Question

READ THE CASE BELOW AND ANS THE QUESTIONS IN ATTACHED PICS HONEY CARE AFRICA (A): A DIFFERENT BUSINESS MODEL As the sun rose over the

READ THE CASE BELOW AND ANS THE QUESTIONS IN ATTACHED PICS

HONEY CARE AFRICA (A): A DIFFERENT BUSINESS MODEL

As the sun rose over the farming fields of central Kenya on March 15, 2003, Farouk Jiwa began a new day at his Nairobi honey processing plant. For almost three years, he had boldly disrupted the traditional approaches to honey production in Kenya by offering an environmental-friendly livelihood to local subsistence farmers. This for-profit business model, centered on modern beekeeping technology and trusted for its service for the Kenyan farmers, had created a new basis of advantage in a mature and contested market. Its triple-bottom-line approach had attracted local support and international acclaim; yet the faster Jiwa's small business grew, the more challenging it was to balance the creation and capture of economic, social, and environmental value across a rapidly expanding portfolio of stakeholder relationships. Jiwa wondered whether, and how, some of the partnerships pivotal to the venture start-up could now be reconfigured to enhance the scalability and replicability of the business model.

AGRICULTURE IN KENYA

Agriculture employed 75 per cent of Kenya 's labor force, contributed 16.3 per cent to the gross domestic product (GDP), and generated two-thirds of foreign exchange earnings . Only eight per cent of Kenya was arable land, and less than one per cent was dedicated to permanent crops mostly the heritage of the large colonial plantations devoted to coffee, tea, cotton, sugar cane, potatoes, tobacco, wheat, peanuts and sesame. Coffee and tea were also Kenya's main export crops. The majority of the households relied on subsistence farming small lots cultivated with corn (the basic local food), manioc, beans, sorghum and fruit. Small-scale farmers accounted for more than three-quarters of total agricultural production and over half of its marketed production.

The largest economy in East Africa, Kenya had a population of 34.7 million, a real growth rate of 5.8 per cent and purchasing power parity (PPP) of US$1,100. Two-thirds (69.6 per cent) of Kenyans lived in rural areas. Half of the population lived below the poverty line. The poorest 10 per cent accounted for two per cent of total household consumption; the wealthiest 10 per cent were responsible for 37.2 per cent of total household consumption. Forty per cent of the labor force, or 4.74 million Kenyans, were unemployed. Life expectancy at birth was 49 years, and the adult literacy rate was 84 per cent. The United Nations Development Programme 's Human Development Index, a scale based on economic and social factors, ranked Kenya 152 out of 177 countries surveyed, compared to Canada in sixth place and the United States in eighth place.

MONEY FOR HONEY

In March 2000, Jiwa founded Honey Care Africa (Honey Care) to purchase honey from small rural farmers and resell it to Kenya's urban consumers. Honey Care was envisioned, from launch, as a socially and environmentally sustainable for-profit operation that would help make rural communities self-sustaining in the long run. Jiwa's vision was a marked counterpoint to many of the existing business models in Kenya's agricultural sector characterized by corruption and inefficiencies that thinned farmers ' margins and delayed reimbursement for their so-called cash crops.

The first existing business model was that of large government-owned parastatals, which grew and distributed agricultural commodities, such as cotton and pyrethrum. Their monopolistic positions often forced farmers to sell their produce at pre-set and often rock-bottom prices. Farmers were typically reimbursed eight to 12 months after the crop had been collected.

The second model was based on cooperative ventures. These ventures produced and marketed commodities such as tea, coffee and milk, on behalf of their members. Corruption, mismanagement and frequent political interference meant that the farmers often waited many months to be paid for their produce. They frequently had to resort to violence to overthrow corrupt and ineffective management teams.

The third approach involved a long sequence of intermediaries. Farmers sold their honey to individual mid- level brokers, who typically lived in or close to the community; these brokers sold the honey to higher level brokers who had connections with larger businesses and wholesalers. Honey changed hands at least three times through the supply chain, and farmers had limited knowledge of, and access to, the end market. Demand was limited to the number of local mid-level brokers each farmer could access. These so-called cash crops were more a money-making opportunity for downstream brokers than a reliable revenue source for farmers' families.

Kenyan-born and -raised Farouk Jiwa was deeply familiar with the rampant exploitation of small Kenyan farmers, and he was eager to experiment with a radically different approach. With a bachelor's degree in environmental biology and a master 's degree in environmental studies, Jiwa envisioned a profitable venture that was simultaneously committed to environmental preservation and human development. The business model he designed pivoted around the needs of the rural subsistence farmer. He recalled how it all started:

It was all about trying to understand the obstacles facing the farmers. Financing was clearly a problem, technology was a problem, market was a problem, government extension service was a problem. So we thought about it for a while, and asked: "How do we solve this problem for the farmer?" We looked at the sector and said, "If I was the average farmer in Kenya today with two acres of land, what would stop me from producing honey?" We then worked out how to best address each of these problems.

In a dramatic shift from the dominant practice of long brokerage chains, the new venture promised a direct, reliable link between rural farmers and urban supermarkets. Honey Care Africa provided farmers with the tools required to harvest honey, purchased the honey from the farmers at guaranteed and fair prices, packaged it in marketable containers, managed the supermarket distribution and marketed the honey to Kenyan urban consumers. This model transferred much of the margin previously taken by intermediaries back to the rural farmer. Honey Care Africa organized reliable collection of the honey, manufactured and helped farmers acquire hives, provided local training and technical support and, as much as possible, paid farmers in cash within 48 hours. The company gradually facilitated individual ownership of the beehives, initially through private loans and company-sponsored plans, then through donor agencies, non- governmental organizations (NGOs) and micro-financing institutions.

By 2003, Honey Care Africa was working with approximately 1,600 Kenyan farmers. Its radical business model was catching on. More and more farmers were eager to take part. Minimal investment was required, and farmers had an opportunity to purchase their own beehives. Honey Care manufactured and delivered the hives, and guaranteed technical support and timely collection and payment. The business model had been successfully meeting farmers' needs, even exceeding them. Many of the subsistence farmers had been able to substantially increase (and often double) their income levels with only five to six extra hours of effort per month. In its first three years, Honey Care had won the full support of local NGOs, international donor agencies and Kenya's governmental authorities. Indeed, the business model had become a template for international development in the agricultural sector, winning prestigious awards for sustainable development.

Recognition fueled growth, and growth brought several significant operating and management challenges. Honey Care was struggling to handle the rapidly growing volume of honey produce collection, quality control and cash flows were all strained. Relationships with key stakeholders were also rapidly evolving.

BACKGROUND

Founding Honey Care Africa

Honey Care Africa had not been Farouk Jiwa 's first engagement with sustainable business development. In October 1999, Jiwa had joined the Aga Khan Development Network and was posted to one of its companies in Kenya, which sourced vegetables from smallholder farmers, then processed and exported the produce to Europe. The company loaned seeds to farmers, offered extension services and guaranteed farmers fair prices and a market for their produce. Jiwa saw how donor funding and micro-financing accelerated production, reduced the company's exposure, mitigated financial risk and helped the Aga Khan Development Network reach and affect more rural subsistence-farming communities.

Jiwa then turned to beekeeping, a sector where he felt that a similar alliance would yield obvious benefits. Conditions in western Kenya were ideal for producing honey and the practice had a long history in the country; however, farmers had few incentives to take on beekeeping. They were underpaid for their produce, and the cash took months to reach them. Honey was produced mostly by men, who used log hives placed on trees. Previous attempts by the Kenyan government and international donors to introduce modern beehives had failed, due mainly to poor training and support for the beekeepers and unreliable or opportunistic market linkages that hindered the commercialization of the produce. Kenyan customers, increasingly disappointed with the declining quality of the local honey, were turning to imported honey, particularly from Tanzania.

Jiwa came across a well-intentioned but struggling small company: Honey Care International. The Nairobi- based firm, launched in 1997, had not been successful in taking its activities to scale. Honey Care International had distributed Langstroth hives to a few farmers but was not able to collect the honey or pay the farmers in a timely manner. The venture had failed to engage the country's development sector, and its attempt at launching a honey brand had been unsuccessful. By the end of 1999, Honey Care International had managed to figure out how to manufacture Langstroth hives locally, using regionally available material, but was struggling with unpaid bills and poorly motivated staff.

The technology made Honey Care International an attractive investment target. Jiwa felt that a reliable local supply of Langstroth hives was the key to developing the beekeeping sector in Kenya: the hives could enable farmers to produce higher quality honey in larger volumes than traditional methods. He knew how to turn the company around both operationally and financially, but he needed like-minded investors and a free hand to make it all happen.

Jiwa teamed up with two Kenyan benefactors and successful businessmen, Yusuf Keshavjee and Husein Bhanji, and in early 2000, they bought out Honey Care International and founded Honey Care Africa. Yusuf Keshavjee's son, Irfan, and Husein Bhanji 's wife, Shella, also became investors, and together, the Keshavjees and the Bhanjis provided the financing, while Jiwa took on the responsibility of building Honey Care Africa and managing its operations. The partners provided the seed capital and gave Jiwa the freedom and flexibility to run with the idea and make it work. Jiwa recalled how the partners let him "really think outside the box and take risks. " This operational independence was the essential factor that had allowed such a unique business model to take hold. Honey Care Director Irfan Keshavjee recalled:

Farouk proved himself. He's got the passion, the intelligence, the whole thing to make it

move. We were extremely supportive and had little operational involvement. Now that

was very big, it allowed Farouk to do what he wanted to do.

Honey Care Africa's Business Model

Jiwa built a for-profit, sustainable venture with a triple-bottom-line philosophy that would create social, environmental and economic value. His primary objective was to work with the farmers and improve their livelihoods. But farmers had developed a chronic mistrust of corporations, large and small. They also distrusted government representatives and cooperatives, which were never there when the farmers needed them most. The farmers only trusted local NGOs, which had built close, trusting relationships with rural communities over many years. Jiwa approached many of these NGOs, but forging relationships with these organizations was not easy since significant stigma and suspicion had been associated with private sector initiatives. On the surface, the new venture's primary objectives were at odds. Honey Care Africa had strong social and environmental principles but it needed a profit to survive. NGOs, on the other hand, were purely charitable organizations, interested in sponsoring projects that would help build community self- sufficiency without asking for anything in return. And giving had its costs.

Growing up in Kenya, Jiwa had seen too many unsustainable projects. They all worked well as long as the funds from international donors kept pouring in, but as soon as funding ended, these projects quickly fell apart. NGOs in East Africa had even been publicly criticized for undertaking projects that delivered short- term relief but did not result in sustainable opportunities for communities. For example, in the early 1990s, several non-governmental agencies funded the installation of 10,000 water pumps in Tanzania, but did not involve local communities in their set-up or operations. Locals were not trained in how to monitor the pumps, nor held accountable for their maintenance in any way. By the mid-late 1990s, 90 per cent of the pumps became inoperable.

Farouk Jiwa persisted. He explained how his business model would, in fact, support long-term self- sufficiency, a goal that was central for many NGOs. He identified the specific challenges that each development organization faced and thought about how the Honey Care business model would satisfy those interests. He commented on the much more compelling case he had to put to the NGOs:

You have problems of implementation of agricultural projects; you have problems with sourcing the right technology and access to training. There are also issues with information dissemination and awareness creation. But by far, the biggest challenge is with ensuring some level of continuity and long-term sustainability after you exit. Honey Care is going to give you the full package. We'll start with the manufacturing of the hives, we 'll go from village to village to do the demonstrations, we 'll train the farmers right, focus on the economically marginalized women and youth, and we 'll give all the farmers a guaranteed market for their produce and establish a prompt payment system. Above all, we'll continue to offer them a market for their produce long after the project has been wound up.

Once the complementarities became explicit, many NGOs recognized that this small for-profit company shared their goals of building long-term self-sufficiency in rural communities. They realized that Honey Care also put social impact first; commercial viability was simply a means to ensure a sustained contribution to local communities. The NGOs bought into the company's commercial model, recognizing that it could provide a guaranteed and continual stream of income for communities after initial international donor funding had been exhausted. Honey Care welcomed the NGOs' endorsements; their deep relationships with rural communities in Kenya were key to alleviating initial mistrust and providing much-needed working capital for the farmers. This alliance was important because farmers did not have spare income to purchase beehives.

Early on, Honey Care 's founders had decided that the company would equip all their suppliers with the more advanced Langstroth hives (Exhibit 1 has a brief description of the technology). Langstroth hives ensured a much higher level of produce quality and were relatively simple to harvest but, they were five times more expensive than traditional hives.

Initially, the business model envisioned farmers taking out regular loans to purchase the Langstroth beehives. But that wasn't possible interest rates were high (21 per cent), and most banks would not approve loans without collateral, which the poor rural farmers did not have. Honey Care devised a buy- back loan plan; the company would lend the hive to farmers and retain a certain percentage of the monthly revenue generated from its operation. But Honey Care 's limited operational capital constrained its reach.

Many NGOs were willing to provide Honey Care with grant funding for the hives, but only if the hives were owned at the community level. Jiwa resisted. He feared that if hives were owned by groups of people, only some would bother to operate them, and if those people became frustrated and unwilling to keep at it, the investment would be wasted. Honey Care insisted that beehives be individually owned; however, the farmers could work as a group on particular activities. They could share the bee suits and the smoker. Eventually a compromise was reached. The NGOs conceded on the need for individual ownership; Honey Care agreed to support and work with existing groups.

Honey Care and the NGOs also disagreed on the basic principle of providing the hives to farmers free of charge. The NGOs were not interested in receiving money in return for the hives, but Farouk Jiwa was sensitive to the implication of giveaways. Free hives could be perceived as a discretionary asset, giving farmers no real incentive to produce honey of the quality desired. Honey Care insisted that a pay-back plan would signal to farmers that honey production was an economically viable activity that they could undertake without external help. Honey Care would retain 25 to 50 per cent of a farmer's monthly income and remit this amount to the NGO until the full cost of the hive had been recovered. This way, hive ownership in itself would become an important economic motivator: once farmers owned their hives, the economic pay-offs of honey production would almost double.

Eventually, the NGOs endorsed this position and agreed to purchase the hives for Honey Care. The firm would lend them to the farmers who could purchase the hives gradually, at their original cost. Honey Care would then place the returned funds into a savings account that could be used by the community for expanding the hive base and/or other development projects.

The Farmers

For the farmers, the partnerships with local NGOs and community-based organizations (CBOs) were an important signal that Honey Care was genuinely committed to Kenya 's rural farming communities. But actions had to follow. As Jiwa explained, Honey Care 's relationship with the farmers was equal, fair and sensible:

I think you just go out there and speak with the farmers very honestly and without being

patronizing. You explain what 's in it for them and you explain what Honey Care intends

on getting out of this. Above all, you listen to what they have to say and take their input seriously.

This was a very different approach from the way farmers had been treated before; government representatives would lecture farmers for two hours straight, giving them little opportunity for feedback or dialogue. Jiwa put away the podium and engaged farmers in a two-way conversation. It took him a while to break the ice, but the farmers quickly warmed up to his open, frank style. Above all, they recognized Honey Care's genuine interest in understanding and meeting their specific needs.

From the outset, Honey Care implemented a money-for-honey plan. They paid farmers fair prices, on the spot, under a detailed and formal contract (see Exhibit 2). No other firm had done anything like this before. Even the Coffee Board of Kenya delayed payments for eight to 12 months. Jiwa still remembers the enthusiasm and positive press this approach generated as they were getting started.

Honey Care's pilot project began, quite literally, with a search through the Nairobi Yellow Pages. Jiwa found out that DANIDA, the Danish International Development Agency, was engaged in a small development project in a semi-arid region of Kenya. He requested the agency's financial assistance to help implement a small-grower beehive feasibility study in this region. Jiwa explained the specifics of the business model and his intention to guarantee on-the-spot payments. DANIDA was intrigued by this idea and agreed to fund a pilot project of 100 beehives. Fortunately, weather conditions were favorable, and a good harvest was quickly ready. Jiwa planned a public celebration of the success and invited many of the development agencies active in Kenya. Only two donors showed up, but fortunately so did the Daily Nation, the largest circulating newspaper in East Africa, which published a full front-page article on the project.

Immediate cash payments were needed and appreciated by the farmers, but Jiwa also knew that sustaining high-quality honey production also required initial training and on-the-ground technical support. Governmental ministries provided some assistance through ad hoc training services, but Jiwa felt that Honey Care should provide more specific support. He initiated formal and informal training schemes that taught farmers the technical peculiarities of honey harvesting using Langstroth hives. The training covered beehive maintenance, pest control, safety and protection (e.g. bee suits), proper harvesting techniques and other activities related to the honey harvesting process.

Honey Care also employed a team of project officers, who were dedicated to a small number of farmers in their neighboring communities. The project officers were aware of the cultural idiosyncrasies of their neighborhoods and were deeply committed to the social development of their communities. Project officers made regular visits to the farmers to see how the honey harvest was progressing. As Rob Nyambaka, Honey Care 's operations director explained, they were available whenever the farmer needed advice on any aspect of the harvesting process:

The Project Officer is the key: they essentially ensure that the farmer produces the honey.

They also play an important role in knowing what is happening on the ground. Because

most of them are from the local community and speak the language and know the culture,

they are able to continuously gather the right information about the status of the projects.

Whatever happens in the field, we, here at head office, will know. This helps us constantly monitor the needs of each particular community. What exactly are their problems? What exactly do they need? Project Officers act as a link between Honey Care and the community. They are the Honey Care presence in the field. Whenever the communities see the Project Officer, they know Honey Care is in the field. This has never happened with other honey buyers. They come this season, disappear for the next six to eight months, come again for a day next season, disappear for the next six to nine months, come again for a day, disappear for another six to eight months. They simply do not have the same close relationships to the farmers as we do.

Project officers worked one-on-one with farmers to maximize their yield and quality. Their dedication and willingness to lend a hand, whatever the problem, was sincerely appreciated by the farmers. Lucas, a Honey Care farmer based 60 kilometers outside of Nairobi commented:

It 's an advantage to have the Project Officer here. He 's the one who coordinates things, he

is always there when we need him and knows how to best ensure we get the highest honey

yield. We need him a lot. . . . He even comes and helps us with other things. Like cleaning

the hive when there are some insects, helping us fight the mice. When we get such problems, it's him who we contact.

The Employees

Honey Care trainers and project officers were carefully selected to embody the can-do spirit of the founders and to share their belief that a market-based approach could make a difference in community development. They were intrinsically motivated to do their very best, and they knew that Honey Care was revolutionizing the beekeeping sector in Kenya. Employees working in the field had close bonds with the local farmers and felt personally accountable for their success. Employees at head office and in the production room also felt they were making a difference, and they often worked late to meet an order.

Jiwa diffused his vision of what Honey Care Africa stood for, one employee at a time. He would often bottle honey shoulder-to-shoulder with his employees, reminding them that packaging was essential for attracting customers. He could also be found spending time in the workshop with the carpenters or loading boxed jars onto trucks. Day after day, everyone developed a clear, deep sense of what the business model was all about. No one wanted to short-change subsistence-farming communities; they had all come from such a community and could envision the difference quality honey production could make for their friends and relatives. The sense of personal duty permeated the entire process, from the production of beehives to the distribution of the honey jars to urban supermarkets. The employees clearly understood the roles they played in the business model and looked after their specific tasks with utmost care. The carpenters assembling the beehives tasted the honey their uncles and grandfathers produced using the hives; they knew that the farmers' ability to produce high-quality honey and generate a substantial source of income depended, at least in part, on their own commitment and craftsmanship.

Jiwa wanted to keep Honey Care employees motivated every step of the way. He had seen first-hand that even the most personally invested field officers working for the Ministry of Agriculture sometimes delivered sub-par performance in rural communities. Jiwa set out to establish clearer linkages between the efforts made by project officers in the field and the quantity and quality of honey produced by the farmers. Honey Care devised an incentive program that gave project officers a bonus on top of their regular salary for every kilogram of honey produced. This bonus was awarded at the end of each year. For the first year of the plan, individual bonuses ranged from five to eight Kenyan shillings (KSh) for each kilogram that the project officers helped the farmers produce (the equivalent of 6.6 to 10.5 cents in U.S. currency. This is a third of a loaf of bread at $0.35 a sixth of a packet of sugar at $0.63, and half of a bottle of Coca Cola at $0.21 ). The incentive plan had an unexpected positive impact on Honey Care's forecasting accuracy. Because project officers monitored local honey production closely, the firm knew in advance how much honey it would collect every month. Thus, Honey Care could ensure sufficient cash in hand, better manage processing capacity, make informed downstream market commitments and plan distribution activities.

MILESTONES IN THE EVOLUTION OF THE BUSINESSS MODEL

Winning Supermarket Shelf Space

The pilot project with DANIDA set the business model in motion. After the first two to three months of operation, Honey Care harvested 200 kilograms of honey. Now it had to find a way to market the produce to urban consumers. Farouk Jiwa recalled the daunting challenge of coming up with a label, putting it on jars filled with honey and then trying to get supermarkets interested in the product. At first, he had to wait three to four hours to see supermarket marketing reps only to convince the supermarkets to take five or six jars on consignment. Once customers developed a taste for the high-quality honey, the stores began calling back for more.

Joining Forces with Africa Now

Africa Now was an attractive partner for Honey Care because it had significant experience with small- grower beekeeping in Somalia and other parts of Kenya. Africa Now was also one of the few NGOs interested in enabling entrepreneurial development in rural Kenya, and it was a vocal champion for fair treatment of small farmers. Rob Hale, Africa Now's country director for Kenya, was keenly aware of the structural flaws in the existing honey supply chain: " The Kenyan honey care sector as it stood was not sustainable for the farmers. As an NGO,

we could help improve their beekeeping skills, but neither we nor the farmers had the business acumen to market the honey. There 's no way the farmers could increase the price locally to improve their margins so this meant that they would have to harvest a much better quality honey to sell in urban areas. But then they would need to package and transport the honey and that's only worth doing when you have sufficient volume. Marketing the honey has always been a problem. "

Honey Care's model was a perfect solution; its approach provided a perfect match for Africa Now 's capabilities. Jiwa still remembers the first encounter between the representatives of the two organizations. Both he and Rob Hale had traveled to the World Bank 's Development Marketplace competition in Washington, DC, in January 2002. They stood next to one another for five days, 12 hours a day, talking about the same thing. They completely understood one another, and by the end of the competition, they could almost predict each other 's words. Jiwa and Hale became good friends. Their strong personal connection and commitment to a shared goal infused all aspects of their partnership. At the strategic level, Farouk Jiwa and Rob Hale maintained a steady and healthy tension. They constantly debated the new opportunities for providing additional services to farmers, and, in the process, collaboratively refined Honey Care's original business model. Jiwa commented:

Rob helps keep us on the straight and narrow. It's good to have somebody out there who

comes from a little more on the social side of the spectrum than you are. Then we come in

a slightly more on the business side of the spectrum and say "Well that's great Rob, that's

wonderful, but can we actually make some money on this. " So the question I ask Rob

every single time is, "What are we going to do when the grant finally runs out?" and the

fundamental question Rob asks me is, "What would you have done if the donors didn't

have the money to start with?"

The convergence of interests between Farouk Jiwa and Rob Hale also filtered down throughout the organization, affecting every aspect of Honey Care's operations. There was a tremendous amount of transparency between the two organizations. Payments to the farmers were always made in the presence of Africa Now. Communication between the two organizations took place across all levels on a day-to-day, week-to-week and month-to-month basis. It quickly became an accepted norm that all major decisions of one organization would affect and involve the other.

The two firms shared operational resources, including personnel, logistical facilities and vehicles. Africa Now already had human resources on the ground in western Kenya and it assisted Honey Care to provide field services in several rural areas. Africa Now also had bases in most of Honey Care 's farming areas, so Honey Care used Africa Now 's facilities to conduct its administrative functions. This arrangement saved Honey Care substantial overhead expenditures when it was getting started. Furthermore, Africa Now's employees working in areas not yet serviced by Honey Care spread the word about the new business model among small-scale producers in western Kenya. Many farmers bought into the model, and Honey Care 's supplier base quickly expanded. The images of Honey Care and Africa Now became inextricably linked in farmers ' minds because the companies endorsed each other and shared personnel and facilities in many communities. In fact, many of the farmers felt they were dealing with a single organization. This increased the loyalty of the farmers to Honey Care.

Supplier Loyalty

Honey Care's entire business model relied implicitly on farmer loyalty. However, Honey Care did not have a monopolistic relationship with the beekeepers because many of the hives were obtained with NGO support; farmers could sell their produce to any broker. Because of the superior quality of the honey produced using Langstroth hives, other brokers were now skimming the harvest by offering KSh10 to KSh20 a kilogram more than Honey Care's KSh100 KSh per kilogram. Those farmers who had taken their hives on the buy-back plan were only receiving 50 to 75 per cent of the Honey Care rate, so selling to the higher bidder was sometimes tempting. Everyone in the field was aware of cases where farmers had taken advantage of the higher margins. These were, after all, small rural communities with incomes barely above subsistence levels, which were often pressed for cash for urgent needs. But overall, the community remained loyal to Honey Care. Lucas, one of the Honey Care farmers, commented on the situation:

There was one member who was not being cooperative and well he was thinking of selling

his honey somewhere else, so we talked about it and now he changed his mind completely.

We disowned him. We told him that we 'll not deal with him. If he thinks of looking for a

market anywhere else, then we won 't deal with him as a community. But we have changed

him, and now he 's all right.

Honey Care lost some farmers to ad hoc and opportunistic competitors, but many of them returned once these competitors vanished. As Jiwa explained, returning farmers developed an even greater appreciation for Honey Care 's consistency and the guaranteed monthly payments that came every collection cycle:

We're always amazed, but farmers almost always come back to us. I guess the one thing

we are doing right is our level of consistency. When we tell farmers we're going to be out

there next Wednesday to collect the honey, we do it. There 's no substitute for the ability to

keep our promises.

Initially, the plan had been to rid Honey Care of opportunistic suppliers by providing the super (the upper portion of the Langstroth hive where the honey was stored) free of charge. The rest of the hive was owned by the farmer, but the super belonged to Honey Care. Project officers collected the filled supers and replaced them with empty ones. Although this practice reduced the chance that farmers would sell to ad hoc competitors, the process was not sustainable. As the farmer base grew, Honey Care realized that the supers were locking up a significant portion of the company 's finances. Supers were distributed throughout the country, and replacing them at each harvest was costly. After carefully considering the pros and cons, Honey Care adapted its business model so that the farmer owned the entire beehive. This decision to earn the trust of the farmers, rather than limit the odds of opportunism, paid off.

UNEXPECTED OPPORTUNITIES

By the middle of 2002, Honey Care had become a well-known local symbol of work ethic with a track record that reflected its dedication to small farming communities. Its reputation attracted World Vision, which was trying to revive productive assets left idle. One of Honey Care's new competitors, located just outside Nairobi, had sold a number of traditional beehives to World Vision. The entrepreneurs had promised to collect the honey intermittently, pay the farmers and market the honey; instead they cashed in the operating budget and left the hives unserviced. The NGO distributed these hives to local farmers, but the entrepreneurs had not even come to meet the farmers who had bought these hives. World Vision asked Honey Care if they could take over and fulfill the promise given to the farmers. They did.

Another unanticipated opportunity accompanied the declining demand for the project officers' extension services. As farmers became more skilled at harvesting the honey, they did not need as much day-to-day support from the project officers. Eventually, their role began changing from demonstrating the harvesting and maintenance techniques to providing advice on how to increase the purity of the honey. Project officers now had more time for new responsibilities.

OPERATING CHALLENGES

In its first years of operation, Honey Care concentrated on fulfilling its social and environmental promises. Strong relationships with international funding agencies and other donors had channeled sufficient funds to sustain and gradually expand the company 's operations. But its quick and resounding success was now posing several challenges.

Beehive Financing Challenges

To expand, Honey Care needed to make significant investments in beehives. Initially, Honey Care had purchased the beehives and loaned them to farmers, who then paid back small monthly sums toward eventual ownership of the hives. Later, several NGOs had paid for some of the beehives, but growth had outpaced the donor funding. Even with the NGOs' help, the investments in the beehives had exceeded Honey Care 's capacity and had become a significant constraint on the company's cash flows.

Relying on donors had constricted Honey Care's potential for growth. NGO funds could enable more farmers to acquire beehives, but they could not fully meet the demand. Furthermore, the NGOs' involvement was only temporary. They would work with a community for three to five years but could not offer a long-term solution to the increasing need for beehive financing. Honey Care was searching for a commercially viable approach that could accommodate both the rapid pace of expansion across Kenya and the longer-term prospects of the farming communities.

Africa Now facilitated a partnership between Honey Care and K-rep Bank, which had introduced new micro-financing opportunities through its Nairobi and Kisumu branches. Better access to beehives fueled explosive growth for Honey Care across western Kenya. As more farmers got access to hives, Honey Care achieved some economies of scale in processing the honey. However, growth brought about new challenges in managing prompt cash payments to the farmers.

Payment Challenges

On-the-spot payments had been pivotal for the farmers, but as the volume of collected honey increased, Honey Care representatives were handling significant amounts of cash. They were at significant risk from highway robbers. As Vip Kumar, Honey Care 's commercial director explained, the company had to find simpler, safer and more effective ways of managing cash payments:

We 've always paid for the honey at the farm gate, but as the numbers increase, there's a

greater and greater risk of carrying cash around. We are now essentially trying to deposit

the funds right into the farmer's account of a local bank. This will reduce cash handling. It

might take a slightly longer time. Perhaps it'll allow a means of savings and allow them to

take on other investments maybe buy more hives or other equipment through leasing mechanisms that we've developed with financial partners. But the village bank network is

still quite small and not widespread. This is a considerable challenge.

A second challenge was the time lag between Honey Care 's payments to farmers and its receipts from supermarkets usually several weeks. As volume increased, Honey Care's cash flows could not cover the entire lag. However, delaying payment to the farmers could jeopardize their hard-earned trust. Vip Kumar had already considered this alternative:

If we're unable to find a way to deal with this then we're going to have to talk to the

farmers honestly and say, "Look, this is a long-term relationship, we've built it over many

years and the money is guaranteed and clearly you'll get the money in three or five days."

But going into the field twice, once to collect the honey and then again to pay the farmer, would be expensive. Honey Care was unsure how to organize the payments.

Collection Challenges

With increasing numbers of farmers joining the program, the initial model of collecting from each individual producer was becoming less feasible. Honey Care was again toying with the idea of establishing collection centers. It was a typical model for Kenyan agriculture; farmers from a particular community would come together at one central location to deliver their produce and receive payment. Collection centers had their downsides, but they would enable more farmers to extract their honey and be paid in the short harvesting season. As Kumar explained, each community would gain but individual farmers would have to bring the honey to the collection centers:

Let 's make it easier for you and for us. We now have sufficient farmers in an area. Let's encourage them to deliver to a central location, a centre which is collectively managed by Honey Care and individual groups and use that as a centre for letting farmers bring the honey to us now. This allows them to harvest in that short cycle that we have the several weeks available in the season. So we want to try and get as many farmers extracted as possible. And the way we do is to have a collection centre available rather than the farmers waiting for us. It certainly means more farmers have access and can get their honey extracted and get paid.

Quality Challenges

Higher volumes also meant greater stocks and longer shelf life. Honey Care had to find ways to maintain stock levels, check the heights of the fill and prevent crystallization. There were also consequences for the bottling process, which now needed to include micro-filtration and improved honey pasteurization processes. Both would require additional investments in technology and human resources.

Partnership Challenges

Many of the NGOs had come on board with Honey Care for short periods of two to three years. Their original partnerships with Honey Care were now coming to an end; their projects were completed, and they were exiting the rural communities. Honey Care had been wise, and fortunate, to attract NGO partners that had maintained a hands-off approach. Operationally, the transition would be easy; however, some of the partners had played a key role in reshaping the initial business model and might continue to do so moving forward. The relationship with Africa Now had been a symbiotic one. Farouk Jiwa anticipated that Africa Now would continue to play a pivotal role for Honey Care, but the parameters of this role were still to be defined. Africa Now could play a pivotal role in setting up the collection centers; they might encourage more farmers to join the company; they might help build operating capacity as bee farming communities grew; they might help with alternative financing mechanisms or they might facilitate other trade linkages.

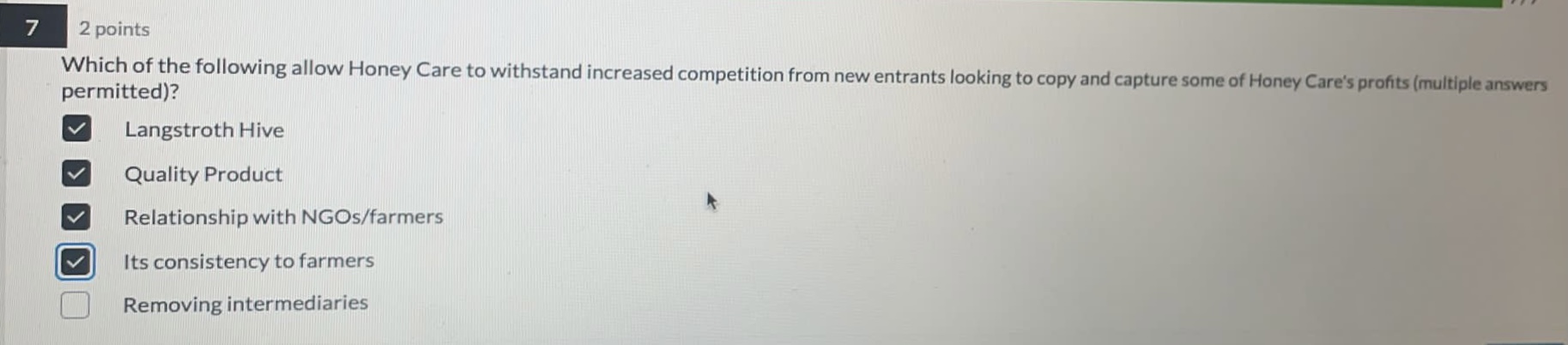

ANS THE QUESTIONS IN ATTACHED PIC ( IGNORE THE MARKED ANS , THEY ARE INCORRECT ) :

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started