Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

QUESTION: Estimate an appropriate cost of capital to use in valuing the teak plantation investment. Please be sure to include a discussion of how you

QUESTION:

Estimate an appropriate cost of capital to use in valuing the teak plantation investment. Please be sure to include a discussion of how you propose to adjust your cost of capital estimate for political and otherrisks.

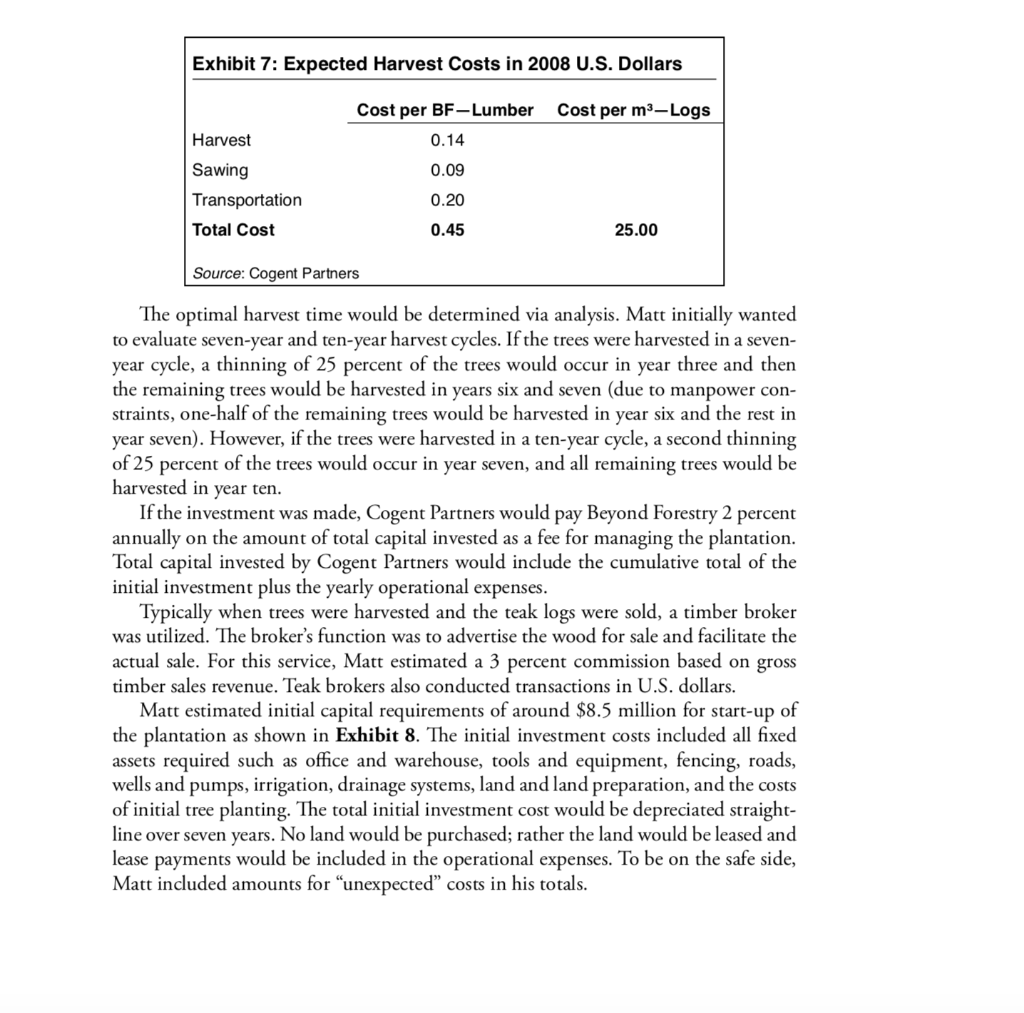

Given the many risks associated with this investment, it is difficult to accurately reflect the risk inthe cost of capital estimate. What other approaches could be used to evaluate the investment and assess itsrisk?

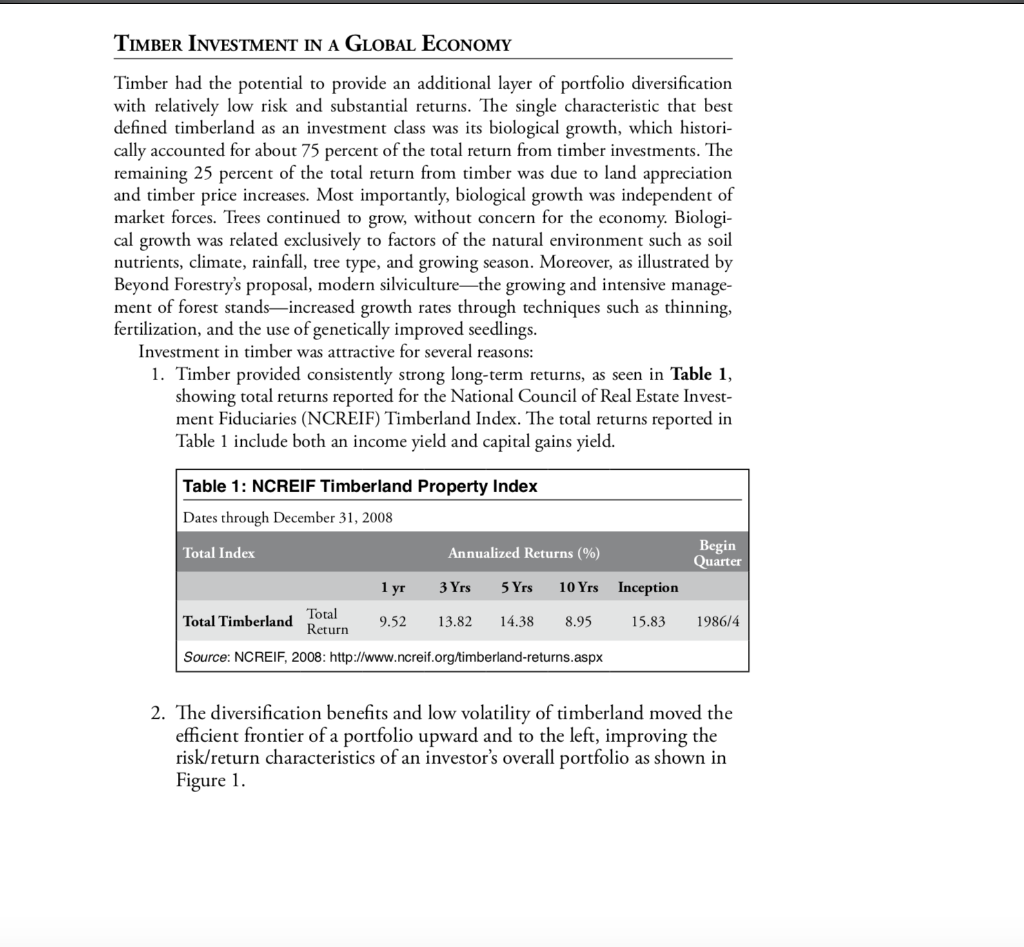

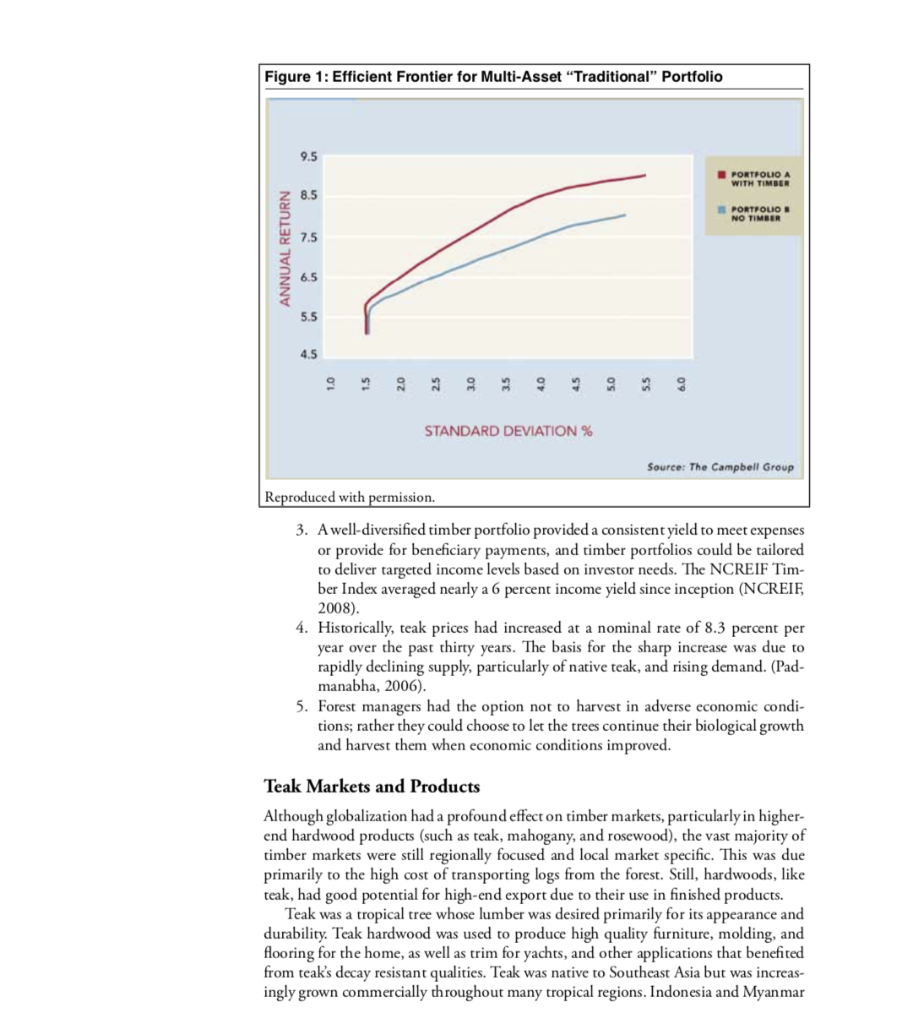

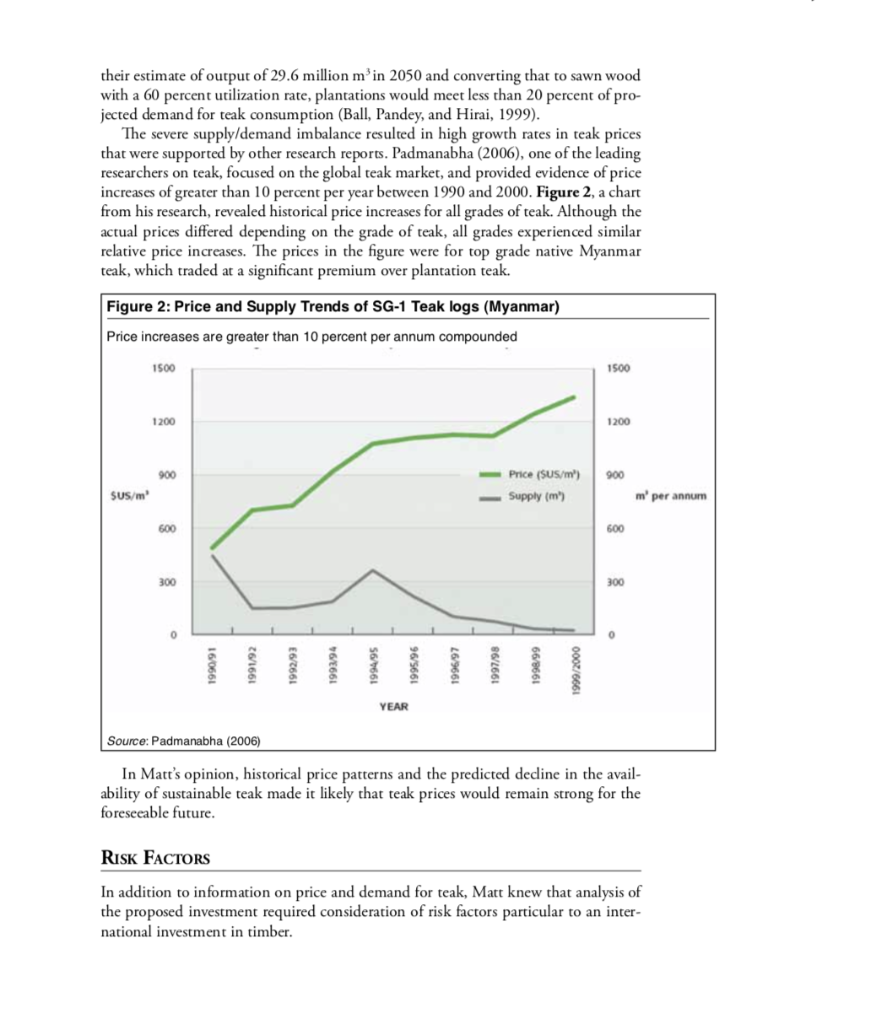

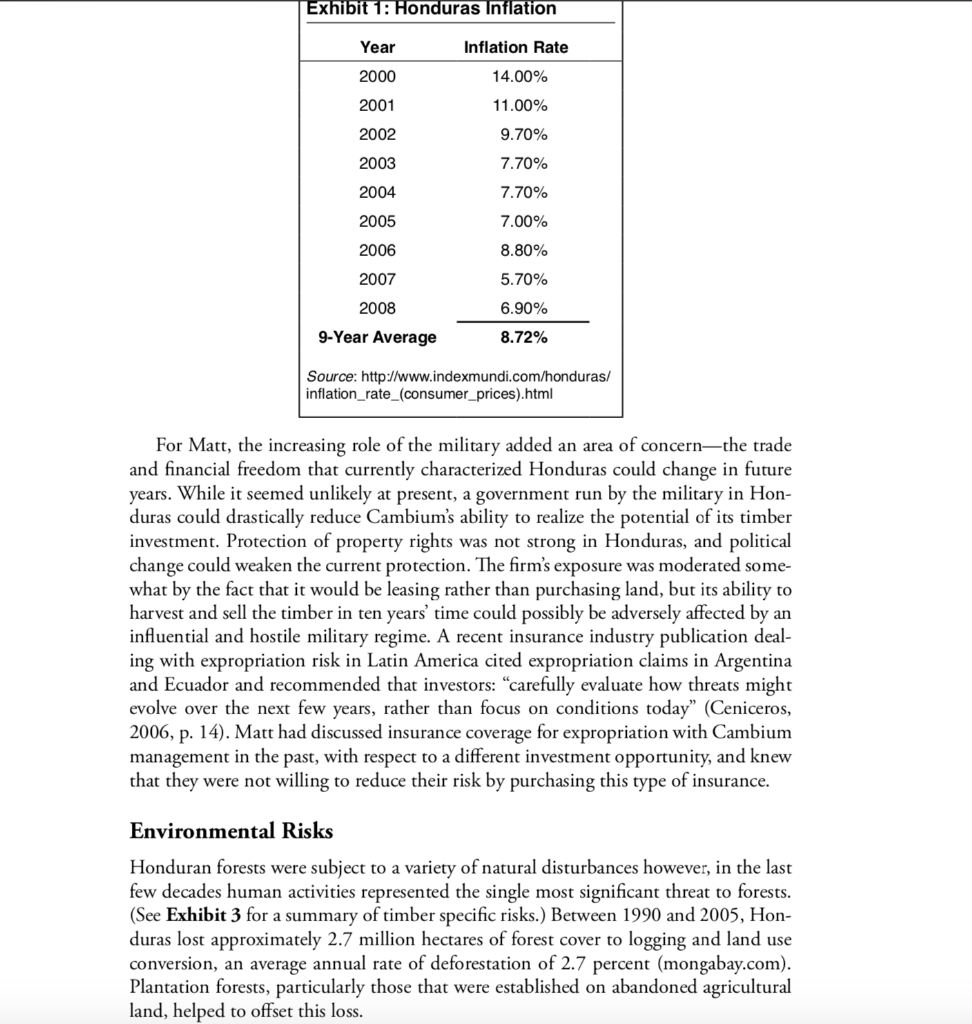

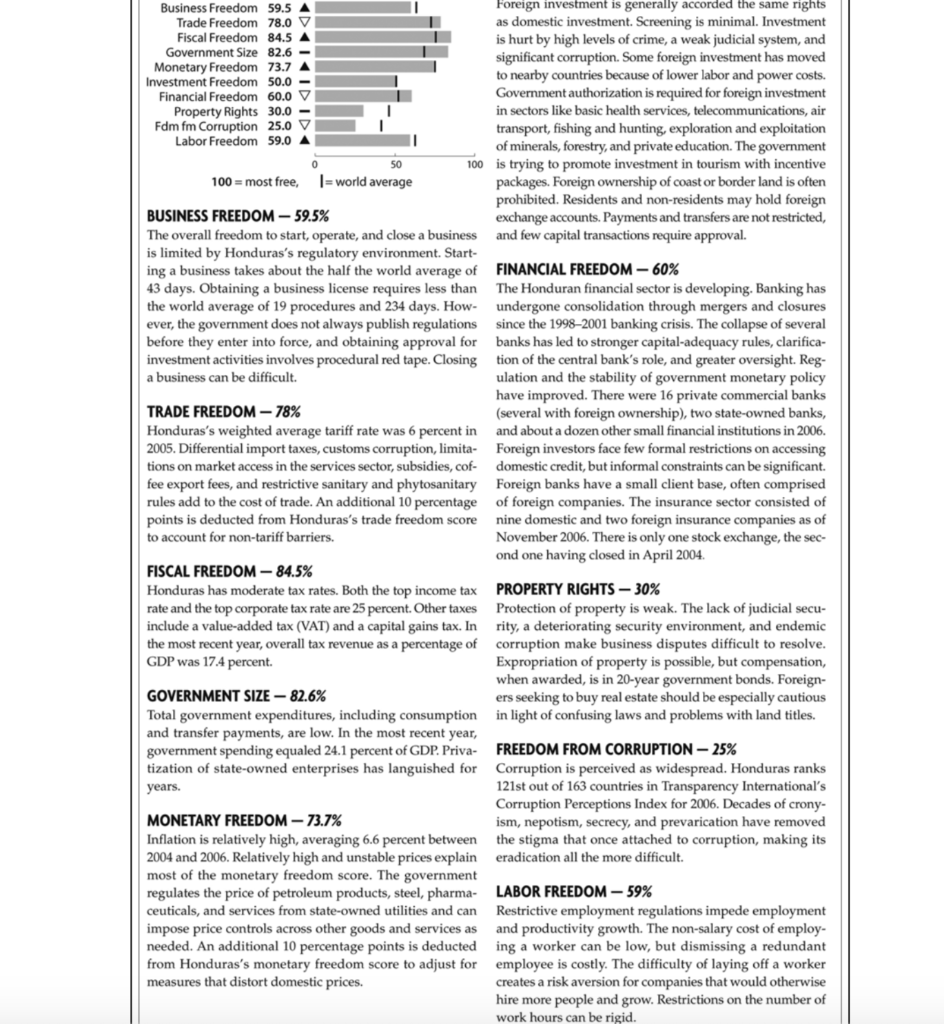

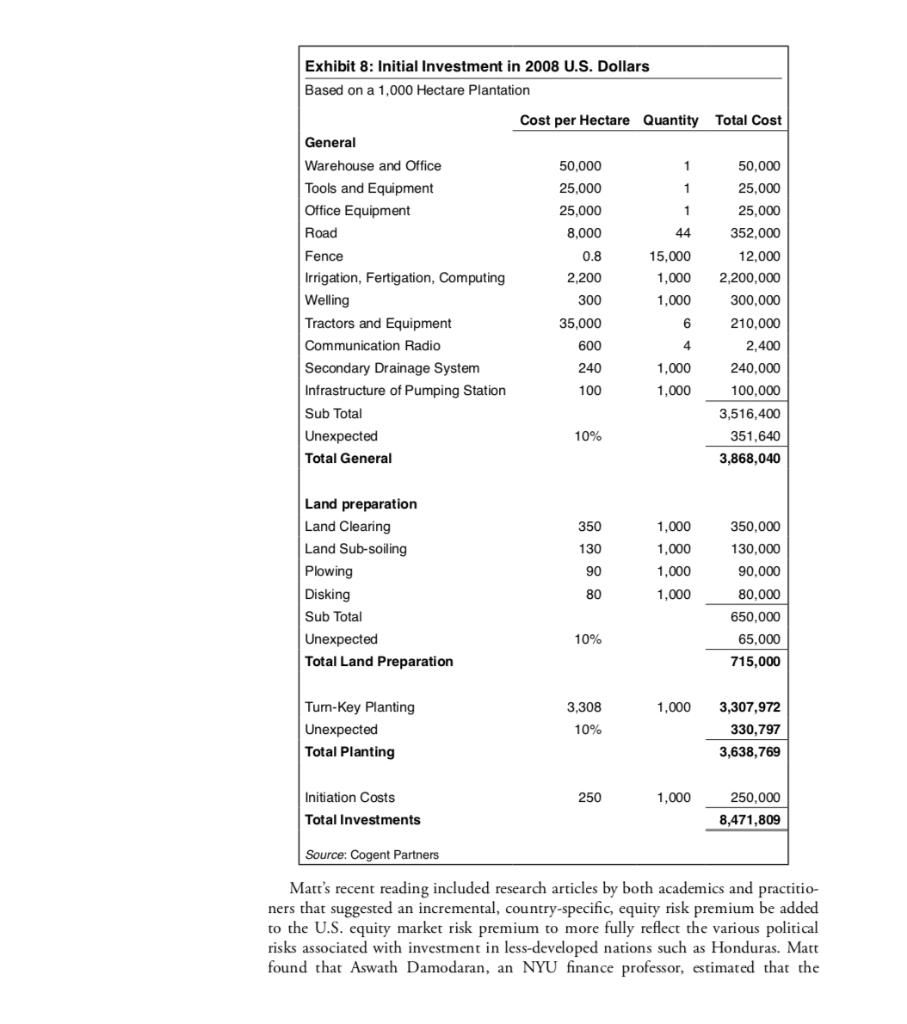

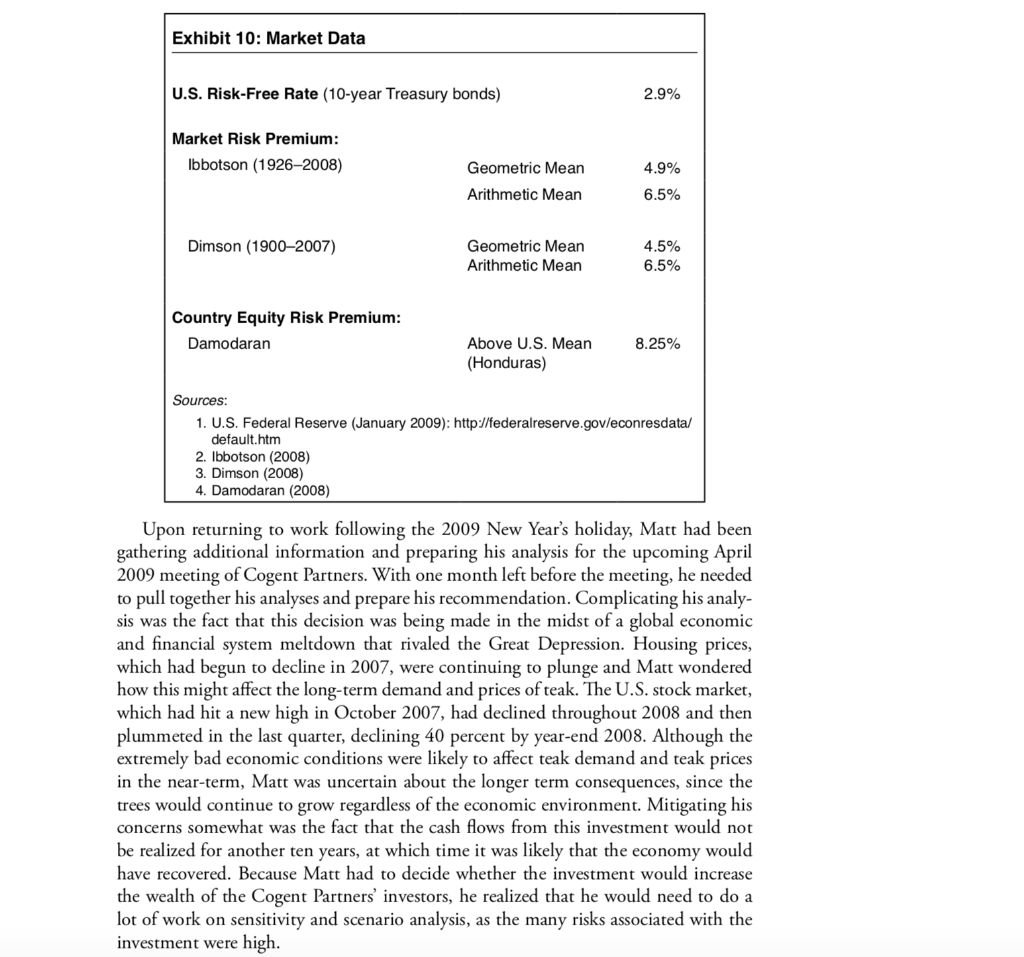

An Investment Analysis of Honduran Teak Plantations Lisa Majure, Northern Arizona University Kathryn Savage, Northern Arizona University Matthew Haertzen, Northern Arizona University Alex Finkral, The Forestland Group n March of 2009, Matthew Haertzen, a timber portfolio manager for Cogent Part- ners, was in the midst of his evaluation of an intriguing investment proposal from .Beyond Forestry, a Honduran company that managed teak plantations in Hon- duras. Beyond Forestry employed a unique accelerated teak growth model that used advanced-stage cloned planting stock and intensive forest management in a tropical climate well-suited for the growth of teak. This accelerated growth model allowed for harvesting of teak timber in as few as seven years, compared to 20-30 years for tradi- tional commercial plantations. Currently, Beyond Forestry operates five trial teak plan- tations in Honduras, owned by Honduran business professionals. The company was seeking investors to provide capital to initiate and run a sixth teak plantation. It con- tacted Cogent Partners, the fund managers for Cambium Global Timberland (Ticker: TREE), a UK listed timber investment fund, to see if they would be interested. As portfolio manager, Matt needed to analyze this opportunity from a financial perspective. While he recognized the economic potential of the new growth model, he was also aware of the non-economic factors that might increase the risk of this invest- ment, and the need to factor those into his analysis. The quarterly meeting of Cogent Partners would be held in April 2009, and he needed to determine if the proposed investment was a value-added addition to the Cogent Partners' portfolio. Matt was a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) and an expert in timber investment Prior to working for Cogent Partners, he was the Chief Investment Officer, responsible for the management of both $1.2 billion in financial assets of the Idaho Endowment Investment Board and the $2 billion Idaho real asset portfolio, comprised 90 percent of timberland. His educational background included a BA in economics and an MBA in finance and strategic management TRIP TO HONDURAS Matt was fascinated with the proposal from Beyond Forestry because it claimed that the company's plantations could allow for a very short harvest cycle relative to norms in the teak industry. He knew that natural teak forests generally used a 70-80 year ASso ciation,n harvest cycle, whereas managed teak plantations typically harvested in a 20-30 year cycle. Since Beyond Forestry was claiming to harvest the teak in as few as seven years, Matt initially was quite skeptical of the investment proposal. Controversy had been generated in several countries (primarily in Costa Rica, India, and Mexico) by the pro- motion of teak plantation investment schemes. These schemes used false growth and harvest yield projections, unrealistic pricing scenarios, and dubious fund management strategies to attract investors. "The long time horizons and broad range of price predic- tions associated with teak plantation investment provided opportunities for dishonest entrepreneurs to exaggerate figures and deceive even moderately wary investors." (Pan- dey and Brown, 2006). Additionally, since Beyond Forestry was a start-up company, no financial history of its operations was available for Matt to analyze. Due to these concerns about the potential investment, Matt decided that it would be necessary to visit the existing Honduran plantations to verify the growth and yield data that were presented in Beyond Forestry's investment proposal. Also, due to the lack of financial data for Beyond Forestry, Matt would need to meet with trial plan- tation managers to estimate all of the costs of start-up and operations. In addition to planning the trip, Matt enlisted the help of his colleague, Alex Finkral, a forestry professor, to assist in the assessment of the teak tree growth rates at Beyond Forestry's plantations Matt and Alex visited Honduras in early December 2008. After two days of inten- sive, on-the-ground review of three of Beyond Forestry's plantations, they were able to confirm the rapid growth rates reported in the information that was provided by Beyond Forestry. As part of their investigation, Matt and Alex walked fields to observe irrigation, tree spacing, and general management practices. In addition, the two men marked off sampling plots and took independent measurements to verify the reported growth data. As Matt spoke with his Honduran contacts he learned that the rapid growth of Beyond Forestry's plantations was due to many factors, one of which was the use of cloned seedlings. The growth of Beyond Forestry's seedlings began in the laboratories of Galiltec, a company with demonstrated expertise and experience in developing tissue culture plants for commercial food growing applications. Galiltec's seedlings were the genetic progeny of twenty-five mature Honduran teak trees. In a six-month process, seedlings were cloned in tissue culture, raised in individual contain ers in greenhouses, and outplanted to the field. Beyond Forestry's growth results were also due to the intensive management of its plantations using appropriate irrigation systems, fertilizers, fungicides, pruning, and thinning. Other existing teak plantations typically did not employ modern silvicultural (intensive plantation management) techniques. At the time of his trip, Beyond Forestry had five trial plantations with trees ranging in age from eight to forty-four months Upon their return from Honduras, Matt and Alex performed additional calcula- tions to verify growth rates and net volume projections, and then Matt focused on learning as much as he could about global timber markets in general, the country of Honduras, and the teak wood market specifically Figure 1: Efficient Frontier for Multi-Asset "Traditional" Portfolio 9.5 PORTFOLIO A WITH TIMBER 8.5 PORTFOLIO 7.5 6.5 5.5 4.5 10 20 25 STANDARD DEVIATION % Source: The Campbell Group Reproduced with permission. 3. Awell-diversified timber portfolio provided a consistent yield to meet expenses or provide for beneficiary payments, and timber portfolios could be tailored to deliver targeted income levels based on investor needs. The NCREIF Tim- ber Index averaged nearly a 6 percent income yield since inception (NCREIF, 2008) 4. Historically, teak prices had increased at a nominal rate of 8.3 percent per year over the past thirty years. The basis for the sharp increase was due to rapidly declining supply, particularly of native teak, and rising demand. (Pad manabha, 2006). 5. Forest managers had the option not to harvest in adverse economic condi- tions; rather they could choose to let the trees continue their biological growth and harvest them when economic conditions improved. Teak Markets and Products Although globalization had a profound effect on timber markets, particularly in higher- end hardwood products (such as teak, mahogany, and rosewood), the vast majority of timber markets were still regionally focused and local market specific. This was due primarily to the high cost of transporting logs teak, had good potential for high-end export due to their use in finished products Teak was a tropical tree whose lumber was desired primarily for its appearance and duability. Teak hardwood was used to produce high quality furniture, molding, and looring for the home, as well as trim for yachts, and other applications that benefited from teak's decay resistant qualities. Teak was native to Southeast Asia but was increas- ingly grown commercially throughout many tropical regions. Indonesia and Myanmar the est. Still, hardwoods, like ANNUAL RETURN were the largest producers and exporters of teak. Teak had been planted successfully beyond its native range for more than 100 years and was commonly found in com- mercial plantations in Latin American countries, growing in relatively short rotation (20-30 years). Historically, the largest manufacturers of teak products were found in Indonesia, China, Thailand, and India. Honduran Teak: Economic Value and Wood Quality In general, the sales price charged for teak logs was based on size and form. Teak grown in natural forests commanded higher prices than teak grown in plantations. Data for plantation grown teak logs was available, but limited. Beyond that, larger straight logs without branch wounds (knots) were more valuable than smaller, less straight logs (Keogh, 2008). Larger logs contained a higher percentage of heartwood volume (desirable for its appearance and decay resistant properties) proportional to total log volume than small diameter logs (Percz, Cordero, and Kanninen, 2003). Matt knew that there was no standard grading system for teak and that the variance in price was enormous, in part depending on the amount of heartwood in the tree. An old growth 100-year-old tree could have a price more than six times that of a plantation raised tree, based primarily on the heartwood formation in the very mature trees. For the proposed investment, a specific concern stemmed from the effect of the proposed short harvest cycle on the market price of the teak that would be produced. The accelerated growth techniques used by Beyond Forestry resulted in growth so fast that it was hard to predict the amount of heartwood in the tree Several studies had investigated the effect of intensive plantation practices such as rapid growth, and silvicultural thinning on teak wood quality and stem form (Bhat, 2000a; Bhat, 2000b; Perez and Kanninen, 2005). It appeared that there was no con- dusive evidence that wood quality was affected significantly by plantation practices similar to those of Beyond Forestry. Faster growth and short rotations appeared to have little effect on the strength and specific gravity of teak wood (Bhat, 2000b). In 2006, Beyond Forestry commissioned a study of the workability properties of the teak logs from the first plantation thinnings (Fundacion Cuprofor, 2006). Consistent with other research, the study found that the wood from the small logs was suitable for the manufacture of a wide range of products. Additionally, the characteristics of Beyond Forestry's rapidly grown teak were within the range of "normal" plantation teak Available price data for teak logs grown in Central and South American plantations suggested a "normal" range between U.S. $200/m3 and $300/m3 for small diameter logs, with prices as high as U.S. $500/m3 on record (DeCamino et al., 2002; ITTO, 2006-2007; Keogh, 2008). These small diameters (approximately 15-20 centimeters) had been achieved in Beyond Forestry plantations after three to four years of growth. GLOBAL SUPPLY AND DEMand FOR TEAK Given the sensitivity of the investment to teak pricing, a deeper analysis of the teak market was needed. It quickly became clear that despite them both being called teak, there really were two distinct products in the marketplace. The first was native teak which was often harvested at ages ranging from 80-100 years. The second was planta- tion teak which was harvested at much younger ages (20-25 years in most cases). Native Teak Native (or natural) teak forests existed in only a small number of countries: India, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, Myanmar, and Thailand. Teak was also naturalized in Indonesia, where it was introduced several hundred years ago (Pandey and Brown 2000). During the last twenty years most supplies of teak from natural forests had dwindled. In general, land available for timber production was in a state of decline. Working forests were removed from production as land was sold for alternative uses. In some regions, environmental conservation efforts increasingly restricted the harvest of native teak forests, particularly on publicly owned lands. Significant restrictions had been instituted in several countries. Thailand, India, and Lao People's Democratic Republic banned the harvesting of natural teak forests. Other countries, Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Ghana had all banned teak wood exports. As teak resources declined, the product's value increased Research by Padmanabha (2006) and Gyi and Tint (1998) reported an evaluation of natural teak forests as follows: 1. India (8.9 million hectares): Teak harvest from India's forests was banned in 1997. After that time, fully 100 percent of teak logs used in India were imported (approximately 2.5 million m3). African countries have supplied the majority of Indian teak logs over the past fifteen years, but diminishing supply has driven India to import young teak from Latin America 2. Thailand (2.5 million hectares): All teak harvest was banned in Thailand in 1989 3. Myanmar (16.5 million hectares): Myanmar was the only remaining country in the world supplying native teak. There was clear evidence that the native forests still being harvested were not being done so in a sustainable fashion Significant illegal harvest also continued in Myanmar. 4. Laos (16,000 hectares): The native forests in Laos were too small to provide meaningful levels of teak production. These significant harvesting restrictions had led to sharp increases in prices for natural teak, leading to increased substitution of plantation teak. In addition, the lack of sustainably managed native forests had led many socially responsible buyers to elim- nate their purchases of native teak even where supply was available Research on native teak led Matt to believe that the decline in available product, coupled with the growing global focus on environmentally sustainable wood sources, would lead to increased adoption of plantation teak on a global basis. Additionally native teak was used for high-end products that would not compete directly with the more conventional uses of plantation teak including patio furniture, decking, and other exterior uses where teak's decay resistant qualities were so critical. Plantation Teak The growth and other tropical hardwood, due to its having been grown on a commercial scale for more than 150 years in over fifty different tropical countries. According to Pandey and Brown (2000), 75 percent of current teak plantations were in India and Indonesia. Determining future teak supply from these plantations was difficult due to uncertainty as to specific growth rates, and site quality. However in 1999, Ball, Pandey, and Hirai used a probability model with several specific adjustments to develop estimates. Using lopment teak in plantations was better understood any their estimate of output of 29.6 million m in 2050 and converting that to sawn wood with a 60 percent utilization rate, plantations would meet less than 20 percent of pro jected demand for teak consumption (Ball, Pandey, and Hirai, 1999). The severe supply/demand imbalance resulted in high growth rates in teak prices that were supported by other research reports. Padmanabha (2006), one of the leading researchers on teak, focused on the global teak market, and provided evidence of price increases of greater than 10 percent per year between 1990 and 2000. Figure 2, a chart from his research, revealed historical price increases for all grades of teak. Although the actual prices differed depending on the grade of teak, all grades experienced similar relative price increases. The prices in the figure were for top grade native Myanmar teak, which traded at a significant premium over plantation teak Figure 2: Price and Supply Tre nds of SG-1 Teak logs (Myanmar) Price increases are greater than 10 percent per annum compounded 1500 1500 1200 1200 Price (SUS/m) 900 900 SUS/m m' per annum Supply (m) 600 600 300 300 YEAR Source: Padmanabha (2006) In Matt's opinion, historical price patterns and the predicted decline in the avail ability of sustainable teak made it likely that teak prices would remain strong for the foreseeable future RISK FACTORS In addition to information on price and demand for teak, Matt knew that analysis of the proposed investment required consideration of risk factors particular to an inter national investment in timber. 1999/2000 66966 96/L661 L6/9661 1995/96 56h661 1993/94 E6/7661 26/1661 16/0661 Exhibit 1: Honduras Inflation Year Inflation Rate 2000 14.00% 2001 11.00% 2002 9.70% 2003 7.70% 2004 7.70% 2005 7.00% 2006 8.80% 2007 5.70% 2008 6.90% 9-Year Average 8.72% Source: http://www.indexmundi.com/honduras/ inflation_rate_(consumer_prices).html For Matt, the increasing role of the military added an area of concern-the trade and financial freedom that currently characterized Honduras could change in future years. While it seemed unlikely at present, a government run by the military in Hon- duras could drastically reduce Cambium's ability to realize the potential of its timber investment. Protection of property rights was not strong in Honduras, and political change could weaken the current protection. The firm's exposure was moderated some- what by the fact that it would be leasing rather than purchasing land, but its ability to harvest and sell the timber in ten years' time could possibly be adversely affected by an influential and hostile military regime. A recent insurance industry publication deal- ing with expropriation risk in Latin America cited expropriation claims in Argentina and Ecuador and recommended that investors: "carefully evaluate how threats might evolve over the next few years, rather than focus on conditions today" (Ceniceros 2006, p. 14). Matt had discussed insurance coverage for expropriation with Cambium management in the past, with respect to a different investment opportunity, and knew that they were not willing to reduce their risk by purchasing this type of insurance Environmental Risks Honduran forests were subject to a variety of natural disturbances however, in the last few decades human activities represented the single most significant threat to forests (See Exhibit 3 for a summary of timber specific risks.) Between 1990 and 2005, Hon- duras lost approximately 2.7 million hectares of forest cover to logging and land use conversion, an average annual rate of deforestation of 2.7 percent (mongabay.com). Plantation forests, particularly those that were established on abandoned agricultural land, helped to offset this loss. Exhibit 3. Timber Specific Ris ks Mitigation Risk Site Selection Fire Ongoing Maintenance (fuels reduction) On Site Monitoring Site Selection Wind Tree Age Site Selection Proper Drainage Floods Active Management Aggressive Containment Insects/Disease Site Selection Timber Theft On Site Monitoring Evaluation of Local Markets Pricing Long-Term Supply Agreements Expertise in Physical Commodity Trading Natural disturbances that affected forests in Honduras included hurricanes (and and associated flooding) and in mountain ous areas, landslides. The destructive winds extraordinary levels of precipitation from a hurricane posed significant threats to forest plantations. The proposed site of the Beyond Forestry plantation was near the city of San Pedro Sula in the country's northwest corner and thirty kilometers inland from the coast. Given its distance from the Caribbean co ast, San Pedro Sula was less vulnerable than the coastal regions to the most devastating effects of hurricanes. Nonetheless, flood- ing could occur inland, and flood probability was a consideration in selecting plantation sites. Landslides also occurred in the more mountainous areas of Honduras, but since the Beyond Forestry site was abandoned farmland, the risk of landslide was minimal. The most important potential insect pest for teak in Honduras was the "teak defo- liator" moth (Hyblaea puera), a defoliating insect that occurred worldwide. Despite the presence of Hyblaea puera in Honduras on other plant species, there were no reports that it had occurred in teak plantations (Nair, 2001). Similarly, there were no reported accounts of economic effects in Honduras due to other insects that invade teak for- ests worldwide. Teak was grown in Panama for more than thirty years without prob- lems from insect infestation (United Nature, 2008). Furthermore, Beyond Forestry's proposed model reduced exposure to insect damage through short rotations. Even in a worst case scenario-full defoliation of a plantation-the timber would likely still be merchantable 33cm logs $303.50 10/1/2007 Costa Rica Costa Rica $275.00 33cm logs 3/16/2007 35+ cm logs 10/1/2007 Costa Rica $320.00 11/16/2007 $335.00 38cm logs Panama 11/16/2007 42+ cm logs $365.00 $319.70 Panama Source: ITTO (International Tropical Timber Organization) (Bi-monthly Reports 2006-2007 various) http://www.itto.int/mis_back_issues/ Exhibit 6: Operational Expenses per 1000 Hectares in 2008 U.S. Dollars Yearly Cost Unit Manager 126,000 Field Managers 210,000 Field Workers 512,400 280,000 Guards Vehicle Expenses 73,000 Fuel & Lubricants 71,000 Equipment Maintenance 75,000 Fertilizers 250,000 Fungicides/Pesticides 65,000 Weed Control 70,000 Water including Energy 300,000 Land Lease 367,500 2,399.900 Total Unexpected Costs at 10% 239.990 Total Annual Cost 2,639,890 Source: Cogent Partners The estimated costs of harvesting the teak, including the costs of felling and transporting the logs, were estimated as shown in Exhibit 7. These costs also would need to be adjusted for Honduran inflation. Harvest costs were incurred whenever plantation thinning was per- formed and during any period when teak was harvested. Thinning was necessary to maintain the health of the remaining trees and to ensure that they had sufficient sunlight and room to grow. Typically 25 percent of the existing trees were removed in the thinning phase, which generally occurred in year three and again in year seven. Since the remaining trees continued to grow, they became more valuable with age due to their increased size and volume Exhibit 7: Expected Harvest Costs in 2008 U.S. Dollars Cost per BF-Lumber Cost per m3-Logs Harvest 0.14 Sawing 0.09 Transportation 0.20 Total Cost 0.45 25.00 Source: Cogent Partners The optimal harvest time would be determined via analysis. Matt initially wanted to evaluate seven-year and ten-year harvest cycles. If the trees were harvested in a seven- year cycle, a thinning of 25 percent of the trees would occur in year three and then the remaining trees would be harvested in years six and seven (due to manpower con straints, one-half of the remaining trees would be harvested in year six and the rest in year seven). However, if the trees were harvested in a ten-year cycle, a second thinning of percent of the trees would occur in year seven, and all remaining trees wou harvested in year ten If the investment was made, Cogent Partners would pay Beyond Forestry 2 percent annually on the amount of total capital invested as a fee for managing the plantation. Total capital invested by Cogent Partners would indlude the cumulative total of the initial investment plus the yearly operational expenses Typically when trees were harvested and the teak logs were sold, a timber broker was utilized. The broker's function was to advertise the wood for sale and facilitate the be actual sale. For this service, Matt estimated a 3 percent commission based on gross timber sales revenue. Teak brokers also conducted transactions in U.S. dollars. Matt estimated initial capital requirements of around $8.5 million for start-up of the plantation as shown in Exhibit 8. The initial investment costs included all fixed required such as office and warehouse, tools and equipment, fencing, roads, wells and pumps, irrigation, drainage systems, land and land preparation, and the costs of initial tree planting. The total initial investment cost would be depreciated straight- line over seven years. No land would be purchased; rather the land would be leased and lease payments would be included in the operational expenses. To be on the safe side, Matt included amounts for "unexpected" costs in his totals. assets Exhibit 8: Initial Investment in 2008 U.S. Dollars Based on a 1,000 Hectare Plantation Cost per Hectare Quantity Total Cost General Warehouse and Office 50,000 1 50,000 Tools and Equipment 25,000 25,000 Office Equipment 25,000 25,000 1 Road 8,000 44 352,000 Fence 0.8 15,000 12,000 Irrigation, Fertigation, Computing 2,200 1,000 2,200,000 Welling 1,000 300,000 300 Tractors and Equipment 35,000 6 210,000 Communication Radio 600 4 2,400 Secondary Drainage System 240 240,000 1,000 Infrastructure of Pumping Station 100 1,000 100,000 Sub Total 3,516,400 Unexpected 351,640 10% Total General 3,868,040 Land preparation Land Clearing 350 1,000 350,000 Land Sub-soiling 130 1,000 130,000 90 Plowing 90,000 1,000 80 1,000 Disking 80,000 Sub Total 650,000 Unexpected 10% 65,000 Total Land Preparation 715,000 Turn-Key Planting 3,307,972 3.308 1,000 Unexpected Total Planting 10% 330,797 3,638,769 250 250,000 Initiation Costs 1,000 Total Investments 8,471,809 Source: Cogent Partners Matt's recent reading included research articles by both academics and practitio- ners that suggested to the U.S. equity market risk premium to more fully reflect the various political risks associated with investment in less-developed nations such as Honduras. Matt found that Aswath Damodaran, an NYU finance professor, estimated that the an incremental, country-specific, equity risk premium be added Exhibit 10: Market Data U.S. Risk-Free Rate (10-year Treasury bonds) 2.9% Market Risk Premium: Ibbotson (1926-2008) Geometric Mean 4.9% Arithmetic Mean 6.5% Dimson (1900-2007) Geometric Mean 4.5% Arithmetic Mean 6.5% Country Equity Risk Premium: Damodaran Above U.S. Mean 8.25% (Honduras) Sources: 1. U.S. Federal Reserve (January 2009): http:/federal reserve.gov/econresdata/ default.htm 2. Ibbotson (2008) 3. Dimson (2008) 4. Damodaran (2008) Upon returning to work following the 2009 New Year's holiday, Matt had been gathering additional information and preparing his analysis for the upcoming April 2009 meeting of Cogent Partners. With one month left before the meeting, he needed to pull together his analyses and prepare his recommendation. Complicating his analy sis was the fact that this decision was being made in the midst of a global economic and financial system meltdown that rivaled the Great Depression. Housing prices, which had begun to decline in 2007, were continuing to plunge and Matt wondered how this might affect the long-term demand and prices of teak. The U.S. stock market which had hit a new high in October 2007, had declined throughout 2008 and then plummeted in the last quarter, declining 40 percent by year-end 2008. Although the extremely bad economic conditions were likely to affect teak demand and teak prices n the near-term, Matt was uncertain about the longer term consequences, since the trees would continue to grow regardless of the economic environment. Mitigating his concerns somewhat was the fact that the cash flows from this investment would not be realized for another ten years, at which time it was likely that the economy would have recovered. Because Matt had to decide whether the investment would incr the wealth of the Cogent Partners' investors, he realized that he would need to do a lot of work on sensitivity and scenario analysis, as the many risks associated with the investment were high. An Investment Analysis of Honduran Teak Plantations Lisa Majure, Northern Arizona University Kathryn Savage, Northern Arizona University Matthew Haertzen, Northern Arizona University Alex Finkral, The Forestland Group n March of 2009, Matthew Haertzen, a timber portfolio manager for Cogent Part- ners, was in the midst of his evaluation of an intriguing investment proposal from .Beyond Forestry, a Honduran company that managed teak plantations in Hon- duras. Beyond Forestry employed a unique accelerated teak growth model that used advanced-stage cloned planting stock and intensive forest management in a tropical climate well-suited for the growth of teak. This accelerated growth model allowed for harvesting of teak timber in as few as seven years, compared to 20-30 years for tradi- tional commercial plantations. Currently, Beyond Forestry operates five trial teak plan- tations in Honduras, owned by Honduran business professionals. The company was seeking investors to provide capital to initiate and run a sixth teak plantation. It con- tacted Cogent Partners, the fund managers for Cambium Global Timberland (Ticker: TREE), a UK listed timber investment fund, to see if they would be interested. As portfolio manager, Matt needed to analyze this opportunity from a financial perspective. While he recognized the economic potential of the new growth model, he was also aware of the non-economic factors that might increase the risk of this invest- ment, and the need to factor those into his analysis. The quarterly meeting of Cogent Partners would be held in April 2009, and he needed to determine if the proposed investment was a value-added addition to the Cogent Partners' portfolio. Matt was a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) and an expert in timber investment Prior to working for Cogent Partners, he was the Chief Investment Officer, responsible for the management of both $1.2 billion in financial assets of the Idaho Endowment Investment Board and the $2 billion Idaho real asset portfolio, comprised 90 percent of timberland. His educational background included a BA in economics and an MBA in finance and strategic management TRIP TO HONDURAS Matt was fascinated with the proposal from Beyond Forestry because it claimed that the company's plantations could allow for a very short harvest cycle relative to norms in the teak industry. He knew that natural teak forests generally used a 70-80 year ASso ciation,n harvest cycle, whereas managed teak plantations typically harvested in a 20-30 year cycle. Since Beyond Forestry was claiming to harvest the teak in as few as seven years, Matt initially was quite skeptical of the investment proposal. Controversy had been generated in several countries (primarily in Costa Rica, India, and Mexico) by the pro- motion of teak plantation investment schemes. These schemes used false growth and harvest yield projections, unrealistic pricing scenarios, and dubious fund management strategies to attract investors. "The long time horizons and broad range of price predic- tions associated with teak plantation investment provided opportunities for dishonest entrepreneurs to exaggerate figures and deceive even moderately wary investors." (Pan- dey and Brown, 2006). Additionally, since Beyond Forestry was a start-up company, no financial history of its operations was available for Matt to analyze. Due to these concerns about the potential investment, Matt decided that it would be necessary to visit the existing Honduran plantations to verify the growth and yield data that were presented in Beyond Forestry's investment proposal. Also, due to the lack of financial data for Beyond Forestry, Matt would need to meet with trial plan- tation managers to estimate all of the costs of start-up and operations. In addition to planning the trip, Matt enlisted the help of his colleague, Alex Finkral, a forestry professor, to assist in the assessment of the teak tree growth rates at Beyond Forestry's plantations Matt and Alex visited Honduras in early December 2008. After two days of inten- sive, on-the-ground review of three of Beyond Forestry's plantations, they were able to confirm the rapid growth rates reported in the information that was provided by Beyond Forestry. As part of their investigation, Matt and Alex walked fields to observe irrigation, tree spacing, and general management practices. In addition, the two men marked off sampling plots and took independent measurements to verify the reported growth data. As Matt spoke with his Honduran contacts he learned that the rapid growth of Beyond Forestry's plantations was due to many factors, one of which was the use of cloned seedlings. The growth of Beyond Forestry's seedlings began in the laboratories of Galiltec, a company with demonstrated expertise and experience in developing tissue culture plants for commercial food growing applications. Galiltec's seedlings were the genetic progeny of twenty-five mature Honduran teak trees. In a six-month process, seedlings were cloned in tissue culture, raised in individual contain ers in greenhouses, and outplanted to the field. Beyond Forestry's growth results were also due to the intensive management of its plantations using appropriate irrigation systems, fertilizers, fungicides, pruning, and thinning. Other existing teak plantations typically did not employ modern silvicultural (intensive plantation management) techniques. At the time of his trip, Beyond Forestry had five trial plantations with trees ranging in age from eight to forty-four months Upon their return from Honduras, Matt and Alex performed additional calcula- tions to verify growth rates and net volume projections, and then Matt focused on learning as much as he could about global timber markets in general, the country of Honduras, and the teak wood market specifically Figure 1: Efficient Frontier for Multi-Asset "Traditional" Portfolio 9.5 PORTFOLIO A WITH TIMBER 8.5 PORTFOLIO 7.5 6.5 5.5 4.5 10 20 25 STANDARD DEVIATION % Source: The Campbell Group Reproduced with permission. 3. Awell-diversified timber portfolio provided a consistent yield to meet expenses or provide for beneficiary payments, and timber portfolios could be tailored to deliver targeted income levels based on investor needs. The NCREIF Tim- ber Index averaged nearly a 6 percent income yield since inception (NCREIF, 2008) 4. Historically, teak prices had increased at a nominal rate of 8.3 percent per year over the past thirty years. The basis for the sharp increase was due to rapidly declining supply, particularly of native teak, and rising demand. (Pad manabha, 2006). 5. Forest managers had the option not to harvest in adverse economic condi- tions; rather they could choose to let the trees continue their biological growth and harvest them when economic conditions improved. Teak Markets and Products Although globalization had a profound effect on timber markets, particularly in higher- end hardwood products (such as teak, mahogany, and rosewood), the vast majority of timber markets were still regionally focused and local market specific. This was due primarily to the high cost of transporting logs teak, had good potential for high-end export due to their use in finished products Teak was a tropical tree whose lumber was desired primarily for its appearance and duability. Teak hardwood was used to produce high quality furniture, molding, and looring for the home, as well as trim for yachts, and other applications that benefited from teak's decay resistant qualities. Teak was native to Southeast Asia but was increas- ingly grown commercially throughout many tropical regions. Indonesia and Myanmar the est. Still, hardwoods, like ANNUAL RETURN were the largest producers and exporters of teak. Teak had been planted successfully beyond its native range for more than 100 years and was commonly found in com- mercial plantations in Latin American countries, growing in relatively short rotation (20-30 years). Historically, the largest manufacturers of teak products were found in Indonesia, China, Thailand, and India. Honduran Teak: Economic Value and Wood Quality In general, the sales price charged for teak logs was based on size and form. Teak grown in natural forests commanded higher prices than teak grown in plantations. Data for plantation grown teak logs was available, but limited. Beyond that, larger straight logs without branch wounds (knots) were more valuable than smaller, less straight logs (Keogh, 2008). Larger logs contained a higher percentage of heartwood volume (desirable for its appearance and decay resistant properties) proportional to total log volume than small diameter logs (Percz, Cordero, and Kanninen, 2003). Matt knew that there was no standard grading system for teak and that the variance in price was enormous, in part depending on the amount of heartwood in the tree. An old growth 100-year-old tree could have a price more than six times that of a plantation raised tree, based primarily on the heartwood formation in the very mature trees. For the proposed investment, a specific concern stemmed from the effect of the proposed short harvest cycle on the market price of the teak that would be produced. The accelerated growth techniques used by Beyond Forestry resulted in growth so fast that it was hard to predict the amount of heartwood in the tree Several studies had investigated the effect of intensive plantation practices such as rapid growth, and silvicultural thinning on teak wood quality and stem form (Bhat, 2000a; Bhat, 2000b; Perez and Kanninen, 2005). It appeared that there was no con- dusive evidence that wood quality was affected significantly by plantation practices similar to those of Beyond Forestry. Faster growth and short rotations appeared to have little effect on the strength and specific gravity of teak wood (Bhat, 2000b). In 2006, Beyond Forestry commissioned a study of the workability properties of the teak logs from the first plantation thinnings (Fundacion Cuprofor, 2006). Consistent with other research, the study found that the wood from the small logs was suitable for the manufacture of a wide range of products. Additionally, the characteristics of Beyond Forestry's rapidly grown teak were within the range of "normal" plantation teak Available price data for teak logs grown in Central and South American plantations suggested a "normal" range between U.S. $200/m3 and $300/m3 for small diameter logs, with prices as high as U.S. $500/m3 on record (DeCamino et al., 2002; ITTO, 2006-2007; Keogh, 2008). These small diameters (approximately 15-20 centimeters) had been achieved in Beyond Forestry plantations after three to four years of growth. GLOBAL SUPPLY AND DEMand FOR TEAK Given the sensitivity of the investment to teak pricing, a deeper analysis of the teak market was needed. It quickly became clear that despite them both being called teak, there really were two distinct products in the marketplace. The first was native teak which was often harvested at ages ranging from 80-100 years. The second was planta- tion teak which was harvested at much younger ages (20-25 years in most cases). Native Teak Native (or natural) teak forests existed in only a small number of countries: India, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, Myanmar, and Thailand. Teak was also naturalized in Indonesia, where it was introduced several hundred years ago (Pandey and Brown 2000). During the last twenty years most supplies of teak from natural forests had dwindled. In general, land available for timber production was in a state of decline. Working forests were removed from production as land was sold for alternative uses. In some regions, environmental conservation efforts increasingly restricted the harvest of native teak forests, particularly on publicly owned lands. Significant restrictions had been instituted in several countries. Thailand, India, and Lao People's Democratic Republic banned the harvesting of natural teak forests. Other countries, Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Ghana had all banned teak wood exports. As teak resources declined, the product's value increased Research by Padmanabha (2006) and Gyi and Tint (1998) reported an evaluation of natural teak forests as follows: 1. India (8.9 million hectares): Teak harvest from India's forests was banned in 1997. After that time, fully 100 percent of teak logs used in India were imported (approximately 2.5 million m3). African countries have supplied the majority of Indian teak logs over the past fifteen years, but diminishing supply has driven India to import young teak from Latin America 2. Thailand (2.5 million hectares): All teak harvest was banned in Thailand in 1989 3. Myanmar (16.5 million hectares): Myanmar was the only remaining country in the world supplying native teak. There was clear evidence that the native forests still being harvested were not being done so in a sustainable fashion Significant illegal harvest also continued in Myanmar. 4. Laos (16,000 hectares): The native forests in Laos were too small to provide meaningful levels of teak production. These significant harvesting restrictions had led to sharp increases in prices for natural teak, leading to increased substitution of plantation teak. In addition, the lack of sustainably managed native forests had led many socially responsible buyers to elim- nate their purchases of native teak even where supply was available Research on native teak led Matt to believe that the decline in available product, coupled with the growing global focus on environmentally sustainable wood sources, would lead to increased adoption of plantation teak on a global basis. Additionally native teak was used for high-end products that would not compete directly with the more conventional uses of plantation teak including patio furniture, decking, and other exterior uses where teak's decay resistant qualities were so critical. Plantation Teak The growth and other tropical hardwood, due to its having been grown on a commercial scale for more than 150 years in over fifty different tropical countries. According to Pandey and Brown (2000), 75 percent of current teak plantations were in India and Indonesia. Determining future teak supply from these plantations was difficult due to uncertainty as to specific growth rates, and site quality. However in 1999, Ball, Pandey, and Hirai used a probability model with several specific adjustments to develop estimates. Using lopment teak in plantations was better understood any their estimate of output of 29.6 million m in 2050 and converting that to sawn wood with a 60 percent utilization rate, plantations would meet less than 20 percent of pro jected demand for teak consumption (Ball, Pandey, and Hirai, 1999). The severe supply/demand imbalance resulted in high growth rates in teak prices that were supported by other research reports. Padmanabha (2006), one of the leading researchers on teak, focused on the global teak market, and provided evidence of price increases of greater than 10 percent per year between 1990 and 2000. Figure 2, a chart from his research, revealed historical price increases for all grades of teak. Although the actual prices differed depending on the grade of teak, all grades experienced similar relative price increases. The prices in the figure were for top grade native Myanmar teak, which traded at a significant premium over plantation teak Figure 2: Price and Supply Tre nds of SG-1 Teak logs (Myanmar) Price increases are greater than 10 percent per annum compounded 1500 1500 1200 1200 Price (SUS/m) 900 900 SUS/m m' per annum Supply (m) 600 600 300 300 YEAR Source: Padmanabha (2006) In Matt's opinion, historical price patterns and the predicted decline in the avail ability of sustainable teak made it likely that teak prices would remain strong for the foreseeable future RISK FACTORS In addition to information on price and demand for teak, Matt knew that analysis of the proposed investment required consideration of risk factors particular to an inter national investment in timber. 1999/2000 66966 96/L661 L6/9661 1995/96 56h661 1993/94 E6/7661 26/1661 16/0661 Exhibit 1: Honduras Inflation Year Inflation Rate 2000 14.00% 2001 11.00% 2002 9.70% 2003 7.70% 2004 7.70% 2005 7.00% 2006 8.80% 2007 5.70% 2008 6.90% 9-Year Average 8.72% Source: http://www.indexmundi.com/honduras/ inflation_rate_(consumer_prices).html For Matt, the increasing role of the military added an area of concern-the trade and financial freedom that currently characterized Honduras could change in future years. While it seemed unlikely at present, a government run by the military in Hon- duras could drastically reduce Cambium's ability to realize the potential of its timber investment. Protection of property rights was not strong in Honduras, and political change could weaken the current protection. The firm's exposure was moderated some- what by the fact that it would be leasing rather than purchasing land, but its ability to harvest and sell the timber in ten years' time could possibly be adversely affected by an influential and hostile military regime. A recent insurance industry publication deal- ing with expropriation risk in Latin America cited expropriation claims in Argentina and Ecuador and recommended that investors: "carefully evaluate how threats might evolve over the next few years, rather than focus on conditions today" (Ceniceros 2006, p. 14). Matt had discussed insurance coverage for expropriation with Cambium management in the past, with respect to a different investment opportunity, and knew that they were not willing to reduce their risk by purchasing this type of insurance Environmental Risks Honduran forests were subject to a variety of natural disturbances however, in the last few decades human activities represented the single most significant threat to forests (See Exhibit 3 for a summary of timber specific risks.) Between 1990 and 2005, Hon- duras lost approximately 2.7 million hectares of forest cover to logging and land use conversion, an average annual rate of deforestation of 2.7 percent (mongabay.com). Plantation forests, particularly those that were established on abandoned agricultural land, helped to offset this loss. Exhibit 3. Timber Specific Ris ks Mitigation Risk Site Selection Fire Ongoing Maintenance (fuels reduction) On Site Monitoring Site Selection Wind Tree Age Site Selection Proper Drainage Floods Active Management Aggressive Containment Insects/Disease Site Selection Timber Theft On Site Monitoring Evaluation of Local Markets Pricing Long-Term Supply Agreements Expertise in Physical Commodity Trading Natural disturbances that affected forests in Honduras included hurricanes (and and associated flooding) and in mountain ous areas, landslides. The destructive winds extraordinary levels of precipitation from a hurricane posed significant threats to forest plantations. The proposed site of the Beyond Forestry plantation was near the city of San Pedro Sula in the country's northwest corner and thirty kilometers inland from the coast. Given its distance from the Caribbean co ast, San Pedro Sula was less vulnerable than the coastal regions to the most devastating effects of hurricanes. Nonetheless, flood- ing could occur inland, and flood probability was a consideration in selecting plantation sites. Landslides also occurred in the more mountainous areas of Honduras, but since the Beyond Forestry site was abandoned farmland, the risk of landslide was minimal. The most important potential insect pest for teak in Honduras was the "teak defo- liator" moth (Hyblaea puera), a defoliating insect that occurred worldwide. Despite the presence of Hyblaea puera in Honduras on other plant species, there were no reports that it had occurred in teak plantations (Nair, 2001). Similarly, there were no reported accounts of economic effects in Honduras due to other insects that invade teak for- ests worldwide. Teak was grown in Panama for more than thirty years without prob- lems from insect infestation (United Nature, 2008). Furthermore, Beyond Forestry's proposed model reduced exposure to insect damage through short rotations. Even in a worst case scenario-full defoliation of a plantation-the timber would likely still be merchantable 33cm logs $303.50 10/1/2007 Costa Rica Costa Rica $275.00 33cm logs 3/16/2007 35+ cm logs 10/1/2007 Costa Rica $320.00 11/16/2007 $335.00 38cm logs Panama 11/16/2007 42+ cm logs $365.00 $319.70 Panama Source: ITTO (International Tropical Timber Organization) (Bi-monthly Reports 2006-2007 various) http://www.itto.int/mis_back_issues/ Exhibit 6: Operational Expenses per 1000 Hectares in 2008 U.S. Dollars Yearly Cost Unit Manager 126,000 Field Managers 210,000 Field Workers 512,400 280,000 Guards Vehicle Expenses 73,000 Fuel & Lubricants 71,000 Equipment Maintenance 75,000 Fertilizers 250,000 Fungicides/Pesticides 65,000 Weed Control 70,000 Water including Energy 300,000 Land Lease 367,500 2,399.900 Total Unexpected Costs at 10% 239.990 Total Annual Cost 2,639,890 Source: Cogent Partners The estimated costs of harvesting the teak, including the costs of felling and transporting the logs, were estimated as shown in Exhibit 7. These costs also would need to be adjusted for Honduran inflation. Harvest costs were incurred whenever plantation thinning was per- formed and during any period when teak was harvested. Thinning was necessary to maintain the health of the remaining trees and to ensure that they had sufficient sunlight and room to grow. Typically 25 percent of the existing trees were removed in the thinning phase, which generally occurred in year three and again in year seven. Since the remaining trees continued to grow, they became more valuable with age due to their increased size and volume Exhibit 7: Expected Harvest Costs in 2008 U.S. Dollars Cost per BF-Lumber Cost per m3-Logs Harvest 0.14 Sawing 0.09 Transportation 0.20 Total Cost 0.45 25.00 Source: Cogent Partners The optimal harvest time would be determined via analysis. Matt initially wanted to evaluate seven-year and ten-year harvest cycles. If the trees were harvested in a seven- year cycle, a thinning of 25 percent of the trees would occur in year three and then the remaining trees would be harvested in years six and seven (due to manpower con straints, one-half of the remaining trees would be harvested in year six and the rest in year seven). However, if the trees were harvested in a ten-year cycle, a second thinning of percent of the trees would occur in year seven, and all remaining trees wou harvested in year ten If the investment was made, Cogent Partners would pay Beyond Forestry 2 percent annually on the amount of total capital invested as a fee for managing the plantation. Total capital invested by Cogent Partners would indlude the cumulative total of the initial investment plus the yearly operational expenses Typically when trees were harvested and the teak logs were sold, a timber broker was utilized. The broker's function was to advertise the wood for sale and facilitate the be actual sale. For this service, Matt estimated a 3 percent commission based on gross timber sales revenue. Teak brokers also conducted transactions in U.S. dollars. Matt estimated initial capital requirements of around $8.5 million for start-up of the plantation as shown in Exhibit 8. The initial investment costs included all fixed required such as office and warehouse, tools and equipment, fencing, roads, wells and pumps, irrigation, drainage systems, land and land preparation, and the costs of initial tree planting. The total initial investment cost would be depreciated straight- line over seven years. No land would be purchased; rather the land would be leased and lease payments would be included in the operational expenses. To be on the safe side, Matt included amounts for "unexpected" costs in his totals. assets Exhibit 8: Initial Investment in 2008 U.S. Dollars Based on a 1,000 Hectare Plantation Cost per Hectare Quantity Total Cost General Warehouse and Office 50,000 1 50,000 Tools and Equipment 25,000 25,000 Office Equipment 25,000 25,000 1 Road 8,000 44 352,000 Fence 0.8 15,000 12,000 Irrigation, Fertigation, Computing 2,200 1,000 2,200,000 Welling 1,000 300,000 300 Tractors and Equipment 35,000 6 210,000 Communication Radio 600 4 2,400 Secondary Drainage System 240 240,000 1,000 Infrastructure of Pumping Station 100 1,000 100,000 Sub Total 3,516,400 Unexpected 351,640 10% Total General 3,868,040 Land preparation Land Clearing 350 1,000 350,000 Land Sub-soiling 130 1,000 130,000 90 Plowing 90,000 1,000 80 1,000 Disking 80,000 Sub Total 650,000 Unexpected 10% 65,000 Total Land Preparation 715,000 Turn-Key Planting 3,307,972 3.308 1,000 Unexpected Total Planting 10% 330,797 3,638,769 250 250,000 Initiation Costs 1,000 Total Investments 8,471,809 Source: Cogent Partners Matt's recent reading included research articles by both academics and practitio- ners that suggested to the U.S. equity market risk premium to more fully reflect the various political risks associated with investment in less-developed nations such as Honduras. Matt found that Aswath Damodaran, an NYU finance professor, estimated that the an incremental, country-specific, equity risk premium be added Exhibit 10: Market Data U.S. Risk-Free Rate (10-year Treasury bonds) 2.9% Market Risk Premium: Ibbotson (1926-2008) Geometric Mean 4.9% Arithmetic Mean 6.5% Dimson (1900-2007) Geometric Mean 4.5% Arithmetic Mean 6.5% Country Equity Risk Premium: Damodaran Above U.S. Mean 8.25% (Honduras) Sources: 1. U.S. Federal Reserve (January 2009): http:/federal reserve.gov/econresdata/ default.htm 2. Ibbotson (2008) 3. Dimson (2008) 4. Damodaran (2008) Upon returning to work following the 2009 New Year's holiday, Matt had been gathering additional information and preparing his analysis for the upcoming April 2009 meeting of Cogent Partners. With one month left before the meeting, he needed to pull together his analyses and prepare his recommendation. Complicating his analy sis was the fact that this decision was being made in the midst of a global economic and financial system meltdown that rivaled the Great Depression. Housing prices, which had begun to decline in 2007, were continuing to plunge and Matt wondered how this might affect the long-term demand and prices of teak. The U.S. stock market which had hit a new high in October 2007, had declined throughout 2008 and then plummeted in the last quarter, declining 40 percent by year-end 2008. Although the extremely bad economic conditions were likely to affect teak demand and teak prices n the near-term, Matt was uncertain about the longer term consequences, since the trees would continue to grow regardless of the economic environment. Mitigating his concerns somewhat was the fact that the cash flows from this investment would not be realized for another ten years, at which time it was likely that the economy would have recovered. Because Matt had to decide whether the investment would incr the wealth of the Cogent Partners' investors, he realized that he would need to do a lot of work on sensitivity and scenario analysis, as the many risks associated with the investment were highStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

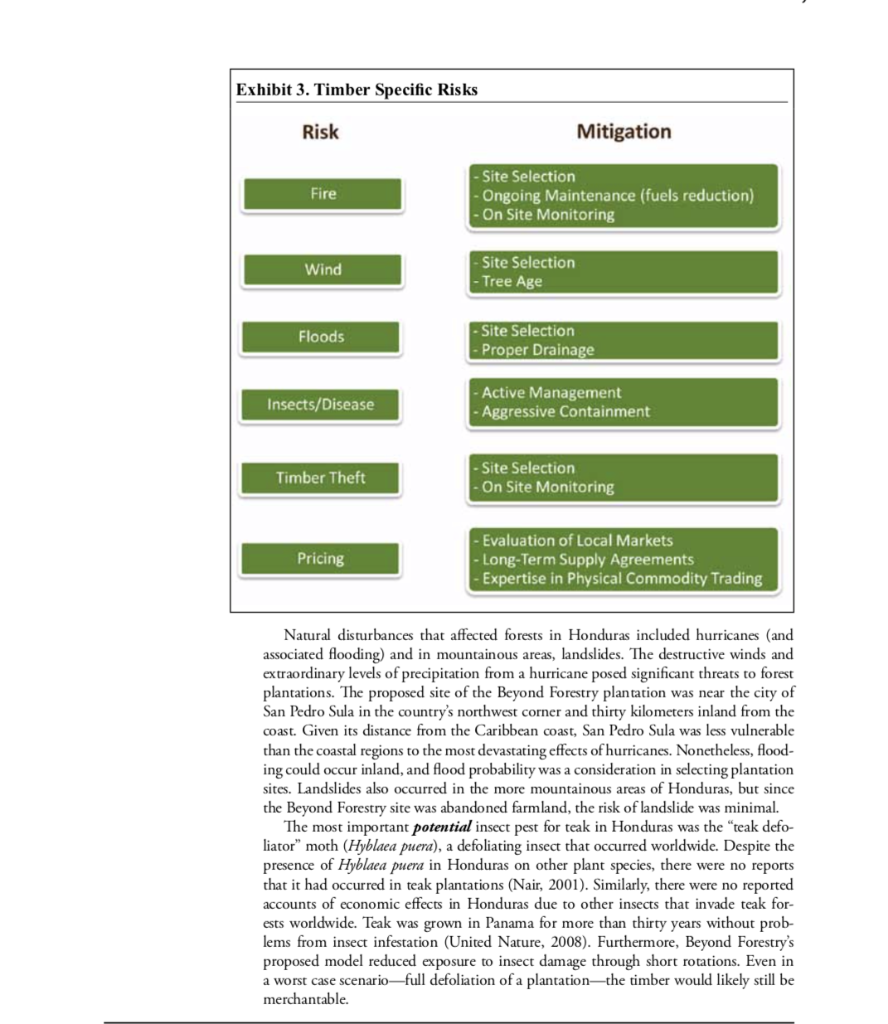

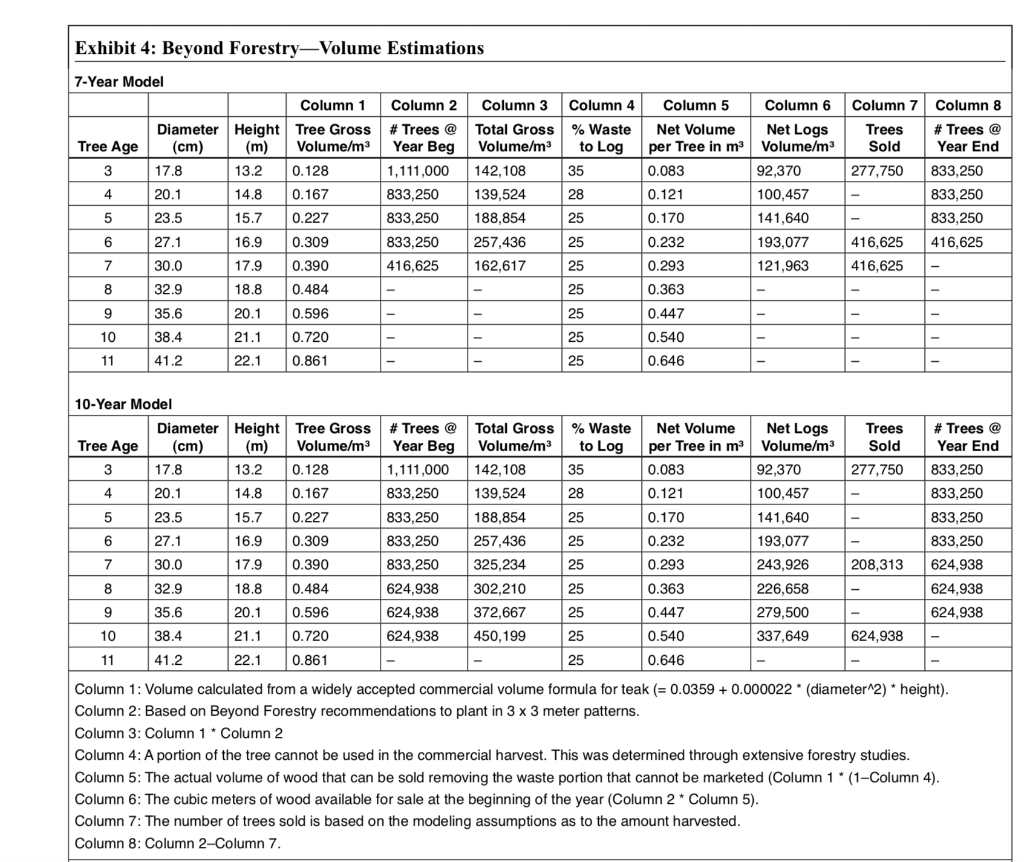

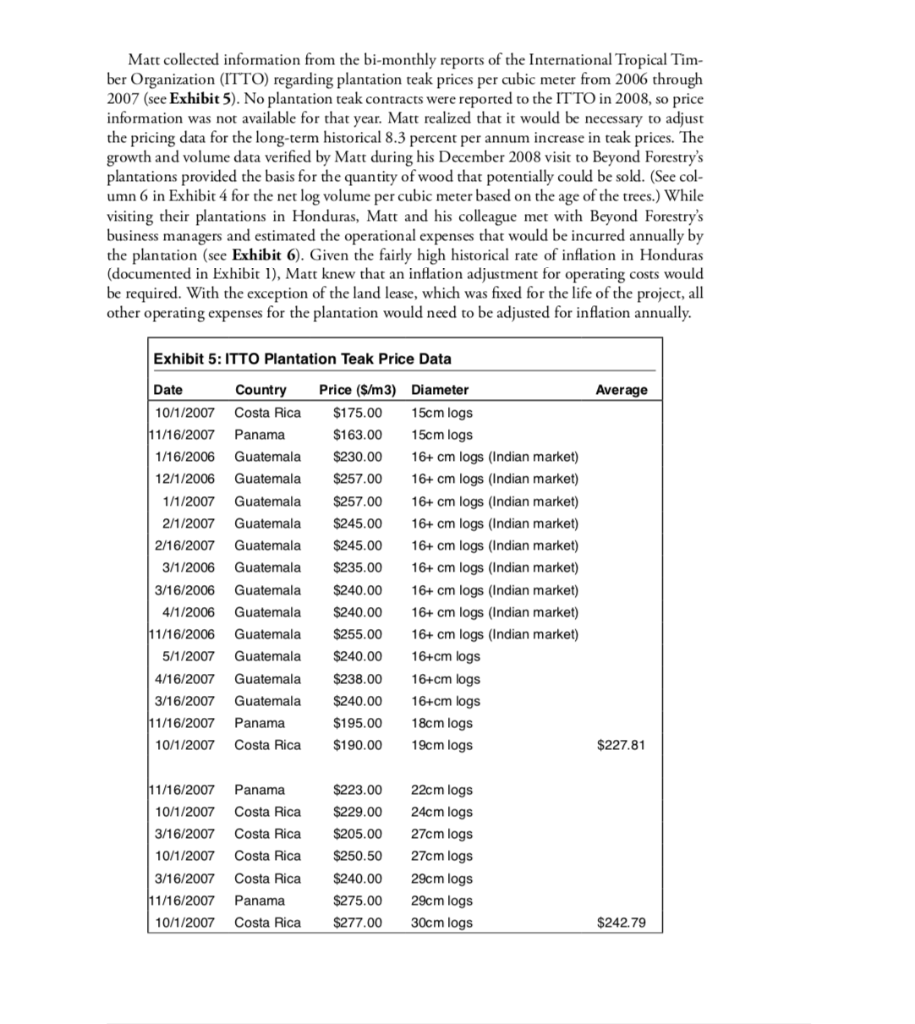

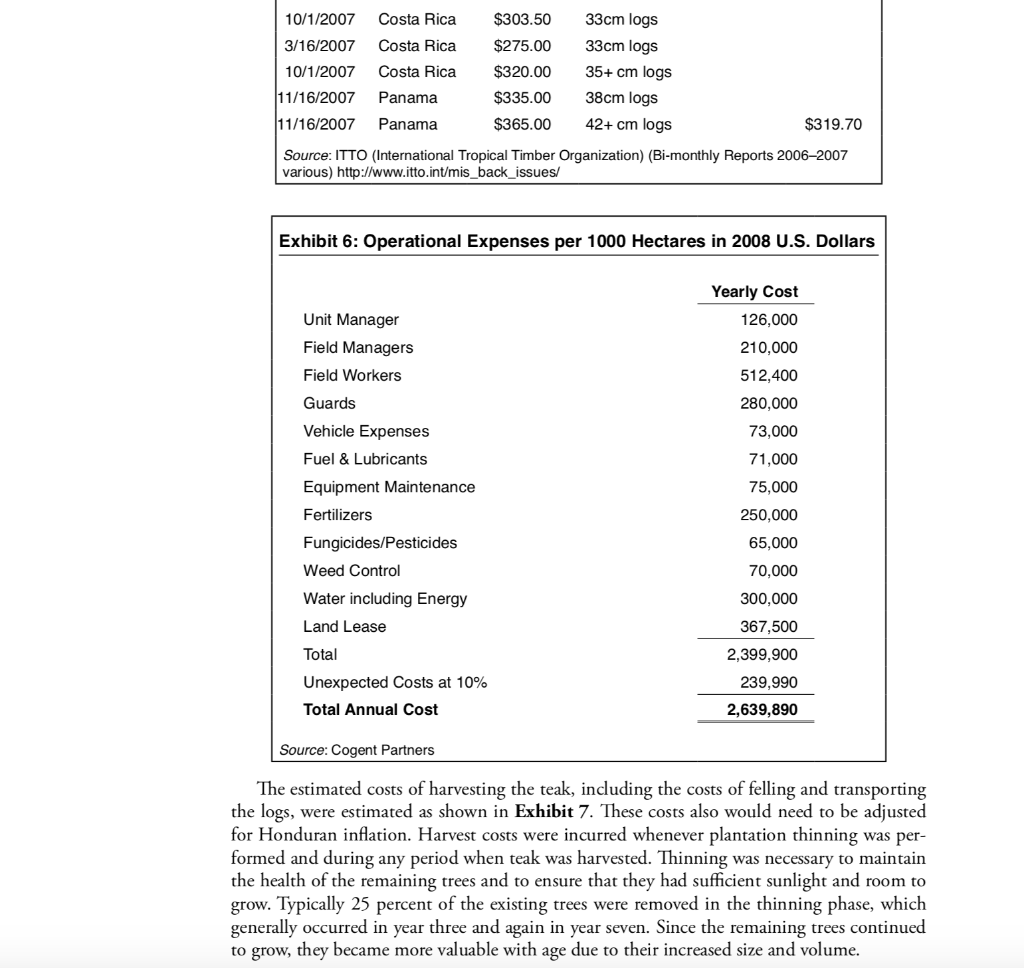

Get Started