some drillers had luck drilling in sitesWeek 2 - Various Key Components in the Oil and Gas Industry Corporate Governance and Behavioral Change in the Oil and Gas Industry Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett (2011), defined corporate governance as "the formal structures, informal structures, and processes that exist in oversight roles and responsibilities in the corporate context". This implies that those charged with governance should ensure that these structures exist and are guided towards the attainment of the company's overall goal and accountability to shareholders. Furthermore, the academic literature on corporate governance examines the corporate governance mechanisms and/or characteristics and how they affect financial performance, disclosure, corporate social responsibility as well as environmental performance of companies. Sheleifer and Vishny (1997) argue that corporate governance mechanisms consist of both legal and economic institutions which can be changed using the political process. This implies that corporate governance mechanisms may be instrumental to effecting change in an organization. Hence, it can be argued that, in order to achieve the World Bank zero routine flaring by 2030, these mechanisms may be useful in ensuring that appropriate decisions are taken when considering whether to flare or utilize gas. Additionally, Haniffa and Hudaib (2006) suggested that corporate governance mechanisms are influenced by a variety of board structure variables including shareholdings by insiders and outsiders, market for corporate control and debt financing. The issues of board structure variables influencing corporate governance mechanisms which have emerged over the years all have practical implications. Even in developed economies, the debate as to how effective or ineffective board structures are is ongoing. For example, it is argued that one way to assess the effectiveness of the board is to look at the quality of decisions. The quality of decisions made by the board is argued to be affected by board size, board independence, the number of outside directors, and board leadership amongst others (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). The reality of the adverse environmental footprints left by the oil and gas companies in the course of flaring gas cannot be overemphasized. It has been shown that the corporate governance structures in companies and the decisions made by those charged with governance have a role to play in ensuring that the gas flared is converted, rechanneled or stopped. There is a consensus of opinion on the high level of impact the board of directors can have in the decision-making processes of companies. It is therefore believed that the board of directors can influence the companies to behave in an environmentally friendly manner. Unfortunately, this is not the case in some of the countries with a thriving oil and gas industry (Dinkpa, 2016). There has been an upsurge in quest for good corporate governance among companies in various nat 2/6 a decade. Corporate governance has assumed a significant position in driving firm's value creation and limp uving financial performance especially in the face of consistent corporate scandals that have continued to rock corporate entities globally. Various theoretical and empirical studies have been occasioned by corporate governance failures both at local and international level yet daily occurrence of financial scandals are on the increase. Corporate governance refers to the control of corporate policy through the power legally vested in a group or groups of people to chart a course of action to be followed by the organization in areas of fundamental importance to its survival, prosperity and proper functioning. It encompasses the mode of structure, the power that determines the rights and responsibilities of the various groups involved in running the organization, the legitimate expectation of the business, the method of operating and the overall accountability of management and of the directors (Ayodele, Aderemi, Obigbemi, & Ojeka, 2016). Access, Leasing, and Exploration of Oil and Gas Finding, developing, and producing crude oil and natural gas are the core activities in the upstream end of the oil and gas value chain. Access, leasing, and exploration activities are the starting point in the value chain because if a firm does not acquire new oil and gas reserves, there will be no new development and production opportunities. Finding new oil and gas reserves is not just about the technology and cost of seismic analysis and deepwater drilling, but also about the laws, regulations, leases, auctions, and permits required by authorities and mandated by governments globally. It is also about forming and managing partnerships, developing innovative new technologies to find oil and gas, negotiating complex deals, and working within the complex geopolitics of the industry (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011) As per Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett (2011), opportunity, time, expertise, money, and a little luck are often identified as the five basic elements of oil and gas success. Luck notwithstanding, all successful petroleum developments involve many steps: . Identification of oil and gas field targets . Gaining legal access to exploration and development targets Generation and analysis of appraisal data . Analysis of exploration discoveries Commercial arrangements such as project finance and negotiating contracts for production output . Final investment decision (FID), when a company commits to recovering the oil and/or gas Field development & Field production Oil & Gas Formation Crude oil and natural gas occur in nature and are complex combinations of carbon and hydrogen atoms. Both are formed from organic matter-"dinosaurs and diatoms" as the old expression goes, although geologists now believe that most oil was formed by tiny organisms at sea. The oil and gas was formed under intense pressure and heat through time in a source rock, typically sedimentary rock. The most common form of source rock is called black shale, an organic-rich sedimentary rock that was created in ancient sea bottoms. The business of finding oil-oil exploration-is in and of itself a difficult and nearly always expensive business venture. Lying hundreds or thousands of feet below the surface, the earliest oil and gas deposits were located by geologic seepage to the surface. Some of the earliest production sites for oil were the results of seepages, including Pennsylvania in the United States, Baku in what is Azerbaijan today, and Trinidad in the Caribbean (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). Submarine seepage, oil seepage occurring naturally from the ocean floor, was also responsible for discovery of some of the earliest oil production areas in the ocean, including those in California off Santa Barbara and the vast deposits of offshore Venezuela. Marine seepage continues today in different areas, including the Gulf of Mexico, where the Department of Energy has estimated that there may be as many as 5,000 active seeps. Most of the earliest oil drilling was in and around the seepages. For a number of years in the late 19th century, some drillers had luck drilling in sitesWeek 2 - Various Key Components in the Oil and Gas Industry Corporate Governance and Behavioral Change in the Oil and Gas Industry Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett (2011), defined corporate governance as "the formal structures, informal structures, and processes that exist in oversight roles and responsibilities in the corporate context". This implies that those charged with governance should ensure that these structures exist and are guided towards the attainment of the company's overall goal and accountability to shareholders. Furthermore, the academic literature on corporate governance examines the corporate governance mechanisms and/or characteristics and how they affect financial performance, disclosure, corporate social responsibility as well as environmental performance of companies. Sheleifer and Vishny (1997) argue that corporate governance mechanisms consist of both legal and economic institutions which can be changed using the political process. This implies that corporate governance mechanisms may be instrumental to effecting change in an organization. Hence, it can be argued that, in order to achieve the World Bank zero routine flaring by 2030, these mechanisms may be useful in ensuring that appropriate decisions are taken when considering whether to flare or utilize gas. Additionally, Haniffa and Hudaib (2006) suggested that corporate governance mechanisms are influenced by a variety of board structure variables including shareholdings by insiders and outsiders, market for corporate control and debt financing. The issues of board structure variables influencing corporate governance mechanisms which have emerged over the years all have practical implications. Even in developed economies, the debate as to how effective or ineffective board structures are is ongoing. For example, it is argued that one way to assess the effectiveness of the board is to look at the quality of decisions. The quality of decisions made by the board is argued to be affected by board size, board independence, the number of outside directors, and board leadership amongst others (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). The reality of the adverse environmental footprints left by the oil and gas companies in the course of flaring gas cannot be overemphasized. It has been shown that the corporate governance structures in companies and the decisions made by those charged with governance have a role to play in ensuring that the gas flared is converted, rechanneled or stopped. There is a consensus of opinion on the high level of impact the board of directors can have in the decision-making processes of companies. It is therefore believed that the board of directors can influence the companies to behave in an environmentally friendly manner. Unfortunately, this is not the case in some of the countries with a thriving oil and gas industry (Dinkpa, 2016). There has been an upsurge in quest for good corporate governance among companies in various nat 2/6 a decade. Corporate governance has assumed a significant position in driving firm's value creation and limp uving financial performance especially in the face of consistent corporate scandals that have continued to rock corporate entities globally. Various theoretical and empirical studies have been occasioned by corporate governance failures both at local and international level yet daily occurrence of financial scandals are on the increase. Corporate governance refers to the control of corporate policy through the power legally vested in a group or groups of people to chart a course of action to be followed by the organization in areas of fundamental importance to its survival, prosperity and proper functioning. It encompasses the mode of structure, the power that determines the rights and responsibilities of the various groups involved in running the organization, the legitimate expectation of the business, the method of operating and the overall accountability of management and of the directors (Ayodele, Aderemi, Obigbemi, & Ojeka, 2016) Access, Leasing, and Exploration of Oil and Gas Finding, developing, and producing crude oil and natural gas are the core activities in the upstream end of the oil and gas value chain. Access, leasing, and exploration activities are the starting point in the value chain because if a firm does not acquire new oil and gas reserves, there will be no new development and production opportunities. Finding new oil and gas reserves is not just about the technology and cost of seismic analysis and deepwater drilling, but also about the laws, regulations, leases, auctions, and permits required by authorities and mandated by governments globally. It is also about forming and managing partnerships, developing innovative new technologies to find oil and gas, negotiating complex deals, and working within the complex geopolitics of the industry (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). As per Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett (2011), opportunity, time, expertise, money, and a little luck are often identified as the five basic elements of oil and gas success. Luck notwithstanding, all successful petroleum developments involve many steps: . Identification of oil and gas field targets . Gaining legal access to exploration and development targets . Generation and analysis of appraisal data . Analysis of exploration discoveries Commercial arrangements such as project finance and negotiating contracts for production output . Final investment decision (FID), when a company commits to recovering the oil and/or gas . Field development & Field production Oil & Gas Formation Crude oil and natural gas occur in nature and are complex combinations of carbon and hydrogen atoms. Both are formed from organic matter-"dinosaurs and diatoms" as the old expression goes, although geologists now believe that most oil was formed by tiny organisms at sea. The oil and gas was formed under intense pressure and heat through time in a source rock, typically sedimentary rock. The most common form of source rock is called black shale, an organic-rich sedimentary rock that was created in ancient sea bottoms. The business of finding oil-oil exploration-is in and of itself a difficult and nearly always expensive business venture. Lying hundreds or thousands of feet below the surface, the earliest oil and gas deposits were located by geologic seepage to the surface. Some of the earliest production sites for oil were the results of seepages, including Pennsylvania in the United States, Baku in what is Azerbaijan today, and Trinidad in the Caribbean (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). Submarine seepage, oil seepage occurring naturally from the ocean floor, was also responsible for discovery of some of the earliest oil production areas in the ocean, including those in California off Santa Barbara and the vast deposits of offshore Venezuela. Marine seepage continues today in different areas, including the Gulf of Mexico, where the Department of Energy has estimated that there may be as many as 5,000 active seeps. Most of the earliest oil drilling was in and around the seepages. For a number of years in the late 19th century, some drillers had luck drilling in sites1:12 PM . Topic Overview - Intro... ... UNICAF Week 1 - Introduction to Oil and Gas Industry Introduction to Oil and Gas Industry The oil and gas industry is one of the largest, most complex, and important global industries. The industry touches everyone's lives with products such as transportation, heating, and electricity fuels; asphalt; lubricants; propane; and thousands of petrochemical products from carpets to eyeglasses to clothing. The industry impacts national security, elections, geopolitics, and international conflicts. The prices of crude oil and natural gas are probably the two most closely watched commodity prices in the global economy (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). Since the beginning of the oil industry, petroleum producers and consumers have feared that eventually the oil would run out. In 1950, the US Geological Survey estimated that the world's conventional recoverable resource base was about 1 trillion barrels. Fifty years later, that estimate had tripled to 3 trillion barrels. In recent years, the concept of peak oil has been much debated. The peak oil theory is based on the fact that the amount of oil is finite. As per Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett (2011), discovering new oil and gas reserves is the lifeblood of the industry. Without new reserves to replace oil and gas production, the industry would die. However, measuring and valuing reserves is a scientific and business challenge because reserves can only be measured if they have value in the marketplace. The oil and gas industry employs hundreds of thousands of workers worldwide and generates billions of dollars globally each year. It is easy to say that this industry is a global powerhouse As per Eikeland (2007), the industry is divided into three major stages: Upstream, midstream, and downstream. Upstream is also known as exploration and production stage and involves the search for underwater underground oil and gas deposits. The drilling of exploration wells is the main activity of this stage. 2/4 The second stage, midstream, refers to the collection and transportation of crude oil, natural gas, and refined products, usually via pipeline, oil tanker, barge, truck or rail. This stage also includes the storage of products as well as any wholesale marketing efforts (Eikeland, 2007). Downstream is the filtering of the raw materials obtained during the upstream phase. Long story short, this means refining crude oil and purifying natural gas. The products generated from this section of the process include natural gas, diesel oil, petrol, gasoline, lubricants, kerosene, jet fuel, asphalt, heating oil, LPG, just to name a few. While each stage is different, each plays a critical role in the overall process. Together all three stages help power the world Eikeland, 2007) The oil and gas industry requires miles and miles of mechanical pipe insulation to maintain low thermal conductivity, reduce heat loss, and insulate against freezing temperatures. Low temperatures and high pressures can quickly form deposits that clog flowlines. Using industrial insulation is a cost-effective solution for maintaining temperature and flow rates, optimizing productivity, and reducing processing costs. The gas and oil industry has been extremely successful since the discovery of oil and will continue to experience growth in the years to come. As this industry continues to grow, the demand for reliable and durable insulation solutions has never been greater (Eikeland, 2007). Oil and Gas in the Global Economy. The Players Oil and gas play a vital role in the global economy. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that energy demand will rise by an average of 1.5% each year through 2030. Demand in 2030 will be about 60% higher than in 2000. Demand in the non-OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) nations will account for approximately 80% of the global increase. Most of the world's growing energy needs through 2030 will continue to be met by oil, gas, and coal. With increased energy efficiency, energy as a percentage of the total gross domestic product (GDP) has fallen and is expected to continue to fall. Oil and gas supply one of the fascinating aspects of the industry is the fact that all countries are consumers of products derived from the oil and gas industry, but only a small set of nations are major producers of oil and gas. Over the past decades, the large developed economies of the world have become net importers of oil and gas, giving rise to challenging geopolitical issues involving a diverse set of oil consumers and producers (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). The global oil and gas industry is made up of thousands of firms of all shapes, sizes, and capabilities. The industry may suffer from an overabundance of terminology when describing these players, so here is some clarification of names and identities (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011, p.g. 11-12): Independent. A nonintegrated company generating nearly all its revenue from either oil and gas production or downstream activities. The term independent is sometimes used more narrowly to refer only to oil and gas producers and not downstream firms. . Integrated oil company (IOC). A company that competes in the upstream, midstream, downstream, and perhaps petrochemicals. IOC is a term usually used in reference to large oil and gas companies-BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, Shell, and Total-and could also include smaller firms such as Eni and Marathon. International oil company (IOC). An oil and gas company that competes across borders. More generally, the term is used to describe the largest oil and gas companies that compete globally and often operate in partnership with NOCs in the NOC's home country. Because most IOCs are involved in oil and gas, a more appropriate term would be international energy company. Confusingly, international oil companies and integrated oil companies both use the1: 14 P MS . Topic Overview - Intro... . . . . National oil company (NOC). A company controlled by a national government, usually formed to manage the country's hydrocarbon resources. Many NOCs, such as Gazprom, Petrobras, and Sinopec, are majority owned by the state and partially owned by private investors. NOCs are usually an arm of a government ministry, such as the ministry of petroleum or ministry of oil and gas. Some NOCs operate only in their home country (e.g., Pemex), and others compete globally across multiple sectors much like an IOC (e.g., Gazprom, Petrobras, and Statoil). As the NOCs get larger and more global, and list their shares, the boundaries are blurring between IOCs and NOCs. Oil major. These are the large non-state-owned oil and gas companies. Although they are typically publicly traded companies, they may also be privately owned. The terms oil majors and IOCs are often used interchangeably. Supermajor. A term used to describe the largest IOCs/oil majors, usually BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, Shell, and Total. The organizations that have dominated the global oil and gas industry for more than a century have changed dramatically over time-in who they are, what they do, and of critical significance for the future of the Industry, what they want. Figure 1-3 lists the largest oil and gas companies by market capitalization (share price times number of shares outstanding). The list includes both IOCs (international oil companies) and NOCs (national oil companies) and is evidence of two factors: mergers and acquisitions, and the global nature of the industry in production and ownership. Based on market capitalization, the top 15 publicly traded (and in some cases, government-controlled) companies include a diverse and global set of firms such as Petrochina (China), Gazprom Russia), Sinopec (China), Petrobras (Brazil), Total (France), and Eni (italy). The Oil and Gas Industry Value Chain In every industry, there are various activities that must take place to transform inputs of raw materials, knowledge, labor, and capital into end products purchased by customers. A value chain is a device that helps identify the independent, economically viable segments of an industry. Value refers to what customers are willing to pay for, and so the value chain helps to identify the specific activities that create value throughout the chain. Companies can use value chains to determine where they are strong and where they have limited competitive strength (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). All industries have upstream (close to raw materials and basic inputs) and downstream close to the customer) segments. In the oil and gas industry, the terms upstream, downstream, and midstream are important descriptors of the industry activities. In fact, these terms have existed far longer than the value chain concept, which emerged in the 1980s. The oil and gas industry value chain is shown in figure 1-8. There are three main segments: upstream, midstream, and downstream. At the far upstream end, the industry starts with exploration ights. At the downstream end products are sold to end users. Each of the different segments could be performed by a standalone firm. For example, consider a deepwater upstream development project. An IOC may do the exploration and then manage the development and production of an oil field. The development will involves many other firms to perform activities such as drilling, ship or rig-building, subsea pipe design, production support and equipment installation, and the supply of many different types of equipment and services. Overall, the oil and gas industry value chain incorporates thousands of firms. Some are specialists or niche players, and others perform many different activities from exploration to retail fuels marketing. Upstream (Exploration & Production) Midstream Downstream (Transportation & Trading) Refining & Marketing) Lease Access Motor Fuels Exploration Oil Trading (gas/diesel) Transportation Jet Fuel R&D Development Ship, Pipeline Refining Heating Oil Production Lubricants Asphalt Gas Petrochemicals Specialty Chemicals Commodity Chemicals Gas Processing Transportation Pipeline Gas to Market LNG Liquefaction Transportation Ship -LNG Regasification Figure 1-8. Global oil and gas value chain References Eikeland, P. O. (2007). Downstream natural gas in Europe-High hopes dashed for upstream oil and gas companies. Energy Policy, 35(1), 227-237. Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett (2011). The Global Oil & Gas Industry : Management, Strategy & Finance, PennWell Corporation. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unicaf/detail.action?docID=3385330. 4/4Week 3 - Oil & Gas Pricing and Financial Performance Oil and Gas Industry/ Financial Performance Rules of thumb have long been used in the energy industry to relate natural gas prices to those for crude oil. Two simple rules use constant ratios between natural gas and crude oil prices. One seems to fit historical data, and one roughly reflects the difference in energy content between the commonly sold units of oil and natural gas. A third rule tries to relate parity in pricing of natural gas and residual fuel oil at the burner tip to prices for natural gas and crude oil at major trading hubs. Gas prices have fallen since 2008 for both immediate and future delivery. However, they have recently recovered somewhat (Brown & Yucel, 2008). All business owners know that having access to capital, at acceptable costs, is critical for the conduct and growth of the business. The global oil and gas industry is no different, although its capital needs are growing more rapidly than most other industry sectors. A number of different forces have driven many changes to the financing of the oil and gas industry in the past 30 years as below (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011, p.g. 257): First, as the upstream global oil and gas industry has had to reach ever farther and deeper to find new reserves, the capital required has increased dramatically. New developments like those in the Caspian, offshore Brazil, sub-Saharan Africa, or even shale gas deposits in the US Midwest, all require more capital per well and per barrel than ever before. And they all are taking longer to initiate and execute. . Second, these remote and difficult projects carry significantly more risk than ever before. Risk, when associated with access to capital, means less capital available and higher cost for that which is available. This risk has forced many players in the oil and gas value chain to get more creative in how they organize and fund projects, including who they take on as partners. . Third is the growing power of the state. The fiscal regimes described in chapter 6 implicitly assumed that the international oil companies provided all of the capital for exploration and development. Although this was often the case historically, in many countries the state has taken a larger role in the development of petroleum projects-and its returns. As a result, financing is now coming from a number of different sources as government entities are increasingly active participants. Fourth, as the basic costs of crude oil and natural gas feedstock have risen in recent years, the downstream sectors of the industry have worked to increase their efficiency in yields, requiring investment in new and more expensive technology. Although the technology will yield its own return, that return is often spread further out over many years. All businesses, whether product or service providers, require capital. The amount of capital needed differs greatly across businesses depending on the type of company and its products or services. The three major financial statements that characterize the financial and operating results of any company are the income statement, the balance sheet, and the statement of cash flows (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). As a consumer, you may already understand the microeconomic implications of higher oil prices. When observing higher oil prices, most of us are likely to think about the price of gasoline as well, since gasoline purc' necessary for most households. When gasoline prices increase, a larger share of households' budget 2 / 4 spent on it, which leaves less to spend on other goods and services. The same goes for businesses who -st be shipped from place to place or that use fuel as a major input (such as the airline industry). Higher oil prices tend to make production more expensive for businesses, just as they make it more expensive for households to do the things they normally do. It turns out that oil and gasoline prices are indeed very closely related. Figure 3 plots average monthly oil prices from 1990 through early 2008, using the spot oil price for West Texas intermediate (right scale, thin blue line, measured in dollars per barrel) and the U.S. retail gasoline price (left scale, thick red line, measured in cents per gallon). The two series track each other very closely over time: increases in oil prices are accompanied by increases in gasoline prices. As shown in the graph, the correlation coefficient (denoted "r") for the two series is 0.98. Moreover, the monthly changes in oil prices and gasoline prices also are very highly and positively correlated. Figure 3. U.S. Gasoline and Oil Prices U.S. Retail Gasoline Price: Regular Grade Avg, Cents/Gallon Spot Oil Price: West Texas Intermediate [Prior'82=Posted Price] $/Barrel 320- r = 0.98 100 280- 240- 200- 160- 40 -20 80- 90 1 1 1 195 05 Sources: DOE, WSJ /Haver 06/24/08 So, when oil prices spike, you can expect gasoline prices to spike as well, and that affects the costs faced by the vast majority of households and businesses. What effects do oil prices have on the "macro" economy? I've just explained how oil prices affect households and businesses; it is not a far leap to understand how oil prices affect the macro-economy. Oil price increases are generally thought to increase inflation and reduce economic growth. In terms of inflation, oil prices directly affect the prices of goods made with petroleum products. As mentioned above, oil prices indirectly affect costs such as transportation, manufacturing, and heating. The increase in these costs can in turn affect the prices of a variety of goods and services, as producers may pass production costs on to consumers. The extent to which oil price increases lead to consumption price increases depends on how important oil is for the production of a given type of good or service. Oil price increases can also stifle the growth of the economy through their effect on the supply and demand for goods other than oil. Increases in oil prices can depress the supply of other goods because they increase the costs of producing them. In economics terminology, high oil prices can shift up the supply curve for the goods and services for which oil is an input.1:16 PM . F Topic Overview - Oil... Q ... UNICAF Week 3 - Oil & Gas Pricing and Financial Performance Oil and Gas Industry/ Financial Performance Rules of thumb have long been used in the energy industry to relate natural gas prices to those for crude oil. Two simple rules use constant ratios between natural gas and crude oil prices. One seems to fit historical data, and one roughly reflects the difference in energy content between the commonly sold units of oil and natural gas. A third rule tries to relate parity in pricing of natural gas and residual fuel oil at the burner tip to prices for natural gas and crude oil at major trading hubs. Gas prices have fallen since 2008 for both immediate and future delivery. However, they have recently recovered somewhat (Brown & Yucel, 2008). All business owners know that having access to capital, at acceptable costs, is critical for the conduct and growth of the business. The global oil and gas industry is no different, although its capital needs are growing more rapidly than most other industry sectors. A number of different forces have driven many changes to the financing of the oil and gas industry in the past 30 years as below (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011, p.g. 257): . First, as the upstream global oil and gas industry has had to reach ever farther and deeper to find new reserves, the capital required has increased dramatically. New developments like those in the Caspian, offshore Brazil, sub-Saharan Africa, or even shale gas deposits in the US Midwest, all require more capital per well and per barrel than ever before. And they all are taking longer to initiate and execute. Second, these remote and difficult projects carry significantly more risk than ever before. Risk, when associated with access to capital, means less capital available and higher cost for that which is available. This risk has forced many players in the oil and gas value chain to get more creative in how they organize and fund projects, including who they take on as partners. . Third is the growing power of the state. The fiscal regimes described in chapter 6 implicitly assumed that the international oil companies provided all of the capital for exploration and development. Although this was often the case historically, in many countries the state has taken a larger role in the development of petroleum projects-and ts returns. As a result, financing is now coming from a number of different sources as government entities are increasingly active participants. Fourth, as the basic costs of crude oil and natural gas feedstock have risen in recent years, the downstream sectors of the industry have worked to increase their efficiency in yields, requiring investment in new and more expensive technology. Although the technology will yield its own return, that return is often spread further out over many years. All businesses, whether product or service providers, require capital. The amount of capital needed differs greatly across businesses depending on the type of company and its products or services. The three major financial statements that characterize the financial and operating results of any company are the income statement, the balance sheet, and the statement of cash flows (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). As a consumer, you may already understand the microeconomic implications of higher oil prices. When observing higher oil prices, most of us are likely to think about the price of gasoline as well, since gasoline purc' necessary for most households. When gasoline prices increase, a larger share of households' budget 2/4 spent on it, which leaves less to spend on other goods and services. The same goes for businesses whu be shipped from place to place or that use fuel as a major input (such as the airline industry). Higher oil prices tend to -st make production more expensive for businesses, just as they make it more expensive for households to do the things they normally do. It turns out that oil and gasoline prices are indeed very closely related. Figure 3 plots average monthly oil prices from 1990 through early 2008, using the spot oil price for West Texas intermediate (right scale, thin blue line, measured in dollars per barrel) and the U.S. retail gasoline price (left scale, thick red line, measured in cents per gallon). The two series track each other very closely over time: increases in oil prices are accompanied by increases in gasoline prices. As shown in the graph, the correlation coefficient (denoted "r") for the two series is 0.98. Moreover, the monthly changes in oil prices and gasoline prices also are very highly and positively correlated. Figure 3. U.S. Gasoline and Oil Prices U.S. Retail Gasoline Price: Regular Grade Avg. Cents/Gallon Spot Oil Price: West Texas Intermediate [Prior'82=Posted Price] 320- $/Barrel r = 0.98 100 280 240- 200- 160- - 40 120-/ -20 05 Sources: DOE, WSJ /Haver 06/24/08 So, when oil prices spike, you can expect gasoline prices to spike as well, and that affects the costs faced by the vast majority of households and businesses. What effects do oil prices have on the "macro" economy? I've just explained how oil prices affect households and businesses; it is not a far leap to understand how oil prices affect the macro-economy. Oil price increases are generally thought to increase inflation and reduce economic growth. In terms of inflation, oil prices directly affect the prices of goods made with petroleum products. As mentioned above, oil prices indirectly affect costs such as transportation, manufacturing, and heating. The increase in these costs can in turn affect the prices of a variety of goods and services, as producers may pass production costs on to consumers. The extent to which oil price increases lead to consumption price increases depends on how important oil is for the production of a given type of good or service. Oil price increases can also stifle the growth of the economy through their effect on the supply and demand for goods other than oil. Increases in oil prices can depress the supply of other goods because they increase the costs of producing them. In economics terminology, high oil prices can shift up the supply curve for the goods and services for which oil is an input.1:17 PM . Topic Overview - Oil... Q ... oil. The extra payment that U.S. consumers make to foreign oil producers can now no longer be spent on other kinds of consumption goods. Despite these effects on supply and demand, the correlation between oil price increases and economic downturns, not every sizeable oil price increase has been followed by a recession. However, five of the last seven U.S. recessions were preceded by considerable increases in oil prices (Blanchard & Gali, 2007). Is the relationship between oil prices and the economy always the same? The two aforementioned large oil shocks of the 1970s were characterized by low growth, high unemployment, and high inflation (also often referred to as periods of stagflation). It is no wonder that changes in oil prices have been viewed as an important source of economic fluctuations. However, in the past decade research has challenged this conventional wisdom about the relationship between oil prices and the economy. As Blanchard and Gali (2007), the late 1990s and early 2000s were periods of large oil price fluctuations, which were comparable in magnitude to the oil shocks of the 1970s. However, these later oil shocks did not cause considerable fluctuations in inflation (Figure 4), real GDP growth (Figure 5), or the unemployment rate. Figure 4. Oil Prices and CPI Inflation CPI-U: All Items % Change - Year to Year SA, 1982-84-100 Spot Oil Price: West Texas Intermediate [Prior*82-Posted Price] 15.0 $/Barrel + 100 12.5- 10.0- -60 7.5- 5.0- 2.5- 0.0 65 76 75 60 85 50 55 50 5 0 Sources: BLS, WSJ /Haver 06/24/08 Figure 5. Oil Prices and Real GDP Growth Real Gross Domestic Product % Change - Year to Year SAAR, Bil. Chn.2000$ Spot Oil Price: West Texas Intermediate [Prior*82=Posted Price] 10.0- $/Barrel 5.0- 0.0- -40 -2.5- -20 0 65 50 75 8 Sources: BEA, WSJ /Haver 85 50 35 60 65 06/24/08 References Blanchard, O. J., & Gali, J. (2007). The Macroeconomic Effects of Oil Shocks: Why are the 2000s so different from the 1970s? (No. w13368). National bureau of economic research. Brown, S. P., & Yucel, M. K. (2008). What drives natural gas prices?. Energy Journal, 29(2), 45. Fernald, John, and Bharat Trehan. (2005). "Why Hasn't the Jump in Oil Prices Led to a Recession?" FRBSF Economic Letter 2005-31. Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett. The Global Oil & Gas Industry : Management, Strategy & Finance, PennWell Corporation, 2011. ProQuest Ebook Central, https:/ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unicaf/detail.action?docID=3385330. 4/41:19 PM . Topic Overview - Vario... ... approach to be taken in determining where and how deep to drill. Two major developments were: Surface topography. The major development in these early years was the increased mapping of sedimentary rock formations on the surface, and then projecting much of this surface mapping to subsurface sedimentary rock formation maps (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). Seismology. The logical next steps in subsurface mapping and geologic analysis was in the development of seismic technology, in which sound waves are initiated from a source (such as dynamite or an air cannon), bounced off subsurface geologic structures, and subsequently recorded by a detector of some sort on the surface. This led to an increasingly sophisticated and detailed mapping of subsurface rock layers and formations. Oil exploration today is much more science than art. The use of technology in determining the locations of likely oil traps continues to develop rapidly. Geologists, the true "rock hunters" who wander the earth in search of oil, use a variety of increasingly sophisticated techniques ranging from surface topography, soil types, satellite imaging, magnetometers, and seismology (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). Access and Development Rights E&P firms will strategically identify target areas where they believe hydrocarbon resources exist, such as the Gulf of Mexico or offshore West Africa. However, before any real exploration activities can begin, the firm must gain legal access to the target area. The right to explore and develop, involving mineral rights or subsurface rights, is typically held by the state (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). The right to explore and develop Gaining access to property in order to explore for oil and gas is first about ownership and who owns the rights. Are the rights owned by the person who owns the land that sits atop the oil? The local community? The government of the community? The federal government capital many miles away? With few exceptions, most notably Canada and the United States, most of the world's subsurface mineral and resource rights are held by a state government. Most countries have a legal structure covering both the responsibilities of the developer (lessee) and the mineral rights owner (lessor). These agreements, generically called fiscal regimes for international petroleum agreements (IPAs), have become synonymous with the financial "split" between the two parties over the life of the reservoir. Much of the early oil exploration began with the right to explore. If oil was discovered, a separate and more detailed agreement would be negotiated between the developer and the rights holder (typically the state). A full developm ement, including distinctions of whether the developer takes ownership to the oil and gas or simply acts a service provider, as well as any applicable royalties, license fees, profit or cost oil splits, etc., are now included in the fiscal regime of the country (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). Fiscal Regimes, also termed international Petroleum Agreements, are the fundamental set of rules between the lessor and the lessee for the exploration, development, and production of an oil reservoir over its life. Concession Production Sharing Risk Service Royalty/Tax System) Agreement (PSA) Contract property takes title to the gil an party is only a contractst and takes no title to oil or gas produced Lessee usually provides all production capital envelopment, and production Lessee pary's the Messor a royalty (X of price for the life of the proje Lessee pays the host gave Lessee pays the host government corporate incon corporate income taxes and possibly special ail tames takes over the life of the project takes over the the of the project Figure 3-3. Fiscal regimes, also known as international petroleum agreements Royalty/tax systems The modern form of the concession, the royalty/tax system, is much more comprehensive in protect. 4/6 of the state. All four original Concession principles have been changed to balance, if not tip, the scales in favor of the state. The typical royalty/tax system structure today is for a much shorter period of time, a much smaller portion of a potential hydrocarbon deposit, and requires specific exploration and development efforts within a set period of time, or the rights expire. Royalty/tax systems still make up roughly half the fiscal systems used in petroleum development today. Tax rates vary across countries and usually range between 8% and 18%. Sliding-scale royalty systems are also frequently used. The so-called OPEC model used widely in the 1970s, which combined a 20% royalty with an 85% tax rate, resulted in little development interest from IOCs. The OPEC model shows the extreme pendulum swing from the lax concession systems of the 1930s. All costs and expenses related to the development and operation of a single reservoir, field, or block, should be assigned and deducted from the revenues generated solely by that resource unit. This is the concept of ring fencing, which means separating a single reservoir or field from any others for clear identification of revenues and costs. Many governments, including Indonesia, require the establishment of a different and separable company for every field developed in order to eliminate confusion or controversy (from consolidation) related to the revenues and costs for a specific reservoir. Ring fencing increases the cost and complexity of managing the development (Inkpen, Andrew, and Michael Moffett, 2011). Oil and Gas Regulations. Operators Obligations According to Kardel, (2018), Natural resources in general, and oil and gas contracts in particular, are an important and sensitive issue under Iran's legal framework. Since the Islamic revolution, the oil and gas legal framework has been undergoing considerable changes. Internationally, unitization of oil and gas takes place within a multilayered framework of law. When a reservoir straddles the boundaries of two or more sovereign countries, whether the boundaries are defined (often termed 'delimited") or undefined, the layers look like this: (i) international law-treaties, conventions, and international custom; (ii) national laws and regulations of the host governments, and contracts between the host governments and the licensees, notably agreements authorizing development (such as a license agreement, concession, or production- sharing agreement). In some countries, the host-government contract has the force of law; and (iii) private contracts among the licensees and interested third parties, such as operating agreements, farmout and acquisition agreements, and production sales contracts (Weaver & Asmus, 2006). Operators have executed a multitude of oil and gas leases with landowners, and many have acquired acreage that has been held by production from shallower formations.1:20 PM . Topic Overview - Vario... . . . property may be rich in natural resources like precious metals or water. Among the various types of natural resources that might exist on or within a property are oil and gas. As energy-producing substances, oil and gas can be lucrative for those who capture them for consumption. Because there's a lot to gain for miners, and because oil and gas mining requires careful planning and procedures, oil and gas law is a field of law in its own right. Most oil and gas laws are state laws. The federal government has relatively little to say about oil and gas law, but it is involved in leasing and permitting on federal lands. The federal government also regulates offshore drilling. Oil and gas laws determine who may mine for oil and gas, how they may go about mining and what happens when disputes occur. In order to effectively advise their clients, an oil and gas attorney must understand the rule of capture and the correlative rights rule. Under the rule of capture, a landowner may capture and mine all of the oil and gas that sits underneath their land. If a resource runs onto their land from another piece of land, the owner has the right to capture it for their own use. The rule of capture encourages andowners to explore the resources on their property because it allows them to keep what they find. However, the correlative rights rule requires an owner to go about their work without waste or negligence. An owner can't be so eager to mine that they work in a way that prevents complete exploration and capture of the available resources. An oil and gas attorney must help their clients determine how to conduct business in a way that doesn't violate the rules of conduct in the oil and gas industry (Bibikos & King, 2008). References Ayodele, S., Aderemi, A. K., Obigbemi, I. F., & Ojeka, S. A. (2016). Assessing the connectedness between corporate governance mechanisms and financial performance of listed oil and gas companies in nigeria. Journal of Accounting, Finance and Auditing Studies, 2(4), 155-171. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1825569709?accountid=188730 Bibikos, G. A., & King, J. C. (2008). A Primer on Oil and Gas Law in the Marcellus Shale States. Tex. J. Oil Gas & Energy L., 4, 155. Dinkpa, N. E. (2016). CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND BEHAVIORAL CHANGE IN THE OIL AND GAS INDUSTRY: - THE CASE OF GAS FLARING. International Journal of Arts & Sciences, 9(3), 299-309. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1858849740?accountid=188730 Haniffa, R. and Hudaib, M., 2006. Corporate governance structure and perfor