Question

QUESTION: A.) How Attractive was this investment? (FIND NPV) The question is asking for the NPV of the project. Exhibit 9 has the data for

QUESTION:

A.) How Attractive was this investment? (FIND NPV)

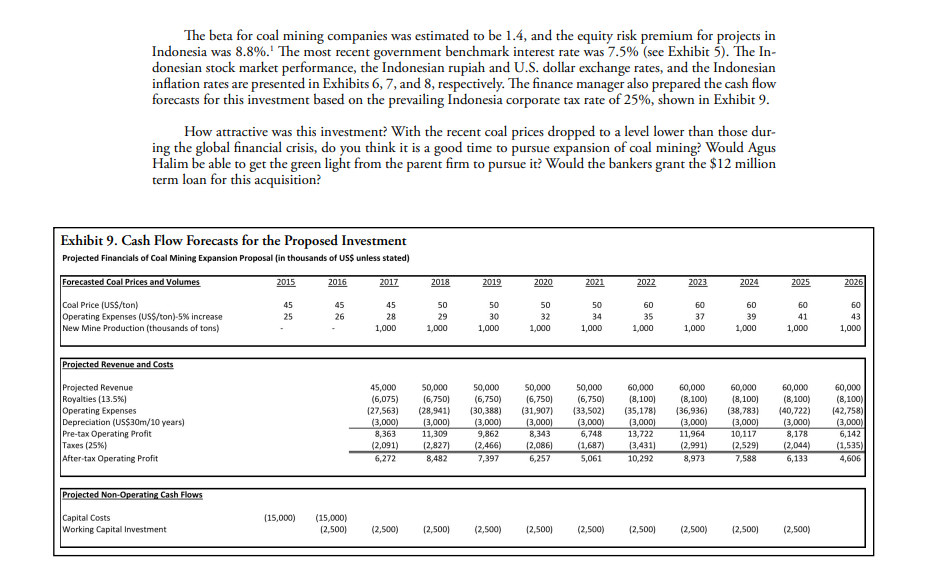

The question is asking for the NPV of the project. Exhibit 9 has the data for calculating NPV. The discount rate to be used for NPV is the WACC. Also, discount rate should be applied to Free-Cash Flow (FCF). When the financial statements are prepared according to GAAP, FCF can be calculated by adding back depreciation to net income (also called after-tax operating profit), adding (subtracting) any decrease (increase) in working capital requirements, and subtracting capital investments. However, these operations are a bit complicated by the non-conventional usage of sign in Exhibit 9. When a standard income statement is prepared, depreciation is written as a positive number. So, the number can be easily added to net income. But for Exhibit 9, depreciation is written as a negative number; so, it has to be subtracted to find FCF. Similarly, increase in working capital would be a positive number in a standard cash-flow statement. But it is negative in Exhibit 9. This means the increase in working capital in Exhibit 9 should be added to find FCF. So, for Exhibit 9, FCF = after-tax operating profit - depreciation + working capital + capital expenditure (in the first two years. They are already negative numbers.).

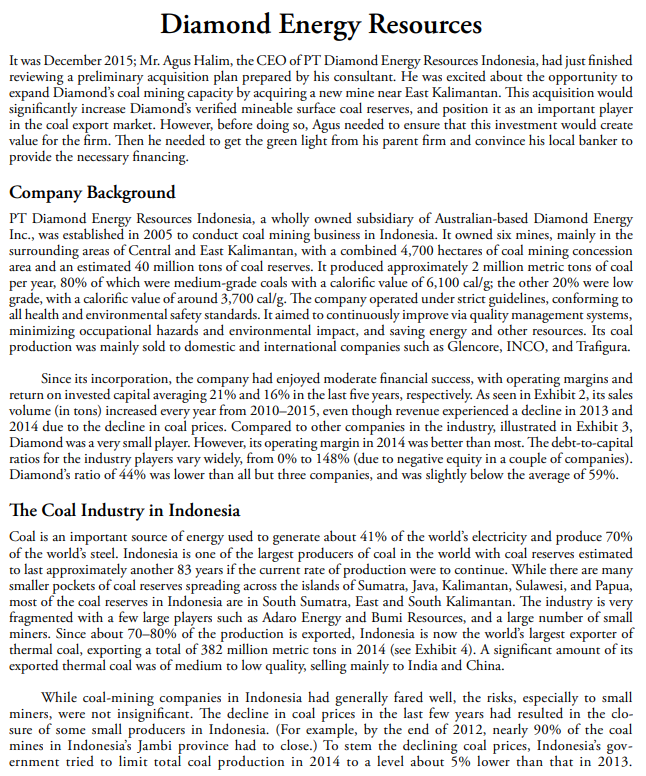

Diamond Energy Resources It was December 2015; Mr. Agus Halim, the CEO of PT Diamond Energy Resources Indonesia, had just finished reviewing a preliminary acquisition plan prepared by his consultant. He was excited about the opportunity to expand Diamond's coal mining capacity by acquiring a new mine near East Kalimantan. This acquisition would significantly increase Diamond's verified mineable surface coal reserves, and position it as an important player in the coal export market. However, before doing so, Agus needed to ensure that this investment would create value for the firm. Then he needed to get the green light from his parent firm and convince his local banker to provide the necessary financing. Company Background PT Diamond Energy Resources Indonesia, a wholly owned subsidiary of Australian-based Diamond Energy Inc., was established in 2005 to conduct coal mining business in Indonesia. It owned six mines, mainly in the surrounding areas of Central and East Kalimantan, with a combined 4,700 hectares of coal mining concession area and an estimated 40 million tons of coal reserves. It produced approximately 2 million metric tons of coal per year, 80% of which were medium-grade coals with a calorific value of 6,100 cal/g; the other 20% were low grade, with a calorific value of around 3,700 cal/g. The company operated under strict guidelines, conforming to all health and environmental safety standards. It aimed to continuously improve via quality management systems, minimizing occupational hazards and environmental impact, and saving energy and other resources. Its coal production was mainly sold to domestic and international companies such as Glencore, INCO, and Trafigura. Since its incorporation, the company had enjoyed moderate financial success, with operating margins and return on invested capital averaging 21% and 16% in the last five years, respectively. As seen in Exhibit 2, its sales volume (in tons) increased every year from 2010-2015, even though revenue experienced a decline in 2013 and 2014 due to the decline in coal prices. Compared to other companies in the industry, illustrated in Exhibit 3, Diamond was a very small player. However, its operating margin in 2014 was better than most. The debt-to-capital ratios for the industry players vary widely, from 0% to 148% (due to negative equity in a couple of companies). Diamond's ratio of 44% was lower than all but three companies, and was slightly below the average of 59%. The Coal Industry in Indonesia Coal is an important source of energy used to generate about 41% of the world's electricity and produce 70% of the world's steel. Indonesia is one of the largest producers of coal in the world with coal reserves estimated to last approximately another 83 years if the current rate of production were to continue. While there are many smaller pockets of coal reserves spreading across the islands of Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua, most of the coal reserves in Indonesia are in South Sumatra, East and South Kalimantan. The industry is very fragmented with a few large players such as Adaro Energy and Bumi Resources, and a large number of small miners. Since about 70-80% of the production is exported, Indonesia is now the world's largest exporter of thermal coal, exporting a total of 382 million metric tons in 2014 (see Exhibit 4). A significant amount of its exported thermal coal was of medium to low quality, selling mainly to India and China. While coal-mining companies in Indonesia had generally fared well, the risks, especially to small miners, were not insignificant. The decline in coal prices in the last few years had resulted in the clo- sure of some small producers in Indonesia. (For example, by the end of 2012, nearly 90% of the coal mines in Indonesia's Jambi province had to close.) To stem the declining coal prices, Indonesia's gov- ernment tried to limit total coal production in 2014 to a level about 5% lower than that in 2013. a Companies producing more than the approved amount would be sanctioned. This put additional pressure on miners, especially those that used debt extensively. These companies were hoping to cope with declining margins by producing more to recover the cost of their infrastructure, but the government's action made it difficult. At the same time, the government was proposing an increase in coal royalties and imposing a windfall profits tax in case coal prices were to increase dramatically. All these actions further decreased miners' profit margins, especially those of small producers with low-quality coal. In addition, China was trying to ban the import of low-grade coal that would greatly affect the small producers' exports to China. Unlike larger miners who could blend higher- and lower-quality coal to meet the Chinese requirement, small producers didn't have the financial resources to do so. All these risks were compounded by the condemnation by Greenpeace that coal mining was destabilizing the Indonesian economy, diminishing livelihoods, and exacerbating poverty. The Investment Proposal Agus Halim invited his finance manager to discuss the acquisition plan with him. They thought the proposed purchase price of the mine was reasonable. The mine-verified mineable surface reserves were of medium quality, and were estimated at 12 million tons. Agus figured they could easily produce at least one million tons from this mine per year. The finance manager estimated that including the mine purchase price, the capital expenditure needed to get production started would be about US$30 million, with US$15 million outlay immediately after the deal was closed, and another US$15 million a year after. The working capital investment was estimated to be an additional $2.5 million a year starting in 2015. Besides capital costs, there were also coal-mining expenses including employee-related costs, internal and external coal transportation costs, blasting, drilling, and other mining-related costs. Additionally, there were expenses related to ash disposal. The finance manager estimated that operating expenses would total US$25 per ton, and would increase at a rate of 5% per year. To determine if the investment would create value for the firm, the finance manager needed to first esti- mate the weighted cost of capital (WACC) for this investment. WACC is calculated by weighting cost of debt and cost of equity, with the proportion of capital in debt (D/CD+E)) and the proportion of capital in equity (E/(D+E)), respectively. D E WACC = {( -*) C )*(1-1)*;}+{( *';} D+E D+E o = cost of debt 1 - cost of equity D = value of debt E = value of equity T = corporate tax rate The finance manager figured he could get the bank to finance $12 million of the capital cost with a 10-year term loan at 14% annual interest rate, completely drawn down in 2015. The other $18 million plus $2.5 mil- lion working capital investment would come from cash in hand and equity injection from the parent firm. To estimate the cost of equity, also called the required rate of return for the owners, the finance manager believed the best way was to use the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). CAPM stipulates that the required rate of return for the equity holders for this investment varies in direct proportion with the systematic risk called beta (B). T = R + B.(R-R) r = cost of equity R = current government benchmark interest rate B. = beta of the investment R-R = equity risk premium The beta for coal mining companies was estimated to be 1.4, and the equity risk premium for projects in Indonesia was 8.8%.' The most recent government benchmark interest rate was 7.5% (see Exhibit 5). The In- donesian stock market performance, the Indonesian rupiah and U.S. dollar exchange rates, and the Indonesian inflation rates are presented in Exhibits 6, 7, and 8, respectively. The finance manager also prepared the cash flow forecasts for this investment based on the prevailing Indonesia corporate tax rate of 25%, shown in Exhibit 9. How attractive was this investment? With the recent coal prices dropped to a level lower than those dur- ing the global financial crisis, do you think it is a good time to pursue expansion of coal mining? Would Agus Halim be able to get the green light from the parent firm to pursue it? Would the bankers grant the $12 million term loan for this acquisition? Exhibit 9. Cash Flow Forecasts for the Proposed Investment Projected Financials of Coal Mining Expansion Proposal (in thousands of US$ unless stated) Forecasted Coal Prices and volumes 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 2026 Coal Price (US$/ton) Operating Expenses (USS/ton)-5% increase New Mine Production (thousands of tons) 45 25 45 26 45 28 1,000 50 29 1,000 50 30 1,000 50 32 1,000 50 34 1,000 60 35 1,000 60 37 1,000 60 39 1,000 60 41 1,000 60 43 1,000 Projected Revenue and Costs Projected Revenue Royalties (13.5%) Operating Expenses Depreciation (US$30m/10 years) Pre-tax Operating Profit Taxes (25%) After-tax Operating Profit 45,000 (6,075) (27,563) (3,000) 8,363 (2,091) 6,272 50,000 (6,750) (28,9411 (3,000) 11,309 (2,8271 8,482 50,000 (6,750) (30,388) (3,000) 9,862 (2,466) 7,397 50,000 (6,750) (31,907) (3.000) 8,343 (2,086) 6,257 50,000 (6,750) (33,502) (3,000) 6,748 (1,687) 5,061 60,000 (8,100) (35,1781 (3,000) 13,722 (3,431) 10,292 60,000 (8,100) (36,936) (3,000) 11,964 (2,991) 8,973 60,000 (8,100) (38,783) (3,000) 10,117 (2,529) 7,588 60,000 (8,100) (40,722) (3,000) 8,178 (2,044) 6,133 60,000 (8,100) (42,758) (3,000) 6,142 (1,535) 4,606 Projected Non-Operating Cash Flows (15,000) Capital Costs Working Capital Investment (15,000) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) Diamond Energy Resources It was December 2015; Mr. Agus Halim, the CEO of PT Diamond Energy Resources Indonesia, had just finished reviewing a preliminary acquisition plan prepared by his consultant. He was excited about the opportunity to expand Diamond's coal mining capacity by acquiring a new mine near East Kalimantan. This acquisition would significantly increase Diamond's verified mineable surface coal reserves, and position it as an important player in the coal export market. However, before doing so, Agus needed to ensure that this investment would create value for the firm. Then he needed to get the green light from his parent firm and convince his local banker to provide the necessary financing. Company Background PT Diamond Energy Resources Indonesia, a wholly owned subsidiary of Australian-based Diamond Energy Inc., was established in 2005 to conduct coal mining business in Indonesia. It owned six mines, mainly in the surrounding areas of Central and East Kalimantan, with a combined 4,700 hectares of coal mining concession area and an estimated 40 million tons of coal reserves. It produced approximately 2 million metric tons of coal per year, 80% of which were medium-grade coals with a calorific value of 6,100 cal/g; the other 20% were low grade, with a calorific value of around 3,700 cal/g. The company operated under strict guidelines, conforming to all health and environmental safety standards. It aimed to continuously improve via quality management systems, minimizing occupational hazards and environmental impact, and saving energy and other resources. Its coal production was mainly sold to domestic and international companies such as Glencore, INCO, and Trafigura. Since its incorporation, the company had enjoyed moderate financial success, with operating margins and return on invested capital averaging 21% and 16% in the last five years, respectively. As seen in Exhibit 2, its sales volume (in tons) increased every year from 2010-2015, even though revenue experienced a decline in 2013 and 2014 due to the decline in coal prices. Compared to other companies in the industry, illustrated in Exhibit 3, Diamond was a very small player. However, its operating margin in 2014 was better than most. The debt-to-capital ratios for the industry players vary widely, from 0% to 148% (due to negative equity in a couple of companies). Diamond's ratio of 44% was lower than all but three companies, and was slightly below the average of 59%. The Coal Industry in Indonesia Coal is an important source of energy used to generate about 41% of the world's electricity and produce 70% of the world's steel. Indonesia is one of the largest producers of coal in the world with coal reserves estimated to last approximately another 83 years if the current rate of production were to continue. While there are many smaller pockets of coal reserves spreading across the islands of Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua, most of the coal reserves in Indonesia are in South Sumatra, East and South Kalimantan. The industry is very fragmented with a few large players such as Adaro Energy and Bumi Resources, and a large number of small miners. Since about 70-80% of the production is exported, Indonesia is now the world's largest exporter of thermal coal, exporting a total of 382 million metric tons in 2014 (see Exhibit 4). A significant amount of its exported thermal coal was of medium to low quality, selling mainly to India and China. While coal-mining companies in Indonesia had generally fared well, the risks, especially to small miners, were not insignificant. The decline in coal prices in the last few years had resulted in the clo- sure of some small producers in Indonesia. (For example, by the end of 2012, nearly 90% of the coal mines in Indonesia's Jambi province had to close.) To stem the declining coal prices, Indonesia's gov- ernment tried to limit total coal production in 2014 to a level about 5% lower than that in 2013. a Companies producing more than the approved amount would be sanctioned. This put additional pressure on miners, especially those that used debt extensively. These companies were hoping to cope with declining margins by producing more to recover the cost of their infrastructure, but the government's action made it difficult. At the same time, the government was proposing an increase in coal royalties and imposing a windfall profits tax in case coal prices were to increase dramatically. All these actions further decreased miners' profit margins, especially those of small producers with low-quality coal. In addition, China was trying to ban the import of low-grade coal that would greatly affect the small producers' exports to China. Unlike larger miners who could blend higher- and lower-quality coal to meet the Chinese requirement, small producers didn't have the financial resources to do so. All these risks were compounded by the condemnation by Greenpeace that coal mining was destabilizing the Indonesian economy, diminishing livelihoods, and exacerbating poverty. The Investment Proposal Agus Halim invited his finance manager to discuss the acquisition plan with him. They thought the proposed purchase price of the mine was reasonable. The mine-verified mineable surface reserves were of medium quality, and were estimated at 12 million tons. Agus figured they could easily produce at least one million tons from this mine per year. The finance manager estimated that including the mine purchase price, the capital expenditure needed to get production started would be about US$30 million, with US$15 million outlay immediately after the deal was closed, and another US$15 million a year after. The working capital investment was estimated to be an additional $2.5 million a year starting in 2015. Besides capital costs, there were also coal-mining expenses including employee-related costs, internal and external coal transportation costs, blasting, drilling, and other mining-related costs. Additionally, there were expenses related to ash disposal. The finance manager estimated that operating expenses would total US$25 per ton, and would increase at a rate of 5% per year. To determine if the investment would create value for the firm, the finance manager needed to first esti- mate the weighted cost of capital (WACC) for this investment. WACC is calculated by weighting cost of debt and cost of equity, with the proportion of capital in debt (D/CD+E)) and the proportion of capital in equity (E/(D+E)), respectively. D E WACC = {( -*) C )*(1-1)*;}+{( *';} D+E D+E o = cost of debt 1 - cost of equity D = value of debt E = value of equity T = corporate tax rate The finance manager figured he could get the bank to finance $12 million of the capital cost with a 10-year term loan at 14% annual interest rate, completely drawn down in 2015. The other $18 million plus $2.5 mil- lion working capital investment would come from cash in hand and equity injection from the parent firm. To estimate the cost of equity, also called the required rate of return for the owners, the finance manager believed the best way was to use the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). CAPM stipulates that the required rate of return for the equity holders for this investment varies in direct proportion with the systematic risk called beta (B). T = R + B.(R-R) r = cost of equity R = current government benchmark interest rate B. = beta of the investment R-R = equity risk premium The beta for coal mining companies was estimated to be 1.4, and the equity risk premium for projects in Indonesia was 8.8%.' The most recent government benchmark interest rate was 7.5% (see Exhibit 5). The In- donesian stock market performance, the Indonesian rupiah and U.S. dollar exchange rates, and the Indonesian inflation rates are presented in Exhibits 6, 7, and 8, respectively. The finance manager also prepared the cash flow forecasts for this investment based on the prevailing Indonesia corporate tax rate of 25%, shown in Exhibit 9. How attractive was this investment? With the recent coal prices dropped to a level lower than those dur- ing the global financial crisis, do you think it is a good time to pursue expansion of coal mining? Would Agus Halim be able to get the green light from the parent firm to pursue it? Would the bankers grant the $12 million term loan for this acquisition? Exhibit 9. Cash Flow Forecasts for the Proposed Investment Projected Financials of Coal Mining Expansion Proposal (in thousands of US$ unless stated) Forecasted Coal Prices and volumes 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 2026 Coal Price (US$/ton) Operating Expenses (USS/ton)-5% increase New Mine Production (thousands of tons) 45 25 45 26 45 28 1,000 50 29 1,000 50 30 1,000 50 32 1,000 50 34 1,000 60 35 1,000 60 37 1,000 60 39 1,000 60 41 1,000 60 43 1,000 Projected Revenue and Costs Projected Revenue Royalties (13.5%) Operating Expenses Depreciation (US$30m/10 years) Pre-tax Operating Profit Taxes (25%) After-tax Operating Profit 45,000 (6,075) (27,563) (3,000) 8,363 (2,091) 6,272 50,000 (6,750) (28,9411 (3,000) 11,309 (2,8271 8,482 50,000 (6,750) (30,388) (3,000) 9,862 (2,466) 7,397 50,000 (6,750) (31,907) (3.000) 8,343 (2,086) 6,257 50,000 (6,750) (33,502) (3,000) 6,748 (1,687) 5,061 60,000 (8,100) (35,1781 (3,000) 13,722 (3,431) 10,292 60,000 (8,100) (36,936) (3,000) 11,964 (2,991) 8,973 60,000 (8,100) (38,783) (3,000) 10,117 (2,529) 7,588 60,000 (8,100) (40,722) (3,000) 8,178 (2,044) 6,133 60,000 (8,100) (42,758) (3,000) 6,142 (1,535) 4,606 Projected Non-Operating Cash Flows (15,000) Capital Costs Working Capital Investment (15,000) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) (2,500)Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started