Question- 6. According to IFE (International Fischer Effect), how would U.S. and Switzerland nominal rates compare during the three year period prior to Jan 1985? If Swiss Air had access to capital markets both in the US and in Switzerland, how would you recommend Swiss Air to finance the planes given the nominal rates? Under what circumstances would Swiss Air benefit from financing in one market over the other? (10 points)

Question- 6. According to IFE (International Fischer Effect), how would U.S. and Switzerland nominal rates compare during the three year period prior to Jan 1985? If Swiss Air had access to capital markets both in the US and in Switzerland, how would you recommend Swiss Air to finance the planes given the nominal rates? Under what circumstances would Swiss Air benefit from financing in one market over the other? (10 points)

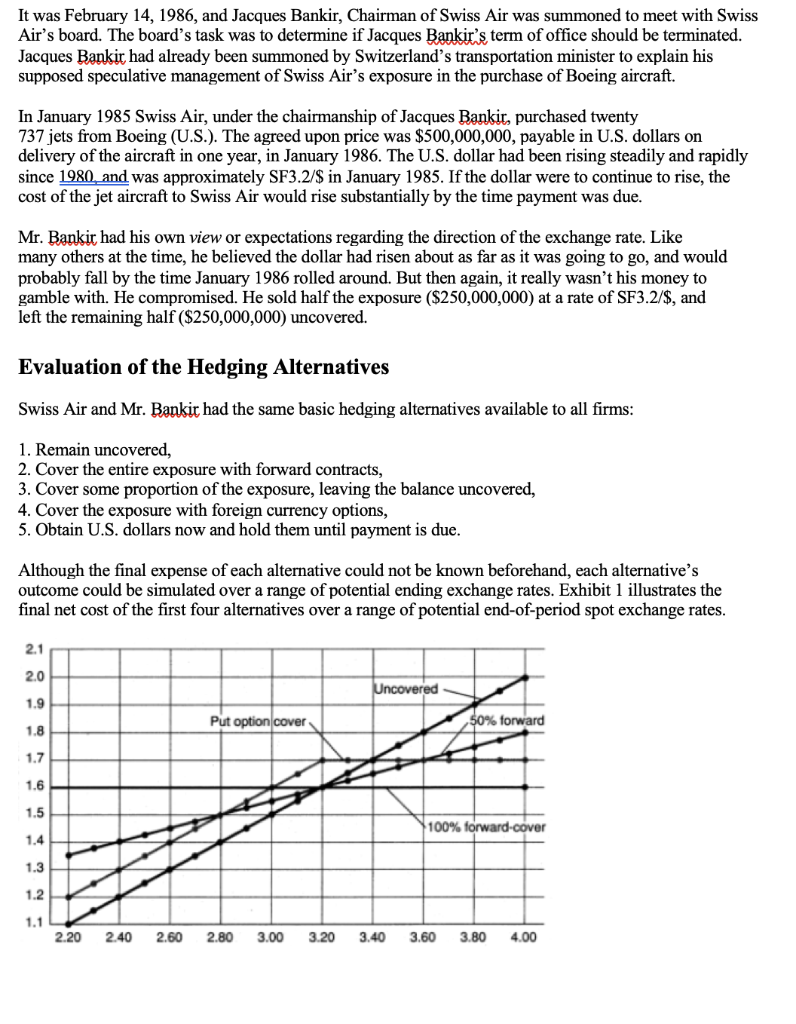

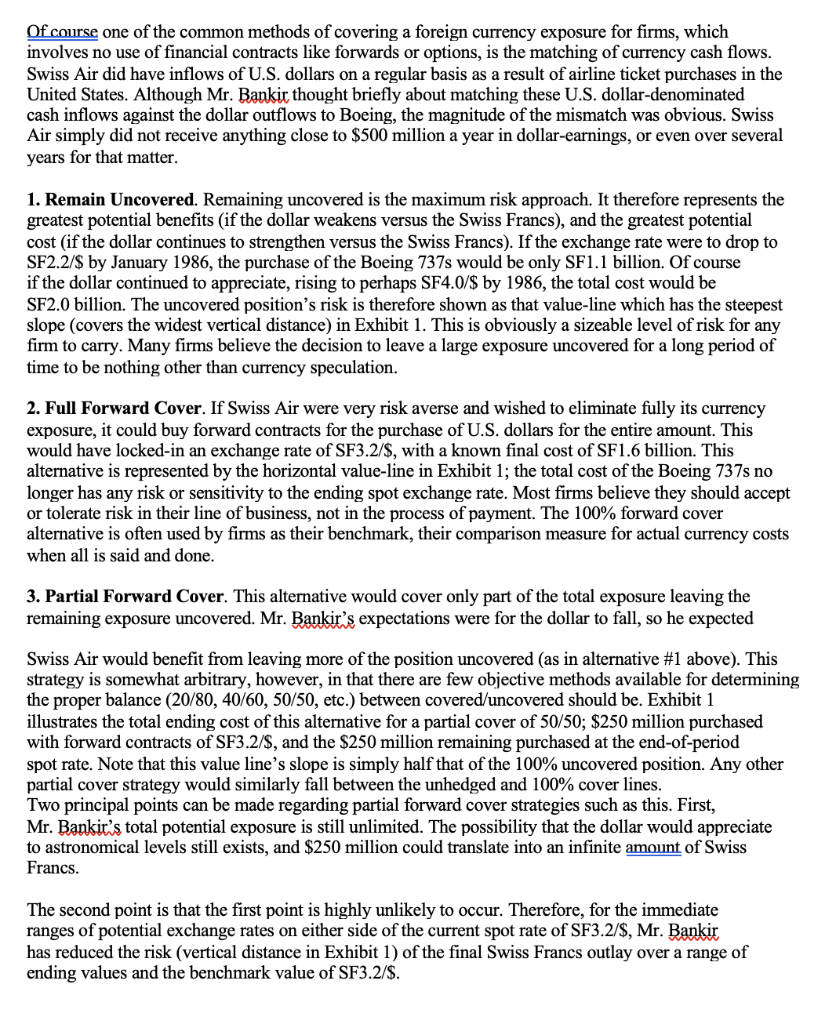

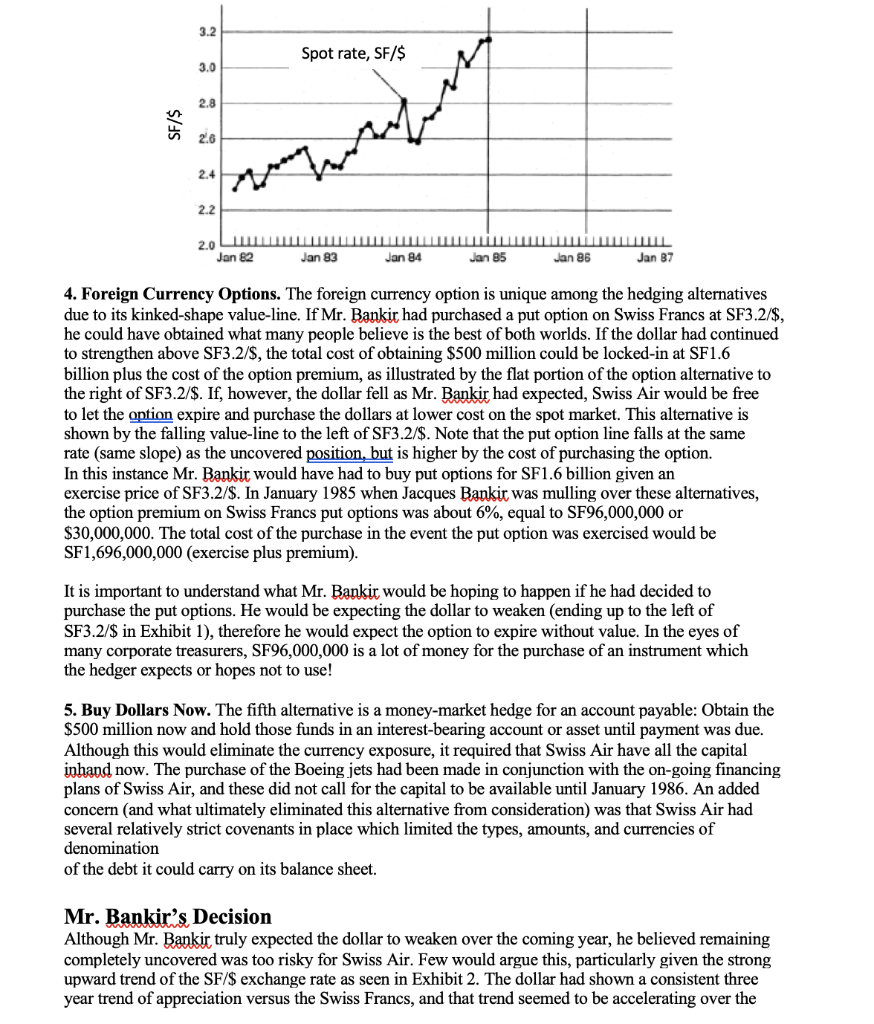

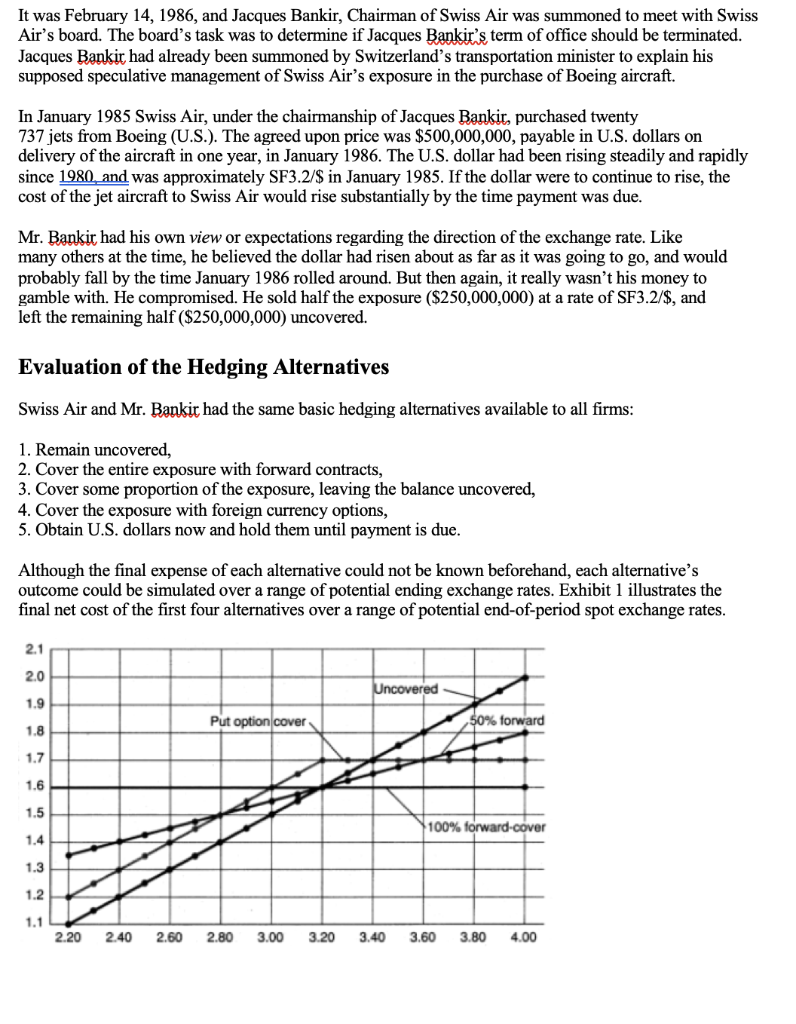

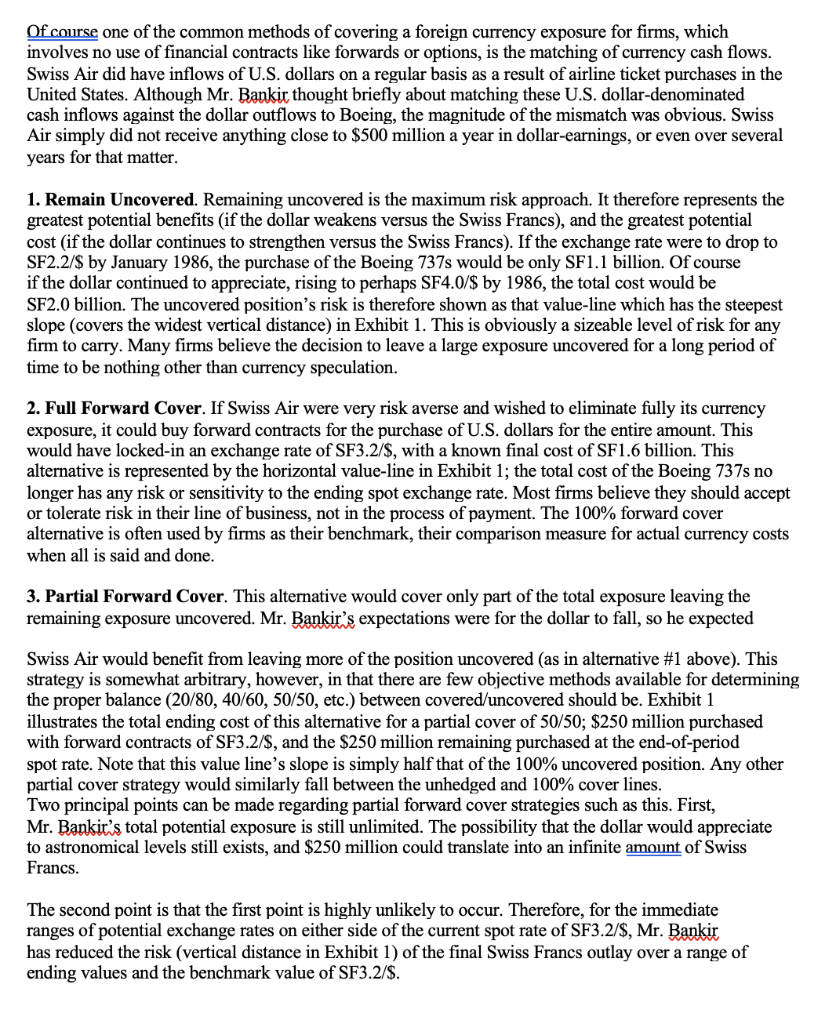

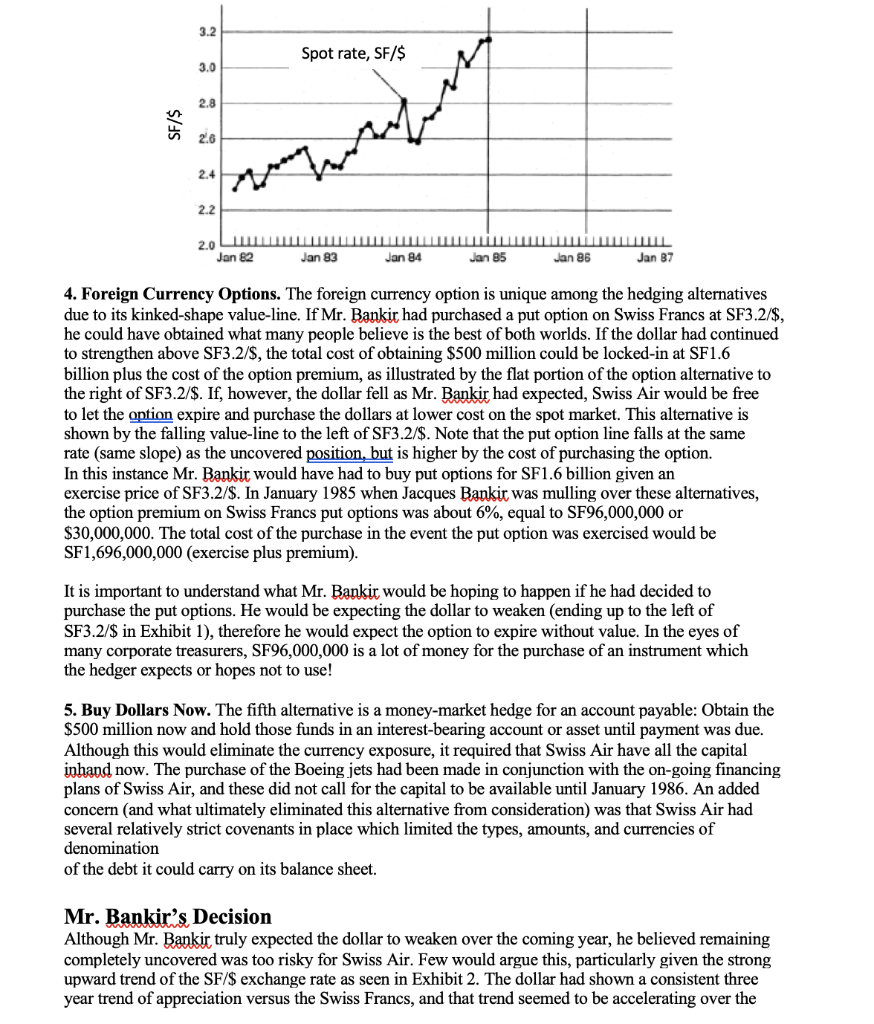

It was February 14, 1986, and Jacques Bankir, Chairman of Swiss Air was summoned to meet with Swiss Air's board. The board's task was to determine if Jacques Bankir's term of office should be terminated. Jacques Bankir had already been summoned by Switzerland's transportation minister to explain his supposed speculative management of Swiss Air's exposure in the purchase of Boeing aircraft. In January 1985 Swiss Air, under the chairmanship of Jacques Bankir, purchased twenty 737 jets from Boeing (U.S.). The agreed upon price was $500,000,000, payable in U.S. dollars on delivery of the aircraft in one year, in January 1986. The U.S. dollar had been rising steadily and rapidly since 1980 and was approximately SF3.2/$ in January 1985. If the dollar were to continue to rise, the cost of the jet aircraft to Swiss Air would rise substantially by the time payment was due. Mr. Bankir had his own view or expectations regarding the direction of the exchange rate. Like many others at the time, he believed the dollar had risen about as far as it was going to go, and would probably fall by the time January 1986 rolled around. But then again, it really wasn't his money to gamble with. He compromised. He sold half the exposure ($250,000,000) at a rate of SF3.2/$, and left the remaining half ($250,000,000) uncovered. Evaluation of the Hedging Alternatives Swiss Air and Mr. Bankir had the same basic hedging alternatives available to all firms: 1. Remain uncovered, 2. Cover the entire exposure with forward contracts, 3. Cover some proportion of the exposure, leaving the balance uncovered, 4. Cover the exposure with foreign currency options, 5. Obtain U.S. dollars now and hold them until payment is due. Although the final expense of each alternative could not be known beforehand, each alternative's outcome could be simulated over a range of potential ending exchange rates. Exhibit 1 illustrates the final net cost of the first four alternatives over a range of potential end-of-period spot exchange rates. 2.1 2.0 Uncovered 1.9 Put option cover 50% forward 1.8 1.7 1.6 1.5 100% forward-cover 1.4 1.3 1.2 1.1 2.20 2.40 2.60 2.80 3.00 3.20 3.40 3.60 3.80 4.00 Of course one of the common methods of covering a foreign currency exposure for firms, which involves no use of financial contracts like forwards or options, is the matching of currency cash flows. Swiss Air did have inflows of U.S. dollars on a regular basis as a result of airline ticket purchases in the United States. Although Mr. Bankir thought briefly about matching these U.S. dollar-denominated cash inflows against the dollar outflows to Boeing, the magnitude of the mismatch was obvious. Swiss Air simply did not receive anything close to $500 million a year in dollar-earnings, or even over several years for that matter. 1. Remain Uncovered. Remaining uncovered is the maximum risk approach. It therefore represents the greatest potential benefits (if the dollar weakens versus the Swiss Francs), and the greatest potential cost (if the dollar continues to strengthen versus the Swiss Francs). If the exchange rate were to drop to SF2.2/$ by January 1986, the purchase of the Boeing 737s would be only SF1.1 billion. Of course if the dollar continued to appreciate, rising to perhaps SF4.0/$ by 1986, the total cost would be SF2.0 billion. The uncovered position's risk is therefore shown as that value-line which has the steepest slope (covers the widest vertical distance) in Exhibit 1. This is obviously a sizeable level of risk for any firm to carry. Many firms believe the decision to leave a large exposure uncovered for a long period of time to be nothing other than currency speculation. 2. Full Forward Cover. If Swiss Air were very risk averse and wished to eliminate fully its currency exposure, it could buy forward contracts for the purchase of U.S. dollars for the entire amount. This would have locked-in an exchange rate of SF3.2/$, with a known final cost of SF1.6 billion. This alternative is represented by the horizontal value-line in Exhibit 1; the total cost of the Boeing 737s no longer has any risk or sensitivity to the ending spot exchange rate. Most firms believe they should accept or tolerate risk in their line of business, not in the process of payment. The 100% forward cover alternative is often used by firms as their benchmark, their comparison measure for actual currency costs when all is said and done. 3. Partial Forward Cover. This alternative would cover only part of the total exposure leaving the remaining exposure uncovered. Mr. Bankir's expectations were for the dollar to fall, so he expected Swiss Air would benefit from leaving more of the position uncovered (as in alternative #1 above). This strategy is somewhat arbitrary, however, in that there are few objective methods available for determining the proper balance (20/80, 40/60, 50/50, etc.) between covered/uncovered should be. Exhibit 1 illustrates the total ending cost of this alternative for a partial cover of 50/50; $250 million purchased with forward contracts of SF3.2/$, and the $250 million remaining purchased at the end-of-period spot rate. Note that this value line's slope is simply half that of the 100% uncovered position. Any other partial cover strategy would similarly fall between the unhedged and 100% cover lines. Two principal points can be made regarding partial forward cover strategies such as this. First, Mr. Bankir's total potential exposure is still unlimited. The possibility that the dollar would appreciate to astronomical levels still exists, and $250 million could translate into an infinite amount of Swiss Francs. The second point is that the first point is highly unlikely to occur. Therefore, for the immediate ranges of potential exchange rates on either side of the current spot rate of SF3.2/$, Mr. Bankir has reduced the risk (vertical distance in Exhibit 1) of the final Swiss Francs outlay over a range of ending values and the benchmark value of SF3.2/$. 3.2 Spot rate, SF/$ 3.0 2.8 2.2 2.0 LLLLL Jan 82 Jan 83 Jan 84 Jan 85 Jan 86 Jan 37 4. Foreign Currency Options. The foreign currency option is unique among the hedging alternatives due to its kinked-shape value-line. If Mr. Bankir had purchased a put option on Swiss Francs at SF3.2/$, he could have obtained what many people believe is the best of both worlds. If the dollar had continued to strengthen above SF3.2/$, the total cost of obtaining $500 million could be locked-in at SF1.6 billion plus the cost of the option premium, as illustrated by the flat portion of the option alternative to the right of SF3.2/$. If, however, the dollar fell as Mr. Bankir had expected, Swiss Air would be free to let the option expire and purchase the dollars at lower cost on the spot market. This alternative is shown by the falling value-line to the left of SF3.2/$. Note that the put option line falls at the same rate (same slope) as the uncovered position, but is higher by the cost of purchasing the option. In this instance Mr. Bankir would have had to buy put options for SF1.6 billion given an exercise price of SF3.2/$. In January 1985 when Jacques Bankir was mulling over these alternatives, the option premium on Swiss Francs put options was about 6%, equal to SF96,000,000 or $30,000,000. The total cost of the purchase in the event the put option was exercised would be SF1,696,000,000 (exercise plus premium). It is important to understand what Mr. Bankir would be hoping to happen if he had decided to purchase the put options. He would be expecting the dollar to weaken (ending up to the left of SF3.2/$ in Exhibit 1), therefore he would expect the option to expire without value. In the eyes of many corporate treasurers, SF96,000,000 is a lot of money for the purchase of an instrument which the hedger expects or hopes not to use! 5. Buy Dollars Now. The fifth alternative is a money-market hedge for an account payable: Obtain the $500 million now and hold those funds in an interest-bearing account or asset until payment was due. Although this would eliminate the currency exposure, it required that Swiss Air have all the capital iphand now. The purchase of the Boeing jets had been made in conjunction with the on-going financing plans of Swiss Air, and these did not call for the capital to be available until January 1986. An added concern (and what ultimately eliminated this alternative from consideration) was that Swiss Air had several relatively strict covenants in place which limited the types, amounts, and currencies of denomination of the debt it could carry on its balance sheet. Mr. Bankir's Decision Although Mr. Bankir truly expected the dollar to weaken over the coming year, he believed remaining completely uncovered was too risky for Swiss Air. Few would argue this, particularly given the strong upward trend of the SF/$ exchange rate as seen in Exhibit 2. The dollar had shown a consistent three year trend of appreciation versus the Swiss Francs, and that trend seemed to be accelerating over the most recent year. Because he personally felt so strongly that the dollar would weaken, Mr. Bankir chose to go with partial cover. He chose to cover 50% of the exposure ($250 million) with forward contracts (the one year forward rate was SF3.2/$) and to leave the remaining 50% ($250 million) uncovered. Because foreign currency options were as yet a relatively new tool for exposure management by many firms, and because of the sheer magnitude of the up-front premium required, the foreign currency option was not chosen. Time would tell if this was a wise decision. How It Came Out Mr. Bankir was both right and wrong. He was definitely right in his expectations. The dollar appreciated for one more month, and then weakened over the coming year. In fact, it did not simply weaken, it plummeted. By January 1986 when payment was due to Boeing, the spot rate had fallen to SF2.3/$ from the previous year's SF3.2/$ as shown in Exhibit 3. This was a spot exchange rate movement in Swiss Air's favor. The bad news was that the total Swiss Francs cost with the partial forward cover was SF1.375 billion, a full SF225,000,000 more than if no hedging had been implemented at all! This was also SF129,000,000 more than what the foreign currency option hedge would have cost in total. The total cost of obtaining the needed $500 million for each alternative at the actual ending spot rate of SF2.3/$ would have been: Alternative Relevant Rate Total SF Cost 1: Uncovered SF 2.3/$ 1,150,000,000 2: Full Forward Cover (100%) SF 3.2/$ 1,600,000,000 3: Partial Forward Cover 1/2(SF2.3) + 2(SF3.2) 1,375,000,000 4: SF Put Options SF 3.2/$ strike 1,246,000,000 Mr. Heinz's political rivals, both inside and outside of Swiss Air, were not so happy. Bankir was accused of recklessly speculating with Swiss Air's money, but the speculation was seen as the forward contract, not the amount of the dollar exposure left uncovered for the full year. 3.4 3.2 Ruhnau could see Ruhnau pould not see 3.0 2.8 2.6 2.4 2.2 2.0 1.8 1.6 Jan 82 Jan 83 Jan 84 Jan 85 Jan 86 Jan 87

Question- 6. According to IFE (International Fischer Effect), how would U.S. and Switzerland nominal rates compare during the three year period prior to Jan 1985? If Swiss Air had access to capital markets both in the US and in Switzerland, how would you recommend Swiss Air to finance the planes given the nominal rates? Under what circumstances would Swiss Air benefit from financing in one market over the other? (10 points)

Question- 6. According to IFE (International Fischer Effect), how would U.S. and Switzerland nominal rates compare during the three year period prior to Jan 1985? If Swiss Air had access to capital markets both in the US and in Switzerland, how would you recommend Swiss Air to finance the planes given the nominal rates? Under what circumstances would Swiss Air benefit from financing in one market over the other? (10 points)