Question: Read Read the following article and answer questions 1-3. Google, Inc.: The Risks and Rewards of a Dutch-Auction IPO Introduction On the morning of October

Read

Read the following article and answer questions 1-3.

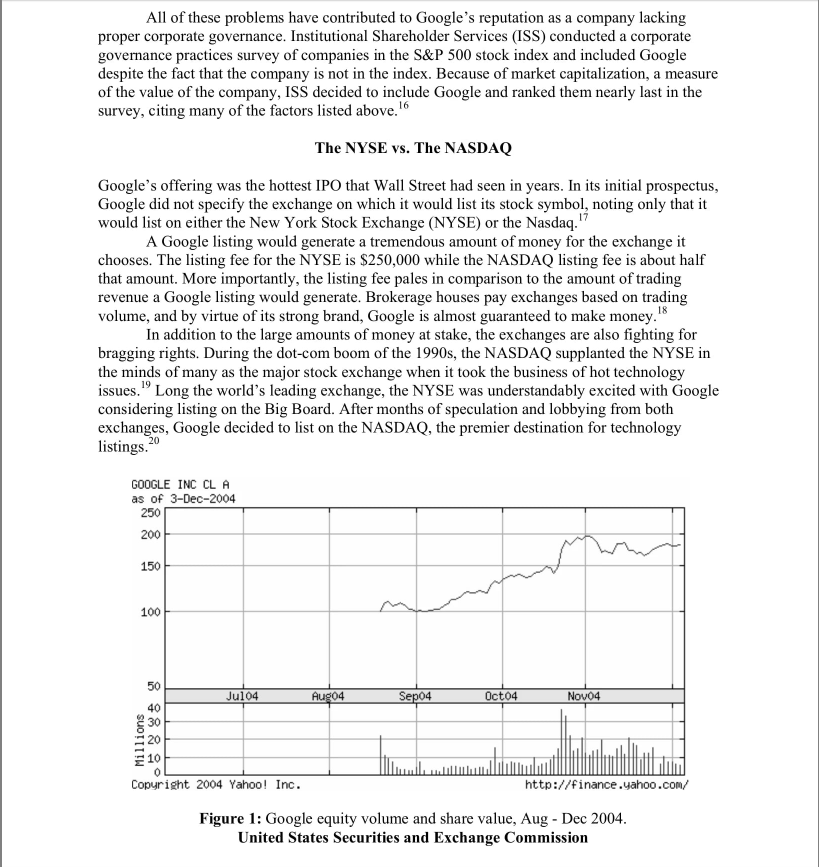

Google, Inc.: The Risks and Rewards of a Dutch-Auction IPO Introduction On the morning of October 22, 2004, Eric Schmidt, CEO of Google, Inc., finished reading the New York Times article under the headline, "A Strong Quarter ... but Skeptics Remain."1 Now, only two months after taking Google public in the largest Internet Initial Public Offering (IPO) in history, 2 Schmidt wondered how he should address the continued scrutiny from Wall Street and the media. Despite Google's loyal customer base of 65 million users a day 3 and its stock trading at $172.54 that morning, Schmidt knew the skepticism would continue as competition heightened and the SEC continued its investigations surrounding the IPO. 4 The Largest Technology IPO in History On August 19, 2004, Schmidt and co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin took Google, Inc. public, selling part of the company in the form of ownership shares. This allowed shareholders to invest in the enterprise while generating capital for the company. This day marked the end of a long journey for Google's IPO. Months prior, the offering was the toast of Wall Street. Google was the first major technology IPO since the dot-com boom-and-bust of the 1990s, but sputtered to the finish line with a host of problems. 5 Google's handling of its IPO process upset many people on Wall Street and beyond due to several missteps. Instead of garnering the company's anticipated share price of $135, trading opened at only $85, almost 40 percent below the projected figure. 6 This reduction lowered Google's potential market capitalization of $36 billion down to $25 billion. Many called this price reduction a failure since the novel "Dutch Auction" that Google used to distribute its shares elevated uncertainties to the point that investors backed away. 7 Since deciding to go public, Google has faced challenges on many fronts and has had trouble handling the growing pains start-up companies face surrounding an IPO. Google has left investors, analysts, and the media with more questions than answers. Many condemn Google's practice of intense secrecy, accusing the company of "playing its cards close to its vest," at the expense of shareholder interests. 8 Accordingly, skeptics have criticized Google's method of addressing Wall Street, as many have had trouble analyzing and forecasting the profitability of this fast-growing company. Further, Google's unorthodox management style and business structure, coupled with increased competition in the search engine sector have left investors concerned about the company's continued viability. Thus, on the eve of the largest Internet IPO ever, many on Wall Street knew as the offering came to a close it was "the beginning of another saga, which is how will the company ... do competitively?" 9 Eric Schmidt now has to answer questions like these, as Google begins its life as a public company. Google, Inc. In 1995, Larry Page and Sergey Brin met at Stanford University as computer science Ph.D. students. By early 1996, the two began a research project to prove a theory that using mathematical algorithms would offer a better way to search for information on the World Wide Web. 10 After years of analyzing computer science, depicting the psychological intricacies of the Internet, and writing mathematical algorithms Page and Brin developed a search engine called BackRub. After taking BackRub to several potential buyers, including Yahoo! founder David Filo, they failed to sell their system. On September 7, 1998, at ages 25 and 24, Page and Brin decided to start their own business with only $1 million in investments. 11 Subletting workspace "googol," which means the number one followed by 100 zeros, was born. 12 Today, Google is the largest search engine in the world and ranks among the five most popular internet sites visited. 13 As mentioned previously, Google has more than 65 million users per day 14 and offers its services in 35 languages. In early 2004, Google handled approximately 80 percent of all search requests on the web. 15 Analysts believe Google's revenue topped $900 million in 2003, with $150 million in net profits. 16 The company is located in Mountain View, California, and has more than 1900 employees worldwide. Google's mission is "to organize the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful [by being] a trustworthy company interested in the public good." 17 Google's success has come almost entirely through word of mouth from satisfied users and the company is one of the fastest growing in history. This success has led to several awards including the Top Ten Best Cybertech from TIME magazine, PC Magazine's Best Internet Innovation and Technical Excellence Award, and Best Search Engine on the Internet from Yahoo! Internet Life. Googling Now a part of Webster's English dictionary, the definition of "google" means, "to search for information on the Internet, esp. using the Google search engine." ,18 Google remains profitable by offering companies its search technology and by selling targeted advertising solutions via its free search engine. Googling is made possible via "server farms" of linux computers that process more than 3,000 search requests per second. Searches are pulled using mathematical alogrithms which conduct simultaneous calculations in a fraction of a second, allowing Google to surpass traditional search engines that pull search requests based on word frequency alone. 19 The company has grown from searching 25 million sites in 1998, to searching more than 8 billion sites in 2004. 20 Google continues to pride itself on offering a free democratic service accessible to and used by the rich and poor, from children on the streets to traders on Wall Street. 21 Dr. Eric E. Schmidt From 1998 through 2001, Larry Page served as CEO of Google, Inc. In 2001, he relinquished his position as CEO to Dr. Eric Schmidt, former CEO and Chairman of Novell, Inc., to become President of Products. Schmidt had also served on Google's Board of Directors since March of 2001. He earned a B.S. in electrical engineering from Princeton University, an M.S. and a Ph.D. in computer science from the University of California-Berkeley. As Corporate Executive Officer and Chief Technology Officer at Sun Microsystems, Inc., Schmidt brought to Google 20 years of experience in software development, management, and marketing expertise. Today, he leads Google, bringing credibility to the former start-up company. Not Your Typical Culture Despite Google's new status as a public company, its corporate culture remains unorthodox and has been criticized in the media, leaving shareholders to wonder whether the company will be able to maintain its unique environment. The Google office dcor includes lava lamps, scooters, rubber exercise balls in the hallways, and a piano in the lobby. The recreation facility has a pool table, foosball table, video game arcade, and onsite masseuse with roller hockey games in the parking lot. There are bins of free food in the kitchens and free meals are cooked by the former chef for the Grateful Dead. Employees, including co-founders Page and Brin, share offices in an effort to increase the flow of information and to keep costs down. 22 Innovation is a key focus for Google; engineers spend 20 percent of their time thinking up new ideas. Day-to-day duties are managed by Schmidt, and decisions are "three way negotiations" with Schmidt, Page and Brin. Investors find Google's controlled chaos unsettling and comment that they "do not sound even remotely like a fiercely competitive world-class company, [but] rather kids playing in a sandbox., 23 One week after going public, Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), criticized Google for "leaving shareholders to place their trust in an unproven senior management team.."24 Page, when asked about what management theories the company applies, summed up the loose corporate hierarchy at Google by stating that they try "to use some theory from different companies, but a lot is seat-of-your-pants stuff." 25 Search Engine Competitors Google's phenomenal success has caught the attention of major players Yahoo! and Microsoft (MSN) who have entered the arena to battle for the heart of the search engine market. All three competitors have unique advantages over the others. Google continues to defend its position as the largest search engine, while these intimidating giants copy its services and integrate increasingly better search capabilities into their hallmark features. 26 Google's most valuable assets are its brand, loyal users, technology, and advertising policy. Google maintains its loyal users by ensuring its searches are editorial products with a clear separation between advertising and information. Unlike competitors such as Yahoo, Google prides itself on disallowing paid inclusion, a practice where advertisers pay to have their website included, and somewhat disguised, as search results. Yahoo's competitive advantages are its technology, execution ability, and large user reach. Since Yahoo is a portal website, providing a range of services such as e-mail, shopping, yellow pages, and finance data, it has acquired valuable information on 141 million registered users that allows personalized results. Yahoo currently has the best execution ability because of Google's management and leadership challenges, while Microsoft may find it difficult to build a search engine from scratch. Nevertheless, Microsoft may be in the best position with its large user reach and enormous research and development (R\&D) budget. The company is planning to integrate web search capabilities by 2006 and has an overall R\&D budget almost twice the combined revenues of Google and Yahoo. The Traditional IPO Process The typical process for a company seeking to go public is to hire an underwriting team of investment banks for their expertise in obtaining the best price for the shares the company wants to sell. The underwriters do this by holding a road show, in which the investment banks present the company's offering to large institutional investors and wealthy individuals, who then tell the underwriters the number of shares they would like to buy and the price they are willing to pay. The underwriters use this information to best approximate demand and determine the appropriate share price. A negative result from the underwriting process is the investment banks' tendency to price the shares lower than their true value, reducing the money generated from the offering. Underwriters will underprice IPOs for a number of reasons. First, they must minimize their risk. Many times, the investment banks agree to buy all the shares from the company, bearing the risk of being unable to resell these shares to the public. If the banks price the offering too high, they will be left holding more shares of the company than they would like or selling many shares at a loss. Thus, to ensure the complete resale of the shares, they underprice the offering. 1 Another reason banks underprice is to serve their investors. The institutional investors and wealthy individuals to whom banks cater are the clients that generate trading fees. Worse than selling the securities at a loss is giving these important investors shares that lose money. Thus, banks have a tendency to underprice so that their best clients will benefit from the shares and will continue to do business with the banks. 2 Since the pricing system investment banks use almost certainly generates a "pop," or large increase in value, on the first day of trading, the customers who can participate in hot IPOs make a tidy profit. Accordingly, investment banks generally dole out shares to their most valued customers, typically institutional investors and wealthy individuals. Google's Atypical Dutch Auction IPO When Google decided to go public, CEO Eric Schmidt reminded potential investors that "Google is a very unusual company in many ways." ,3 The company lived up to this promise when it spurned Wall Street's traditional IPO practice in favor of a "Dutch auction" platform to distribute its shares. Google's Dutch auction is a novel approach to a corporate IPO that is meant to attract and get shares to individual and long-term investors who would hold Google stock instead of the traditional goal of profiting from an IPO "pop." This method also lowers investment banking fees and, in theory, prevents the IPO pop, ensuring that the IPO generates more capital for the company and less profit for outsiders. In Google's Dutch auction, investors register and bid for shares online. 4 The underwriters tally the bids so that the lowest bid price necessary to sell all shares becomes the IPO clearing price. Any bids at or over the clearing price purchase the stock for the clearing price, while those potential investors who bid too little get nothing. Wall Street's Reaction Investment banks became very frustrated with Google's Dutch auction IPO. Instead of garnering the typical 4-7 percent in IPO fees, the Dutch auction limited the underwriters' fees to 3 percent, a reduction of over $100 million. This reduction is justified in a Dutch auction by the fact that there is less of a need for distributing shares since Google's IPO website would accept many of the bids, supplementing the traditional investment banking marketing through road shows. 5 Another requirement Google placed on the lead underwriters, Morgan Stanley and Credit Suisse First Boston (CSFB), and the other underwriters was an unprecedented level of secrecy surrounding the IPO. Google restricted the lead underwriters from disseminating information to the other investment banks on the team. Morgan Stanley and CSFB bankers were upset with the restrictions, and the other banks were even more upset being left in the dark. 6 Eventually, these frustrations caused many on Wall Street to openly proclaim that Google's opening share price would not be as high as the company predicted. 7 They were proven correct when Google opened trading at $85 a share. Investment banks blamed the low price on an inability to predict Google's earnings potential and strength due to company secrecy and its unconventional approach. 8 Nevertheless, when Google stock popped, it looked as if Google's own estimates of its stock value were correct. 9 Critics speculate that Wall Street may have wanted Google to fail in order to deliver value to its clients in the form of a "pop" and to keep its capital raising IPO franchise alive and well. 10 If the Dutch auction system becomes a viable alternative to the traditional IPO process, this may lead to industry-wide cuts in underwriting fees. 11 In addition, this system would eliminate the IPO pop that investment banks like to give to their favored customers. In response to these pressures, critics contend that Wall Street "talked down" the Google offering. 12 The auction method was not the only unusual practice for Google's IPO. Google also chose an odd time to go public. Not only was the summer of 2004 a bad market for technology stocks in general, 13 but the IPO date was set in August, usually a down month for Wall Street. Another unusual feature to the IPO was Google's dual class share system that left certain shares with little effective voting power. Those shares offered to the public have one vote to the 10 votes per share for Google founders Page and Brin. While this structure meets with exchange requirements as long as Google doesn't reduce voting power or issue new stock with wider voting privileges, exchanges generally disapprove of structures in which shareholders are not treated equally. 14 In addition, Google continues to have a strained relationship with Wall Street. Google has stood by its policy that the company would not offer analysts short-term guidance on its business, a common practice for public companies. This lack of information makes it difficult for investors and analysts to gauge the true value of the company. One financial analyst summed up the sentiment of many, saying "we can't adequately answer the question of whether the company's stock is overvalued until we can tell what the company is." "15 investment banking fees and, in theory, prevents the IPO pop, ensuring that the IPO generates more capital for the company and less profit for outsiders. In Google's Dutch auction, investors register and bid for shares online. 4 The underwriters tally the bids so that the lowest bid price necessary to sell all shares becomes the IPO clearing price. Any bids at or over the clearing price purchase the stock for the clearing price, while those potential investors who bid too little get nothing. Wall Street's Reaction Investment banks became very frustrated with Google's Dutch auction IPO. Instead of garnering the typical 4-7 percent in IPO fees, the Dutch auction limited the underwriters' fees to 3 percent, a reduction of over $100 million. This reduction is justified in a Dutch auction by the fact that there is less of a need for distributing shares since Google's IPO website would accept many of the bids, supplementing the traditional investment banking marketing through road shows. 5 Another requirement Google placed on the lead underwriters, Morgan Stanley and Credit Suisse First Boston (CSFB), and the other underwriters was an unprecedented level of secrecy surrounding the IPO. Google restricted the lead underwriters from disseminating information to the other investment banks on the team. Morgan Stanley and CSFB bankers were upset with the restrictions, and the other banks were even more upset being left in the dark. 6 Eventually, these frustrations caused many on Wall Street to openly proclaim that Google's opening share price would not be as high as the company predicted. 7 They were proven correct when Google opened trading at $85 a share. Investment banks blamed the low price on an inability to predict Google's earnings potential and strength due to company secrecy and its unconventional approach. 8 Nevertheless, when Google stock popped, it looked as if Google's own estimates of its stock value were correct. 9 Critics speculate that Wall Street may have wanted Google to fail in order to deliver value to its clients in the form of a "pop" and to keep its capital raising IPO franchise alive and well. 10 If the Dutch auction system becomes a viable alternative to the traditional IPO process, this may lead to industry-wide cuts in underwriting fees. 11 In addition, this system would eliminate the IPO pop that investment banks like to give to their favored customers. In response to these pressures, critics contend that Wall Street "talked down" the Google offering. 12 The auction method was not the only unusual practice for Google's IPO. Google also chose an odd time to go public. Not only was the summer of 2004 a bad market for technology stocks in general, 13 but the IPO date was set in August, usually a down month for Wall Street. Another unusual feature to the IPO was Google's dual class share system that left certain shares with little effective voting power. Those shares offered to the public have one vote to the 10 votes per share for Google founders Page and Brin. While this structure meets with exchange requirements as long as Google doesn't reduce voting power or issue new stock with wider voting privileges, exchanges generally disapprove of structures in which shareholders are not treated equally. 14 In addition, Google continues to have a strained relationship with Wall Street. Google has stood by its policy that the company would not offer analysts short-term guidance on its business, a common practice for public companies. This lack of information makes it difficult for investors and analysts to gauge the true value of the company. One financial analyst summed up the sentiment of many, saying "we can't adequately answer the question of whether the company's stock is overvalued until we can tell what the company is." "15 All of these problems have contributed to Google's reputation as a company lacking proper corporate governance. Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) conducted a corporate governance practices survey of companies in the S\&P 500 stock index and included Google despite the fact that the company is not in the index. Because of market capitalization, a measure of the value of the company, ISS decided to include Google and ranked them nearly last in the survey, citing many of the factors listed above. 16 The NYSE vs. The NASDAQ Google's offering was the hottest IPO that Wall Street had seen in years. In its initial prospectus, Google did not specify the exchange on which it would list its stock symbol, noting only that it would list on either the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or the Nasdaq. 1 A Google listing would generate a tremendous amount of money for the exchange it chooses. The listing fee for the NYSE is $250,000 while the NASDAQ listing fee is about half that amount. More importantly, the listing fee pales in comparison to the amount of trading revenue a Google listing would generate. Brokerage houses pay exchanges based on trading volume, and by virtue of its strong brand, Google is almost guaranteed to make money. 18 In addition to the large amounts of money at stake, the exchanges are also fighting for bragging rights. During the dot-com boom of the 1990s, the NASDAQ supplanted the NYSE in the minds of many as the major stock exchange when it took the business of hot technology issues. 19 Long the world's leading exchange, the NYSE was understandably excited with Google considering listing on the Big Board. After months of speculation and lobbying from both exchanges, Google decided to list on the NASDAQ, the premier destination for technology listings. 20 Figure 1: Google equity volume and share value, Aug - Dec 2004. United States Securities and Exchange Commission Congress established the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 1934 to protect investors by ensuring the fairness and integrity of securities markets through mandated disclosure. This disclosure ensures adequate and accurate information which helps the investing public decide whether to invest. Accordingly, Congress has given the SEC authority to promulgate rules and regulations to accomplish this goal. 21 One of these rules to protect investors is the SEC's prohibition against conditioning the market before an IPO. This rule, known as the "quiet period," applies before the public offering, preventing the initiation of a public sales campaign and restricting the ability of companies to comment with the effect of stimulating interest. 22 Google may have violated this rule when its founders, Page and Brin granted an interview to Playboy magazine which was printed in the September 2004 issue of Playboy, during the quiet period. While the IPO proceeded as planned, the SEC continued to investigate Google after the IPO. 23 In addition to the "quiet period" violation investigation, the SEC also found that Google failed to register options to current and former employees, possibly in violation of federal securities laws. 24 The pair of SEC investigations was just another blemish on the face of Google's once lauded IPO. What's Next for Google? Analysts report they expect the search engine market "to grow an average of 38 percent a year over five years, rising from $2.6 billion in 2003 to $13.4 billion in 2008.,25 The search engine business has become increasingly complex, with user requests becoming more challenging and unusual. In an effort to remain competitive and innovative, Google released new additions to its website this year, such as Google Print, Google Scholar, and Google Catalogs, which continue to focus on the company's core search business. The company has recently grown internationally, with more than 50 percent of its users outside the United States, and there has been speculation that international growth will continue. By early December of 2004 , Google's stock price continued to rise and was trading around $180 per share, despite its initial opening price of $85 per share in August (see Figure 1). 26 Google continues to struggle handling the scrutiny from Wall Street and the media, often having "no comment" or giving vague answers as to its business strategy. When Google has made comments in the media, they often come from co-founders Page and Brin, with very few made by CEO Eric Schmidt or Cindy McCaffrey, the Vice President of Corporate Marketing, who is also in charge of corporate communications. When asked what's next, Google responds, "Hard to say. We don't talk much about what lies ahead, because we believe one of our chief competitive advantages is surprise." ,27 Questions 1. How should Eric Schmidt respond to the scrutiny surrounding Google's IPO in order to retain investor and user loyalty, as well as strong financial stability? Which issues should be addressed first? 2. Who are the stakeholders? How should Google address them? 3. How should Google handle future scrutiny from Wall Street (the United States Securities and Exchange Commission, institutional investors, analysts, and others)Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock